Abstract

In this paper we systematically describe the connection between immigration and fertility in light of the increasing nativist reaction to Hispanic groups. We follow a life-course perspective to directly link migration and fertility transitions. The analysis combines original qualitative and quantitative data collected in Durham/Chapel Hill, NC as well as national level information from the Current Population Survey. The qualitative data provides a person-centered approach to the connection between migration and fertility that we then extend in quantitative analyses. Results demonstrate that standard demographic measures that treat migration and fertility as separate processes considerably distort the childbearing experience of immigrant women, inflating fertility estimates for Hispanics as a whole. Once this connection is taken into consideration the fertility levels of Hispanic women are much lower than those reported with standard measures and the fertility-specific contribution of Hispanics to U.S. population growth is much reduced.

The rapid growth of the Hispanic population in recent decades, fueled largely by immigration, has stimulated anxieties over its impact on the United States. One area of concern is Hispanic fertility, which seems to be persistently higher than among non-Hispanic whites and blacks, even across immigrant generations. Some have viewed the higher fertility of Hispanic women as potentially beneficial in some areas. Fertility levels are an important determinant of a population’s growth rate and age composition (Preston and Hartnett 2010), and there has long been recognition that very low fertility might not be a desirable demographic outcome. As such, the relatively higher fertility of Hispanic women could help mitigate population aging and the attendant financial pressures on the Social Security system (Jonsson and Rendall 2004; Sevak and Schmidt 2008). Far more commonly, however, Hispanic fertility is posed as a social problem. Many express concern that high Hispanic fertility, coupled with low average incomes, could perpetuate poverty and endanger the prospects for social mobility among Hispanic children. Moreover, the persistence of high fertility could reflect a larger failure of Hispanics to assimilate into the U.S. mainstream. And finally, if significantly higher fertility levels were to persist, Hispanics would comprise an ever larger share of the U.S. population in the future, even if Latin American immigration were to abruptly end. In tandem with the projected decline in the non-Hispanic white population over time, some have argued that these trends would alter the racial and ethnic order of the United States and contribute to social fragmentation across racial and ethnic lines (Huntington 2004).

Negative reactions to the fertility contribution of immigration to the U.S. population are not new and their long history can be traced back to the nineteenth-century. Nativist positions connected immigrants and their fertility to a myriad of social problems, including crime, poverty, and even mental health problems (King and Ruggles 1990). Similar concerns resonate today, with discussions of Hispanic fertility invariably linked, explicitly or implicitly, to concerns over racial change and the decline in the white majority. Like the Irish in the 19th century, Hispanic fertility today fuels an increased racialization of Hispanics as a distinctive group with allegedly identifiable physical and cultural traits that are at odds with the values that are assumed to define U.S. society (Santa Ana 2002; Cobas, Duany, and Feagin 2009).

In spite of the centrality of fertility to both demographic analyses, including population projections, and to heated rhetoric over the impact of immigration on the United States, our understanding of the actual level of Hispanic fertility remains poor. While a number of reports attempt to calculate the fertility of current generations of Hispanic women, they tend to neglect how the dynamics of migration shape fertility behavior, leading to distortions in fertility estimates for immigrant women that are so large as to overestimate the fertility of Hispanics as a whole (Parrado and Morgan, 2008; Parrado 2011). In this paper we follow a life-course perspective and systematically describe the connection between immigration and childbearing. We do so by combining original qualitative and quantitative data collected in Durham/Chapel Hill, NC with information from multiple national data sources. We use the qualitative information to document the main dimensions connecting migration and fertility and then measure their significance in quantitative analyses. The main argument is that while standard demographic methods tend to view migration and fertility as separate processes they are closely connected. Once the connection is taken into consideration the fertility levels of Hispanic women are much lower than those reported with standard measures, and the image of Hispanics as having unusually and persistently high fertility is unwarranted. Moreover, distinguishing between children born abroad and in the United States further limits Hispanics’ fertility-specific contribution to population growth.

Background: Hispanic fertility as a social problem Immigration, fertility, and the racialization of Hispanics

The Hispanic population of the U.S. grew dramatically in recent decades from 9.7 million or 4.7 percent of the total U.S. population in 1970, to 50.4 million or 16.3 percent of the U.S. population in 2010. While estimating the size of ethnic populations is not unproblematic,2 it is clear that the bulk of this growth has occurred via immigration. The Latin American born population of the United States doubled between 1960 and 1970 from 900,000 to 1.8 million. Between 1970 and 2009, the foreign born Hispanic population increased more than 10 times, reaching 18.1 million. Moreover, while in 1970 only 18 percent of all Hispanics were foreign born, today the proportion exceeds 37 percent. If we restrict our tabulations to adults (18 years of age and older), more than half (53 percent) of all Hispanics in the United States today were born in Latin America. Thus it is critical to recognize both the large share and recent arrival of the immigrant segment when assessing demographic outcomes among the U.S. Hispanic population.

Given their close association, it is perhaps not surprising that concern over Hispanic population growth and immigration are often linked. However, another important theme among those posing Hispanic population growth as a challenge to U.S. society is the purportedly high level of Hispanic fertility. Estimates of Hispanic fertility are considerably higher than among non-Hispanic whites and have remained so over time, helping to fuel a negative view of Hispanics and immigration. Together with their ‘foreign’ status, the reportedly high Hispanic fertility has become central to the racialization of Latin Americans as group that could undermine the foundation of the United States. As Cobas, Duany, and Feagin (2009) argue, racialization is a process of social construction that involves the definition of Hispanics as a distinct racial group and the denigration of their alleged physical and cultural characteristics, such as phenotype, language, or number of children.

It is not surprising that they stress the ‘number of children’ as a defining perception separating Hispanics as a “race.” In popular media representations the fertility of Hispanic women has consistently been portrayed in derogatory terms and as abnormally high. Even as far back as 1984, when the Hispanic population represented a mere 6.4 percent of the U.S. population, one could find alarmist media representations with titles such as “Hispanic fertility in U.S. found above norm” (New York Times, 1984). Less objective sources of information, particularly groups with anti-immigrant leanings, put Hispanic fertility in starkly negative terms. In a detailed content analysis of media representations of Hispanics, Chavez (2008) elaborates on what he calls the “Latino threat” narrative in reference to Latin American immigrants and their children. He documented the consistent popular representation of Hispanic women’s fertility as “dangerous,” “pathological,” “abnormal,” and even a threat to national security (p. 72). Gutiérrez (2008) documents that even in the social sciences research on the fertility of Hispanic women has long been entrenched under the presumption of cultural difference and inferiority. As related to their reproductive behavior, Hispanic (especially Mexican-origin) women were consistently “scientifically proven” to be significantly “deviant” from the purported “American ideal” despite considerable anomalies in reported statistics. She likewise showed that the historical construction of Hispanic women as hyper-fertile even contributed to the involuntary sterilization of Mexican-origin women in Los Angeles in the 1970s.

One of the most well-known and clearest articulations of the supposed dangers of high Hispanic fertility and population growth was made by Samuel Huntington, a renowned Harvard political science professor. He argued that immigration and high Hispanic fertility represent the “most immediate and most serious challenge to America’s traditional identity” (2004, p.32). This is so because Hispanics are different from prior immigrant groups and “the assimilation successes of the past are unlikely to be duplicated with the contemporary flood of immigrants from Latin America.” As a result the particular “blood and belief” identities that define America are being transformed. In his prediction, by ignoring the issue, “Americans acquiesce to their eventual transformation into two peoples with two cultures (Anglo and Hispanic) and two languages (English and Spanish)” (p.32). For Huntington, given these conditions, current “white nativism” should not be perceived as a threat that would lead to positions of white racial supremacy but a logical reaction to demographic trends by people who “believe in racial self-preservation and an affirm that culture is a product of race” (p. 41). Their main belief is that immigration and high fertility “foretell the replacement of white culture by black or brown cultures that are intellectually and morally inferior” (p. 41).

How high is Hispanic fertility?

Given the centrality of Hispanic fertility to a highly charged debate about the impact of Hispanic immigration on U.S. society, it is essential to evaluate the reliability of available estimates. The first step towards assessing reliability is a thorough understanding of the different measures used to capture fertility, and fertility differentials across groups (Bongaarts and Feeney 1998; Schoen 2004). The most straightforward measure of fertility is the Completed Fertility Rate (CFR), which asks women directly how many children they have borne. By the end of the reproductive period, usually at ages 40–44, it provides an accurate estimate of the total number of children that women bore over their lifetimes. While the CFR provides a very accurate gauge of fertility levels, it reflects past experiences, making it of little value for understanding the fertility of younger generations of women who still have many years of potential childbearing ahead of them.

For that reason, the most common measure for assessing current fertility levels is the Total Fertility Rate (TFR), which is an estimate of the number of children a woman would have if she were to experience the age-specific fertility rates observed in a particular period and survive from birth through the end of her reproductive life. TFR is computed by first calculating age-specific fertility rates (ASFRs) in a particular year which are obtained by dividing the number of births to women of a certain age by the total number of like-aged women in the population. ASFRs are then aggregated to produce the TFR. Formally, the TFR for year t can be written as:

where B(x,t) equals the number of births to women aged x at time t and N(x,t) is the number of women aged x at time t. The index of summation x ranges over all childbearing years. While TFR is commonly interpreted as an estimate of the average number of children a woman bears,3 in reality it is a hypothetical measure based on rates, and does not correspond to the actual behavior of any identifiable group or cohort. Rather, it relies on the age pattern of childbearing to provide an estimate of current fertility levels under the assumption that the age-specific rates in a given period will remain steady, and thus approximate the lifetime trajectories of actual birth cohorts.

Using this method of calculation, the fertility of Hispanic women indeed appears anomalously high. For 2008, the TFR calculated for Hispanic women was 2.9, which was more than one whole child higher than the level for non-Hispanic whites (1.8) and 0.8 child higher than the estimate for blacks (2.1) (Martin et al. 2010). Interpreting the TFR as the number of children women bear implies that more than half of Hispanic women have more than three children over their reproductive lives, with a substantial portion bearing four or five children. To put these figures in historical perspective, the TFR of Hispanic women today is only 0.6 children lower than the TFR estimated for white women (3.5) in 1960, at the peak of the baby-boom years. In fact, the TFR for Mexican immigrant women (3.1) is very close to that peak.

Moreover, TFR estimates indicate that Hispanic women’s fertility is not falling over time, as one would expect based on global population trends. In fact, the opposite appears to be the case. The TFR for Hispanics rose from 2.5 in 1980 to 3.0 in 1990, dipped to 2.6 in 1999, and then rose again to 3.0 in 2007 (CDC 2010; Martin et al. 2010). The increase was even more dramatic in certain states. In Georgia, Hispanic TFR was 2.3 in 1990 but increased to 3.5 in 2000, an increase of over one whole child. A similar trend is reported for North Carolina, the site of our study. Between 1990 and 2000 the TFR for Hispanics increased from 2.6 to 3.7 and Mexicans, in particular, were reported as having 4.4 children on average in 2000 (Sutton and Mathews 2006).4 The TFR for Mexican women in Georgia was likewise reported to be 4.5 children in 2000.

It is worth stressing that these TFR estimates of Hispanic fertility are indeed astoundingly high. They suggest that Hispanic fertility levels in the U.S. are both markedly higher than those registered in Mexico and Latin America and historically unprecedented. In 2000, for instance, TFR in Mexico was estimated to be 2.7 (Conapo 2011). Thus Mexican women in North Carolina were having an average of almost 2 more children than their counterparts in Mexico, which puts them more in line with fertility levels in sub-Saharan Africa. Given that decades of fertility research suggests that immigrant women usually average fertility levels that are between that of their host and home societies (Parrado and Morgan 2008), this is extremely anomalous. Moreover, trends in fertility have historically followed a nearly universal pattern: while there is considerable variation in the timing and pace of change and some fluctuations according to period conditions, once societies or cultures begin the process of moving from high- to lower-fertility regimes, there is no sustained return to high fertility. One salient exception was the baby boom that followed World War II and resulted from not only delayed childbearing during the war but also historic economic growth. And even that period of increased fertility did not last long or reach the level reported for Hispanics in some states.

Some have pointed to the pro-family vein in Hispanic culture to explain these highly anomalous patterns, while others have emphasized structural barriers to socioeconomic advancement that could maintain high fertility. But overall social scientists have been at a loss to explain why contemporary Hispanic fertility so starkly fails to conform to the experiences of countless other groups and historical periods. We argue that before constructing a cultural or even structural explanation for high Hispanic fertility, we should more critically examine the assumptions inherent in measures such as the TFR. More specifically, we argue that immigration is associated with significant changes in the timing of childbearing that violate the assumptions on which TFR is based, and dramatically overstate Hispanic fertility as a result. It has long been recognized that when childbearing ages are in flux, the TFR is a poor approximation of actual fertility behavior. For instance, in discussing the implications of the widespread use of fertility control for period fertility measures, Hajnal (1947) concluded that when women can time their fertility “a change in the rate at which people are having children in a given year can no longer be taken as an indication of a change in the number of children they will bear altogether in the course of their reproductive lives” (p. 143). Historical examples include the baby boom, when accelerated childbearing inflated period fertility estimates (Ryder 1983). It has also been argued that the extremely low fertility levels of several European countries today may be exaggerated due to delays in childbearing, since the ASFRs for earlier ages fall more than the actual reduction in fertility (Kohler, Billari, and Ortega, 2002). We argue that similar dynamics are at play when estimating contemporary Hispanic fertility in the United States. The age pattern of childbearing is strongly shaped by immigration, and the accordant distorting effects on TFR are likely to be sizeable. Moreover, lack of attention to the fact that the fertility of immigrant women often occurs in countries of origin undermines our understanding of the fertility-specific contribution of Hispanics to U.S. population growth.

Analytic strategy

Our study has two main objectives. The first is to illustrate the sources of bias in using TFR to estimate Hispanic fertility. In order to do so, the empirical analysis initially draws on qualitative data collected in Durham, NC to present a person-centered account of the link between migration and other life-course events, especially childbearing. We then use mathematical example to illustrate the impact of ignoring the connection between migration and childbearing for period fertility calculations. Finally, we use nationally representative data from the June supplement to the Current Population Survey (CPS) to compare estimates of fertility levels obtained from the TFR with the actual childbearing experience of women as estimated by the CFR. If we are correct that failure to account for migration-related disruptions in the timing of childbearing leads to artificially high estimates of Hispanic fertility, then we would expect TFR to exceed CFR for foreign-born but not native Hispanic women.

The second objective of our study is to distinguish between the fertility-specific contribution of immigrant women to the U.S. population and the immigration of their foreign-born children. That is, arguments over the contribution of Hispanic fertility to population growth often take the total number of children with immigrant parents as the fertility component. However, many of these children were born abroad and actually enter the country as immigrants. To illustrate the importance of this distinction, we calculate a modified version of the TFR that takes the timing of migration into consideration and estimates the number of children born in the U.S. We also present local level data from Durham, NC to illustrate that many children of immigrant women born abroad might never enter the United States at all.

Data

Data for the analysis come from two sources. The first source is the June Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS) for the years 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, and 2008. In addition to basic demographic information normally collected by the Census Bureau, the June Supplement also includes specific questions on both immigration and childbearing. Specifically, it contains information on the year of entry into the United States for immigrants, the total number of live births to date, and the year of birth of the last child. Together, the information allows for the calculation of both the TFR and CFR, separately by nativity. For immigrants, it also allows for the analysis of the relationship between migration and fertility timing. The data is restricted to women between the childbearing ages of 15 and 44.

While the CPS is a large-scale, nationally representative data source, it lacks much of the in-depth information needed to fully appreciate the interplay between immigration and family behavior. For instance, it is impossible to ascertain the connection between past fertility behavior or family separation and fertility after migration. We therefore supplement this analysis with both in-depth interviews and survey data collected as part of a mixed-methods study of the relationship between gender, immigration, and health risks among Hispanics in the Durham, NC area initiated in 2001 (Parrado, McQuiston, and Flippen, 2005). Durham represents an interesting setting for investigating the interaction between migration and fertility. The area has been growing rapidly, as part of the national shift in population from Rustbelt to Sunbelt states. The influx of highly educated workers attracted to growing job opportunities in the nearby Research Triangle Park, universities, and other large employers generated an intense demand for low-skill service and construction labor. As a result, the Hispanic population grew rapidly, from a mere 1 percent of the total population of Durham in 1990 to nearly 9 percent by 2000 and 11.9 percent by 2007, through both internal migration from more traditional immigrant gateways as well as direct migration from countries of origin (Flippen and Parrado 2011; Johnson-Webb 2003; Parrado, Flippen, and Uribe 2010). The Hispanic population of Durham is thus comprised mostly of recently arrived immigrants, and as noted above they register some of the highest (and most rapidly rising) fertility levels in the country, at least according to TFR estimates.

Our data collection strategy reflected the emerging nature of the Hispanic community, and employed a 3-pronged approach that relied on community-based participatory research (CBPR), targeted random sampling, and in-depth interviews and field research. CBPR uses a critical theoretical perspective that includes the “local theory” of community participants as collaborators in the research process (Israel et al. 2005). In our case, a group of 14 Hispanic men and women from the immigrant community were directly involved in every stage of the research. Monthly group meetings were held for more than 8 years to discuss research findings and gain culturally grounded interpretations of project findings. Early in the development of the project our CBPR meetings highlighted the close and complex connection between migration and fertility; we took these insights into explicit consideration when designing the survey questionnaire, which included detailed questions about the timing of migration and childbearing, as well as information about family separation and reunification.

The second main element of our research strategy was targeted random sampling. While the Hispanic population of Durham was growing rapidly, it was still not large or dispersed enough to warrant simple random sampling. Therefore, based on CBPR discussions and field work in the community we identified 35 different apartment complexes, street blocks, and trailer parks that housed large numbers of immigrant Hispanics and conducted targeted random sampling there. Specifically, we conducted a census of all the housing units in these 35 areas to construct a sampling frame and randomly selected individual units to be visited by interviewers. Any foreign born Hispanics (self-identified) between the ages of 18 and 49 qualified for interview, which was conducted in Spanish. Between 2006 and 2007 we conducted 787 surveys with immigrant women.

Finally, the third main element of our project was in-depth interviews and qualitative research. We purposively selected 22 women who had been interviewed for the survey, based on the rapport established with interviewers and the desire to represent the variation in female migration patterns. That is, we conducted nine interviews with women who migrated single, eight with women who migrated following their husbands, and five with women who migrated after marriage but without their husbands. We use the in-depth interviews to provide a person-centered approach to the life-course pathways connecting migration and fertility (Singer et al. 1998). Starting with rich, detailed information from individual narratives, the objective is to identify generalizable features affecting immigrant women that can then be extended to quantitative analyses.

Results

Person-centered accounts of the dynamics of migration and childbearing

Our main argument in this paper is that migration disrupts the timing of childbearing in such a way as to render the TFR an inaccurate measure of Hispanic immigrant fertility. Migration often involves spousal separation, which could result in childbearing delays. For women who migrate single, the favorable sex ratio could hasten union formation once in the United States, and childbearing often follows soon afterwards. The result is that women frequently initiate or complete their desired family size within a few years of migration, regardless of the age at which they migrate. This dynamic relationship between migration and fertility is not taken into consideration when calculating the TFR. Before presenting mathematical examples or comparisons of different measures of fertility by age, it is first instructive to take an in-depth, person-centered look at how migration shapes the timing of childbearing.

We begin with Maria and Antonio5, who were high school sweethearts in Puebla, Mexico and wanted to marry, but his job at the local tire factory was highly unstable and paid poorly. If they married they would not have been able to afford their own home, or even to furnish a rented apartment. So they decided Antonio would join his cousin in Durham, NC and work for a couple of years to save the money they would need to start their new life together. While his cousin helped him find work in construction right away, it was more difficult to save money than he had anticipated. There was little work in the winter and his mother had an unexpected illness in Mexico, both of which ate into their savings. Finally, after being apart for more than 4 years, he had saved enough to pay for Maria’s crossing and she joined him in Durham, at the age of 21. They married right away and had their first child a year and a half later, shortly after Maria had turned 23.

The Cruz sisters, Graciela, Natalia, Ines, and Dolores, illustrate the complexity in migration pathways that can exist even within a single family. The four women were born and raised in San Pedro, Guatemala, and their only brother, Carlos (the eldest sibling), was the first to leave for the United States. While he knew people in Texas and New York, an old friend who had settled in Durham, North Carolina told him of the ample jobs in construction there and offered him a place to stay. He had been living and working there for nearly 4 years when Graciela decided to migrate as well. Graciela, the eldest of the daughters, had formed a union and had her first child at the age of 20, and had a second child 2 years later with the same partner. When she was 32 she and the children’s father separated, and she found it very difficult to make ends meet financially. So she reluctantly decided to leave her children (then aged 10 and 12) in the care of her mother and join Carlos in Durham. Demand in construction was so high that she was able to find a job painting interiors for new housing developments and schools. While she initially found the work exhausting, and she missed her children dearly, she was able to send home enough money for both of them to attend private school. After living and casually dating for four years in Durham Graciela had an unintended pregnancy and gave birth to a baby girl at age 36, 4 years after having migrated to the United States. The father was an African American man with a small construction company for whom she had worked. While they did not marry, the father contributed financially and she was able to maintain her own separate household, and continue to send money to Honduras for her older children, who were now teenagers, to attend school. When her oldest turned 18, after she had been living in Durham for 6 years, he unexpectedly left school and headed north to join Graciela and his new sister in Durham.

Natalia took a very different migration/family path. Natalia was an elementary school teacher and unmarried in Honduras. While she enjoyed her job, the state often failed to pay teachers for months at a time and wage growth failed to keep pace with inflation. News of her sister’s earnings, and the ease of finding work in Durham, proved a strong incentive to migrate at the age of 24. Within a mere week of living in Durham Natalia had found a job as a nanny, taking care of 2 young children in their home. While she had migrated single, once in Durham, where the ratio of young men to young women is 2.3 to 1, it did not take Natalia long to meet a nice young man at church. They married a scant 9 months after her arrival in the U.S. Less than a year after marriage, roughly a year and a half after arriving in the U.S. at the age of 26, Natalia gave birth to a baby boy, Santiago. Santiago was not much of a sleeper, and proved a difficult toddler, so they were in no rush for a second. When they finally decided to try for a second child, 4 years later, Natalia had difficulty conceiving. It was not until 2 years after that, at the age of 32, that Natalia gave birth to her second and, according to her, last child.

The next to migrate was Ines. Ines had had her first child when she was just 17. She and the baby’s father never married, and they shared custody. Four years later, at the age of 21 she had a second child with a different partner. This father was less involved and offered no support for the baby. Finding it nearly impossible to support herself and her 2 children, Ines made the difficult decision to leave her four-year-old with his father and her 9-month-old baby with her mother (who was already caring for Graciela’s 2 teenage children) and join her siblings in Durham. She lived for nearly 6 months with Natalia and her husband, before moving in with a new boyfriend and his roommates. For the first few years she worked with Graciela painting houses, but eventually was able to find a less physically demanding job as a nanny to and African American nurse. While she missed her young sons dearly, she regretted having children so young and missing out on her care-free youth. In Durham she was determined to hang on to her freedom, while working as much as possible to send money back to her mother and youngest son. After 8 years in Durham, at the age of 30, she had not had any children in the United States.

Dolores, the youngest of the 5 Ramirez children, was the only one to remain in San Pedro, where she married and had 1 child at the time of this writing. According to her sisters, she had no plans to come to the United States, preferring to stay close to their aging mother.

One could go on recounting stories such as these indefinitely. While each story is unique in its own way, they all share compelling similarities. Most critically, in each case migration was closely tied to other life-course events, such as marriage, divorce, and childbearing. And in each case the act of migration shaped these other events. This introduces two important sources of complications for standard estimates of fertility. First, migration typically represents a marked disruption of family life. Before migration women might delay their childbearing, especially if the husband migrates to the U.S. alone. As women migrate they tend to reconstruct their lives within a few years after arrival. Many family behaviors, such as marriage and childbearing, tend to take place in a short period after migration irrespective of a woman’s age. As seen in the examples, women migrating at age 21 could be as likely to have a child 2 years after migration as women migrating at age 24 or even 32. This association could significantly shape the age pattern of childbearing without affecting the total number of children that women ultimately bear. This complex timing of events can distort fertility measures, such as the TFR, that are predicated on relatively stable age patterns of fertility behavior. Second, not all children of immigrants are born in the United States. In the Cruz family, for instance, of the seven children born to the three immigrant sisters, only 3 were born in the United States; an additional three remained in Guatemala, and one was in the United States, but entered through migration, not fertility.

The impact of migration-related timing disruptions on the TFR

While the qualitative interviews suggest that migration alters the timing of childbearing, they obviously cannot tell us how significant this disruption is or whether it is likely to have a substantial impact on estimates of Hispanic fertility level. To attempt to assess the magnitude of the disruption, we first draw on data from the CPS to systematically examine the relationship between migration and fertility timing. We document significant differences in the age pattern of childbearing between U.S.-born and immigrant Hispanic women. We then use a simple simulation to illustrate the potentially large impact of these age-patterned fertility levels for estimates of the TFR. Finally, we compare the applicability of the TFR for U.S. born and immigrant Hispanic women comparing TFR with CFR results that measure actual childbearing.

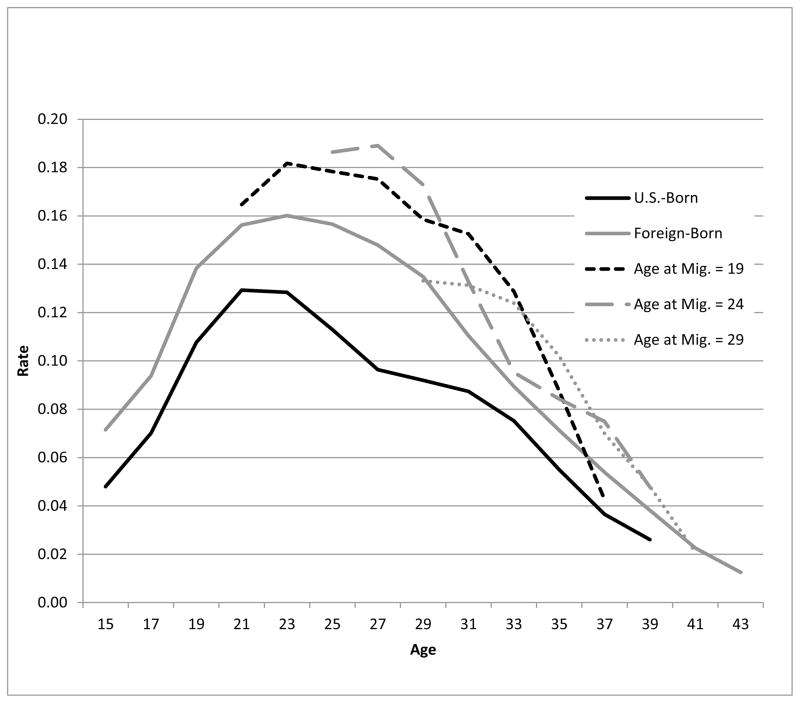

Figure 1 plots the ASFRs, the rates used to compute the TFR, for U.S.-born and immigrant Hispanic women. For immigrant women we also calculate and plot the U.S. ASFRs according to age at migration. If there is an association between migration and family formation, then we would expect the ASFR for immigrant women to be particularly high in the ages shortly after migration.6 Results indeed confirm these expectations. For native Hispanic women the figure shows an age pattern of childbearing that is common to many populations; the likelihood of having a child increases rapidly during the early 20s, and then declines sharply with age. There is a significantly smaller peak at around age 31, which likely reflects the childbearing of more highly educated women who postponed fertility until after their careers were more established. The ASFR curve for immigrant women, on the other hand, takes a very different shape. First, overall fertility levels are substantially higher among immigrants than natives at all ages. More importantly, fertility remains higher for immigrant women for a far longer period than was the case for native women. That is, while native women’s fertility peaks at 21 and remains at this level only for two years, for immigrant women fertility remains near the peak for eight or nine years before dropping off considerably. Thus, it would appear that immigrant women maintain high fertility rates for a far greater share of their reproductive lives, implying much higher completed fertility.

Figure 1. Age-specific fertility rates by nativity and age at migration.

Source: June Supplement, Current Population Surveys 2000–2008

However, the protracted period of high fertility among immigrant women does not hold when we disaggregate by age at arrival. For instance, among women migrating at age 19, ASFRs are indeed higher than those of native women, but they remain high for only three or four years before falling steeply. Among women migrating at age 24, the period of peak fertility is even shorter and falls off steeply after just one year. Women migrating at age 29 have lower U.S. fertility than their counterparts who came earlier, but also maintain high fertility levels for only a few years after migration. These patterns confirm the relevance of the in-depth qualitative life histories presented above; U.S. fertility among Hispanic immigrant women peaks in the years immediately following migration, irrespective of age of arrival. Women who migrate at young ages contribute to high ASFRs in their early 20s; women who migrate in their mid-twenties contribute to high ASFRs in their late twenties; and women who migrate in their late twenties contribute to high ASFRs into the early thirties. The main implication is that the higher observed ASFRs among immigrant women are mainly the product of new waves of women arriving to the U.S. and not sustained high fertility throughout the reproductive life.

The effects of these patterns for the calculation of the TFR are profound. A simple mathematical example illustrates the magnitude of the resulting overestimate of the level of Hispanic fertility. Let’s assume that a group of 100 women of different reproductive ages enters the United States in 2000. Each of these women had one child in Mexico and will ultimately bear only 2 children over their lifetimes. During the first year 15 percent of women in each age group has a second child and completes their fertility. Thus in the “reality” of this hypothetical example, by the end of the year 15 percent of the women will have two children and the remainder only one. Nevertheless, the ASFR in the United States in 2001 [f(x,t)] is a constant 15 percent. Following the formula for the TFR and adding over the reproductive years, the estimate for the year would be: TFR(2001) = Σ15–44(.15) = .15 * 30 years = 4.5. Using TFR would thus exaggerate these women’s completed fertility by 2.5 children, or 250 percent, since we stipulated that all women would ultimately bear only two children. Assuming that only 10 percent of women gave birth each year (but again would only eventually have two children) would produce a TFR of 3.0, which is close to the actual period estimate reported for immigrant Hispanic women. A constant rate of 11 percent would approximate the estimate for Mexican immigrants for the 2000–2008 period.

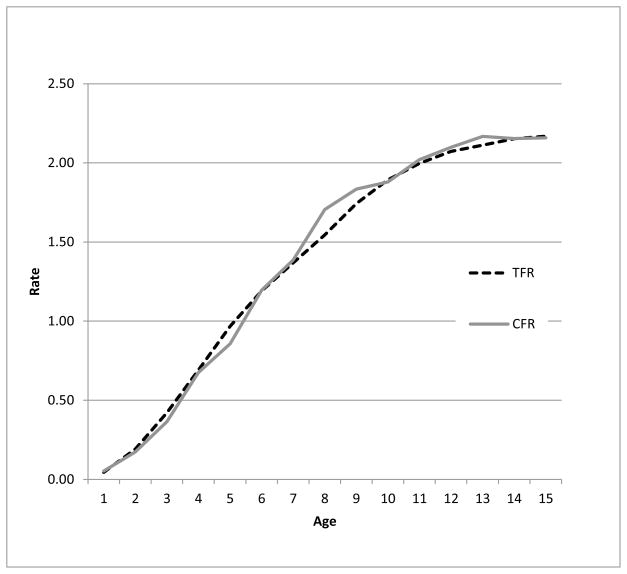

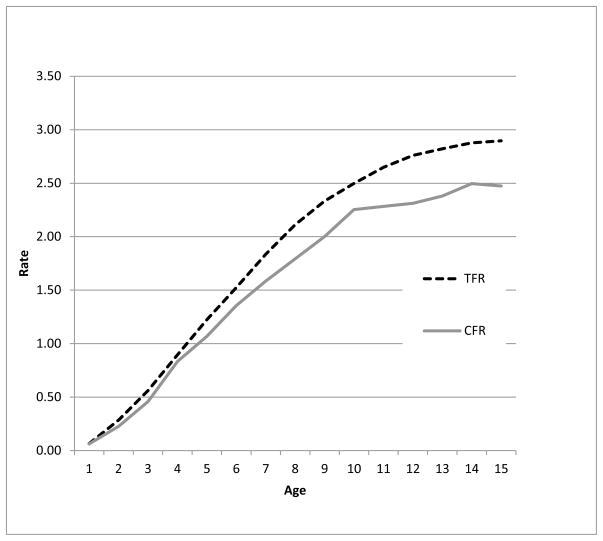

To further our case that the TFR is a poor estimate of fertility for immigrant women, Figures 2 and 3 compare CFR and TFR for foreign- and native-born Hispanic women using data from the 2000–2008 CPSs. Figure 2 show that the TFR and CFR overlap almost perfectly for U.S.-born Hispanic women. Both the period and the completed fertility estimates indicate that native-born Hispanics average 2.1 children per woman. For immigrant women, in contrast, Figure 3 shows that the CFR and TFR diverge dramatically. By age 44 the CFR is 2.5, compared to a TFR of 3.0. Thus the TFR overstates the level of immigrant fertility by 0.5 children, or 20 percent. Averaging the CFR of U.S. born and immigrant women at the end of their reproductive lives shows an average family size of 2.3, which is 0.6 children lower than the TFR estimate reported in NCHS reports.

Figure 2. TFR and CFR for US-Born Hispanic Women.

Source: Current Population Survey, June Supplement, 2000–2008

Figure 3. TFR and CFR for Foreign-Born Hispanic Women.

Source: Current Population Survey, June Supplement, 2000–2008

Thus, contrary to popular representations, Hispanic fertility is not out of control. Common estimates for Hispanics as a whole are inflated by the distorted figures produced by not properly accounting for timing issues among the foreign born. When we disaggregate by nativity, we see that native born Hispanic women do not maintain high fertility regardless of the measure of fertility used. In fact, the fertility level of U.S. born Hispanic women is at a ‘healthy,’ replacement level. For immigrant women, measures of completed fertility are higher than U.S.-born whites and Hispanics but not dramatically so. They are well below the fertility levels registered during the baby-boom years in the U.S. and lower than fertility levels in countries of origin. Moreover, given the continued fertility decline in Latin America, it is reasonable to speculate that fertility will continue to decline among younger cohorts of immigrant women.

Separating the fertility and immigration-specific contribution of the children of immigrant women

Alarmist representations imply not only that Hispanic fertility is abnormally high, but also that it comprises a growing share of Hispanic population growth in the United States. Indeed, a number of publications have noted that with the decline in immigration that has accompanied the 2007 economic recession, fertility is an increasingly important motor of Hispanic population growth. In tandem with the exaggerated estimates of Hispanic fertility, these analyses imply that even if immigration were to end, we would still have rapid Hispanic population growth due to fertility alone.

We argue that when assessing the importance of fertility to U.S. Hispanic population growth it is important to distinguish between children born in the United States and those born abroad. That is, we need to recognize that many immigrant women have children prior to migration. A large number of these children are raised in their countries of origin, and do not enter the United States at all. Moreover, even when the foreign-born children of immigrants do live in the United States, they enter the population equation through immigration, not fertility. Technically it is only U.S.-born children who represent the fertility-specific contribution of immigrant women to the U.S. population. Thus even CFR could over-estimate the impact of fertility on the size of the U.S. Hispanic population.

For instance, the CFR for immigrant women in Figure 3 is 2.5 children. However, the figure does not tell us where those children were born, or even if they are all residing in the United States. To get a sense for how much CFR overstates the fertility contribution of Hispanics to the U.S. population, we perform two separate analyses. First, we use CPS data to provide an estimate of the number of children that immigrant women bear in the United States alone and compare the results with the number of children ever born to assess how many births occur outside of the country. Second, since children born abroad may or may not enter the United States as immigrants, we next use data from the Durham project to assess the place of residence of immigrant women’s children.

To estimate the number of children born in the United States among immigrant women we rely on the computation of a U.S.-specific total fertility rate (USTFR). The USTFR is a modified version of the standard TFR that takes into account age at migration and time in the U.S. to avoid the problems arising from the disruption to the age pattern of childbearing resulting from migration. The USTFR is computed by first calculating time in the U.S.-specific fertility rates (USFRs) in a particular year for women migrating at a certain age. USFR are obtained by dividing the number of births among women with certain time in the U.S. by the total number of women with the same time in the U.S. in a particular age-at-migration cohort. USFRs are then aggregated to produce the USTFR for specific migration cohorts. Formally, the USTFR for year t for women who migrated at age a can be written:

where B(x,ta) equals the number of births to women with x time in the U.S. in year t and age at migration a. N(x,ta) is the number of women with x time in the U.S. in year t and age at migration a. The index of summation x ranges over the number of years in the U.S. Similar to the standard TFR, it is a hypothetical measure that treats the time in the U.S. specific rates in a given year for women who migrated at a certain age as if they characterize the lifetime trajectories of cohorts migrating at the same age. The actual childbearing experience of the age-at-migration cohorts is again given by the completed fertility rate (CFR(a)) that measures the average number of children that women migrating at a certain age a actually had by the end of their reproductive lives. Averaging the USTFR(ta) and the CFR(a) across all migrating ages results in the average period estimate of number of children that women have in the United States and the average number of children-ever-born, respectively. Subtracting USTFR(ta) from CFR(a) provides an estimate of the number of children that women had prior to U.S. migration.

Table 1 reports estimates of the USFRs, USTFR, and CFR by age at migration and time in the United States obtained from the CPS. Focusing on the USFR results show (as did Figure 1) that, regardless of age at migration, fertility levels are relatively high in the years shortly after migrating to the United States. Importantly though, in all cases the USFR declines very rapidly after women had approximated a CFR of two, which appears as the most common target family size. As a result, the USFR remains high for longer periods among women migrating between the ages of 15 and 19 since it takes them longer to reach a parity of two children. It is also higher for women migrating between the ages of 20 and 24, who have spent 7 to 8 years in the United States, than for women who migrated at ages 25 to29, since again, women migrating at younger ages more time in the United States to reach a parity of two.

Table 1.

U.S. specific fertility rates, total U.S. fertility rate, and completed fertility rate by age at migration

| AGE AT MIGRATION | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–19

|

20–24

|

25–29

|

||||||||||

| Years in U.S. | USFR | USTFR | CFR | Diff. | USFR | USTFR | CFR | Diff. | USFR | USTFR | CFR | Diff. |

| 1–2 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.36 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 1.25 | 1.01 |

| 3–4 | 0.17 | 0.66 | 0.79 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.75 | 1.31 | 0.56 | 0.15 | 0.53 | 1.57 | 1.04 |

| 5–6 | 0.22 | 1.09 | 1.13 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 1.13 | 1.51 | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.79 | 1.96 | 1.18 |

| 7–8 | 0.15 | 1.40 | 1.52 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 1.40 | 1.78 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.98 | 2.04 | 1.06 |

| 9–10 | 0.16 | 1.71 | 1.81 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 1.54 | 2.09 | 0.55 | 0.08 | 1.14 | 2.14 | 0.99 |

| 11–12 | 0.17 | 2.04 | 2.03 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 1.71 | 2.17 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 1.21 | 2.34 | 1.13 |

| 13–14 | 0.13 | 2.31 | 2.14 | −0.17 | 0.10 | 1.90 | 2.23 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 1.27 | 2.30 | 1.03 |

| 15–16 | 0.09 | 2.48 | 2.42 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 1.99 | 2.55 | 0.56 | ||||

| 17–18 | 0.04 | 2.57 | 2.67 | 0.11 | ||||||||

| 19–20 | 0.03 | 2.63 | 2.59 | −0.04 | ||||||||

| 30–34 | 35–39 | 40–44 | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Years in U.S. | USFR | USTFR | CFR | Diff. | USFR | USTFR | CFR | Diff. | USFR | USTFR | CFR | Diff. |

|

| ||||||||||||

| 1–2 | 0.11 | 0.23 | 1.76 | 1.54 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 2.31 | 2.22 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 2.54 | 2.47 |

| 3–4 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 2.14 | 1.85 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 2.12 | 1.98 | ||||

| 5–6 | 0.08 | 0.45 | 2.19 | 1.74 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 2.63 | 2.43 | ||||

| 7–8 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 1.87 | 1.33 | ||||||||

| 9–10 | 0.02 | 0.59 | 2.31 | 1.72 | ||||||||

Source: June Supplement, Current Population Surveys 2000–2008

The last row for each age-at-migration group provides an estimate of the U.S.-specific total fertility rate (USTFR) and the completed fertility in the United States (CFR) towards the end of women’s reproductive lives. Estimates for women migrating between the ages of 15 and 19 show the USTFR estimate to be 2.63, which is almost identical to the CFR estimate of 2.59. This implies, not surprisingly, that women who migrated at very young ages tend to have almost all of their children in the United States, rather than abroad. Differences between the two estimates grow as the age at migration increases. The difference between USTFR and CFR is 0.56 (2.55-1.99) for women migrating between the ages of 20 and 24; 1.03 (2.3-1.27) for women migrating between the ages of 25 and 29; 1.72 (2.31-0.59) for women migrating between the ages of 30 and 34. Women migrating at ages above 35 have for the most part completed their childbearing before migration and their fertility contribution in the U.S. is negligible. Results show that women migrating between 35 and 39 had a total of 2.63 children with only 0.20 born in the United States, and those migrating after age 40 averaged 2.54 children with only 0.07 born in the U.S. When we average across all age-at-migration groups we see that while Hispanic women average 2.5 children each (CFR(a)), less than half of them were born in the United States (1.13 U.S.-born vs. 1.36 born abroad prior to migration). Thus CFR over-states the fertility contribution of Hispanic immigrants by a wide margin.

Moreover, as the burgeoning literature on transnational families and our vignettes have highlighted, many children of immigrant women are raised by extended family members in their home communities and never join their parents in the United States. While this, too, undermines the utility of CFR as an indicator of the fertility component of Hispanic population growth, a lack of empirical data on the prevalence of the phenomenon limits our understanding of the magnitude of the problem. To address this issue we turn again to our data collected in Durham, NC, which not only asked information about total number of children ever born, but also the country of birth and place of current residence of all children.

Table 2 reports these results. In terms of fertility behavior, the local data documents a pattern consistent with the national level evidence obtained from the CPS above. Women who migrate at later ages tend to bear a greater share of their children in their countries of origin, rather than in the United States. For instance, women residing in Durham who migrated between the ages of 15 and 19 average only 0.2 children before migrating and 1.2 children in the United States, while women migrating over the age of 35 averaged 3.2 children at origin and only 0.1 children in the United States.

Table 2.

Place of birth and residence of Hispanic immigrant women’s children by age at migration

| All | Age at migration

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–19 | 20–24 | 25–29 | 30–34 | 35+ | ||

| Total children ever born | 1.95 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 3.3 |

| Children born in the U.S. | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| Children born at origin | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 3.2 |

| Number of Children born at origin currently in the U.S. | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.4 |

| Percent of Children born at origin currently in the U.S. | 46.6 | 56.3 | 53.3 | 43.3 | 46.0 | 45.0 |

| N | 740 | 206 | 225 | 154 | 83 | 72 |

Source: Gender, Migration, and HIV data set, collected 2006–2007 in Durham, NC

More importantly, a large share of immigrant women’s children who were born abroad were not living in the United States. In fact, our local estimates show that that less than half (46.6 percent) of the children born abroad to immigrant women had entered the United States by the time of survey. Moreover, results show that while the CFR for women in our sample was 1.95 at the time of interview, the total number of those children residing in the United States was only 1.4 (0.9 children born in the United States plus 0.5 children born abroad who later migrated), a full 23 percent lower than the number of children ever born. The pattern also varies considerably according to age at migration. Not surprisingly, the older women were at the time of migration the less likely they were to have brought their children to the United States; while 53.3 percent of women migrating in their early twenties (20–24) brought their foreign-born children to the United States, only 45 percent of women migrating over the age of 35 did so. Thus even ignoring the distinction between whether the children of Hispanic immigrants living in the United States were born here or abroad, CFR still over-estimates the fertility contribution of Hispanic immigration because many of the children born to immigrant women are not residing in the United States.

Conclusions and discussion

The perception that the fertility of Hispanic women is abnormally high is central to a highly charged debate on the impact of immigration on U.S. society. High Hispanic fertility is often framed not only as an impediment to the social mobility of Hispanic children, but is also an integral component of the racialization of Hispanics as a perpetually foreign group with cultural values and behaviors that are at odds with the American mainstream. In fact, commonly reported estimates that rely on the TFR as a measure of Hispanic fertility lend support to this perception. They indicate that the fertility of Hispanic women in the United States is indeed extremely high, with levels comparable to those reached in the United States during the baby-boom years and that even exceed those of women in Latin America. Moreover, they appear to increase, rather than decrease over time, in stark contrast to other groups. When used in population projections, along with the assumption of rigid racial boundaries between Hispanics and others, these fertility estimates fuel nativist fears of excessive Hispanic population growth and the decline of non-Hispanic white majority in the United States.

However, careful examination reveals considerable anomalies in reported estimates that raise concerns about the value of common demographic indicators. We argue that before elaborating on a cultural or even structural interpretation of the high level of Hispanic fertility it is important to critically evaluate the assumptions implicit in standard fertility measures and assess their applicability to Hispanics as a group. In this paper we demonstrate two main points. The first is that the assumptions embedded in the commonly reported TFR are not applicable to immigrant women and significantly inflate their fertility levels. Given the large share of immigrants among Hispanic women of reproductive ages, the problem distorts the level of fertility for all Hispanics as a group (Parrado 2011). The problem arises from well-known limitations embedded in relying on rates to assess the number of children that women will ultimately bear. As a measure of fertility level, the TFR assumes a stable age pattern of childbearing across birth cohorts. While this assumption holds well for native-born Hispanic women, among the foreign-born it does not, and the attendant distortion in the TFR is potentially sizeable.

Using both qualitative and quantitative information we documented that migration alters the age pattern of childbearing. Specifically, the act of immigration is a highly disruptive event that alters the timing of other life-course events, including childbearing. There is a strong tendency for women to have a birth within a few years after migrating to the United States, irrespective of the age at migration. This tendency raises the age-specific fertility rates used in the calculation of the TFR, artificially making it seem that Hispanic women maintain high rates of childbearing across a wider span of ages than is actually the case, thus inflating the TFR. This problem is particularly pronounced during periods of peak or increasing immigration, which helps explain why estimates of the TFR are even higher and rising more steeply in states where Hispanic entry is more recent (such as North Carolina, the site of our data collection).

To gauge the magnitude of this problem, we compared the number of children ever born (CFR) to the TFR for immigrant and native Hispanic women. For native Hispanic women both measures produce a similar estimate of Hispanic fertility as roughly 2.1 children per woman, on average. For immigrant women, on the other hand, the CFR (2.5) is 0.5 children (or 20 percent) lower than the TFR. In fact, this CFR is 17 percent lower than the TFR reported for all Hispanics, again indicating that over-estimates for immigrant women are so large as to distort the estimate for Hispanics as a whole. Even when native and immigrant women are considered together, the average number of children that Hispanic women bore by the end of their reproductive lives (ages 40–44) is 2.3. It is reasonable to assume that the number is lower among younger cohorts. Thus the characterization of Hispanic fertility as aberrantly high is unwarranted; native Hispanic women are at replacement level, which is considered healthy from the perspective of mitigating the effects of population aging. Immigrant women’s fertility is much lower than commonly reported, and below that of their countries of origin. There is every reason to expect that as fertility continues to fall in Latin America, it will likewise continue to fall among Latin American immigrants to the United States.

The second main point of the paper is that understanding the fertility-specific contribution of immigrant women to U.S. population growth requires explicit attention to the issue of where children were born and where they reside. Strictly speaking, the fertility-specific contribution of immigration to population growth is confined to children born in the United States. It is important to recognize that many women bear children prior to migration. A large share of those children remain in their countries of origin, and never become U.S. residents, and those that do join their parents in this country enter the population equation through immigration, not fertility. We document the importance of these distinctions by computing a U.S.-specific TFR that estimates the number of children born in the U.S. to a hypothetical cohort of immigrant women and compare the estimate to the actual number of children ever born. Results show that on average Hispanic immigrant women produce only half of their children in the United States, i.e. around one child. Moreover, evidence from Durham, NC indicates that less than half of the children born abroad were residing in the United States at the time of survey. The main implication is that even relying on the CFR, which we argue is superior to the TFR, exaggerates the fertility-specific contribution of Hispanic women to U.S. population growth by close to 25 percent. Thus the frequent assertion that fertility alone will propel the Hispanic population to an ever-greater share of the U.S. total, even in the absence of immigration, is untenable.

As with all research, it is important to note the limitations of this study. While measures of completed fertility are better suited for discussions surrounding family size, they are not particularly useful for studying the most recent wave of entrants into the United States due to their young ages and early stage of family formation. This renders it very difficult to answer some of the most pressing questions regarding the future growth of the Hispanic population, including how culture may shape behavior and whether Hispanic family behavior will differ from other groups. And, while in theory our argument applies equally well to any ethnic group with a large immigrant component, we have yet to test the relationship empirically for non-Hispanics. Our hypothesis is that the degree of the distortion in fertility estimates will vary in accordance with the relationship between migration and family formation behaviors and could be empirically tested by comparing different national origin groups. Similarly, future research could reexamine historical estimates of fertility levels among previous generations of European immigrants to the United States and assess the extent to which period and cohort measures aligned among historical immigrant populations.

It is also worth stating that we do not argue that the U.S. Hispanic population is not growing, nor do we dispute statistics showing that a growing share of U.S. children are of Hispanic origins. However, the meaning of these statistics is far from certain. Looking back historically at the shrill hysteria over Irish fertility at the turn of the 20th century, it is difficult to imagine that in 2009 the fact that 12 percent of the U.S. population identified Irish origins would be completely unremarkable. The commonly-reported projection that non-Hispanic whites will become a minority in the not-so-distant future suffers from the same fallacies that plagued nativist portrayals of the Irish. The fertility estimates on which they are partially based overstate the rate of growth of the Hispanic-origin population in the United States, and they presume a permanent racialization and stigmatization of Hispanics that may or may not come to pass. Regardless, given the inflammatory rhetoric surrounding Hispanic fertility today, special care must be taken to produce meaningful and reliable estimates. The challenge moving forward is to develop measures of demographic behavior that can account for the tight interplay between immigration and other life-course events. Such measures would allow us to better gauge the socioeconomic progress of immigrants and their descendants today rather than speculate about the meaning of long-term demographic projections of race and ethnicity.

Footnotes

“Hispanic” is a diverse category that includes many national origins and races. Roughly half of all Hispanics in the United States self-identify as white, and yet analyses typically include them in the non-white category when predicting racial and ethnic compositions over time, systematically “racializing” a diverse group.

To cite but two recent examples, in describing U.S. fertility differentials in 2001 a Population Reference Bureau (PRB) report reads: “With an average of more than three births per woman, the 2001 total fertility rate among Hispanics rivaled that of the U.S. population in the early 1960s during the tall end of the baby boom” (2003). Similarly, a 2006 PRB report imprecisely defines the TFR as “the average number of children a woman bears” (p. 3).

Hispanic immigration to North Carolina is a relatively new phenomenon, and immigrant women there average less than 7 years of U.S. residence. A TFR of 4.4 thus pushes the limits of credibility regarding the number of children women are biologically able to bear in such a short time period. We have shown in previous work that states with recent large increases in their immigrant populations are particularly prone to over-estimating Hispanic fertility, because the denominators used in calculating ASFRs are often seriously underestimated (Parrado 2011).

All names have been changed to protect the anonymity of research subjects.

The CPS does not contain birth history information that would allow us to follow cohorts of women and their fertility behavior before and after migration.

References

- Archibold Randal. New York Times. 2011. Aug 30, As refugees from Haiti linger, Dominicans’ good will fades. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J, Feeney G. On the Quantum and Tempo of Fertility. Population and Development Review. 1998;24:271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Health of the United States. 2010 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus.htm.

- Chavez Leo. The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation. Stanford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cobas José A, Duany Jorge, Feagin Joe R., editors. How the United States Racializes Latinos. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional de Poblacion, Mexico. Indicatores demográficos. 2011 http://www.conapo.gob.mx Consulted 9/19/2011.

- Flippen Chenoa A, Parrado Emilio A. The formation and evolution of Hispanic neighborhoods in new destinations: A case study of Durham, NC. City and Community. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6040.2011.01369.x. (forthcoming) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez Elena R. Fertility Matters: The Politics of Mexican-Origin Women’s Reproduction. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington Samuel. The Hispanic Challenge. Foreign Policy. 2004 Mar-Apr;:30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Webb Karen D. Recruiting Hispanic Labor: Immigrants in Non-traditional Areas. New York: LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson Stefan Hrafn, Rendall Michael S. The Fertility Contribution of Mexican Immigration to the United States. Demography. 2004;41(1):129–150. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King Miriam, Ruggles Steven. American immigration, fertility, and race suicide at the turn of the century. Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 1990;20:347–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler Hans-Peter, Billari Francesco, Ortega Jose. The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s. Population and Development Review. 2002;28:641–680. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports. 1. Vol. 59. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; Births: Final data for 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York Times. Hispanic fertility in US found above norm. 1984. Published December 18. [Google Scholar]

- Parrado Emilio A, McQuiston Chris, Flippen Chenoa. Participatory Survey Research: Integrating Community Collaboration and Quantitative Methods for the Study of Gender and HIV Risks among Hispanic Migrants. Sociological Methods and Research. 2005;34(2):204–239. [Google Scholar]

- Parrado Emilio A. How high is Hispanic fertility? Immigration and tempo considerations. Demography. 2011;48:1059–1080. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado Emilio A, Philip Morgan S. Intergenerational Fertility Patterns among Hispanic Women: New Evidence of Immigrant Assimilation. Demography. 2008;45(3):651–671. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Reference Bureau. US fertility rates higher among minorities. 2003 http://www.prb.org/Articles/2003/USFertilityRatesHigherAmongMinorities.aspx.

- Population Reference Bureau. Hispanics account for almost one-half of US population growth. 2006 http://www.prb.org/Articles/2006/HispanicsAccountforAlmostOneHalfofUSPopulationGrowth.aspx.

- Preseton Samuel, Hartnett Kristen. The future of American fertility. In: Shoven John., editor. Forthcoming in Demography and the Economy. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder Norman B. Cohort and period measures of changing fertility. In: Bulatao Rodolfo A, Lee Ronald D., editors. Determinants of fertility in developing countries. Vol. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 737–756. [Google Scholar]

- Santa Ana Otto. Brown Tide Rising. Methaphors of Latinos in Contemporary American Public Discourse. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sevak Pervi, Schmidt Lucie. Immigrant-Native Fertility and Mortality Differentials in the United States. Michigan Retirement Research Center, University of Michigan; P.O. Box 1248, Ann Arbor, MI 48104: 2008. WP2008–181. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen R. Timing Effects and the Interpretation of Period Fertility. Demography. 2004;41:801–819. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer Burton, Ryff Carol D, Carr Deborah, Magee William J. Linking life histories and mental health: A person-centered strategy. Sociological Methodology. 1998;28:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton PD, Mathews TJ. Birth and fertility rates by Hispanic origin subgroups: United States, 1990 and 2000. 57. Vol. 21. National Center for Health Statistics; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]