Coronary artery anomalies include the anomalies of origin, termination, and structure or course. Coronary artery fistulas (CAFs) are classified as the anomalies of termination and are considered a major congenital anomaly and are in the subgroup of acyanotic heart disease.1

Atrial septal defect

Ventricular septal defect

Patent ductus arteriosus

Aortic stenosis

Pulmonary stenosis

Parachute mitral valve

Coronary artery fistula

Anomalies of great veins

Definition

A CAF is a sizable communication between a coronary artery, bypassing the myocardial capillary bed and entering

History

Maude Abbott in 1908 discussed the first pathological account, and Bjork and Crafoord in 1947 performed the first surgery.4

Most CAFs are small and do not cause any symptoms and problems. When a fistula reaches two times a coronary size, signs and symptoms develop.

Pathophysiology

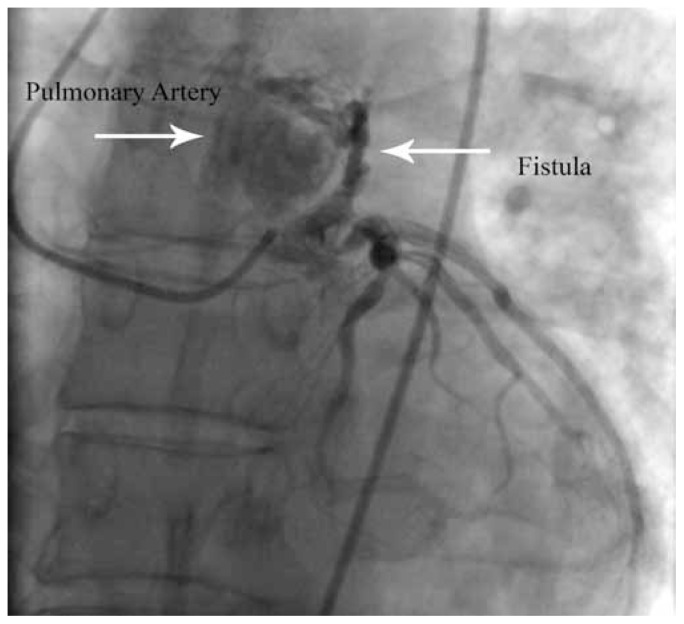

Large fistulas can cause the steal phenomenon and lead to myocardial ischemia by this segment of the coronary. This is due to a reduction in the flow distal to the site of the fistula as a result of diastolic pressure gradient and run-off from the coronary vasculature to a lower-pressure receiving cavity; therefore, the diastolic pressure progressively diminishes.5 To compensate that, the diameter of the coronary expands progressively and the ostia also becomes larger and larger (Figure 1). The myocardium beyond the fistula becomes ischemic, with an increasing oxygen demand during activity and exercises.

Figure 1.

A 44 years old patient with history of chest pain, acute myocardial infarction, low ejection-fraction, congestive heart failure, low flow to distal arteries and occasionally ventricular tachyarrhythmia. Site of fistula (left anterior descending coronary artery to pulmonary artery) is indicated by arrow

Progressive dilation may give rise to aneurysm formation, intimal ulceration, medial degeneration, intimal rupture, atherosclerotic deposition, calcification, side-branch obstruction, thrombosis, and, rarely, rupture.6

Factors to determine hemodynamic

Size

Resistance of the recipient chamber

Myocardial ischemia and occasionally high output congestive heart failure

CAFs could mimic the symptoms and pathophysiology of various heart diseases

To systemic veins like atrial septal defects

To the pulmonary artery like patent ductus arteriosus

To the left atrium like mitral regurgitation

To the left ventricle like aortic insufficiency

Major sites and origins

Right coronary artery: 40–60%

Left anterior descending artery: 30–60%

Termination sites

Ninety percent to the right side of the heart, left atrium, left ventricle, and coronary sinus, and most frequently to the pulmonary artery and rarely to the left ventricle and coronary sinusoids.

Fistulas are isolated or combined with other anomalies like pulmonary stenosis or atresia with an intact interventricular septum and in pulmonary artery branch stenosis, tetralogy of Fallot, coarctation of the aorta, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, and aortic atresia.7

Acquired fistulas

Trauma

Gunshot wound

Stab wound

Cardiac surgery

Cardiac catheterization

Angioplasty

Pacemaker implantation

Endomyocardial biopsy

Embryology

CAFs are thought to arise from the persistence of the sinusoidal connections between the lumen of the primitive tubular heart, which supply the myocardial blood flow,8 as well as from the faulty development of the distal branches of the coronary rectiform and vascular network.9

Frequency

0.2 – 0.4% of all congenital heart diseases and 50% of pediatric coronary anomalies are CAFs.10

Mortality/Morbidity

Fistula-related complications are present in 11% of patients younger than 20 years and in 35% of patients older than 20 years of age.11

Complications

Myocardial ischemia

Mitral valve papillary muscle rupture due to ischemia

Ischemic cardiomyopathy

Congestive heart failure due to volume overload

Bacterial endocarditis

Sudden cardiac death

Secondary aortic valve disease

Secondary mitral valve disease

Premature atherosclerosis

Endocarditis

Small fistulas are silent and are discovered by echocardiography and angiography. Large fistulas are discovered due to complications.12, 13

Race

No differences

Age

It could be discovered at any age.14 Large fistulas progressively enlarge and cause complications like congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, infectious endocarditis, aneurysm formation, rupture, and death mostly in older patients. Spontaneous closure is rare.

The mortality in the repair of CAFs is from 0% to 4%. Increase risk is in giant aneurysms and in the right coronary artery-to-left ventricle fistula.

Complications of surgery are myocardial ischemia and/or infarction (about 3%) and recurrence of the fistula (about 4% of patients).

Clinical History

Most children with small fistulas are asymptomatic, and a continuous murmur may be present in moderate-to-large sized fistulas

Symptoms such as irritability, diaphoresis, pallor, tachypnea, and exercise diaphoresis during feeding and tachycardia may be present.

Failure to thrive and low-output congestive heart failure

Older patients may present low-output congestive heart failure, arrhythmias, syncope, chest pain, and, rarely, endocarditis

Large fistulas develop high-output congestive heart failure and symptoms of dyspnea on exertion, angina, fatigue, and palpitations15

Physical examination

Most patients are asymptomatic in small fistulas

A continuous murmur may be present, while it may suggest patent ductus arteriosus in the lower sternal border; therefore, the location for the patent ductus arteriosus is atypical

Murmur may have diastolic accentuation, and it peaks in mid or end of diastole

It differs from patent ductus arteriosus, which has systolic accentuation

If the fistula connects to the left ventricle, an early diastolic murmur may be heard because of little flow during systole

Large fistulas give congestive heart failure signs

Wide pulse pressure and collapsing pulse may be present

Apex beat is diffuse and third heart sound (S3) may be heard

A holosystolic of mitral valve insufficiency may be present at the apex16

Causes

Congenital

Acquired by interventions

Differential diagnoses

Anomalous coronary artery from the pulmonary artery

Arteriovenous fistula

Myocardial infarction in childhood

Patent ductus arteriosus

Ruptured sinus of the sinus of the Valsalva

Aortopulmonary window

Systemic-to-pulmonary vein connection

Pulmonary vein stenosis

etc.

Work-up

Cardiac enzymes could be elevated

Brain natriuretic peptide may be elevated

Imaging studies

Chest radiography: can show cardiomegaly or normal chest

-

Electrocardiography: useful in showing

left ventricle hypertrophy

Ischemic changes

Arrhythmias

-

Echocardiography: helpful in diagnosing most fistulas and may reveal:

Left atrial and left ventricular enlargement as a result of a significant shunt

Dilatation of the coronary artery

High-volume flow by color-flow imaging

Drainage of the fistula

Holodiastolic run-off in the descending aorta

A squirt of the flow into a chamber

Dilated coronary sinus

Diagnosis

By cardiac catheterization and CT angiography,17, 18 occasionally by echocardiography.

Treatment

Medical care

In childhood, most patients with CAFs are asymptomatic; however, some patients may present with symptoms of dyspnea on exertion, increased fatigability, and, possibly, signs of high-output congestive heart failure. Rarely, patients may present with angina, palpitations, or signs of exercise-related coronary insufficiency. Direct medical treatment for symptomatic relief can be used until investigations and operative repair can be performed. Spontaneous closure may occur in small fistulas. Small fistulous connections in the asymptomatic patient may be monitored. Most lesions enlarge progressively and warrant operative repair, either by transcatheter or surgical techniques.

Diagnostic cardiac catheterization should be performed initially with or without additional therapeutic intervention. Initial diagnostic catheterization should both define the hemodynamic significance of the lesion and provide detailed angiographic assessment of the anatomy of the abnormality, in particular, the origin, course, regional narrowing, and the nature of the insertion.19

Surgical Care

Indications

Indications for surgical intervention are the same as those in embolization. Some fistulas are unsuitable for the transcatheter approach and are preferably addressed surgically. These CAFs may include fistulas with multiple connections, circuitous routes, and acute angulations that make catheter positioning difficult or impossible.20

Techniques

Surgical repair is usually approached via a median sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass. The feeding vessel should be identified, and its course and site of insertion should be delineated. The site of the presumed fistulous drainage should be identified prior to the institution of the cardiopulmonary bypass. Transesophageal echocardiographic imaging has been very useful in assisting in the location of the fistulous tract insertion. A typical procedure includes opening the chamber into which the fistula drains, identifying the fistula, and closing the site of drainage with a patch or suture. If the fistula enters the ventricle or if the feeding vessel is large, the coronary artery is opened, and the opening to the fistula is closed with a running suture. The arteriotomy is thereafter closed. Large aneurysms may require excision. Rarely, when the fistula is an end artery, it may be ligated with or without bypass.21

Small fistulas do not require any treatment. Large fistulas which are symptomatic and causing complications are approached currently by intervention using coils for closure or occasionally blocked by a covered stent.

Surgical intervention could require ligation closure of the fistula and is reported to have 4–8% mortality with a recurrent rate of about 4%.22

References

- 1.Kristensen T, Kofoed KF, Helqvist S, Helvind M, Søndergaard L. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) presenting with ventricular fibrillation in an adult: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;3:33–38. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Padfield GJ. A case of coronary cameral fistula. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:718–720. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bansal M, Golden AB, Siwik E. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from pulmonary artery with ostial stenosis. Circulation. 2009;120:e282. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Santis A, Cifarelli A, Violini R. Transcatheter closure of coronary artery fistula using the new Amplatzer vascular plug and a telescoping catheter technique. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2010;11:605–609. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283313504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arslan S, Gurlertop Y, Elbey MA, Karakelleoglu S. Multiple coronary-cameral fistulae causing angina pectoris. Tex Heart Inst J. 2009;36:622–623. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajaj S, Parikh R, Hamdan A, Bikkina M. Covered-stent treatment of coronary aneurysm after drug-eluting stent placement: case report and literature review. Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37:449–454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cottrill CM, Davis D, McMillen M, O’Connor WN, Noonan JA, Todd EP. Anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: significance of associated intracardiac defects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;6:237–242. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80282-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimitrakakis G, Von Oppell U, Luckraz H, Groves P. Surgical repair of triple coronary-pulmonary artery fistulae with associated atrial septal defect and aortic valve regurgitation. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008;7:933–934. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.181388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harikrishnan S, Bimal F, Tharakan JM. Coronary artery fistulae from single coronary artery in a patient with rheumatic mitral stenosis. Int J Cardiol. 2001;81:281–283. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(01)00546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saylan Čevik B, Tavlı V, Sarıtaş T, Oran I, Ergene O. Transcatheter closure of congenital coronary arteriovenous fistula using detachable balloon technique. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2010;10:463–464. doi: 10.5152/akd.2010.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohanty SK, Ramanathan KR, Banakal S, Muralidhar K, Kumar P. An interesting case of coronary cameral fistula. Ann Card Anaesth. 2005;8:152–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherwood MC, Rockenmacher S, Colan SD, Geva T. Prognostic significance of clinically silent coronary artery fistulas. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:407–411. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inamura N, Nakajima T, Kayatani F, Kawata H. Successful transcatheter coil embolization of coronary artery to left ventricular fistula associated with absent pulmonary valve with tricuspid atresia in early infancy. Circ J. 2004;68:1227–1229. doi: 10.1253/circj.68.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sapin P, Frantz E, Jain A, Nichols TC, Dehmer GJ. Coronary artery fistula: an abnormality affecting all age groups. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990;69:101–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdelmoneim SS, Mookadam F, Moustafa S, Zehr KJ, Mookadam M, Maalouf JF, Holmes DR. Coronary artery fistula: single-center experience spanning 17 years. J Interv Cardiol. 2007;20:265–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2007.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dourado LO, Góis AF, Hueb W, César LA. Large bilateral coronary artery fistula: the choice of clinical treatment. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009;93:e48–49. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2009000900020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alabdulgader AA. Noninvasive diagnosis of coronary artery fistula after cardiac surgery. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2002;10:339–341. doi: 10.1177/021849230201000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olearchyk AS, Runk DM, Alavi M, Grosso MA. Congenital bilateral coronary-to-pulmonary artery fistulas. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:233–235. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armsby LR, Keane JF, Sherwood MC, Forbess JM, Perry SB, Lock JE. Management of coronary artery fistulae. Patient selection and results of transcatheter closure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1026–1032. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01742-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wauthy P, Demanet H, Deuvaert FE. Surgical treatment of coronary artery fistula with aneurysm. Acta chir belg. 2003;103:532–533. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2003.11679485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahesh B, Navaratnarajah M, Mensah K, Amrani M. Treatment of high-output coronary artery fistula by off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting and ligation of fistula. Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9:124–126. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.203489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung DLC, Au WK, Cheung HHC, Chiu CSW, Lee WT. Coronary artery fistulas: long-term results of surgical correction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:190–195. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01862-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]