Abstract

Endometrial decidualization, a process essential for blastocyst implantation in species with hemochorial placentation, is accompanied by an enormous but transient influx of Natural Killer (NK) cells. Mouse uterine (u)NK cell subsets have been defined by diameter and cytoplasmic granule number, reflecting stage of maturity and by histochemical reactivity with Periodic Acid Schiff’s (PAS) reagent, with or without co-reactivity with Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) lectin. We asked whether DBA− and DBA+ mouse uNK cells were equivalent using quantitative (q)RT-PCR analyses of flow separated, midpregnancy (gestation day (gd)10) cells and using immunohistochemistry. CD3E (CD3)-IL2RB (CD122)+DBA− cells were identified as the dominant Ifng transcript source. Skewed IFNG production by uNK cell subsets was confirmed by analysis of uNK cells from eYFP-tagged IFNG-reporter mice. In contrast, CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ uNK cells expressed genes compatible with significantly greater potential for IL22 synthesis, angiogenesis and participation in regulation mediated by the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ cells were further divided into VEGFA+ and VEGFA− subsets. CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ uNK cells but not CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− uNK cells arose from circulating, bone marrow-derived progenitor cells by gd6. These findings indicate the heterogeneous nature of mouse uNK cells and suggest that studies using only DBA + uNK cells will give biased data that does not fully represent the uNK cell population.

Keywords and Topic Category: Cytokines, Decidua, Immunology, Pregnancy, Uterus

INTRODUCTION

“Innate lymphoid cells” (ILC) describes an expanding category of mucosa-associated cells that differentiate from common lymphoid progenitor cells during fetal development and adulthood. ILCs include Natural Killer cells, lymphoid tissue inducer cells (LTI), NK cells that produce IL22 (NK22 cells) and cells known as ILC1 and ILC2 cells [1]. ILC1 cells are producers of IL12, IL15 and IL18 while ILC2 cells produce IL25 and IL33. Transient cells, known as uterine (u)NK cells, become abundant in mice, as in humans, during decidualization and they promote physiological changes in endometrial structure that are associated with early pregnancy, including development of a transient lymphoid structure (mesometrial lymphoid aggregrate of pregnancy; MLAp) that surrounds vessels associated with each placenta [2]. Relationships between uNK cells and other ILCs are undefined. Mouse uNK cells are recognized histochemically as containing glycoprotein-rich, cytoplasmic granules that react with Periodic Acid Schiff’s (PAS) reagent or Dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) lectin from gestation day (gd)5 [3–5]) but potential subset functions have not been addressed. UNK cell origins are not fully defined but, upon adoptive cell transfer, mouse uNK cells arise from progenitors found in primary and secondary lymphoid organs of male and of female mice and become highly proliferative within early decidua [3;6]. UNK cells reach maximum numbers at midgestation (gd10-12) and are numerically reduced by term (gd19-20) [3;4;7;8]. UNK cells produce cytokines and have angiogenic functions, including initiating roles in the gestational remodeling that enlarges capacity of spiral arteries (SA), the major placental supply vessels [9–12].

Using dual reagent histochemistry with DBA lectin (reactive with molecules having N-acetylgalactosamine as their terminal sugar) and PAS, all mouse uNK cells are identified and they have only one of two phenotypes, PAS+DBA− or PAS+ DBA+ [13]. Both subsets show terminal differentiation into very large cells with a heavily granulated cytoplasm; no differences are known between these subsets beyond DBA lectin reactivity documented in multiple strains (B6 [13], BALB/c, CD1 (our unpublished data). The two mouse uNK cell subsets are equal in abundance early during decidualization (gd6) but, by midgestation, PAS+ DBA− uNK cells are outnumbered 1:9 by PAS+DBA+ uNK cells. We wished to determine whether the potential functions of PAS+DBA− and PAS+DBA+ uNK cells were similar or divergent using mRNA analysis. However, the PAS reaction degrades RNA. Therefore, we used flow cytometry sorting to purify the uNK cell subsets. The protocol of Yadi et al. was adopted to flow sort gd10 CD3E-IL2RB+ decidual leukocytes from high fecundity CD1 mice into DBA− and DBA+ subsets [14] for RNA isolation. Yadi et al. suggest that the CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− population resembles peripheral NK cells while the CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ population is unique to decidualized endometrial mucosa [14].

Our analyses targeted three distinct biological processes: cytokine production (Ifng and Il22), angiogenesis (Pgf and Vegfa) and regulation via the renin-angiotensin system (RAS: Agt (Angiotensinogen); the angiotensinogen to angiotensin pathway cleaving enzymes Ren1 (Renin), Cma1 (Chymase 1), Ace (Angiotensin I converting enzyme 1); Agtr1and Agtr2 (Angiotensin receptors) and Nppa (Natriuretic peptide type A; the gene encoding an antagonist of AGTR1-mediated vasoconstriction)). IFNG peaks in mouse decidua basalis (DB) at gd10-12, in CD1, B6, and BALB/c mice coincident with highest uNK cell numbers [10;15]. About 90% of decidual IFNG is uNK cell-derived [15] and it provides the initiating step in spiral arterial modification [10]. IL22 is a leukocyte-derived cytokine produced by several subsets of activated T cells and spontaneously by ILCs, including NK22 cells and dendritic cells. IL22 acts in intestinal defense, contributes to mucosal wound healing and is reported in immature but not mature human uNK cells [16–18]. PGF and VEGFA are known uNK cell products of [11;19;20]. RAS components were studied because they are reported in mouse T cells where they enhance responsiveness to vasopressors [21] and in human NK and T cells [22] and because of the clinical relationship linking incomplete spiral arterial modification, an outcome associated with uNK cell deficiency, with gestational complications including hypertension in humans [23]. At midgestation, CD3E− IL2RB+DBA− cells differed significantly from more abundant CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ uNK cell populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Male and female CD1 (Charles River, St. Constant, QU), Yellow-enhanced transcript for IFNG (EYFP; Yeti) mice on the C57BL/6 (B6) background (a kind gift from G. Stockinger, NIMR, London [24]), B6, BALB/cJ (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and BALB/c-Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− (Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/; Queen’s University colony) were used in this study. Males served as studs for pairing with 8–12wk old estrous females; copulation plug detection was called gd0. Mated females were anaesthetized then euthanized by cervical dislocation on specific gd and their uteri were dissected. Control spleens and kidneys were dissected from non pregnant mice. Archived histological specimens (4% paraformaldehyde fixed, paraffin embedded) from a B6 tissue bank were used for immunohistochemistry [25] unless otherwise noted. Animal usage complied with national guidelines of each country and was conducted under protocols approved at each participating institution. For flow sorting, gd10 DB and the transient, uterine wall-localized MLAp were dissected as separate tissues (placenta and fetus excluded), then pooled and mechanically dissociated as in [14;25]. Two flow sorting experiments used one CD1 pregnancy each; two experiments pooled two gd10 CD1 pregnancies each.

Histological Methods

Five μm paraffin sections mounted on glass slides were cleared, rehydrated and blocked (1h, R°C; Serum Free Protein Block, Dako; Mississauga, ON). The following primary antibodies, diluted in sodium azide-supplemented antibody diluent with 0.1% Tween (Dako) were used: biotinylated rat anti-mouse IFNG mAb (1:100; Mabtech AB, Stockholm, SE); rat anti-mouse perforin (PRF1;1:50; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and rabbit antibodies from Abcam to IL22 (1:200), PGF (1:500), VEGFA (1:200), REN1 (1:200), ACE (1:200); AGTR1 (1:200), AGTR2 (1:200) and in house prepared to NPPA (1:200) [26]. After incubation with primary antibodies (16h; 4°C), sections were washed and incubated (2h; R°C) with Alexa594-tagged goat anti-rabbit or anti-rat secondary antibody (1:200, Invitrogen; Burlington, ON) or Alexa594− or 488− tagged streptavidin (Sigma; Oakville, ON). Sections were then incubated (2h, R°C) with FITC-conjugated DBA lectin (Sigma; [25]) followed by 20mM L-lysine (Sigma) to quench autofluorescence and cover-slipped with DAPI-supplemented mounting media (ProLong Gold Anti-fade Reagent with DAPI, Invitrogen). Photomicrographs were collected using an AxioCam equipped Zeiss M1 Imager with Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss; Toronto, ON) or using an Eclipse 800 imaging system (Nikon, Japan) equipped with Image ProPlus software (Media Cybernetic, Bethesda MD, USA).

To define antibody and lectin staining against PAS+ cells, coverslips were removed from the photographed, fluorochrome-reacted slides, tissues were equilibrated in PBS and routine PAS histochemical staining with 1% amylase digestion was done [27]. The order of staining could not be reversed since PAS emits red fluorescence at 555–625 nm [28]. Slides were dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in xylene, coverslipped with Permount (Fisher; Ottawa, ON, Canada) and then re-photographed over the same field.

For enumeration of DBA+ and DBA− uNK cells expressing VEGFA, gd7, 9 and 14 BALB/c implant sites were examined using 21 to 60 fluorescence photomicrographs (200X) from randomly selected mesometrial areas. Nuclear DAPI was used to estimate total cell number aided by Manual Point Count (Image ProPlus 6) as well as numbers of antibody-reactive or lectin-reactive cells. For enumeration of PAS+DBA− cells in BM− engrafted gd6 Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− in dual PAS-DBA stained sections [13], >1000 uNK cells were visually scored under oil immersion microscopy using multiple implant sites from 2 pregnancies.

Cell Subset Separation and Quantitative (q)RT-PCR

Suspensions of gd10 DB and MLAp were incubated in 1% BSA, then stained (30 min, 4°C) with FITC-conjugated DBA (0.1 g/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and antibodies from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA): PE-conjugated anti-mouse IL2RB (1/100; clone 5H4;) and PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-mouse CD3E (1/100; clone 145-2C11). Forward and side scatter properties were used to set the initial gates, then CD3E-IL2RB+ cells were μ gated, sorted as DBA− or DBA+ cells and collected using an EPICS Altra Flow Hy-PerSort Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Mississauga ON). A representative outcome is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1A. Cell yields were ~100–200 CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− cells and ~1000–1800 CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ cells. FACS analysis of gd9 decidual cell suspensions from Yeti mice was as described in [14].

In a flow sorting validation experiment, some cells were labeled with IL2RB-PE, CD19-FITC (1:200 eBiosciencs) and EMR1 (F4/80)-FITC (1:100, eBiosciences) to evaluate possible selection of IL2RB+ B cells or macrophages. 0.5% of the FACS analysed IL2RB+ cells appeared in the FITC channel. In this experiment, post-sort CD3E-IL2RB+DBA- cells were placed in a drop on a glass slide, dried, fixed in methanol, simultaneously stained with DAPI, CD19-FITC and EMR1-FITC and examined microscopically under ultraviolet illumination. No sorted cells fluoresced green while diluted splenocyte suspensions similarly prepared contained CD19+ and EMR1+ cell populations. In the 3 remaining experiments, sorted cells were lysed and RNA was isolated using a PicoPure isolation kit (Molecular Devices; Toronto, ON) following manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was reverse transcribed and amplified using the Ovation Pico WTA System (NuGEN,San Carlos, CA) to PCR template cDNA. qRT-PCR used the ABI Prism 7500 system with TaqMan® Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays containing primers and TaqMan probes were purchased from ABI as follow; Mm01168134_m1(Ifng), Mm00444241_m1(Il22), (Mm01192943_m1)(Il22ra1), Mm00435613_m1(Pgf), Mm01281449_m1(Vegfa), Mm02342889_g1(Ren1), Mm00802048_m1(Ace), Mm00487638_m1(Cma1), Mm0059962_m1(Agt), Mm00616371_m1(Agtr1a), Mm01341373_m1(Agtr2), Mm01255747_g1(Nppa), and Mm01545399_m1(hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase; Hprt). PCR conditions were initial incubation (2 min; 50°C), enzyme heat activation (10 min; 95°C), 40 cycles (15s at 95°C; 1 min at 60°). Relative expression of target transcripts was normalized to Hprt transcripts.

Additional total RNA was prepared from gd10 B6 DB using Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit and from male B6 kidney using Trizol (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg total RNA using Invitrogen SuperScript® III First-Strand Synthesis System. The resulting cDNA was used as template for qRT-PCR as above. Products were run on 1.1% agarose gels.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means±SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Statistical significance for qRT-PCR was assessed by Student’s t test. For the Vegfa time course study, one away ANOVA with Tukey’s post test was used. P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

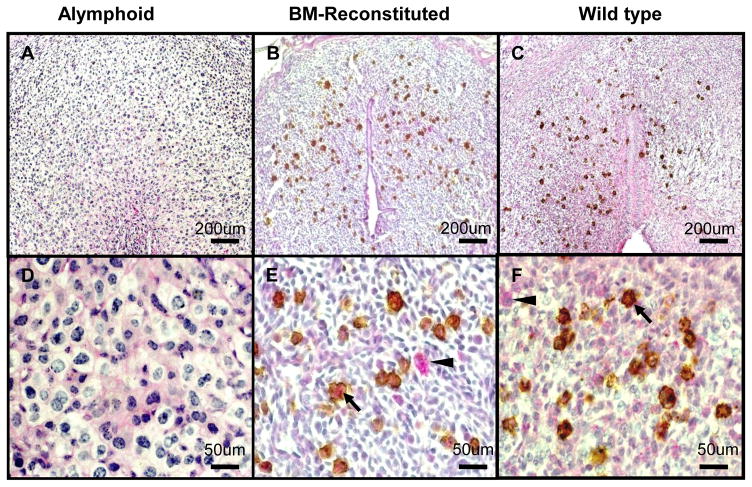

PAS+DBA− uNK cells do not arise from BM-derived progenitors homed to decidua

Previous dual PAS/DBA lectin histochemical analyses of uNK cells differentiating in Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− engrafted by normal syngeneic BM were conducted at gd12 when ~90% of uNK cells in normal mice are DBA+ [13]. That study found DBA− uNK cells were extremely rare (~1/300,000 cells). To more rigorously validate the conclusion that PAS+DBA+ cells arise from homed precursors of BM origin, the study was repeated with analysis at gd6 when PAS+DBA− uNK cells in normal females have their highest ratio of 1.1:1 versus PAS+DBA+ uNK cells [13]. As shown in Fig. 1, almost all uNK cells differentiating from BM are DBA+. PAS+DBA− uNK cells were enumerated at gd6 at 1/230 uNK cells, suggesting that even early in gestation, DBA+ uNK cells arise from uterine homed cells.

Figure 1. DBA+ but not DBA− uNK cells arise from trafficked, BM-derived progenitors.

Gd6.5 DB dually stained with PAS and DBA lectin. Mesometrial side of the uterus is to top. (A, D) Alymphoid Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− DB lacks PAS+DBA− and PAS+DBA+ uNK cells. (B, E) uNK cells in alymphoid Rag2−/−Il2rg−/− reconstituted with BALB/c BM 3 wk previous to mating were PAS+DBA+; PAS+DBA− cells were very rare (1/230 cells-0.0044% total uNK cells). (C, F) About 50% of uNK cells in gd6.5 BALB/c+/+ implant sites are PAS+DBA−, 50% are PAS+DBA+. Arrowheads-PAS+DBA−; Arrows-PAS+DBA+; Size bars 200 μm in (A–C); 50 μm in (D–F).

Mid-pregnancy CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− cells express more IFNG mRNA and protein than CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ cells

Forward and side scatter properties were used to define gd10 CD1 decidual cells selected for flow sorting (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Gates were set to capture CD3E-IL2RB+cells, which were then sorted into DBA− and DBA+ cells. CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ cells were the dominant CD3E-IL2RB+cells (~95%). These were considered to be the uniquely DBA+ decidual leukocytes identified as uNK cells in decidual histology. In early to midgestation normal mouse decidual cell suspensions, macrophages and B cells are the next most abundant CD3E− cells that could also be CD3E-IL2RB+ (B. A. Croy, Z. Chen, A. Hofmann, E. M. Lord, A. L. Sedlacek and S. A. Gerber, Imaging of vascular development in early mouse decidua and its relationships with leukocytes and trophoblasts. MS submitted). Cells with the phenotype IL2RB+ and EMR1+ or CD19+ were 0.5% of the starting cell suspensions used for sorting (not shown). Post sorting analyses were restricted by very low CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− cell yields (100–200 cells) but fluorescence microscopic examination of all sorted CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− cells from one experiment found no EMR1+ or CD19+ cells amongst the recovered cells, all of which had lymphoid appearance. Supplementary Fig. 1A, representative of four independent sorting experiments, shows the gating strategy and sorted cell subsets.

Transcripts for Ifng were 9 fold relatively more abundant at gd10 in CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− than in CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ cells (Fig. 2A). IFNG was detected in gd10 implantation sites by IHC in PAS+ uNK cells that were DBA− and in DBA+ uNK cells (Fig. 2B, C). Staining intensity was visibly greater over DBA− than DBA+ uNK cells (Fig. 2B). This was surprising because IFNG levels increase rapidly in DB between gd6-10 as PAS+DBA− uNK cells decline.

Figure 2. Expression of Ifng by gd9.5-10.5 uNK cells.

(A) Relative Ifng mRNA expression by sorted gd10.5 CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− and CD3E-IL2RB+CD122+DBA+ cells using qRT-PCR normalized to Hprt. Data are means±SEM from cells prepared in three independent sorting experiments. ** P<0.01. (B–C) show the same microscope field with (B) a 3 color merged image shows DAPI, FITC-DBA+ uNK cells and Alexa Fluor® 594-IFNG, (C) shows post-fluorescence staining with PAS to identify all uNK cells. PAS+DBA− uNK cells show intense IFNG staining. PAS+ DBA+ uNK cells are weakly reactive. (D) CD3E-122+ cells from DB and MLAp of gd9 Yeti implantation sites were analysed for ITGA2 (DX5) and KLRB1C (NK1.1). The less frequent ITGA2+ KLRB1C+ cell population, defined previously as DBA− [14], was the strongly YFP+ cell population. Arrowheads-PAS+DBA-cells; Arrows-PAS+DBA+ cells; Size bar (B–C) 20μm.

To confirm greater IFNG production by DBA− than DBA+ uNK cells, gd9 decidual cell suspensions from EYFP-Ifng transgenic females (Yeti mice [24]) were FACS analyzed using antibodies to ITGA2 (DX5) and KLRB1C (NK1.1) to identify uNK cells. IFNG production was attributed to the minor ITGA2+ KLRB1C+ uNK cell subset, previously found to be DBA− (Fig. 2D) rather than to ITGA2− KLRB1C− uNK cells that are DBA+ [14]. Co-localized PAS+DBA− and PAS+DBA+ cells give no histological evidence suggesting functional differences (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

Midpregnancy CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ cells have relatively more transcripts for Il22, Pgf and Vegfa than CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− cells

Il22 transcripts were present in gd10 uNK cells with relative transcript abundance ~8X higher in CD3E-IL2RB+CD122+DBA+ than CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− cells (Fig. 3A). IHC detected IL22 in both DBA+ and DBA− subsets of PAS+ uNK cells (Fig. 3B, C). IL22 staining intensity was greater over uNK cells than over other smaller, IL22+ cell types present in decidua. Il22ra1 expression was not detected in either uNK cell population (data not shown).

Figure 3. Expression of IL22 and PGF by gd10.5 uNK cells.

Relative mRNA expression of Il22 (A) and Pgf (D) by sorted CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− and CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ decidual cells using qRT-PCR normalized to Hprt. Data are means±SEM from cells prepared in three independent sorting experiments. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01. (B–C) show the same microscope field with (B) a 3 color merged image showing DAPI, FITC-DBA+ uNK cells and Alexa Fluor® 594-IL22. (C) shows post-fluorescence staining of these cells with PAS to identify all uNK cells. (E–F) show the same images of a different microscope field with (E) a 3 color merged image showing DAPI, FITC-DBA+ uNK cells and Alexa Fluor® 594-PGF. (F) shows post-fluorescence staining with PAS to identify all uNK cells. Arrowheads-PAS+DBA-cells; Arrows-PAS+DBA+ cells; Size bar represents 20μm.

Pgf transcripts were almost 40X relatively more abundant in gd10 CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ than in CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− cells (Fig. 3D). IHC detected PGF in both DBA− and DBA+ subsets of PAS+ uNK cells (Fig. 3E, F). Immunoreactivity was common over additional gd10 decidual cell types (Fig. 3E).

Vegfa transcripts were ~19X relatively more abundant in gd10 CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ than in CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− cells (Fig. 4A). IHC detected VEGFA in both DBA+ and DBA− subsets of PAS+ uNK cells (Fig. 4B, C). VEGFA staining was less intense over DBA− than DBA+ uNK cells supporting the RNA expression analysis. VEGFA staining intensity was greater over reactive uNK cells (Fig. 4B vs 4C) than over other reactive cell types in decidua basalis. Both Vegf and Pgf transcripts were relatively more abundant than transcripts for Ifng or Il22 in DBA+ uNK cells (see Figures 2, 3, 4).

Figure 4. Expression of VEGFA by uNK cells.

(A) Relative Vegfa mRNA expression by CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− and CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ gd10.5 decidual cells using by qRT-PCR normalized to Hprt. Data are means±SEM from cells prepared in three independent sorting experiments. * P<0.05. (B–C) show the same microscope field with (B) a 3 color merged image showing DAPI, FITC-DBA+ uNK cells and Alexa Fluor® 594-VEGFA. (C) shows post-fluorescence staining with PAS to identify all uNK cells. Arrowheads-PAS+DBA-cells; Arrows-PAS+DBA+ cells. (D) summarizes DBA lectin and VEFGA reactive DAPI+ mesometrial cells in BALB/c implant sites at gd7, 9 and14. White bar DBA+VEGFA−; Grey bar DBA+VEGFA+; Black bar DBA-VEGFA+ cells (gd7, 22 fields from 2 pregnancies; gd9, 43 fields from 3 pregnancies and gd14, 61 fields from 2 pregnancies scored at 200X magnification). * P<0.05, *** P<0.001. (E) Dually stained DB showing in (Ei) PRF1 (perforin, red) that is associated with DBA+ granules (green). Many but not all cells expressed PRF1. (Eii) shows uNK cells containing DBA+ cytoplasmic granules and non granule-associated VEGFA. (Eiii) co-localizes PRF1granules and plasma membrane-associated VEGFA (pseudocolored violet) co-localized to single DBA+ uNK cells. Size bars are 20 μm.

To estimate the proportion of DBA+VEGFA+ uNK cells and to determine if this changed over pregnancy, an IHC time course (gd7-14) study was conducted. At gd7, 28% of VEGFA+ cells co-expressed DBA. At gd9 and 14, VEGFA was more abundant in DBA+ uNK cells (78% and 83% respectively of all decidual VEGFA+ cells; Fig. 4D) although within DBA+ uNK cells, many were VEGFA− (56% at gd7; 55% at gd9 and 70% at gd14). Thus, DBA+ uNK cells are a mixed population of cells with <50% having detectable VEGFA expression. Dual label IHC also established that DBA+ uNK cells, known to express PRF1 or VEGFA, can simultaneously express both of these proteins (Fig. 4E). Thus, potentially angiogenic DBA+VEFGA+ uNK cells retain immunological capacity.

Expression of RAS components at mid gestation

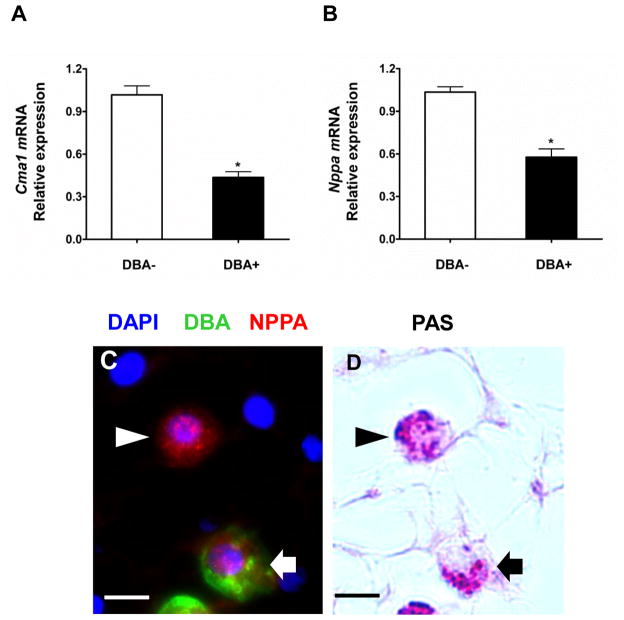

Transcripts for Ren1 (the enzyme cleaving AGT to ANGI), Ace, Cma1 (two enzymes cleaving angiotensin I to vasoactive angiotensin II), Nppa and Agtr2 were detected in lystates of whole decidua (data not shown) and of uNK cells (Fig. 5 and 6) from midpregnancy. Agt, Agtr1 and Agtr2 were detected in lystates of whole decidua from midpregnancy but were not detected in either DBA− or DBA+ gd10 uNK cells (Supplementary Fig. 1C).

Figure 5. Expression of Cma1 and NPPA by gd10.5 uNK cells.

Relative mRNA expression by DBA− and DBA+ gd10 CD3E-IL2RB+ decidual cells of (A) Cma1 and (B) Nppa using qRT-PCR normalized to Hprt expression. Data are mean±SEM from cells prepared in three independent sorting experiments. * P<0.05. (C–D) show the same microscope field with (C) a 3 color merged image showing DAPI, FITC-DBA+ uNK cells and Alexa Fluor® 594-NPPA. (D) shows post-fluorescence staining with PAS to identify all uNK cells. PAS+DBA- uNK cells show more NPPA reactivity than PAS+DBA-cells but both subsets stain. Arrowheads-PAS+DBA-cells; Arrows-PAS+DBA+ cells; Size bar (C–D) 20μm

Figure 6. Expression of REN1 and ACE by gd10.5 uNK cells.

Relative mRNA expression of Ren1 (A) and Ace (D) by sorted CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− and CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ decidual cells by qRT-PCR normalized to Hprt. Data are means±SEM from cells prepared in three independent sorting experiments. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01. (B–C) show the same microscope field with (B) a 3 color merged image showing DAPI, FITC-DBA+ uNK cells and Alexa Fluor® 594–REN1. (C) shows post-fluorescence staining with PAS to identify all uNK cells. REN1 reactivity was largely localized over uNK cells with random weaker stromal staining. (E–F) show the same microscope field from a different section showing (E) a 3 color merged image showing DAPI, FITC-DBA+ uNK cells and Alexa Fluor® 594-ACE. (F) post-fluorescence staining with PAS to identify all uNK cells. ACE expression was almost exclusively over uNK cells. Arrowheads-PAS+DBA-cells; Arrows-PAS+DBA+ cells; Size bars represent 20μm.

CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− cells had greater relative transcript abundance for Cma1 (~2.2X) (Fig. 5A). Nppa, a gene previously reported as translated in DBA+ mouse uNK cells, had relatively greater transcript abundance in CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− cells (~2X; Fig. 5B). No antibody is commercially available for IHC detection of mouse CMA1. IHC detected NPPA on PAS+DBA− uNK cells and, as previously reported, on PAS+DBA+ uNK cells (Fig. 5C, D).

CD3E-IL2RB+DBA+ cells expressed ~12X relatively more Ren1 and ~28X relatively more Ace transcripts than CD3E-IL2RB+DBA− cells (Fig. 6A, D). IHC detected REN1 (Fig. 6B, C) and ACE (Fig. 6E, F) on PAS+DBA− and PAS+DBA+ uNK cells. For REN1, reactivity was predominantly over uNK cells with minor stromal reactivity. For ACE, decidual endothelial cells were also reactive but at much lower intensity than uNK cells (Fig. 6E). Supplementary Table 1 summarizes these findings.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that, at midpregnancy, the mouse uNK cell population is comprised of at least three distinct subsets. These are DBA lectin negative uNK cells and two subsets of DBA+ uNK cells. The DBA+ uNK cell subsets arise from blood borne progenitor/precursor cells and transcribe high levels of Pgf, Ren1 and Ace. The DBA+ subsets differ in translation of VEGFA. VEGFA is readily co-localized by IHC with some DBA+ uNK cells while the other DBA+ subset is comprised of cells that show no detectable reactivity. No morphological criteria distinguish the three subsets (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Presence or absence of DBA lectin reactivity was not correlated with a difference in the genes being expressed but with relative abundance of mRNA for each gene. DBA lectin reactivity did not characterize cells with higher overall numbers of transcripts since several of the target genes investigated had dominant expression in DBA− uNK cells, for example Ifng. This finding was unexpected and suggested that the increasing tissue levels of decidual IFNG observed in various strains of mice to midpregnancy [15] result from the rapid, massive expansion and maturation [29] of less IFNG-productive, homed, DBA+ uNK cells.

While weaker IFNG producers, DBA+ uNK cells were stronger IL22 producers. Although these decidual leukocytes are regionally (mesometrially) concentrated, they do not appear to contribute to functional and structural boundaries that characterize lymphoid organs and regulate specific immune cell interactions [30;31]. This may be due to the dynamic nature of DB over pregnancy. Since DBA− and DBA+ uNK cells co- mingle (Fig. 1–6) and can be adjacent ([13], supplementary Fig. 1B), reciprocal regulatory actions between DBA− and DBA+ uNK cells cannot be excluded. The differences in relative abundance between Ifng and Il22 in the DBA− and DBA+ cell subsets and the differences in relative abundance of Ren1 and Cma1, transcripts that encode enzymes that act on a common substrate, support this possibility. Based on relative transcript abundance PAS+DBA− and PAS+DBA+ uNK cells appear to have the potential to play greater roles in processes other than immune cytokine production, the previously postulated major function for mouse uNK cells [10;13].

Assessed by relative transcript abundance, uNK cells have the potential to produce more PGF than VEGFA. Previous studies of Pgf−/− implant sites, revealed uNK cell anomalies as the major histopathology; a very high proportion of uNK cells were binucleate by gd8. Enlarged decidual areas were also present [19]. Although decidual vascular structure has not been thoroughly assessed in Pgf−/− mice, study of spiral arterial modification indicated only a slight delay in timing of this change [19]. Mouse uNK cells express receptors for the hormone prolactin-like peptide A) (PRL4A), a trophoblast (placental cell) product [32]. Others report that PRL41 regulates IFNG production by rat and mouse uNK cells [33;34] and enhances PGF and VEGF production by mouse uNK cells exposed to non ambient oxygen levels [35]. Human first trimester NCAM1bright (CD56bright) uNK cells also have greater message abundance for PGF than VEGFA (transcript hybridization intensity of 2155 versus 135 [36]). Additionally, PGF secretion is greater than VEGF secretion for human uNK cells or blood NK cells following culture in IL15 [36]. Thus, low plasma PGF levels seen in advance of pre-eclampsia [37;38] may reflect deficits in NK cell populations as well as in more widely accepted trophoblast cell functions [37].

Male et al, addressed IL22 in human uNK cells collected between 8–10 wks gestation [16]. They identified transcripts and protein production in immature (stage 3) but not in mature (stage 4) uNK cells and suggested IL22 production was aligned with steps in uNK cell maturation. About 15% of “stage 3” human uNK cells produced FACS-detectable IL22. The proportional but not the maturational data align with our findings in mice. As shown in Fig. 2, IL22 is present in heavily granulated, terminally-differentiated, mature uNK cells. The rapid changes in implantation sites during placental formation may account for this apparent interspecies difference since the human study was conducted in early pregnancy and our study at midgestation. Male et al. suggested that IL22–producing uNK cells may be important in menstrual cycle shedding and regeneration of endometrial mucosa. Presence of an IL22 producing uNK cell subset in mice, a non-menstruating species, and our ability to conclude from DBA lectin binding of IL22-producing cells that this population increases towards midgestation, suggest additional roles for IL22. NK cells expressing IL22 are present in human and mouse intestinal mucosa [39;40] where they stimulate epithelial cells to produce mitogenic and anti-apoptotic molecules [39]. Since placental trophoblasts are epithelial in origin, the IL22 dominant uNK cell subset may support survival of trophoblasts that invade decidua. DBA+IL22+ uNK cells resemble intestinal IL22+ cells because they have limited production of IFNG (Fig. 2) and produce LIF [41]. However, in contrast to intestinal IL22 producing-NK cells, DBA+ uNK cells express perforin and granzyme [39;40;42] (Fig. 4) and do not have IL7R (CD127) expression until fully mature (onsets in some gd10 uNK cells [43;44]). While Cella et al. [39] propose that intestinal IL22 producing NK cells arise locally, our adoptive transfer data clearly show that DBA+IL22+ uNK cells arise from circulating cells. Whether DBA− uNK cells are related to or represent a type of LTI or ILC as defined in other organs will require further studies that address additional markers characteristic of these lineages.

A number of reports suggest that hypertension has an immune basis [45], including studies of pre-eclamptic women in which circulating Th17 cells do not decline in 3rd trimester [23]. This finding predicts reduced IL22 production by uNK cells. Our data indicate that uNK cells have the potential for RAS-based input to circulatory regulation with DBA+ uNK cells having more potential to cleave AGT and angiotensin I. DBA− cells are more likely to use CMA1 in this process and to antagonize AGTR1 signaling via NPPA. This is the first report of uNK cell subsets differing in RAS transcripts. The finding of absence of Agtr1 and Agtr2 transcripts in uNK cells immunoreactive for these gene products requires further study but may reflect rapid changes in gene expression that occur in implantation sites [46]. Absence of Agt transcripts was unexpected, given their detection in human blood NK cells [22]. Detection of Agt transcripts in decidual tissue suggests however that substrate would be available to uNK cell-produced RAS enzymes. While it is appealing to postulate that RAS expression by uNK cells contributes to blood pressure regulation and intravital video-recordings of drug agonist challenge have shown that NK cells promote constriction of skeletal microvessels (cremaster circulation) [47], other roles must be considered. RAS members are involved in anti-inflammatory, inflammatory and fibrotic processes, in development including regulation of VEGFA, insulin-like growth factor and chemokine production, in tissue homeostasis and wound healing and in intestinal smooth muscle contraction [48]. The extent to which lymphocytes contribute to systemic or uteroplacental RAS concentrations is undefined, making the overall importance of the immune cell source unclear [49]. However, circulating antibodies to AGTR1 are associated with pre-eclampsia in humans [50] and in mouse models displaying hypertensive pregnancies [51].

These studies are the first to document that DBA+ mouse uNK cells differ in functional potential from DBA− mouse uNK cells. Because our findings were consistent between randombred and MHC-distinct inbred strains, they suggest a generalized pattern associated with decidual development. This is important since DBA lection-based identification of uNK cells has widely replaced PAS staining and is considered to provide unbiased uNK cell population information. Skewing of transcripts between DBA− and DBA+ uNK cells was demonstrated in three distinct product areas; cytokines, angiogenic factors and RAS components. Heterogeneity was independent of uNK cell maturity (ie. diameter and number of cytoplasmic granules) since all stages of maturation are present as DBA− and DBA+ cells. DBA− cells were a subset with high IFNG production while the DBA+ cells had the potential to produce more IL22, an IL10-related molecule. Thus, introduction of the terms mouse uNK1 and uNK2 for DBA− and DBA+ uNK cells may be appropriate in analogy with Th subsets. That, however, would emphasize differences in production of cytokines rather than differences in production of angiogenic and vasoregulatory factors which appear to be stronger potential roles for uNK cells. Understanding the transcriptional or epigenetic mechanisms that promote uNK cell heterogeneity will be a key advance as will determining whether an imbalance between uNK cell subsets could significantly impact pregnancy outcomes [52;53].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Allison Felker, Alexander Hofmann and Dr. Elly Sanchez for technical assistance.

Additional abbreviations

- DB

decidua basalis

- DBA

Dolichos biflorus agglutinin

- gd

gestation day

- MLAp

mesometrial lymphoid aggregate of pregnancy

- PAS

Periodic Acid Schiff’s

- RAS

renin angiotensin system

- u

uterine

Footnotes

These studies were supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Canada and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (BAC); MRC UK (FC); Brazilian Federal Agency for Support of Graduate Education (CAPES) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (ATY). JHZ was supported by a Province of Ontario Postdoctoral Fellowship, PDAL by a Sandwich Doctoral Training award from CNPq and BAC by the Canada Research Chairs Program.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Reference List

- 1.Cherrier M, Ohnmacht C, Cording S, Eberl G. Development and function of intestinal innate lymphoid cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:227–283. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croy BA, van den Heuvel MJ, Borzychowski AM, Tayade C. Uterine natural killer cells: a specialized differentiation regulated by ovarian hormones. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:161–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peel S. Granulated metrial gland cells. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1989;115:1–112. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paffaro VA, Jr, Bizinotto MC, Joazeiro PP, Yamada AT. Subset classification of mouse uterine natural killer cells by DBA lectin reactivity. Placenta. 2003;24:479–488. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parr EL, Young LH, Parr MB, Young JD. Granulated metrial gland cells of pregnant mouse uterus are natural killer-like cells that contain perforin and serine esterases. J Immunol. 1990;145:2365–2372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones RK, Searle RF, Stewart JA, Turner S, Bulmer JN. Apoptosis, bcl-2 expression, and proliferative activity in human endometrial stroma and endometrial granulated lymphocytes. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:995–1002. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.4.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delgado SR, McBey BA, Yamashiro S, Fujita J, Kiso Y, Croy BA. Accounting for the peripartum loss of granulated metrial gland cells, a natural killer cell population, from the pregnant mouse uterus. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:262–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulmer JN, Lash GE. Human uterine natural killer cells: a reappraisal. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:511–521. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hazan AD, Smith SD, Jones RL, Whittle W, Lye SJ, Dunk CE. Vascular-leukocyte interactions. Mechanisms of human decidual spiral artery remodeling in vitro. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1017–1030. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashkar AA, di Santo JP, Croy BA. Interferon gamma contributes to initiation of uterine vascular modification, decidual integrity, and uterine natural killer cell maturation during normal murine pregnancy. J Exp Med. 2000;192:259–270. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li XF, Charnock-Jones DS, Zhang E, Hiby S, Malik S, Day K, Licence D, Bowen JM, Gardner L, King A, Loke YW, Smith SK. Angiogenic growth factor messenger ribonucleic acids in uterine natural killer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1823–1834. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito S, Kasahara T, Sakakura S, Enomoto M, Umekage H, Harada N, Morii T, Nishikawa K, Narita N, Ichijo M. Interleukin-8 production by CD16-CD56bright natural killer cells in the human early pregnancy decidua. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200:378–383. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang JH, Yamada AT, Croy BA. DBA-lectin reactivity defines natural killer cells that have homed to mouse decidua. Placenta. 2009;30:968–973. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yadi H, Burke S, Madeja Z, Hemberger M, Moffett A, Colucci F. Unique receptor repertoire in mouse uterine NK cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:6140–6147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashkar AA, Croy BA. Interferon-gamma contributes to the normalcy of murine pregnancy. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:493–502. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Male V, Hughes T, McClory S, Colucci F, Caligiuri MA, Moffett A. Immature NK cells, capable of producing IL-22, are present in human uterine mucosa. J Immunol. 2010;185:3913–3918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.di Santo JP, Vosshenrich CA, Satoh-Takayama N. A ‘natural’ way to provide innate mucosal immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neufert C, Pickert G, Zheng Y, Wittkopf N, Warntjen M, Nikolaev A, Ouyang W, Neurath MF, Becker C. Activation of epithelial STAT3 regulates intestinal homeostasis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:652–655. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.4.10615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tayade C, Hilchie D, He H, Fang Y, Moons L, Carmeliet P, Foster RA, Croy BA. Genetic deletion of placenta growth factor in mice alters uterine NK cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4267–4275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C, Tanaka T, Nakamura H, Umesaki N, Hirai K, Ishiko O, Ogita S, Kaneda K. Granulated metrial gland cells in the murine uterus: localization, kinetics, and the functional role in angiogenesis during pregnancy. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;60:420–429. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jurewicz M, McDermott DH, Sechler JM, Tinckam K, Takakura A, Carpenter CB, Milford E, Abdi R. Human T and natural killer cells possess a functional renin-angiotensin system: further mechanisms of angiotensin II-induced inflammation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1093–1102. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006070707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santner-Nanan B, Peek MJ, Khanam R, Richarts L, Zhu E, Fazekas de St GB, Nanan R. Systemic increase in the ratio between Foxp3+ and IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells in healthy pregnancy but not in preeclampsia. J Immunol. 2009;183:7023–7030. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stetson DB, Mohrs M, Reinhardt RL, Baron JL, Wang ZE, Gapin L, Kronenberg M, Locksley RM. Constitutive cytokine mRNAs mark natural killer (NK) and NK T cells poised for rapid effector function. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1069–1076. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Croy BA, Zhang J, Tayade C, Colucci F, Yadi H, Yamada AT. Analysis of uterine natural killer cells in mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;612:465–503. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-362-6_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatta K, Carter AL, Chen Z, Leno-Duran E, Ruiz-Ruiz C, Olivares EG, Tse Y, Pang SC, Croy BA. Dynamic expression of the vasoactive proteins Agtr1, Agtr2 and Nppa by mouse uterine Natural Killer cells. Reprod Sci. 2011;18:383–390. doi: 10.1177/1933719110385136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prophet EB, Mills B, Arrington JB, Sobin LH, editors. AFIP Laboratory Methods in Histotechnology. Washington, D.C: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, American Registry of Pathology; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z, Ohno N, Terada N, Zhou D, Yoshimura A, Ohno S. Application of periodic acid-Schiff fluorescence emission for immunohistochemistry of living mouse renal glomeruli by an “in vivo cryotechnique”. Arch Histol Cytol. 2006;69:147–161. doi: 10.1679/aohc.69.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tayade C, Fang Y, Black GP, AP, Erlebacher A, Croy BA. Differential transcription of Eomes and T-bet during maturation of mouse uterine natural killer cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1347–1355. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0305142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mueller SN, Germain RN. Stromal cell contributions to the homeostasis and functionality of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:618–629. doi: 10.1038/nri2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwickert TA, Victora GD, Fooksman DR, Kamphorst AO, Mugnier MR, Gitlin AD, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. A dynamic T cell-limited checkpoint regulates affinity-dependent B cell entry into the germinal center. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1243–1252. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller H, Liu B, Croy BA, Head JR, Hunt JS, Dai G, Soares MJ. Uterine natural killer cells are targets for a trophoblast cell-specific cytokine, prolactin-like protein A. Endocrinology. 1999;140:2711–2720. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.6.6828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ain R, Tash JS, Soares MJ. Prolactin-like protein-A is a functional modulator of natural killer cells at the maternal-fetal interface. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;204:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ain R, Dai G, Dunmore JH, Godwin AR, Soares MJ. A prolactin family paralog regulates reproductive adaptations to a physiological stressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16543–16548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406185101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroger C, Vijayaraj P, Reuter U, Windoffer R, Simmons D, Heukamp L, Leube R, Magin TM. Placental vasculogenesis is regulated by keratin-mediated hyperoxia in murine decidual tissues. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1578–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanna J, Goldman-Wohl D, Hamani Y, Avraham I, Greenfield C, Natanson-Yaron S, Prus D, Cohen-Daniel L, Arnon TI, Manaster I, Gazit R, Yutkin V, Benharroch D, Porgador A, Keshet E, Yagel S, Mandelboim O. Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat Med. 2006;12:1065–1074. doi: 10.1038/nm1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang M, Mukherjea D, Gobble RM, Groesch KA, Torry RJ, Torry DS. Glial cell missing 1 regulates placental growth factor (PGF) gene transcription in human trophoblast. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:841–851. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.065599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romero R, Nien JK, Espinoza J, Todem D, Fu W, Chung H, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, Erez O, Mazaki-Tovi S, Gomez R, Edwin S, Chaiworapongsa T, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. A longitudinal study of angiogenic (placental growth factor) and anti-angiogenic (soluble endoglin and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1) factors in normal pregnancy and patients destined to develop preeclampsia and deliver a small for gestational age neonate. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:9–23. doi: 10.1080/14767050701830480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cella M, Fuchs A, Vermi W, Facchetti F, Otero K, Lennerz JK, Doherty JM, Mills JC, Colonna M. A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature. 2009;457:722–725. doi: 10.1038/nature07537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satoh-Takayama N, Vosshenrich CA, Lesjean-Pottier S, Sawa S, Lochner M, Rattis F, Mention JJ, Thiam K, Cerf-Bensussan N, Mandelboim O, Eberl G, di Santo JP. Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46+ cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity. 2008;29:958–970. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Croy BA, Guilbert LJ, Browne MA, Gough NM, Stinchcomb DT, Reed N, Wegmann TG. Characterization of cytokine production by the metrial gland and granulated metrial gland cells. J Reprod Immunol. 1991;19:149–166. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(91)90014-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lima PDA, Degaki KY, Tayade C, Croy BA, Yamada AT. Heterogeneity in composition of mouse uterine Natural Killer cell granules. J Leukoc Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1189/jlb.0312136. Epub May 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J, Chen Z, Fritz JH, Rochman Y, Leonard WJ, Gommerman JL, Plumb AW, Abraham N, Croy BA. Unusual timing of CD127 expression by mouse uterine natural killer cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91:417–426. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1011501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burke SD, Barrette VF, Gravel J, Carter A, Hatta K, Zhang J, Chen Z, Leno-Duran E, Bianco J, Leonard S, Murrant C, Adams MA, Croy BA. Uterine NK cells, spiral artery modification and the regulation of blood pressure during mouse pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:472–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, Madhur MS, Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Vinh A, Weyand CM. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:132–140. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gu Y, Srivastava RK, Clarke DL, Linzer DI, Gibori G. The decidual prolactin receptor and its regulation by decidua-derived factors. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4878–4885. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.11.8895360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leonard S, Croy BA, Murrant CL. Arteriolar reactivity in lymphocyte-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1276–H1285. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00346.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garg M, Angus PW, Burrell LM, Herath C, Gibson PR, Lubel JS. Review article: the pathophysiological roles of the renin-angiotensin system in the gastrointestinal tract. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:414–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anton L, Merrill DC, Neves LA, Diz DI, Corthorn J, Valdes G, Stovall K, Gallagher PE, Moorefield C, Gruver C, Brosnihan KB. The uterine placental bed Renin-Angiotensin system in normal and preeclamptic pregnancy. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4316–4325. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herse F, Verlohren S, Wenzel K, Pape J, Muller DN, Modrow S, Wallukat G, Luft FC, Redman CW, Dechend R. Prevalence of agonistic autoantibodies against the angiotensin II type 1 receptor and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 in a gestational age-matched case study. Hypertension. 2009;53:393–398. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.124115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou CC, Zhang Y, Irani RA, Zhang H, Mi T, Popek EJ, Hicks MJ, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibodies induce pre-eclampsia in pregnant mice. Nat Med. 2008;14:855–862. doi: 10.1038/nm.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quenby S, Farquharson R. Uterine natural killer cells, implantation failure and recurrent miscarriage. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;13:24–28. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)62012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiby SE, Regan L, Lo W, Farrell L, Carrington M, Moffett A. Association of maternal killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors and parental HLA-C genotypes with recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:972–976. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.