Abstract

Objectives

To examine reductions in suicidal ideation among a sample of patients who were prescribed an internet cognitive behavior therapy (iCBT) course for depression.

Design

Effectiveness study within a quality assurance framework.

Setting

Primary care.

Participants

299 patients who were prescribed an iCBT course for depression by primary care clinicians.

Intervention

Six lesson, fully automated cognitive behaviour therapy course delivered over the internet. Primary outcome: suicidal ideation as measured by question 9 on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).

Results

Suicidal ideation was common (54%) among primary care patients prescribed iCBT treatment for depression but dropped to 30% post-treatment despite minimal clinician contact and the absence of an intervention focused on suicidal ideation. This reduction in suicidal ideation was evident regardless of sex and age.

Conclusions

The findings do not support the exclusion of patients with significant suicidal ideation.

Keywords: Mental Health, Primary Care, Psychiatry

Article summary.

Article focus

The reduction of suicidal ideation among patients treated for depression using internet cognitive behaviour therapy (iCBT) in clinical practice.

Key messages

Suicidal ideation is common among primary care patients prescribed iCBT for depression.

After treatment with iCBT, suicidal ideation decreased significantly.

The continued exclusion of these patients from research studies and iCBT is no longer justified.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Evidence is needed to see if the changes in suicidal ideation are sustained over time.

Patients who say they feel they would be ‘better off dead’ worry clinicians and, for that matter, research ethics committees approving depression trials, especially trials over the internet. As a consequence, patients reporting suicidal ideas are often excluded from internet treatment trials.1–3 Given that suicidal thoughts are an integral part of depression we sought data to provide a rational basis for inclusion/exclusion of people with suicidal ideas.

Rates of suicide can be reduced through treatment of depression or reduction in access to the means for suicide.4–6 The efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in treating depression has been established. Suicidal ideas and attempts decrease, commensurate with reductions in depressive symptomatology.7–15 These studies have all been conducted within a clinical trial framework among depressed patients selected for their high suicide risk. To our knowledge, there is currently no evidence regarding the effectiveness of CBT or internet CBT (iCBT) in reducing suicidal ideation in the depressed patient seeking treatment in primary care, and no data to inform inclusion/exclusion criteria in clinical trials.

We have previously reported from two randomised controlled trials that the progress of patients receiving the iCBT course used in this study was significantly better than the progress of a waitlist control group.1 2 We have also reported from quality assurance studies that when these courses were used routinely by primary care clinicians that effectiveness was comparable to the efficacy and that adherence rates of 60% could be achieved.16 17 The aim of the current quality assurance study is to examine reductions in suicidal ideation among a sample of patients who were prescribed an iCBT course for depression by primary care clinicians.

Method

Sample

Primary care physicians prescribed the internet depression course for patients they deemed suitable.1 They were advised to exclude people who were ‘actively suicidal’. As part of a routine quality assurance exercise we analysed the progress of the 299 primary care patients who completed the six-lesson iCBT depression course between April 2009 and May 2011.1 Data gathered were confined to measures used as a routine to inform practitioners about the progress of their patients. All patients agreed that their pooled data could be used for quality assurance purposes. This paper was written as part of the Quality Assurance activities of St Vincent's Hospital with whom the draft of the paper was lodged prior to submission.

Intervention

The iCBT depression course consists of six lessons covering psycho-education, behavioural activation, cognitive restructuring, problem-solving, graded exposure and relapse prevention.1 2 Content is presented in the form of an illustrated story in which the character gains mastery over their depressive symptoms. At the end of each illustrated lesson the patient downloads ‘homework,’ comprising a summary of the lesson content, and activities to be completed that translate the skills learnt in the lesson to their own lives. Automatic emails are also sent congratulating patients when they complete lessons. Clinicians are advised to contact patients at least twice during the course.

Outcome measures

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a brief nine-item measure of depression severity.18 The nine-items assess Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV Criterion A for major depressive disorder (MDD). Patients rate each item in terms of the frequency of symptoms over the past 2 weeks, on a four-point scale (0=not at all, 1=several days, 2=more than half of the days and 3=nearly everyday). Scores can range from 0 to 27, with higher levels representing higher symptom severity. Cut points for MDD have been established as follows: 0–9=well or subthreshold, 10–14=mild, 15–19=moderate and 20–27=severe depression.19. Suicidal ideation was measured by question 9 from the PHQ-9 which asks about the frequency of suicidal ideation (‘thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way’) in the previous 2 weeks using the above four-point scale. The PHQ-9 has been shown to demonstrate adequate reliability, convergent/discriminant validity and responsiveness to change in previous studies of iCBT,20 with a Cronbach's α of 0.89 in the current sample.

Statistical analysis

Changes in participants' PHQ-9 scores from pre-treatment to post-treatment were analysed using a paired samples t test. Multivariate linear regression controlling for baseline PHQ-9 scores was used to investigate the effect of sex and age on post-treatment PHQ-9 scores. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to analyse differences in suicidal ideation in response to treatment. Multinomial logistic regression controlling for baseline suicidality investigated the effect of sex and age on post-treatment suicidal ideation. An α of 0.05 was used to test statistical significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics

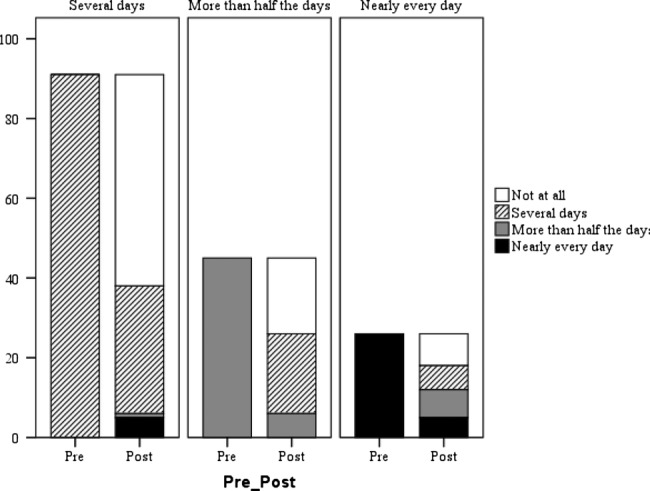

The mean age of the 299 patients who completed the six lesson course was 43 years, 56% female. The mean baseline PHQ-9 score was 14.3 with 83 patients scoring 0–9 (well or subthreshold MDD), and 216 scoring 10–27 and likely to meet criteria for MDD (n=72 mild, n=70 moderate and n=74 severe MDD). Prior to the start of lesson 1, 54% of the patients (162/299) reported some level of suicidal ideation on question 9 of the PHQ-9: 30% (91/299) had thought about it for several days in the past 2 weeks, 15% (45/299) thought about it more than half the days and 9% (26/299) indicated that they thought about suicide nearly everyday.

Post-treatment outcomes

From pre-treatment to post-treatment there was a significant reduction in PHQ-9 scores (t(298)=18.1, p<0.001), with PHQ-9 scores reducing by 6.2 points on average (SD=5.9; d=0.98 (95% CI)). A multivariate linear regression controlling for baseline PHQ-9 scores indicated that age and gender were not statistically significant predictors of post-treatment PHQ-9 scores. The reduction in suicidal ideation was considerable and evident at all frequencies, with only 30% (90/299) reporting suicidal ideation at lesson six (see figure 1). A Wilcoxin signed-rank test showed a statistically significant change in suicidal ideation (Z=−7.9, p<0.001, r=0.5) as measured by question 9 on the PHQ-9 (table 1), with median scores of 1 (‘several days’) preintervention and 0 (‘not at all’) postintervention. A multinomial logistic regression controlling for baseline suicidal ideation scores indicated that age and gender were not statistically significant predictors of postintervention suicidal ideation scores. Patient reported a median of 1 (range 0–2) clinician contacts during the course (table 1).

Figure 1.

Frequency of suicidal thoughts (number of patients) before and after treatment for depression.

Table 1.

Frequency of suicidal thoughts as measured by Question 9 of the PHQ-9

| Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preintervention | 137 (45.8%) | 91 (30.4%) | 45 (15.15%) | 26 (8.7%) |

| Postintervention | 209 (69.9%) | 66 (22.1%) | 14 (4.7%) | 10 (3.3%) |

PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Discussion

Suicidal ideation was common (54%) among primary care patients prescribed treatment for depression but dropped to 30% post-treatment despite minimal clinician contact and the absence of an intervention focused on suicidal ideation. This reduction in suicidal ideation was evident regardless of sex and age. To our knowledge, this is the first study to document an association between iCBT for depression and reductions in suicidal ideation.

The benefits in reducing suicidal ideas are clear. Suicidal behaviour lies on a continuum from thoughts, through intent and planning, to attempt. In the general population it has been shown that 34% of people with ideas develop suicidal plans, and that these plans lead to suicide attempts in 72% of cases.15 21 That is, one in four people who report suicidal ideation will transition to a suicide attempt, most within the first year of ideation onset.21 Suicide attempts are significant predictors of subsequent completed suicide. Suicidal ideas are distressing and dangerous, and therefore an important target for treatment.

We have conducted two randomised controlled trials of our iCBT programme for depression.1 2 In the first trial, 33% of applicants were excluded due to suicidal ideation. In the second, 23% were excluded due to suicidal ideation. On the basis of the current results it is now difficult to justify excluding patients from clinical trials on the basis of their high suicidal ideation scores when iCBT can reduce them quickly and effectively.

Limitations

Although the item from the PHQ-9 assessed the presence and frequency of suicidal ideation, it did not assess the intensity of the ideation, controllability, intention to act on thoughts, nor suicide plans or means. Evidence is also needed to understand whether the changes in suicidal ideation observed in this study are sustained over time. In addition, there was no control sample, meaning that treatment effects could be attributable to regression to the mean, spontaneous remission or placebo effects, rather than the intervention per se. The fact that benefits were observed among patients at different levels of baseline risk indicates that regression to the mean may not underlie treatment effects. However, it is not possible to fully examine the influence of these alternative factors on the outcomes of interest. It was also not possible to establish whether treatment effects were sustained over time due to the lack of follow-up data. Finally, the lack of formal exclusion criteria means that patients may have been using adjunctive treatments which contributed to the magnitude of treatment effects. While the limitations outlined above may be critical within the context of an efficacy trial, they are endemic to effectiveness research.

Conclusion

Both suicidal ideation and depressive symptomatology were reduced considerably following completion of a six-lesson iCBT course for depression. This is the first study to demonstrate this association in primary care. At present, it is routine to exclude patients with frequent suicidal ideation from participating in iCBT. This study provides evidence for change.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SW drafted the initial manuscript, prepared and cleaned the data, and conducted initial data analysis. LM and JN conducted further statistical analysis. GA supervised and took responsibility for the data. All four authors contributed to revised drafts.

Funding: SW and JN were supported by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. LM was supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Capacity Building Grant.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Data gathered was confined to measures used as a routine to inform practitioners about the progress of their patients. All patients agreed that their pooled data could be used for quality assurance purposes. This paper was written as part of the Quality Assurance activities of St Vincent's Hospital with whom the draft of the paper was lodged prior to submission.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Perini S, Titov N, Andrews G. Clinician-assisted internet-based treatment is effective for depression: randomized controlled trial. Australas Psychiatry 2009;43:571–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Titov N, Andrews G, Davies M, et al. Internet treatment for depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance. PLoS One 2010;5:e10939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson R, Sjöberg E, Sjögren M, et al. Tailored vs. standardized internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for depression and comorbid symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2012;7:e36905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, et al. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA 2005;293:2487–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, et al. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002 [PubMed]

- 6.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies. JAMA 2005;294:2064–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans K, Tyrer P, Catalan J, et al. Manual-assisted cognitive-behavior therapy (MACT): a randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention with bibliotherapy in the treatment of recurrent deliberate self-harm. Psychol Med 1999;29:19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawton K, Bancroft J, Catalan J, et al. Domiciliary and out-patient treatment of self-poisoning patients by medical and non-medical staff. Psychol Med 1981;11:169–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawton K, Townsend E, Arensman E, et al. Psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for deliberate self harm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1999;4:CD001764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liberman RP, Eckman T. Behavior therapy vs insight-oriented therapy for repeated suicide attempters. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLeavey BC, Daly RJ, Ludgate JW, et al. Interpersonal problem-solving skills training in the treatment of self-poisoning patients. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1994;24:382–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patsiokas AT, Clum GA. Effects of psychotherapeutic strategies in the treatment of suicide attempters. Psychother Theory Res Pract Train 1985;22:281 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salkovskis PM, Atha C, Storer D. Cognitive-behavioural problem solving in the treatment of patients who repeatedly attempt suicide. A controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 1990;157:871–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sande R, Buskens E, Allart E, et al. Psychosocial intervention following suicide attempt: a svstematic review of treatment interventions. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997;96:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarrier N, Taylor K, Gooding P. Cognitive-behavioral interventions to reduce suicide behavior. Behav Modif 2008;32:77–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sunderland M, Wong N, Hilvert-Bruce Z, et al. Investigating trajectories of change in psychological distress amongst patients with depression and generalised anxiety disorder treated with internet cognitive behavioural therapy. Behav Res Ther 2012;50:374–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilvert-Bruce Z, Rossouw PJ, Wong N, et al. Adherence as a determinant of effectiveness of internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety and depressive disorders. Behav Res Ther 2012;50:463–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32:345–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Titov N, Dear BF, McMillan D, et al. Psychometric comparison of the PHQ-9 and BDI-II for measuring response during treatment of depression. Cogn Behav Ther 2011;40:126–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.