Abstract

The commercial cultivation of genetically engineered (GE) crops in Europe has met with considerable consumer resistance, which has led to vigorous safety assessments including the measurement of substantial equivalence between the GE and parent lines. This necessitates the identification and quantification of significant changes to the metabolome and proteome in the GE crop. In this study, the quantitative proteomic analysis of tomato fruit from lines that have been transformed with the carotenogenic gene phytoene synthase-1 (Psy-1), in the sense and antisense orientations, in comparison with a non-transformed, parental line is described. Multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT), with tandem mass spectrometry, has been used to identify proteins, while quantification has been carried out with isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ). Fruit from the GE plants showed significant alterations to their proteomes compared with the parental line, especially those from the Psy-1 sense transformants. These results demonstrate that MudPIT and iTRAQ are suitable techniques for the verification of substantial equivalence of the proteome in GE crops.

Key words: Genetic modification, mass spectrometry, multidimensional liquid chromatography, phytoene synthase, proteomics, Solanum lycopersicum

Introduction

The use of genetic engineering to alter the traits of crop plants is well established and is of major biotechnological interest (Moose and Mumm, 2008; Sidhu and Chellan, 2010). Following the commercial introduction of crop plants such as Roundup Ready soya in 1996 and corn in 1998, the so-called second generation of genetically engineered (GE) crops is primarily aimed at improving the nutrient status of crop plants for the consumer (reviewed by Mattoo et al., 2010; McGloughlin, 2010). For example, Golden Rice contains β-carotene (pro-vitamin A), with the aim of alleviating its deficiency in developing countries (Potrykus, 2001), while tomato has been transformed with a number of carotenoid genes to increase levels of lycopene (Fraser et al., 2002) and β-carotene (Romer et al., 2000). The genetic engineering of plants has also been a valuable tool in perturbing metabolic pathways in order to understand potential pathway cross-talk and silent metabolism (Long et al., 2006; Lewinsohn and Gijzen, 2009), and to discover regulatory steps (e.g. Fraser et al., 2002; Millar et al., 2007).

Despite these technological advances, the commercial use of GE crops has been controversial, especially with consumer resistance in Europe (Rommens, 2010), leading to the need for food safety assessment of GE crops, including the concept of substantial equivalence (OECD, 2006). This necessitates the identification of unintended changes to the plant due to the genetic modification, as opposed to those that occur as a consequence of environmental or intervariety variations. Whilst DNA-based approaches are favoured for the detection of transgenes, the application of omic platforms to identify phenotypic changes and bring a holistic approach to the analyses has been recommended, to include metabolomics and proteomics (Trojanowicz et al., 2010; Ricroch et al., 2011).

In this study, the proteomic analysis of GE and non-GE tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) lines using multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT) with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) is reported. Quantification of proteins has been carried out using iTRAQ (isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification), which represents a significant advancement in protein quantification by MS (Ross et al., 2004). iTRAQ uses four identical chemical tags, with the same overall mass, to multiplex four samples for relative peptide quantification. When iTRAQ-labelled peptides are fragmented using MS, peaks from singly charged reporter group fragments appear in the m/z range of 114, 115, 116, and 117. Peptides are quantified by interpretation of the ratios of these fragment peaks (Boehm et al., 2007).

The GE tomatoes used in this study have been transformed with the tomato phytoene synthase-1 gene (Psy-1) in the sense (Fraser et al., 2007) and antisense orientations (Bramley et al., 1992). Psy-1 encodes the fruit-specific enzyme phytoene synthase, which catalyses the first step in carotenoid biosynthesis (Bramley, 2002). This reaction is thought to be the prime regulatory step in carotenogenesis (Fraser et al., 2002). The Psy-1 sense lines show pleiotropic effects (Fray et al., 1995), including elevated carotenoid levels (Fraser et al., 2007). The latter were used in the present investigation. The antisense lines produce fruit devoid of carotenoids, due to the down-regulation of phytoene synthase (Bramley et al., 1992). Included in the investigation are the wild-type parent of both transgenic lines cv Ailsa Craig, and also a line produced during the transformation of Alisa Craig that did not inherit the transgene in the second generation (referred to as the azygous line) and shows a wild-type carotenoid phenotype, which has been through transformation but did not retain the transgene in the second generation. Thus, all lines are from the same genetic background and the azygous control allows the identification of any proteomic changes due to the transformation protocol rather than integration of the Psy-1 transgene, in either orientation.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

The wild-type tomato cultivar was S. lycopersicum Mill cv Alisa Craig. Transgenic lines were produced from this cultivar. The Psy-1 antisense line was from an earlier study (Bramley et al., 1992), as was the Psy-1 constitutively expressing (sense) line (Fraser et al., 2007). The azygous line was from the latter investigation. All plants were grown in randomized plots in the glasshouse with supplementary lighting of 110 µmol m–2 s–1 provided by 400W Son-T high pressure sodium bulbs (Osram Ltd, Berkshire, UK). A light/dark cycle of 16/8h was maintained. Fruit were harvested at 7 d post-breaker, at the same time of day. Four plants of each line were grown, and three fruit from each plant were pooled for analyses. Pooled fruit were immediately chopped, deseeded, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then freeze-dried prior to protein extraction.

Preparation of protein extracts

Triplicate samples of tomato powders (20mg) were extracted with 7M urea, 2M thiourea, 2% CHAPS, 50mM TRIS-HCl, pH 8 (500 µl) at room temperature for 30min. Extracts were centrifuged at 14 000 g for 10min and the supernatant collected. Ice-cold acetone (2.5ml) was added and the mixture left at –20 °C overnight. Extracts were then centrifuged at 14 000 g for 10min and the supernatant discarded. Pellets were washed three times with ice-cold acetone and dried in a vacuum centrifuge (Genevac SP Scientific, Ipswich, Suffolk, UK). They were resuspended in 10 vols of 10mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) buffer (pH 8.5) and protein concentrations determined by a Bradford assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, UK), with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard. Protein aliquots (100 µl) were collected, dried in a vacuum centrifuge, and stored at –80 °C prior to analysis.

Proteolytic in-solution digestion

Tomato proteins (100 µg) were reduced and alkylated using the iTRAQ kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Solutions in 10mM TEAB buffer (100 µl) were digested with trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) at a protein:trypsin ratio of between 1:100 and 1:1000 (v/v). The digests were incubated at 37 °C overnight. Following digestion, tubes were placed at –20 °C before adding the iTRAQ labelling reagent.

Isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) labelling

Aliquots of digested tomato fruit (100 µg of protein) were labelled with four multiplex iTRAQ reagents according to the manufacturer’s instructions, except that double the quantity of labelling substrate was used to ensure complete labelling of the peptides (see the Results and Discussion). Additionally, washes of the precipitated protein were increased from two to three. In order to avoid bias from one tag, experiments were designed so that each line was labelled in rotation with each of the four tags, as shown in Supplementary Table S1 available at JXB online. Following labelling, aliquots were pooled for strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatographic separation.

Strong cation exchange fractionation

The iTRAQ-labelled peptides were fractionated off-line using an SCX resin prior to nano C18 reverse phase liquid chromatography (nano LC). Peptide separations were performed with PolySULFOETHYL A (Applied Biosystems). Loading buffer [100 µl; 10mM K2HPO4:acetonitrile 75:25 (v/v), pH 3] was added to trypsin digests and balanced to pH 3 by H3PO3. SCX cartridges were conditioned with loading buffer. Peptide digests (pH 3) were separated using a stepped mobile phase gradient [50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 500mM K2HPO4:acetonitrile 75:25 (v/v), pH 3] and the eluate collected from each fraction (1ml). Fractions were dried in a Genevac EZ-2 Evaporator vacuum centrifuge and stored at –20 °C.

Nano liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

Nano-LC electrospray ionization (ESI) MS/MS experiments were performed on two machines: a QSTAR Pulsar I (Applied Biosystems) hybrid quadrupole time of flight (TOF) mass spectrometer and an Agilent QTof 6520 mass spectrometer hybrid quadrupole TOF mass spectrometer. With the former, the mass spectrometer was connected to a nano LC system (LC Packings, Camberley, UK). The sample injection order was randomized using Excel to avoid bias, and each sample was injected twice. Samples were loaded onto a 200 µm i.d.×5mm PS-DVB monolithic (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) trap column with a flow rate of 10 µl min–1 of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) for 30min. After pre-concentration, the trap column was automatically switched in-line with the PS-DVB monolithic (3 µm, 100 µm i.d.×50mm, Dionex) analytical column and the peptides eluted with a linear gradient starting at 95% eluent A [0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water] to 40% eluent B [0.1% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile] at 40min, the flow rate being 300 nl min–1. HPLC fractions of tryptic peptides were injected using an LC Packings FAMOS autosampler and UltiMate LC pumps. A Protana nanospray interface and 10 µm distal coated fused silica PicoTips (New Objective, Woburn, MA, USA) were used for the nano ESI.

The positive TOF mass spectra were recorded using information-dependent acquisition (IDA). TOF MS survey scans were recorded for mass range m/z 400–1600, followed by MS/MS scans of the two most intense peaks. Typical ion spray voltage was in the range of 2.0–2.4kV, and N2 was used as the collision gas. Other source parameters and spray positions were optimized with the tryptic digest of BSA. Analyst QS 1.0 sp8 software from Applied Biosystems was employed for data analysis.

The Agilent QTof 6520 mass spectrometer hybrid quadrupole TOF mass spectrometer was connected to an Agilent 1200 nano LC (Agilent, Wokingham, UK) system. Cation exchange fractions of 50, 100, and 150mM were resuspended in 1% (v/v) formic acid (50 µl). Due to the amount of salt present, the 500mM samples were resuspended with 75 µl of 1% (v/v) formic acid. A 10 µl injection was loaded onto a Agilent Chip Cube trap column with a flow rate of 4 µl min–1 of 0.1% (v/v) TFA, for 5min. Chromatographic separations were made using the Agilent Chip Cube [Large Capacity Chip (II) G4240-62010; separation, 150 mm×75 µM; enrichment, 9mm 160 nl, Zorbax 300SB-C18 5 µM). An isocratic gradient, with a flow rate of 0.3 µl min–1 of solvent A (0.1% formamide in H2O) for 3min followed by a linear gradient from 5% to 45% solvent B (0.1% formamide in 90% acetonitrile) for 128min was used. Positive TOF mass spectra were recorded using IDA. TOF MS survey scans were recorded for mass range m/z 400–1600 every 200ms, followed by MS/MS scans of the four most intense peaks every 250ms. RAW files were extracted with Protein Hunter software (Agilent) into Mascot generic files (.mgf) prior to merging and analysis by Mascot v 2.3 (Matrix Science) to generate iTRAQ and identification data. Protein Pilot (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA) was used to identify peptide modifications.

Identification and functionality of proteins

Proteins were identified through Mascot v 2.3 (Matrix Science, London, UK) and the Molspec-ID Online Database (MSDB) of viridiplantae. They were classified through interrogation of Swiss-Prot (http://web.expasy.org/groups/swissprot/), with enzymic functions obtained from KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) and PlantCyc (http://plantcyc.org/).

Statistical methods and multivariate data analysis

Multivariate data analysis was performed with SIMCA software (version 12, Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden). Principal component analysis (PCA) was also carried out to detect outliers. The supervised method, partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), was used on data sets to identify which variables were responsible for sample classification. The Student’s t-test and correlation analyses were performed using Excel.

Results and Discussion

Optimization of workflow

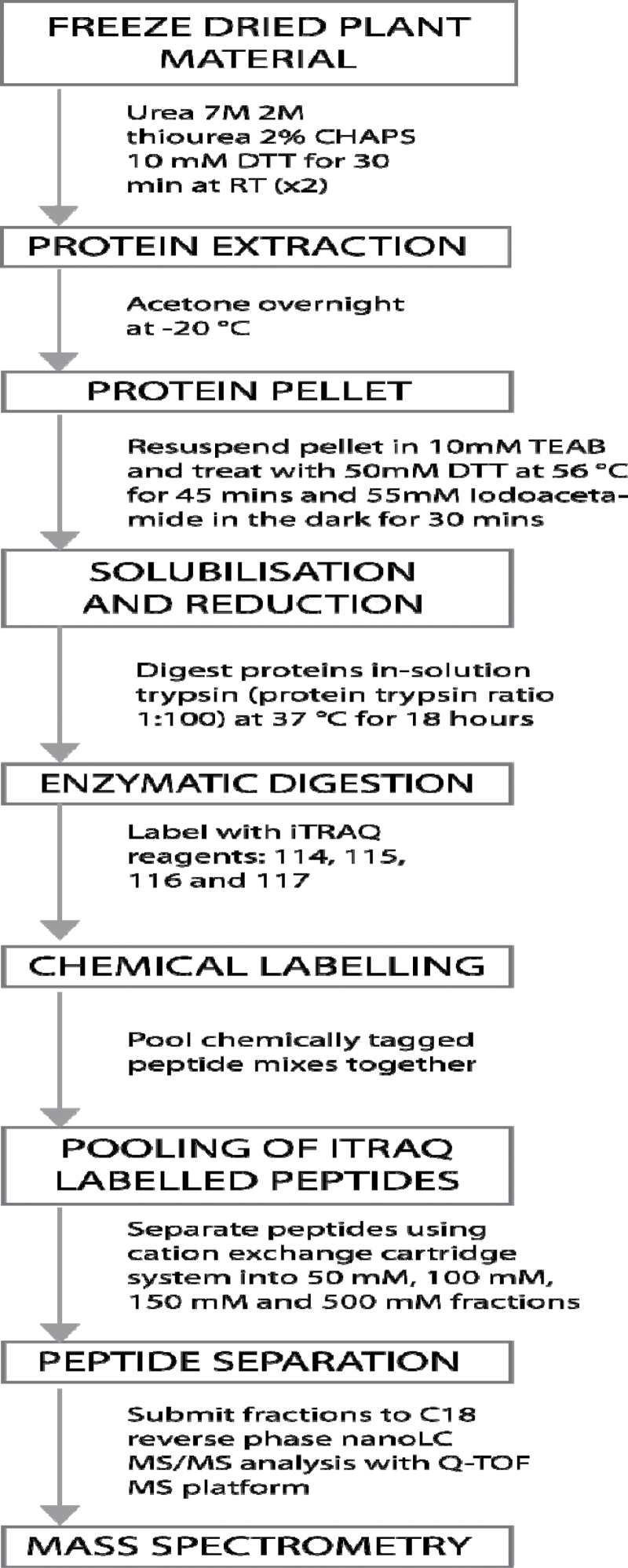

A typical elution profile of tryptic digests from a PolySULFOETHYL A 5µm cation exchange resin, off-line, is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online. Initial iTRAQ labelling studies followed the manufacturer’s instructions, but resulted in incomplete labelling of the tomato peptides (data not shown). However, doubling the quantity of labelling reagent and increasing the number of washes of the precipitated protein increased yield from 85% to 98%, and resulted in complete labelling of peptides (Supplementary Fig. S2). This underestimation has been reported elsewhere for animal tissues (Ow et al., 2009; Karp et al., 2010). A typical product ion mass spectrum of an iTRAQ-labelled peptide is shown in Supplementary Fig. S3, with a regression analysis for calibration shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. Four identical samples of Alisa Craig wild-type fruit were labelled with 114.1, 115.1, 116.1, and 117.1 reagents and the sets were repeated three times. There were no major differences between labels or the sample sets prepared on different days, indicating that the labelling procedure is reproducible and unbiased (data not shown). Peptide samples from the Psy-1 sense fruit were diluted 2-, 20-, and 40-fold, and labelled with the four iTRAQreagents. The experiment was repeated three times. Although the 40-fold dilution could be quantified, the coefficient of variance was high at 63.3. Dilutions of 2-fold and 20-fold reproducibly gave values of 0.47–0.65 and 0.061–0.088, respectively, compared with the expected amounts of 0.5 and 0.05. The accuracy of iTRAQ labelling, using the modified protocol, is demonstrated in Table 1, which shows labelled peptides from the Ailsa Craig acid β-fructofuranosidase, with a confidence of 99%, analysed by Protein Pilot. The complete work flow is outlined in Fig. 1. A previous study by Karp and co-workers (2010) also reported problems with the precision and accuracy of iTRAQ, experiencing poor signal data with low abumdamcne proteins, as found here. They concluded that ratio compression arises from contamination during precursor ion selection. A promising alternative procedure using multistage MS3-based scans eliminates this interference (Ting et al., 2011).

Table 1.

A comparison between different peptides from acid β-fructofuranosidase labelled with iTRAQ reagents

| Sequence of peptide | Confidence (%) | Ratio 115:114 |

|---|---|---|

| ASLDDNKQDHYAITYDLGK | 99 | 0.478 |

| GNPVLVPPPGIGVK | 99 | 0.497 |

| LLVDHSIVESFAQGGR | 99 | 0.641 |

Calculated using ProteinPilot. The mean value of ratios is 0.538.

Fig. 1.

Workflow for identification and quantification of iTRAQ-labelled peptides from tomato.

Changes to the proteomes of GE and non-GE tomato lines compared with the wild type

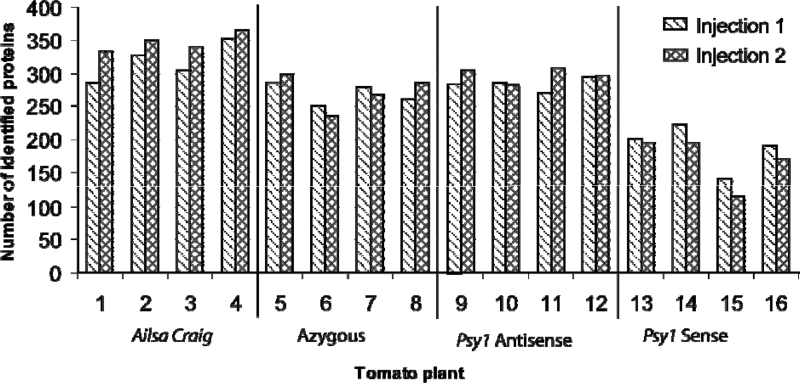

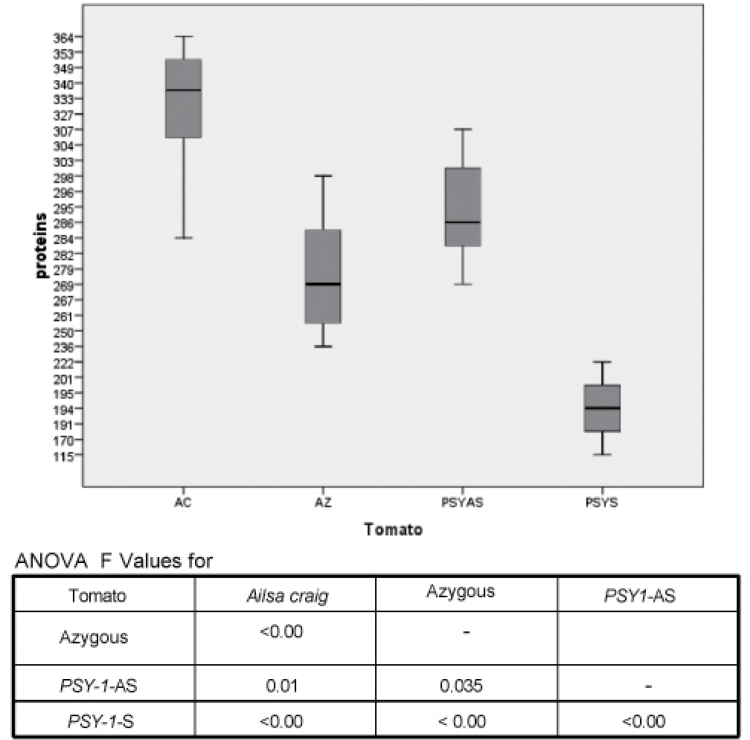

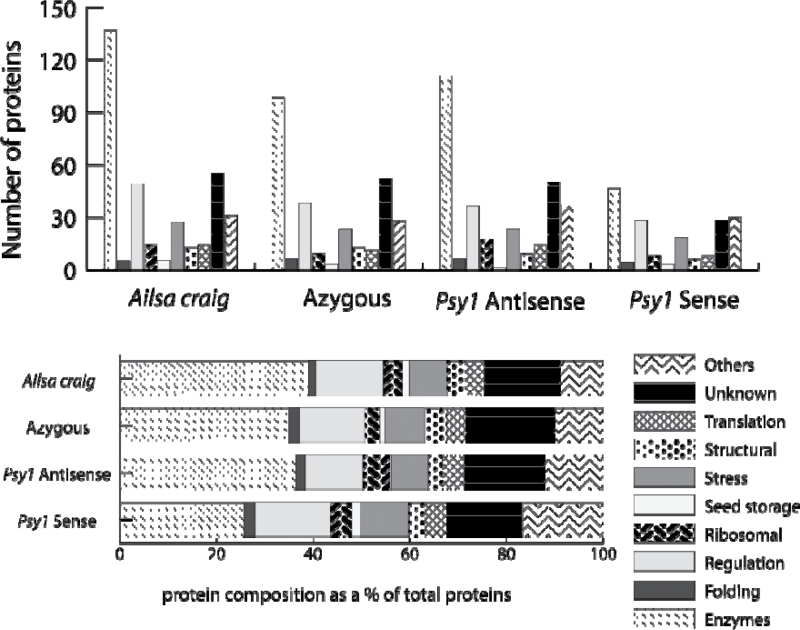

Using the workflow outlined in Fig. 1, 20 separate iTRAQ experiments were carried out to compare the protein contents, both qualitatively and quantitatively, of the four lines of tomato, as well as variation between plants of the same cultivar (Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online). In each case, two technical samples and four biological replicates were analysed. The technical replicates were not significantly different from each other, as analysed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Fig. 2). Similarly, there were no significant differences between the number of peptides of fruits from plants of the same cultivar (F-values of 0.05, 0.0052, 0.834, and 0.03 for Ailsa Craig, azygous, Psy-1 antisense, and Psy-1 sense, respectively; Fig, 2). However, the total number of proteins identified did differ significantly between the lines, in comparison with the Ailsa Craig wild type, as shown in the box whisker plot (Fig. 3). The interline ANOVA shows that, when compared with Ailsa Craig, all F-values were <0.01 The categories of the protein identified for each of the four lines, with their numbers, are shown in Fig. 4. Individual proteins showing significant changes in levels compared with the Ailsa Craig parent are listed in Table 2, whilst all the proteins identified are given in Supplementary Table S2.

Fig. 2.

Technical and biological replicates of proteins identified in each tomato cultivar. Each sample was injected twice (injection 1 and 2), whilst four biological replicates were analysed from each cultivar (1–4, 5–8, 9–12, and 13–16). Using ANOVA, there were no significant differences between injections 1 and 2 for each line, nor for intraplant variability (F > 0.05)

Fig. 3.

Box whisker plots displaying the ANOVA values of proteins from the four lines characterized in the iTRAQ experiments.

Fig. 4.

Categories and numbers of proteins identified in tomato lines.

Table 2.

Functional status and role of proteins identified as statistically different from the wild-type cultivar by the Student’s t-test

| Protein | Ratio of the line to Ailsa Craig | Fold change | Function/category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azygous | |||

| 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase 1 | 0.42 | 2.35 decrease | Enzyme |

| Disulphide-isomerase precursor-like protein | 0.47 | 2.14 decrease | Enzyme |

| Peptide methionine sulphoxide reductase | 0.45 | 2.24 decrease | Enzyme |

| Plastid isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase | 0.47 | 2.15 decrease | Enzyme |

| Vacuolar H+-ATPase A1 subunit isoform | 0.18 | 5.71 decrease | Enzyme |

| Dihydrolipoyllysine-residue succinyl transferase component of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex | 0.24 | 4.19 decrease | Enzyme |

| Psy-1 antisense | |||

| Calmodulin | 0.7 | 1.43 decrease | Calcium binding |

| Elongation factor EF-2 | 0.74 | 1.34 decrease | Translation |

| Remorin 1 | 0.7 | 1.42 decrease | Membrane protein |

| Small heat shock protein | 0.78 | 1.28 decrease | Stress |

| Small heat shock protein, chloroplastic | 0.73 | 1.37 decrease | Stress |

| Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase | 0.62 | 1.61 decrease | Enzyme |

| Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, putative | 0.46 | 2.18 decrease | Enzyme |

| Em protein | 0.52 | 1.91 decrease | Seed storage |

| Em-like protein | 0.42 | 2.37 decrease | Seed storage |

| Oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 2, chloroplastic | 0.42 | 2.39 decrease | Regulation |

| 14-3-3-like protein D | 0.41 | 2.42 decrease | Regulation |

| Psy-1 sense | |||

| Abscisic stress-ripening protein 1 | 1.16 | 1.19 increase | Stress |

| 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase | 0.64 | 1.56 decrease | Enzyme |

| Cytosolic nucleoside diphosphate kinase | 0.67 | 1.49 decrease | Enzyme |

| Dehydroascorbate reductase | 0.66 | 1.52 decrease | Enzyme |

| Disulphide-isomerase precursor-like protein | 0.65 | 1.54 decrease | Enzyme |

| Glutaredoxin | 0.82 | 1.21 decrease | Enzyme |

| Protein phosphatase 2C | 0.65 | 1.53 decrease | Enzyme |

| Thioredoxin peroxidase 1 | 0.76 | 1.32 decrease | Enzyme |

| Wound-induced proteinase inhibitor 1 | 0.67 | 1.48 decrease | Regulation |

| 28kDa Ribonucleoprotein, chloroplastic | 0.68 | 1.46 decrease | Ribosomal |

| Acidic ribosomal protein P1a-like | 0.6 | 1.65 decrease | Ribosomal |

| Chaperonin 21 precursor | 0.74 | 1.35 decrease | Folding |

| Elongation factor 1-alpha | 0.7 | 1.43 decrease | Translational elongation |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A | 0.62 | 1.61 decrease | Translational elongation |

| Late embryogenesis (Lea)-like protein | 0.63 | 1.6 decrease | Stress |

| Oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 1, chloroplastic | 0.63 | 1.58 decrease | Regulation |

| Ran-binding protein-1 | 0.66 | 1.51 decrease | |

| Remorin 1 | 0.8 | 1.26 decrease | Membrane protein |

| Ribosomal protein L12-1a | 0.64 | 1.57 decrease | Ribosome |

| Translationally controlled tumour protein homologue | 0.62 | 1.6 decrease | Calcium binding |

| 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase 1 | 0.49 | 2.06 decrease | Enzyme |

| 2-Isopropylmalate synthase A | 0.48 | 2.1 decrease | Enzyme |

| Acid beta-fructofuranosidase | 0.57 | 1.75 decrease | Enzyme |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase 2 | 0.42 | 2.37 decrease | Enzyme |

| Aspartic protease | 0.52 | 1.94 decrease | Enzyme |

| ATP synthase CF1 epsilon chain | 0.53 | 1.9 decrease | Enzyme |

| Carbonic anhydrase | 0.47 | 2.14 decrease | Enzyme |

| Catalase isozyme 1 | 0.48 | 2.09 decrease | Enzyme |

| Cytosolic aconitase | 0.55 | 1.82 decrease | Enzyme |

| Enolase | 0.49 | 2.05 decrease | Enzyme |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.52 | 1.91 decrease | Enzyme |

| Ketol-acid reductoisomerase | 0.51 | 1.97 decrease | Enzyme |

| Leucine aminopeptidase 2, chloroplastic | 0.51 | 1.95 decrease | Enzyme |

| Lipoxygenase | 0.42 | 2.4 decrease | Enzyme |

| Lipoxygenase A | 0.4 | 2.5 decrease | Enzyme |

| Malate dehydrogenase | 0.52 | 1.91 decrease | Enzyme |

| Methionine synthase | 0.4 | 2.47 decrease | Enzyme |

| Mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase | 0.46 | 2.15 decrease | Enzyme |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase 2 | 0.53 | 1.89 decrease | Enzyme |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase precursor | 0.54 | 1.85 decrease | Enzyme |

| Polygalacturonase-2 | 0.45 | 2.23 decrease | Enzyme |

| S-Adenosylmethionine synthetase 1 | 0.5 | 2.01 decrease | Enzyme |

| Vicilin | 0.44 | 2.25 decrease | Allergen |

| 14-3-3 Protein | 0.55 | 1.81 decrease | Regulation |

| 60S Ribosomal protein L13 | 0.57 | 1.74 decrease | Ribosomal |

| Actin | 0.52 | 1.92 decrease | Structural |

| Chaperonin-60 beta subunit | 0.58 | 1.74 decrease | Folding |

| Class II small heat shock protein Le-HSP17.6 | 0.53 | 1.88 decrease | Stress |

| Heat shock protein | 0.43 | 2.34 decrease | Stress |

| Histone H4 | 0.53 | 1.9 decrease | Structural |

| Hsc70 | 0.54 | 1.85 decrease | Stress |

| Mitochondrial outer membrane porin of 34 kDa | 0.48 | 2.08 decrease | Structural |

| Pathogenesis-related protein P2 | 0.59 | 1.71 decrease | Stress |

| Small heat shock protein | 0.54 | 1.86 decrease | Stress |

| Translation elongation factor-1 alpha | 0.5 | 2.01 decrease | Enzyme |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase class III-like protein | 0.39 | 2.57 decrease | Enzyme |

| Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, putative | 0.39 | 2.57 decrease | Enzyme |

| Dihydrolipoyllysine-residue succinyl transferase component of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex | 0.38 | 2.66 decrease | Enzyme |

| Glucuronosyl transferase homologue, ripening-related | 0.37 | 2.67 decrease | Enzyme |

| 40S Ribosomal protein SA | 0.36 | 2.75 decrease | Ribosomal |

| Pyrophosphate-fructose 6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase β-subunit | 0.36 | 2.79 decrease | Enzyme |

| Heat shock protein 101 | 0.33 | 3.06 decrease | Stress |

| Alcohol acyl transferase | 0.32 | 3.13 decrease | Enzyme |

| UDP-glucose:protein transglucosylase-like | 0.28 | 3.61 decrease | Enzyme |

| Monodehydroascorbate reductase | 0.27 | 3.77 decrease | Enzyme |

| Phosphoglucomutase, cytoplasmic | 0.24 | 4.2 decrease | Enzyme |

| Pectin esterase/pectin esterase inhibitor U1 | 0.25 | 4 decrease | Enzyme |

| Vacuolar H+-ATPase A1 subunit isoform | 0.2 | 5.09 decrease | Enzyme |

These results show that biological variation of the proteome between fruit of the same cultivar is insignificant, but the process of transformation itself does alter the proteome from that of the parent line, as the level of proteins identified in the azygous line is lower than that of Ailsa Craig (Fig. 3), although there is a negligible difference in the protein composition as a percentage of the total protein number (Fig. 4). Further changes occur when the transgene is inherited and therefore integrated into the genome. The largest, significant quantitative changes were found in the Psy-1 sense fruit. The number of proteins identified was less than in the other three lines, and the total number of enzymes was some 10% less within the total number of proteins (Fig. 4). Only one protein, abscisic acid stress ripening protein-1 (ASR1), was increased in the Psy-1 sense fruit. This protein has zinc-dependent DNA binding and chaperone-like activity and is synthesized in response to salt and water stress and abscisic acid (Kalifa et al., 2004). The smaller number of proteins identified in Psy-1 sense fruit may be a reflection of their smaller size and pericarp volume, due to the phytohormone imbalance in this line, as a consequence of the channelling of isoprenoids from gibberellins to carotenoids (Fray et al., 1995). Despite changes in protein levels of enzymes involved in fruit ripening (e.g. 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase, Table 2), Psy-1 plants developed at the same rate as the parental line and fruit ripened at the same rates.

PCA and PLS-DA analyses of the iTRAQ data do not show clustering of the individual lines in order to discriminate one from another (Supplementary Fig. S5 at JXB online). This indicates that the changes in protein profiles are due to small alterations in many proteins, rather than in one, abundant protein. The closest clustering is amongst Psy-1 sense plants, presumably because of the change in the level of the ASR1 protein (Table 2). A previous study on the Psy-1 lines (Fraser et al., 2007) detailed the metabolite changes in the fruit. It has not been possible to match these perturbations of the metabolome with those of the proteome found in the present study (Table 2), suggesting that there is no simple correlation between protein levels and associated metabolite concentrations, due to unknown regulatory effects.

Conclusions

This study has also shown that MudPIT is a robust and accurate method for detecting proteomic changes in GE crops. Therefore, it is a valid analytical tool for assessing substantial equivalence. Statistical analyses of the number and quantity of proteins within the four lines of tomato, grown under the same conditions, revealed no significant differences, but upon transformation and the introduction of the Psy-1 transgene, in either the sense or antisense orientation, unintended effects on the proteome did occur. The changes detected in the azygous line show that the transformation process itself does perturb the proteome, presumably because a fragment of the vector became integrated within the genome, thus perturbing the proteome, although the transgene was lost in the second generation of plants. Previous studies have shown significant alterations to the metabolome and transcriptome of both Psy-1 lines (Fraser et al., 2007), emphasizing the need for a holistic approach, using all the omic technologies, to judge substantial equivalence between parent and transgenic crops. Such comparisons should also be made in field conditions across growing seasons. If this approach is adopted by the regulators, then it may alleviate consumer concerns about GE crops. Taken in conjunction with the recent conclusion that GE plants are functionally equivalent to their non-GE counterparts and can be safely used in food and feed (European Food Safety Authority, 2011; Snell et al., 2012), the commercial growth and assessment of substantial equivalence of GE crops within Europe is now feasible.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Figure S1. Separation of iTRAQ-labelled peptides on a cation exchange (SCX) column.

Figure S2. Histogram of iTRAQ-labelled proteins and peptides, showing accuracy of quantitation.

Figure S3. Product ion mass spectrum of iTRAQ-labelled peptide SAINNLVNELVR from tomato sample.

Figure S4. Regression line of the mean ratio of 25 tomato proteins from three iTRAQ experiments. The theoretical ratios are 1:1, 1:2, and 1:20.

Figure S5. PCA and PLS-DA of iTRAQ ratios for each tomato cultivar.

Table S1. Design of iTRAQ experiments to assess the proteome differences between tomato plants of different cultivars and between cultivars.

Table S2. Protein levels in fruit, expressed as a ratio to the wild type, Ailsa Craig.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Food Standards Agency (London, UK) for financial support (grant G03019). Douglas Lamont and Kenneth Beattie of the University of Dundee, Gary Woffendin of ThermoFisher Scientific, and Rod Watson at Applied Biosystems are thanked for their assistance in some aspects of the proteomics.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ESI-MS

electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- iTRAQ

isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification

- LC

liquid chromatography

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MudPIT

multidimensional protein identification technology

- TEAB

triethylammonium bicarbonate

References

- Boehm AM, Pütz S, Altenhöfer D, Sickmann A, Falk M. 2007. Precise protein quantification based on peptide quantification using iTRAQ™ BMC Bioinformatics 8 214–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramley PM. 2002. Regulation of carotenoid formation during tomato fruit ripening and development Journal of Experimental Botany 53 2107–2113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramley PM, Teulieres C, Blain I, Bird C, Schuch W. 1992. Biochemical characterisation of transgenic tomato plants in which carotenoid synthesis has been inhibited through the expression of antisense RNA to pTOM5 The Plant Journal 2 343–349 [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority 2011. Guidance for risk assessment of food and feed f10 ptrom genetically modified plants EFSA Journal 9 1–37 [Google Scholar]

- Fraser PD, Roemer S, Shipton CA, Mills PB, Kiano JW, Misawa N, Drake RG, Schuch W, Bramley PM. 2002. Evaluation of transgenic tomato plants expressing an additional phytoene synthase in a fruit-specific manner . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 99 1092–1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser PD, Enfissi EMA, Halket JM, Truesdale MR, Yu D, Gerrish C, Bramley PM. 2007. Manipulation of phytoene levels in tomato fruit: effect on isoprenoids, plastids and intermediary metabolism The Plant Cell 19 3194–3211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fray RG, Wallace A, Fraser PD, Valero D, Hedden P, Bramley PM, Grierson D. 1995. Constitutive expression of a fruit phytoene synthase gene in transgenic tomatoes causes dwarfism by redirecting metabolites from the gibberellin pathway The Plant Journal 8 693–701 [Google Scholar]

- Kalifa Y Gilad A Konrad Z Zaccai M Scolnik PA Bar-Zvi D 2004. The water- and salt-stress-regulated Asr1 (abscisic acid stress ripening) gene encodes a zinc-dependent DNA-binding protein Biochemical Journal 381 373–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp NA, Huber W, Sadowski PG, Charles PD, Lilley KS. 2010. Addressing accuracy and precision issues in iTRAQ quantitation Molecular and Cellular Proteomics 9 1885–1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn E, Gijzen M. 2009. Phytochemical diversity: the sounds of silent metabolism Plant Science 176 161–169 [Google Scholar]

- Long ML, Millar DJ, Kimura Y, Donovan G, Rees J, Fraser PD, Bramley PM, Bolwell GP. 2006. Metabolite profiling of carotenoid and phenolic pathways in mutant and transgenic lines of tomato: identification of a high antioxidant fruit line Phytochemistry 67 1750–1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattoo AK, Shukla V, Fatima T, Handa AK, Yachha SK. 2010. Genetic engineering to enhance crop-based phytonutrients (nutraceuticals) to alleviate diet-related diseases. In: Giardi MT, Rea G, Berra B, eds. Bio-farms for nutraceuticals: functional food and safety control by biosensors Boston, MA: Landes Bioscience and Springer Science + Business Media; 122–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGloughlin MN. 2010. Modifying agricultural crops for improved nutrition New Biotechnology 27 494–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar DJ Long M Donovan G Fraser P Boudet A-M Danoun S Bramley PM Bolwell GP 2007. Introduction of sense constructs of cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (CYP73A24) in transgenic tomato plants shows opposite effects on flux into stem lignin and fruit flavonoids Phytochemistry 68 1497–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moose SP, Mumm RH. 2008. Molecular plant breeding as the foundation for 21st century crop improvement Plant Physiology 147 969–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD 2006. An introduction to the food/feed safety consensus documents of the Task Force. Series on the safety of novel foods and feeds, no. 14 Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; 7–9 [Google Scholar]

- Ow SW, Salim M, Noirel J, Evans C, Rehman I, Wright PC. 2009. iTRAQ underestimation in simple and complex mixtures: ‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ Journal of Proteome Research 8 5347–5355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potrykus I. 2001. Golden rice and beyond Plant Physiology 125,1157–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricroch AE, Berge JB, Kuntz M. 2011. Evaluation of genetically engineered crops using transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic profiling techniques Plant Physiology 155 1752–1761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross PL, Huang YN, Marchese JN, Williamson B, Parker K, Hattan S, Khainovski N, Pillai S, Dey S, Daniels S, Purkayastha S, Juhasz P, Martin S, Bartlet-Jones M, He F, Jacobson A, Pappin DJ. 2004. Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics 3 1154–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Römer S, Fraser P, Kiano, Shipton J, Misawa C, Schuch N, Bramley P. 2000. Elevation of the provitamin a content of transgenic tomato plants Nature Biotechnology 18 666–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommens CM. 2010. Barriers and paths to market for genetically engineered crops Plant Biotechnology Journal 8 101–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu JS, Chellan S. 2010. Genetic engineering of vegetable crops. In: Sinha NK, Hui YH, Evranuz EO, Siddiq M, Ahmed J.eds. Handbook of vegetables and vegetable processing Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 83–105 [Google Scholar]

- Snell C, Bernheim A, Berge J-B, Kuntz M, Pascal G, Paris A, Ricroch AE. 2012. Assessment of the health impact of GM plant diets in long-term and multigenerational animal feeding trials: a literature review Food and Chemical Technology 50 1134–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting L, Rad R, Gygi SP, Haas W. 2011. MS3 eliminates ratio distortion in isobaric labeling-based multiplexed quantitative proteomics Nature Methods 8 937–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojanowicz M, Latoszek A, Pobozy E. 2010. Analysis of genetically modified food using high performance separation methods Analytical Letters 43 1653–1679 [Google Scholar]