Abstract

Purpose

The goal of this study was to assess the correlation between the Helicobacter pylori status of patients who underwent curative resection for gastric adenocarcinoma and their prognosis in Eastern societies where H. pylori infection is prevalent.

Methods

Between 2006 and 2007, 192 patients who had a curative resection for the treatment of gastric adenocarcinoma were enrolled in the study. Of these patients, 18 were excluded due to an inexact evaluation of the H. pylori status, thereby leaving 174 patients in the final analysis. Serologic testing for H. pylori was assessed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit for immunoglobulin G, and the histological presence of H. pylori was identified using the Giemsa stain.

Results

Of the 174 patients, 111 patients (63.8%) were confirmed for H. pylori infection. H. pylori status did not correlate with the overall or disease-free survival. For patients with stage III or IV gastric cancer, a positive H. pylori status was a significant predictive factor for recurrence over that of a negative H. pylori status (P = 0.019). Negative H. pylori status was a predictive factor for recurrence in multivariable analysis (relative risk, 2.724; 95 confidence interval, 1.192 to 6.228).

Conclusion

Helicobacter pylori status did not correlate with the clinicopathologic factors of gastric adenocarcinoma. However, a negative Helicobacter pylori status may be a predictive factor for recurrence in patients diagnosed with advanced gastric adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Stomach neoplasm, Prognosis, Survival

INTRODUCTION

Despite the decreasing incidence and mortality of gastric cancer, it remains one of the most common types of cancer and is an important cause of cancer-related deaths in East Asian countries, such as Korea and Japan [1]. A high incidence of gastric cancer in this region has often been attributed to a high rate of Helicobacter pylori infection. In 1994, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified H. pylori as a definite carcinogen based on large-scale epidemiological data [2]. Since the publication the WHO classification, several prospective studies have determined a strong correlation between H. pylori and gastric cancer development and have indicated that the eradication of H. pylori could prevent the progression of gastric cancer [3-5].

The 5-year survival rate has increased to 60 due to a higher rate of early stage diagnoses through mass screening programs in areas of high gastric cancer incidence coinciding with H. pylori epidemic areas. However, greater than 40 of gastric cancer patients are still diagnosed at an advanced stage with a comparatively lower overall survival rate [6]. Patients who are predicted to have a poor prognosis may require aggressive surgical procedures or additional perioperative therapy. Therefore, it is important to understand the factors that are predictive of overall or disease-free survival prior to treatment onset. Although the prognosis for gastric cancer patients is based on the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, there is a range of prognoses within similar stages that cannot be fully explained.

Although a strong correlation between H. pylori and gastric cancer development has been established, the effect of H. pylori status on the prognosis of gastric cancer patients has not been reported in Eastern societies, which are well-known H. pylori endemic areas. Two prospective studies have reported that a negative H. pylori status is associated with an improved prognosis in Western countries [7,8]; however, these results are not globally applicable due to regional differences in H. pylori virulence and gastric cancer incidence [9]. Therefore, the determination of the relationship between gastric cancer patient prognosis and H. pylori status is relevant in areas of high H. pylori prevalence.

Here, we made a plan to collect prospectively the data of gastric cancer patients in Korea, where H. pylori is highly prevalent, to assess the correlation between the H. pylori status of patients who underwent curative resection for the treatment of gastric adenocarcinoma and their prognosis.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ajou University Hospital (Approval No. AJIRB-CRO-06-152). We obtained written informed consent from all participants, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. From January 2006 to December 2007, 192 patients diagnosed with adenocarcinoma based on a gastrofiberoptic biopsy without detectable metastatic lesions in preoperative imaging studies (e.g., computed tomography) were prospectively enrolled. Patients who had a previous gastric resection or had other coincident malignancies were excluded. After enrolment, 18 patients who had unexpected metastatic lesions in the surgical field, had unresectable primary tumours, underwent non-curative resection, or had follow up periods of 3 months or less were dropped from this study. A final total of 174 patients were analysed.

Prior to surgery, a venous blood sample was obtained from each patient for serologic testing. Blood samples were centrifuged to obtain the serum; isolated serum samples were stored at -70℃. Levels of anti H. pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) were assessed qualitatively using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Genedia H pylori ELISA, Green Cross Medical Co., Seoul, Korea). This kit uses an H. pylori antigen extracted from Korean H. pylori strains. A previous study using this kit reported that the sensitivity and specificity in Korean adults were 97.8 and 92.0, respectively [10]. According to the manufacturer's recommendations, the cut-off optical density (450 nm) for the positive presence of H. pylori IgG was 0.405. For the histological diagnosis, non-tumourous tissues were sampled from the antrum and corpus mucosa at least 5 cm from the tumour. Harvested samples were immediately placed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. For the investigation of the histological H. pylori status, the tissues were stained with Giemsa stain and analysed by a pathologist who was unaware of the patient's clinical information.

We defined a positive result for H. pylori infection as when both the serologic and histological results were positive. A patient was classified as negative for H. pylori when either the histological examination or serology was negative. For patients classified as positive for H. pylori, we did not postoperatively prescribe eradication medication.

Surgery was conducted by laparoscopy or an open laparotomy approach. Patients with early stage cancer underwent laparoscopic surgery. After entrance to the abdominal cavity, the entire abdomen was examined to search for unexpected metastatic lesions. Surgery consisted of subtotal or total gastrectomy according to the Japanese Classification for Gastric Carcinoma [11]. Regarding lymphadenectomy, D1 + β for early gastric cancer and D2 for advanced cancer were performed. If it was possible to obtain curability, tumour-invaded organs were resected. Pathologic results were recorded, including the tumour size, location, and type, according to the Lauren and WHO histological classifications, which were categorised into differentiated and undifferentiated types. Tumour invasion, regional lymph node involvement, and pathologic staging were classified according to the TNM guidelines of the Sixth edition of the American Joint of Cancer Committee (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual. In the final pathologic findings, the patients had the tumor invaded into muscle and over, or positive lymph node metastasis received 5-FU-based adjuvant chemotherapy (including single oral fluoropyrimidine like TS-1 and doxifluridine, or combined regimens with fluoropyrimidine and intravenous cisplatin), for a period of 6 months to 1 year if their condition was amenable. All patients in this study were assessed for the recurrence of gastric cancer and death every three to six months through the use of computed tomography, tumor marker expression and physical examination.

A chi-squared test was used to analyse correlations between the clinicopathologic features and H. pylori status. Overall and disease-free survival and H. pylori status were analysed using the Kaplan-Meier test. The factors that predicted cancer recurrence were analysed using the Cox proportional hazard regression model. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

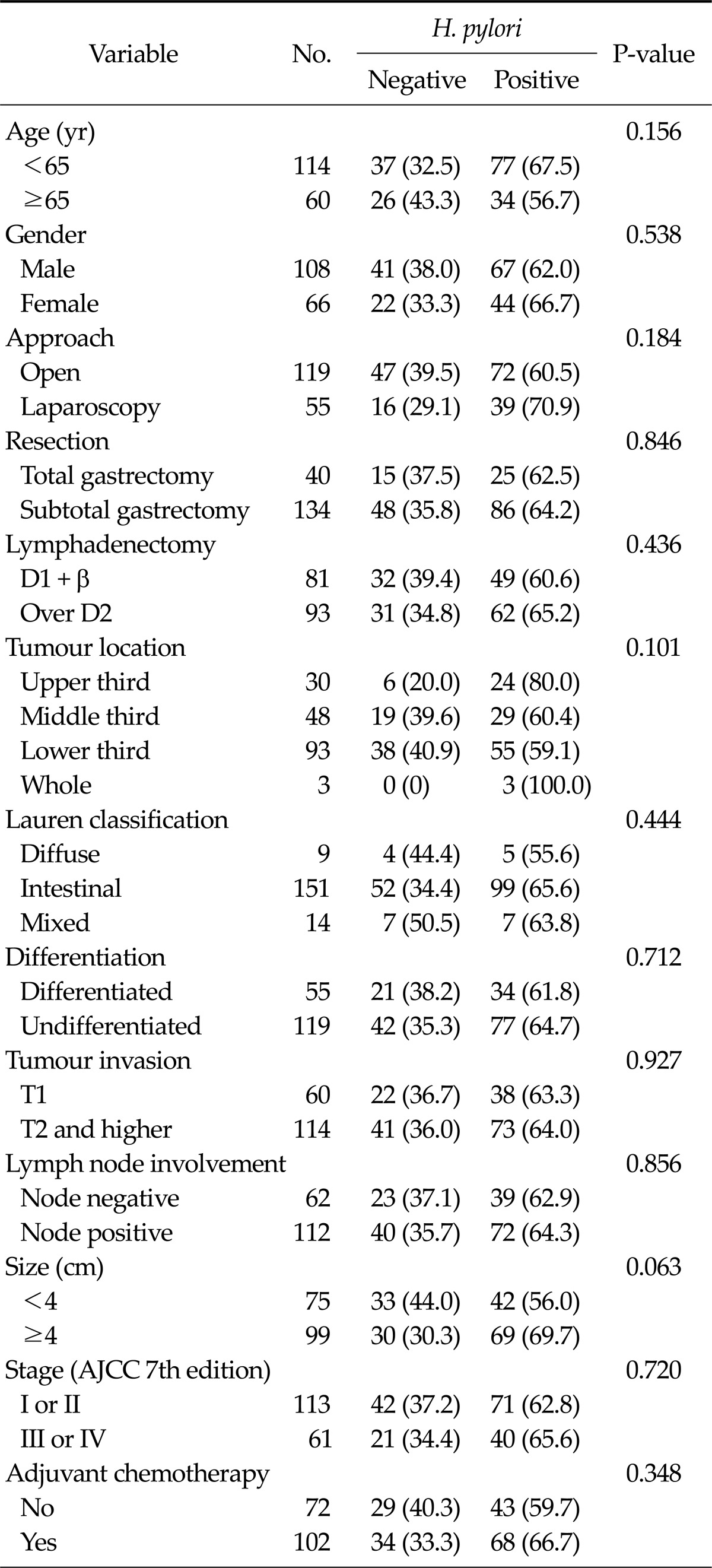

A total of 149 patients (85.5%) were serologically positive for H. pylori IgG. In the histological evaluation, 120 patients (69.0%) were diagnosed with H. pylori infections by both pathologists. Based on these tests, 111 patients (63.8%) showed both serologically and histologically positive results and were confirmed as positive for H. pylori infection. Of the 172 patients, 108 patients (62.7%) were male, and 119 (69.2%) underwent open gastric cancer surgery. A total of 113 patients (65.7%) were pathologically diagnosed as AJCC stage I or II, and 61 patients (34.3%) were stage III or IV. After surgery, 102 patients (59.3%) received adjuvant chemotherapy. No significant variable was identified in the correlation analysis between clinicopathologic features and H. pylori infection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic features according to Helicobactor pylori infection

Values are presented as number (%).

AJCC, American Joint of Cancer Committee.

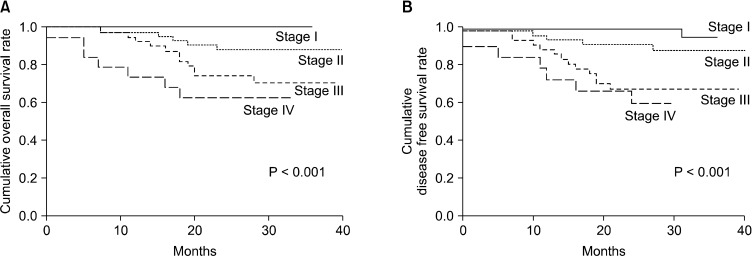

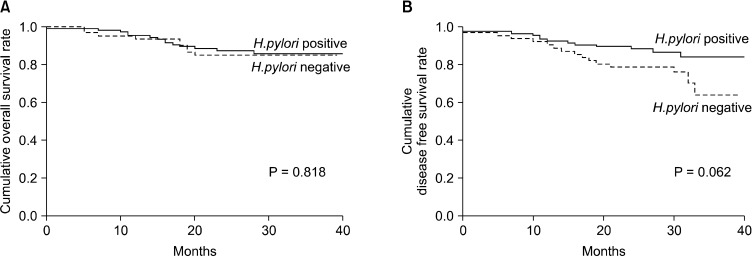

The mean survival time of all patients was 36.4 months, and the mean disease-free survival time was 34.8 months. During the follow-up period, 30 patients had recurrence, and 23 patients died. The overall and disease-free survival of the patients were significantly decreased with increasing tumour staging (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). However, H. pylori infection status did not have a significant effect on the overall or disease-free survival (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Patient survival according to tumor-node-metastasis stage. (A) Overall survival and (B) disease-free survival.

Fig. 2.

Patient survival according to Helicobactor pylori infection status. (A) Overall survival and (B) disease-free survival.

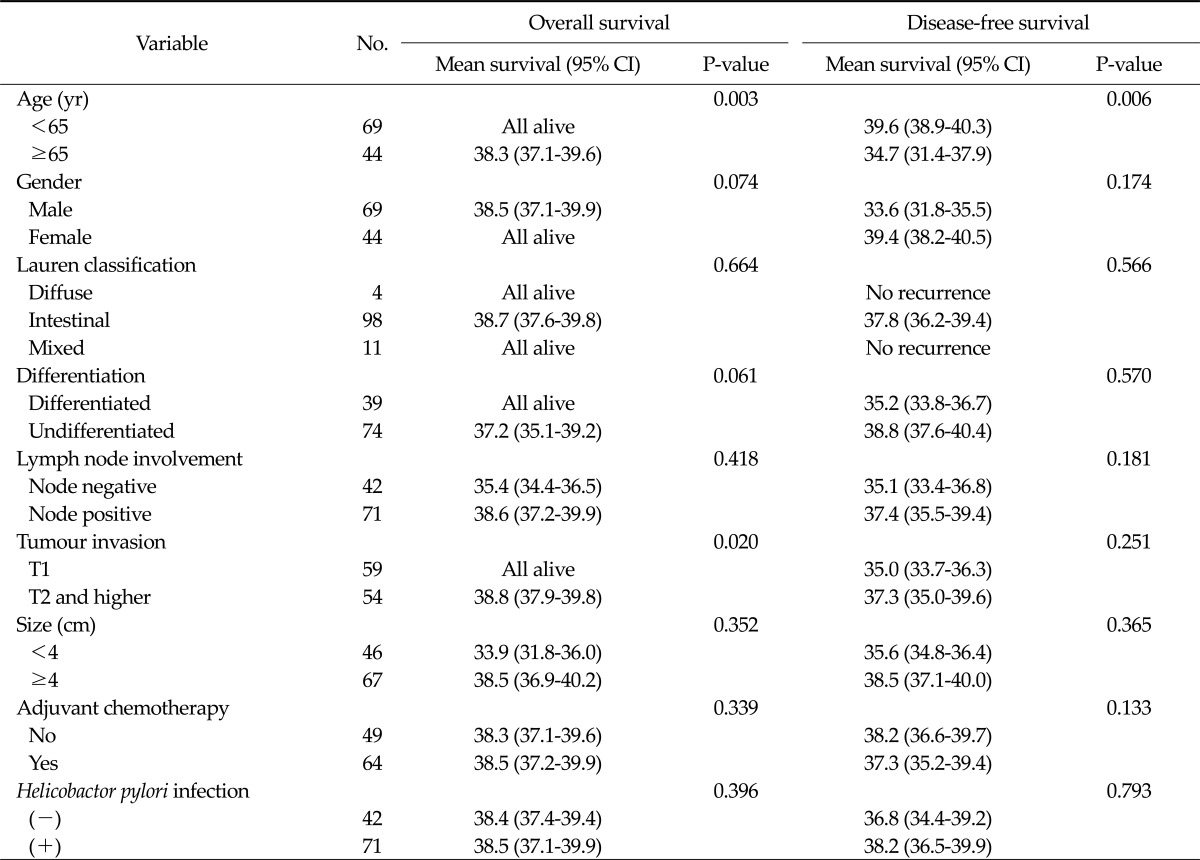

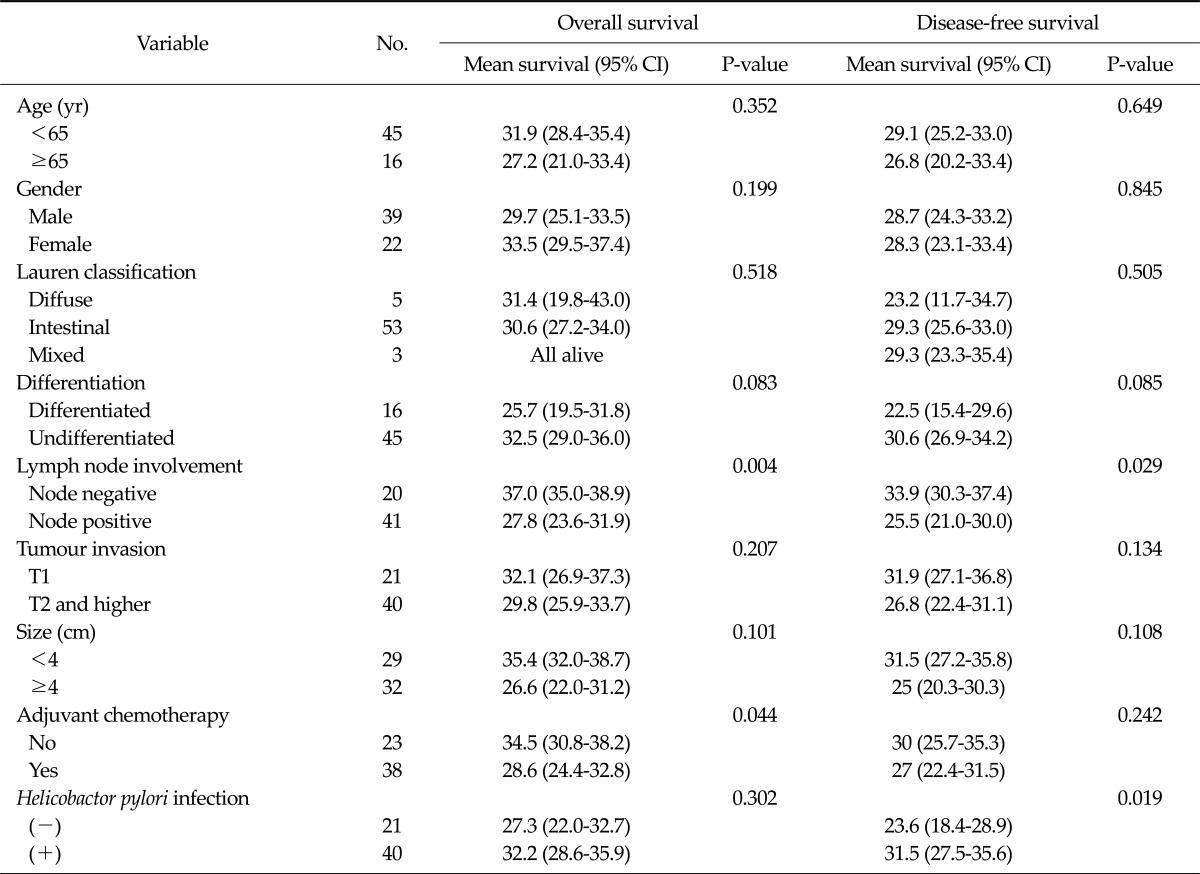

A subgroup analysis was performed by dividing the patients into two groups according to their AJCC stage (stages I or II and III or IV). In patients with stage I or II cancer, a younger age (P = 0.003) and reduced tumour invasion (P = 0.020) were significantly associated with an improved overall survival; a younger age (P = 0.006) was also associated with a higher disease-free survival rate. However, H. pylori infection status did not significantly correlate with the overall (P = 0.396) or disease-free survival (P = 0.793) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Survival analysis in patients pathologically diagnosed with stage I or II cancer (n = 113)

CI, confidence interval.

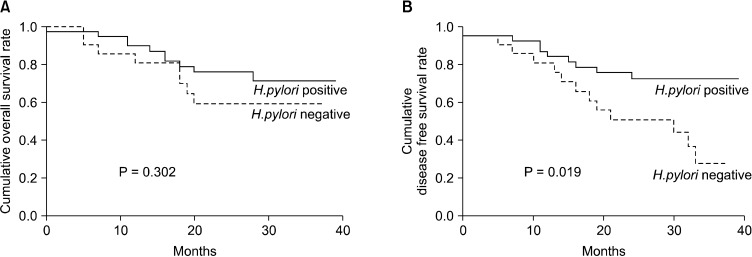

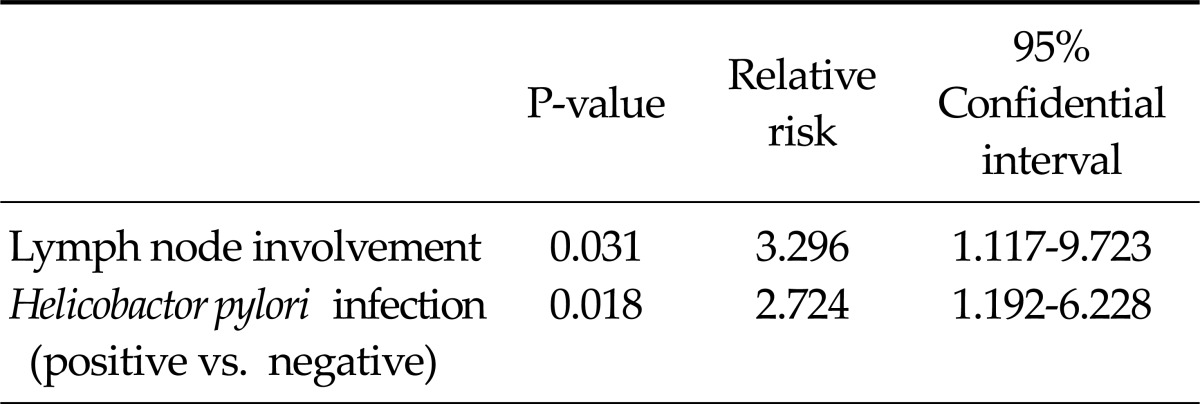

In stage III or IV cases, lymph node involvement was associated with the overall and disease-free survival. The disease-free survival of patients negative for H. pylori infections was significantly shorter than that of patients with a positive H. pylori status (P = 0.019) (Table 3). In addition, the overall survival did not differ significantly according to the H. pylori status (P = 0.302) (Fig. 3). In the multivariable analysis, a negative H. pylori status (relative risk, 2.724; 95 confidence interval, 1.192 to 6.228) was predictive of an early recurrence accompanied by lymph node involvement (Table 4).

Table 3.

Survival analysis in patients pathologically diagnosed with stage III or IV cancer (n = 61)

CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 3.

Patient survival according to Helicobactor pylori infection status in patients with advanced stage gastric cancer (stage III or IV). (A) Overall survival and (B) disease-free survival.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis for the prediction of recurrence in stage III or IV patients (n = 61)

DISCUSSION

Patients diagnosed with advanced stage gastric cancer have a poor prognosis despite resection of the primary tumour and perigastric lymph nodes. The most reliable factor for predicting the prognosis of gastric cancer patients appears to be TNM stage, which is based on the level of invasion and metastasis to local lymph nodes [12,13]. In our study, the overall and disease-free survival were significantly correlated with the TNM stage determined according to the AJCC guidelines. However, patients at the same stage can have a variable prognosis. Several independent factors have been proposed to account for this variance in patients that have undergone curative resection of gastric cancer. These factors have included the lymphatic and venous spread of tumour cells and the expression of specific proteins, such as c-erbB2 and vascular endothelial growth factor [14-17]. However, the correlation between these factors and prognosis for gastric cancer patients did not meaningful evidence. Therefore, other ideal methods for prediction of prognosis have been required. Tests for H. pylori status have been standardised for some time, and preoperative assessment is possible. The results of our study indicated that H. pylori status could be a predictive factor for early recurrence in patients at an advanced stage of gastric cancer.

To date, two prospective studies have been published that evaluate the correlation between H. pylori status and the prognosis of gastric cancer patients in Western countries (i.e., Italy and Germany) [7,8]. Compared to previous research, the critical difference in our study was that the patients were enrolled in Korea, which is a country with a high rate of H. pylori infection. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to suggest that H. pylori infection is a superior prognostic factor in a population with a high prevalence of H. pylori. Several studies have demonstrated that gastric cancer patients in Eastern societies exhibit improved survival rates relative to patients in Western populations [18,19]. These studies proposed that survival differences may be dependent on differences in surgical aggressiveness, tumour staging and tumour biology between the two regions. However, no study has described a correlation between the differences in gastric cancer survival rates and H. pylori prevalence. Based on our results, the high prevalence of H. pylori may also be a fundamental reason why gastric cancer patients in Eastern societies have showed a better prognosis. In addition, we decided the infection of H. pylori using postoperative histological evaluation combining with serologic test, in contrast to Western prospective studies. It may be more meaningful regarding suggestion the infection of H. pylori as the prognostic marker after curative resection, and contributing to the decision about the adjuvant treatment.

In contrast with a prospective study performed in Germany [8], patients with positive H. pylori status in our study showed an improved disease-free survival only in the advanced stages of the disease. Differences in surgical strategies between the two regions may have caused this result. Randomised controlled clinical trials conducted in Western countries have demonstrated that perigastric lymph node dissection followed by gastrectomy was sufficient in the treatment of all localised gastric cancers based on cancer survival and operative morbidity [20,21]. However, the surgical strategy used in our institution has followed the Japanese perspective, which recommends extended lymphadenectomy (over D1 + β lymph node dissection) for gastric cancer with invasion of tumours as small as T1 [22]. The aggressive resection of localised gastric cancers might be the reason why H. pylori status did not confer a difference in prognosis in the early stages of gastric cancer. However, further follow-up may show differences according to H. pylori status even in stages I and II.

To date, several hypotheses on the biological and immunological consequences of H. pylori infection have been suggested to explain the correlation between a positive H. pylori status and a better prognosis. First, several studies have demonstrated a significant association between H. pylori infection and microsatellite instability (MSI) [23,24]. These studies suggest that gastric cancer with MSI might result in an increased H. pylori virulence through molecular pathways. Although a separate report has suggested that gastric cancer with MSI was associated with a favourable outcome [25], further studies are required to identify how the presence of MSI explains the direct correlation between H. pylori status and prognosis. Second, an improved prognosis in gastric cancer patients that are positive for H. pylori may be the result of a local immune response to H. pylori infection. Several reports have suggested that the induction of a local B-cell response in gastric mucosa and a type 1 T-helper cell immune response following H. pylori infection may contribute to the improved prognosis of gastric cancer patients [26,27]. However, the connection between the immune response induced by H. pylori and patient prognosis requires further confirmation. In addition, one clinical research study has suggested that the poor prognosis of gastric cancer patients that are negative for H. pylori could be the result of a more aggressive form of gastric cancer [28]. The further progression of gastric cancer results in an increased destruction of the parietal cells in the stomach mucosa; the lumen of the stomach then becomes an alkaline environment, which is unfavourable for H. pylori.

In this study, we defined a positive H. pylori infection based on both serologic and histological analyses. H. pylori infection can be diagnosed in a number of different ways. Conventional serologic testing by ELISA is considered the most accurate method for determining previous H. pylori infections because the IgG antibody may persist for several months after a bacterial infection [29,30]. Even following eradication therapy, there is a delay in the decrement of serum IgG antibody, thereby allowing IgG to be used as a tool in the detection of past H. pylori infections. On the other hand, a current H. pylori infection can be confirmed based on histological findings using Giemsa staining. As previously described, the effects of H. pylori status on the prognosis of gastric cancer patients can be estimated by observing immunologic responses, such as the eradication of H. pylori infection in the aggressive tumors. Therefore, both present and past H. pylori infections could explain the strong effect of H. pylori status on the prognosis of gastric cancer patients. In addition, these detection methods are less expensive and are more practical diagnostic tools than other modalities used for the evaluation of H. pylori infection, such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for vac-A antigen or bacterial culturing.

In conclusion, H. pylori status did not show a correlation with clinicopathologic factors of gastric adenocarcinoma in Korea. However, negative H. pylori status may be a predictive factor for recurrence in patients diagnosed with advanced stage gastric adenocarcinoma. Therefore, in H. pylori endemic areas, patients diagnosed with locally advanced gastric cancer accompanied by negative H. pylori status should be considered for an aggressive treatment strategy and close follow up. In addition, the correlation observed in the early stages of gastric cancer should be confirmed in future studies with longer follow-up times.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare technology R&D project, Ministry of Health, Welfare, & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (1020410).

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Choi Y, Gwack J, Kim Y, Bae J, Jun JK, Ko KP, et al. Long term trends and the future gastric cancer mortality in Korea: 1983-2013. Cancer Res Treat. 2006;38:7–12. doi: 10.4143/crt.2006.38.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; International Agency for Research on Cancer; World Health Organization. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. Lyon: IARC; 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Yokota K, et al. The effect of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on the development of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1037–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, Chen JS, Zheng TT, Feng RE, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong O, Park YK. Clinicopathologic features and surgical treatment of gastric cancer in South Korea: The results of 2009 nationwide survey on surgically treated gastric cancer patients. J Gastric Cancer. 2011;11:69–77. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2011.11.2.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marrelli D, Pedrazzani C, Berardi A, Corso G, Neri A, Garosi L, et al. Negative Helicobacter pylori status is associated with poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:2071–2080. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meimarakis G, Winter H, Assmann I, Kopp R, Lehn N, Kist M, et al. Helicobacter pylori as a prognostic indicator after curative resection of gastric carcinoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:211–222. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70586-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu H, Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. The Helicobacter pylori restriction endonuclease-replacing gene, hrgA, and clinical outcome: comparison of East Asia and Western countries. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1551–1555. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000042263.18541.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SY, Ahn JS, Ha YJ, Doh HJ, Jang MH, Chung SI, et al. Serodiagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korean patients using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Immunoassay. 1998;19:251–270. doi: 10.1080/01971529808005485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. Gastric Cancer. (2nd english edition) 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/s101209800016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baba H, Korenaga D, Okamura T, Saito A, Sugimachi K. Prognostic factors in gastric cancer with serosal invasion. Univariate and multivariate analyses. Arch Surg. 1989;124:1061–1064. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1989.01410090071015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maruyama K, Gunven P, Okabayashi K, Sasako M, Kinoshita T. Lymph node metastases of gastric cancer: general pattern in 1931 patients. Ann Surg. 1989;210:596–602. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198911000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinto-de-Sousa J, David L, Almeida R, Leitao D, Preto JR, Seixas M, et al. c-erb B-2 expression is associated with tumor location and venous invasion and influences survival of patients with gastric carcinoma. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10:247–256. doi: 10.1177/106689690201000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Rahden BH, Stein HJ, Feith M, Becker K, Siewert JR. Lymphatic vessel invasion as a prognostic factor in patients with primary resected adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:874–879. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yonemura Y, Endo Y, Fujita H, Fushida S, Ninomiya I, Bandou E, et al. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor C expression in the development of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1823–1829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yonemura Y, Ninomiya I, Yamaguchi A, Fushida S, Kimura H, Ohoyama S, et al. Evaluation of immunoreactivity for erbB-2 protein as a marker of poor short term prognosis in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 1991;51:1034–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hundahl SA, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base Report on poor survival of U.S. gastric carcinoma patients treated with gastrectomy: fifth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer staging, proximal disease, and the "different disease" hypothesis. Cancer. 2000;88:921–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strong VE, Song KY, Park CH, Jacks LM, Gonen M, Shah M, et al. Comparison of gastric cancer survival following R0 resection in the United States and Korea using an internationally validated nomogram. Ann Surg. 2010;251:640–646. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d3d29b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonenkamp JJ, Hermans J, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ, Welvaart K, Songun I, et al. Extended lymph-node dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:908–914. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903253401202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, Bancewicz J, Craven J, Joypaul V, et al. Surgical Co-operative Group. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1522–1530. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sano T. Tailoring treatments for curable gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2007;94:263–264. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung WK, Kim JJ, Kim JG, Graham DY, Sepulveda AR. Microsatellite instability in gastric intestinal metaplasia in patients with and without gastric cancer. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:537–543. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64758-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu MS, Lee CW, Shun CT, Wang HP, Lee WJ, Sheu JC, et al. Clinicopathological significance of altered loci of replication error and microsatellite instability-associated mutations in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1494–1497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu MS, Lee CW, Sheu JC, Shun CT, Wang HP, Hong RL, et al. Alterations of BAT-26 identify a subset of gastric cancer with distinct clinicopathologic features and better postoperative prognosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bamford KB, Fan X, Crowe SE, Leary JF, Gourley WK, Luthra GK, et al. Lymphocytes in the human gastric mucosa during Helicobacter pylori have a T helper cell 1 phenotype. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:482–492. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattsson A, Lonroth H, Quiding-Jarbrink M, Svennerholm AM. Induction of B cell responses in the stomach of Helicobacter pylori-infected subjects after oral cholera vaccination. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:51–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hobsley M, Tovey FI, Holton J. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: neither friend nor foe. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2076. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cutler AF, Prasad VM. Long-term follow-up of Helicobacter pylori serology after successful eradication. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang WM, Chen CY, Jan CM, Chen LT, Perng DS, Lin SR, et al. Long-term follow-up and serological study after triple therapy of Helicobacter pylori-associated duodenal ulcer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1793–1796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]