Abstract

Background

Posttraumatic stress disorder is a major public health concern with long term sequelae. There are no accepted interventions delivered in the immediate aftermath of trauma. This study tested an early intervention aimed at modifying the memory to prevent the development of PTSD prior to memory consolidation.

Methods

Patients (N=137) were randomly assigned to receive 3 sessions of an early intervention beginning in the emergency department (ED) compared to an assessment only control group. Posttraumatic stress reactions (PTSR) were assessed at 4 and 12 weeks post-injury and depression at baseline and week 4. The intervention consisted of modified prolonged exposure including imaginal exposure to the trauma memory, processing of traumatic material, and in vivo and imaginal exposure homework.

Results

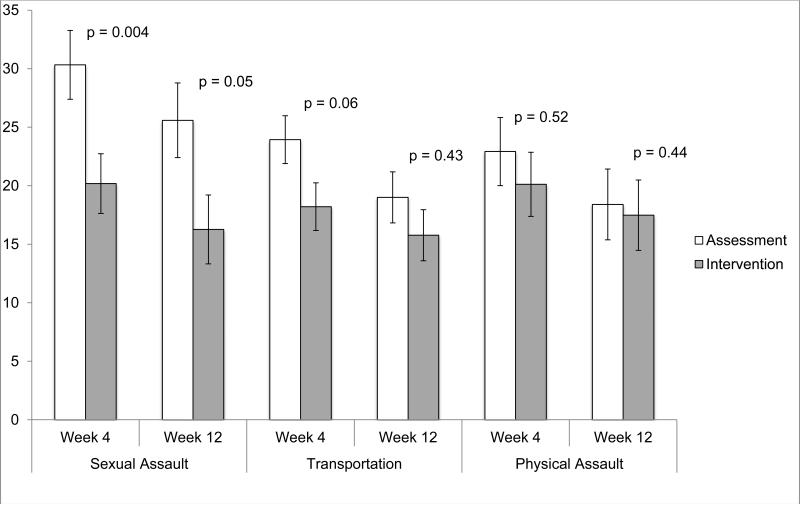

Patients were assessed an average of 11.79 hours post-trauma. Intervention participants reported significantly lower PTSR than the assessment group at 4 weeks post-injury, p < 0.01, and at 12 weeks post-injury, p < 0.05, and significantly lower depressive symptoms at Week 4 than the assessment group, p < 0.05. In a subgroup analysis the intervention was the most effective at reducing PTSD in rape victims at Week 4 (p=.004) and Week 12 (p=.05).

Conclusions

These findings suggest that the modified prolonged exposure intervention initiated within hours of the trauma in the ED is successful at reducing PTSR and depression symptoms one and three months after trauma exposure and is safe and feasible. This is the first behavioral intervention delivered immediately post-trauma that has been shown to be effective at reducing PTSR.

Keywords: early intervention, secondary prevention, PTSD, Acute Stress Disorder, prolonged exposure, memory consolidation

Approximately 60.7% of men and 51.2% of women are estimated to experience a traumatic event in their lifetimes.(1) While a majority of individuals will experience symptoms of posttraumatic stress in the immediate aftermath of a trauma, prospective studies indicate that these reactions typically extinguish over time.(2) However, a subset of individuals will develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The majority of prevention research has focused on psychological debriefing (PD). PD typically includes seven phases that incorporate opportunities for survivors to talk about their trauma reactions and receive support and psychoeducation.(3) Unfortunately, controlled research on PD has suggested that it is either ineffective or even potentially harmful, which has led experts to discourage its use as a prevention approach for PTSD.(4) With no clear candidate currently available for early intervention, research identifying short-term, cost-effective, and easily disseminable interventions is extremely important, especially given the significant public health impact of PTSD.

Pharmacological prevention studies have tested early administration of propranolol, a β–adrenergic blocker, with contradictory results.(5, 6, 7, 8) A well-controlled study by Hoge and colleagues(8) found no benefit of propranolol over placebo. Early administration of hydrocortisone has shown promise in reducing chronic stress and PTSD symptoms in cardiac surgery patients(9) and emergency room patients,(10) but more research is needed. Nonrandomized studies of morphine and ketamine administration show some association with reduced PTSD rates, but controlled studies are needed.(11, 12, 13)

Pilot studies of brief psychosocial interventions have been conducted as well. A memory-restructuring intervention developed by Gidron and colleagues(14) demonstrated some preliminary support in a pilot study, but follow-up research found no intervention effect.(15) Psychoeducation delivered via self-help booklets has not proven useful as a prevention strategy.(16, 17) A video-based intervention providing psychoeducation to rape victims immediately prior to a forensic rape exam has shown preliminary support,(18, 19) but would not apply to other trauma types. The most successful psychosocial interventions thus far have been brief cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) implemented with individuals who meet criteria for Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) and typically include 4-6 sessions of techniques such as psychoeducation, exposure therapy, cognitive therapy, and stress management.(20) CBT approaches are typically initiated within 2-4 weeks of the initial trauma and have been shown to be superior to supportive counseling.(21, 22) However, a study with female assault survivors(23) found that although early CBT accelerated recovery rates compared to supportive counseling, rates of PTSD severity were equivalent at a 9-month follow-up. A recent randomized trial tested cognitive therapy, prolonged exposure, and a wait-list control group versus a SSRI and pill placebo condition approximately one month post-trauma, and found that only the two psychological interventions were effective at reducing PTSD rates compared to placebo or waitlist.(24) While CBT seems promising, it has only been tested with individuals already diagnosed with ASD 2-4 weeks post-trauma. Therefore, there are currently no good candidates for immediate intervention following trauma exposure.

In basic and experimental research, exposure to the conditioned stimulus (CS) in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) is referred to as extinction training. As a therapeutic technique in humans, we refer to it as exposure therapy. Research has established that exposure therapy, which relies on fear extinction through engagement with traumatic memories and cues, is an efficacious treatment for PTSD.(25) PTSD may be viewed as a failure of recovery caused in part by a failure of fear extinction following trauma.(26) This is supported by animal research demonstrating early extinction training has the potential to modify consolidation of the original fear memory.(27) In this study, rats were fear conditioned and then given extinction training either 10 minutes, 1 hour, 24 hours, or 72 hours after acquisition, and their fear was evaluated. Animals extinguished at 72 hours exhibited robust indices of fear, whereas animals extinguished at 10 minutes exhibited none of the indices of fear. The lack of fear indices in the short interval group would seem to be explained most parsimoniously in terms of prevention of consolidation of the fear memory. Perhaps consistent with this, evidence is emerging for a neurobiological difference between short and long interval extinction. Cain and colleagues(28) reported that immediate extinction is not affected by the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel (L-VGCC) inhibitor nifedipine, and another study(29) found that fear extinction initiated 1 hour after fear acquisition reversed a fear conditioning-induced change in a particular glutamate receptor (the GluR1 subunit of the AMPA receptor) within the amygdala. This reversal did not occur when extinction was initiated 24 hours after acquisition.

A translational study with humans indicated that participants who received extinction training 10 minutes after fear conditioning had significantly lower fear potentiated startle than participants receiving extinction training after 72 hours.(30) Despite these promising findings, no studies to date have examined the potential of early extinction training in preventing the development of PTSD in recent trauma survivors.

For chronic PTSD, practice guidelines point to CBT as efficacious, with prolonged exposure (PE) having particularly strong evidence as a first-line treatment for PTSD.(31, 32) PE, which requires repeatedly confronting memories and reminders of the traumatic event, shares similarities with extinction training, but is quite distinct from PD. Rose and colleagues(4) speculate that adverse effects found in PD may be due to intense imaginal exposure in single debriefing sessions, without opportunity for habituation and emotional processing, which are emphasized as important mechanisms underlying the effectiveness of exposure therapy. Preliminary evidence supports the use of exposure for individuals with ASD.(21, 22, 23, 33) An initial pilot feasibility study of an exposure-based treatment for patients presenting to an emergency department (ED) within hours of a traumatic event indicated that those who received the intervention had lower levels of depression and clinician-rated distress one week later.(34) However, no randomized controlled studies of exposure therapy in the immediate aftermath of trauma have been conducted to date.

This translational randomized controlled study examined whether the use of modified prolonged exposure (PE) therapy in an ED setting in patients experiencing a DSM criterion A trauma would significantly reduce the severity of posttraumatic stress reactions at 4 and 12 weeks post-trauma. Due to estimated depression comorbidity rates of 44.5% in PTSD patients one month post-trauma,(35) depression rates were also assessed. We predicted that patients receiving the intervention would have reduced severity of posttraumatic stress at 4 and 12 weeks post-trauma and reduced severity of depression at 4 weeks post-trauma compared to patients who were repeatedly assessed without intervention.

Methods

Study Design

Participants aged 18-65 who presented to the ED within 72 hours of experiencing a trauma and met criterion A of the DSM-IV(36) were screened for eligibility. Patients who spoke English, had a memory of the event, and were alert and oriented were included in the study. Information on exclusion criteria was obtained via patient self report or documentation in medical charts. The most common reasons for exclusion were not meeting criterion A for PTSD (n = 1737), loss of consciousness longer than 5 minutes (n = 1076), current intoxication (n = 655), and failure to meet age criteria (n = 978). Among patients who declined (n = 1221), the most common reasons cited included lack of interest in receiving intervention (n = 425), being in too much pain (n = 205), and wanting to leave the hospital as soon as possible (n = 224). More information on screening and enrollment is reported in Malcoun et al.(37) Acutely injured Criterion A trauma patients receiving care in the ED were randomized to receive modified PE or assessment only.

Setting

This study was conducted at a public hospital ED with the largest Level One trauma center in Georgia. The hospital research oversight committee and university IRB approved this investigation. The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00895518.

Procedure

Screening and Enrollment

Patients were screened for eligibility by one of three assessors with a minimum of a master's degree in psychology or social work. Staff were positioned in the trauma area of the ED from 7 am- 7 pm daily. Assessors identified potential patients via the tracking board and interviewed interested patients for eligibility. Participants provided written informed consent, completed the initial assessment, and were compensated $20 for their time.

Initial Assessment

Assessors collected demographic information, baseline depression and peritraumatic distress symptoms, and trauma history at the initial assessment. Envelopes containing computer-generated patient random assignments (either to immediate intervention or assessment only) were given to the patient and their nurse after the initial evaluation to ensure that assessors remained blind. The on-call therapist immediately provided the intervention to those assigned to this condition.

Intervention

Therapists were trained in PE(38, 39) and this modified protocol and had a master's or doctoral degree in psychology or social work. Patients received three, hour-long sessions of a modified PE intervention, distributed one week apart. See Table 1 for a detailed description of the intervention. Approximately 85% of participants were compliant with all homework assignments, or were missing only one component, at both follow-up sessions.

Table 1.

Modified prolonged exposure session outline.

| Session | Task |

|---|---|

| 1 -1 hour | Introduce the intervention (2 min) |

| Imaginal exposure (30-45 min) | |

| Process the imaginal exposure (10-15 min) | |

| Identify behavioral exposure(s) for the coming week (5 min) | |

| Explain normal reactions to trauma and identify self-care tasks for the coming week (3 min) | |

| Breathing retraining (5 min) | |

| Schedule next session and remind patient to maintain the blind (1 min) | |

| 2 -1 hour | Review homework (5 min) |

| Imaginal exposure (30-45 min) | |

| Process the imaginal exposure (10-15 min) | |

| Identify behavioral exposure(s) for the coming week (3 min) | |

| Identify self-care tasks for the coming week (3 min) | |

| Schedule next session and remind patient to maintain the blind (1 min) | |

| 3 -1 hour | Review homework (5 min) |

| Imaginal exposure (30-45 min) | |

| Process the imaginal exposure (10-15 min) | |

| Identify behavioral exposure(s) to continue working on after treatment ends (3 min) | |

| Identify self-care tasks to continue prioritizing in the coming weeks/months (3 min) | |

| Remind the patient to attend 4 and 12 week assessment and to maintain the blind (1 min) |

Note. Component lengths varied based on the individual needs of each patient. Total session length is recommended to not exceed one hour.

Follow-up assessments

Blinded assessors administered the Update Trauma Interview (UTI)(40), the PTSD Symptom Scale-I (PSS-I)(41), the PDS(42), and the Additional Treatment Inventory (ATI)(40) 4 and 12 weeks following enrollment in the ED. Patients were given the BDI-II(43) at the 4 week follow-up to assess depressive symptoms. Approximately 88% of 4 week follow-ups and 84% of 12 week follow-ups were conducted in person. In cases where a participant was unable to return for follow-up in person, the option to conduct the interview by phone (n=7 at 4 week, n=10 at 12 week) or by mail (n=5 at 4 week, n=5 at 12 week) was offered to minimize missing data. Patients meeting DSM criteria for PTSD at the 3-month follow-up were offered the full 9-session PE treatment(38, 39) at no charge.

Measures

Outcome measures were gathered via clinical interview and self-report. Information entered into the database was cross-checked by a second rater to ensure consistency of coding and accuracy. All assessments were audio recorded for reliability.

Trauma Interviews

The Standardized Trauma Interview (STI)(40) is a 41-item clinician-administered interview gathering information on relevant aspects of the trauma and demographic information at baseline. For the current study, inter-rater agreement across three independent raters was 0.99. The Update Trauma Interview (UTI)(40) is a 30-item version of the STI used to gather post-trauma information. Inter-rater agreement across three independent raters was 0.99. The Additional Treatment Inventory (ATI)(40) consists of 3 questions assessing additional treatment sought after the completion of study treatment.

PTSD Diagnostic Scale (PDS)(42)

This 49-item self-report yields a DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis and PTSD severity and screens for prior traumatic events. The PDS has high internal consistency. Test-retest reliability was good, from .74 to .85. High diagnostic agreement (82%) with the SCID was noted.(42)

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)(44)

This 28-item retrospective self-report assesses 5 categories of negative childhood experiencesemotional neglect, emotional abuse, physical neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse and has excellent psychometric properties.(45, 46, 47)

Immediate Stress Reaction Checklist (ISRC)(48)

This 26-item self-report examines acute stress responses regarding the current presenting trauma (dissociation, reexperiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal). Items are rated from 0 (not true) to 2 (very or often true). The ISRC demonstrates strong internal consistency (.86).(48)

Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition(43)

This 21-item self-report assesses depression symptoms in the past two weeks with excellent psychometric properties.(43, 49)

PTSD Symptom Scale, Interview Version (PSS-I)(41)

The PSS-I is a clinician-administered inventory corresponding to the 17 DSM-IV PTSD symptoms, each rated on a 0-3 scale with excellent psychometric properties.(50) Inter-rater agreement across three independent raters was 0.99 in the current study. The PSS-I has been utilized as both a continuous measure of symptom severity, as well as to assess for diagnostic status that shows moderate to high agreement with the SCID and CAPS interview.(50)

Data Analytic Plan

The data were initially screened for differences across the conditions (intervention/assessment) in baseline measures of childhood trauma, initial stress reaction, depression, and PTSD from past traumas. Variables found to significantly differ amongst the groups at p < 0.15 were included as covariates in all subsequent analyses.

Baseline symptom levels for PTSD could not be validly obtained due to assessment within hours of trauma exposure. Baseline PTSD symptoms from past trauma exposure (assessed on the PDS) were included as covariates. Missing values for week 4 and week 12 data were handled with multiple imputation. The NORM(51) software package was used to generate 100 complete datasets in which demographic variables, pretreatment self-report measures, treatment condition, and trauma type were used as auxiliary variables. Estimates were pooled using the guidelines of Rubin.(52) Linear mixed effect models were used to obtain predicted mean values for outcomes at each assessment point (weeks 4 and 12). Within each model, time and treatment condition were included as fixed effects as well as a time x treatment interaction. Covariates in the model included trauma type and variables that were found to differ amongst the intervention and assessment groups at baseline. In all models, a random effect was included for intercept and time. All comparisons were planned and a Benjamini and Hochberg(53) approach was used to address issues of multiple comparisons. This approach provides better control of Type I error rates when conducting multiple hypothesis tests as compared to more conservative approaches.(54)

Results

Subjects

Average time since trauma (in hours) was M = 11.79 (Median = 6.92; SD = 12.90) for the entire sample, with no significant differences between assessment and intervention groups, t (128) = 0.66, p = 0.51. The majority of the sample (88%) was enrolled within 24 hours post-trauma. Of the 137 participants who were enrolled in the study, 102 (74%) completed 4 week follow-up and 91 (66%) completed 12 week follow-up. No significant group differences in drop-out rates were detected, X2 = 1.92, p = 0.17. No patients reported a desire to withdraw from the study as a result of their participation, and no study-related adverse effects were reported. Demographic information is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample demographic information.

| Intervention (n = 69) | Assessment (n = 68) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male – n (%) | 25 (36.20%) | 23 (33.80%) |

| Female – n (%) | 44 (63.80%) | 45 (66.20%) |

| Age – M (SD) | 30.17 (12.08) | 32.78 (11.12) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White – n (%) | 5 (7.20%) | 13 (19.10%) |

| Black – n (%) | 56 (81.2%) | 52 (76.50%) |

| Native American – n (%) | 2 (2.90%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other – n (%) | 6 (8.70%) | 3 (4.40%) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single – n (%) | 48 (69.56%) | 38 (55.88%) |

| Married or Cohabitating – n (%) | 13 (18.84%) | 24 (35.30%) |

| Divorced or Separated – n (%) | 4 (5.80%) | 2 (2.94%) |

| Other – n (%) | 4 (5.80%) | 4 (5.88%) |

| Minutes Since Presenting Trauma | 751.95 (803.04) | 663.55 (747.73) |

| Trauma Type | ||

| Rape – n (%) | 28 (40.58%) | 19 (27.90%) |

| Non Sexual Assault – n (%) | 19 (27.54%) | 18 (26.50%) |

| Motor Vehicle Accident – n (%) | 20 (28.98%) | 26 (38.20%) |

| Other – n (%) | 2 (2.90%) | 5 (7.4%) |

| Prior Trauma Exposure | ||

| Rape – n (%) | 10 (14.5%) | 7 (10.3%) |

| Non-Sexual Assault – n (%) | 9 (13.0%) | 9 (13.2%) |

| Motor Vehicle Accident – n (%) | 7 (10.1%) | 15 (22.1%) |

| Other – n (%) | 4 (5.8%) | 2 (2.9%) |

| No Prior Trauma – n (%) | 39 (56.5%) | 35 (51.5%) |

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A logistic regression demonstrated no significant differences in baseline demographics between conditions. Univariate ANOVA's suggested that assessment and intervention conditions differed on ISRC numbing (F (1, 135) = 4.39, p < 0.05) and ISRC re-experiencing (F (1, 135) = 6.70, p < 0.01). ISRC Peritraumatic depersonalization (F (1, 135) = 3.09, p = 0.08), and the ISRC post event dissociation approached significance (F (1, 135) = 3.33, p = 0.07). Notably, the ISRC responses were higher in the intervention condition compared to the assessment condition, suggesting that the intervention group may have had more severe trauma reactions during the peri-trauma period. These variables were included as covariates in all subsequent models. To ensure treatment adherence and competence, 20% of therapy sessions were rated for treatment integrity. Using a scale from 1 (“very poor”) to 7 (“excellent”), mean therapist skill and adherence was rated as 6.19 (SD = 0.83) or “very good”.

Efficacy Analysis

A mixed effect model was used to assess differences in PSS-I scores at the 4-and 12-week follow-up assessments controlling for covariates (Table 3). A significant main effect was found for time (p = 0.04) and for treatment condition (p = 0.02). Intervention group participants reported significantly lower PSS scores at the 4-week follow-up (M = 19.09, 95% CI, 15.51 to 22.68) than the assessment group (M = 24.54, 95% CI, 21.22 to 27.87). Similar results were obtained for the 12-week follow-up with the intervention group (M = 15.47, 95% CI, 11.60 to 19.34) having significantly lower scores than the assessment group (M = 20.33, 95% CI, 16.79 to 23.87). The time x treatment condition was not significant (p = 0.29). Effect size estimates for differences at week 4 and week 12 for the PSS suggested treatment had a medium effect (4-week - D = 0.38, 12-week - D = 0.34). A similar approach was used to evaluate differences in BDI and PDS scores from baseline to week 4. For the BDI, a significant main effect was found for time (p = 0.02) and for treatment condition (p < 0.01). The intervention group (M = 15.64, 95% CI, 11.71 to 18.37) reported significantly lower BDI scores than the assessment group at week 4 (M = 21.37, 95% CI, 18.38 to 24.14). Effect size estimates for week 4 differences on the BDI indicated a medium effect for treatment (D = 0.35). For the PDS, assessing PTSD symptoms from a prior trauma, there was not a significant main effect for treatment (p = 0.11), or time (p = 0.98), or a time x treatment interaction (p = 0.16). Effect size estimates suggested that treatment had a small effect on PDS scores at week 4 (D = 0.11). Taken together, the findings of the current study support the hypothesis that the intervention reduced posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms.

Table 3.

Comparison of PTSD for Current Trauma, Depression, and PTSD for Prior Trauma Across Intervention and Assessment Conditions.

| Intervention (n=69) | Assessment (n = 68) | Effect size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcomes | ||||

| PSS | ||||

| Week 4* | a,y19.09±1.83 (15.51-22.68) | b,y 24.54±1.70 (21.22-27.87) | 0.38 | |

| Week 12* | a,z15.47±1.98 (11.60-19.34) | b,z 20.33±1.80 (16.79-23.87) | 0.34 | |

| BDI | ||||

| Baseline | a,y18.60 ±1.51 (15.64-21.55) | a,y 21.26±1.47 (18.38-24.14) | ||

| Week 4* | b,z 15.04±1.70 (11.72-18.37) | a,y 21.37±1.63 (18.38-24.14) | 0.35 | |

| PDS | ||||

| Baseline | a,y18.90±1.80 (15.35-22.39) | a,y 19.46±1.78 (15.97-22.95) | ||

| Week 4 | a,y 18.90±2.34 (14.30-23.50) | a,y 23.76±2.29 (19.27-28.24) | 0.11 | |

| Baseline Covariates | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ISRC-Numbing | 3.10 (0.23) | 2.50 (0.22) | 0.06 |

| ISRC- Depersonalization | 1.97 (0.21) | 1.55 (0.16) | 0.1 |

| IRSC-Dissociation | 2.33 (0.22) | 1.89 (0.20) | 0.11 |

| ISRC-Reexperiencing | 4.84 (0.17) | 4.20 (0.21) | 0.02 |

| CTQ | 48.52 (2.91) | 48.87 (2.60) | 0.91 |

Note:

denotes significant main effect for group at p < 0.05 based on findings from mixed effect models.

denotes significant main effect for group at p < 0.05 based on findings from mixed effect models.

denotes significant main effect for time at p < 0.05 based on findings from mixed effect models ± Values are standard errors.

denotes significant main effect for time at p < 0.05 based on findings from mixed effect models ± Values are standard errors.

Values in parenthesis are 95% CI. Means and standard errors are pooled estimates obtained from 100 datasets generated from multiple imputation. N=137 participants. ISRC = Initial Stress Reaction Checklist. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory. CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. PDS = PTSD Diagnostic Scale. PSS-I = PTSD Symptom Scale – Interview † = Estimated mean based on linear mixed effect

PTSD Diagnosis

A PTSD diagnosis was indicated by a response of 2 or greater on the PSS-I on at least 1 of the 4 re-experiencing items, 3 of the 6 avoidance items, and 2 of the 5 hyperarousal items. Using these criteria, 54% of the intervention condition and 49% of the assessment condition did not meet criteria for PTSD at week 4. This difference was not significant, χ2 = 0.28, p = 0.60. At week 12, 74% of the intervention condition and 53% of the assessment condition did not meet criteria for PTSD. This difference was statistically significant, χ2 = 4.16, p = 0.04. Using these values, the number needed to treat (NNT) with this approach at week 4 and 12 were 20 and 5 respectively. Clinically significant depression was defined as a score of 13 or greater on the BDI.55 Using these criteria, 51% of the intervention condition and 32% of the assessment condition did not meet criteria for depression. This difference approached significance, χ2 = 3.04, p = 0.08. The NNT to treat for depression at week 4 was 6. Comorbid depression and PTSD diagnoses were identified for 41.76% of the sample.

Follow-up analyses were conducted to determine the impact of treatment across different types of trauma (Figure 1). To accommodate the reduced power for these analyses, independent comparisons were made for the 4-week and 12-week trauma symptoms using the previously described alpha correction. For rape victims (n=47), those in the intervention condition (M = 20.10, SE = 2.38) reported significantly lower (p < 0.01, Cohen's D = 0.70) PSS scores than those in the assessment condition (M = 30.45, SE = 2.73) at week 4. Similar findings were obtained at week 12, with intervention participants (M = 16.63, SE = 3.05) reporting significantly lower (p = 0.05, Cohen's D = 0.52) scores than the assessment condition (M = 25.04, SE = 3.37). For victims of transportation accidents (n=46), the difference between the intervention condition (M = 17.95, SE = 2.66) and assessment condition (M = 24.14, SE = 1.95) approached significance (p = 0.06, Cohen's D = 0.49) at week 4. However, there were no significant differences amongst the groups at week 12 (p = 0.43, Cohen's D = 0.33). For physical assault victims (n=37), there were no significant differences at week 4 (p = 0.52, Cohen's D = 0.14) or at week 12 (p = 0.44, Cohen's D = 0.10). The sample size for the “other” trauma group (n=7) was not sufficient to allow for comparisons.

Figure 1.

Group differences in PTSD severity at week 4 and week 12 as a function of trauma type. Error bars correspond to ± 1 SE.

Discussion

Trauma survivors at an ED in a level I trauma center were randomly assigned to a modified prolonged exposure intervention or assessment only within 11-12 hours on average of experiencing a severe traumatic event. Those receiving the modified PE intervention reported significantly less PTSD and depression severity in the months following the trauma than those assigned to assessment only. These findings suggest that this early intervention is effective at reducing symptoms of posttraumatic stress at one and three months post-trauma and depression at one month post-trauma, is safe, and is feasible. Higher effect sizes for the intervention were found among rape victims, which is noteworthy given that rape has been identified as the trauma most likely to lead to the development of PTSD.(1) The intervention targeted the trauma that brought patients into the ED and did not appear to effect PTSD symptoms associated with prior traumatic events.

These results have important implications for research on the immediate response to trauma. First, this is the first behavioral intervention delivered in the hours following trauma exposure that has been shown to be effective at reducing posttraumatic stress reactions. Because some studies indicated the possibility that early interventions such as debriefing could interfere with natural recovery following trauma exposure,(56, 57) the field has shied away from early intervention studies. However, debriefing is very different from the therapeutic exposure used herein and it is our hope that these promising results will now re-open this important therapeutic question. Our modified PE is quite distinct from debriefing in that it is based on individual versus group delivery, includes other components (breathing relaxation, in vivo exposure, attention to cognitions, self-care), and importantly, involves multiple repetition of the trauma narrative to allow for fear extinction within and between sessions for homework.

Secondly, the intervention and the timing of the intervention is based both on translational and clinical research. Exposure therapy has received more empirical support than any other intervention for ASD and PTSD, but has never been attempted within hours of the traumatic event. Basic and preclinical research has indicated that the timing of extinction training following fear conditioning is critical. Myers and colleagues(27) identified signs of fear in animals given extinction training after 72 hours, but not in those given extinction training after 10 minutes. This very early extinction training may be protective against the physiological and psychological effects of traumatic fear memories.(27) Similar to extinction training, exposure therapy is theorized to reduce PTSD symptoms by promoting fear activation and habituation of conditioned fear reactions through engagement with traumatic memories, while allowing integration of corrective information regarding the trauma.(58) Although several mechanisms may be involved, we suggest that the modified PE intervention presented here may be able to prevent the development of PTSD through similar mechanisms by encouraging engagement with the trauma memory and providing an opportunity for fear habituation and processing of unhelpful cognitions, thus modifying the memory before it is consolidated.

Some limitations should be noted. Since we felt that it would not be valid to measure PTSD symptoms within hours of trauma exposure, no baseline measure of PTSD was collected. Thus, we are unable to calculate symptom improvement from baseline to follow-up, and must depend on between group comparisons at follow-up assessments. The current findings also identified higher immediate stress reactions among intervention participants, which may have allowed more room for improvement, although these initial differences were controlled for statistically.

Because of the pilot nature of this study and desire to minimize participant burden, this study was not able to assess the impact of the intervention on other outcome measures, such as functioning. In addition, dropout rates were substantial, although complete data was obtained at the 4-week follow-up for the majority of our sample (74%). Such rates are similar to those of other recent large scale trials that recruited patients shortly after trauma exposure.(24, 59)

Similarly, the current study's sample size was not sufficiently powered to detect the smaller effects that were observed on some of the outcome measures such as the PDS. It is unclear if a Type II error was committed in retaining the null hypothesis for these analyses. Replication of these findings in larger samples is needed to confirm the reliability of these findings. Additionally, future studies examining reduction of posttraumatic stress reactions in the acute aftermath of trauma exposure should be powered for small effects.

This study may have benefited from a longer follow-up period. However, the decision to conduct a 12-week follow-up was made based on research suggesting that by 3-4 months post-trauma, PTSD symptoms have typically become chronic and are unlikely to recover spontaneously.(2, 60, 56) The lack of 24 hour ED coverage is another limitation, although most patients arriving overnight could be screened in the morning prior to discharge.

In addition, because the current study was aiming to answer the question of whether PTSD can be prevented by intervening prior to memory consolidation, our intervention was specific to the presenting trauma only and limited by 3 brief sessions. Memories from past traumatic events were not addressed, and thus, not surprisingly, the intervention effects did not generalize to PTSD symptoms associated with prior traumas.

Lastly, the public health reach of this intervention may be limited, providing the most benefit to patients most at risk.(61) Expanding the reach of early intervention should be a focus of further research.

Clearly more research is needed, particularly to determine who requires early intervention and who will recover naturally without using valuable resources unnecessarily, what is the optimal window for intervention, how many sessions, and what type of treatment for which patient. It will be important to test this early intervention in the field, with both civilians and military personnel, and with delivery by non- or para-professionals to increase dissemination. Larger studies that can examine and confirm specific mechanisms of change are also greatly needed. A long-standing hope of mental health research is to prevent the development of psychopathology in those at risk (secondary prevention) instead of being limited to symptom treatment after disease onset (tertiary prevention). Although further research is needed, this prevention model could have significant public health implications. Work is needed to determine the best policy and practice guidelines for implementation of this type of early intervention. Translational research providing new approaches to intervention prior to memory consolidation may provide such an approach with PTSD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant No. R34 MH083078, “Effects of Early Psychological Intervention to Prevent PTSD”, and the Emory Center for Injury Control, Center for Disease Control Grant No. 5R49CE001494. Dr. Rothbaum had full access to all of the data in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Clinicaltrials.gov: Examining the Effectiveness of an Early Psychological Intervention to Prevent Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00895518?term=rothbaum&rank=1; NCT00895518

Disclosures The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothbaum BO, Foa EB, Riggs D, Murdock T, Walsh W. A prospective examination of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. J Trauma Stress. 1992;5:455–475. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNally RJ, Bryant RA, Ehlers A. Does early psychological intervention promote recovery from posttraumatic stress? Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2003;4(2):45–79. doi: 10.1111/1529-1006.01421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose SC, Bisson J, Churchill R, Wessely S. Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;2:CD000560. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitman RK, Sanders KM, Zusman RM, Healy AR, Cheema F, Lasko NB, et al. Pilot study of secondary prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder with propranolol. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(2):189–92. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein MB, Kerridge C, Dimsdale JE, Hoyt DB. Pharmacotherapy to prevent PTSD: Results from a randomized controlled proof-of-concept trial in physically injured patients. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):923–32. doi: 10.1002/jts.20270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaiva G, Ducrocq F, Jezequel K, Averland B, Lestavel P, Brunet A, et al. Immediate treatment with propranolol decreases posttraumatic stress disorder two months after trauma. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(9):947–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoge EA, Worthington JJ, Nagurney JT, Chang Y, Kay EB, Feterowski CM, et al. Effect of acute posttrauma propranolol on PTSD outcome and physiological responses during script-driven imagery. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18(1):21–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schelling G, Kilger E, Roozendaal B, de Quervain DJ, Briegel J, Dagge A, et al. Stress doses of hydrocortisone, traumatic memories, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in patients after cardiac surgery: a randomized study. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(6):627–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zohar J, Yahalom H, Kozlovsky N, Cwikel-Hamzany S, Matar MA, Kaplan Z, et al. High dose hydrocortisone immediately after trauma may alter the trajectory of PTSD: interplay between clinical and animal studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(11):796–809. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant RA, Creamer M, O'Donnell M, Silove D, McFarlane AC. A study of the protective function of acute morphine administration on subsequent posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(5):438–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holbrook TL, Galarneau MR, Dye JL, Quinn K, Dougherty AL. Morphine use after combat injury in Iraq and post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(2):110–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGhee LL, Maani CV, Garza TH, Gaylord KM, Black IH. The correlation between ketamine and posttraumatic stress disorder in burned service members. J Trauma. 2008;64(2 Suppl):S195–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318160ba1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gidron Y, Gal R, Freedman S, Twiser I, Lauden A, Snir Y, et al. Translating research findings to PTSD prevention: results of a randomized-controlled pilot study. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14(4):773–80. doi: 10.1023/A:1013046322993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gidron Y, Gal R, Givati G, Lauden A, Snir Y, Benjamin J. Interactive effects of memory structuring and gender in preventing posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(2):179–82. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000254676.11987.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turpin G, Downs M, Mason S. Effectiveness of providing self-help information following acute traumatic injury: randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:76–82. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scholes C, Turpin G, Mason S. A randomized controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of providing self-help information to people with symptoms of acute stress disorder following a traumatic injury. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(11):2527–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnick H, Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG, Holmes M. Description of an early intervention to prevent substance abuse and psychopathology in recent rape victims. Behav Modif. 2005;29:156–88. doi: 10.1177/0145445504270883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resnick H, Acierno R, Waldrop AE, King L, King D, Danielson C, et al. Randomized controlled evaluation of an early intervention to prevent post-rape psychopathology. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(10):2432–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Litz BT, Bryant RA. Early cognitive-behavioral interventions for adults. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, editors. Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Guilford Press; New York: 2009. pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryant RA, Harvey AG, Dang ST, Sackville T, Basten C. Treatment of acute stress disorder: a comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(5):862–6. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryant RA, Sackville T, Dang S, Moulds M, Guthrie R. Treating acute stress disorder: An evaluation of cognitive behavior therapy and supportive counseling techniques. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(11):1780–1786. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foa EB, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. An evaluation of three brief programs for facilitating recovery after assault. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19:29–43. doi: 10.1002/jts.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shalev AY, Ankri Y, Israeli-Shalev Y, Peleg T, Adessky R, Freedman S. Prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder by early treatment: Results from the Jerusalem Trauma Outreach and Prevention Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(2):166–176. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cahill S, Rothbaum B, Resick P, Follette V. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, editors. Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2009. pp. 139–222. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothbaum BO, Davis M. Applying learning principles to the treatment of post-trauma reactions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1008:112–121. doi: 10.1196/annals.1301.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers KM, Ressler KJ, Davis M. Different mechanisms of fear extinction dependent on length of time since fear acquisition. Learn Mem. 2006;13(2):216–223. doi: 10.1101/lm.119806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cain CK, Godsil BP, Jami S, Barad M. The L-type calcium channel blocker nifedipine impairs extinction, but not reduced contingency effects, in mice. Learn Mem. 2005;12(3):277–84. doi: 10.1101/lm.88805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao SC, Hsiao YH, Gean PW. Extinction training in conjunction with a partial agonist of the glycine site on the NMDA receptor erases memory trace. J Neurosci. 2006;26(35):8892–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0365-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norrholm SD, Vervliet B, Jovanovic T, Boshoven W, Myers KM, Davis M, et al. Timing of extinction relative to acquisition: A parametric analysis of fear extinction in humans. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122(5):1016–1030. doi: 10.1037/a0012604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, editors. Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Institute of Medicine . Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: An assessment of the evidence. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryant RA, Mastrodomenico J, Felmingham KL, Hopwood S, Kenny L, Kandris E, et al. Treatment of acute stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(6):659–667. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothbaum BO, Houry D, Heekin M, Leiner AS, Daugherty J, Smith LS, et al. A pilot study of an exposure-based intervention in the ED designed to prevent posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:326–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shalev AY, Freeman S, Peri T, Brandes D, Sahar T, Orr SP, et al. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(5):630–637. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malcoun E, Houry D, Arndt-Jordan C, Kearns MC, Zimmerman L, Hammond-Susten M, et al. Feasibility of identifying eligible trauma patients for posttraumatic stress disorder intervention. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11(3):274–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foa EB, Hembree E, Rothbaum BO. Prolonged Exposure Therapy for PTSD: Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences, Therapist Guide. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothbaum BO, Foa EB, Hembree E. Reclaiming Your Life from a Traumatic Experience: Client Workbook. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foa EB, Rothbaum BO. Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD. The Guilford Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 1993;6:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9(4):445–451. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory. 2nd ed. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernstein D, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio TX: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fink L, Bernstein DP, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M. Initial reliability and validity of the Childhood Trauma Interview: A new multidimensional measure of childhood interpersonal trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1329–1335. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fein J, Kassam-Adams N, Vu T, Datner E. Emergency department evaluation of acute stress disorder symptoms in violently injured youth. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;28:391–39. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.118225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beck AT. Beck InterpreTrak. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foa EB, Tolin DF. Comparison of the PTSD Symptom Scale–Interview Version and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13(2):181–191. doi: 10.1023/A:1007781909213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. Chapman & Hall; London: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. J. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keselman HJ, Miller CW, Holland B. Many tests of significance: New methods for controlling Type I Errors. Psychol Methods. 2011;16(4):420–431. doi: 10.1037/a0025810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lasa L, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Diez-Manrique FJ, Dowrick CF. The use of the Beck Depression Inventory to screen for depression in the general population: A preliminary analysis. J Affect Disord. 2000;57(3):261–5. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mayou RA, Ehlers A, Hobbs M. Psychological debriefing for road traffic accident victims: Three-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:589–93. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.6.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bisson JI, Jenkins PL, Alexander J, Bannister C. Randomised controlled trial of psychological debriefing for victims of acute burn trauma. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:78–81. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Emotional processing of fear: exposure to corrective information. Psychol Bull. 1986;99(1):20–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roy-Byrne PP, Russo J, Michelson E, Zatzick D, Pitman RK, Berliner L. Risk factors and outcome in ambulatory assault victims presenting to the acute emergency department setting. Implications for secondary prevention studies in PTSD. Depress Anxiety. 2004;19(2):77–84. doi: 10.1002/da.10132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McFarlane AC. The longitudinal course of posttraumatic morbidity: the range of outcomes and their predictors. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;176:30–39. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zatzick DF, Koepsell T, Rivara FP. Using target population specification, effect size, and reach to estimate and compare the population impact of two PTSD preventive interventions. Psychiatry. 2009;72(4):346–359. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2009.72.4.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.