Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether a polymorphism in the Fcγ receptor type IIIA (FCGR3A-F158V), influencing immunoglobulin G binding affinity, relates to the therapeutic efficacy of rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients.

Design

Observational cohort study.

Setting

Three university hospital rheumatology units in Sweden.

Participants

Patients with established RA (n=177; 145 females and 32 males) who started rituximab (Mabthera) as part of routine care.

Primary outcome measures

Response to rituximab therapy in relation to FCGR3A genotype, including stratification for sex.

Results

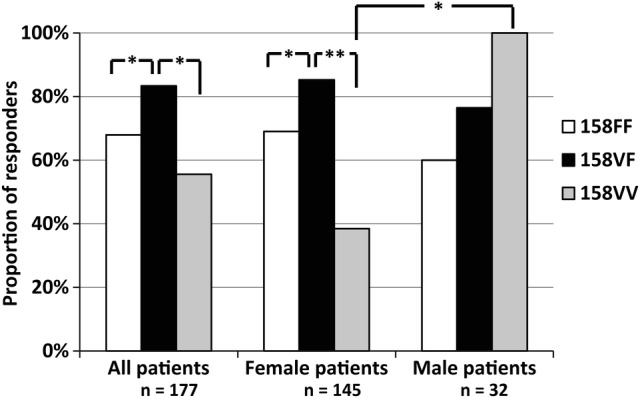

The frequency of responders differed significantly across FCGR3A genotypes (p=0.017 in a 3×2 contingency table). Heterozygous patients showed the highest response rate at 83%, as compared with patients carrying 158FF (68%) or 158VV (56%) (p=0.028 and 0.016, respectively). Among 158VV patients, response rates differed between male and female patients (p=0.036), but not among 158FF or 158VF patients (p=0.72 and 0.46, respectively).

Conclusions

Therapeutic efficacy of rituximab in RA patients is influenced by FCGR3A genotype, with the highest response rates found among heterozygous patients. This may suggest that different rituximab mechanisms of action in RA are optimally balanced in FCGR3A-158VF patients. Similar to the previously described associations with RA susceptibility and disease course, the impact of 158VV on rituximab response may be influenced by sex.

Keywords: Rheumatology, Immunology, Therapeutics

Article Summary.

Article focus

A functional polymorphism in the gene encoding Fcγ receptor type IIIA (FCGR3A) influences the outcome of B cell-depleting therapy with rituximab in malignancies.

Although rituximab is frequently used for the therapy of severe RA, studies on RA patients have been lacking.

We wished to determine if FCGR3A-F158V genotype associates with rituximab efficacy in RA.

Key messages

FCGR3A heterozygous patients experienced significantly higher response rates than 158FF and 158VV patients.

The results are discordant to a similar recently published study based on 111 RA patients.

There are indications of a sex-specific effect of the 158VV genotype, as have been previously described regarding RA susceptibility and disease course.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Although limited by the small numbers of males and 158VV patients, this is until now the largest published study on FCGR3A and rituximab in RA patients.

Differences could have been attenuated by the ‘real-life’ approach, that is, that therapy was not administered by a standardised scheme, and the time to evaluation varied between patients.

Introduction

The growing arsenal of biological agents available in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) pharmacotherapy increases the demand for predictors of therapeutic responses and/or side effects. Human Fcγ receptors mediate effector functions of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies and may modulate the therapeutic efficacy of all biological substances containing IgG-Fc parts. Hence, a functional single-nucleotide polymorphism in FCGR3A (FCGR3A-F158V, rs396991), influencing IgG binding affinity to the activating Fcγ receptor type IIIA (FcγRIIIA),1 has been associated with the therapeutic efficacy of rituximab (RTX), that is, an anti-CD20 B cell-depleting IgG1 monoclonal antibody, in B cell malignancies.2 3 RTX-coated B cells may be eliminated by several mechanisms; complement-dependent cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cytotoxocity (ADCC) by natural killer (NK) cells, and/or phagocytosis by FcγR-bearing cells. Although the relevance in humans has not been established, mice lacking proper complement or NK-cell functions are equally well B cell depleted as native animals, thus pointing towards a major role of FcγR-bearing macrophages.4 It has been convincingly shown that RTX binds with higher affinity to 158V in an allele-dose-dependent manner and that ADCC by NK cells are affected accordingly.5 Data regarding FCGR3A genotype and RTX efficacy in RA has been lacking until recently, when Ruyssen-Witrand et al6 reported an association between carriage of the high-affinity binding valine (V) allele of FCGR3A and higher response rates to RTX.

Numerous case–control studies have been performed with regard to FCGR3A-F158V and RA susceptibility. Although initial studies showed remarkably discordant results, subsequent investigations have shown an association between homozygosity of the high-affinity allele (158VV) and an increased risk of RA in Europeans.7–10 In studies presenting data stratified for sex, the increased risk conferred by the 158VV genotype only attributes to the male population.7 10 In line with this, male patients with early RA carrying 158V have a more severe disease course whereas, intriguingly, in female patients the opposite is seen.7 The biological basis for this sex difference is yet to be elucidated, but it has been shown that oestrogen influences both FcγRIIIA expression and FcγRIIIA-mediated release of tumour necrosis factor and IL-1β from monocytic cells.11

The current study was conducted to explore the influence of FCGR3A genotype on RTX efficacy in RA patients.

Patients and methods

Patients with established RA (n=177; 145 females and 32 males) who started RTX (Mabthera) as part of routine care at three rheumatology clinics in Sweden (Karolinska University Hospital, Solna; Linköping University Hospital, Linköping; and Umeå University Hospital, Umeå, Sweden) were included in the study. Baseline characteristics and concurrent medication are shown in table 1. The therapeutic response was assessed by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) response criteria after 3–6 months.12 DNA was extracted from whole blood by standard techniques and FCGR3A-F158V was genotyped by a commercially available TaqMan assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA, ID C_25815666_10). Validation of the TaqMan results was performed in 30 samples (10 of each genotype), yielding 100% concordance with a previously described direct sequencing assay specific for FCGR3A.7

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 177 RA patients according to FCGR3A genotype

| 158VV (n=18) | 158VF (n=78) | 158FF (n=81) | Total (n=177) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) disease duration, years | 11 (6) | 15 (10) | 14 (12) | 14 (11) |

| Females, n (%) | 13 (72) | 61 (78) | 71 (88) | 145 (82) |

| Rheumatoid factor positive, n (%) | 12 (67) | 62 (81) | 63 (78) | 137 (78) |

| Baseline DAS28, mean (SD) | 5.2 (1.0) | 5.5 (1.1) | 5.5 (1.2) | 5.5 (1.1) |

| Concurrent DMARD therapy, n (%) | 15 (83) | 48 (62) | 59 (73) | 122 (69) |

| Oral glucocorticoid therapy, n (%)* | 13 (72) | 55 (72)# | 48 (64)## | 116 (69)### |

| Number of previous TNF inhibitors, mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.1) |

*Data available on: #76/78 patients, ##75/81 patients, ###169/177 patients.

DMARD, disease modifying antirheumatic drugs; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Statistical analysis

Response rates were compared by χ2 test across FCGR3A genotypes, and by Fisher's exact test between sexes. Baseline characteristics were tested by χ2 test for categorical variables and by one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. Two-sided p values <0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS V.19.

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained from all patients according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the regional ethics committees in Linköping, Stockholm and Umeå.

Results

Overall, 130 patients (73%) achieved a moderate or good EULAR response, whereas 47 (27%) were non-responders. The distribution of FCGR3A genotypes was 81 (46%) 158FF, 78 (44%) 158VF and 18 (10%) 158VV, which is in agreement with previous findings in Swedish RA populations,7 13 and in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p>0.95). The proportion of EULAR good responders did not differ significantly across FCGR3A genotypes (21%, 26% and 28% for 158FF, 158VF and 158VV, respectively). However, the proportion of good and moderate responders together, compared to non-responders, was significantly different across FCGR3A genotypes (p=0.017 in a 3×2 contingency table), where heterozygous patients showed the highest response rate (65 of 78 patients, 83%), as compared to 55/81 (68%) patients carrying 158FF (OR 2.36, 95% CI 1.04 to 5.41, p=0.028), and 10/18 (56%) 158VV patients (OR 4.0, 95% CI 1.16 to 13.9, p=0.016; figure 1). The frequency of responders was not significantly different between 158FF and 158VV (OR 1.69, 95% CI 0.53 to 5.37, p=0.4). Baseline characteristics (table 1) revealed no significant differences across FCGR3A genotypes. Experiencing a therapeutic response was more common among rheumatoid factor (RF)-positive cases as compared with RF-negative cases (OR 2.38, 1.05 to 5.39, p=0.038), and in the RF-positive group, response rates remained significantly different across FCGR3A genotype (p=0.004), but did not reach statistical significance among RF-negative cases (p=0.056). After stratifying for sex, response rates among female patients remained different in 158VF as compared with 158FF (p=0.047) and 158VV (p=0.001), but this was not seen in the smaller group of males (p>0.4; figure 1). Furthermore, among 158VV patients, men had significantly higher response rates than women (100% vs 39%, respectively, p=0.036), while therapeutic response among 158FF or 158VF patients did not differ between men and women (p=0.72 and 0.46, respectively). Absolute changes in DAS28 in relation to FCGR3A yielded similar results as for categorical EULAR responses (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Proportion of rituximab responders in relation to FCGR3A genotype in RA patients. Significant differences are indicated as *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Discussion

Although an influence of FCGR3A-F158V on RTX efficacy was in line with our hypothesis, the lack of a clear allele-dose effect points towards a more complex role of FCGR3A in RTX therapy of RA than anticipated. On the basis of previous reports of increased RTX-induced ADCC,5 more pronounced peripheral B cell depletion,14 better clinical outcomes in B cell malignancies,2 3 we expected any difference to appear in favour of the 158VV genotype. Also, a recent study on 111 RA patients described an association between the 158V allele and response to RTX.6 Our study is, to our knowledge, the largest on this topic to date, and we surprisingly found a significantly larger proportion of responders among FCGR3A-F158V heterozygous patients, a finding to which there is no immediate explanation from previous experimental work. Regarding the in vivo situation little is known, however, as the mechanisms whereby RTX reduces signs and symptoms of RA remain incompletely understood. The initial view that the disease-modifying action of RTX depends on depletion of B cells and the eventual disappearance of pathogenic autoantibodies is contradicted by several observations. For instance, although circulating autoantibodies may indeed decline, they seldom disappear,15 and both non-circulating B cells and autoantibody production in the synovium are clearly less affected by RTX than their circulating counterparts.16 Other proposals for RTX mode of action in RA include the immune complex decoy hypothesis, suggesting that RTX-opsonised B cells keep disease-promoting FcγR-expressing phagocytic cells busy eliminating B cells instead of perpetuating synovial inflammation.17 In this context, one would expect that the more pronounced activation of FCGR3A-158VV macrophages would render them less prone to divert from the immune complex-driven rheumatoid inflammation in the synovium, and hence corresponding to a worse therapeutic outcome in 158VV patients as seen in the current study. Alternatively, FCGR3A-158VV individuals could, as compared to FCGR3A-158FF, handle RTX-opsonised B cells more efficiently and may thereby, to a greater extent and more rapidly, return from this drug-induced diversion. Our finding of a significantly higher response rate among heterozygous patients could possibly point towards several mechanisms being involved in RTX action and that, in RA, these are most optimally balanced in individuals with the intermediate binding variant of FcγRIIIA, that is, FCGR3A-158VF.

A previous study on RA patients reported that the proportion of responders among 158VF patients was significantly higher compared to 158FF cases, but that the proportion of responders among 158VV were similar to 158VF, albeit failing to reach statistical significance when compared with 158VF or 158FF.6 Merging the response data from the two studies yields a significantly better response rate among 158VF as compared to 158FF, (OR 2.82, 95% CI 1.44 to 5.56, p=0.001), whereas the 158VV group does not differ significantly from neither 158VF (OR 0.41, 0.15 to 1.15, p=0.067) nor 158FF (OR 1.17, 95% CI 0.46 to 2.99, p=0.83).

Shortcomings of the current study include the fact that therapeutic response was assessed with up to 3 months variation between patients. However, a separate analysis of patients with response assessed at 6 months (n=108) yielded similar results, making a major impact of follow-up time-point unlikely. Our finding that 158VV patients less frequently experience response to RTX is discordant with the findings of Ruyssen-Witrand et al, and the limited number of 158VV patients (in both studies) adds uncertainty to firm conclusions regarding this particular genotype. Further, the relatively limited number of male patients calls for cautious interpretation of the findings regarding sex differences. Still, we believe that the 158VV sex difference is of interest, as no tendencies towards sex differences were found among 158FF and 158VF patients, despite being substantially larger groups. Also, there are previously described sex-dependent associations of 158VV in RA.7 10 The FCGR locus is subject to copy number variation (CNV), and in the current study CNV of FCGR3A was not investigated. However, the functional consequences of FCGR3A CNV remains unknown, and a previous study showed that only 5% of Swedish individuals carry ≠2 copies of FCGR3A.18

On the basis of currently available data, we conclude that FCGR3A-F158V heterozygosity is associated with a better response to RTX in RA patients as compared with homozygosity of the low-affinity F allele. Data regarding patients carrying two high-affinity alleles, 158VV, remains inconclusive and needs to be resolved before FCGR3A-F158V may become clinically relevant as a predictor of RTX response in RA.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AK was involved in conception and design of the study, acquisition of patient data, genotyping and drafted the paper. LÄ and LP were involved in design of the study, genotyping and interpretation of results. LC, AC, RFvV, SR-D and SS were involved in design of the study, acquisition of patient data and interpretation of result. All authors revised the draft paper.

Funding: This work was supported by the County Council of Östergötland, the Tore Nilson Foundation and the Reinhold Sund Foundation.

Competing interests: RFvV has received research support and honoraria from Roche. All other authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Ethics approval: The regional ethics committees in Linköping, Stockholm and Umeå, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Wu J, Edberg JC, Redecha PB, et al. A novel polymorphism of FcgammaRIIIa (CD16) alters receptor function and predisposes to autoimmune disease. J Clin Invest 1997;100:1059–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cartron G, Dacheux L, Salles G, et al. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcgammaRIIIa gene. Blood 2002;99:754–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treon SP, Hansen M, Branagan AR, et al. Polymorphisms in FcgammaRIIIA (CD16) receptor expression are associated with clinical response to rituximab in Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:474–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchida J, Hamaguchi Y, Oliver JA, et al. The innate mononuclear phagocyte network depletes B lymphocytes through Fc receptor-dependent mechanisms during anti-CD20 antibody immunotherapy. J Exp Med 2004;199:1659–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dall'Ozzo S, Tartas S, Paintaud G, et al. Rituximab-dependent cytotoxicity by natural killer cells: influence of FCGR3A polymorphism on the concentration-effect relationship. Cancer Res 2004;64:4664–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruyssen-Witrand A, Rouanet S, Combe B, et al. Fcgamma receptor type IIIA polymorphism influences treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with rituximab. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:875–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kastbom A, Ahmadi A, Soderkvist P, et al. The 158V polymorphism of Fc gamma receptor type IIIA in early rheumatoid arthritis: increased susceptibility and severity in male patients (the Swedish TIRA project). Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:1294–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YH, Ji JD, Song GG. Associations between FCGR3A polymorphisms and susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis: a metaanalysis. J Rheumatol 2008;35:2129–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thabet MM, Huizinga TW, Marques RB, et al. Contribution of Fcgamma receptor IIIA gene 158V/F polymorphism and copy number variation to the risk of ACPA-positive rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1775–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson JI, Barrett JH, Taylor JC, et al. Dissection of the FCGR3A association with RA: increased association in men and with autoantibody positive disease. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1054–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kramer PR, Winger V, Kramer SF. 17beta-estradiol utilizes the estrogen receptor to regulate CD16 expression in monocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2007;279:16–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Gestel AM, Prevoo ML, van't Hof MA, et al. Development and validation of the European League against rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Comparison with the preliminary American College of Rheumatology and the World Health Organization/International League against Rheumatism Criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kastbom A, Bratt J, Ernestam S, et al. Fcgamma receptor type IIIA genotype and response to tumor necrosis factor alpha-blocking agents in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:448–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anolik JH, Campbell D, Felgar RE, et al. The relationship of FcgammaRIIIa genotype to degree of B cell depletion by rituximab in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:455–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cambridge G, Leandro MJ, Edwards JC, et al. Serologic changes following B lymphocyte depletion therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:2146–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosengren S, Wei N, Kalunian KC, et al. Elevated autoantibody content in rheumatoid arthritis synovia with lymphoid aggregates and the effect of rituximab. Arthritis Res Ther 2008;10:R105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor RP, Lindorfer MA. Drug insight: the mechanism of action of rituximab in autoimmune disease—the immune complex decoy hypothesis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2007;3:86–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niederer HA, Willcocks LC, Rayner TF, et al. Copy number, linkage disequilibrium and disease association in the FCGR locus. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19:3282–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.