Abstract

Study Objectives:

To evaluate the long-term (8 months) efficacy of zolpidem in adults with chronic primary insomnia using polysomnography.

Design:

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial.

Setting:

Sleep disorders and research center.

Participants:

Healthy participants (n = 91), ages 23-70, meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for primary insomnia.

Interventions:

Nightly zolpidem, 10 mg (5 mg for patients > 60 yrs) or placebo 30 minutes before bedtime for 8 months.

Measurements and Results:

Polysomnographic sleep parameters and morning subject assessments of sleep on 2 nights in months 1 and 8. Relative to placebo, zolpidem significantly increased overall total sleep time and sleep efficiency, reduced sleep latency and wake after sleep onset when assessed at months 1 and 8. Overall, subjective evaluations of efficacy were not shown among treatment groups.

Conclusions:

In adults with primary insomnia, nightly zolpidem administration remained efficacious across 8 months of nightly use.

Clinical Trial Information:

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01006525; Trial Name: Safety and Efficacy of Chronic Hypnotic Use; http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01006525.

Citation:

Randall S; Roehrs TA; Roth T. Efficacy of eight months of nightly zolpidem: a prospective placebo-controlled study. SLEEP 2012;35(11):1551-1557.

Keywords: Primary insomnia, zolpidem, hypnotics, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Insomnia is defined as difficulty initiating sleep, maintaining sleep, waking too early or nonrestorative sleep despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep.1 The sleep disturbances associated with insomnia can result in daytime impairments and/or distress. Chronic insomnia represents a more complex condition than acute transient insomnia with symptoms occurring 3 or more times per week and lasting 30 days or more.2 Retrospective studies indicate severe insomnia symptoms can last 1 or more years2 to decades, with periods of relapse and remission.3

Many insomnia patients take prescription hypnotics longer than the 2-4 weeks indication, with over half taking hypnotics longer than 4 weeks, due to persistent symptomatology.4–7 Given the prevalence of long-term pharmacological insomnia treatment, long-term efficacy studies are warranted.

Nonbenzodiazepine receptors antagonists (nonBzRA) are among the approved pharmacological treatments for insomnia management. Substantial evidence supports short-term efficacy of nonBzRA hypnotics. Several long-term pharmacotherapy studies using nonBzRA for insomnia show sustained efficacy ≥ 6 months with minimal adverse effects. Patient reports from placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical studies showed that eszopiclone sustained efficacy up to 6 months,8,9 and showed sustained efficacy during a 6 months open label extension.10 Eszopiclone significantly decreased sleep latency, wake after sleep onset (WASO), the number of awakenings, and increased total sleep time (TST) during the open label extension relative to their final double-blind month baseline. Nightly eszopiclone for 12 months showed no evidence of tolerance or systematic adverse effects.10

Similar results of sustained efficacy were shown with nightly ramelteon (8 mg) administration for 6 months. Ramelteon significantly reduced polysomnograph (PSG)-defined latency to persistent sleep (LPS) throughout the 6-month treatment and increased TST only at week 1 relative to placebo. No evidence of tolerance was reported and the adverse event profile was consistent with that of placebo. With discontinuation, ramelteon showed no rebound insomnia or withdrawal effects.11

A 6- to 12-months open-label trial of zaleplon (5 to 10 mg) in older chronic insomniac patients (mean age 72.5 y) self reported significant decreases in LPS and nocturnal awakenings and increased sleep duration relative to baseline at monthly assessments.12 Further, zaleplon discontinuation was not associated with rebound insomnia. The pattern of treatment-related adverse events was consistent with that observed in hypnotic short-term trials and was not substantial, given the varied comorbid medical conditions and medications. Although the evidence supports the effectiveness of long-term zaleplon use, the authors noted that placebo-controlled, double-blind studies are needed to confirm these results and that of other nonBzRAs to confirm findings of extended efficacy.12

Given the evidence of long-term pharmacotherapy use in insomnia, it is of interest to determine the long-term efficacy of zolpidem. Few controlled studies exist in which hypnotic efficacy is evaluated beyond 6 months using PSG-defined measures of sleep. In clinical practice, 6 months of zolpidem treatment is shown to be efficacious and safe.13 Placebo-controlled trials show no signs of withdrawal, tolerance, rebound insomnia, or next-morning residual effects at recommended therapeutic doses.13–16

Although all medications contain risk, there must be a balance between the risks and benefits. Similarly, hypnotic use is not without risks. Warnings of severe allergic reactions (anaphylaxis, angioedema) and complex sleep related behaviors (e.g., sleep eating, sleep walking, sleep sex and/or sleep driving) appear on all sedative hypnotics in the United States. These rare events most often result from misuse, abuse of hypnotic drugs and/or from multiple drug interactions.

The current study objective was to assess zolpidem efficacy for 8 months (10 mg, 5 mg for patients > 60 y) in a double blind, placebo-controlled investigation in primary insomniacs using both objective PSG and subject assessments.

METHODS

Participants

Participants met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria for primary insomnia. All participants were in good psychiatric and physical health, as determined by the screening procedures detailed below. The Institutional Review Board of the Henry Ford Health System (HFHS) reviewed and approved study protocol, and a Data Safety Monitoring Board oversaw study conduct. All participants provided informed consent and were monetarily compensated each month upon the completion of scheduled protocol activities (monthly clinic visit, laboratory sleep study and/or completion of 4 consecutive weekly telephone interactive voice response calls for medication compliance).

General Health and Psychiatric Screening

Prospects were respondents to media advertisements and study participant referrals for individuals having “difficulty falling and/or staying asleep.” Responses to a telephone interview regarding sleep, current and past physical and mental health, drug and alcohol consumption and/or abuse served as the initial screen. Those passing the telephone interview were scheduled for a clinic visit to further determine study eligibility and provide informed consent.

Eligibility requirements included good general physical and mental health as determined by physical examination, urinalysis and blood chemistry profiles. Those with acute or unstable illnesses, or illnesses with a potential to affect sleep, and conditions which could affect the pharmacokinetics of zolpidem, were excluded. Subjects using central nervous system acting medications were also excluded. The Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression were used to exclude those with psychiatric disorders and/or drug and alcohol dependence.

Those who consumed > 14 standard alcoholic drinks per week, > 300 mg/day of caffeine, inability to refrain from smoking during overnight laboratory visits, use of illegal drugs within the past 2 years, and those failing the urine drug screen were excluded. Pregnant or lactating females were excluded from study participation. Non-pregnant females were required to use standard birth control methods. A sleep history was taken to confirm primary insomnia diagnoses and to exclude sleep and circadian rhythm disorders. A 2-week sleep diary determined habitual bedtime and the PSG bedtime was calculated using the sleep diary mean time-in-bed midpoint. Four hours were added to each side of the midpoint to create an 8 hours bedtime, which minimized disruption of circadian rhythms. Participants passing the physical and mental health screening underwent an 8 hours screening PSG.

Screening PSG and Study PSG Procedures

Subjects reported to the sleep laboratory approximately 2 hours before bedtime. Thirty minutes before bed, participants received a placebo capsule, in order to assess baseline sleep measures. The 8 hours screening PSG included standard central (C3-A2) and occipital (Oz-A2) electroencephalograms (EEGs), bilateral horizontal electroculograms (EOG), submental electromyogram (EMG), and electrocardiogram (ECG) recorded with a V5 lead. In addition, on the screening night, airflow was monitored with oral and nasal thermistors and leg movements were monitored with an electrode placed over the left tibialis muscle. Respiration and tibialis EMG recordings were scored for apnea and leg movement events, and event frequencies were tabulated.17,18 Subjects with respiratory disturbances (apnea-hypopnea index [AHI] > 10) or with periodic limb movement arousal indices (PLMAI) > 10/h were excluded from the study. Subjects were required to demonstrate a screening sleep efficiency ≤ 85% (total sleep time/time in bed) and have no other sleep disorders. Subsequent study 8-h PSGs excluded airflow and leg monitoring.

The standard Rechtschaffen and Kales19 methods for sleep scoring were used. All PSGs were scored in 30-sec epochs with scorers blind to treatment conditions. Scorers maintained 90% interrater reliability.

Medication Preparation

The HFHS Research Pharmacy prepared study medication in size #1 clear or opaque capsules. Zolpidem (10 mg) clear capsules contained lactose and zolpidem and opaque capsules contained 5 mg of zolpidem (for participants > 60 years old). Placebo capsules were identical in appearance to zolpidem capsules, containing lactose only. Participants passing the sleep screen were randomly assigned to placebo or zolpidem (10 mg or 5 mg) administration. In the sleep laboratory, study medication was administered 30 min prior to the PSG.

Study Design

PSGs were conducted on 2 consecutive treatment nights during months 1 (nights 1 and 2) and 8. A subset of participants also took part in behavioral and physical dependence liability assessments.20,21 Participants and researchers were blind to treatment conditions. (N = 17; zolpidem group) were assessed for rebound insomnia. Rebound assessments, involving placebo substitution for 7 nights, occurred after efficacy assessments in month 1 and in month 4. The efficacy assessments of the current study occurred prior to placebo substitution.

Subjective sleep measures were obtained the morning following the PSG. Participants completed a post-sleep questionnaire on a laptop computer. The post-sleep questionnaire queried for estimates in minutes to fall asleep, hours slept, and minutes awake after falling asleep. Sleep quality was measured using a 4 point Likert scale, where 0 = poor, 1 = fair, 2 = good, 3 = excellent. A visual analogue scale measured sleepiness and the ability to concentrate. Each analogue scale required placement of a mark on a continuous line measuring 100 mm, between 2 endpoint word descriptors. The mark corresponded to scores between 0 and 100. The word descriptors for ease in falling asleep were very easy (scored 0) to not at all easy (scored 100). Descriptors for the sleepiness scale were very sleepy and not at all sleepy. For the ability to concentrate, the word descriptors were not at all easy (to concentrate) and on the opposite end were very easy (to concentrate).

At home, participants were instructed to take study medication nightly, 30 min before bed on nights they were able to remain in bed for 7 to 8 hours. Furthermore, participants were instructed to abstain from alcohol 3 to 4 hours prior to bedtime. Participants reported to scheduled monthly clinic visits to assess medication compliance, changes in and/or the emergence of any new physical and/or psychological signs and symptoms or adverse events. An approximate 30-day supply of study medication was dispensed at each monthly clinic visits.

Study Medication Compliance

A telephone interactive voice response system (IVRS) captured patient reported data regarding medication compliance. Study participants were instructed to call a toll-free telephone number on a predetermined day of the week. The participant would answer a series of questions concerning their sleep and the number of capsules taken in the past week. The IVRS reports were confirmed during monthly clinic visits. Medication adherence was assessed by summing weekly capsule report count for each study month. The capsule count was divided by the number of days per month and multiplied by 100 to yield the percentage of capsule consumed each study month.

Analyses

The primary efficacy parameters were PSG defined measures of sleep efficiency (SE: sleep time/time in bed × 100%), TST (total sleep time), LPS (latency to 10 min continuous sleep), and WASO. While time in bed was fixed, both TST and SE measures are presented for those who are more or less accustomed to one or the other of these outcome measures. Subjective sleep efficacy measures included sleep latency (sSL), wake after sleep onset (sWASO), and total sleep time (sTST). Secondary PSG measures included the percentage of standard sleep stages. All dependent measures were the baseline night and the mean of 2 consecutive nights in months 1 and 8. Data were analyzed using repeated measures 2 × 3 multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) with drug (placebo and zolpidem) as a between-subject factor and time (baseline, and months 1 and 8) as within-subject factors.

Intent to treat analysis was performed in which data was carried forward to month 8 in those who discontinued. The data from this analysis was similar to the findings of the current study and the results were not included.

RESULTS

Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

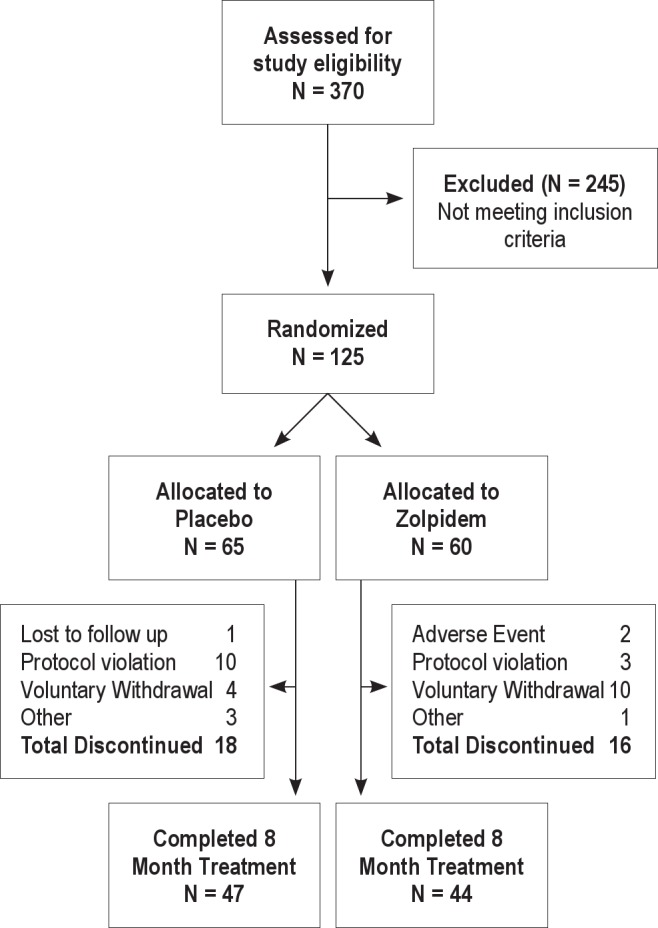

Of the 370 participants undergoing the clinical and sleep screening, 125 met entry criteria and were randomly assigned to receive placebo (N = 65) or zolpidem (N = 60); see Figure 1. Of those failing the screening procedures, 39% were for mental health and/or drug abuse disorders, 17% for chronic medical illnesses, 18% failed the sleep screen (having sleep apnea or screening SE > 85%), and 26% for miscellaneous reasons (including loss of contact, lack of interest or scheduling conflicts).

Figure 1.

Participant disposition diagram over the 8-month clinical trial.

Qualified participants were randomized to study treatment groups with 91 (72.8%) completing the 8-month double-blind treatment (47 in the placebo group and 44 in the zolpidem group). Of the 34 discontinuations, the most common reason for study departure was voluntary withdrawal and protocol violation. Within the placebo group, 56% (10 of 18) of the discontinuations were due to protocol violations, which included noncompliance to protocol, no-show for clinic or laboratory appointments, loss of contact and/or personality conflicts with research and/or technical staff. Within the zolpidem group, 63% (10 of 16) of the discontinuations were due to voluntary withdrawal, which included study interference with social and/or family obligations, job promotion and/or relocation to another state. Two adverse events (dizziness and heart sensations) occurred within the zolpidem group and the affected participants requested to discontinue study participation. Within the placebo group, 3 discontinuations occurred following difficulty adapting to head electrodes, a heart attack (unrelated to study), and consistent technical difficulty recording and scoring a reliable PSG record due to a tremor.

Participant's demographics were similar between both treatment groups. The overall average age was 50.4 years (range: 23 to 70 years), with 59.3% being female. Participants in the placebo and zolpidem groups had similar alcohol and caffeine consumption, nicotine use, and past and/or current drug use (Table 1). Screening sleep measurements did not differ significantly between the placebo and zolpidem groups at baseline (Table 1). The overall average age of insomnia onset and the average duration of insomnia symptoms were 38.0 years and 12.3 years, respectively. There were no significant differences in the PSG-defined TST, SE, LPS, and WASO between the treatment groups at baseline screening (Table 1). Across both groups, the average PSG-defined TST was 357.27 min (5.95 h), LPS was 41.28 min, and WASO was 98.86 min at baseline.

Table 1.

Treatment group composition at screening

Table 2 presents study medication adherence complied from the IVRS. Overall, participants reported taking weekly averages between 5.73 ± 1.7 to 6.29 ± 1.08 capsules on non-laboratory weeks. Monthly adherence, complied from weekly IVRS reports, showed that participants reported taking 82% to 88% of study medication each month. There were no significant differences in the number of capsules taken among study weeks 1 through 32 (P = 0.926) or study months 1 through 8 (P = 0.390). No significant differences were seen between treatment groups across study weeks (P = 0.439) or study months (P = 0.793).

Table 2.

Treatment compliance of study groups by months

Objective Assessments of Zolpidem Efficacy

Zolpidem significantly increased TST (F1,88 = 12.932; P = 0.001) and a main effect of time (F2,176 = 31.873; P = 0.0001) and a drug × time interaction (F2,176 = 5.112; P = 0.007) was also found (Table 3). Zolpidem produced a significantly greater increase in TST of 58 min relative to baseline and of 36 min relative to placebo at Month 1, and it continued to show sustained increases in TST at Month 8. At Month 8, zolpidem increased TST by 51 min relative to baseline and by 40 min relative to placebo. Compared to baseline, placebo increased TST by 28 min in Month 1 and by 17 min in Month 8. The time effect was reflected in baseline to Month 1 and 8 differences, as there were no significant differences in Month 1 versus Month 8.

Table 3.

Polysomnographic measures of efficacy

Zolpidem produced a significant increase in SE (F1,88 = 12.932; P = 0.001) and also a main effect of time (F2,176 = 31.873; P = 0.001) and a time × drug interaction (F2,176 = 5.112; P = 0.007) was found. Improvements in SE were greater in the zolpidem group relative to the placebo group when compared to baseline. Zolpidem significantly increased SE by 11.4% and 10.8% relative to baseline in months 1 and 8, respectively (F1,88 = 6.395; P = 0.0312) and produced increases of 7% relative to placebo in both months. In contrast, placebo showed increases in SE of 6.2 and 5.2% relative to baseline in Months 1 and 8. The time effect was reflected in baseline to Month 1 and 8 differences, as there were no significant differences between Month 1 and 8.

Sleep Initiation and Maintenance

Significant main effects of zolpidem (F1,88 = 15.273; P = 0.001) and time (F2,176 = 24.579; P = 0.001) occurred for LPS, with a nonsignificant interaction (P = 0.374). Main effects of zolpidem (F1,88 = 5.416; P = 0.022), time (F2,176 = 25.828; P = 0.001), with a time × drug interaction (F2,176 = 3.165; P = 0.026) on WASO were found. Zolpidem decreased WASO by 40 min relative to baseline in both Months 1 and 8. WASO in the zolpidem group was ≤ 20 min in the placebo group at Months 1 and 8. The placebo group showed a decrease in WASO of 21.5 min in Month 1 and of 15.4 min in Month 8. Again, the time effect was reflected in baseline to Month 1 and 8 differences, as there were no differences between Months 1 and 8.

Sleep Architecture

There were no significant changes in the percentage of time spent in sleep stages 1, 3-4, and REM with zolpidem relative to placebo (see Table 4). Zolpidem was associated with a small but significant increases in the percentage of stage 2 sleep at month 1 relative to placebo (F1,88 = 5.281; P = 0.024), with no other significant main effects or interactions.

Table 4.

Polysomnographic measures of sleep staging

Subjective Assessments of Efficacy

Table 5 presents subjective assessments of zolpidem efficacy. Zolpidem significantly decreased sSL (F1,85 = 6.983; P = 0.010) and improved the ease in falling asleep (F1,85 = 5.418; P = 0.022) relative to placebo. No significant differences were seen between treatment groups on subjective assessments of WASO, TST, and sleep quality. There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups on morning self-rated measures of concentration and sleepiness.

Table 5.

Subjective sleep measures

Correlations between Subjective and Objective Measures

Subjective and objective measures of sleep latency (Mt1: r = 0.570; Mt8: r = 0.487), WASO (Mt1: r = 0.514; Mt8: r = 0.279) and TST (Mt1: r = 0.371; Mt8: r = 0.256) were significantly correlated with each other at Months 1 and 8 (all P ≤ 0.017).

Overall sleep quality did not correlate with PSG defined measures of sleep. The treatment groups differed in their correlations of sleep quality and subjective measures of sleep efficacy (Table 6). At Month 1, sleep quality in the zolpidem group was significantly correlated with all subjective sleep measures. In contrast, sleep quality was significantly correlated with sTST, decreases in sleepiness, and the ability to concentrate in the placebo group. In Month 8, sleep quality was significantly correlated with all subjective sleep measures in both treatment groups. Additionally, sleep quality in the zolpidem group was significantly correlated with TST.

Table 6.

Correlation between sleep quality and subjective and objective sleep measures

DISCUSSION

This is the first double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized PSG trial evaluating eight months of nightly zolpidem treatment in primary chronic insomniacs. Zolpidem significantly increased total sleep time (TST) and sleep efficiency (SE), decreased latency to persistent sleep (LPS) and wake after sleep onset (WASO), when assessed at Months 1 and 8 relative to baseline and placebo. Previous studies assessing dependence liability of nightly zolpidem at months 1, 4, and 12, exhibited minimal evidence of dose-escalation20 or rebound insomnia.21 These results complement and extend previous shorter-term studies (≤ 6 months) of sedative hypnotic use in chronic insomnia management by showing sustained zolpidem efficacy with nightly usage for eight months.

The sustained efficacy of zolpidem (and similar hypnotics) may explain the long duration of sedative-hypnotics use in insomnia patients. It is often assumed that long-term use per se, is evidence of dependence. But the use of sedative hypnotics for chronic insomnia longer than what has been traditionally recommended may reflect the continued effectiveness of these drugs in patients with persistent symptomatology. That is to say, long-term use, of itself, is not evidence of dependence.

Overall, no group differences were not shown in subjective evaluations of zolpidem efficacy. Sleep state misperception may explain the discrepancy between subjective and PSG-defined measures of sleep efficacy. Overall, both treatment groups tended to overestimate SL and underestimate WASO, and yet were able to accurately indicate their sleep duration (TST). The results of the current study are consistent with previous studies in which insomniacs on zolpidem showed objective decreases in sleep latency with overestimates of sleep latency.22

On zolpidem, perceived sleep quality was associated with all subjective measures of sleep efficiency. Sleep quality was significantly correlated with positive perceptions of sleeping well at Months 1 and 8 in the zolpidem group. For example, increases in sleep quality positively correlated with increases in daytime concentration and alertness (decreased sleepiness). This finding may result from decreases in sleep initiation and nocturnal awakenings. It is of interest that in Month 8, sleep quality within the placebo group closely mimics that of the zolpidem group. The placebo group did show some improvements in sleep, which may be attributed to adherence to the study protocol procedures and/or nonspecific improvements associated with participating in a clinical trial.

This study has a number of limitations. First, the current study includes no assessments of zolpidem efficacy between Months 2 and 7. Previous research has established that zolpidem remains efficacious from 60 to 180 days; in light of the current findings, it is doubtful that deterioration of efficacy occurred during the non-assessed months. Second, the participants in this study were a highly select population of insomniacs. Participants were excluded for primary sleep disorders and chronic medical and psychiatric disorders. Given the primary purpose of this clinical trial, the assessment of abuse liability with chronic hypnotic use, we wanted to study that risk in a best-case population, that is, in primary insomniacs. The impact of recruiting such a homogenous population on this study's efficacy results is likely that it produced a reduction of variability and thereby the ability to show strong evidence of sustained PSG efficacy. The other important screening criterion was that the screening PSG must show a sleep efficiency ≤ 85%. This criterion assured that we were studying severe insomniacs in whom we felt abuse risk would be high. In actuality, only 12% of the participants failed the PSG screening due to the ≤ 85% criterion.

Third, the treatment groups were not significantly different from each other in study attrition, yet the reasons for discontinuations were unbalanced. The placebo group had more protocol violations than the zolpidem group. These violations may reflect the participant's ability to discern that the study medication had little beneficial effect on their sleep and were more likely to stop taking study medication, disregard clinic/laboratory appointments, and have negative emotional temperaments. In the zolpidem group, majority of the discontinuations were due to voluntary withdrawals. Although, the medication may have had beneficial effects on sleep, extenuating circumstances such as family, work or social obligations interfered with monthly clinic and/or laboratory visits.

Lastly, treatment effects on the morning measures of concentration and sleepiness were not found. Both of these measures were assessed on a 4-point Likert-Scale, which can limit responder's ability to show their true state. A larger range of response options (i.e., 10-point scale or a visual analogue scale) could probably better detect changes, if any, as they occur. Additionally, these measures of daytime function (concentration and sleepiness) were based upon a limited subjective evaluation (4-point Likert scale) vs. an actual behavioral assessment specific to each measure. Given these study limitations, the results of this study provide valuable insight into the efficacy of long-term nightly hypnotic use.

In conclusion, nightly administration of zolpidem for up to eight months proved to be efficacious in treating chronic insomnia. However, sleep improvement from zolpidem did not result in self-reported benefit in subjective measures of zolpidem efficacy relative to placebo.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Roth has served as a consultant for Abbott, Accadia, Acogolix, Acorda, Actelion, Addrenex, Alchemers, Alza, Ancel, Arena, AstraZeneca, Aventis, AVER, Bayer, BMS, BTG, Cephalon, Cypress, Dove, Eisai, Elan, Eli Lilly, Evotec, Forest, Glaxo Smith Kline, Hypnion, Impax, Intec, Intra-Cellular, Jazz, Johnson and Johnson, King, Lundbeck, McNeil, MediciNova, Merck, Neurim, Neurocrine, Neurogen, Novadel, Novartis, Ocera, Orexo, Organon, Otsuka, Prestwick, Proctor and Gamble, Pfizer, Purdue, Resteva, Roche, Sanofi, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Servier, Shire, Somaxon, Somnus, Steady Sleep Rx, Syrex, Takeda, Transcept, Vanda, Ventus, Vivometrics, Wyeth, Yamanuchi, and Xenoport. He has served on speakers bureau for Cephalon, Sanofi, and Sepracor. He has received research support from Aventis, Cephalon, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck, Neurocrine, Pfizer, Sanofi, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Somaxon, Somnus, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Ventus, Wyeth, and Xenoport. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Henry Ford Sleep Center technical staff for nocturnal recordings as well as G. Koshorek, S. Cameron, A. Rojas, and D. Ditri for their meticulous scoring of PSG records. Financial support for this study was provided by NIDA grant # R01DA17355 awarded to Dr. Roehrs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5 Suppl):S7–S10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sateia MJ, Doghramji K, Hauri PJ, Morin CM. Evaluation of chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2000;23:1–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sleep; National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference Statement on Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults; June 13-15, 2005; 2005. pp. 1049–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krakow B, Ulibarri VA, Romero EA. Patients with treatment-resistant insomnia taking nightly prescription medication for sleep: a retrospective assessment of diagnostic and treatment variables. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12:e1–e10. doi: 10.4088/PCC.09m00873bro. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krakow B, Ulibarri VA, Romero EA. Persistent insomnia in chronic hypnotic users presenting to a sleep medical center: retrospective chart review of 137 consecutive patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:734–41. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181f4aca1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendelson WB, Roth T, Cassella J, et al. The treatment of chronic insomnia: drug indications, chronic use and abuse liability. Summary of a 2001 New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit Meeting Symposium. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8:7–17. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(03)00042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenthal LD, Dolan DC, Taylor DJ, Grieser E. Long term follow up of patients with insomnia. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2008;21:264–5. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2008.11928409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh JK, Krystal AD, Amato DA, et al. Nightly treatment of primary insomnia with eszopiclone for six months: effects on sleep, quality of life, and work limitations. Sleep. 2007;30:959–68. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.8.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krystal AD, Walsh JK, Laska E, et al. Sustained efficacy of eszopiclone over 6 months of nightly treatment: results of a randomized, doubled blinded, placebo controlled study in adults with chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2003;26:793–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth T, Walsh JK, Krystal A, et al. An evaluation of the efficacy and safety of eszopiclone over 12 month in patients with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep Med. 2005;6:487–95. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer G, Wang-Weigand S, Roth-Schechter B, Lehmann R, Staner C, Partinen M. Efficacy and safety of 6-month nightly ramelteon administration in adults with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep. 2009;32:351–60. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ancoli-Israel S, Richardson GS, Mangano RM, et al. Long-term use of sedative hypnotics in older patients with insomnia. Sleep Med. 2005;6:107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlich D, L'Heriter C, Coquelin JP, Attali P, Kryreub HJ. Long-term treatment of insomnia with zolpidem: a multicentre general practitioner study of 107 patients. J Int Med Res. 1991;19:271–9. doi: 10.1177/030006059101900313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scharf MB, Roth T, Vogel GW, Walsh JK. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study evaluating zolpidem in the treatment of chronic insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:192–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maarek L, Cramer P, Attali P, Coquelin JP, Morselli PL. The safety and efficacy of zolpidem in insomniac patients: a long-term open study in general practice. J Int Med Res. 1992;20:162–70. doi: 10.1177/030006059202000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JC, Walsh JK, Scharf MB, Roehrs T, Roth T, Vogel GW. Minimal rebound insomnia after treatment with 10-mg zolpidem. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1997;20:116–25. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bornstein SK. Respiratory monitoring during sleep: polysomnography. In: Guilleminault C, editor. Sleeping and waking disorders: indications and techniques. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co; 1982. pp. 183–212. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coleman RM. Periodic movements I sleep (nocturnal myoclonus) and restless legs syndrome. In: Guilleminault C, editor. Sleeping and waking disorders: indications and techniques. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co; 1982. pp. 183–212. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. Washington DC: Public Health Service, U.S. Government Printing Office; 1968. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques, and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roehrs T, Randall S, Harris E, Maan R, Roth T. Twelve months of nightly zolpidem does not lead to dose escalation: a prospective placebo-controlled study. Sleep. 2011;34:207–12. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roehrs TA, Randall S, Harris E, Maan R, Roth T. Twelve months of nightly zolpidem does not lead to rebound insomnia or withdrawal symptoms: A prospective placebo controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2011 Oct 16; doi: 10.1177/0269881111424455. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kryger MH, Steljes D, Pouliot Z, Neufeld H, Odynski T. Subjective versus objective evaluation of hypnotic efficacy: experience with zolpidem. Sleep. 1991;14:399–407. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.5.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]