Abstract

Objective

To investigate the possible association between total daily iron intake during pregnancy, haemoglobin in early pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in women at increased risk of GDM.

Design

A prospective cohort study (based on a cluster-randomised controlled trial, where the intervention and the usual care groups were combined).

Setting

Primary healthcare maternity clinics in 14 municipalities in south-western Finland.

Participants

399 Pregnant women who were at increased risk of GDM participated in a GDM prevention trial and were followed throughout pregnancy.

Main outcome measurements

The main outcome was GDM diagnosed with oral glucose tolerance test at 26–28 weeks’ gestation or based on a diagnosis recorded in the Finnish Medical Birth registry. Data on iron intake was collected using a 181-item food frequency questionnaire and separate questions for supplement use at 26–28 weeks’ gestation.

Results

GDM was diagnosed in 72 women (18.1%) in the study population. The OR for total iron intake as a continuous variable was 1.006 (95% CI 1.000 to 1.011; p=0.038) after adjustment for body mass index, age, diabetes in first-degree or second-degree relatives, GDM or macrosomia in earlier pregnancy, total energy intake, dietary fibre, saturated fatty acids and total gestational weight gain. Women in the highest fifth of total daily iron intake had an adjusted OR of 1.66 (95% CI 0.84 to 3.30; p=0.15) for GDM. After excluding participants with low haemoglobin levels (≤120 g/l) already in early pregnancy the adjusted OR was 2.35 (95% CI 1.13 to 4.92; p=0.023).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that high iron intake during pregnancy increases the risk of GDM especially in women who are not anaemic in early pregnancy and who are at increased risk of GDM. These findings suggest that routine iron supplementation should be reconsidered in this risk group of women.

Keywords: Gestational Diabetes, Iron Intake, Iron Supplementation, Pregnancy, Haemoglobin

Article summary.

Article focus

The objective of this study was to investigate the possible association between total daily iron intake from both food and supplements during pregnancy, haemoglobin levels in early pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes in women at increased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Key messages

Our results suggest that high iron intake during pregnancy increases the risk of GDM especially in women who are not anaemic in the beginning of the pregnancy and who are at increased risk of GDM.

Our findings suggest that routine iron supplementation should be reconsidered in this risk group of women.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Unlike most of the previous studies we had detailed information of iron intake from both food and supplements.

We had information of baseline OGTT and could therefore exclude women with undiagnosed prepregnancy diabetes. Additionally Finnish Medical Birth Registry could be utilised to cover those GDM cases that were undiagnosed in the 26–28 weeks’ OGTT.

We also had information of haemoglobin measurements of the study population during pregnancy although measured by nurses.

All of our data was collected prospectively.

The participation rate in the original trial was high (88% in both the intervention and the usual care groups) improving the generalisability of the results to other women with risk factors for GDM.

Iron intake was assessed at a certain point in time, thus it does not cover the intake during the whole pregnancy.

We could not assess iron absorption.

The haemoglobin levels were screened at the maternity clinics using finger-stick samples, which may not be an optimal measurement tool.

Haemoglobin measurements were missing for 28 women at 8–12 weeks’ gestation and we used the measurement at 16–18 weeks’ gestation for those women.

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a disturbance in glucose metabolism, which is diagnosed during pregnancy and affects 1–14% of pregnancies in different populations.1 The incidence of gestational diabetes has been increasing the last 20 years.2 Risk factors for GDM include higher maternal body mass index (BMI), higher age and family history of diabetes.3 Approximately half of the GDM cases can be explained by overweight.4 GDM causes short-term and long-term risks to both the mother and the child. The most common result of GDM is newborn macrosomia, which increases several adverse outcomes during delivery such as shoulder dystocia, perineal lacerations, blood loss and increased caesarean birth.5 GDM also increases the risk of glucose metabolism disorders and type 2 diabetes in later life of the mother and the newborn.6 7

High iron load and disorders of iron metabolism have been associated with an increased risk of disturbances in glucose metabolism.8–10 In hereditary hemochromatosis iron accumulation in the body leads to diabetes in 30–60% of patients.11 Also in animal models iron has been shown to induce diabetes.12 Iron binding medication is effective in preventing diabetes in iron overload conditions.13 Frequent blood donation has been shown to result in improvement in glucose metabolism even in healthy people.14 Higher iron stores have been found in gestational diabetes patients measured most commonly by serum ferritin.15–17 High haemoglobin level in early pregnancy has been reported to be an independent risk factor for GDM18 and lower haemoglobin levels and anaemia during pregnancy have been shown to result in lower risk of GDM.19 A large proportion of women, up to 78% in Finland,20 use supplemental iron during pregnancy even with good haemoglobin levels and thus it is an important matter to investigate the possible adverse effects of iron. High iron intake could be especially risky for women with already good iron stores.

Studies of total iron intake and the risk of GDM are scarce: only Bowers et al21 have investigated pre-pregnancy total iron intake in relation to the risk of GDM. Other studies have investigated iron intake either from food or supplements only and have thus failed to report the effect of total iron intake.22 23 Only one placebo controlled clinical trial has been conducted on supplemental iron and the risk of GDM.24 To our knowledge there are no published studies of total iron intake during pregnancy, haemoglobin and the risk of GDM. The objective of this study was to investigate the possible association between total daily iron intake from both food and supplements during pregnancy, haemoglobin levels in early pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes in women at increased risk of GDM.

Material and methdos

The data of this study were originally collected as a part of a larger gestational diabetes prevention trial, which is described in more detail elsewhere.25 The effects of the intervention on GDM and newborns birth weight have been reported elsewhere.26 This cluster-randomised trial was carried out in 14 municipalities in Pirkanmaa region in south-western Finland in 2007–2009. The municipalities were randomised in pairs into intervention and usual care municipalities.

The inclusion criteria for the trial were to have at least one of the following risk factors: BMI ≥25 kg/m2; age ≥40 years; GDM, glucose intolerance or newborn's macrosomia (≥4500 g) in any earlier pregnancy or type 1 or 2 diabetes in first-degree or second-degree relatives. Women were excluded from the trial if they had an abnormal measurement in the baseline (8–12 weeks’ gestation) glucose tolerance test (fasting blood glucose ≥5.3 mmol/l, >10.0 mmol/l at 1 h or >8.6 mmol/l at 2 h); pre-pregnancy diabetes (type 1 or 2); age <18 years; no Finnish language skills; multiple pregnancy; restrictions from physical activity; substance abuse or psychiatric illness. The trial was approved by the ethical committee of Pirkanmaa Hospital District and written informed consent was provided by the participants.

A total of 2271 women were screened for the study and of them 726 were preliminary eligible to participate in the study.26 Of these women 640 (88.2%) gave an informed consent to participate in the trial. At the baseline (8–12 weeks’ gestation) oral glucose tolerance test 174 women had an abnormal result and were thus excluded. Furthermore 38 women had a miscarriage and 29 were lost to follow-up. Finally, 399 participants were included in the analyses (219 in the intervention group and 180 in the usual care group).

The intervention group participated in individual counselling on weight gain, physical activity and diet on five antenatal visits in primary healthcare maternity clinics. The objectives of the counselling were to guide the participants in monitoring their weight gain, increasing or maintaining their leisure time physical activity and achieving a healthy diet fulfilling the national recommendations. The effects of intensified dietary counselling on food habits and the intake of energy, energy-yielding nutrients, fibre, selected fatty acids and cholesterol have been reported elsewhere.27 The counselling was not aiming to influence in iron intake. In this study the intervention and usual care groups were combined and these groups had no differences in the incidence of GDM or in iron intake.

Background information of the participants was gathered with a baseline questionnaire at the first prenatal visit (8–12 weeks’ gestation). Information of pre-pregnancy BMI (weight self-reported and height measured at 8–12 weeks’ visit) and haemoglobin were abstracted from maternity cards. In this study we used information of haemoglobin measurements from early pregnancy (weeks 8–12, or 16–18 for those with missing values for 8–12 weeks) to determine the status of body iron stores in the beginning of pregnancy and before the physiological decrease in haemoglobin levels. The participants were considered to have good haemoglobin levels if they had a haemoglobin measurement of over 120 g/l according to the lower limit for normal haemoglobin in non-pregnant women.28 The limit for normal haemoglobin in pregnant women (110 g/l) was not used because of low frequency of cases with haemoglobin level under 110 g/l in early pregnancy (n=7). All women underwent a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test at 26–28 weeks’ gestation. The criterion for gestational diabetes diagnosis was to have at least one abnormal value: fasting glucose after an overnight fast ≥5.3 mmol/l, blood glucose >10.0 mmol/l 1 h after or >8.6 mmol/l 2 h after consuming 75 g of glucose. To cover all possible cases information of gestational diabetes was abstracted from the Finnish Medical Birth Register.

Information on diet and supplement use was obtained by a validated 181-item food frequency questionnaire29 although the validity of the supplement data was not assessed in the study by Erkkola et al. The participants completed the questionnaire at 8–12 weeks’ gestation and again at 26–28 and 36–37 weeks’ gestation. In the 8–12 weeks’ questionnaire the participants were asked about their dietary habits during 1 month before beginning of the pregnancy and in 26–28 and 36–37 weeks’ questionnaires the participants were asked about their dietary habits during the previous month. The completed questionnaires were checked by a nutritionist and those with more than 10 missing values in the frequency data were completed after consulting the participant on the phone. In the food frequency questionnaire the dietary habits were assessed by detailed questions of frequency of use (per day, week, month or not at all) and the portion sizes of specific food items. The participants were also asked to report their supplement use: brand name of the supplement, dosage and frequency of use (per day, week or month). The gathered data were then entered into a food database using a software program of the National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland, and coded to daily food record form. Nutrient intakes were calculated by using the 10th release (updated in 2009) of the Finnish Food Composition Database Fineli (http://www.fineli.fi) and in-house software of the National Institute for Health and Welfare. In this study information of dietary habits and supplement use at 26–28 weeks of gestation was used to get the best estimation of iron intake and the intake of energy, macronutrients and dietary fibre during pregnancy and before the onset of GDM.

Statistical methods

The study population was categorised into five equal groups according to their total daily iron intake. To better see the differences between women in the highest fifth of total iron intake and the other women, we combined the three groups in the middle (20%, 60% and 20%). The groups were tested for possible differences in risk factors, dietary intake and other background characteristics using χ2 test, Kruskal-Wallis test or One-way analysis of variance. The incidence of GDM was then investigated between the iron intake groups and the differences were tested statistically using χ2 or Fisher exact tests. Haemoglobin was considered as a potential effect modifier. Women were divided into two groups according to their haemoglobin level in early pregnancy: >120 or ≤120 g/l.

Logistic regression was used to assess the OR for gestational diabetes. The dependent variable in the regression model was GDM (yes/no). In the first model iron intake was assessed as a continuous variable. In the second model the highest fifth of total iron intake (intake ≥110 mg) was compared to the rest of the study population (iron intake under 110 mg). The models were adjusted for BMI, age, intake of energy, saturated fatty acids and dietary fibre and total gestational weight gain (all as continuous) as well as diabetes in first-degree or second-degree relatives and GDM or macrosomia in earlier pregnancy (both as categorical). Both models were executed separately for all women and for women with haemoglobin levels over 120 g/l in early pregnancy (8–12 or 16–18 weeks’ gestation).

We also added interaction terms for iron intake and haemoglobin and for iron intake and BMI to the model but they were not statistically significant and therefore are not presented here. In sensitivity analyses, we examined the association between the total iron intake and the risk of GDM using alternative cut-off points for categorising participants based on their iron intake (15%, 70% and 15%; 25%, 50% and 25% and 30%, 40% and 30%) and the same statistical tests as described above. All analyses were performed with SPSS statistics (V.19).

Results

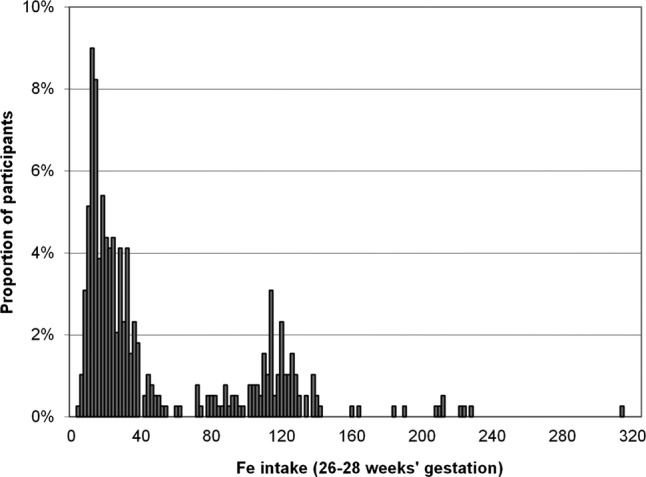

On the basis of the questionnaire completed at 26–28 weeks’ gestation, the mean daily iron intake from food was 14.4 mg (SD 4.3; median 13.9 mg) among the study population. In the study group 65.7% of women used supplemental iron and the median of supplemental intake was 27 mg. The most used dosages for iron supplementation were 10, 20 and 100 mg of elemental iron (Fe2+). The median for total iron intake was 27.1 mg (IQR 15.5–89.3 mg; figure 1). Iron intake from food was similar in non-users and users of supplemental iron: users of supplemental iron had a mean daily intake of 14.5 mg (SD 4.5) and nonusers 14.3 mg (SD 3.9). The mean haemoglobin level of the study population in the beginning of pregnancy was 134 g/l (SD 11; minimum 107 and maximum 169 g/l).

Figure 1.

Total iron intake in mid pregnancy (26–28 weeks’ gestation).

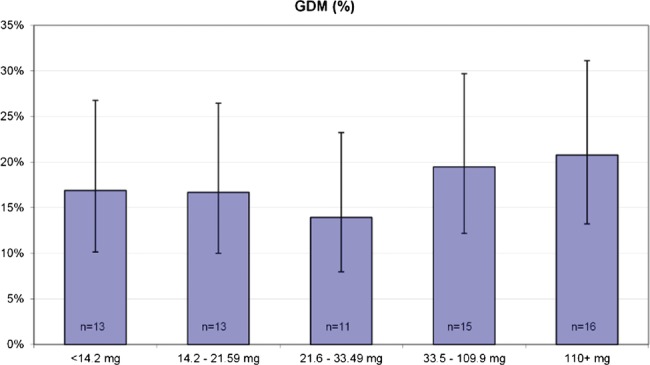

The oral glucose tolerance test at 26–28 weeks’ gestation was abnormal in 14% of the study population (n=56, missing value for three women). Furthermore 16 women received a gestational diabetes diagnosis during their pregnancy. Figure 2 shows the incidence of GDM in fifths of total iron intake. There was a tendency for a higher incidence of GDM in the highest fifth of total iron intake.

Figure 2.

Incidence of GDM (%) in fifths of total iron intake.

Between the iron intake groups (20%, 60% and 20%) there were no significant differences in terms of proportion of primigravida, age, diabetes in first-degree or second-degree relatives or GDM or macrosomia in earlier pregnancy (table 1). Women in the highest iron intake group had a slightly lower mean BMI as compared with other women (p=0.05). Haemoglobin levels in early pregnancy differed between the groups as excepted (p<0.001). With regard to differences in dietary intake, women in the lowest iron intake group had lower total energy and dietary fibre intakes than the other women whereas women in the highest iron intake group had higher intake of saturated fatty acids than the other women. Total gestational weight gain did not differ between the iron intake groups. Table 2 shows the incidence of GDM in the three iron intake groups. The incidence was higher in the highest iron intake group (20.8%) compared to the other two groups (16.7% in both) but the difference was not statistically significant (p0.70). When including women with haemoglobin levels >120 g/l in early pregnancy (n=321, mean Hb 135, SD 9), the difference between the groups was even larger but still not statistically significant (p=0.11).

Table 1.

Background characteristics of iron intake groups (20%, 60% and 20%), means (SD) or frequencies (%)

| 20% | 60% | 20% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <14.2 mg/day (n=78) | 14.2–109.9 mg/day (n=233) | 110.0+ mg/day (n=78) | p Value | |

| Total Fe intake (mg/day) | 11.6 (2.0) | 36.0 (25.1) | 136.2 (36.5) | – |

| Primigravida | 34 (43.6) | 96 (41.2) | 43 (55.1) | 0.099* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 (4.4) | 26.5 (4.7) | 25.2 (4.3) | 0.050† |

| Age (years) | 29.3 (5.1) | 29.8 (4.4) | 29.6 (5.4) | 0.70† |

| Diabetes in first-degree or second-degree relatives | 44 (57.1) | 127 (54.5) | 48 (61.5) | 0.55* |

| GDM or macrosomia in previous pregnancy | 14 (18.2) | 33 (14.2) | 10 (12.8) | 0.60* |

| Hb (8–12 weeks‡) (g/l) | 135.4 (9.6) | 134.0 (10.9) | 127.0 (10.0) | <0.001§ |

| Total energy intake (MJ/day) | 8.3 (1.5) | 10.1 (2.6) | 9.9 (2.7) | <0.001† |

| Protein (E%)¶ | 18.0 (2.3) | 18.0 (2.2) | 18.1 (2.2) | 0.81§ |

| Carbohydrates (E%) | 48.0 (4.4) | 48.6 (4.8) | 47.3 (4.9) | 0.071§ |

| Saccharose (E%) | 10.7 (3.4) | 10.6 (3.4) | 10.8 (2.6) | 0.54‡ |

| Dietary fibre (g/day) | 20.7 (6.0) | 26.8 (9.2) | 25.8 (8.6) | <0.001§ |

| Total fat (E%) | 32.9 (4.0) | 32.3 (4.4) | 33.4 (4.1) | 0.099§ |

| Saturated fatty acids (E%) | 12.7 (2.0) | 12.5 (2.7) | 13.3 (2.5) | 0.015‡ |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids (E%) | 12.1 (1.9) | 11.9 (1.8) | 12.2 (1.7) | 0.57§ |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids (E%) | 5.2 (1.0) | 5.0 (0.9) | 5.0 (0.9) | 0.85§ |

| Total gestational weight gain (kg) | 14.1 (5.5) | 13.9 (5.3) | 14.5 (5.4) | 0.81§ |

*χ2 test.

†Kruskal-Wallis test.

‡16–18 for those with missing values at 8–12 weeks (n=28), missing: Hb n=5, 20 and 6, respectively.

§One-way ANOVA.

¶Percentage of total energy intake. Data on dietary intake was collected by the food frequency questionnaire completed at 26–28 weeks’ gestation.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; Hb, haemoglobin.

Table 2.

GDM frequency in iron intake groups (20%, 60% and 20%)

| N | GDM, frequency (%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All women | |||

| (20%) <14.2 mg/day | 78 | 13 (16.7) | 0.70* |

| (60%) 14.2–109.9 mg/day | 233 | 39 (16.7) | |

| (20%) 110.0+ mg/day | 78 | 16 (20.8) | |

| Hb (8–12 weeks†) >120 g/l | |||

| (20%) <14.2 mg/day | 69 | 13 (18.8) | 0.11* |

| (60%) 14.2–109.9 mg/day | 194 | 30 (15.5) | |

| (20%) 110.0+ mg/day | 58 | 16 (27.6) | |

| Hb (8–12 weeks†) ≤120 g/l | |||

| (20%) <14.2 mg/day | 3 | 0 | 0.45‡ |

| (60%) 14.2–109.9 mg/day | 21 | 3 (14.3) | |

| (20%) 110.0+ mg/day | 12 | 0 | |

*χ2 test.

†16–18 for those with missing values at 8–12 weeks (n=28).

‡Fisher's exact test.

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; Hb, haemoglobin.

The logistic regression model shows that after adjustment for potential risk factors and background characteristics total iron intake was significantly and positively associated with gestational diabetes mellitus (table 3). When iron intake was used as a continuous variable the OR was 1.006 (p=0.038) for all women and 1.009 (p=0.006) for those with haemoglobin levels over 120 g/l. In the second model, the OR for GDM was 1.66 (95% CI 0.84 to 3.30, p=0.15) for the highest fifth of iron intake among all women. After excluding women with low haemoglobin levels (≤120 g/l) in early pregnancy the OR was 2.35 (95% CI 1.13 to 4.92, p=0.023).

Table 3.

Incidence of GDM, unadjusted and adjusted ORs (95% CI) for iron intake at 26–28 weeks’ gestation as a continuous and a categorical variable separately for all women and for women with haemoglobin >120 g/l

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | pValue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe intake as a continuous variable | ||||

| All women | ||||

| Total Fe intake (mg/day) | 1.004 (0.999 to 1.008) | 0.16 | 1.006 (1.000 to 1.011) | 0.038 |

| BMI | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.16) | 0.006 | ||

| Age | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.07) | 0.78 | ||

| Diabetes in first-degree or second-degree relatives | 0.87 (0.49 to 1.55) | 0.63 | ||

| GDM or macrosomia in a previous pregnancy | 1.77 (0.86 to 3.64) | 0.12 | ||

| Total energy intake (MJ/day) | 0.89 (0.74 to 1.06) | 0.19 | ||

| Dietary fibre (g/day) | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.08) | 0.43 | ||

| Saturated fatty acids (E%)† | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.09) | 0.48 | ||

| Total gestational weight gain | 0.94 (0.89 to 1.00) | 0.039 | ||

| Women with Hb (8–12 weeks’ gestation‡) >120 g/l | ||||

| Total Fe intake (mg/day) | 1.007 (1.001 to 1.012) | 0.013 | 1.009 (1.003 to 1.015) | 0.006 |

| BMI | 1.07 (1.00 to 1.15) | 0.042 | ||

| Age | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.08) | 0.78 | ||

| Diabetes in first-degree or second-degree relatives | 0.73 (0.39 to 1.36) | 0.32 | ||

| GDM or macrosomia in a previous pregnancy | 1.78 (0.80 to 3.95) | 0.16 | ||

| Total energy intake (MJ/day) | 0.83 (0.68 to 1.01) | 0.066 | ||

| Dietary fibre (g/day) | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.10) | 0.14 | ||

| Saturated fatty acids (E%)† | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.13) | 0.75 | ||

| Total gestational weight gain | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) | 0.028 | ||

| Fe intake as a categorical variable | ||||

| All women | ||||

| Total Fe intake (the highest 20% vs the lowest 80%) | 1.31 (0.70 to 2.44) | 0.40 | 1.66 (0.84 to 3.30) | 0.15 |

| BMI | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.15) | 0.010 | ||

| Age | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.07) | 0.77 | ||

| Diabetes in first-degree or second-degree relatives | 0.84 (0.47 to 1.50) | 0.55 | ||

| GDM or macrosomia in a previous pregnancy | 1.65 (0.93 to 3.37) | 0.17 | ||

| Total energy intake (MJ/day) | 0.89 (0.80 to 1.06) | 0.19 | ||

| Dietary fibre (g/day) | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.08) | 0.37 | ||

| Saturated fatty acids (E%)† | 0.97 (0.85 to 1.10) | 0.59 | ||

| Total gestational weight gain | 0.94 (0.89 to 0.99) | 0.029 | ||

| Women with Hb (8–12 weeks’ gestation‡) >120 g/l | ||||

| Total Fe intake (the highest 20% vs the lowest 80%) | 1.95 (1.005 to 3.78) | 0.048 | 2.35 (1.13 to 4.92) | 0.023 |

| BMI | 1.07 (1.00 to 1.14) | 0.054 | ||

| Age | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.08) | 0.76 | ||

| Diabetes in first-degree or second-degree relatives | 0.70 (0.38 to 1.31) | 0.27 | ||

| GDM or macrosomia in a previous pregnancy | 1.60 (0.73 to 3.53) | 0.24 | ||

| Total energy intake (MJ/day) | 0.83 (0.69 to 1.02) | 0.071 | ||

| Dietary fibre (g/day) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11) | 0.10 | ||

| Saturated fatty acids (E%)† | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.15) | 0.92 | ||

| Total gestational weight gain | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.99) | 0.017 | ||

*Adjusted for other variables in the model (total Fe intake, BMI, age, diabetes in first-degree or second-degree relatives, GDM or macrosomia in a previous pregnancy, total energy intake, dietary fibre, saturated fatty acids and total gestational weight gain).

†Percentage of total energy intake.

‡16–18 weeks’ gestation for those with missing values at 8–12 weeks’ gestation (n=28).

BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; Hb, haemoglobin.

In sensitivity analyses the ORs were higher when 15% of women with the highest iron intake were compared to the rest 85% of women. The ORs were lower when 25% or 30% of women with highest intake were compared to the rest 75% and 70% of women, respectively (results not shown).

Discussion

In this study we investigated the possible association between total daily iron intake during pregnancy, haemoglobin in early pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes. To our knowledge there are no similar studies published previously. We discovered that there was a tendency for a higher incidence of GDM in the highest fifth of total iron intake. High iron intake increased the risk of GDM especially for those women who had good haemoglobin levels in early pregnancy: we discovered a twofold OR for GDM for women in the highest fifth of iron intake with a haemoglobin level of over 120 g/l in early pregnancy.

Our study has several strengths. First unlike most of the previous studies we had detailed information of iron intake from both food and supplements. Second, we had information on baseline oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and could therefore exclude women with undiagnosed pre-pregnancy diabetes. Additionally, Finnish Medical Birth Registry could be utilised to cover those GDM cases that were undiagnosed in the 26–28 weeks’ OGTT. We also had information of haemoglobin measurements of the study population during pregnancy although measured by nurses. All of our data was collected prospectively. The participation rate in the original trial was high (88% in both the intervention and the usual care groups) improving the generalisability of the results to other women with risk factors for GDM.

A limitation of this kind of study is that estimating iron intake during pregnancy can be challenging because dietary habits and use of supplements can vary a lot during pregnancy due to nausea and other changes in well-being. Iron intake was assessed at a certain point in time (at 26–28 weeks’ gestation covering the previous month), thus it does not cover the intake during the whole pregnancy. In our study, we decided to use information of iron intake in mid-pregnancy to get the best estimation on iron intake during pregnancy and before the onset of GDM. We did not use information of iron intake abstracted in the beginning of pregnancy because it covered only dietary habits and supplement use during 1 month before the pregnancy when use of supplemental iron is rare. However, our information on iron intake covers only 1 month in the mid-pregnancy. Additionally we could not assess iron absorption, for example with blood measurements, which also can vary a lot depending on body iron status and the contents of meals.

There are also limitations concerning the haemoglobin measurements used in our study. In the maternity clinics haemoglobin levels are usually screened with a capillary haemoglobin measurement using finger-stick samples. This method has been demonstrated to be reliable in determining haemoglobin values but it is however susceptible to handling errors30 and therefore there can be variation in the test results. Additionally, we had a lot of missing values in haemoglobin measurements and thus we decided to use the haemoglobin measurement at 16–18 weeks’ gestation for those with missing values at weeks 8–12 (n=28). Although measurements at weeks 16–18 do not present the haemoglobin levels at early pregnancy our objective was to analyse separately women who were not anaemic and thus including women who had a haemoglobin level of over 120 g/l still at weeks 16–18 would help us not to underestimate the proportion of women who were not anaemic in the beginning of the pregnancy. However, for these reasons our results with respect to haemoglobin measurements should be considered with caution and further studies with reliable and comprehensive haemoglobin measurements are warranted to confirm our results.

In a somewhat similar study Bo et al22 discovered that women who used supplemental iron during mid-pregnancy had a twofold to threefold risk of GDM. They however had no information of dietary intake of iron or haemoglobin levels or other measurements of iron stores. Their findings are however in line with our results which suggest that dietary intake could play a relatively small part in the association whereas high supplemental iron intake could be responsible for most of the increase in GDM risk. Somewhat different results have been reported recently by Bowers et al21 and Qiu et al.23 Bowers et al21 investigated dietary and supplemental iron intake during 1 year before pregnancy utilising the material from the Nurses Health study. They observed no significant effect of total, non-heme or supplemental iron intake on the risk of GDM. It can be argued though that usually iron supplementation outside of pregnancy is rare and concerns mainly those who are anaemic. However, they did find a significant and positive association between haeme iron intake and GDM. Similarly Qiu et al23 demonstrated an association between haeme iron intake during the time before conception and in early pregnancy and the risk of GDM. To our knowledge only one placebo-controlled clinical trial has been conducted to investigate the association between iron supplementation and GDM.24 This study did not observe any association. However, it can be argued that the intake of supplemental iron was quite low in this study because of only about 50% compliance to a daily supplement of 60 mg of elemental iron.

Iron is a highly reactive component with a possibility to participate in harmful reactions.31 The human body can excrete iron with very limited mechanisms and thus iron intake is highly regulated according to body iron needs.32 Iron could interfere with glucose metabolism in several ways. For example, following mechanisms have been proposed: Iron decreases insulin extraction and metabolism in the liver, which leads to peripheral hyperinsulinaemia.33 Iron overload results in oxidative stress in pancreatic β-cells, which leads to destruction of the pancreatic islets and thus decreases insulin secretion.34 The exact mechanisms, which link iron to diabetes are still unsolved. However, the association can be argued to be biologically plausible.

Accumulating body of evidence supports the hypothesis of excess iron as a risk factor for glucose metabolism disorders such as gestational diabetes. Iron deficiency anaemia has been shown to reduce the incidence of GDM.19 Respectively high haemoglobin level (>130 g/l) in early pregnancy has been demonstrated to be an independent risk factor for GDM.18 It seems that iron can affect glucose metabolism even with no overt iron overload. Women diagnosed with GDM have been observed to have increased iron stores compared to women without GDM.15 17 However, many of these studies have been cross-sectional and it has been criticised that higher serum ferritin levels could in fact reflect inflammation in the body and could be rather a result than a cause for diabetes.16

In summary it seems that high iron intake might be a factor, which increases the risk of GDM especially in women with already good iron stores. Use of iron supplements during pregnancy is common even in women with good haemoglobin levels. Our results suggest that routine use of iron supplements should be reconsidered in non-anaemic women with risk factors for GDM. To confirm the hypothesis there is need for a large prospective study—ideally a randomised controlled trial—with reliable and comprehensive information on iron intake from food and supplements during pregnancy accompanied with serum measurements to determine the level of body iron stores.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Jatta Puhkala is acknowledged for checking and coding the dietary data. We also sincerely thank all the nurses of the participating maternity clinics for their invaluable work in implementing the study protocol and the pregnant women who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: AH, TIK and RL designed and conducted research; AH and JR performed statistical analyses; AH drafted the paper and revised it based on the comments from the other authors. SMV and SA were responsible for the FFQ method and for dietary calculations. TIK and RL have the primary responsibility for final content. All authors read, commented and approved the final manuscript. RL is the guarantor.

Funding: (Finnish) Diabetes Research Fund, Competitive Research Funding of the Tampere University Hospital, Academy of Finland, Ministry of Education and Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The ethical committee of Pirkanmaa Hospital District, Tampere, Finland.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional unpublished data from the study may be available and it can be enquired with the authors.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2012;35(Suppl 1):S64–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrara A. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a public health perspective. Diabetes Care 2007;30(Suppl 2):S141–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King H. Epidemiology of glucose intolerance and gestational diabetes in women of childbearing age. Diabetes Care 1998;21(Suppl 2):B9–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SY, England L, Wilson HG, et al. Percentage of gestational diabetes mellitus attributable to overweight and obesity. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1047–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stotland NE, Caughey AB, Breed EM, et al. Risk factors and obstetric complications associated with macrosomia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2004;87:220–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee AJ, Hiscock RJ, Wein P, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus: clinical predictors and long-term risk of developing type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study using survival analysis. Diabetes Care 2007;30:878–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clausen TD, Mathiesen ER, Hansen T, et al. Overweight and the metabolic syndrome in adult offspring of women with diet-treated gestational diabetes mellitus or type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:2464–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuomainen TP, Nyyssonen K, Salonen R, et al. Body iron stores are associated with serum insulin and blood glucose concentrations. Population study in 1,013 eastern Finnish men. Diabetes Care 1997;20:426–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford ES, Cogswell ME. Diabetes and serum ferritin concentration among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1978–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang R, Manson JE, Meigs JB, et al. Body iron stores in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in apparently healthy women. JAMA 2004;291:711–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powell LW, Yapp TR. Hemochromatosis. Clin Liver Dis 2000;4:211–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Awai M, Narasaki M, Yamanoi Y, et al. Induction of diabetes in animals by parenteral administration of ferric nitrilotriacetate. Am J Pathol 1979;95:663–73 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brittenham GM, Griffith PM, Nienhuis AW, et al. Efficacy of deferoxamine in preventing complications of iron overload in patients with thalassemia major. N Engl J Med 1994;331:567–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Real JM, Lopez-Bermejo A, Ricart W. Iron stores, blood donation, and insulin sensitivity and secretion. Clin Chem 2005;51:1201–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lao TT, Chan PL, Tam KF. Gestational diabetes mellitus in the last trimester—a feature of maternal iron excess?. Diabet Med 2001;18:218–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Scholl TO, Stein TP. Association of elevated serum ferritin levels and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnant women: the Camden study. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1077–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afkhami-Ardekani M, Rashidi M. Iron status in women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications 2009;23:194–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lao TT, Chan LY, Tam KF, et al. Maternal hemoglobin and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in Chinese women. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:807–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lao TT, Ho LF. Impact of iron deficiency anemia on prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2004;27:650–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arkkola T, Uusitalo U, Pietikainen M, et al. Dietary intake and use of dietary supplements in relation to demographic variables among pregnant Finnish women. Br J Nutr 2006;96:913–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowers K, Yeung E, Williams MA, et al. A prospective study of prepregnancy dietary iron intake and risk for gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1557–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bo S, Menato G, Villois P, et al. Iron supplementation and gestational diabetes in midpregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:158.e1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu C, Zhang C, Gelaye B, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus in relation to maternal dietary heme iron and nonheme iron intake. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1564–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan KK, Chan BC, Lam KF, et al. Iron supplement in pregnancy and development of gestational diabetes—a randomised placebo-controlled trial. BJOG 2009;116:789–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luoto RM, Kinnunen TI, Aittasalo M, et al. Prevention of gestational diabetes: design of a cluster-randomized controlled trial and one-year follow-up. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luoto R, Kinnunen TI, Aittasalo M, et al. Primary prevention of gestational diabetes mellitus and large-for-gestational-age newborns by lifestyle counseling: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinnunen TI, Puhkala J, Raitanen J, et al. Effects of dietary counseling on food habits and dietary intake of Finnish pregnant women at increased risk for gestational diabetes—a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Matern Child Nutr. Published Online First 27 June 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00426.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.World Health Organization Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention and control. A guide for programme managers. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001; WHO/NHD/01.3 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erkkola M, Karppinen M, Javanainen J, et al. Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire for pregnant Finnish women. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:466–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ziemann M, Lizardo B, Geusendam G, et al. Reliability of capillary hemoglobin screening under routine conditions. Transfusion 2011;51:2714–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papanikolaou G, Pantopoulos K. Iron metabolism and toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2005;202:199–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrews NC. Disorders of iron metabolism. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1986–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandez-Real JM, Lopez-Bermejo A, Ricart W. Cross-talk between iron metabolism and diabetes. Diabetes 2002;51:2348–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooksey RC, Jouihan HA, Ajioka RS, et al. Oxidative stress, beta-cell apoptosis, and decreased insulin secretory capacity in mouse models of hemochromatosis. Endocrinology 2004;145:5305–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.