Abstract

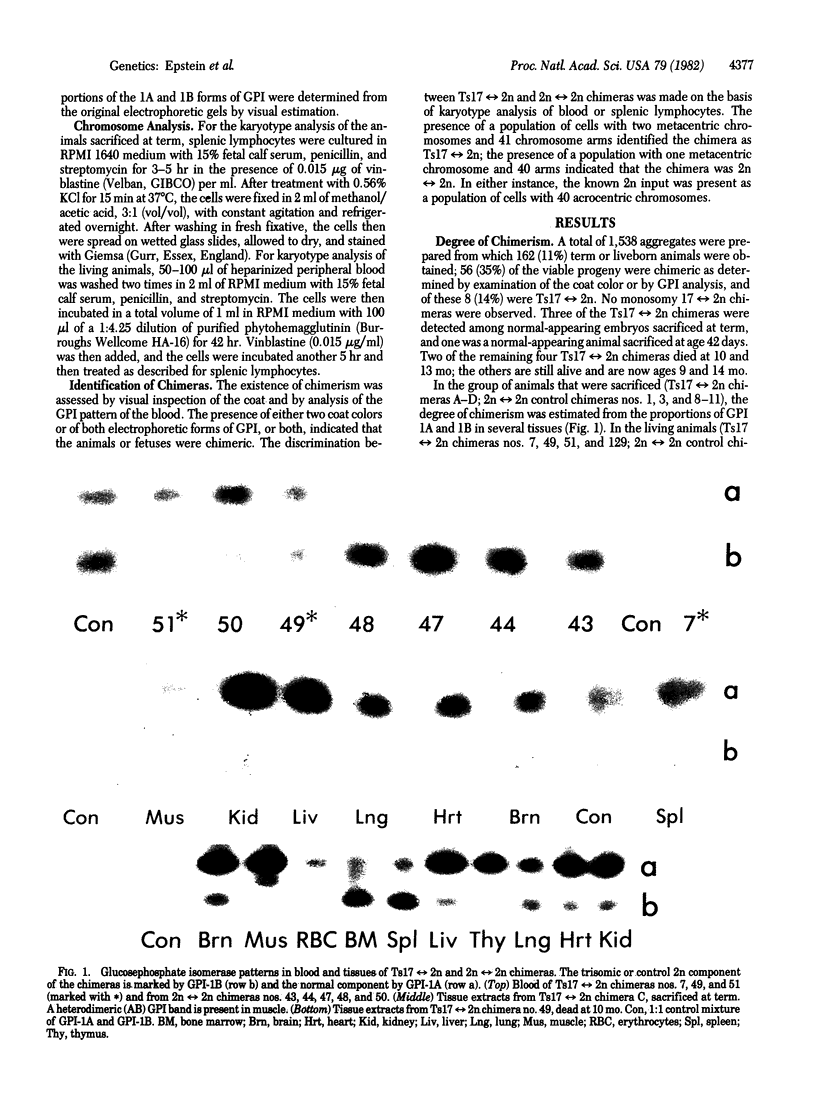

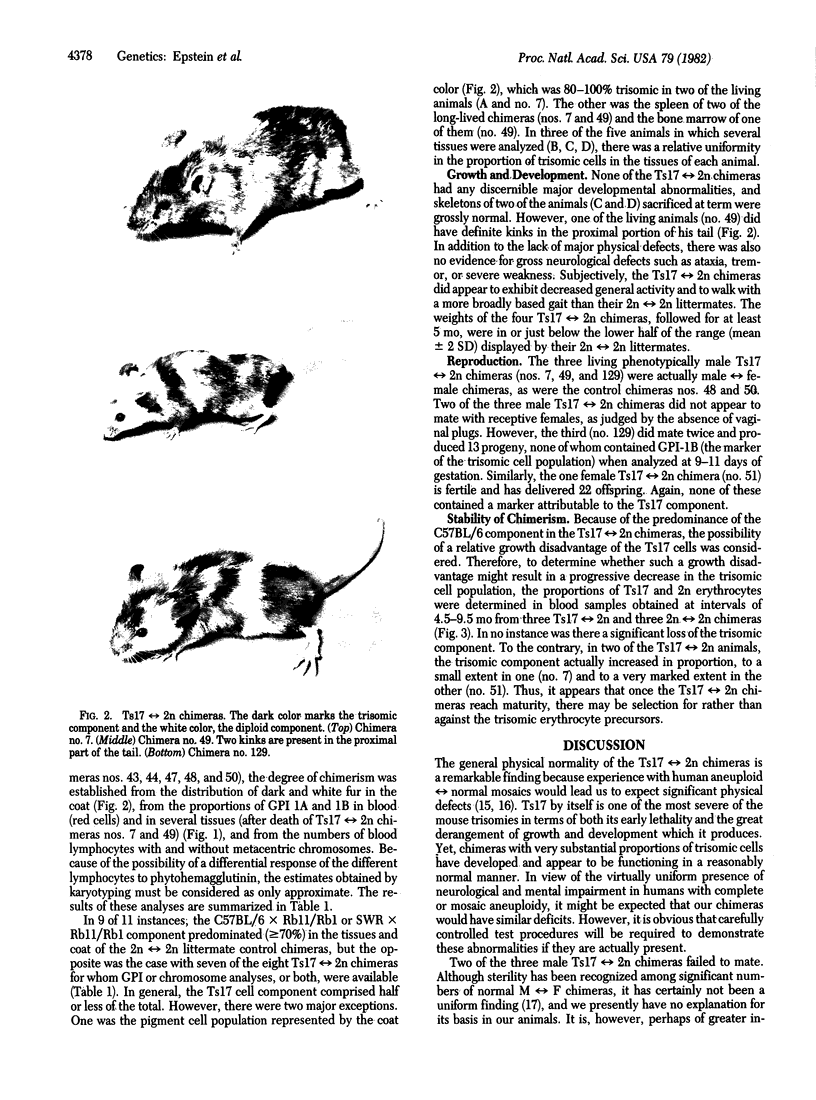

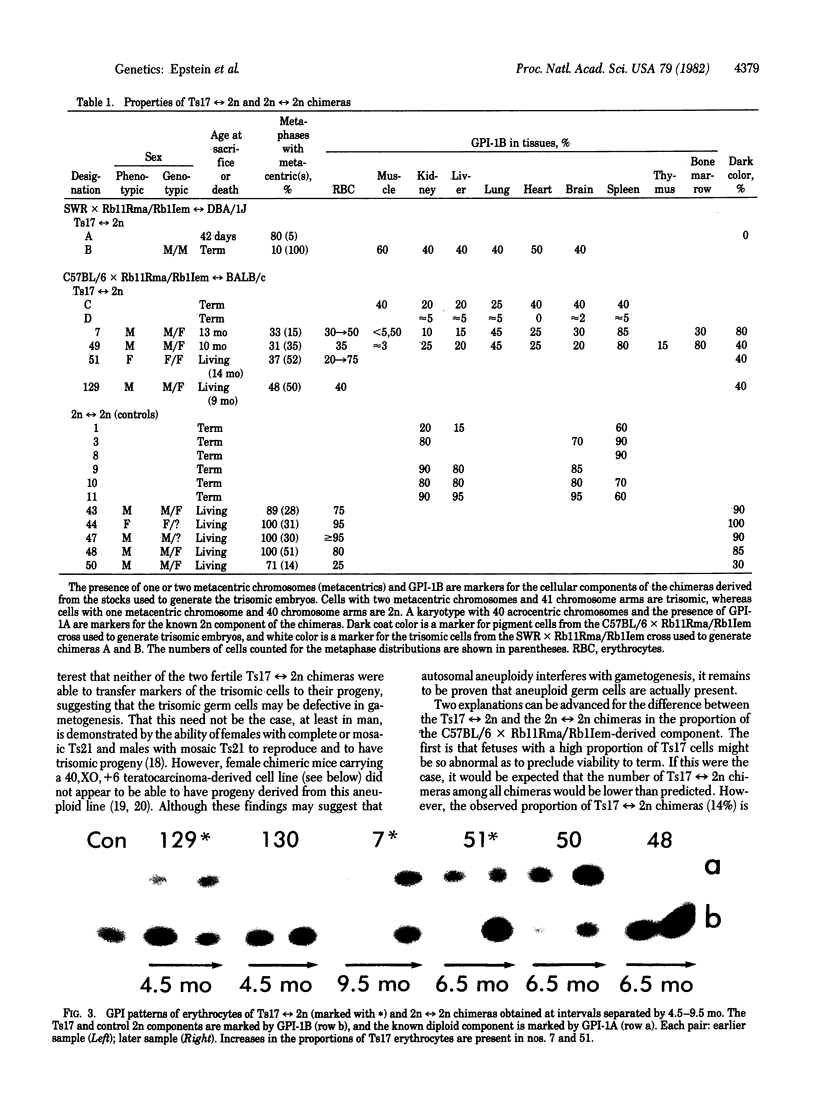

Aneuploid mouse embryos and fetuses are an important system for investigating the pathogenesis of the developmental and functional consequences of chromosome imbalance in mammals. However, the fact that almost all mouse aneuploids die in embryonic or fetal life restricts their usefulness for studies of loci and functions that are expressed only after birth. As an approach to rescuing aneuploid cells, we have prepared chimeras by aggregating aneuploid embryos with diploid embryos at the 8-16 cell stage. This technique has allowed us to produce trisomy 17 reversible diploid (Ts17 reversible 2n) chimeras containing cells of a trisomic state, which is ordinarily lethal at 10-12 days of gestation. All of the analyzed organs from the chimeras, including brain, liver, kidney, lung, muscle, heart, thymus, spleen, bone marrow, blood, and skin, contained both Ts17 and 2n cells. The proportion of Ts17 cells in each organ as estimated from coat color, enzyme markers (glucosephosphate isomerase), and karyotypes ranged from 5% to 85%, most commonly 20-40%. This is in contrast to the control 2n reversible 2n chimeras in which the 2n component on the same genetic background as the Ts17 generally comprised 60-90% of the cell population. The growth rates of the living Ts17 reversible 2n chimeras were in the lower half of the normal range, and the oldest animals are now age 14 mo. No progeny were obtained from Ts17 germ cells in the two fertile T217 reversible 2n chimeras. In comparison with analogous human situations, it is striking that, except for a kink in the tail of one living animal, none of the Ts17 reversible 2n chimeras had any discernible structural abnormalities. Our findings indicate that it is feasible to rescue cells from autosomal aneuploidies that otherwise result in early fetal death.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Cronmiller C., Mintz B. Karyotypic normalcy and quasi-normalcy of developmentally totipotent mouse teratocarcinoma cells. Dev Biol. 1978 Dec;67(2):465–477. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey M. J., Martin D. W., Jr, Martin G. R., Mintz B. Mosaic mice with teratocarcinoma-derived mutant cells deficient in hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5564–5568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicher E. M., Hoppe P. C. Use of chimeras to transmit lethal genes in the mouse and to demonstrate allelism of the two X-linked male lethal genes jp and msd. J Exp Zool. 1973 Feb;183(2):181–184. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401830205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein C. J., Travis B. Preimplantation lethality of monosomy for mouse chromosome 19. Nature. 1979 Jul 12;280(5718):144–145. doi: 10.1038/280144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein C. J., Tucker G., Travis B., Gropp A. Gene dosage for isocitrate dehydrogenase in mouse embryos trisomic for chromosome 1. Nature. 1977 Jun 16;267(5612):615–616. doi: 10.1038/267615a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishler K., Koch R., Donnell G. N. Comparison of mental development in individuals with mosaic and trisomy 21 Down's syndrome. Pediatrics. 1976 Nov;58(5):744–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forejt J., Capková J., Gregorová S. T(16: 17)43H translocation as a tool in analysis of the proximal part of chromosome 17 (including T-t gene complex) of the mouse. Genet Res. 1980 Apr;35(2):165–177. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300014026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gropp A., Giers D., Kolbus U. Trisomy in the fetal backcross progeny of male and female metacentric heterozygotes of the mouse. i. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1974;13(6):511–535. doi: 10.1159/000130304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gropp A., Kolbus U., Giers D. Systematic approach to the study of trisomy in the mouse. II. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1975;14(1):42–62. doi: 10.1159/000130318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gropp A., Putz B., Zimmermann U. Autosomal monosomy and trisomy causing developmental failure. Curr Top Pathol. 1976;62:177–192. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-66458-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst E. W., Pluznik D. H., Gropp A., Uthgennant H. Trisomic hemopoietic stem cells of fetal origin restore hemopoiesis in lethally irradiated mice. Science. 1981 Mar 13;211(4487):1175–1177. doi: 10.1126/science.7466390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T. Y., Markert C. L. Manufacture of diploid/tetraploid chimeric mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Oct;77(10):6012–6016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.10.6012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBurney M. W. Clonal lines of teratocarcinoma cells in vitro: differentiation and cytogenetic characteristics. J Cell Physiol. 1976 Nov;89(3):441–455. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040890310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz B., Palm J. Gene control of hematopoiesis. I. Erythrocyte mosaicism and permanent immunological tolerance in allophenic mice. J Exp Med. 1969 May 1;129(5):1013–1027. doi: 10.1084/jem.129.5.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas J. F., Avner P., Gaillard J., Guenet J. L., Jakob H., Jacob F. Cell lines derived from teratocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 1976 Nov;36(11 Pt 2):4224–4231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou V. E., Gardner R. L., McBurney M. W., Babinet C., Evans M. J. Participation of cultured teratocarcinoma cells in mouse embryogenesis. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1978 Apr;44:93–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton G. R., Silver M. F., Allison A. C. Comparison of cell cycle time in normal and trisomic cells. Humangenetik. 1974;23(3):173–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00285103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putz B., Krause G., Garde T., Gropp A. A comparison between trisomy 12 and vitamin A induced exencephaly and associated malformations in the mouse embryo. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1980;386(1):65–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00432645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi V. M. Trisomy 8: an international study of 70 patients. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1977;13(3C):171–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E. L., Epstein C. J. Replication rate and lifespan of cultured fibroblasts in Down's syndrome. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1972 Dec;141(3):1092–1094. doi: 10.3181/00379727-141-36940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner C. M., McIvor J. L., Stephens T. J. Chimeric drift in allophenic mice. Differentiation. 1977 Oct 20;9(1-2):11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1977.tb01513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J. D. Red blood cell selection in chimeric mice. Exp Hematol. 1977 Jan;5(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White B. J., Tjio J. H., Van de Water L. C., Crandall C. Trisomy 19 in the laboratory mouse. I. Frequency in different crosses at specific developmental stages and relationship of trisomy to cleft palate. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1974;13(3):217–231. doi: 10.1159/000130274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White B. J., Tjio J. H., Van de Water L. C., Crandall C. Trisomy 19 in the laboratory mouse. II. Intra-uterine growth and histological studies of trisomics and their normal littermates. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1974;13(3):232–245. doi: 10.1159/000130275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Someren H., Beijersbergen van Henegouwen H., Los W., Wurzer-Figurelli E., Doppert B., Vervloet M., Meera Khan P. Enzyme electrophoresis on cellulose acetate gel. II. Zymogram patterns in man-Chinese hamster somatic cell hybrids. Humangenetik. 1974;25(3):189–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00281426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]