Abstract

Objectives

To compare the risk profile of women giving birth in private and public hospitals and the rate of obstetric intervention during birth compared with previous published rates from a decade ago.

Design

Population-based descriptive study.

Setting

New South Wales, Australia.

Participants

691 738 women giving birth to a singleton baby during the period 2000 to 2008.

Main outcome measures

Risk profile of women giving birth in public and private hospitals, intervention rates and changes in these rates over the past decade.

Results

Among low-risk women rates of obstetric intervention were highest in private hospitals and lowest in public hospitals. Low-risk primiparous women giving birth in a private hospital compared to a public hospital had higher rates of induction (31% vs 23%); instrumental birth (29% vs 18%); caesarean section (27% vs 18%), epidural (53% vs 32%) and episiotomy (28% vs 12%) and lower normal vaginal birth rates (44% vs 64%). Low-risk multiparous women had higher rates of instrumental birth (7% vs 3%), caesarean section (27% vs 16%), epidural (35% vs 12%) and episiotomy (8% vs 2%) and lower normal vaginal birth rates (66% vs 81%). As interventions were introduced during labour, the rate of interventions in birth increased. Over the past decade these interventions have increased by 5% for women in public hospitals and by over 10% for women in private hospitals. Among low-risk primiparous women giving birth in private hospitals 15 per 100 women had a vaginal birth with no obstetric intervention compared to 35 per 100 women giving birth in a public hospital.

Conclusions

Low-risk primiparous women giving birth in private hospitals have more chance of a surgical birth than a normal vaginal birth and this phenomenon has increased markedly in the past decade.

Keywords: Public Health

Article summary.

Article focus

To compare the rate of obstetric intervention during birth among low-risk women giving birth in public and private hospitals in New South Wales.

To compared these rates with previous published data from a decade ago.

To examine the impact of introducing interventions in labour on normal vaginal birth rates in the different hospitals.

Key messages

Among low-risk women rates of obstetric intervention were highest in private hospitals and lowest in public hospitals.

Low-risk primparous and multiparous women, respectively, had a 20% and 15% lower chance of a normal vaginal birth if they gave birth in a private hospital

Over the past decade, interventions have increased for low-risk women receiving public hospital care by over 5%, and by over 10% in private hospitals.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strength of this study lies in the large sample size of over half a million women.

Limitations are the restricted number of variables that are included and the scarcity of specific information on potential confounders.

Body mass index and key sociodemographic risk factors could not be controlled for and this would have added risk to women giving birth in public hospitals.

Introduction

In Australia, the national statistics reveal that 34% of women giving birth in 2009 elected private status, with 30% of women giving birth in private hospitals directly under private obstetric care.1 The remaining women were public patients and received a combination of midwifery and medical care in public hospitals, with around 4% of privately insured women also giving birth in a public hospital. At a national level the intervention rates in childbirth, such as caesarean section, are significantly higher in the private sector (43% vs 28%) and the rates of normal vaginal birth significantly lower (43% vs 62%).1 The overall caesarean section rate in Australia (32%) is significantly higher than the OECD average of 25.7% of births.2 Despite the rising intervention rates over the past decade the perinatal death rate has not shown a corresponding decline. There is also growing concern that the short-term and long-term morbidity associated with major obstetric interventions such as caesarean may not be insignificant for the mother3 and the baby.4

Several resource-rich countries have responded to the public health concern posed by high caesarean section rates by implementing policies designed to increase the rate of normal vaginal birth. In the UK,5 the USA6 and New South Wales (NSW)7 government policy has been implemented with the explicit aim of increasing the vaginal birth rate and decreasing the caesarean section rate.7 Despite these efforts, intervention in childbirth continues to increase in Australia and many other developed nations.

The cost to the tax payer of the rising intervention in childbirth is significant.8 9 A recent Australian randomised controlled trial of caseload midwifery care for women in all risk categories showed that care in less interventionist models was as safe and significantly less costly than routine public hospital care (in press). In 2000 Roberts, Tracy and Peat published a paper examining rates of obstetric intervention among private and public women giving birth in NSW during the years 1996 and 1997. NSW is the most populous state in Australia and broadly representative of the national population. The Roberts et al10 study found that the number of women classified as low risk was similar (48%) among those receiving private obstetric care and those receiving standard public hospital care. Rates of obstetric intervention among these low-risk women were however significantly higher among women giving birth under private obstetric care. Among the low-risk primiparous women giving birth during this period, more women giving birth in private hospitals compared to public hospitals had forceps and vacuum deliveries (34% vs 17%), induction of labour (26% vs 16%), caesarean section (16% vs 10%), epidural (51% vs 25%) and episiotomy (47% vs 29%).10 The small number of private women who gave birth in public hospitals had lower intervention rates than in private hospitals and higher intervention rates than women who were not privately insured.

We aimed to compare the risk profile of women giving birth in private and public hospitals in NSW between 2000 and 2008; to determine the rates of obstetric intervention during birth for these two groups of low-risk women and to see whether there has been a change in the profile and intervention rates in the past decade.

Methods

Data sources

Perinatal data recorded in the NSW Midwives Data Collection (MDC) for the time period 1 July 2000 till 30 June 2008 was provided by NSW Department of Health. The MDC is a population-based surveillance system containing maternal and infant data on all births of greater than 400 g birth weight or 20 weeks gestation. Hospitals are coded either as private or public in the data set. However, the data identifying women who received care in public hospitals under private accommodation status is no longer collected as it had been in the years 1996–1997 and for this reason patients who are under private obstetric care in public hospitals are not able to be differentiated from their public counterparts, so for this study we analysed the data by hospital (private/public). The previous study published in 200010 showed that there was a moderating factor on intervention rates when women with private insurance status gave birth in a public hospital, leading to lower intervention rates than when they gave birth in private hospitals.

The linked dataset was provided by the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL) following approval by the Data Custodian (NSW Health).

Subjects

Maternal factors available for analysis included: age, parity, pre-existing (pre-pregnancy diabetes and chronic hypertension) and pregnancy-related medical conditions (pregnancy-related diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy), labour onset, delivery type, pain relief utilised and perineal status. Labour onset was categorised as spontaneous or induced and/or augmented by means of prostaglandins, synthetic oxytocins and/or mechanical devices but not artificial rupture of membranes alone. When a caesarean section was performed before the onset of labour the labour was recorded as ‘No Labour’. Neonatal factors included birth weight, gestation at birth, presentation and Apgar scores.

The ‘standard primipara’ is defined as a primiparous woman aged 20–34 years, who had no pre-existing or pregnancy-related medical conditions, gave birth at 37–41 weeks gestation to a fetus in a cephalic presentation within the 10th and 90th centiles for birth weight. The ‘standard multipara’ was a multiparous woman aged 20–34 years, who had no pre-existing or pregnancy-related medical conditions, gave birth at 37–41 weeks gestation of a fetus in a cephalic presentation within the 10th and 90th centiles for birth weight.10–12 In both definitions we included ‘non smoking’.

We examined a pre-determined and previously published ‘cascade of intervention.’10 13 14 These events occur in a chronological sequence during labour and birth.

Data analysis

Contingency table analyses were utilised to examine differences between the two groups based on hospital type. A significance level of <0.01 was set due to the nature of population data and the significant size of the dataset. Age differed significantly between the two groups and as a potential confounder, age was adjusted utilising the Direct Standardisation method, with the pooled low-risk population as the standard. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS V.19.

Results

There were 691 738 births during the period 2000–2008. This included 163 759 births in private hospitals and 527 979 births in public hospitals. The frequency of women classified as low risk giving birth in private hospitals compared to public hospitals was similar for primiparous women (18.4% vs 17.9%) but lower for multiparous women (18.6% vs 26.3%) due to the larger proportion of women giving birth in the private setting over the age of 34 years.

Overall women who gave birth in private hospitals were more likely to be over 35 years of age and have a baby at or above the 90th centile for birth weight and gestation. They were less likely to have four or more children, have a pregnancy-related medical condition, have a baby weighing less than the 10th centile, weighing under 2500 g, born at less than 37 weeks gestation, have a pregnancy before the age of 20 or have a pregnancy lasting beyond 41 weeks (table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency (%) of maternal and infant characteristics—all women in cohort

| Private hospital n=163759 (%) | Public hospital n=527979 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <20 | 0.1 | 3.2 |

| 20–34 | 68 | 78.1 |

| >35 | 31.9 | 18.8 |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 44.6 | 40.9 |

| 1–4 | 55 | 57.2 |

| >4 | 0.4 | 2 |

| Pre-existing medical condition | ||

| Yes | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| No | 98.6 | 98.5 |

| Pregnancy medical complications | ||

| Yes | 7.3 | 10.3 |

| No | 92.7 | 89.7 |

| Presentation cephalic | 94.9 | 95.4 |

| Gestational age percentile | ||

| <10 | 6.4 | 9.9 |

| 10–24.9 | 13.5 | 15.8 |

| 25–74.9 | 52 | 49.9 |

| 75–89.9 | 16.9 | 14.6 |

| 90–100 | 11.1 | 9.9 |

| Birth weight (g) | ||

| <2500 | 2.5 | 5.6 |

| 2500–4499 | 95.9 | 92.4 |

| ≥4500 | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | ||

| <37 | 9.1 | 11.5 |

| 37–41 | 90.2 | 86.1 |

| ≥41 | 0.6 | 2.4 |

| Low risk women | ||

| Primparas | 18.4 | 17.9 |

| Multiparas | 18.6 | 26.3 |

Table 2 shows the rate of obstetric intervention among the 30 152 low-risk primiparous women who gave birth in a private hospital and the 94 279 low-risk primiparous women who gave birth in a public hospital. Low-risk primiparous women giving birth in a private hospital compared to a public hospital had higher rates of induction (31% vs 23%), instrumental birth (29% vs 18%), caesarean section (27% vs 18%), epidural (53% vs 32%) and episiotomy (28% vs 12%) and they had a 20% lower normal vaginal birth rate (44% vs 64%). Intervention rates for low-risk primiparous women had increased substantially between 1996/1997 and 2000/2008, except for episiotomy and forceps delivery where there had been a decline.

Table 2.

Birth characteristics and outcomes among primiparas at low risk for 1996/1997 and 2000/2008

| 1996/1997 Private hospitals (n=6548) (%) | 2000–2008 Private hospitals (n=30152) (%) | 1996/1997 Public hospitals (n=20354) (%) | 2000–2008 Public hospitals (n=94279) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | ||||

| 20–24 | 10.6 | 7 | 40.6 | 33.1 |

| 25–29 | 48.9 | 43.1 | 40 | 41.3 |

| 30–34 | 40.6 | 49.9 | 19.3 | 25.6 |

| Type of labour | ||||

| Spontaneous | 47 | 32.1 | 63.8 | 48.4 |

| Augmented | 23.1 | 28.1 | 19.7 | 25.8 |

| Induced | 25.7 | 30.9 | 15.7 | 22.8 |

| No labour | 4.1 | 8.9 | 1.4 | 3 |

| Delivery | ||||

| Vaginal | 49.7 | 43.9 | 72.6 | 63.8 |

| Forceps | 22.5 | 11.2 | 10.5 | 6.3 |

| Vacuum | 11.4 | 17.7 | 6.8 | 12.1 |

| Caesarean section before labour | 4.1 | 8.9 | 1.5 | 3 |

| Caesarean section after labour | 12.3 | 18.2 | 8.5 | 14.8 |

| Epidural | 50.8 | 53.3 | 25.1 | 32.2 |

| Episiotomy | 46.6 | 27.7 | 28.6 | 11.8 |

| Severe perineal trauma | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 1.6 |

| Apgar score <7 at 5 min | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

Table 3 shows the rate of intervention among 30 512 low-risk multiparous women who gave birth in a private hospital compared to 138 897 low-risk women who gave birth in a public hospital. Low-risk multiparous women had higher rates of instrumental birth (7% vs 3%), caesarean section (27% vs 16%), epidural (35% vs 12%) and episiotomy (8% vs 2%) and 15% lower normal vaginal birth rates (66% vs 81%) when giving birth in a private hospital. Intervention rates for low-risk multiparous women had increased substantially between 1996/1997 and 2000/2008, except for episiotomy and forceps delivery where there had been a decline. There appears to have been an increase in severe perineal trauma among low-risk multiparous women in private as well as public hospitals since 1996/1997.

Table 3.

Birth characteristics and outcomes among multiparas at low risk for 1996/1997 and 2000/2008

| 1996/1997 Private hospitals (n=8439) (%) | 2000–2008 Private hospitals (n=30512) (%) | 1996/1997 Public hospitals (n=35825) (%) | 2000–2008 Public hospitals (n=138897) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | ||||

| 20–24 | 3.5 | 2.4 | 22.7 | 20.3 |

| 25–29 | 34.5 | 29.6 | 41.7 | 41.5 |

| 30–34 | 61.9 | 67.9 | 35.6 | 38.2 |

| Type of labour | ||||

| Spontaneous | 55.3 | 32.3 | 76.8 | 57 |

| Augmented | 7.2 | 16.7 | 4.8 | 13.3 |

| Induced | 22.9 | 29.5 | 12.9 | 18.4 |

| No labour | 14.5 | 21.4 | 6.5 | 11.2 |

| Delivery | ||||

| Vaginal | 74.3 | 66.3 | 88.0 | 81.2 |

| Forceps | 4.2 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.8 |

| Vacuum | 3.4 | 5.2 | 1.3 | 2.3 |

| Caesarean section before labour | 14.5 | 21.4 | 6.5 | 11.2 |

| Caesarean section after labour | 3.5 | 5.2% | 2.9 | 4.5 |

| Epidural | 31.3 | 35.9 | 9.2 | 11.8 |

| Episiotomy | 19.2 | 8.3 | 7 | 2.1 |

| Third degree tear | 0.2 | 1 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| Apgar score <7 at 5 min | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

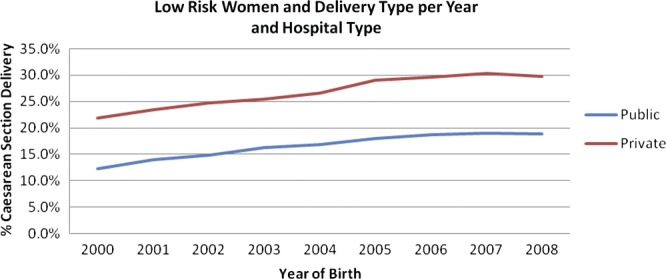

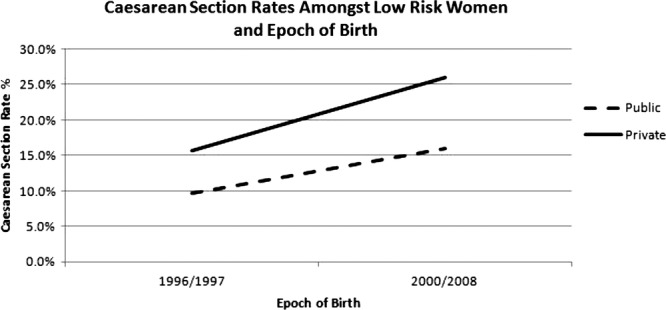

Over the past decade, the rate of birth interventions such as caesarean section for low-risk women had nearly doubled in private hospitals (figures 1 and 2). Obstetric interventions steadily increased among low-risk women receiving public hospital care during this period by more than 5%, and by over 10% among women receiving private obstetric care in private hospitals. Table 4 shows the cascade effect of obstetric interventions among low-risk primiparous women when standardised for age. There was a notable increase in intervention and decline in normal vaginal birth as the interventions accumulated (induction of labour, epidural and augmentation of labour). Low-risk primiparous women giving birth in a private hospital were more likely to have interventions during labour and more likely to have operative births. Among low-risk primiparous women giving birth in private hospitals 15 per 100 women had a vaginal birth with no obstetric intervention compared to 35 per 100 women giving birth in a public hospital. This showed a reduction in rates of vaginal birth with no obstetric intervention compared to the previous study (18 per 100 women in private hospitals and 39 per 100 women in public hospitals)10 (figures 1 and 2). Among primiparous women giving birth in private hospitals that had an epidural the most likely outcome was an instrumental birth and this rate was higher than for women giving birth in a public hospital (40% vs 30%). The likelihood of having a vaginal birth also dropped significantly for these women (36% vs 47%). This difference was less dramatic with multiparous women but the high rates of pre-labour caesarean section among the women giving birth in a private hospital impacted on these outcomes. Among low-risk multiparous women, 35 per 100 women had a vaginal birth with no obstetric intervention compared to 65 per 100 women giving birth in a public hospital (table 5).

Figure 1.

Low-risk women and delivery type per year and hospital type.

Figure 2.

Caesarean section rates among low-risk women giving birth in private and public hospitals in 1996–1997 compared to 2000–2008.

Table 4.

Rates per 100 women for obstetric intervention among primiparas at low risk for 1996/1997 and 2000/2008—age standardised

| Labour management before birth | Management at birth | 1996/1997 Private | 2000–2008 Private | 1996/1997 Public | 2000–2008 Public |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No epidural, no induction | No episiotomy | ||||

| Vaginal birth | 55.5 | 55.2 | 71.4 | 75.6 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 3.9 | 7.2 | 3.1 | 4.9 | |

| Episiotomy | |||||

| Vaginal birth | 21.3 | 20.7 | 14.6 | 9.4 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 15.9 | 11.1 | 7.9 | 5.5 | |

| Caesarean section after labour | 3.4 | 5.7 | 3.1 | 4.7 | |

| Subgroup rate | 32.5 | 25.3 | 54 | 45.9 | |

| No epidural, induction | No episiotomy | ||||

| Vaginal birth | 45.7 | 41.6 | 56.4 | 59 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 6 | 9.8 | 4.3 | 7.7 | |

| Episiotomy | |||||

| Vaginal birth | 22.3 | 19.3 | 16.8 | 11.1 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 16.7 | 18.4 | 14.3 | 8.7 | |

| Caesarean section after labour | 9.3 | 11 | 8.2 | 13.5 | |

| Subgroup rate | 17.8 | 17.4 | 9.1 | 19.7 | |

| Epidural, no induction | No episiotomy | ||||

| Vaginal birth | 27.8 | 26.1 | 37.8 | 41.9 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 15.7 | 17.3 | 8.3 | 13.3 | |

| Episiotomy | |||||

| Vaginal birth | 7.2 | 10.1 | 9.5 | 5.5 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 33.8 | 22.8 | 27.4 | 16.3 | |

| Caesarean section after labour | 15.6 | 23.8 | 17 | 23 | |

| Subgroup rate | 15.2 | 16.5 | 19 | 10.5 | |

| Epidural, induction | No episiotomy | ||||

| Vaginal birth | 24.5 | 22.7 | 34.1 | 34.8 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 14.7 | 15.1 | 9.5 | 13.7 | |

| Episiotomy | |||||

| Vaginal birth | 9 | 9.4 | 6.7 | 5.7 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 32.3 | 21.5 | 24.4 | 15 | |

| Caesarean section after labour | 19.5 | 31.2 | 25.3 | 30.9 | |

| Subgroup rate | 31 | 31.9 | 16.3 | 20.9 | |

| Rate for caesarean section before labour | 3.4 | 8.9 | 1.6 | 3 | |

Table 5.

Rates per 100 women for obstetric intervention among multiparas at low risk for 1996/1997 and 2000/2008—age standardised

| Labour management | Management at birth | 1996/1997 Private | 2000–2008 Private | 1996/1997 Public | 2000–2008 Public |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before birth no epidural, no induction | No episiotomy | ||||

| Vaginal birth | 82.5 | 82.6 | 92 | 92.6 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 1.6 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 1 | |

| Episiotomy | |||||

| Vaginal birth | 11.9 | 9.9 | 4.9 | 2.8 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 1.3 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 | |

| Caesarean section after labour | 2.7 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 3 | |

| Subgroup | 47.6 | 35.2 | 72.4 | 63 | |

| No epidural, induction | No episiotomy | ||||

| Vaginal birth | 79.3 | 80.8 | 87.9 | 89.8 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 1.5 | 4.2 | 1.3 | 2 | |

| Episiotomy | |||||

| Vaginal birth | 15.5 | 10.9 | 6.3 | 3.5 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.8 | |

| Caesarean section after labour | 1.8 | 2.3 | 3 | 3.9 | |

| Subgroup rate | 19.9 | 18.4 | 14.9 | 16.3 | |

| Epidural, no induction | No episiotomy | ||||

| Vaginal birth | 51.4 | 54.8 | 61 | 65.1 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 10.4 | 10.6 | 5.2 | 7.5 | |

| Episiotomy | |||||

| Vaginal birth | 11.5 | 10.3 | 3.8 | 3.8 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 11.2 | 6 | 8.2 | 4.7 | |

| Caesarean section after labour | 15.4 | 18.3 | 21.8 | 18.9 | |

| Subgroup rate | 8.1 | 10.6 | 3.4 | 4.8 | |

| Epidural, induction | No episiotomy | ||||

| Vaginal birth | 55.2 | 64.3 | 62.3 | 68.3 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 13.7 | 11.2 | 9.2 | 9.6 | |

| Episiotomy | |||||

| Vaginal birth | 14 | 11.4 | 5.3 | 4.2 | |

| Forceps or vacuum | 8.9 | 5.3 | 8 | 3.8 | |

| Caesarean section after labour | 8.2 | 7.8 | 15.2 | 14.1 | |

| Subgroup rate | 11.2 | 14.4 | 3 | 4.6 | |

| Rate for caesarean section before labour | 13 | 21.5 | 6.3 | 11.2 | |

The caesarean section rate has increased for all low-risk women giving birth in NSW between 1996/1997 and 2008 but there appears to be a slight levelling-off in the rate since 2006 (figure 1). There is a significant difference between public and private caesarean section rates at both time points as well as a significant increase within settings across time (<0.001). This equates to an 11.1% increase in the caesarean section rate in the private hospital setting compared to a 6.7% rise in the public setting between the earlier and the present studies (figure 2).

Discussion

The significance of this study lies in the large sample size and the finding that regardless of the low-risk status of these women the intervention rates such as caesarean section and instrumental birth have continued to rise slowly year after year. These rates do not appear to be parallel to or be associated with a better infant outcome. The NSW rate of perinatal mortality was between 8.6 and 9.6 per 1000 births between 2000 and 2005 and between 8.7 and 9 per 1000 births between 2005 and 200915 16. A recent randomised controlled trial of case load midwifery (continuity of carer) for low-risk women compared to standard care offered in a large teaching hospital in Australia found a 22% reduction in caesarean section rate under continuity of midwifery care with no difference in perinatal mortality.17 This indicates that changes in caesarean section rates can occur with little impact on perinatal mortality. The difference between private and public maternity care suggests that the rates are potentially associated with variations in practitioner behaviour as opposed to the poor health of women. Other authors have also asserted that rising caesarean section rates centre on clinician preferences. Leitch and Walker18 stated that while indications for caesarean section have not changed much over time there has been lowering in the overall threshold concerning the decision to carry out a caesarean.

Our study is limited to providing a snapshot view of the birth outcomes in a defined time period. However, this study repeats the analysis of a paper published in 2000 providing the reader with a more detailed picture of the current state of obstetric intervention in NSW. The advantages of using population-based datasets, such as the MDC, include the size of the dataset and the guaranteed accuracy of a validated dataset. The limitations are the restricted number of variables that are included and the scarcity of specific information on potential confounders. Previous validation studies have reported high levels of data accuracy for the majority of diagnoses and procedures conducted during labour and delivery in the state-wide data base,19 20 although the recording of medical conditions are overall generally underreported.19 21 While we could not control for obesity due to lack of reliable data, women who have private health insurance have lower rates of obesity and higher socioeconomic status hence these health disadvantages are most likely over-represented in the public women.22 There are also several other sociodemographic factors we could not control for such as education and income that increase risk for the women giving birth in public hospitals.

The overall proportions of women classified as low risk who gave birth in private and public hospitals in NSW during the years 2000–2008 were similar for primiparous women but significantly different for multiparous women. A decade ago 48% of women in private and public hospitals were considered low risk. This compares with 43% in our study a decade later. In NSW, the caesarean section rate has increased from 19% in 1998 to 30.2% in 2009.16 The caesarean section rate is much higher for the private sector and has been accompanied by an even sharper rise over the past decade as seen in our research. MacDorman et al 23 suggested that the rapid increase in the caesarean section rate from 1996 onward in the USA reflected two current trends: an increase in the primary caesarean section rate and a steep decline in vaginal birth after a primary caesarean section. A similar pattern is seen in Australia with increasing primary caesarean and repeat caesarean section rates.1 It is commonly asserted that the rise in the caesarean section rate is due to changing demographics, such as older women, obese women and more complex medical profiles, which are a reality today in many resource rich nations. However, in our study, which only included low-risk women, the rise in caesarean section was independent of these factors. Other studies and government reports have also shown the dramatic rise in caesarean section independent of these risk factors.1 23 24

Most concerning in this study was the fact that a low-risk primiparous woman has a 20% lower chance of having a normal birth (44%) if she gives birth in a private hospital under obstetric care in NSW than in a public hospital (64%). The implications for women and babies in terms of short-term and long-term morbidity3 4 25 are not insignificant. The cost of high intervention rates in childbirth is also significant to society. Tracy and Tracy8 studied the incremental cost increase to the public purse as interventions were introduced in the labour and birth process. They found that the relative cost of birth increased by up to 50% for low-risk primiparous women and up to 36% for low-risk multiparous women as labour interventions accumulated. An epidural was associated with a sharp increase in cost of up to 32% for some primiparous low-risk women, and up to 36% for some multiparous low-risk women. Private obstetric care increased the overall relative cost by 9% for primiparous low-risk women and 4% for multiparous low-risk women.8

The levelling-out of the caesarean section rate from 2006 onwards may reflect the changes in government policy, research and international trends.5 7 26 However, over the past decade while obstetric interventions have steadily increased among low-risk women receiving public hospital care by more than 5%, they have increased by over 10% among women receiving private obstetric care in private hospitals. This disparity between the two services in health (private and public) is concerning, especially when much of the care in the private sector is funded from the public purse and more importantly the taxpayer. While women choosing private healthcare are also taxpayers and hence entitled to subsidisation this subsidy needs to be associated with a requirement for accountability to the funder.

Conclusion

The continual rise in obstetric intervention for low-risk women in Australia is concerning in terms of morbidity for women and cost to the public purse. The fact that these procedures which were initially life-saving are now so commonplace and do not appear to be associated with improved perinatal death rates demands close review. Low-risk primiparous women giving birth in private hospitals have more chance of a surgical birth than a normal vaginal birth and this phenomenon has increased markedly in the past decade with the gap between the public and private sector growing wider. Australia strives to provide a health system which offers equal access and equity to its population. The findings of this study suggest that a two-tier system exists in Australia without any obvious benefit for women and babies and a level of medical over servicing which is difficult to defend within a system that is bound by a finite health dollar.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HD led the study and wrote the paper. ST helped in constructing the study design and writing the paper. MT helped in constructing the study design. AB helped in writing the paper. CB gave biostatistical support and helped in writing the paper. CT helped with study design, analysis and writing of the paper.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: New South Wales Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee, Protocol No.2010/12/291.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional data are available.

References

- 1.Li Z, McNally L, Hilder L, et al. Australia's mother and babies 2009. In: AIHW , ed. Sydney: AIHW National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit, 2011. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/health_glance-2011-en/04/09/index.html;jsessionid=2639olt7qcgp9.delta?contentType=&itemId=/content/chapter/health_glance-2011-37-en&containerItemId=/content/serial/19991312&accessItemIds=/content/book/health_glance-2011-en&mimeType=text/html (Accessed 1 June 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 2.OECD Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Health Data 2009. (accessed 16 Nov 2011) 2009

- 3.Clark EAS, Silver RM. Long-term maternal morbidity associated with repeat caesarean delivery. Am J Obst Gynecol 2011;S2(December). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyde MJ, Mostyn A, Modi N, et al. The health implications of birth by caesarean section. Biol Rev 2011;doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UK Maternity Care Working Party Making normal birth a reality. http://www.appg-maternity.org.uk MCWPDf, ed. London: NCT/RCM/RCOG, 2007. (Accessed 1 June 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S.Department of Health and Human Services Healthy people 2020 Washington, DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.NSW Health Towards normal birth in NSW. NSW Health, 2010. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/pd/2010/pdf/PD2010_045.pdf (Accessed 1 June 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tracy SK, Tracy M. Costing the cascade: estimating the cost of increased obstetric intervention in childbirth using population data. Br J Obst Gynaecol 2003;110:717–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen VM, O'Connell CM, Farrell SA, et al. Economic implications of method of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193:192–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts CL, Tracy S, Peat B. Rates of obstetric intervention among private and public patients in Australia: population based descriptive study. Br Med J 2000;312:137–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Read A, Prendiville W, Dawes V, et al. Cesarean section and operative vaginal delivery in low-risk primiparous women. Western Aust Am J Public Health 1994;84:37–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le R, Carayol M, Zeitlin J, et al. Level of perinatal care of the maternity unit and rate of cesarean in low-risk nulliparas. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1269–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tracy SK, Tracy M, et al. Costing the cascade: estimating the cost of increased obstetric intervention in childbirth using population data. BJOG 2003;110:717–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tracy SK, Sullivan ES, Tracy MB, et al. Admission of term infants to neonatal intensive care: A population based study. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care 2007;34(4):301–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NSW Health NSW Mothers and Babies 2009. Sydney: NSW Health [Google Scholar]

- 16.NSW Health NSW mothers and babies 2009. Sydney: NSW Health [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLachlan HL, Forster DA, Davey MA, et al. Effects of continuty of care by a primary midwife (caseload midwifery) on caesarean section rates in women of low obstetric risk: the COSMOS randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2012;doi: 10.111/j.1471-0528.2012.03446.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leitch CR, Walker JJ. The rise in caesarean section rate: the same indications but a lower threshold. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:621–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor L, Travis S, Pym M, et al. How useful are hospital morbidity data for monitoring conditions occurring in the perinatal period? Aust N Z J Obst Gynaecol 2005;45:36–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts C, Bell J, Ford J, et al. Monitoring the quality of maternity care: how well are labour and delivery events reported in population health data? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2008;23: 144–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thornton C, Makris A, Ogle R, et al. Generic obstetric database systems are unreliable for reporting the Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obst Gynaecol 2004;44:505–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkelstein A, Fiebelkorn IC, Wang G. National medical Spending attributable to overweight and obesity: How much and who's paying Health Affairs. 2003; Project HOPE-The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc.:219–26 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.MacDorman M, Menacker F, Declercq E. Caesarean birth in the United States: epidemiology, trends and outcomes. Clin Perinatol 2008;35:293–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Declercq E, Menacker F, MacDorman MF. Maternal risk profiles and the primary cesarean rate in the United States, 1991–2002. Am J Public Health 2006;96:869–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silver R M, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al. , Network ftNIoCHaHDM-FMU Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat caesarean deliveries. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1226–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.NHS Wales All Wales Clinical Pathway for Normal Birth. http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/page.cfm?orgid=327&pid=5786 (accessed 7 Feb 2012) 2006

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.