INTRODUCTION

Most malignant primary tumors of the liver are hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) of the liver is considered as a variant of cholangiocarcinoma and is very rare. ASC consists of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma components and has a poor prognosis.1 In this study, we present a case of ASC of the liver and discuss the histopathologic findings.

CASE SUMMARY

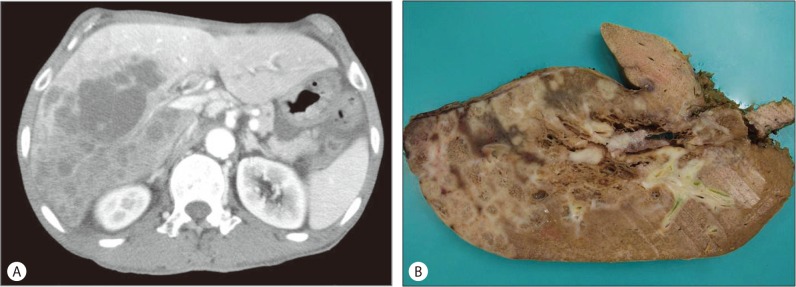

A 67-year-old man presented with a one-month history of poor oral intake and abdominal discomfort. He had a surgical history of gastric antrectomy due to a duodenal ulcer. A physical examination revealed mild distension of the abdomen, but no palpable mass. The serum level of alkaline phosphatase was 260 IU/L (normal range, 40-120 IU/L) and CA19-9 was 994.9 U/mL (normal range, 0-35 U/mL); other liver function tests were within normal limits. Serological tests for hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus showed negative. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed multiple peripheral enhancing masses in the right lobe of the liver (Fig. 1A). No abnormalities were found on systemic examinations. The patient underwent trisegmentectomy with regional lymph node dissection.

Figure 1.

(A) Contrast abdominal CT scan reveals multiple masses with thin rim-like enhancements around the periphery of the tumor, but the center of the lesion is not enhanced. (B) In the trisegmentectomy specimen, the cut surface reveals multiple whitish masses with spongiform changes.

PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS

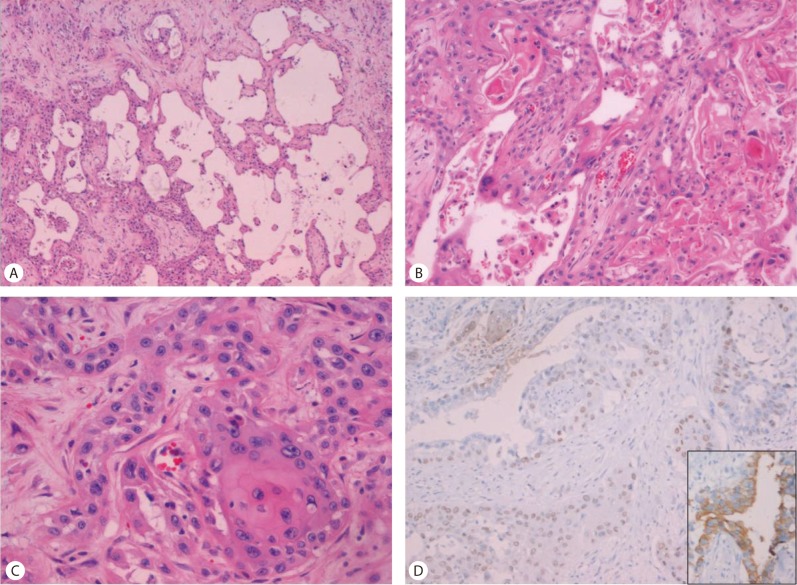

Gross examination revealed multiple whitish solid masses with spongiform appearance (Fig. 1B). Histopathologically, multiple masses had central microcystic spaces and peripheral solid areas (Fig. 2A). Microcystic spaces were variable in size and lined with polygonal cells with prominent nuclear atypia mimicking a vascular tumor. Keratin material and multinucleated giant cells were present in a few cystic spaces (Fig. 2B). The main tumor components consisted of poorly-formed glandular structures and well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, with keratin formation within the fibrous stroma. Transitional areas of squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma were also observed (Fig. 2C). No metastasis was noted in the dissected lymph nodes. Considering these findings, differential diagnosis should be ASC or a malignant vascular tumor, such as epithelioid hemangioendothelioma or angiosarcoma. Immunohistochemistry revealed that tumor cells were negative for endothelial cell markers including CD31 and CD34; therefore we could rule out a malignant vascular tumor. Keratin 7 is expressed by most glandular and transitional epithelia but not expressed in the stratified squamous epithelia, whereas p63 is expressed in most squamous cell carcinoma.2 The tumor cells comprising of glandular structures were positive for keratin 7 (Fig. 2D, inset) and 19, whereas squamous cell carcinoma showed nuclear p63 staining (Fig. 2D). On the basis of the histological and immunohistochemical findings, the final diagnosis of ASC of the liver was made.

Figure 2.

(A) The grossly spongiform area matches variable-sized cystic spaces (H&E stain, ×40). (B) Variable-sized spaces are lined with polygonal cells with nuclear atypia (H&E stain, ×200). (C) A transitional area of squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma is present (H&E stain, ×400). (D) Immunohistochemistry for p63 reveals nuclear positive staining for squamous cell carcinoma, whereas adenocarcinoma cell staining is negative. Inset: Keratin 7 positivity in adenocarcinoma cells (×200).

DISCUSSION

ASC consists of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma components in the same tumor and has been referred to as adenoacanthoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma.1,3 ASC sometimes develops in the stomach, pancreas, gallbladder and thyroid, but rarely in the liver.4 Since 1971, when ASC of the liver was first reported as "mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the liver" by Pianzola and Durt,3 about 56 cases have been published. However, the histogenesis of ASC still remains unclear. Various theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of ASC of the liver. Continuous irritations of the bile duct and various congenital cysts of the biliary tract by chronic inflammation or infection can induce metaplastic changes in the biliary epithelium and have been thought to lead to neoplasia.5 Barr and Hancock6 suggested that ASCs arise from squamous metaplasia of adenocarcinoma cells. Preoperative diagnosis is difficult because ASCs are very rare. Most ASCs are diagnosed at the time of autopsy or after an operation and only a few ASCs have been diagnosed by needle biopsy.7

The key histologic features of ASC include an infiltrating neoplasm with solid and glandular areas, while squamous differentiation is evident by individual cell keratinization, intercellular bridges, keratin pearl formation and/or dyskeratosis, and glandular differentiation by various-sized gland formations and intracellular and intraluminal mucin.1 All these features were observed in the present case, which also exhibited some unusual features. First, the tumor grossly showed multiple masses. Malignancy presenting as multiple masses of the liver can be metastasis, malignant vascular tumor, or primary hepatic malignancy. We excluded malignant vascular tumor due to the lack of CD31 or CD34 expressing malignant endothelial cells, which are necessary for the diagnosis of malignant vascular tumor of the liver. No other abnormalities suggestive of primary malignancy were found on systemic examinations. Second, multiple foci were present that showed microcystic change with spongiform appearance. The mechanism underlying the development of microcystic change in this present ASC case remains unclear. Histologically, most of the cysts were lined with polygonal cells with prominent nuclear atypia and a few cystic spaces contained keratin material, suggestive of cystic degeneration of squamous cell carcinoma areas. Thus, we postulated that the present ASC case predominantly consisted of squamous cell carcinoma components, and that the cystic changes in the squamous cell carcinoma components resulted in the microcystic change.

ASC usually has a poorer prognosis than common adenocarcinoma since ASC tends to present more aggressive clinicopathologic features, such as lymphatic permeation, vascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, and intrahepatic metastasis.7 According to Takahashi et al,7 squamous cell carcinoma components have DNA aneuploidy patterns and high proliferative activity, so that a squamous cell carcinoma component shows more malignant biological behavior. Suzuki et al8 described the mean survival periods for patients with (n=5) and without (n=23) lymph node dissection were 29.6 and 6.2 months, respectively. All ASC patients surgically resected died of the disease within 4-8 months after surgery and the survival curve of patients with ASC was also significantly worse than that of patients with common cholangiocarcinoma.9 The patient died of liver failure and multiple organ dysfunction two days after the operation.

Abbreviations

- ASC

adenosquamous carcinoma

- CT

computed tomography

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Nakanuma Y, Curado MP, Franceschi S, Gore G, Paradis V, Sripa B, et al. The International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcioma. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2010. pp. 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camilo R, Capelozzi VL, Siqueira SA, Del Carlo Bernardi F. Expression of p63, keratin 5/6, keratin 7, and surfactant-A in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:542–546. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pianzola LE, Drut R. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the liver. Am J Clin Pathol. 1971;56:758–761. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/56.6.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gu MJ, Choi JH, Park WK, Chang JC, Kim HJ. Primary adenosquamous carcinoma of the liver: a case report. Korean J Hepatol. 2005;11:86–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubo S, Sakai T, Nagata E, Ikawa S, Hirohashi K, Kinoshita H, et al. Resection of adenosquamous carcinoma of the liver: A case report (in Japanese) Gastroenterol Surg. 1983;6:1775–1779. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr RJ, Hancock DE. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the liver. Gastroenterology. 1975;69:1326–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi H, Hayakawa H, Tanaka M, Okamura K, Kosaka A, Mizumoto R, et al. Primary adenosquamous carcinoma of liver resected by right trisegmentectomy: report of a case and review of the literature. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:843–847. doi: 10.1007/BF02936966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki E, Hirai R, Ota T, Shimizu N. Primary adenosquamous carcinoma of the liver: case report. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:769–773. doi: 10.1007/s005340200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maeda T, Takenaka K, Taguchi K, Kajiyama K, Shirabe K, Shimada M, et al. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the liver: clinicopathologic characteristics and cytokeratin profile. Cancer. 1997;80:364–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]