Abstract

Objectives

To assess the role of serum amylase and lipase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Secondary aims were to perform a cost analysis of these enzyme assays in patients admitted to the surgical admissions unit.

Design

Cohort study.

Setting

Secondary care.

Participants

Patients admitted with pancreatitis to the acute surgical admissions unit from January to December 2010 were included in the study.

Methods

Data collated included demographics, laboratory results and aetiology. The cost of measuring a single enzyme assay was £0.69 and both assays were £0.99.

Results

Of the 151 patients included, 117 patients had acute pancreatitis with gallstones (n=51) as the most common cause. The majority of patients with acute pancreatitis had raised levels of both amylase and lipase. Raised lipase levels only were observed in additional 12% and 23% of patients with gallstone-induced and alcohol-induced pancreatitis, respectively. Overall, raised lipase levels were seen in between 95% and 100% of patients depending on aetiology. Sensitivity and specificity of lipase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis was 96.6% and 99.4%, respectively. In contrast, the sensitivity and specificity of amylase in diagnosing acute pancreatitis were 78.6% and 99.1%, respectively. Single lipase assay in all patients presenting with abdominal pain to the surgical admission unit would result in a potential saving of £893.70/year.

Conclusions

Determining serum lipase level alone is sufficient to diagnose acute pancreatitis and substantial savings can be made if measured alone.

Keywords: Pancreatitis , Pancreas, Lipase, Amylase

Article summary.

Article focus

Current guidelines suggest that lipase measurement is the most sensitive marker for diagnosing pancreatitis. Hence, do we still need to measure amylase levels?

What is the effect on cost by measuring one enzyme level only?

Key messages

Determining serum lipase level alone is sufficient to diagnose acute pancreatitis.

Substantial savings can be made if lipase were measured alone.

Strengths and limitations of this study

- This manuscript focuses on a few important issues:

- Diagnosis: lipase is more sensitive in diagnosing acute pancreatitis, irrespective of aetiology.

- Cost: there is no need to measure amylase, and all centres should measure lipase only.

Single-centre, retrospective study.

Introduction

The incidence of acute pancreatitis in the UK ranges from 150 to 420 cases per million population and is currently rising.1 In 80% of patients, acute pancreatitis is mild and resolves without serious morbidity, but in up to 20%, acute pancreatitis is complicated by substantial morbidity and mortality.2 Gallstone migration and alcohol abuse are the most common underlying aetiology, with gallstones being more frequently seen in women.3

Traditionally, serum amylase was used to establish the diagnosis of pancreatitis, irrespective of aetiology. This test is particularly useful in patients presenting with acute abdominal pain to the emergency department or the acute surgical admissions unit to confirm the diagnosis of pancreatitis. Nevertheless, few studies have suggested that serum lipase is a more sensitive biomarker of acute pancreatitis compared to serum amylase.4 5 The current British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines (2005) for the management of acute pancreatitis has also suggested a preference towards the measurement of lipase levels for the diagnosis of pancreatitis.6

At present, due to the availability of both serum amylase and lipase, these tests are frequently requested concurrently in patients presenting with acute abdominal pain. The purpose of both these tests is to confirm the diagnosis of pancreatitis, irrespective of aetiology, although the levels of these enzymes have no correlation with the severity of the disease. The aim of the current study was to assess the clinical usefulness and diagnostic accuracy of serum amylase and lipase in the diagnosis of pancreatitis in the current patient population. Secondary aims were to perform a cost analysis of these enzyme levels of patients admitted with abdominal pain to the surgical admissions unit.

Patients and methods

Demographic data

Patients diagnosed with acute pancreatitis at the Queen's Medical Centre Campus, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust during the 1-year period, from January to December 2010, were identified using the hospital's surgical emergency ward database. The medical data of these patients were prospectively reviewed through the hospital's Nottingham Information System (NotIS). Data collected included demography, clinical presentation, laboratory studies, radiological investigations, underlying aetiology, timing of surgery and re-admission rates. Biochemical analyses recorded at presentation included serum amylase (reference range: 0–100 U/l) and lipase (reference range: 0–300 U/l), liver function tests (alanine aminotransferase (reference range: 0–45 U/l), alkaline phosphatase (reference range: 40–130 U/l) and total bilirubin (reference range: 0–21 μmol/l)), full blood count, urea and electrolytes, lactate dehydrogenase (reference range: 220–450 U/l) levels and calcium levels.

Diagnosis of acute pancreatitis

The diagnosis of pancreatitis was based on the following criteria: clinical features (abdominal pain and vomiting) together with the elevation of serum concentrations of pancreatic enzymes (amylase and/or lipase), a value three times greater than normal. At the time of this study, the practice in the Trust was to measure both serum amylase and lipase levels on admission in patients with acute abdominal pain.

All patients diagnosed with acute pancreatitis were then scored using the modified Glasgow Scoring System and had C reactive protein (CRP) levels measured to predict the severity of the attack.7 8 Patients who had a Glasgow score of 3 or more or a CRP level >150 mg/l were predicted to have severe pancreatitis.

All patients underwent radiological imaging to identify gallstones. An abdominal ultrasound (USS) was usually the initial investigation. In cases where other acute abdominal pathology was suspected, an abdominal CT scan was performed. Features to suggest an obstructed biliary system included the presence of dilated common bile duct on USS or CT. In cases with suspected common bile duct stones based on the presence of deranged liver function tests and/or dilated biliary tree on USS or CT, a magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography was performed. This unit's policy is to perform endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography only in cases with confirmed common bile duct stones on radiological imaging, or the presence of cholangitis in patients with acute pancreatitis.

Patients with a clinical history of high alcohol intake, with a negative USS result for gallstones were assumed to have alcohol-induced pancreatitis.

Cost analysis

The cost of a single pancreatic enzyme level (amylase or lipase) was £0.69 and the cost of both amylase and lipase levels when measured together were £0.99.

Statistical analysis

Non-parametric data are presented as median (range), and categorical data as both frequency and proportion (%). Sensitivity and specificity of serum amylase and lipase levels in diagnosing acute and chronic pancreatitis were calculated separately. Patients that did not have acute pancreatitis who had an elevation of three or more times the normal range of amylase or lipase were included in the specificity analysis. The cost of serum pancreatic enzymes measurement was determined in this patient cohort.

Results

Demographic data

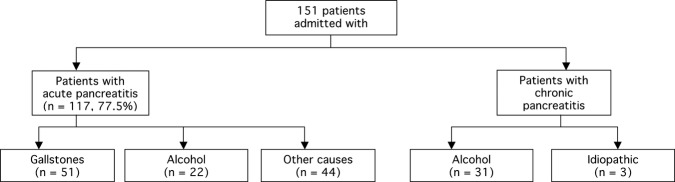

During the study period, 151 patients presented with pancreatitis to the surgical emergency unit, of which 117 (77.5%) patients were admitted with acute pancreatitis (figure 1). There were 34 (22.5%) patients with a history of chronic pancreatitis.

Figure 1.

Aetiology of patients admitted with pancreatitis in this study.

With respect to patients with acute pancreatitis, 68 (58%) patients were males, and the median age of presentation was 46 (17–90) years. There were 29 (19.2%) patients predicted to have severe pancreatitis based on the modified Glasgow Scoring System. The overall median length of hospital stay was 4 (2–90) days, with 14 patients having intensive care and/or high dependency support during their admission. There were three in-patient deaths.

Aetiology

The underlying aetiology for patients with acute pancreatitis were gallstones (n=51, 43.6%), alcohol (n=22, 18.8%), idiopathic (n=37, 31.6%), drug-induced (n=4, 3.4%), pancreatic tumour (n=2, 1.7%) and trauma (n=1, 0.9%).

Amylase and lipase levels

The majority of patients with acute pancreatitis had raised levels of both amylase and lipase (n=113, 97%). Raised lipase only was observed in additional 12% and 23% of patients with gallstone and alcohol-related pancreatitis, respectively. Overall, raised lipase levels were seen between 95% and 100% of patients based on aetiology (table 1). There were no patients with pancreatitis in this cohort that had an elevated amylase level with a normal lipase level. Overall, there were four patients that had normal levels of both lipase and amylase, and these patients were diagnosed with acute pancreatitis following CT scan.

Table 1.

Levels of amylase and lipase with respect to underlying aetiology of acute pancreatitis

| Acute pancreatitis (n=117) | Raised lipase and amylase levels | Raised lipase with normal amylase levels | Normal lipase and amylase levels | Overall raised lipase levels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallstone (n=51) | 43 (84%) | 6 (12%) | 2 (4%) | 49 (96%) |

| Alcohol (n=22) | 17 (77%) | 5 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 22 (100%) |

| Other causes | ||||

| Idiopathic (n=37) | 28 (76%) | 7 (19%) | 2 (5%) | 35 (95%) |

| Drug-induced (n=4) | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) |

| Tumour (n=2) | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) |

| Trauma (n=1) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

A total of 2979 patients with acute abdominal pain were admitted to the surgical admission unit that had serum amylase and lipase measured. There were 18 patients that had an elevation of serum lipase more than three times the upper limit of normal that did not have pancreatitis. Twenty-six patients that did not have pancreatitis had an elevation of serum amylase. All these patients had pancreatitis excluded by CT imaging that detected other pathology (table 2).

Table 2.

Conditions that caused raised levels of lipase and amylase

| Pathology | Raised lipase and amylase levels (n=12) | Raised lipase with normal amylase levels (n=6) | Raised amylase with normal lipase levels (n=14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| Perforated duodenal ulcer | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Cholecystitis | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 1 | 1 | 3 |

With respect to patients admitted with acute pancreatitis, the overall sensitivity and specificity of serum lipase levels in diagnosing pancreatitis was 96.6% and 99.4%, respectively. In comparison with serum amylase levels, the overall sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing acute pancreatitis were 78.6% and 99.1%, respectively.

Cost analysis

The cost of measuring both enzyme levels in patients with pancreatitis was £149.49, compared to £104.19 if serum lipase was measured alone (saving £45.30/year). The total cost of measuring both pancreatic enzymes in all patients (n=2979) admitted with acute abdominal pain through the surgical admissions unit was £2949.21. In contrast, the cost of measuring serum lipase only was £2055.51, a potential saving of £893.70.

Discussion

Accuracy of amylase and lipase levels

The current British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis suggest that clinical presentation with elevation of plasma concentration of pancreatic enzymes, preferably lipase levels, is the cornerstone of diagnosis.6 Various studies have demonstrated that serum lipase levels have better sensitivity and specificity compared to serum amylase levels in diagnosing pancreatitis.5 9 Apple et al4 observed that the sensitivity and specificity of serum lipase levels in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis were 85–100% and 84.7–99.0%, respectively. Although Agrawal et al5 observed a high sensitivity of serum amylase in the diagnosis of pancreatitis of 95–100%, the specificity (70%) was poor. The groups of Agrawal5 and Thomson9 reported a higher sensitivity and specificity in serum lipase levels for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis when compared to serum amylase levels. Other authors have also observed similar results.10 11 In the present study, the overall sensitivity and specificity of serum lipase and amylase levels in diagnosing acute pancreatitis were similar to previous published results. Although the majority of patients with acute pancreatitis had raised levels of both amylase and lipase, raised lipase levels with associated normal amylase concentrations was observed in an additional 12% and 23% of patients with gallstone and alcohol-related pancreatitis, respectively. Hence, patients with pancreatitis would have potentially been missed if serum amylase alone was measured. A high specificity reported in this study may be due to the strict inclusion of only patients without pancreatitis that had an elevation of three times the upper limit of the normal range of pancreatic enzymes. Nevertheless, the above results suggest that measurement of serum lipase levels forms an important part of the diagnostic work-up of patients suspected of having acute pancreatitis, especially in cases where the serum amylase concentrations are normal.

Aetiology and pancreatic enzymes

Both amylase and lipase are released from acinar cells during acute pancreatitis, and their concentration in the serum is used to confirm diagnosis.12 However, the diagnosis of pancreatitis should not solely be based on the arbitrary value of three or four times greater than normal of pancreatic enzymes, but interpreted together with the clinical presentation.13 Amylase levels generally rise within a few hours after the onset of symptoms and return to normal values within 3–5 days, as it has a shorter half-life than lipase. However, amylase levels may remain within normal range in 19% of patients admitted with acute pancreatitis.14 15 In addition, serum amylase levels may be elevated in the absence of acute pancreatitis in patients with decreased glomerular filtration, in diseases of the salivary glands, and in abdominal conditions associated with inflammation, including acute appendicitis, cholecystitis, intestinal obstruction or ischaemia, peptic ulcer disease and gynaecological pathology.16

In contrast to serum amylase, serum lipase concentration is considered a more valuable diagnostic tool, because abnormally elevated values persist for a longer duration, which is an advantage in patients with a delayed presentation.17 In addition, serum lipase is more sensitive in terms of detecting the presence of acute alcohol-induced pancreatitis.18 The present study demonstrated that raised lipase levels were seen in 95–100% of patients depending on aetiology. Seven (22%) additional patients were diagnosed with acute alcohol-induced pancreatitis based on raised lipase levels with an associated normal amylase level. Furthermore, the current UK6 and Japanese19 guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis have emphasised the greater diagnostic accuracy of serum lipase compared to amylase. Although there is good published literature with respect to measurement of lipase levels alone in diagnosing acute pancreatitis, this practice is still not observed in many UK centres. One possible explanation is the easy availability of assessment of amylase levels by local chemical pathology laboratories. 20 In addition, some authors have proposed that both tests are necessary to effectively diagnose pancreatitis,21 while others state that it is not necessary to perform both for diagnostic purposes.22 Although lipase levels are considered to be specific for acute pancreatitis, non-specific elevations of lipase have been reported in almost as many disorders as amylase, thus decreasing its specificity. We would conclude that in agreement with other published studies,4 23 that the combined use of serum amylase and lipase levels does not facilitate the accurate diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.

Cost

The measurement of serum amylase level is still more widely available compared to serum lipase level, and in hospitals where lipase assay is available, both pancreatic enzymes are measured.23 Clearly, the cost of two similar tests seems difficult to justify if they are essentially equivalent and lipase assay appear to be more accurate and clinically useful. In the present study, potentially £893.70 could have been saved over 1 year in patients admitted with acute abdominal pain to the surgical admissions unit. The potential savings observed in this study underestimates the true cost of both amylase and lipase assays as patients admitted in the accident and emergency department and Medical Admissions Unit were not included. At a national level, the potential savings would be a larger amount, with no loss of diagnostic accuracy. At present, it is estimated that acute pancreatitis is responsible for around 25 000 hospital admissions in England, and there is an increase in incidence annually. In just this group of patients, potentially £7500 could be saved annually.

Conclusion

In conclusion, measurement of serum lipase concentrations alone is sufficient to diagnose patients with pancreatitis and substantial savings can be made if measured alone.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Study design by DG, AB and ICC. Data collection by AA and ADR. Manuscript writing by DG, AA, ADR, AB and ICC.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Retrospective study on routine clinical practice.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Toh SK, Phillips S, Johnson CD. A prospective audit against national standards of the presentation and management of acute pancreatitis in the South of England. Gut 2000;46:239–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lund H, Tonnesen H, Tonnesen MH, et al. Long-term recurrence and death rates after acute pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006;41:234–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frey CF, Zhou H, Harvey DJ, et al. The incidence and case-fatality rates of acute biliary, alcoholic, and idiopathic pancreatitis in California, 1994–2001. Pancreas 2006;33:336–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apple F, Benson P, Preese L, et al. Lipase and pancreatic amylase activities in tissues and in patients with hyperamylasemia. Am J Clin Pathol 1991;96:610–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS, Sivaprasad AV. Evaluating tests for acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:356–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UK working party on acute pancreatitis. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut 2005;54(Suppl 3):iii1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blamey SL, Imrie CW, O'Neill J, et al. Prognostic factors in acute pancreatitis. Gut 1984;25:1340–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dervenis C, Johnson CD, Bassi C, et al. Diagnosis, objective assessment of severity, and management of acute pancreatitis. Santorini consensus conference. Int J Pancreatol 1999;25:195–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomson HJ, Obekpa PO, Smith AN, et al. Diagnosis of acute pancreatitis: a proposed sequence of biochemical investigations. Scand J Gastroenterol 1987;22:719–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nordestgaard AG, Wilson SE, Williams RA. Correlation of serum amylase levels with pancreatic pathology and pancreatitis etiology. Pancreas 1988;3:159–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orebaugh SL. Normal amylase levels in the presentation of acute pancreatitis. Am J Emerg Med 1994;12:21–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matull WR, Pereira SP, O'Donohue JW. Biochemical markers of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Pathol 2006;59:340–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toouli J, Brooke-Smith M, Bassi C, et al. Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;17(Suppl):S15–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clavien PA, Robert J, Meyer P, et al. Acute pancreatitis and normoamylasemia. Not an uncommon combination. Ann Surg 1989;210:614–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winslet M, Hall C, London NJ, et al. Relation of diagnostic serum amylase levels to aetiology and severity of acute pancreatitis. Gut 1992;33:982–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swensson EE, Maull KI. Clinical significance of elevated serum and urine amylase levels in patients with appendicitis. Am J Surg 1981;142:667–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sternby B, O'Brien JF, Zinsmeister AR, et al. What is the best biochemical test to diagnose acute pancreatitis? A prospective clinical study. Mayo Clin Proc 1996;71:1138–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gumaste V, Dave P, Sereny G. Serum lipase: a better test to diagnose acute alcoholic pancreatitis. Am J Med 1992;92:239–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koizumi M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. JPN Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: diagnostic criteria for acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2006;13:25–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yadav D, Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS. A critical evaluation of laboratory tests in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1309–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank B, Gottlieb K. Amylase normal, lipase elevated: is it pancreatitis? A case series and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:463–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treacy J, Williams A, Bais R, et al. Evaluation of amylase and lipase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. ANZ J Surg 2001;71:577–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith RC, Southwell-Keely J, Chesher D. Should serum pancreatic lipase replace serum amylase as a biomarker of acute pancreatitis? ANZ J Surg 2005;75:399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.