Abstract

Objective

Assess the current BCG vaccination policies and delivery pathways for immunisation in Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) in England since the 2005 change in recommendations.

Design

A survey of key informants across PCTs using a standardised, structured questionnaire.

Setting

152 PCTs in England.

Results

Complete questionnaires were returned from 127 (84%) PCTs. Sixteen (27%) PCTs reported universal infant vaccination and 111 (73%) had selective infant vaccination. Selective vaccination outside infancy was also reported from 94 (74%) PCTs. PCTs with selective infant policy most frequently vaccinated on postnatal wards (51/102, 50%), whereas PCTs with universal infant vaccination most frequently vaccinated in community clinics (9/13, 69%; p=0.011). To identify and flag up eligible infants in PCTs with targeted infant immunisation, those who mostly vaccinate on postnatal wards depend on midwives and maternity records, whereas those who vaccinate primarily in the community rely more often on various healthcare professionals.

Conclusions

Targeted infant vaccination has been implemented in most PCTs across the UK. PCTs with selective infant vaccination provide BCG vaccine via a greater variety of healthcare professionals than those with universal infant vaccination policies. Data on vaccine coverage would help evaluate the effectiveness of delivery. Interruptions of delivery noted here emphasise the importance of not just an agreed, standardised, local pathway, but also a named person in charge.

Article summary.

Article focus

An important control measure, especially in the era of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, is BCG vaccination. In 2005 the UK moved from a school-aged universal BCG vaccination policy to a targeted policy towards children at high risk. To date, it is unknown as to how this vaccination policy is operating at the local level (via Primary Care Trusts)

Key messages

Targeted infant vaccination has been implemented in most areas in England, but delivery pathways are complex and appear to vary between Primary Care Trusts.

Areas with selective infant vaccination provide BCG vaccine via a larger number of healthcare providers than those with universal infant vaccination policies.

These findings emphasise the need to standardise local pathways, to allocate clear responsibilities and to monitor vaccination coverage.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a public health problem in England. After a century of consistent decline in the incidence and annual infection risk, the incidence of TB has been rising since the late 1980s.1 TB is concentrated within certain groups of the population (including migrants from high-prevalence countries, prisoners, homeless persons and other marginal populations) and in urban areas.2

Since the 1950s, immunisation with the BCG vaccine, which has been shown to be highly effective in the UK population,3 has been a part of TB control efforts in England. The routine policy had been primarily to administer the BCG vaccine to all tuberculin-negative schoolchildren aged 10–14 years. In some areas BCG was given during infancy and it was recommended that it should also be given to ‘children of immigrants in whose communities there is a high incidence of TB’, among other high-risk groups.4 In 2005, this policy was replaced by a targeted immunisation programme directed at children with high risk of TB exposure.

The change in policy came after several years of discussion in the independent government advisory committee, the Joint Committee of Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI). In the 1990s, it was estimated that due to the low TB incidence, universal school-age vaccination was no longer cost-effective.5 Universal BCG vaccination, however, remained policy largely because the incidence was rising slowly and health authorities were unsure about the impact that the emerging HIV epidemic could have on TB epidemiology.5 6 In 2005, after the HIV epidemic had stabilised and the UK had already fulfilled the criteria of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (IUATLD) to stop routine immunisation (which recommends different policies for different levels of TB, based on economic appraisals and the balance between the benefits and risks of BCG vaccination),7 the JCVI recommended stopping universal school-age vaccination and replacing it with a targeted infant vaccination programme.5

As part of this targeted infant programme, it is agreed that universal vaccination is the most effective way to reach all eligible children in areas of the country with TB incidence ≥40 per 100 000 person-years (pyrs). In areas with TB incidence <40 per 100 000 pyrs, a selective approach is recommended to immunise only infants at high risk, that is, if their parents or grandparents originate from a country with an incidence ≥40 per 100 000 pyrs, if travelling to a high-incidence country for 3 or more months or when in contact with a TB case. In addition, children of any age at high risk of TB should be vaccinated at suitable opportunities.8

In view of possible organisational changes in the NHS and given the current TB epidemiology in the country, we considered it important and timely to assess the BCG vaccine policy and the main vaccine delivery pathways across the commissioning bodies for community and hospital care (Primary Care Trusts, PCTs) in England.

Methods

A standardised, mostly closed-ended structured questionnaire was designed (available from the authors). The questionnaire covered the vaccination policy inside and outside infancy, eligibility criteria and their documentation, delivery pathways and constraints to service delivery. The questionnaire was piloted in four London PCTs.

In November 2010, we contacted all 152 PCTs in England. Immunisation leads and other staffs involved in TB control and BCG vaccination implementation were electronically mailed a copy of the questionnaire and a web-link to an internet equivalent created using the survey engine SurveyMonkey. As delivery of BCG vaccine involves a chain of activities and responsibilities, respondents were asked to gather information from other key informants as needed. A reminder was sent after 4 weeks. After an additional 4 weeks, we contacted non-respondent PCTs by telephone to gather the information required.

At completion of the active data collection, as an additional data check, between August 2011 and September 2011, we searched PCTs’ websites and related NHS sources for publicly available documents on their current BCG vaccination policy. We assessed the agreement between the information on these publicly available documents and the data collected from the survey. We compared distribution frequencies using a χ2 test or Fisher's exact test where appropriate. For each variable, we only included observations for which data were available.

Results

Between November 2010 and March 2011, 123 questionnaires representing 129/152 PCTs (85%) were returned: 72 (59%) as electronic documents and 51 (41%) via the internet survey. No difference in TB notification rates was found between responding and non-responding PCTs (data not presented). We found publically available current BCG policy documents for 114 (88%) of the 129 PCTs. Two (2%) PCTs were excluded from subsequent analysis because their BCG policy could not be determined from the responses. Sixteen (13%) PCTs reported universal infant vaccination and 111 (87%) selective infant vaccination. The agreement with publically available BCG policy documents was high, with only three (2%) PCTs reporting a policy that was different from the information in these documents. Responses from these three PCTs to more detailed questions in the questionnaire were consistent with a selective infant vaccination at that time.

Three PCTs reported changing their policy between 2006 and 2011; one PCT followed the national recommendation and changed from targeted infant vaccination to universal infant vaccination as TB incidence exceeded 40 per 100 000 pyrs; one PCT changed to universal infant vaccination, although their TB incidence was <40 per 100 000 pyrs but justified doing so because of a borderline TB rate, high TB rates in neighbouring areas and high population mobility; one PCT had a universal infant vaccination programme prior to 2006, although their TB incidence was below the threshold, and changed to targeted infant vaccination.9

Some PCTs reported vaccination policies that did not reflect the JCVI recommendations. Six PCTs reported targeted infant vaccination despite having a 3-year average TB incidence ≥40 per 100 000.9 Documents obtained from the websites, however, of three of these PCTs, state that they implement universal infant BCG vaccination. Six of the 16 PCTs reporting universal vaccination had 3-year average TB incidence ≤40 per 100 000.9 They were all in or close to major conurbations.

Vaccination during infancy

PCTs with a selective infant BCG vaccination policy administer BCG via a wider range of healthcare providers than PCTs with universal infant BCG vaccination (table 1). PCTs with selective policy most frequently offer vaccination on postnatal wards (51/102, 50%) but also vaccinate in community (24/102, 24%) and hospital clinics (27/102, 26%); PCTs with universal policy more frequently offer vaccination in community clinics (9/13, 69%) and less frequently on postnatal wards (4/13, 31%, p=0.011).

Table 1.

Place where BCG is primarily administered and systems reported to document BCG vaccination in 127 Primary Care Trusts with infant vaccination policy

| Selective infant vaccination |

Universal infant vaccination |

|

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Place of primary BCG administration | N=102* | N=13** |

| Postnatal ward | 51 (50) | 4 (31) |

| At home | 0 | 0 |

| At community clinic | 24 (23) | 9 (69) |

| At chest clinic | 17 (17) | 0 |

| At hospital paediatric clinic | 10 (10) | 0 |

| Systems in use for BCG documentation | N=107*** | N=16 |

| Antenatal/maternity records | 43 (40) | 5 (31) |

| Birth notification records | 15 (14) | 2 (12) |

| Paper log books held by midwives | 6 (6) | 1 (6) |

| Child health information system | 100 (93) | 14 (88) |

| School health records | 27 (25) | 5 (31) |

| GP | 50 (46) | 3 (19) |

| Red Book | 103 (96) | 16 (100) |

| Discharge letters | 37 (35) | 2 (12) |

GP, general practitioner.

*Nine, **three and ***four missing values for those variables.

All PCTs that vaccinate primarily on postnatal wards do so during the infants’ first month of life, whereas only 13/37 (35%) PCTs that mainly vaccinate in community clinics do so in the infants’ first month of life (p<0.001).

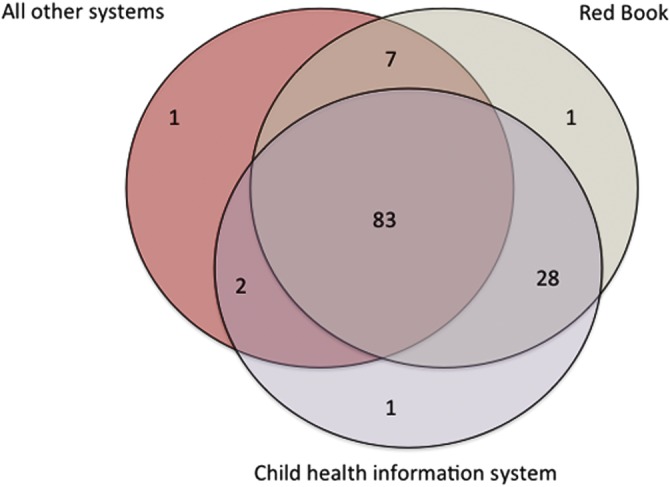

BCG vaccination receipt in infancy is documented in various ways across PCTs, and this did not depend on the vaccination policy (table 1). It is most consistently documented in the Red Book (119/123, 97%) and in the Child Health Information Systems (114/123, 93%). It is also noted in other registers and notes (table 1), but always in combination with either or both of the former two (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Principal systems used to document BCG vaccination and their combinations in Primary Care Trusts with infant vaccination policy (N=123).

Selective infant vaccination

In the 111 PCTs with selective infant vaccination, 71% reported routinely assessing eligibility for BCG. They all offer BCG vaccination to children with parents or grand parents born in countries with TB incidence ≥40 per 100 000 pyrs (table 2). Six PCTs reported that travel to a high-incidence country for 3 or more months is not an eligibility criterion; and two PCTs reported that contact with a TB case is not a selection criterion either.

Table 2.

Selection criteria employed to decide eligibility for BCG vaccination in 111 Primary Care Trusts with a targeted infant vaccination policy

| n (%)* | |

|---|---|

| Infant of parents born in country with incidence >40 per 100000 | 107 (100) |

| Contact with TB | 93 (87) |

| Prolonged travel | 94 (88) |

| Parental request | 14 (13) |

| Insecure accommodation | 13 (12) |

| Socially deprived | 2 (2) |

| Asylum seeker/refugees | 2 (2) |

*Four observations with missing data.

TB, tuberculosis.

Two main BCG delivery pathways were apparent from the information on identification and primary place of immunisation, but with considerable overlap. Where midwives are primarily responsible for identifying eligible infants, they are more frequently vaccinated on postnatal wards (37/56, 66%) than when eligibility is flagged by general practitioners (GPs), health visitors (HVs) or paediatricians (12/44, 27%; p<0.001). Conversely, in PCTs in which eligible infants are primarily flagged up by GPs, HVs or paediatricians, they are more frequently vaccinated in community clinics (32/44, 73%) than when midwives identify them (19/56, 34%; p<0.001). In line with these delivery pathways, when infants are identified by midwives or vaccinated on postnatal wards, their eligibility is most frequently flagged up in maternity records, whereas when infants are identified by GPs, HVs or paediatricians or when they are vaccinated in community clinics, various systems are used with no clear preference (table 3).

Table 3.

Systems in use to flag up infants’ eligibility for BCG vaccination stratified by main responsible for identification in 111 Primary Care Trusts with targeted infant vaccination

| Systems used to flag up eligibility | Identification primarily by midwives* |

Identification primarily by GP, HV or paediatrician* |

|---|---|---|

| N=51 | N=38 | |

| Maternity records | 43 (84%) | 14 (37%) |

| Baby's hospital notes | 28 (55%) | 18 (47%) |

| Red Book | 25 (49%) | 22 (56%) |

| Birth notification records | 10 (20%) | 6 (16%) |

| Child health information system | 10 (20%) | 6 (16%) |

*Twenty-two observations with missing data.

GP, general practitioner; HV, health visitor.

Vaccination outside of infancy

Vaccination outside infancy was reported in 94/127 (74%) PCTs. In 14/94 (14%) PCTs vaccination outside of infancy is offered to preschool children only, in 9/94 (9%) to schoolchildren only and in the remaining PCTs to both groups. HVs are most frequently involved in identifying eligible preschool children (51/85, 51%). GPs alone were mentioned by 3/85 (4%) PCTs but 33/85 (36%) PCTs reported that both GPs and HV identify eligible preschool children. A similar pattern was seen for the identification of school children: school nurses alone identify eligible school children in 56/80 (70%) PCTs, GPs alone in 9/80 (11%) PCTs and in 15/80 (19%) PCTs both school nurses and GPs identify school children.

All PCTs offering vaccination outside infancy reported assessing previous BCG immunisation in eligible children using at least one of the criteria recommended by the Green Book. Sixty-four of 94 (68%) PCTs use a combination of reliable parental recall, documentary evidence and presence of a scar as evidence of previous BCG vaccination. Seventy of 94 (18%) PCTs use the combination of a BCG scar and reliable recall; whereas 13/94 (14%) consider only one criterion as sufficient evidence.

Logistic constraints hindering BCG administration

Of all PCTs, 26/127 (20%) reported periods between 2005 and 2010 during which they could not administer BCG due to logistic constraints. The most frequent reasons are vaccine supply shortage and lack of trained health workers (including access to training) to administer the vaccine. One PCT reported various episodes where no BCG could be administered as a result of a pending business case over who was to carry out BCG vaccination when the previously appointed community paediatrician retired. A similar problem was reported in a different PCT reporting unclear responsibilities after the adult respiratory department stopped seeing paediatric patients. In one PCT, BCG could not be administered over a 2-year period due to the absence of funding agreements and was only reintroduced after a school outbreak.

Discussion

Six years after its introduction, the 2005 recommendation for BCG vaccination has been implemented in the vast majority of England PCTs. All surveyed PCTs have an infant vaccination policy in place, but a quarter of these PCTs do not report offering vaccination outside infancy. Selective infant vaccination mostly takes place on the postnatal ward and during the first month of life whereas universal infant vaccination mainly happens in community clinics and after the first month of life. In PCTs with a selective infant vaccination policy, this survey found greater variation in the organisation of BCG vaccine delivery.

We were unable to gather information from 15% of the PCTs. However, TB notification rates between responding and non-responding PCTs were similar, suggesting results presented are not likely to be biased.

Since the JCVI issued their recommendations in 2005, there has been an ongoing discussion about how to define areas of high TB incidence in the context of the policy.10–12 Universal infant vaccination is, for operational reasons, recommended in PCTs where the TB incidence is ≥40 per 100 000 pyrs, as it is agreed that this is the most efficient way to reach all infants at high risk of TB in such areas. Nevertheless, the cut-off incidence for targeted infant vaccination is debated as children in PCTs with an incidence <40 per 100 000 pyrs can still be at high risk of TB.13

In this survey, six PCTs in or close to urban areas reported vaccinating all infants, although their PCT-specific incidence is <40 per 100 000 pyrs. This could indicate that some PCTs in urban areas are considering regional incidence to inform their policies, rather than PCT-specific incidence. Nevertheless, it remains uncertain if this strategy ensures that the maximum number of eligible children are being immunised, and if it is more cost-effective than a PCT-specific informed targeted vaccination policy. Further analysis of the economic efficiency of regional BCG vaccination is required.

Surveys of BCG vaccination policies and practices in England and Wales in 1982 and 1992 indicated considerable variations across health districts.14 15 In 1992, 15 of the 186 health districts in England had already stopped their routine school immunisation programme; 148 offered BCG to selected groups of neonates and five districts routinely gave BCG to all their neonates.15 Today, variation in local BCG vaccination policies is lower but the organisation of BCG delivery remains highly variable. We find that PCTs commission a wide range of healthcare providers to deliver the vaccine. This heterogeneity across PCTs also demands a high level of organisation between PCTs if services such as maternity care straddle PCT borders. Hospitals may not be co-terminous with PCTs and hence infants from PCTs with different policies and practices can be born in the same hospital. In this light, it is of concern that many PCTs do not have service-level agreements to organise BCG administration either within the PCT or across boundaries.4 This and the complexity of managing a localised service could also explain why some PCTs were unable to deliver BCG during periods where service providers changed.

The commissioning of BCG may become more complex if it becomes the responsibility of Clinical Commissioning Consortia. In its current form, the suggested changes to the NHS structure could lead to consortia responsible for overlapping geographical areas. If services are not commissioned across boundaries and responsibilities are not clearly assigned, the current heterogeneity in policies and practices could increase and seriously compromise the targeted infant vaccination. Infant hepatitis B vaccination is another selective programme, being given to infants of mothers screened antenatally and found to be positive for hepatitis B carriage. It works best when there is an identified person in each area, who is responsible for coordinating the programme.16 This model should be considered for the BCG programme.

While the structural organisation of the NHS poses challenges for the 2005 recommendations, the implementation of a targeted vaccination policy is, in its self, demanding.17 Hence, it is vital to monitor the implementation to assure high vaccination coverage. Good data on BCG immunisation coverage are complicated to assemble in PCTs with targeted infant vaccination where the denominator is unclear. Data from audits, however, show that vaccination coverage in areas with targeted infant vaccination can be low18 and that even in PCTs with high coverage, it can vary greatly between maternity units19 and ethnic groups.20 We find that a wide range of healthcare professionals are involved in the identification of eligible children. It is therefore conceivable that infants are not identified due to unclear responsibilities. In addition, our findings suggest that some health professionals involved in the BCG vaccination programme might be unfamiliar with recommended eligibility criteria; this could contribute to low coverage rates.21 A standardised pathway to identify eligible infants, with clear responsibilities and roles and regular training of staffs involved, could contribute to high vaccination coverage in PCTs with selective vaccination policy.22 23

In addition to the correct identification of infants at risk, assuring that the vaccine is administered is another challenge of a targeted vaccination policy.17 22 Half of the PCTs vaccinate on postnatal wards—a vaccine delivery pathway associated with high vaccination coverage in local audits.22–24 The other half, however, vaccinate in a community setting or clinics which in this survey was associated with vaccination at an older age. The different delivery pathways probably reflect local circumstances. Immunising newborns in postnatal wards may be more optimal in conditions in which the workload is manageable at that level, with either a relatively lower number of eligible newborns or a sufficient number of skilled personnel to administer BCG. Vaccinating in the community might be more effective in areas with higher numbers of eligible newborn (especially if universal BCG vaccination) and limited number of trained staffs to administer the vaccine in postnatal wards. However, the latter could mean a higher risk of attrition as parents may not return their children to immunisation appointments, as reported in previous audits.23 25 A study in South London found that parents would be more interested if the vaccine was accessible on a ‘drop-in’ basis from community clinics18 in such areas.

Another aspect that might affect efficient delivery is that the most commonly used systems for documentation of BCG receipt are often not the systems used to flag up eligibility. Aligning the systems used to identify eligible children with the system used to document BCG vaccination could be an effective way to ensure that identified infants receive the vaccine and a means to estimate coverage.24 Also, BCG vaccination was not delivered with other routine infant vaccinations possibly because of the need for specific training for an intradermal vaccination. The addition of BCG vaccination to offer of other routine infant vaccinations in specific regions could be another way of ensuring coverage of those at risk.

The 2005 BCG policy for the UK also recommends vaccinating previously unvaccinated children who are at high risk of TB. Despite the policy, a quarter of all PCTs do not report vaccinating outside infancy. Although the absence of vaccination outside infancy may conserve resources in areas with low levels of migration, some PCTs in urban centres with presumably high levels of migration do not report vaccinating outside infancy. This suggests that greater efforts are needed to strengthen targeted BCG vaccination outside infancy.

In conclusion, a targeted infant BCG vaccination has been implemented in most PCTs across England, either as part of postnatal hospital care or a community vaccination programme separate from other childhood vaccinations via a number of locally agreed healthcare professionals. Information to assess coverage would be useful to monitor successful provision of an effective measure to prevent childhood TB.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all who took part in the survey. We also thank Ms Joanne White from the HPA-Colindale for providing the list of immunisation leads in PCTs, as well as useful discussions on BCG vaccine delivery in the UK. PM and PND thank NIHR (HTA) for funding. IA is funded through an NIHR Senior Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Contributors: PM, IA, LR had the initial idea for the study and designed the survey instrument with DE. VE and DP helped to test the instrument. DP collected responses, analysed and interpreted them and did the initial draft of the manuscript. PND helped with data collection, analysis, and with DP and PM interpreted the results and edited the manuscript. JW contributed to the interpretation of results. All authors contributed to the final manuscript. All authors had access to all the data in the study and held final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding: This study was conducted as part of the NIHR (HTA) funded project 08/17/01 “Observational study to estimate the changes in the efficacy of BCG with time since vaccination.”

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work other than mentioned in acknowledgements; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Health Protection Agency Tuberculosis in the UK: annual report on tuberculosis surveillance in the UK 2010. London: HPA, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abubakar I, Lipman M, Anderson C, et al. Tuberculosis in the UK—time to regain control. BMJ 2011;343:d4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MRC Tuberculosis Vaccines Clinical Trials Committee. B.C.G. and vole bacillus vaccines in the prevention of tuberculosis in adolescents; first (progress) report to the Medical Research Council by their Tuberculosis Vaccines Clinical Trials Committee. BMJ 1956;1:413–27 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Standing Medical Advisory Committee for the Central Health Services Council, The Secretary of State for Social Services, The Secretary of State for Scotland et al. Immunisation against infectious disease. London: Department of Health and Social Security; 1972 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisaton. Minutes of the JCVI BCG Subgroup, Thursday 7 April 2005, 2005

- 6.Fine P. Stopping routine vaccination for tuberculosis in schools. BMJ 2005;331:647–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Criteria for discontinuation of vaccination programmes using Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) in countries with a low prevalence of tuberculosis. A statement of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Tuberc Lung Dis 1994;75:179–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. Tuberculosis. In: Salisbury D, Ramsay M, Noakes K. eds. Immunisation against infectious diseases. Norwich: The Stationery Office, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health Protection Agency. Geography—TB data by UK primary care organisation. 2010. http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1287147465528 (cited 2011 September).

- 10.Ahmed AB, King K. Change in BCG vaccination policy—unresolved issues of implementation. BMJ 2005;331:647–816179677 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health. Operational note to profession Changes to the BCG vaccination programme in England. 2005

- 12.Ruwende JE, Sanchez-Padilla E, Maguire H, et al. Recent trends in tuberculosis in children in London. J Public Health (Oxf) 2011;33:175–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eriksen J, Chow JY, Mellis V, et al. Protective effect of BCG vaccination in a nursery outbreak in 2009: time to reconsider the vaccination threshold? Thorax 2010;65:1067–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller CL, Morris J, Pollock TM. PHLS inquiry into current BCG vaccination policy. BMJ 1984;288:564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph CA, Watson JM, Fern KJ. BCG immunisation in England and Wales: a survey of policy and practice in schoolchildren and neonates. BMJ 1992;305:495–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE public health guidance 21: reducing differences in the uptake of immunisations (including targeted vaccination) among children and young people aged under 19 years. 2009

- 17.Smith CP, Parle M, Morris DJ. Implementation of government recommendations for immunising infants at risk of hepatitis B. BMJ 1994;309:1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tseng E, Nesbitt A, O'Sullivan D. Audit of the implementation of selective neonatal BCG immunisation in south east London. Commun Dis Rep CDR Rev 1997;7:R165–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etuwewe O, Wood A, Lyon A. Delivering a selective neonatal BCG vaccination programme in a multi-ethnic community: an audit of the neonatal BCG immunisation programme in Birmingham and Solihull. Commun Dis Public Health 2004;7:172–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srinivasan R, Menon L, Stevens P, et al. Ethnic differences in selective neonatal BCG immunisation: white British children miss out. Thorax 2006;61:247–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon M, Roberts H, Odeka E. Knowledge and attitudes of parents and professionals to neonatal BCG vaccination in light of recent UK policy changes: a questionnaire study. BMC Infect Dis 2007;7:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed S, Hicks NR, Stanwell-Smith R. Policy and practice—an audit of neonatal BCG immunization in Avon. J Public Health Med 1992;14:389–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill J, Scott J. Improving the uptake of selective neonatal BCG immunisation. Commun Dis Public Health 1998;1:281–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chappel D, Fernandes V. Improving the coverage of neonatal BCG vaccination. J Public Health Med 1996;18:308–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakshi D, Sharief N. Selective neonatal BCG vaccination. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:1207–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.