Abstract

Background

A number of investigators have evaluated the association between the ABCB1 polymorphism and clopidogrel responding, but the results have been inconclusive. To examine the risk of high platelet activity and poor clinical outcomes associated with the ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism in CAD patients on clopidogrel, all available studies were included in the present meta-analysis.

Methods

We performed a systematic search of PubMed, Scopus and the Cochrane library database for eligible studies. Articles meeting the inclusion criteria were comprehensively reviewed, and the available data were accumulated by the meta-analysis.

Results

It was demonstrated that the ABCB1 C3435T variation was associated with the risk of early major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (T vs. C OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.62; P = 0.003; TT vs. CC: OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.19 to 2.63; P = 0.005; CT + TT vs.CC: OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.06 to 2.06; P = 0.02) and the polymorphism was also associated with the risk of the long-term MACE in patients on clopidogrel LD 300 mg (T vs. C: OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.48; P = 0.001; TT vs. CC: OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.19 to 2.13; P = 0.002; CT + TT vs.CC: OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.79; P = 0.01). The comparison of TT vs. CC was associated with a reduction in the outcome of bleeding (TT vs. CC: OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.66; P<0.00001). However, the association between ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and platelet activity and other risk of poor clinical outcomes was not significant.

Conclusions

The evidence from our meta-analysis indicated that the ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism might be a risk factor for the MACE in patients on clopidogrel LD 300 mg, and that TT homozygotes decreased the outcome of bleeding compared with CC homozygotes.

Introduction

Clopidogrel inhibits the adenosine-diphosphate-induced platelet aggregation, reducing the cardiovascular complications in patients with coronary atherosclerotic heart disease (CAD), especially in those undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [1]. However, the pharmacodynamic response to clopidogrel varies greatly among patients [2], and patients with lesser degrees of platelet inhibition are more likely to experience recurrent ischemic events [3], [4]. Although the mechanisms have not been fully clarified, genetic polymorphisms may play a vital role in individual susceptibility to drug response [5].

The ABCB1 (ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B, member 1, also called MDR1 or TAP1) gene encodes the intestinal efflux transporter P-glycoprotein, which modulates the absorption of clopidogrel [6]. The ABCB1 gene locates at 7, p21–21.1 [7], and more than 50 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) within this gene have been described in the literature. Among them, the ABCB1 C3435T (rs1045642) is extensively studied and some research has been shown that the ABCB1 C3435T genotype influences the impaired function of P-glycoprotein which can hinder the absorption of clopidogrel [8].

Antiplatelet response could be investigated through poor clinical outcomes and impaired response to antiplatelet therapy in the laboratory test. Simon et al. [9] first analyzed the effect of C3435T polymorphism on clinical outcomes in patients receiving clopidogrel and found that patients with TT genotype had a higher rate of subsequent cardiovascular events than those with CC genotype. One study [10] indicated that the ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism influenced ADP dependent platelet reactivity and showed that T-allele carriers were likely to have a poor response to antiplatelet therapy in the lab test. However, the results from different studies [9]–[20] were inconsistent. Thus, in the present study, a meta-analysis was performed to delineate the association between ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and platelet activity as well as the risk of poor clinical outcomes in patients treated with clopidogrel.

Methods

1. Literature Search

Three electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus and the Cochrane library) were searched (the last search was updated in March 2012 with the following terms combined: antiplatelet, clopidogrel, aspirin, platelet activity, ABCB1, MDR1, multidrug resistance, polymorphism). All eligible studies were retrieved and their bibliographies as well as the previous meta-analysis were checked for other relevant studies.

2. Inclusion Criteria

The studies that met the following criteria were included: (1) published in English, (2) case- control studies on platelet activity and prospective cohort studies on clinical outcomes, (3) the evaluation of the ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism, platelet activity and the poor clinical outcomes in patients receiving clopidogrel, (4) availability of the genotype frequency on target population, and (5) the valid date, on publication or through corresponding by e-mail, to work out an odds ratio (OR) or P-value with 95% confidence interval (CI).

3. Data Extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted the data and reached a consensus on all items. The following information was achieved from each study: the first author’s name, publication date, ethnicity, population studied, characteristic of target population, treatment protocal,definition of cases, poor outcomes, study period and gene information, respectively.

4. Study Outcomes

The two parts of endpoints (high platelet activity and poor clinical outcomes) were studied. The poor clinical outcomes included major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) which were composed of cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, as well as all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, definite or probable stent thrombosis and major or minor bleeding.

5. Statistical Analysis

The observed genotype frequencies in controls or entire cohorts were tested to compare with the expected genotype frequencies by Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). Crude odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) in each study was used to assess the strength of association between ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and platelet activity as well as the poor clinical outcomes in patients who received clopidogrel. According to the method described by Woolf [21], the pooled ORs were assessed for allele comparison (T vs. C), dominant genetic model (CT + TT vs.CC), recessive genetic model (TT vs. CC + CT) and homozygote comparison (TT vs. CC), and its significance was evaluated by the Z-test. Heterogeneity between studies was diagnosed by the use of the χ2 - based Q statistic test, and regarded as significant if p value was less than 0.1 [22]. Meanwhile the statistic of I2 was used to efficiently test for the heterogeneity, with I2 less than 25%, 25–50%, and greater than 50% as low, moderate and high degree of inconsistency, respectively [23]. The fixed-effect method was adopted if the effects were appeared to be homogeneous, or the random-effect model was conducted.

Subgroup analyses were applied to identify the heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by sequential omission of individual studies respectively to detect the potential influence of each study set to the pooled ORs. In addition, publication bias was carried out by the funnel plot, and the symmetry of the plot distribution indicated the absence of publication bias [24]. Funnel-plot asymmetry was assessed with the Begg’s [25] and Egger’s [26] tests. All statistical tests were performed with the Stata (v.10.0, Stata Corporation) and Review Manager (v.5.1, The Cochrane Collaboration), and were considered significant if the 2-sided P value was less than 0.05.

Results

1. Study Characteristics

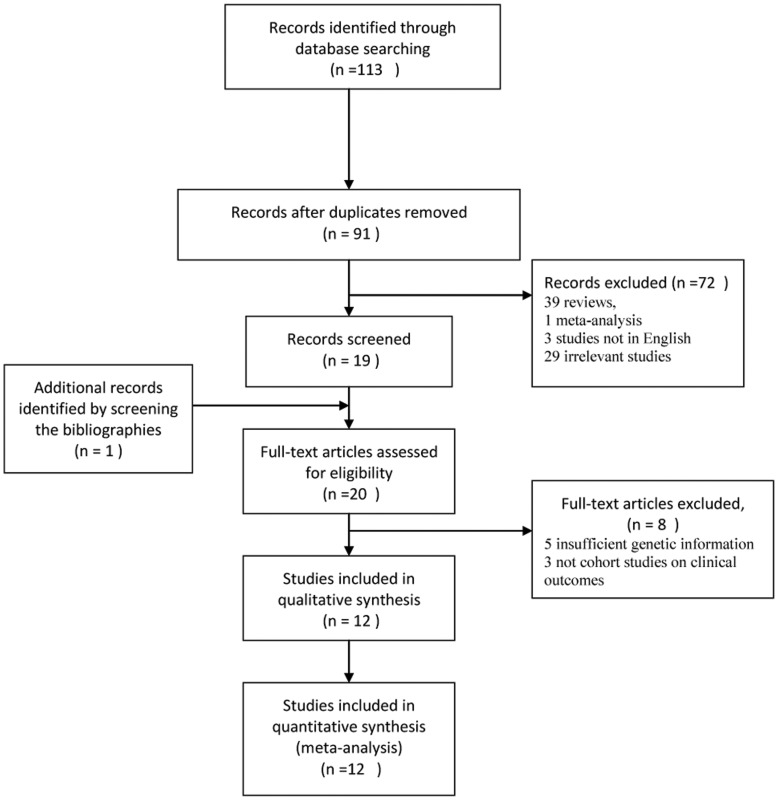

A total of 113 studies on the ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism with respect to platelet activity and the poor clinical outcomes were found, of which 22 replicated studies were excluded. Additionally, 39 reviews, 1 meta-analysis and 3 studies not in English were excluded. Meanwhile, 29 irrelevant studies were excluded by reviewing the title and abstract and one trial [27] was identified by screening the bibliographies. And then, five studies [28]–[32] were excluded due to their insufficient genetic information, and three trials [27], [33], [34] on clinical outcomes were excluded because they were not cohort studies. The result on platelet activity test from Wang [11] was so suspicious that we excluded it from current meta-analysis on the polymorphism and the degree of platelet inhibition by test. Finally, twelve studies, of which four involved platelet activity and ten involved clinical outcomes, met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1), and the main characteristics of them were summarized in Tables 1, 2 and 3. Various genotyping methods were applied including allele-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [10], [11], Taqman Assays[12]–[14], [16]–[20], Affymetrix Assay and Illumina Infinium Beadchip Assay [15], as well as SNPlex [9]. Distribution of genotypes in the controls or the total of each cohort (Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10) were all not deviated from HWE.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the trial selection process.

Table 1. Main characteristics of studies included on platelet activity tests in the meta-analysis.

| First author | year | ethnicity | population studied | treatment protocal | definition of case | case | control | HWE | ||||

| CC | CT | TT | CC | CT | TT | |||||||

| Spiewak, M. [10] | 2009 | NA | ACS treated with PCI | LD aspirin 300 mg clopidogrel (300 mg or 600 mg)MD aspirin 75 mg clopidogrel 75 mg qd | collagen/adenosine diphosphate (CADP)-CT<130s | 4 | 16 | 10 | 23 | 34 | 11 | 0.791 |

| Kim, I. S. [12] | 2012 | Asian | Patients treated with PCI | cilostazol 100 mg bid, clopidogrel 75 mg and aspirin 200 mg qd | 5 mol/l ADP-induced maximal PR (Aggmax)>46%. | 7 | 4 | 1 | 45 | 58 | 12 | 0.287 |

| Jeong, Y. H. [13] | 2010 | Asian | AMI treated with coron ary angiography or PCI | MD clopidogrel 150 mg aspirin 200 mg qd | 5 mol/l ADP-induced maximal PR (PRmax)>50%. | 13 | 14a | 56b | 55b | 15b | 0.791 | |

| Jeong, Y.H. [14] | 2011 | Asian | AMI treated with PCI | LD aspirin 300 mg clopidogrel 600 mgMD aspirin 100–200 mg clopidogrel 75 mg | 20 mol/L ADP-induced maximal PR(PRmax)>59% | 64 | 54 | 16 | 60 | 54 | 18 | 0.303 |

LD: loading dose; MD: maintenance dose; HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

the number is consisted of CT and TT.

the number is consisted of case group and control group.

Table 2. Main characteristics and genotype of studies included on the poor clinical outcomes in the meta-analysis.

| First author | Year | ethnicity | Male gender,No. (%) | Hypertension, No. (%) | Diabetes,No. (%) | Hypercholester-olemia No. (%) | Previous or current smoker, No. (%) | Total | HWE | ||

| CC | CT | TT | |||||||||

| Mega, J. L. [15] | 2010 | Caucasian(97.6) | 1040(70.7) | 1903(64.9) | 321(21.8) | 1424(48.6) | 560(38.1) | 330 | 727 | 414 | 0.750 |

| Simon, T. [9] | 2009 | NA | 1559(70.6) | 1280(58.0) | 698(31.6) | 1088(49.3) | 1206(54.6) | 564 | 1050 | 574 | 0.060 |

| Spiewak, M. [10] | 2009 | NA | 69(70.4) | 52 (53.1) | 17(17.3) | 35 (35.7) | 43 (43.9) | 26 | 44 | 18 | 0.938 |

| Wallentin, L. [16] | 2010 | Caucasian (98) | 3571 (69.0) | NA | 1189 (23) | NA | 3099(60.2) | 1195 | 2518 | 1386 | 0.434 |

| Tiroch, K. A. [17] | 2010 | NA | 694(74.8) | 691(74) | 224(24.1) | 482(52) | 339(36.5) | 203 | 457 | 268 | 0.755 |

| Campo, G. [18] | 2011 | NA | 231(77) | 215 (72) | 71(23.7) | 153 (51) | 71(23.7) | 69 | 157 | 74 | 0.416 |

| Delaney, J. T. [19] | 2012 | Caucasian | 440(63.5) | 560(80.8) | 241(34.8) | 643(92.8) | 419(60.5) | 173 | 336 | 179 | 0.543 |

| Wang, X. D. [11] | 2012 | Asian | 361(67.4) | 305(56.9) | 273(50.9) | 295(55.0) | 186(34.7) | 364 | 161 | 11 | 0.478 |

| Jeong, Y. H. [14] | 2011 | Asians | 195 (73.3) | 125 (47.0) | 70 (26.3) | 71 (26.7) | 141 (53.0) | 124 | 108 | 34 | 0.216 |

| Jaitner, J. [20] | 2012 | Caucasian | 1180(77.4) | 1362(89.4) | 430(28.2) | 1068(70.1) | 207(13.6) | 444 | 740 | 340 | 0.342 |

NA, not applicable.

Table 3. Treatment characteristics of studies included on the poor clinical outcomes in the meta-analysis.

| First author | Year | Population studied | Treatment protocal | Study period | The poor outcomes |

| Mega, J. L. | 2010 | ACS treated with PCI | LD clopidogrel 300 mg | 15 months | stent thrombosis |

| MD clopidogrel 75 mg qd | major or minor bleeding | ||||

| MACE (cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction and non-fatal stroke) | |||||

| Simon, T. | 2009 | AMI treated withcoronary angiography or PCI | LD clopidogrel 300 mg aspirin(98%) | 12 months | outcome event (Death,nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke) |

| Spiewak, M | 2009 | ACS treated with PCI | LD aspirin 300 mg clopidogrel(300 mg or 600 mg) | 1.7 years | cardiovascular deaths and non-fatal myocardial infarction |

| MD aspirin 75 mg clopidogrel75 mg qd | |||||

| Wallentin, L. | 2010 | Acute coronarysyndrome. | LD clopidogrel 300–600 mg, | 12 months | Cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke, |

| MD clopidogrel 75 mg qd aspirin (96%) | Definite stent thrombosis | ||||

| Major bleeding | |||||

| Tiroch, K. A. | 2010 | AMI treated withcoronary angiography | LD clopidogrel 600 mg | 12 months | MACE(including death, MI, TLR, and stroke) |

| MD aspirin 100 mg bid clopidogrel 75 mg qd | Stent thrombosis | ||||

| Campo, G. | 2011 | Ischemic heart disease underwent PCI | LD aspirin 300 mg clopidogrel 600 mg | 12 months | Ischemic adverse events(Death, MI, stroke, stent thrombosis) |

| MD aspirin 300 mg clopidogrel75 mg qd | minor or major bleedings | ||||

| Delaney, J. T. | 2012 | MI or treated with PCI | Clopidogrel not applicable | 12–24 months | Primary endpoint cardiovascular events(all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, revascularization, and stent thrombosis) |

| Wang, X. D. | 2012 | Patients treatedwith PCI | LD aspirin 100 mg clopidogrel 300 mg | 1 month | Major or Minor bleeding |

| MD aspirin 100 mg clopidogrel75 mg qd | Early definite stent thrombosis | ||||

| MACE(included cardiovascular death, stent thrombosis, recurrent acute coronary syndrome) | |||||

| Jeong, Y. H. | 2011 | AMI treated withcoronary angiography or PCI | LD aspirin 300 mg clopidogrel 600 mg | 12 months | major or minor bleeding |

| MD aspirin 100–200 mg clopidogrel 75 mg qd | MACE (cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and ischemic stroke) | ||||

| Jaitner, J. | 2012 | Patients treatedwith PCI | LD aspirin 500 mg clopidogrel 600 mg | 14 months | stent thrombosis |

| MD Aspirin 100 mg bid, clopidogrel 75 mg bid*3d then 75 mg qd |

LD: loading dose; MD: maintenance dose; HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Table 4. The distribution of ABCB1 C3435T genotypes for patients with and without long-term MACE.

| T | C | TT | CC | TT | CT+CC | TT+CT | CC | |||||||||

| first author | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total |

| Wallentin 2010 [16] | 507 | 5290 | 509 | 4908 | 137 | 1386 | 138 | 1195 | 137 | 1386 | 371 | 3713 | 370 | 3904 | 138 | 1195 |

| Simon 2009 [9] | 318 | 2198 | 262 | 2178 | 85 | 574 | 57 | 564 | 85 | 574 | 205 | 1614 | 233 | 1624 | 57 | 564 |

| Mega 2010 [15] | 158 | 1555 | 106 | 1387 | 52 | 414 | 26 | 330 | 52 | 414 | 80 | 1057 | 106 | 1141 | 26 | 330 |

| Campo 2011 [18] | 28 | 305 | 14 | 226 | 8 | 74 | 1 | 69 | 8 | 74 | 13 | 226 | 20 | 231 | 1 | 69 |

| Tiroch 2010 [17] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 22 | 725 | 63 | 203 |

| Spiewak 2009 [10] | 12 | 80 | 8 | 96 | 3 | 18 | 1 | 26 | 3 | 18 | 7 | 70 | 9 | 62 | 1 | 26 |

| Jeong 2011 [14] | 7 | 176 | 19 | 356 | 1 | 34 | 7 | 124 | 1 | 34 | 12 | 232 | 6 | 142 | 7 | 124 |

Table 5. The distribution of ABCB1 C3435T genotypes for patients with and without early MACE.

| first author | T | C | TT | CC | TT | CT+CC | TT+CT | CC | ||||||||

| event | Total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | |

| Simon 2009 [9] | 160 | 2198 | 128 | 2178 | 41 | 574 | 25 | 564 | 574 | 41 | 1614 | 103 | 1624 | 119 | 564 | 25 |

| Mega 2010 [15] | 102 | 1555 | 62 | 1387 | 35 | 414 | 15 | 330 | 414 | 35 | 1057 | 47 | 1141 | 67 | 330 | 15 |

| Wang 2012 [11] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 172 | 5 | 364 | 15 |

Table 6. The distribution of ABCB1 C3435T genotypes for patients with and without MI.

| first author | T | C | TT | CC | TT | CT+CC | TT+CT | CC | |||||||||||

| event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | ||||

| Mega 2010 [15] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 48 | 414 | 70 | 1057 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Campo 2011 [18] | 18 | 305 | 8 | 295 | 5 | 74 | 0 | 69 | 5 | 74 | 8 | 226 | 13 | 231 | 0 | 69 | |||

| Tiroch 2010 [17] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 16 | 725 | 6 | 203 | |||

| Wang 2012 [11] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 172 | 7 | 364 | |||

| Delaney 2012 [19] | 33 | 694 | 43 | 682 | 6 | 179 | 11 | 173 | 6 | 179 | 32 | 509 | 27 | 515 | 11 | 173 | |||

Table 7. The distribution of ABCB1 C3435T genotypes for patients with and without stroke.

| first author | T | C | TT | CC | TT | CT+CC | TT+CT | CC | ||||||||

| event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | |

| Wallentin 2010 [16] | 41 | 5290 | 35 | 4908 | 13 | 1386 | 10 | 1195 | 13 | 1386 | 25 | 3713 | 28 | 3904 | 10 | 1195 |

| Mega 2010 [15] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 414 | 3 | 1057 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Campo 2011 [18] | 2 | 305 | 2 | 295 | 1 | 74 | 1 | 69 | 1 | 74 | 1 | 226 | 1 | 231 | 1 | 69 |

| Tiroch 2010 [17] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 725 | 1 | 203 |

| Delaney 2012 [19] | 1 | 694 | 1 | 682 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 179 | 1 | 509 | 1 | 515 | 0 | 173 |

Table 8. The distribution of ABCB1 C3435T genotypes for patients with and without mortality.

| first author | T | C | TT | CC | TT | CT+CC | CT+TT | CC | ||||||||

| event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | |

| Mega 2010 [15] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5 | 414 | 8 | 1057 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Campo 2011 [18] | 8 | 305 | 4 | 295 | 2 | 74 | 0 | 69 | 2 | 74 | 4 | 226 | 6 | 221 | 0 | 69 |

| Tiroch 2010 [17] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 47 | 725 | 17 | 203 |

| Delaney 2012 [19] | 12 | 694 | 16 | 682 | 4 | 179 | 6 | 173 | 4 | 179 | 10 | 509 | 8 | 515 | 6 | 173 |

Table 9. The distribution of ABCB1 C3435T genotypes for patients with and without thrombosis.

| first author | T | C | TT | CC | TT | CT+CC | TT+CT | CC | ||||||||

| event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | |

| Wallentin2010 [16] | 56 | 3487 | 62 | 3239 | 14 | 917 | 17 | 793 | 14 | 917 | 45 | 2446 | 42 | 2570 | 17 | 793 |

| Mega 2010 [15] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5 | 392 | 12 | 1004 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Campo 2011 [18] | 6 | 305 | 2 | 295 | 2 | 74 | 0 | 69 | 2 | 74 | 2 | 226 | 4 | 231 | 0 | 69 |

| Tiroch 2010 [17] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 725 | 3 | 203 |

| Wang 2012 [11] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 172 | 5 | 364 |

| Delaney 2012 [19] | 7 | 694 | 15 | 682 | 1 | 179 | 5 | 173 | 1 | 179 | 10 | 509 | 6 | 515 | 5 | 173 |

| Jaitner 2012 [20] | 69 | 1420 | 63 | 1628 | 19 | 340 | 16 | 444 | 19 | 340 | 47 | 1184 | 50 | 1080 | 16 | 444 |

Table 10. The distribution of ABCB1 C3435T genotypes for patients with and without bleeding.

| first author | T | C | TT | CC | TT | CT+CC | TT+CT | CC | ||||||||

| event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | event | total | |

| Wallentin 2010 [16] | 519 | 5272 | 477 | 4884 | 137 | 2508 | 116 | 1188 | 137 | 1382 | 361 | 3696 | 382 | 3890 | 116 | 1188 |

| Mega 2010 [15] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15 | 414 | 26 | 1052 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Campo 2011 [18] | 16 | 305 | 22 | 335 | 4 | 157 | 7 | 69 | 4 | 74 | 15 | 226 | 12 | 231 | 7 | 69 |

| Jeong 2011 [14] | 5 | 176 | 11 | 356 | 1 | 108 | 4 | 124 | 1 | 34 | 7 | 232 | 4 | 142 | 4 | 124 |

| Wang 2012 [11] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 10 | 172 | 20 | 364 |

NA, not applicable.

2. Meta-analysis Results

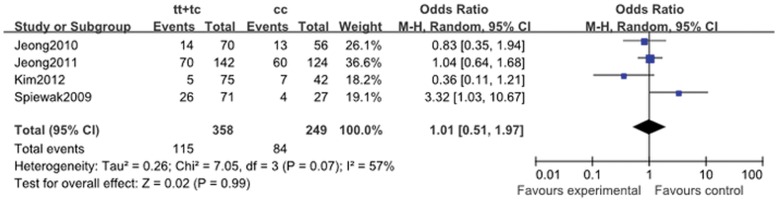

2.1. Platelet activity

When four eligible studies were pooled, the association between platelet high activity and the ABCB1 C3435T variation was not significant (for CT + TT vs.CC: OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.451 to 1.97; P = 0.99; Fig. 2). The heterogeneity existed in allele comparison (I2 = 74%; P = 0.02), homozygote comparison (I2 = 67%; P = 0.05) and dominant genetic model (I2 = 57%; P = 0.07) (Table 11).

Figure 2. Pooled random-effects-based odds ratio of platelet activity associated with ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism.

Comparison: TT+TC vs. CC.

Table 11. The total and stratified analysis of the ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism on antiplatelet responding.

| T vs. C | TT vs. CC | TT vs. CC + CT | CT + TT vs.CC | |||||||||

| Variables | OR(95%CI) | P a | P | OR(95%CI) | P a | P | OR(95%CI) | P a | P | OR(95%CI) | P a | P |

| Platelet activity | 1.06 (0.53, 2.13) | 0.02 | 0.86 | 1.36 (0.35, 5.30) | 0.05 | 0.66 | 1.20 (0.69, 2.08) | 0.19 | 0.53 | 1.01 (0.51, 1.97) | 0.07 | 0.99 |

| MACE | 1.16 (0.94, 1.45) | 0.01 | 0.17 | 1.39 (0.86, 2.24) | 0.007 | 0.18 | 1.26 (0.98, 1.63) | 0.01 | 0.08 | 1.09 (0.77, 1.54) | 0.008 | 0.62 |

| LD 600 mg | 1.13 (0.55, 2.29) | 0.19 | 0.74 | 2.05 (0.13, 31.97) | 0.07 | 0.61 | 1.48 (0.51, 4.29) | 0.27 | 0.47 | 1.06 (0.43, 2.64) | 0.12 | 0.09 |

| LD 300 mg | 1.28 (1.10, 1.48) | 0.53 | 0.001 | 1.59 (1.19, 2.13) | 0.79 | 0.002 | 1.42 (0.98, 2.06) | 0.01 | 0.07 | 1.39 (1.08, 1.79) | 0.43 | 0.01 |

| others | 1.09 (0.61, 1.93) | 0.16 | 0.78 | 1.24 (0.32, 4.88) | 0.17 | 0.76 | 1.00 (0.81, 1.22) | 0.48 | 0.99 | 1.20 (0.32, 4.56) | 0.15 | 0.79 |

| MACE early | 1.34 (1.10, 1.62) | 0.39 | 0.003 | 1.77 (1.19, 2.63) | 0.70 | 0.005 | 1.47 (0.85, 2.56) | 0.06 | 0.17 | 1.48 (1.06, 2.06) | 0.48 | 0.02 |

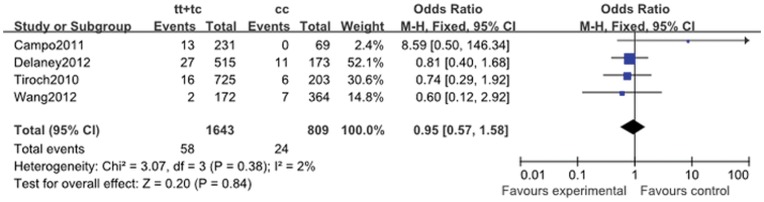

| MI | 0.81 (0.55, 1.18) | 0.53 | 0.27 | 1.78 (0.08, 39.04) | 0.04 | 0.72 | 1.26 (0.54, 2.93) | 0.03 | 0.59 | 0.95 (0.57, 1.58) | 0.38 | 0.84 |

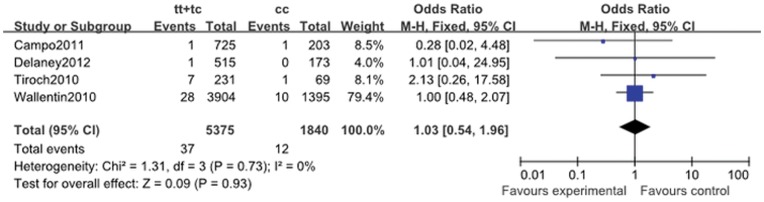

| Stroke | 1.08 (0.70, 1.67) | 0.99 | 0.73 | 1.11 (0.50, 2.44) | 0.90 | 0.8 | 1.46 (0.80, 2.66) | 0.94 | 0.22 | 1.03 (0.54, 1.96) | 0.73 | 0.93 |

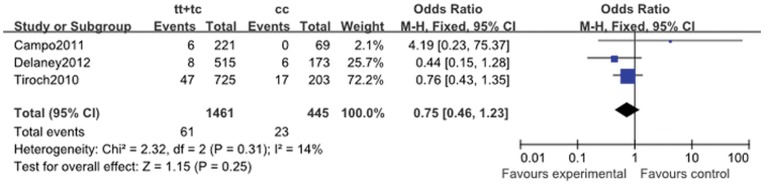

| All-cause mortality | 0.98 (0.52, 1.83) | 0.18 | 0.94 | 0.96 (0.32, 2.88) | 0.23 | 0.94 | 1.39 (0.67, 2.88) | 0.91 | 0.38 | 0.75 (0.46, 1.23) | 0.31 | 0.25 |

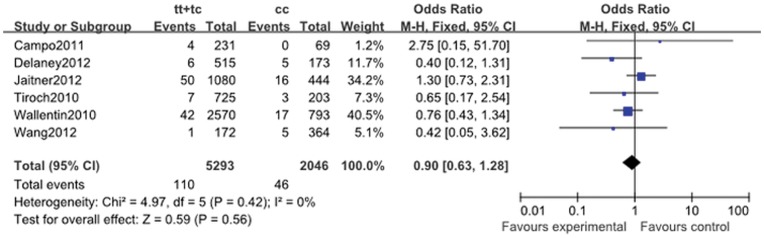

| Thrombosis | 0.97 (0.61, 1.53) | 0.06 | 0.88 | 1.60 (0.96, 2.68) | 0.14 | 0.07 | 1.06 (0.74, 1.52) | 0.34 | 0.75 | 0.90 (0.63, 1.28) | 0.42 | 0.56 |

| Bleeding | 1.00 (0.88, 1.13) | 0.76 | 0.98 | 0.51 (0.40, 0.66) | 0.39 | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.87, 1.28) | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.98 (0.80, 1.20) | 0.55 | 0.83 |

P value of Q-test for heterogeneity test.

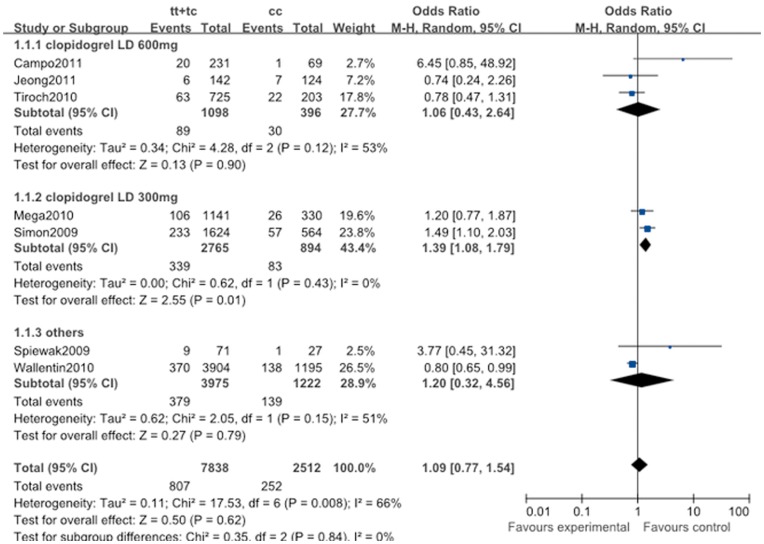

2.2. Long-term major adverse cardiovascular events

The major adverse cardiovascular events (more than one year) had no significant association with ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism in all genotype genetic models (for CT + TT vs. CC: OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.54; P = 0.62; Fig. 3). The I2 statistic indicated the between-study heterogeneity (Table 11).

Figure 3. Pooled random-effects-based odds ratio of long-term major adverse cardiovascular events associated with ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism.

Comparison: TT+TC vs. CC.

The effect of the ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism was further evaluated in stratification analyses. According to the clopidogrel loading dose, we found that this polymorphism was associated with the risk of the MACE in patients treated with clopidogrel LD 300 mg in allele comparison (T vs. C: OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.48; P = 0.001), homozygote comparison (TT vs. CC: OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.19 to 2.13; P = 0.002), and dominant genetic model (CT + TT vs. CC: OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.79; P = 0.01; Fig. 3). However, no significant risk of the MACE in other subgroups with this polymorphism was observed in all comparisons. Meanwhile, the heterogeneity of each subgroup was decreased (Table 11).

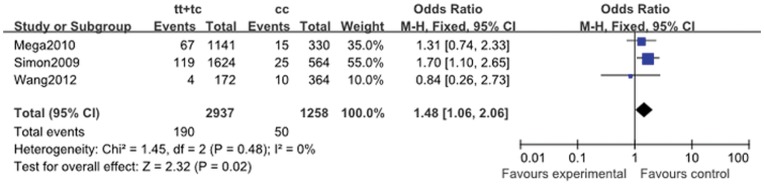

2.3. Early major adverse cardiovascular events

Three studies provided data (MACE happened in about one month), and the heterogeneity was low for all comparisons except for that of TT vs. CC + CT (I2 = 72%; P = 0.016) (Table 11). The overall meta-analysis demonstrated that significantly elevated risk was associated with the ABCB1 C3435T variation in allele comparison (T vs. C: OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.62; P = 0.003), homozygote comparison (TT vs. CC: OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.19 to 2.63; P = 0.005), and dominant genetic model (CT + TT vs.CC: OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.06 to 2.06; P = 0.02; Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Pooled fix-effects-based odds ratio of early major adverse cardiovascular events associated with ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism.

Comparison: TT+TC vs. CC.

2.4. Myocadial infarction

Myocadial infarction in the five cohort studies included in the primary analysis was 5.10% (200 of the 3923 patients). The summary ORs showed no association between ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and risk of MI in the follow-up period (for CT + TT vs. CC: OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.57 to 1.58; P = 0.84; Fig. 5). Analysis showed that the heterogeneity existed in the homozygote comparison (I2 = 76%; P = 0.04) and recessive genetic model (I2 = 71%; P = 0.03) (Table 11).

Figure 5. Pooled fix-effects-based odds ratio of myocardial infarction associated with ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism.

Comparison: TT+TC vs. CC.

2.5. Ischemic stroke

The ischemic stroke rate in the five cohort studies was 0.69% (54 of the 7858). As described in Table 11, though no heterogeneity could be detected, the meta-analysis illustrated that ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism was unrelated to the rate of ischemic stroke in patients treated with clopidogrel (for CT + TT vs. CC: OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.54 to 1.96; P = 0.93; Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Pooled fix-effects-based odds ratio of stroke associated with ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism.

Comparison: TT+TC vs. CC.

2.6. All-cause mortality

A total of 97 deaths (four trials, 3387 total patients) occurred during follow-up. When all eligible studies were pooled, the association between all-cause and the ABCB1 C3435T variation was not significant (for CT + TT vs. CC: OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.54; P = 0.62; Fig. 7). No between-study heterogeneity was identified (Table 11).

Figure 7. Pooled fix-effects-based odds ratio of all-cause mortality associated with ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism.

Comparison: TT+TC vs. CC.

2.7. Stent thrombosis

Seven cohort studies reported stent thrombosis data (1.97%, 173 of the 8775). The cumulative incidence of stent thrombosis was not associated with ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism in all genotype genetic models (for CT + TT vs. CC: OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.63 to 1.28; P = 0.56; Fig. 8). The heterogeneity existed in allele comparison (I2 = 59%; P = 0.06) (Table 11).

Figure 8. Pooled fix-effects-based odds ratio of thrombosis associated with ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism.

Comparison: TT+TC vs. CC.).

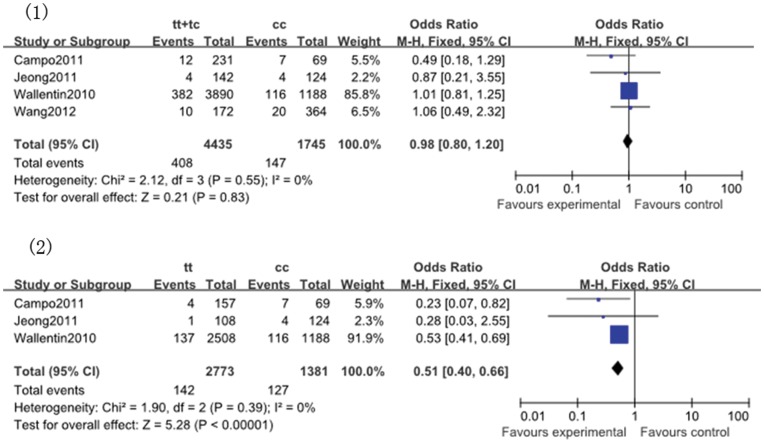

2.8. Bleeding

The bleeding rate in the five cohort studies was 7.82% (596 of the 7619). The comparison of TT vs. CC was associated with a significant reduction in the outcome of bleeding (TT vs. CC: OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.66; P<0.00001; Fig. 9). No significance between ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and other genetic models as well as heterogeneity were identified (Table 11).

Figure 9. Pooled fix-effects-based odds ratio of bleeding associated with ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism.

Comparison: (1) TT+TC vs. CC;(2) TT vs. CC.

3. Test of Heterogeneity

In platelet activity studies, there was significant heterogeneity in three genetic contrasts of the ABCB1 C3435T (Table 11). However, in the subgroup analysis, heterogeneity disappeared in studies that tested the platelet activity by light transmittance aggregometry (LTA) and the VerifyNow (T vs. C: I2 = 11%, P = 0.29; TT vs. CC: I2 = 0%, P = 0.61; TT+CT vs. CC I2 = 22%, P = 0.28).

Furthermore, significant heterogeneity existed in all the four genetic models of the ABCB1 C3435T with long-term MACE (Table 11). But in the subgroup analysis of clopidogrel loading dose, the heterogeneity of each subgroup was changed, clopidogrel LD 300 mg in two contrasts (T vs. C: I2 = 0%, P = 0.53; TT vs. CC: I2 = 0%, P = 0.79; TT+CT vs. CC I2 = 0%, P = 0.43) except one model (TT vs. TC+CC: I2 = 63%, P = 0.10), as well as clopidogrel LD 600 mg in two contrasts (T vs. C: I2 = 41%, P = 0.19; TT vs. TC+CC: I2 = 19%, P = 0.27; TT+CT vs. CC I2 = 53%, P = 0.12) except one model(TT vs. CC: I2 = 70%, P = 0.07).

In addition, the heterogeneity existed in allele comparison with regard to stent thrombosis (Table 11). When we stratified the trials by previous or current smoker percentage, the heterogeneity was not clear in the subgroup (percentage <50%) (T vs. C: I2 = 0%; P = 0.32) and the other (percentage >50%) (T vs. C: I2 = 34%; P = 0.22).

Although we also found the heterogeneity in two genetic model contrasts of Myocadial infarction and one genetic model contrast of early MACE (Table 11), due to limited studies, we failed to explain the heterogeneity. Finally, the heterogeneity could not be detected significantly in other contrasts.

4. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed in the ABCB1 C3435T dominant genetic model (CT + TT vs. CC). The significance of pooled ORs was not obviously affected by omission of individual studies except for MACE. One study [16] carried the greatest weight for long-term MACE. When it was excluded, the pooled p-values were significant in all comparisons, whereas exclusion of any other did not influence the results. Similarly, exclusion of the study by Simon et al. [9], the pooled OR of the dominant genetic model in early MACE was not significant. Meanwhile, in this genetic model, the heterogeneity in our meta-analysis was not influenced excessively by exclusion of any single study.

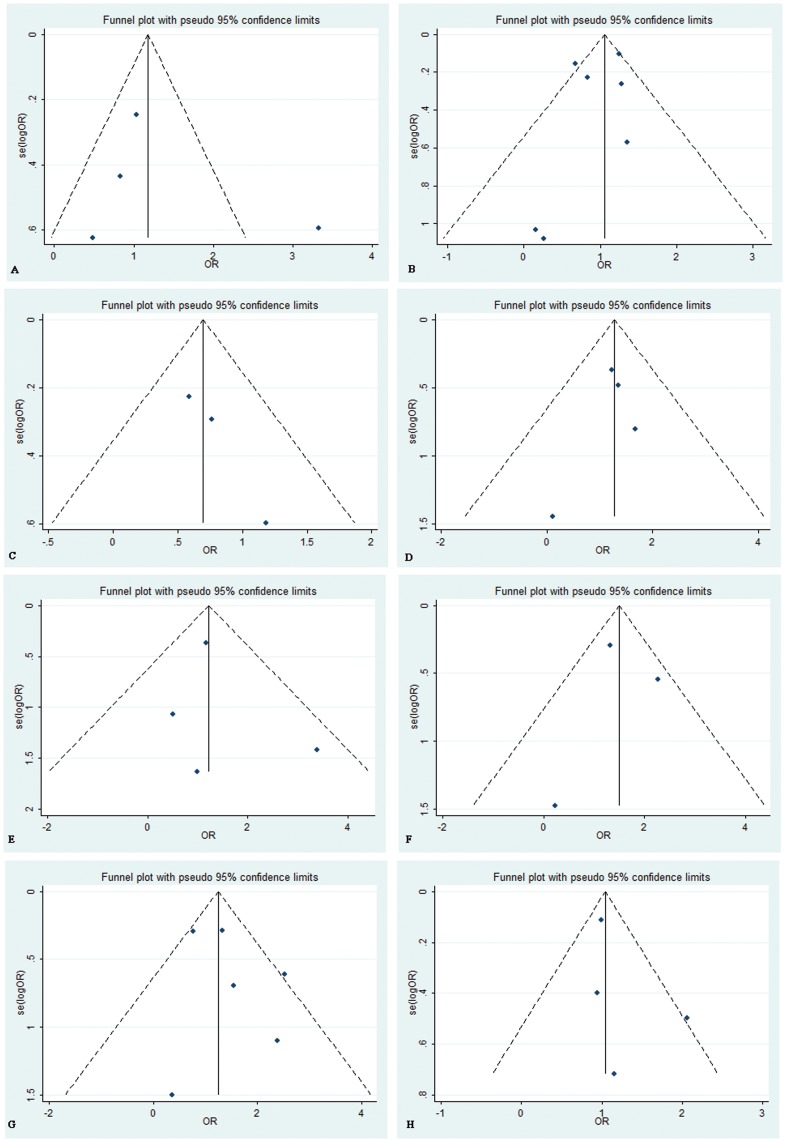

5. Publication Bias

Funnel plot as well as Begg’s and Egger’s tests were carried out to access the publication bias of studies. Data showed that there was no evidence of publication bias in comparison of TT+TC vs. CC (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. Funnel plots of the meta-analysis of ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism (comparison: TT+TC vs. CC) and response to clopidogrel treatment.

(A) platelet activity (Begg’s test, P = 1.000; Egger’s test, P = 0.402);(B) Long-term major adverse cardiovascular events (Begg’s test, P = 1.000; Egger’s test, P = 0.474);(C) Early major adverse cardiovascular events (Begg’s test, P = 0.296; Egger’s test, P = 0.124);(D) myocardial infarction (Begg’s test, P = 1.000; Egger’s test, P = 0.628);(E) stroke (Begg’s test, P = 0.734; Egger’s test, P = 0.693);(F) All-cause mortality (Begg’s test, P = 1.000; Egger’s test, P = 0.990);(G) Stent thrombosis (Begg’s test, P = 1.000; Egger’s test, P = 0.372);(H) Bleeding(Begg’s test, P = 0.308; Egger’s test, P = 0.425). OR = odds ratio; se = standard error.

Discussion

Clopidogrel, as a pro-drug, was known to require metabolic activation before inhibiting platelet aggregation. The ABCB1 C3435T had been revealed to be associated with loss of function of P-glycoprotein which decreased the active metabolite of clopidogrel. On the basis of antiplatelet responding in the laboratory test and poor clinical outcomes, several molecular cardiovascular studies were conducted to evaluate the association between the ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and platelet response in CAD patients on clopidogrel, but the results were inconclusive. A former meta-analysis [35] showed that the association might exist between TT homozygotes of the ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and risk of short-term recurrent ischemic events.

In the present meta-analysis, since we included newer studies [11], [14], [19], [20] and conducted the research more meticulously with the subgroup study and more detailed trials which the former one had not included, new significance resulted. To begin with, the 3435T allele carrier was related with the risk of the early and long-tern major adverse cardiovascular events in patients treated with clopidogrel LD 300 mg. However, we did not find the significant association in subgroup clopidogrel LD 600 mg and others. Simon et al. [9] first found that patients with TT genotype had a higher rate of subsequent cardiovascular events than those with CC genotype. The recent clinical trial showed that compared with a 300-mg loading dose, pre-treatment with a 600-mg clopidogrel loading dose before primary PCI was associated with improvement of angiographic results and 30-day major adverse cardiovascular events [36]. The platelet response in treatment might be influenced by both ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and clopidogrel loading dose, which need further research to identify. Meanwhile another study [37] indicated that a 150 mg oral maintenance dose of clopidogrel resulted in more intense inhibition of platelet aggregation than a 75 mg maintenance dose, which suggested that the maintenance dose also interacted with the platelet activity. In addition, TT homozygotes decreased the outcome of bleeding compared with CC homozygotes in our meta-analysis. This was almost consistent with the result from the three respective trails [14], [16], [18]. However, one study [16] carried the greatest weight for this analyses and with limited studies included, the result should be interpreted with caution and further studies based on larger, stratified population should be examined.

Four studies [10], [12]–[14] on platelet activity tested by different methods were included in our research. This was the first meta-analysis that includes the studies on the polymorphism with the degree of platelet inhibition evaluated by empirical methods, though no significance was searched. Meanwhile, in the group of all-cause mortality, MI, Stroke, and stent thrombosis, the polymorphisms with them were also not significant. Various factors may inference these. Among them, we first pay attention to the evidence of heterogeneity, for which the reasons are unclear. It may be due to the following: the selection of methods; differences in age, gender, ethnicity, sample size; and the main clinical characteristics. For instance, the diabetes with insulin resistance lower the inhibition of platelet aggregation [38]. Various genotyping methods applied in different studies may also bring about the heterogeneity. Diverse definition of case in platelet activity tests were used, such as different time of evaluation, hence, the association mignt have been biased or simply lead to heterogeneity. If we carried out the subgroup by some of the above elements, the heterogeneity in some compares decreased.

Clopidogrel inhibits the platelet activity, and high platelet activity in patients treated with Clopidogrel indicates clopidogrel resistance or poor response to clopidogrel, which will lead to poor clinical outcome in the future. Though we have found some association between ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and antiplatelet responding, we also should set our insights to the interaction between single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and other factors. As coexisting, rather than single, polymorphisms in different genes may be related to persistent platelet activation while on clopidogrel [39], so gene-gene interaction, such as P2Y12 or CYP2C19 with ABCB1 C3435T, should also be observed between ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and antiplatelet responding. On the other hand, one recent research [40] showed that the combination of a calcium channel blocker and ABCB1 C3435T genotype influenced the change of 20 µmol ADP-induced maximal platelet aggregation (MPA) in smoking status receiving clopidogrel. In our meta-analysis, the small scale of population and inconsistent stratification standards in environmental exposures and genotypes lowered our statistical power to further explore the gene-environment interaction. As a result, we need to give careful consideration to more sophisticated gene-gene and gene-environment interactions in a future analysis, so as to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the association between ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and antiplatelet responding.

Besides, from the different aspirin doses or triple antiplatelet therapy our studies included, we believe that interaction between gene and drug combination may also exist. Prolonged use of aspirin may reduce the intestinal absorption of clopidogrel by inducing the expression of ABCB1 in human epithelial colorectal (Caco-2) cells [41]. Researchers recently started to focus on the interactions between genetic polymorphisms and clinical effect with triple antiplatelet therapy (cilostazol, clopidogrel and aspirin) [12]. All these have urged us to pay more attention to the interaction between gene and drug combination in using clopidogrel. However, since new antiplatelet medicine had gone to market, we discovered that ABCB1 genotypes were not significantly associated with clinical or pharmacological outcomes in patients treated with prasugrel [15] and the pharmacodynamic characteristics of ticagrelor were not influenced by CYP2C19 and ABCB1 genotypes [42]. These might overcome the difficulty in poor antiplatelet responding the ABCB1 genotypes associated and gave us fresh insight to the antiplatelet treatment in addition to aspirin and clopidogrel, however numerous trails should be arranged for further assessment.

Although considerable efforts have been put into the test, there are some limitations inherent in the study. First, the number of studies included are limited, especially for the information on the risk of MACE in patients treated with clopidogrel LD 300 mg and the outcome of bleeding. Thus the conclusion about these should be considered with caution. Second, detailed information such as the ethnicity and other main characteristic are not available in some studies, which further limit our evaluation. Third, gene-gene or gene-environment interaction, different loading or maintenance dose, influence from main clinical characteristics, standardized unbiased platelet activity evaluation and genotyping methods may affect the results. These variables can be planned more effectively by a separate analysis of these elements, to which we did not have access.

In summary, our meta-analysis indicated that the ABCB1 3435T allele carrier was related to the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients on clopidogrel LD 300 mg, and TT homozygotes decreased the outcome of bleeding compared with CC homozygotes, whereas, the association between ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and platelet activity as well as other risks of poor clinical outcomes were not significant. Thus, to validate our findings, additional larger studies need to focus on homogeneous cases along with standardized platelet activity evaluation and genotyping methods in further tasks.

Supporting Information

PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful and thank Dr. Jessica Tod Delaney and Dr. Gianluca Campo providing additional information and data on their studies. We also thank all the participants in this study.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1. Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, Bridges CR, Casey DE Jr, et al. (2011) 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update of the Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (updating the 2007 guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 1920–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Hiatt BL, O’Connor CM (2003) Clopidogrel for coronary stenting: response variability, drug resistance, and the effect of pretreatment platelet reactivity. Circulation 107: 2908–2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matetzky S, Shenkman B, Guetta V, Shechter M, Beinart R, et al. (2004) Clopidogrel resistance is associated with increased risk of recurrent atherothrombotic events in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 109: 3171–3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hochholzer W, Trenk D, Bestehorn HP, Fischer B, Valina CM, et al. (2006) Impact of the degree of peri-interventional platelet inhibition after loading with clopidogrel on early clinical outcome of elective coronary stent placement. J Am Coll Cardiol 48: 1742–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campo G, Fileti L, Valgimigli M, Tebaldi M, Cangiano E, et al. (2010) Poor response to clopidogrel: current and future options for its management. J Thromb Thrombolysis 30: 319–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gros P, Ben Neriah YB, Croop JM, Housman DE (1986) Isolation and expression of a complementary DNA that confers multidrug resistance. Nature 323: 728–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fojo A, Lebo R, Shimizu N, Chin JE, Roninson IB, et al. (1986) Localization of multidrug resistance-associated DNA sequences to human chromosome 7. Somat Cell Mol Genet 12: 415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taubert D, von Beckerath N, Grimberg G, Lazar A, Jung N, et al. (2006) Impact of P-glycoprotein on clopidogrel absorption. Clin Pharmacol Ther 80: 486–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, Quteineh L, Drouet E, et al. (2009) Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 360: 363–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spiewak M, Malek LA, Kostrzewa G, Kisiel B, Serafin A, et al. (2009) Influence of C3435T multidrug resistance gene-1 (MDR-1) polymorphism on platelet reactivity and prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Kardiol Pol 67: 827–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang XD, Zhang DF, Liu XB, Lai Y, Qi WG, et al. (2012) Modified clopidogrel loading dose according to platelet reactivity monitoring in patients carrying ABCB1 variant alleles in patients with clopidogrel resistance. Eur J Intern Med 23: 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim IS, Jeong YH, Park Y, Yoon SE, Kwon TJ, et al. (2012) Interaction analysis between genetic polymorphisms and pharmacodynamic effect in patients treated with adjunctive cilostazol to dual antiplatelet therapy: results of the ACCEL-TRIPLE (Accelerated Platelet Inhibition by Triple Antiplatelet Therapy According to Gene Polymorphism) study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 73: 629–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jeong YH, Kim IS, Park Y, Kang MK, Koh JS, et al. (2010) Carriage of cytochrome 2C19 polymorphism is associated with risk of high post-treatment platelet reactivity on high maintenance-dose clopidogrel of 150 mg/day: results of the ACCEL-DOUBLE (Accelerated Platelet Inhibition by a Double Dose of Clopidogrel According to Gene Polymorphism) study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 3: 731–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jeong YH, Tantry US, Kim IS, Koh JS, Kwon TJ, et al. (2011) Effect of CYP2C19*2 and *3 loss-of-function alleles on platelet reactivity and adverse clinical events in East Asian acute myocardial infarction survivors treated with clopidogrel and aspirin. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 4: 585–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Walker JR, et al. (2010) Genetic variants in ABCB1 and CYP2C19 and cardiovascular outcomes after treatment with clopidogrel and prasugrel in the TRITON–TIMI 38 trial: a pharmacogenetic analysis. The Lancet 376: 1312–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wallentin L, James S, Storey RF, Armstrong M, Barratt BJ, et al. (2010) Effect of CYP2C19 and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on outcomes of treatment with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel for acute coronary syndromes: a genetic substudy of the PLATO trial. Lancet 376: 1320–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tiroch KA, Sibbing D, Koch W, Roosen-Runge T, Mehilli J, et al. (2010) Protective effect of the CYP2C19 *17 polymorphism with increased activation of clopidogrel on cardiovascular events. Am Heart J 160: 506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Campo G, Parrinello G, Ferraresi P, Lunghi B, Tebaldi M, et al. (2011) Prospective evaluation of on-clopidogrel platelet reactivity over time in patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention relationship with gene polymorphisms and clinical outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 2474–2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Delaney JT, Ramirez AH, Bowton E, Pulley JM, Basford MA, et al. (2012) Predicting clopidogrel response using DNA samples linked to an electronic health record. Clin Pharmacol Ther 91: 257–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jaitner J, Morath T, Byrne RA, Braun S, Gebhard D, et al. (2012) No association of ABCB1 C3435T genotype with clopidogrel response or risk of stent thrombosis in patients undergoing coronary stenting. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 5: 82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Woolf B (1955Jun) On estimating the relation between blood group and disease. Ann Hum Genet 19(4): 251–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH (1997) Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med 127: 820–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327: 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sutton AJ, Duval SJ, Tweedie RL, Abrams KR, Jones DR (2000) Empirical assessment of effect of publication bias on meta-analyses. BMJ 320: 1574–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Begg CB (2002) A comparison of methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis by P. Macaskill, S. D. Walter and L. Irwig, Stat Med, 2001. 20: 641–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bouman HJ, Schomig E, van Werkum JW, Velder J, Hackeng CM, et al. (2011) Paraoxonase-1 is a major determinant of clopidogrel efficacy. Nat Med 17: 110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bonello L, Camoin-Jau L, Mancini J, Bessereau J, Grosdidier C, et al. (2012) Factors associated with the failure of clopidogrel dose-adjustment according to platelet reactivity monitoring to optimize P2Y12-ADP receptor blockade. Thromb Res 130: 70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Simon T, Steg PG, Becquemont L, Verstuyft C, Kotti S, et al. (2011) Effect of paraoxonase-1 polymorphism on clinical outcomes in patients treated with clopidogrel after an acute myocardial infarction. Clin Pharmacol Ther 90: 561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Simon T, Bhatt DL, Bergougnan L, Farenc C, Pearson K, et al. (2011) Genetic polymorphisms and the impact of a higher clopidogrel dose regimen on active metabolite exposure and antiplatelet response in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther 90: 287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rideg O, Komocsi A, Magyarlaki T, Tokes-Fuzesi M, Miseta A, et al. (2011) Impact of genetic variants on post-clopidogrel platelet reactivity in patients after elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Pharmacogenomics 12: 1269–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gladding P, Webster M, Zeng I, Farrell H, Stewart J, et al. (2008) The pharmacogenetics and pharmacodynamics of clopidogrel response: an analysis from the PRINC (Plavix Response in Coronary Intervention) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 1: 620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sharma V, Kaul S, Al-Hazzani A, Prabha TS, Rao PP, et al. (2012) Association of C3435T multi drug resistance gene-1 polymorphism with aspirin resistance in ischemic stroke and its subtypes. J Neurol Sci 315: 72–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cayla G, Hulot JS, O’Connor SA, Pathak A, Scott SA, et al. (2011) Clinical, angiographic, and genetic factors associated with early coronary stent thrombosis. JAMA 306: 1765–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Luo M, Li J, Xu X, Sun X, Sheng W (2012) ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism and risk of adverse clinical events in clopidogrel treated patients: A meta-analysis. Thromb Res 129: 754–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Patti G, Barczi G, Orlic D, Mangiacapra F, Colonna G, et al. (2011) Outcome comparison of 600- and 300-mg loading doses of clopidogrel in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from the ARMYDA-6 MI (Antiplatelet therapy for Reduction of MYocardial Damage during Angioplasty-Myocardial Infarction) randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 1592–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. von Beckerath N, Kastrati A, Wieczorek A, Pogatsa-Murray G, Sibbing D, et al. (2007) A double-blind, randomized study on platelet aggregation in patients treated with a daily dose of 150 or 75 mg of clopidogrel for 30 days. Eur Heart J 28: 1814–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Angiolillo DJ, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Bernardo E, Ramirez C, Sabate M, et al. (2005) Platelet function profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease on combined aspirin and clopidogrel treatment. Diabetes 54: 2430–2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Malek LA, Spiewak M, Grabowski M, Filipiak KJ, Kostrzewa G, et al. (2008) Coexisting polymorphisms of P2Y12 and CYP2C19 genes as a risk factor for persistent platelet activation with clopidogrel. Circ J 2008 Jul 72(7): 1165–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Park Y, Jeong YH, Tantry US, Ahn JH, Kwon TJ, et al. (2012) Accelerated platelet inhibition by switching from atorvastatin to a non-CYP3A4-metabolized statin in patients with high platelet reactivity (ACCEL-STATIN) study. Eur Heart J 2012 Sep 33(17): 2151–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jung KH, Chu K, Lee ST, Yoon HJ, Chang JY, et al. (2011) Prolonged use of aspirin alters human and rat intestinal cells and thereby limits the absorption of clopidogrel. Clin Pharmacol Ther 90: 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Teng R (2012) Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and pharmacogenetic profile of the oral antiplatelet agent ticagrelor. Clin Pharmacokinet 51: 305–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

(DOC)