Abstract

Objectives

To develop and validate a simple clinical prediction rule, based on variables easily measurable at admission, to identify patients at high risk of developing delirium during their hospital stay on an internal medicine ward.

Design

Prospective study of two cohorts of patients admitted between 1 May and 30 June 2008 (derivation cohort), and between 1 May and 30 June 2009 (validation cohort).

Setting

A tertiary hospital in Donostia-Gipuzkoa (Spain).

Participants

In total 397 patients participated in the study. The mean age and incidence of delirium were 75.9 years and 13%, respectively, in the derivation cohort, and 75.8 years and 25% in the validation cohort.

Main outcome measures

The predictive variables analysed and finally included in the rule were: being aged 85 years old or older, being dependent in five or more activities of daily living, and taking two or more psychotropic drugs (antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, anticonvulsant and/or antidementia drugs). The variable of interest was delirium as defined by the short Confusion Assessment Method, which assesses four characteristics: acute onset and fluctuating course, inattention, disorganised thinking and altered level of consciousness.

Results

We developed a rule in which the individual risk of delirium is obtained by adding one point for each criterion met (age≥85, high level of dependence, and being on psychotropic medication). The result is considered positive if the score is ≥1. The rule accuracy was: sensitivity=93.4% (95% CI 85.5% to 97.2%), specificity=60.6% (95% CI 54.1% to 66.8%), positive predictive value=44.4% (95% CI 36.9% to 52.1%) and negative predictive value=96.5% (95% CI: 92% to 98.5%). The area under the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve was 0.85 for the validation cohort.

Conclusions

The presence or absence of any of the three predictive factors (age≥85, high level of dependence and psychotropic medication) allowed us to classify patients on internal medicine wards according to the risk of developing delirium. The simplicity of the variables in our clinical prediction rule means that the data collection required is feasible in busy medicine units.

Keywords: Delirium, clinical prediction rule, elderly

ARTICLE SUMMARY.

Article focus

The aim of this research was to develop and validate a simple clinical prediction rule to identify patients at high risk of developing delirium during their hospital stay on an internal medicine ward.

Key messages

This is a simple clinical prediction rule based on easily measurable variables at admission with a very high sensitivity (0.934).

This rule may facilitate early identification of high risk patients and target early initiation of preventive measures.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A prospective study design was used for the derivation and for the validation rule.

The simplicity of the variables included in our rule makes data collection a feasible task for busy healthcare units.

The diagnoses of delirium were not confirmed by a psychiatrist.

Introduction

Delirium, also referred to as acute confusional state, is an acute disturbance of attention and cognition with a fluctuating course that often appears in hospitalised patients. Between 10% and 30% of patients admitted to general hospitals develop delirium,1–3 with a prevalence of up to 60% among frail elderly patients.4 It is a serious complication that increases mortality5 and reduces the functional status of patients,6 as well as increasing the length of hospital stays7 8 and rates of readmission.9 While the pathophysiology of delirium remains poorly understood, multiple risk factors have been identified.10 These can be classified into two groups: factors that increase baseline vulnerability (presence of dementia, cerebrovascular accident, Parkinson's disease, old age and sensory impairment, among others);11 and those that may be a trigger (such as polypharmacy, infection and dehydration).12–14

Various interventions to improve modifiable variables have been found effective in preventing the occurrence of delirium.15–18 Therefore, the identification of patients at high risk of developing delirium is particularly important.19

Clinical prediction rules are useful tools for classifying patients at different levels of risk.20 Other authors proposed a rule to predict the risk of developing delirium21 for use in patients admitted due to clinical worsening of their condition, but its use has not become widespread in our setting since it requires variables that are difficult to measure on admission (Mini-Mental State Examination score, and visual acuity, among others).

The objective of this study was to derive and validate a simple clinical prediction rule, based on variables that are easily measurable and are often routinely taken on admission, to identify patients at high risk of developing delirium during their hospital stay on an internal medicine ward.

The identification of these patients will allow us to introduce the necessary preventative measures.

Methods

Design

To develop the clinical prediction rule we assessed a prospective cohort of consecutive patients admitted in four internal medicine wards. Subsequently, we assessed a different prospective cohort of consecutive patients to validate the rule.

Patients

The derivation cohort was 397 consecutive patients aged 18 years or over, of both sexes, who were admitted to any of four internal medicine wards at Donostia Hospital between 1 May and 30 June 2008, and we used no other exclusion criteria. The following year, between 1 May and 30 June 2009, we recruited the validation cohort on the same basis: 302 consecutive patients aged 18 or over, of both sexes, who were admitted to any of the same four internal medicine wards at the hospital. The consent was obtained from the study participants and all patients gave their consent to participate in the study.

Assessment of delirium

We defined delirium using the short version of the Confusion Assessment Method,22 a short form for assessing confusion. This diagnostic algorithm assesses four characteristics: (1) acute onset and fluctuating course, (2) inattention, (3) disorganised thinking and (4) altered level of consciousness. The diagnosis of delirium required the presence of (1) and (2), and either (3) or (4) (or both). This assessment was performed by two independent researchers, when it was considered that patients were ready for discharge, after analysis of any relevant data in their medical record and nursing report. Disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third researcher. All these evaluators were blinded to the potential predictive variables selected for the study.

Potential predictors

The potential predictive variables for delirium were selected after a systematic review of the literature.10–14 23–25 We sought to identify variables that were easy to measure and are often routinely recorded on admission to these wards.

The following variables were selected and measured on admission: age (years), sex, systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), heart rate (beats/min), respiratory rate (breaths/min), axillary temperature (°C), oxygen therapy (no: not used; and yes: oxygen with nasal cannula, mask and/or oxygen at home), fluid therapy, presence of urinary catheter, level of consciousness (normal: alert; or altered: drowsiness, unresponsiveness to voice, unresponsiveness to pain and/or generally unresponsive), diagnosis of infection at admission (respiratory, urinary or other types of infections; or no infection: any other cause of admission), admission in the previous year, admission in the previous month, hearing impairment (use of a hearing aid, or deafness reported by the patient or caregiver), vision impairment (regular use of glasses or reduction in visual acuity reported by the patient or caregiver), and dementia (in a medical report or reported by the caregiver). In addition, blood tests were taken on admission to measure the following: haematocrit (%), levels of urea (mg/dl), creatine (mg/dl), sodium (mEq/l), potassium (mEq/l) and glucose (mg/dl), as well as white blood cell (10e3/μl) and neutrophil (10e3/μl) counts. Finally, certain characteristics of patients prior to admission were also assessed: level of dependence for activities of daily living (ADL) (personal hygiene and grooming, dressing and undressing, getting onto or off toilet, ambulation, bowel and bladder control and self-feeding) as dichotomous variables (dependent; independent); presence of pressure ulcers and excess alcohol intake (>60 g/ethanol/day), as well as use of certain types of medication: benzodiazepines, antidepressants, antidementia drugs, antipsychotics, anti-Parkinson's drugs or anticonvulsants.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was carried out, based on the calculation of means and SDs for continuous variables, and absolute or relative frequencies as percentages for categorical variables. Subsequently, some continuous variables were dichotomised using the median value.

Sample size

Assuming a prevalence of delirium at admission of 10%, it was calculated that we needed 10 patients with delirium for each variable included in the model, with the intention that the model should be as parsimonious as possible.

Comparison between derivation and validation cohorts

We compared the characteristics of patients in the derivation cohort with those in the validation cohort using the Student t test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for ordinal and dichotomous variables.

Derivation of the prediction rule

The characteristics of patients who developed delirium were compared with those of patients who did not, again using the Student t test or the χ2 test as appropriate. A p value <0.25 was taken to indicate potentially predictive variables and those meeting these criteria were included in the multivariate model. Then, using a stepwise logistic regression model we selected the terms (predictive variables) to be included in the final model. The criteria for entry in the model and for removal were p≤0.05 and p≥0.10, respectively. The Hosmer Lemeshow test was performed to assess the goodness of fit of this model.

We note that we also explored selecting variables for an alternative prediction rule by recursive partitioning. However, as the performance of this rule was poorer than that of the rule obtained by logistic regression, we decided to report exclusively the data concerning the rule derived using the latter method.

Validation cohort and model performance

The clinical prediction rule was applied to the validation cohort. We report the incidence of delirium as a function of score on the rule and the ORs using the lowest risk category as the reference. The performance of the rule in the two cohorts was explored using receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

To assess the predictive accuracy of the rule, we constructed a 2×2 table for calculation of the following: sensitivity, specificity and positive (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV). The 95% CIs of these indicators were also calculated assuming a binomial distribution.

We used SPSS V.19.0 and MedCalc for all the analyses.

Results

In the validation cohort, 13% of patients (52 of 397) developed delirium, and in the derivation cohort the incidence was 25.2% (76 of 302). Table 1 summarises baseline characteristics of the derivation and validation cohorts. Patients included in our study were elderly (76.4±13.3 years old) and slightly more than half were women (52%, 362 of 699). The derivation and validation cohorts were similar in some respects, namely, age, sex, mean length of stay and types of medication. On the contrary, patients in the validation cohort were significantly more dependant in certain ADL: personal hygiene and grooming, dressing and undressing and getting onto or off toilet.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients in the derivation and validation cohorts

| Characteristics | Derivation cohort (n=397) | Validation cohort (n=302) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 75.9 (13.3) | 76.8 (13.3) | NS |

| Mean length of stay (SD) | 8.4 (5.8) | 8 (6.1) | NS |

| Women (%) | 197 (49.6) | 165 (54.3) | NS |

| Medication (%) | |||

| Benzodiazepines | 162 (40.8) | 134 (44.4) | NS |

| Antidepressants | 75 (18.9) | 74 (24.5) | NS |

| Antidementia drugs | 20 (5) | 11 (3.6) | NS |

| Antipsychotics | 24 (6) | 21 (7) | NS |

| Anti-Parkinson's agents | 13 (3.3) | 6 (2) | NS |

| Anticonvulsants | 20 (5) | 16 (5.3) | NS |

| Dependence in activities of daily living (%) | |||

| Personal hygiene and grooming | 155 (39) | 171 (56.6) | <0.05 |

| Dressing and undressing | 155 (39) | 174 (57.6) | <0.05 |

| Getting onto or off toilet | 146 (36.8) | 161 (53.3) | <0.05 |

| Ambulation | 163 (41.1) | 166 (55) | <0.05 |

| Bowel and bladder control | 139 (35) | 122 (40.4) | NS |

| Self-feeding | 109 (27.5) | 102 (33.8) | NS |

NS, not significant.

Tables 2–6 report the results of the univariate analysis in which the risk factors were compared between patients who developed delirium and those who did not within the derivation cohort. Those who developed delirium were significantly older and had slightly higher respiratory rates, but there were no significant differences in blood test results.

Table 2.

Derivation cohort: univariate analysis of patient clinical variables considered potential risk factors for delirium at admission

| Variables | Delirium | No delirium | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 83.83 (9.8) | 74.75 (13.4) | 0.000 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | 127.5 (27.1) | 132.3 (26.5) | 0.22 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | 27.92 (9.6) | 24.42 (6.6) | 0.001 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 86.6 (23.8) | 84.06 (22.5) | NS |

| Body temperature (°C) | 36.7 (0.7) | 36.7 (0.8) | NS |

| Women (%) | 26 (50) | 171 (49.6) | NS |

| Excess alcohol intake (%) | 2 (3.8) | 19 (5.5) | NS |

| Mean length of stay in hospital (days) | 9.3 (6.6) | 8.3 (5.6) | NS |

| Admission in previous year (%) | 26 (50) | 152 (44.1) | NS |

| Admission in previous month (%) | 8 (15.1) | 45 (84.9) | NS |

Mean (SD).

NS, not significant.

Table 3.

Derivation cohort: univariate analysis of patient blood test results at admission

| Variables | Delirium | No delirium | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haematocrit (%) | 39.31 (7.6) | 37.42 (6.5) | 0.058 |

| Urea (mg/dl) | 62.3 (31.6) | 60.3 (40.7) | NS |

| Creatine (mg/dl) | 1.14 (0.5) | 1.25 (0.9) | NS |

| Sodium (mEq/l) | 138.5 (5.6) | 173.9 (5.5) | NS |

| Potassium (mEq/l) | 5.2 (6.9) | 4.8 (0.7) | NS |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 140.1 (66.3) | 140.8 (78.8) | NS |

| White blood cells (10e3/μl) | 12.1 (12.2) | 10.1 (4.7) | NS |

| Neutrophils (10e3/μl) | 9.8 (8.5) | 10.8 (14.8) | NS |

Mean (SD).

NS, not significant.

Table 4.

Derivation cohort: univariate analysis of patient medication prior to admission

| Variables | Delirium | No delirium | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressants | 16 (30.8) | 59 (17.1) | 0.023 |

| Antidementia drugs | 5 (9.6) | 15 (4.3) | 0.16 |

| Antipsychotics | 8 (15.4) | 16 (4.6) | 0.007 |

| Anticonvulsants | 5 (9.6) | 15 (4.3) | 0.16 |

| Benzodiazepines | 23 (44.2) | 139 (40.3) | NS |

NS, not significant.

Table 5.

Derivation cohort: variables characterising patient status on admission

| Variables | Delirium | No delirium | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary catheter | 13 (25) | 37 (10.7) | NS |

| Fluid therapy | 29 (55.8) | 124 (35.9) | 0.009 |

| Vision impairment | 36 (69.2) | 192 (55.7) | 0.072 |

| Hearing impairment | 9 (17.3) | 87 (25.2) | NS |

| Oxygen therapy | 32 (61.5) | 202 (58.6) | NS |

| Pressure ulcers | 3 (5.8) | 25 (7.3) | NS |

| Level of consciousness | 5 (21.7) | 18 (78.3) | 0.20 |

| Dementia | 18 (34.6) | 49 (14.2) | 0.001 |

| Infection | 28 (53.8) | 141(40.8) | 0.097 |

NS, not significant.

Table 6.

Derivation cohort: univariate analysis of patient activities of daily living

| Variables | Delirium | No delirium | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impaired personal hygiene and grooming | 39 (75) | 116 (33.6) | 0.0001 |

| Impaired dressing and undressing | 38 (73.1) | 117 (33.9) | 0.0001 |

| Impaired getting onto or off toilet | 36 (69.2) | 110 (31.9) | 0.001 |

| Impaired ambulation | 38 (73.1) | 125 (36.2) | 0.001 |

| Impaired bowel and bladder control | 36 (69.2) | 103 (29.9) | 0.001 |

| Impaired self-feeding | 31 (59.6) | 78 (22.6) | 0.000 |

| Dependence in ≥5 activities | 36 (69.2) | 87 (25.2) | 0.0001 |

Age was dichotomised using a cut-off of 85 years, a value that was found to have a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 56% for delirium by the ROC curve analysis. We found that the risk of delirium associated with the types of medication considered was similar for all except for antipsychotic drugs, in the case of which the risk was twice as high. Accordingly, the medication data was coded according to the number of different drugs patients were taking at admission with each antidepressant, antidementia or anticonvulsant drug contributing equally, while antipsychotic drugs were weighted by a factor of two. The ADL data were also dichotomised with a cut-off of reported impairments in five activities.

The scores for the clinical prediction rule were assigned on the basis of regression coefficients obtained in the logistic regression model (table 7). One point was given to patients older than 85 years, to those who had two or more points in the variable drugs, and to those with impairments in five or more of the ADL considered. Therefore, the total score for the rule ranged between 0 and 3.

Table 7.

Variables included in the logistic regression model

| Variables | B | SE | Wald | Degrees of freedom | Significance | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 1.381 | 0.349 | 15.664 | 1 | 0.000 | 3.978 |

| DADLs† | 1.397 | 0.350 | 15.924 | 1 | 0.000 | 4.042 |

| Drugs‡ | 1.515 | 0.443 | 11.715 | 1 | 0.001 | 4.547 |

| Constant | −3.234 | 0.295 | 120.122 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.039 |

Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit test p=0.873.

*Age: >85 years old.

†DADLs: dependence in five or more activities of daily livings.

‡Drugs: total of two or more points for drugs taken on admission where antidepressants, antidementia drugs and anticonvulsants score one point each, and antipsychotics score two points.

The patients with delirium of the two cohorts scored similarly: 17% and 7% scored 0, 48% and 30% scored ≤1 and 85% and 85% scored ≤2 in the derivation and validation cohort, respectively.

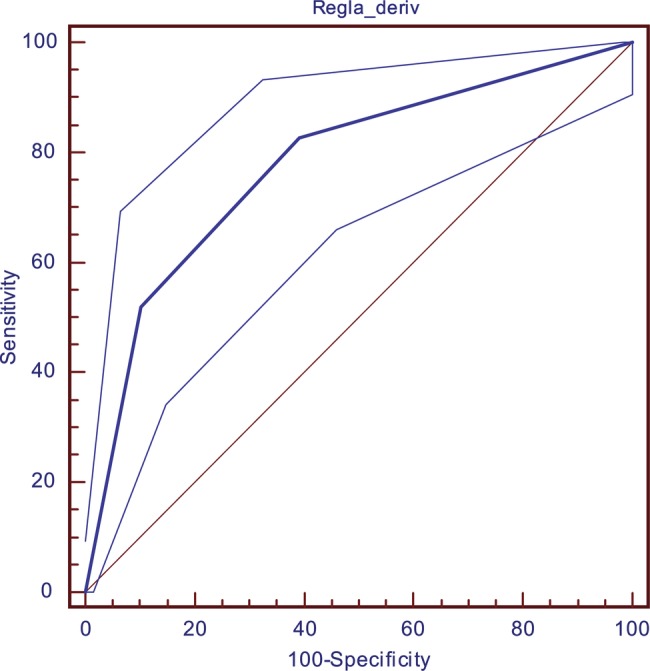

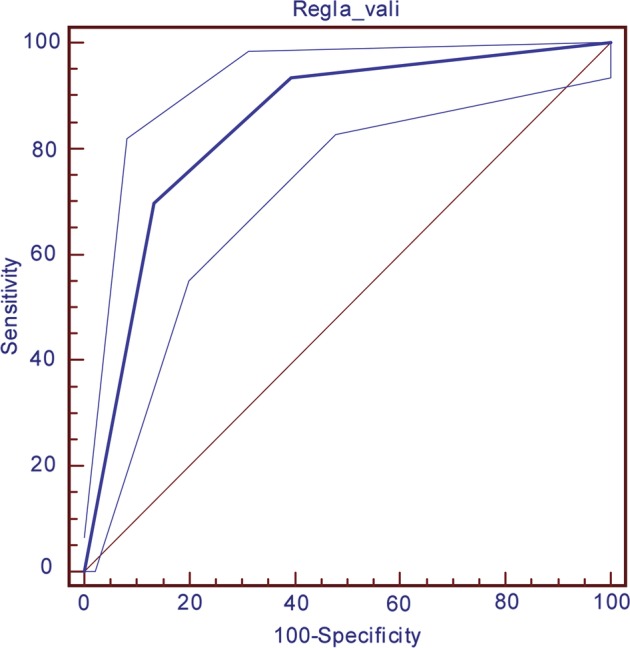

Table 8 and figures 1 and 2 describe the performance of the rule in the derivation and validation cohorts. In both cohorts, we observed higher rates of delirium associated with higher scores on the rule, the model having a good predictive power for the validation cohort (area under the ROC curve, AUC=0.85). In contrast with what would be expected, the values obtained in the validation cohort are better than those obtained in the derivation cohort, and this is probably related to the higher incidence of delirium in the validation group.

Table 8.

Logistic regression model

| Group | Points on the prediction rule | Incidence of delirium (%) | OR | AUC (95% IC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derivation cohort (n=397) | 0.77 (0.73 to 0.82) | |||

| 0 | 9/219 (4) | Reference | ||

| 1 | 16/116 (14) | 3.7 (1.5 to 8.7) | ||

| ≥2 | 27/62 (43) | 18 (7.8 to 41.5) | ||

| Validation cohort (n=302) | 0.85 (0.8 to 0.88) | |||

| 0 | 5/142 (3.5) | Reference | ||

| 1 | 18/77 (23) | 8.3 (2.9 to 23.6) | ||

| ≥2 | 53/83 (64) | 48.4 (17.8 to 131.4) |

AUC, area under the ROC curve; ROC, receiver operator characteristic.

Figure 1.

Receiver operator characteristic curve for the derivation cohort.

Figure 2.

Receiver operator characteristic curve for the validation cohort.

In particular, table 9 lists the sensitivity (Se) and specificity (Sp), as well as the PPVs and NPVs obtained when the rule was dichotomised as negative (a score of 0) or positive (as score of ≥1). For the validation cohort, the Se, Sp, NPV and PPV were 93.4%, 60.6%, 96% and 44%, respectively.

Table 9.

A 2×2 table for the validation cohort

| Cut-off point | Delirium | No delirium | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (negative) | 5 | 137 | 142 |

| ≥1 (positive) | 71 | 89 | 160 |

| 76 | 226 | 302 |

Sensitivity=93.4%, 95% CI 85.5% to 97.2%.

Specificity=60.6%, 95% CI 54.1% to 66.8%.

Positive predictive value =44.4%, 95% CI 36.9% to 52.1%.

Negative predictive value=96.5%, 95% CI 92% to 98.5%.

Discussion

In this prospective study, we identified three independent predictive factors for delirium: being 85 years old or older, being dependent in five or more ADL (of the six considered), and taking psychotropic drugs (antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, anticonvulsants and/or antidementia drugs). With these factors we developed a clinical prediction rule in which an individual risk score for delirium is obtained by adding one point for each of the factors present. Applying this rule, patients are classified as positive if they have a total score of 1 or more.

In the derivation cohort, 13% of patients developed delirium, while the incidence was somewhat higher, 25%, in the validation cohort. Patients were elderly (mean ages in the derivation and validation cohorts were 75.9±13.3 years and 76.8± 13.3 years, respectively), and there were slightly more women (52%). The mean length of hospital stay was 8±5.8 days and overall mortality was 5%. There is a significant difference in the ADL variables being those from the validation cohort more dependent than the derivation cohort. All the aforementioned variables explain the almost twofold discrepancy in the incidence of delirium between the two cohorts.

There are multiple factors for the development of delirium, the predisposing and triggering factors being well defined. The predisposing factors are mostly related to degenerative brain disease (dementia, arteriosclerosis, Parkinson's disease and depression).10 11 On the contrary, there is a diverse range of triggering factors, in particular, medication, the presence of infection, surgery, metabolic disorders and water–electrolyte imbalances, among others.13 14 23–25

In the present study, we have only explored variables that are readily available on admission, in order to use the predictive rule at that stage and be able to introduce preventative measures immediately in high-risk patients. These would include trying to avoid triggering factors for the development of delirium (such as changes of room/ward, unnecessary catheterisation, inadequate oral hydration and polypharmacy).

Interestingly, the factors found to be good predictors for the development of delirium in our study (age≥85, high level of dependence and being on psychotropic medication), to some extent, indirectly reflect the severity of the organic brain damage in patients with delirium.

Another predictive rule for delirium in this type of patients has been published21 but showed a significantly lower performance than which we obtained (AUC=0.66 (0.55 to 077) vs AUC=0.85 (0.80 to 0.90) with our rule). Further, in our opinion, it is also more difficult to apply than the rule we propose. The simplicity of the variables included in our rule makes data collection a feasible task for busy healthcare units.

Between 10% and 60% of patients admitted to hospital develop delirium, depending on the type of patient, the incidence in frail elderly patients being at the top of this range. In our study, it was 13% and 25% in the derivation and validations cohorts, respectively. Delirium is well known to be difficult to diagnose and a wide range of instruments have been developed to help detect the condition.26 27 We used the Confusion Assessment Method22 that has a sensitivity of 96% (95% CI 80% to 100%) and a specificity of 93% (95% CI 84% to 100%). In our study, the doctors in charge of the diagnosis of delirium were specialists in internal medicine, with considerable training and experience in the management of this type of patients, any differences being resolved by consensus with a third specialist. We note, however, that the diagnoses of delirium were not confirmed by a psychiatrist. This may partially explain the low incidence of delirium in our patients, that is, it may be that only the most clinically striking cases, those which required pharmacological treatment, were recognised.

The association between delirium and an increase of morbidity and mortality5 6 9 is well known, as are the effectiveness of preventive measures to avoid the development of the disease.15–18 The use of the proposed predictive rule would allow us to classify around half of our inpatients (53%) as high risk. Taking preventative measures in this high-risk group, up to 93.4% of those who developed delirium in our study would have been covered by the measures and might not have then developed the condition.

It would be interesting for the clinical predictive rule we propose to be validated in other cohorts of frail elderly patients with worsening of multiple medical conditions to check its external validity.

Conclusion

The presence or absence of any of the three predictive factors (age ≥85, high level of dependence, and psychotropic medication) allowed us to classify patients on internal medicine wards according to the risk of developing delirium. The simplicity of the variables in our clinical prediction rule means that the data collection required is feasible in busy medicine units.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the medical and nursing staff of the Department of Internal Medicine at Donostia University Hospital for their contribution to the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: JM, AB, JIE and IU participated in the design of the study. JM, AB, IB, XG, CA and NL collected all data. JIE and IU carried out the statistical analysis. JM, IU and JIE drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final version to be published. IU and JM are the guarantors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The design was evaluated and then approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Gipuzkoa Health region.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Cole MG, Ciampi A, Belzile E, et al. Persistent delirium in older hospital patients: a systematic review of frequency and prognosis. Age Ageing 2009;38:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trzepacz PT. Delirium. Advances in diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment . Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996;19:429–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leentjens AF, van der Mast RC. Delirium in elderly people: an update. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2005;18:325–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, et al. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2010;304:443–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Delirium predicts 12-month mortality. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:457–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moller JT, Cluitmans P, Rasmussen LS, et al. Long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly ISPOCD1 study. ISPOCD investigators. International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction. Lancet 1998;351:857–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCusker J, Cole MG, Dendukuri N, et al. Does delirium increase hospital stay? J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1539–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens LE, de Moore GM, Simpson JM. Delirium in hospital: does it increase length of stay? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1998;32:805–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inouye SK, Rushing JT, Foreman MD, et al. Does delirium contribute to poor hospital outcomes? A three-site epidemiologic study. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:234–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inouye SK. Delirium in hospitalized older patients: recognition and risk factors. J Geriat Psychiatry Neur 1998;11:118–25; discussion 157–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1723–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inouye SK, Charpentier PA. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons. Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA 1996;275:852–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laurila JV, Laakkonen ML, Tilvis RS, et al. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in a frail geriatric population. J Psychosom Res 2008;65:249–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Rompaey B, Schuurmans MJ, Shortridge-Baggett LM, et al. Risk factors for intensive care delirium: a systematic review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2008;24:98–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inouye S, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med 1999;340:669–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milisen K, Lemiengre J, Braes T, et al. Multicomponent intervention strategies for managing delirium in hospitalized older people: systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2005;52:79–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vidan MT, Sanchez E, Alonso M, et al. An intervention integrated into daily clinical practice reduces the incidence of delirium during hospitalization in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:2029–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siddiqi N, Holt R, Britton AM, et al. Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (2): CD005563 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005563.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, et al. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:27–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laupacis A, Sekar N, Stiell IG. Clinical prediction rules. A review and suggested modifications of methodological standards. JAMA 1997;277:488–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inouye SK, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, et al. A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:474–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 1990;113:941–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, et al. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:204–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Van Ness PH, et al. Characteristics associated with delirium in older patients in a medical intensive care unit. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1629–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Environmental risk factors for delirium in hospitalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:1327–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camilla L, Wong MD, Jayna H-L, et al. Does this patient have delirium? Value of bedside instruments. JAMA 2010;304:779–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moraga AV, Rodriguez-Pascual C. Acurate diagnosis of delirium in elderly patients. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2007;20:262–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.