Abstract

Background

A study at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) Medical Center demonstrated that quality of life in cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) patients is negatively impacted. Whether CLE patients in other geographic locations have similar quality of life is unknown.

Objective

We sought to compare quality of life indicators between CLE patients at the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center at Dallas and UPenn.

Methods

248 CLE patients at UTSW (N=91) and UPenn (N=157) completed the Skindex-29+3 and Short Form-36 (SF-36) surveys related to quality of life. Additional information including demographics, presence of SLE, and disease severity were collected from UTSW CLE patients.

Results

Most Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 sub-domain scores between UTSW and UPenn CLE patients were similar. However, UTSW CLE patients were significantly more affected in the functioning and lupus-specific Skindex-29+3 domains, and physical functioning, role-physical, and general health SF-36 subscales than UPenn CLE patients (p<0.05). Factors related to poor quality of life in UTSW CLE patients include gender, income, education, presence of SLE, and skin disease activity.

Conclusions

Most quality of life indicators were similar between the two CLE populations. Differences in psychosocial behavior, and a larger proportion of SLE patients and females in the UTSW group likely attributed to differences in a minority of Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 sub-domains. Capturing data from CLE populations in different locations provides a more thorough picture of the quality of life that CLE patients experience on a daily basis with special attention to quality of life issues in select CLE patients.

Keywords: cutaneous lupus erythematosus, quality of life, Short Form-36, Skindex-29, Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index, multi-center

INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous involvement is one of the most frequent clinical complaints of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and has been found to occur in up to 70% of patients during the course of the disease.1 Based on the Gilliam and Sontheimer classification,2 CLE can be subclassified into acute cutaneous LE (ACLE), subacute cutaneous LE, and chronic cutaneous LE. Each subtype is associated with histological characteristics specific to LE3 and varying prognostic features (e.g. progression to SLE).4–8

The degree to which CLE affects a patient's quality of life has not been extensively studied. In general, CLE is regarded as having a less severe course and better prognosis than SLE. However, CCLE and SCLE can last many years and may lead to severe vocational disability and limited quality of life similar to its systemic counterpart.9–10 A recent cross-sectional study including 157 CLE patients supported this observation.11 Using two previously validated quality of life questionnaires, a University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) study showed that CLE patients had poor quality of life that was worse or similar to other common dermatologic (e.g. acne, non-melanoma skin cancer) and medical conditions (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, recent myocardial infarction). Furthermore, a follow-up analysis of smokers and non-smokers within the same CLE population demonstrated worse quality of life indices in current smokers.12 A survey of 71 Brazilian CLE patients showed that those with active lesions or alopecia were more likely to have diminished quality of life.13 However, all of these studies were limited to one medical center.

By means of a collaborative, web-based database,14 we sought to compare quality of life in CLE patients from UPenn and University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center using the Skindex-29+3 and Short Form-36 (SF-36) questionnaires. We hypothesized that the Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 sub-domain scores would not be significantly different between the two CLE populations. This would support the expansion of the current web-based database in order to include CLE cohorts in other locations and facilitate larger investigations using similar outcome measures. Furthermore, this multi-center cross-sectional study represents the first of its kind that compares quality of life data from two different CLE populations using a web-based database. We also sought to identify additional clinical and demographic factors that negatively influence quality of life in the UTSW CLE patient population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population

A multi-center cross-sectional study to determine quality of life in patients with clinical and/or pathologic evidence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) was performed at University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Medical Center in Dallas, TX, and University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) in Philadelphia, PA, from January 2007 to June 2011. Patients were eligible for enrollment upon completion of two required questionnaires on quality of life (Skindex-29+315 and Short Form (SF)-3616–17 surveys) and were enrolled regardless of treatment status. Patients who did not complete the Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 questionnaires, or who had a diagnosis other than CLE, were excluded. Additional patient information included demographics, income, educational level, presence or absence of SLE, smoking, and clinical features such as the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index (CLASI)18 and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity index (SLEDAI).19

All patients were 18 years or older and were enrolled after signing institutional review board-approved consent forms.

Skindex-29+3

Skindex-29 is a previously validated skin-specific quality of life survey,15 which consists of 29 questions that are used to calculate three subscales, including symptoms, emotions, and functioning. A fourth subscale was added consisting of three questions to assess lupus-specific concerns (such as photosensitivity, and alopecia).11,14 Scores range from 0–100 with higher scores indicating poorer quality of life.

SF-36

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) measures responses to eight subscales relating to general health including physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health.16–17 Each score is transformed onto a 0–100 scale and converted into a norm-based score (using a mean of 50 and a SD deviation of 10 for the US general population), allowing for comparison of scores to other medical conditions (e.g. clinical depression, acute myocardial infarction, diabetes type II, hypertension, and congestive heart failure).20–22 Contrary to the Skindex-29+3, higher scores for the SF-36 are associated with better quality of life.

Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index (CLASI)

The CLASI is a clinically validated tool that grades both clinical activity and damage in CLE patients.18 With a range of 0 to 70, the CLASI activity score is based on erythema, scaling, mucous membrane involvement, and alopecia. With a range of 0 to 56, the CLASI damage score is measured by dyspigmentation and scarring. Activity and damage scores are given for each body part, with greater emphasis on face and scalp. Disease severity in CLE patients were classified as mild (CLASI activity score: 0–9), moderate (10–20), or severe (≥21).23

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 82 patients at UTSW was calculated in order to detect a difference of 0.1 times the standard deviation in the mean score, with a two-sided type I error of 0.05 and a power of 0.8, compared with 157 patients at UPenn. Patient characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics, and comparisons of continuous and categorical variables were performed using two-sample t-tests, chi-square tests or Fisher's exact tests. Two-sample t-tests were used to compare means among UTSW and UPenn patients for all four Skindex-29+3 and eight SF-36 subscales. Combined Skindex-29 and SF-36 (mean) subscale scores for all CLE patients (UTSW and UPenn) were compared with other dermatologic and medical conditions using either two-sample (Skindex-29) or one-sample (SF-36) t-tests. Associations with quality of life were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's test for multiple comparisons, correlation (Spearman), and t-tests where appropriate. Two-sided, unadjusted p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

More than 90% of CLE patients at UTSW (N=91 accepted) and UPenn (N=157 accepted), who were invited to participate, completed the questionnaires and were enrolled in this multi-center cross-sectional quality of life study (Table 1). CLE patients in both populations were predominantly female. Significantly more CLE African American (p=0.0002) and Hispanic patients (p=0.01) and fewer CLE Caucasian (p<0.0001) patients were enrolled at UTSW than UPenn. Localized discoid LE (DLE) patients were significantly more common at UTSW than UPenn (p=0.02), while similar rates of generalized DLE, SCLE, and ACLE patients were seen. A higher percentage of UTSW CLE patients demonstrated mild disease than UPenn CLE patients (p=0.01) with the opposite trend seen with severe disease (p=0.02). More UTSW CLE patients met specific SLE criteria including malar rash (p=0.03), discoid rash (p=0.006), hematological disorder (p<0.0001), anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) (p<0.0001), and immunological disorder (p=0.01) than UPenn patients. Additionally, UTSW CLE patients were more likely to be on topical steroids, antimalarials, or immunosuppressive agents (e.g. azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate) compared with UPenn CLE patients (p<0.05). Duration of disease and rates of other autoimmune/rheumatic diseases were similar between the UTSW and UPenn groups.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| UTSW (N=91) | UPenn (N=157) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | p-value* | |

| Gender, N (%) | |||

| Male | 10 (11) | 27 (17) | 0.18 |

| Female | 81 (89) | 130 (83) | |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 34 (37) | 107 (68) | <0.0001 |

| African-American | 45 (49) | 41 (26) | 0.0002 |

| Asian | 1 (1) | 7 (4) | 0.26** |

| Hispanic/Latino | 7 (8) | 2 (1) | 0.01** |

| Other | 4 (4)§ | 0 (0) | 0.02** |

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 45 (13) | 47 (14) | 0.18 |

| Disease Duration (yr), mean (SD) ◊ | 8 (8) | 8 (8) | 0.91 |

| Lupus Subtype, N (%) | |||

| Generalized DLE | 20 (22) | 23 (15) | 0.15 |

| Localized DLE | 34 (37) | 36 (23) | 0.02 |

| Tumid | 4 (4) | 12 (8) | 0.43** |

| Chilblains | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.05** |

| Lupus panniculitis | 0 (0) | 5 (3) | 0.16** |

| SCLE | 13 (14)† | 38 (24) | 0.06 |

| ACLE | 10 (11) | 8 (5) | 0.09 |

| Multiple subtypes | 7 (8) | 11 (7) | 0.84 |

| Lupus nonspecific | 0 (0) | 13 (8) | 0.003** |

| Other | 0 (0) | 11 (7) | 0.008** |

| Disease Severity, N (%) ‡ | |||

| Mild | 73 (80) | 103 (68) | 0.01 |

| Moderate | 15 (16) | 30 (20) | 0.73 |

| Severe | 3 (3) | 19 (13) | 0.02** |

| SLE, N (%) | |||

| Present | 45 (49) | 63 (40) | 0.15 |

| Absent | 46 (51) | 94 (60) | |

| SLE Criteria, N (%) | |||

| Malar | 31 (34) | 34 (22) | 0.03 |

| Discoid | 54 (59) | 39 (25) | 0.006 |

| Photosensitivity | 72 (79) | 81 (52) | 0.24 |

| Oral ulcers | 33 (36) | 42 (27) | 0.12 |

| Arthritis | 26 (29) | 47 (30) | 0.82 |

| Serositis | 11 (12) | 10 (6) | 0.13 |

| Renal disorder | 10 (11) | 18 (11) | 0.91 |

| Neurological disorder | 0 | 6 (4) | 0.09** |

| Hematological disorder | 48 (53) | 8 (5) | <0.0001 |

| ANA | 63 (69) | 47 (30) | <0.0001 |

| Immunological disorder | 33 (36) | 34 (22) | 0.01 |

| Other Autoimmune/Rheumatic Disease, N (%) | 15 (16) | 26 (17) | 1 |

| Presence of Facial Lesions, N (%) | 51 (56) | 93 (60) | 0.62 |

| Alopecia, N (%) | 46 (51) | 67 (43) | 0.23 |

| Current Therapy, N (%) ‡‡ | |||

| Topical steroids | 28 (31) | 27 (17) | 0.01 |

| Antimalarials | 71 (78) | 93 (59) | 0.002 |

| Immunosuppressive agents | 32 (35) | 34 (22) | 0.02 |

| Thalidomide | 0 | 4 (3) | 0.30** |

| Prednisone | 25 (27) | 36 (23) | 0.43 |

| Intralesional steroids | 3 (3) | 14 (9) | 0.12** |

| No therapy | 14 (15) | 41 (26) | 0.05 |

p-values were calculated using two-sample t-tests (continuous variables) or chi-square tests (categorical variables) unless indicated.

p-values were calculated using Fisher exact tests.

Includes persons of mixed ethnicity and one American Indian/Alaskan Native

Includes one patient with drug-induced subacute lupus erythematosus

Five patients with disease severity were not available from the University of Pennsylvania CLE cohort.

Patients taking multiple medications were counted more than once.

Duration of disease not available for 56 patients (UTSW, N=14 and UPenn, N=44).

Abbreviations: ACLE = acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus; ANA = anti-nuclear antibody; DLE = discoid lupus erythematosus; SCLE = subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus; SD = standard deviation; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus; UPenn = University of Pennsylvania; UTSW = University of Texas Southwestern

Skindex-29+3 scores of UTSW and UPenn CLE patients

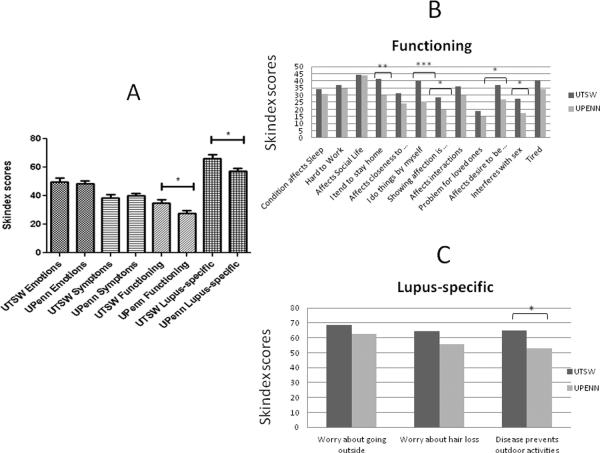

We first focused on skin-specific quality of life measures by comparing scores from Skindex-29+3 questionnaires that were administered to CLE patients at UTSW and UPenn (with higher scores indicating poorer quality of life). Both CLE groups were similarly affected in the emotions and symptoms sub-domains (emotions: 50±29 (UTSW) vs. 48±28 (UPenn), p=0.77; symptoms: 39±22 (UTSW) vs. 40±23 (UPenn), p=0.65). However, UTSW CLE functioning [35±26] and lupus-specific [66±29] sub-domains were significantly more affected than UPenn's CLE functioning [28±25, p=0.04] and lupus-specific [57±28, p=0.02] sub-domains (Fig. 1a). Within the functioning sub-domain, UTSW CLE patients tended to stay home [41±33] and do things on their own [40±35] significantly more often than UPenn CLE patients [30±34, p=0.01, and 25±32, p=0.0007, respectively]. They also expressed greater difficulty with showing affection [28±35] compared with UPenn CLE patients [20±28, p=0.04], and showed greater effect of the disease on their desire to be with others [37±35 (UTSW) vs. 27±32 (UPenn), p=0.02], and on their sex lives [27±36 (UTSW) vs. 17±28 (UPenn), p=0.02] (Fig. 1b). Within the lupus-specific sub-domain, UTSW CLE scores were significantly higher [64±36] than UPenn's [53±36, p=0.01] when patients were questioned how often their skin disease prevented them from doing outdoor activities (Fig. 1c).

Fig 1.

Skindex-29+3 scores in UTSW and UPenn CLE patients. (a) Mean scores for Skindex-29+3 emotions, symptoms, functioning and lupus-specific sub-domains between UTSW (N=91) and UPenn (N=157) CLE patients were calculated. (b) and (c), Mean scores from individual questions within the Skindex-29+3 functioning (b) and lupus-specific sub-domains (c) between UTSW and UPenn CLE patients were calculated. Two-tailed, two-sample t-tests were performed to determine statistical significance. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.005, ***: p<0.0005

Abbreviations: CLE = Cutaneous lupus erythematosus; UPenn = University of Pennsylvania; UTSW = University of Texas Southwestern

SF-36 scores of UTSW and UPenn CLE patients

To assess how CLE impacted global health of both patient populations, we evaluated results from SF-36 questionnaires. Contrary to the Skindex-29+3, lower scores for the SF-36 are associated with better quality of life. Mean SF-36 subscale scores relating to bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health at both institutions were similar, while SF-36 subscale scores in the physical functioning, role-physical, and general health sub-domains were significantly poorer in UTSW CLE patients compared with UPenn patients (p<0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean SF-36 subscale scores between UTSW and UPenn CLE patients

| SF-36 subscale | UTSW CLE mean (SD) | UPenn CLE mean (SD) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 41 (13) | 46 (12) | 0.001 |

| Role-physical | 41 (13) | 45 (12) | 0.03 |

| Bodily pain | 49 (12) | 51 (11) | 0.23 |

| General health | 39 (12) | 42 (11) | 0.03 |

| Vitality | 44 (11) | 46 (11) | 0.20 |

| Social functioning | 42 (13) | 44 (12) | 0.11 |

| Role-emotional | 42 (14) | 45 (14) | 0.10 |

| Mental health | 45 (10) | 45 (12) | 0.96 |

p-values were calculated using two-sample t-tests.

Abbreviations: CLE = cutaneous lupus erythematosus; SD = standard deviation; SF-36 = Short Form-36; UPenn = University of Pennsylvania; UTSW = University of Texas Southwestern

UTSW and UPenn CLE patients versus other skin diseases and medical conditions

After combining Skindex-29 scores from both CLE populations, CLE patients were still among the most severely affected compared with other dermatological diseases such as acne, psoriasis, eczema, rosacea, and non-melanoma skin cancer/actinic keratosis (Supplementary Table 1).11 SF-36 scores from both CLE populations were lower in all sub-domains (except for bodily pain and mental health) compared with those from UPenn CLE population alone.11 The aggregated SF-36 scores resulted in over 70% of sub-domains showing significantly worse scores in CLE compared with hypertensive, diabetic, and recent myocardial infarction patients (Supplemental Table 2).

Factors related to quality of life in UTSW patients

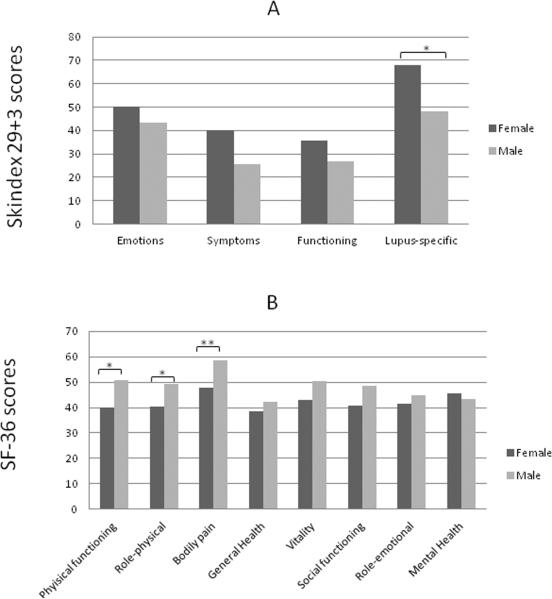

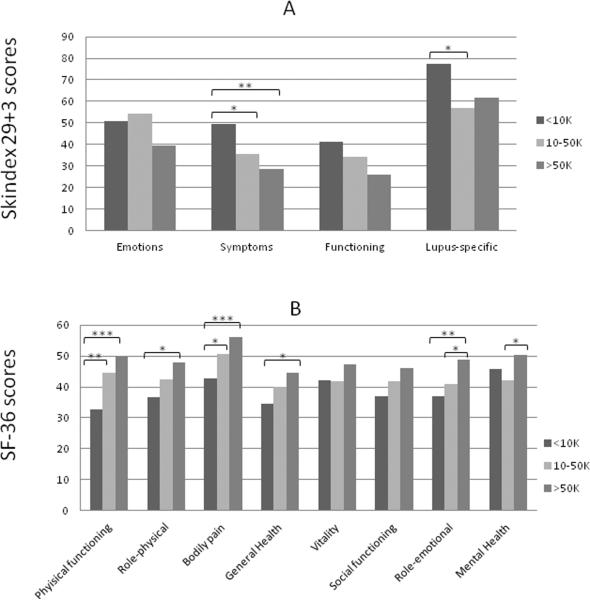

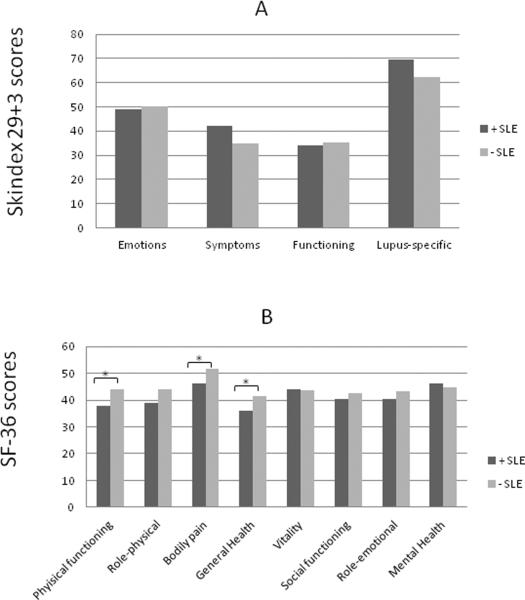

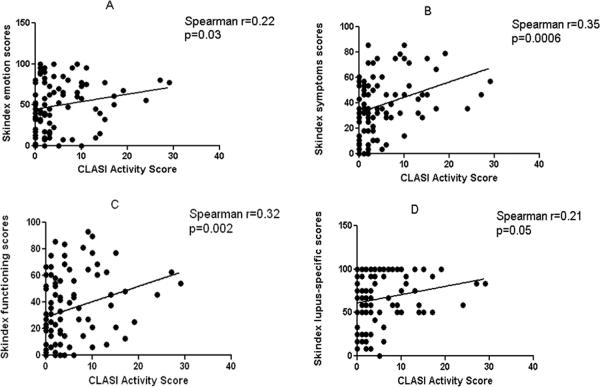

Within the UTSW CLE population, we analyzed numerous clinical and demographic factors (including gender, ethnicity, income, education, presence and absence of SLE, CLE subtype, disease severity, and smoking history) to determine association with poor quality of life, as determined by Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 scores. Female gender (N=81) was generally associated with poor quality of life in all four Skindex-29+3 sub-domains with statistical significance in the lupus-specific sub-domain (p=0.04) (Fig. 2a). Similarly, significant differences between female and male CLE subsets were seen in SF-36 physical functioning (p=0.01), role-physical (p=0.05), and bodily pain (p=0.005) subscales (Fig. 2b). CLE patients earning <$10,000 (N=26) were associated with worse Skindex-29+3 symptoms (p=0.002) and lupus-specific (p=0.02) sub-domain scores compared with those earning between $10,000 and $50,000 (N=26) and >$50,000 (N=21) (Fig. 3a). Likewise, CLE patients earning <$10,000 showed significant impairment in SF-36 physical functioning (p<0.0001), role-physical (p=0.01), bodily pain (p=0.0002), general health (p=0.02), and role-emotional (p=0.01) subscales compared with those earning greater than $10,000 (Fig. 3b). CLE patients with a graduate level education (N=9) had better scores in all Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 sub-domains than those with a high school (N=39) or college education (N=30) with statistical significance in SF-36 physical functioning scores (p=0.02) (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). CLE patients with SLE (N=45) and without SLE (N=46) were similarly affected across all Skindex-29+3 sub-domains (Fig. 4a). On the contrary, CLE patients with SLE fared significantly worse than CLE patients without SLE in terms of SF-36 physical functioning (p=0.03), bodily pain (p=0.02), and general health (p=0.03) sub-domain scores (Fig. 4b). Increased disease severity, as measured by the CLASI activity score, correlated with worse quality of life for all four Skindex-29+3 sub-domains (rsp=0.21–0.35, p<0.05) (Fig. 5a–d). Ethnicity, disease subtype, SLE disease activity, and smoking history did not have a significant impact on Skindex-29+3 or SF-36 subscale scores in UTSW CLE patients (data not shown).

Fig 2.

Gender and Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 sub-domain scores in UTSW CLE patients. (a), Mean scores and standard deviations (SD) for Skindex-29+3 emotions, symptoms, functioning and lupus-specific sub-domains in UTSW CLE female (N=81) and male (N=10) patients were calculated. (b), Mean scores and SDs for SF-36 physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health sub-domains were calculated in UTSW CLE female and male patients. Two-tailed, two-sample t-tests were performed to determine statistical significance. *: p<0.05, **: p≤0.005

Abbreviations: BP= Bodily pain; CLE = Cutaneous lupus erythematosus; GH= General Health; MH= Mental Health; PF= Physical functioning; RE= Role-emotional; RP=Role-physical; SD = Standard deviation; SF-36 = Short-Form 36; SF=Social functioning; UTSW = University of Texas Southwestern; V= Vitality

Fig 3.

Income and Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 sub-domain scores in UTSW CLE patients. (a), Mean scores and standard deviations (SD) for Skindex-29+3 emotions, symptoms, functioning and lupus-specific sub-domains in UTSW CLE patients earning <10K (N=26), 10–50K (N=26), and >50K (N=21) were calculated. (b), Mean scores and SDs for SF-36 physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health sub-domains were calculated in these same three income groups. Income information was not available for 18 of 91 UTSW CLE patients. One-way analysis of variance with Tukey's test for multiple comparisons was performed to determine statistical significance. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.005, ***: p<0.0005

Abbreviations: BP= Bodily pain; CLE = Cutaneous lupus erythematosus; GH= General Health; MH= Mental Health; PF= Physical functioning; RE= Role-emotional; RP=Role-physical; SD = Standard deviation; SF-36 = Short-Form 36; SF=Social functioning; UTSW = University of Texas Southwestern; V= Vitality

Fig 4.

Presence or absence of SLE and Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 sub-domain scores in UTSW CLE patients. (a), Mean scores and standard deviations (SD) for Skindex-29+3 emotions, symptoms, functioning and lupus-specific sub-domains in UTSW CLE patients with (+SLE) (N=45) and without SLE (−SLE) (N=46) were calculated. (b), Mean scores and SDs for SF-36 physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health sub-domains were calculated for these two groups. Two-tailed, two-sample t-tests were performed to determine statistical significance. *: p<0.05

Abbreviations: BP= Bodily pain; CLE = Cutaneous lupus erythematosus; GH= General Health; MH= Mental Health; PF= Physical functioning; RE= Role-emotional; RP=Role-physical; SD = Standard deviation; SF-36 = Short-Form 36; SF=Social functioning; UTSW = University of Texas Southwestern; V= Vitality

Fig 5.

CLASI activity and Skindex-29+3 sub-domain scores. Relationships between CLASI activity scores and mean Skindex-29+3 sub-domain scores (emotions (a), symptoms (b), functioning (c) and lupus-specific (d)) were assessed via correlation plots. Spearman's correlation coefficient and corresponding p-values were calculated.

Abbreviations: CLASI = Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index

DISCUSSION

We have performed the first multi-center cross-sectional study assessing quality of life in two geographically distinct CLE populations. Our results show that quality of life between UTSW and UPenn CLE groups are largely comparable, suggesting that quality of life indicators (Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 surveys) in CLE patients are mostly generalizable. However, UTSW CLE patients were significantly more affected in the Skindex-29+3 functioning and lupus-specific sub-domains, and SF-36 physical functioning, role-physical, and general health subscales than UPenn CLE patients. Correlates of poorer quality of life included female gender, low income, low education, presence of SLE, and increased disease activity in UTSW CLE patients.

Despite contrasting ethnic compositions of both CLE cohorts, our study demonstrated mostly similar Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 sub-domain scores between CLE patients at UTSW and UPenn. This finding reinforces the reproducibility of quality of life indicators in a larger CLE population and emphasizes the negative affect that CLE imposes on quality of life compared with other severe dermatologic and medical conditions (Supplemental Tables 1–2). Accordingly, as part of the first multi-center study to reproduce significant quality of life indicators in CLE patients, our results support the expansion of the current web-based database in order to include other CLE cohorts and support larger investigations using similar outcome measures to determine impact of disease, even longitudinally.14 This would follow the model of the multi-center Lupus in Minorities: Nature vs. Nurture (LUMINA) cohort. LUMINA, the result of a collaborative effort between four academic institutions, is a longitudinal cohort study of SLE patients with the goal of determining predictors of disease course and outcomes.24

While most quality of life indicators were similar between both CLE patients, there were some sub-domains in the Skindex-29 and SF-36 surveys with significant differences. This underscores the importance of assessing quality of life in CLE populations from different geographic locations which account for variations in quality of life measures. Differences in psychosocial behavior (e.g. self-esteem, social interactions) appear to account for variations in Skindex-29+3 functioning and lupus-specific sub-domains between UTSW and UPenn CLE patients (Fig. 1a). Variations in psychosocial behavior, particularly lower self-esteem and increased social withdrawal in the UTSW CLE patients, can be inferred from responses to questions specific to the functioning sub-domain (Fig. 1b). Persistent concern for subsequent disease flares due to outdoor activities has been shown to reduce quality of life in CLE patients even after disease activity and damage has improved.25 The southern location of Dallas (compared with Philadelphia) predisposes UTSW CLE patients to receive higher quantities of ultraviolet radiation throughout the year26 and may be responsible for increased anxiety and avoidance of outdoor activity and tendency to stay home (Fig. 1c). While oral ulcers, facial lesions, and alopecia have also been associated with poor interpersonal relationships,11,13 appearance, self-image and quality of life in lupus patients, there was no significant difference in these factors between UTSW and UPenn CLE populations (Table 1).

Increased prevalence of females and SLE patients in the UTSW CLE population may explain worse SF-36 physical functioning, role-physical, and general health sub-domain scores versus the UPenn CLE population (Table 1). Females in the UTSW cohort had worse SF-36 scores in the physical functioning and role-physical sub-domains compared with males (Fig. 2b). Correspondingly, UTSW CLE patients with SLE fared significantly worse than UTSW CLE patients without SLE in the SF-36 physical functioning, bodily pain, and general health sub-domains (Fig. 4b).

Previously reported associations with poor quality of life in CLE patients include female gender, generalized disease, severe disease, distribution of lesions, and younger age.11 In addition to the presence of SLE, we found that low income and education levels were also predictive of poor quality of life in our UTSW CLE patients. This emphasized the importance of poor socioeconomic status in the outcome of chronic disorders such as lupus.27 We also demonstrated a linear correlation with CLASI activity scores and Skindex-29+3 scores, thereby strengthening the previous association of CLE patients with severe disease having poor quality of life.11 Unlike our colleagues at UPenn,11–12 we did not observe a difference in quality of life among disease subtypes or smoking history.

While clinicians may be more apt to treat skin disease activity in CLE patients in order to improve their quality of life, other factors can also impact CLE patients' well-being.25,28 Specifically, cosmetic considerations, concern for subsequent flares, and impaired outdoor activities have been shown to reduce quality of life even when lupus disease becomes less active.25,29 As a result, findings from this study and the literature imply that therapeutic goals should extend beyond improving skin disease activity and emphasize the need to identify and/or provide rehabilitation for these aforementioned factors that may contribute to poor quality of life. Special consideration may be warranted for specific CLE populations. For patients who are female, have SLE, or come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, asking questions about self-esteem, overall health, and/or employment will allow providers to address these deficiencies by making appropriate referrals to other physicians (e.g. rheumatologists, psychiatrists), patient support groups, and social workers. Additionally, our data underscores the importance of studying populations from different geographic locations, which showed differences in psychosocial behavior, including increased social withdrawal in the UTSW CLE cohort, as shown by their avoidance of outdoor activities and preference to stay home (Fig. 1b and 1c). Thus, closer attention to quality of life may be necessary for CLE patients who live in warmer climates, including asking questions about outside or daily activities, and providing practical information on the disease via support groups.

Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional nature. Because socioeconomic status was not available in the UPenn CLE population, we could not determine whether socioeconomic status differences contributed to the diversity in quality of life scores. Future longitudinal studies are planned to collect this variable in both populations and adjust for this and other variables (e.g. disease severity, gender, SLE prevalence) to determine if differences in quality of life measures persist. As both institutions are tertiary care centers that garner referrals from outside practitioners, the severity of quality of life may be overestimated in both CLE populations. A larger collaborative study, including CLE patients from community physicians, can be supported by this web-based database.

In conclusion, we have shown that Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 subclass scores between UTSW and UPenn CLE patients are largely comparable. Differences in a minority of sub-domains were likely attributed to variations in psychosocial behavior, presence of SLE, and gender. The combined quality of life data strengthens the notion that CLE patients are among the most severely impaired in terms of quality of life when compared with other common dermatologic and medical conditions. Besides female gender and skin disease activity, income, education, and presence of SLE were shown to be additional risk factors for poor quality of life in CLE patients. An interdisciplinary approach incorporating the use of trained healthcare personnel, patient support groups, and social workers providing behavioral and medical interventions may prove useful in select CLE patients.

Supplementary Material

Education and Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 sub-domain scores in UTSW CLE patients. (a), Mean scores and standard deviations (SD) for Skindex-29+3 emotions, symptoms, functioning and lupus-specific sub-domains in UTSW CLE patients with high school or less (N=39), college or equivalent (N=30), and graduate (N=9) education were calculated. (b), Mean scores and SDs for SF-36 physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health sub-domains were calculated in these three groups. Education information was not available for 13 of 91 UTSW CLE patients. One-way analysis of variance with Tukey's test for multiple comparisons was performed to determine statistical significance. *: p<0.05.

Abbreviations: BP= Bodily pain; CLE = Cutaneous lupus erythematosus; GH= General Health; MH= Mental Health; PF= Physical functioning; RE= Role-emotional; RP=Role-physical; SD = Standard deviation; SF-36 = Short-Form 36; SF=Social functioning; UTSW = University of Texas Southwestern; V= Vitality

What is already known about this topic? What does this study add?

Quality of life in cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) patients is negatively impacted.

Quality of life indicators were mostly similar in CLE patients at two locations.

Female gender, low socioeconomic status, systemic disease, and worse skin disease activity are related to poor quality of life.

Special attention to quality of life may benefit CLE patients residing in warmer climates, who are more likely to avoid outdoor activities.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Julie Song, Sandra Victor, Azza Mutwally, and Valerie Branch for aiding in the recruitment of the UTSW CLE patients. We are indebted to Rose Ann Cannon for her help in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding/Support: This project was funded in part by NIH CTSA Grant #UL1 RR024982 and the American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Bridge Funding Grant (BFC).

Abbreviations

- ACLE

acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- ANA

antinuclear antibody

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- CLASI

Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity

- CLE

cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- CCLE

chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- DLE

discoid lupus erythematosus

- LE

lupus erythematosus

- SCLE

subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- SF-36

Short Form-36

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- SLEDAI

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity index

- UPenn

University of Pennsylvania

- UTSW

University of Texas Southwestern

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Chong is an investigator for Celgene Corporation and Amgen Incorporated. Dr. Werth is a consultant for Pfizer Incorporated, Medimmune, Genentech Incorporated, Novartis International AG, Celgene Corporation, Stiefel Laboratories, Incorporated, Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Amgen Incorporated, and Astion Pharma. Dr. Werth has also received grants and honoraria from Celgene Corporation, Amgen Incorporated, and Astion Pharma.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patel P, Werth V. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a review. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:373–85. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilliam JN, Sontheimer RD. Distinctive cutaneous subsets in the spectrum of lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:471–5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)80261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinkus H. Lichenoid tissue reactions. A speculative review of the clinical spectrum of epidermal basal cell damage with special reference to erythema dyschromicum perstans. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:840–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.107.6.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sontheimer RD. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a decade's perspective. Med Clin North Am. 1989;73:1073–90. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callen JP. Chronic Cutaneous Lupus-Erythematosus - Clinical, Laboratory, Therapeutic, and Prognostic Examination of 62 Patients. Archives of Dermatology. 1982;118:412–416. doi: 10.1001/archderm.118.6.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothfield N, March CH, Miescher P, et al. Chronic Discoid Lupus Erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 1963;269:1155–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196311282692201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Millard LG, Rowell NR. Abnormal laboratory test results and their relationship to prognosis in discoid lupus erythematosus. A long-term follow-up study of 92 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1055–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prystowsky SD, Gilliam JN. Discoid lupus erythematosus as part of a larger disease spectrum. Correlation of clinical features with laboratory findings in lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:1448–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tebbe B, Orfanos CE. Epidemiology and socioeconomic impact of skin disease in lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1997;6:96–104. doi: 10.1177/096120339700600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Quinn SE, Cole J, Many H. Problems of disability and rehabilitation in patients with chronic skin diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein R, Moghadam-Kia S, Taylor L, et al. Quality of life in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:849–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piette EW, Foering KP, Chang AY, et al. Impact of Smoking in Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:317–22. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferraz LB, Almeida FA, Vasconcellos MR, et al. The impact of lupus erythematosus cutaneous on the Quality of life: the Brazilian-Portuguese version of DLQI. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:565–70. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-2638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moghadam-Kia S, Chilek K, Gaines E, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of a collaborative Web-based database for lupus erythematosus-associated skin lesions: prospective enrollment of 114 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:255–60. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, et al. Skindex, a quality-of-life measure for patients with skin disease: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:707–13. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12365600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–63. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albrecht J, Taylor L, Berlin JA, et al. The CLASI (Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index): an outcome instrument for cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:889–94. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, et al. Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:630–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart AL, Ware JE. Measuring functioning and well-being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Duke University Press; Durham, NC: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarlov AR, Ware JE, Jr, Greenfield S, et al. The Medical Outcomes Study. An application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. Jama. 1989;262:925–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.7.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells KB, Burnam MA, Rogers W, et al. The course of depression in adult outpatients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:788–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820100032007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein RS, Morganroth PA, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus and the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index instrument. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2010;36:33–51. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alarcon GS. Lessons from LUMINA: a multiethnic US cohort. Lupus. 2008;17:971–6. doi: 10.1177/0961203308094359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaines E, Bonilla-Martinez Z, Albrecht J, et al. Quality of life and disease severity in a cutaneous lupus erythematosus pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1061–2. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.8.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eide MJ, Weinstock MA. Association of UV index, latitude, and melanoma incidence in nonwhite populations--US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, 1992 to 2001. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:477–81. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Roseman JM, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XIX. Natural history of the accrual of the American College of Rheumatology criteria prior to the occurrence of criteria diagnosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:609–15. doi: 10.1002/art.20548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finlay AY. Quality of life measurement in dermatology: a practical guide. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:305–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aberer E. Epidemiologic, socioeconomic and psychosocial aspects in lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2010;19:1118–24. doi: 10.1177/0961203310370348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Education and Skindex-29+3 and SF-36 sub-domain scores in UTSW CLE patients. (a), Mean scores and standard deviations (SD) for Skindex-29+3 emotions, symptoms, functioning and lupus-specific sub-domains in UTSW CLE patients with high school or less (N=39), college or equivalent (N=30), and graduate (N=9) education were calculated. (b), Mean scores and SDs for SF-36 physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health sub-domains were calculated in these three groups. Education information was not available for 13 of 91 UTSW CLE patients. One-way analysis of variance with Tukey's test for multiple comparisons was performed to determine statistical significance. *: p<0.05.

Abbreviations: BP= Bodily pain; CLE = Cutaneous lupus erythematosus; GH= General Health; MH= Mental Health; PF= Physical functioning; RE= Role-emotional; RP=Role-physical; SD = Standard deviation; SF-36 = Short-Form 36; SF=Social functioning; UTSW = University of Texas Southwestern; V= Vitality