Abstract

Objective:

To assess the prevalence and comorbid conditions of nocturnal wandering with abnormal state of consciousness (NW) in the American general population.

Methods:

Cross-sectional study conducted with a representative sample of 19,136 noninstitutionalized individuals of the US general population ≥18 years old. The Sleep-EVAL expert system administered questions on life and sleeping habits; health; and sleep, mental, and organic disorders (DSM-IV-TR; International Classification of Sleep Disorders, version 2; International Classification of Diseases–10).

Results:

Lifetime prevalence of NW was 29.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 28.5%–29.9%). In the previous year, NW was reported by 3.6% (3.3%–3.9%) of the sample: 1% had 2 or more episodes per month and 2.6% had between 1 and 12 episodes in the previous year. Family history of NW was reported by 30.5% of NW participants. Individuals with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (odds ratio [OR] 3.9), circadian rhythm sleep disorder (OR 3.4), insomnia disorder (OR 2.1), alcohol abuse/dependence (OR 3.5), major depressive disorder (MDD) (OR 3.5), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (OR 3.9), or using over-the-counter sleeping pills (OR 2.5) or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants (OR 3.0) were at higher risk of frequent NW episodes (≥2 times/month).

Conclusions:

With a rate of 29.2%, lifetime prevalence of NW is high. SSRIs were associated with an increased risk of NW. However, these medications appear to precipitate events in individuals with a prior history of NW. Furthermore, MDD and OCD were associated with significantly greater risk of NW, and this was not due to the use of psychotropic medication. These psychiatric associations imply an increased risk due to sleep disturbance.

Parasomnias are physical events or experiences that interfere with sleep. They can occur at sleep onset, during sleep, or during arousals from sleep. Sleepwalking is a disorder of arousal from non–REM (NREM) sleep parasomnia occurring predominantly during stages 3 or 4. Other sleep disorders, such as confusional arousals, nocturnal epilepsy, or sleep terrors, can be accompanied by episodes of nocturnal wanderings. These disorders may result in injuries to the individual or to others1–3 and may have forensic implications.2,4 Consequences include impaired psychosocial functioning. Sleepwalking is very common during childhood, reaching up to 30% in some studies,5,6 and decreasing with age. In adults, the few epidemiologic studies that have been carried out have reported 1-year prevalence around 3%.7,8 Prevalence rates for other arousal parasomnias are not well known. Confusional arousals in adults have been estimated at 4.3% in adults.8

Several predisposing and precipitating factors have been described for sleepwalking. Surprisingly, this identification was derived mainly from clinical experience or case reports rather than from scientific evidence.9–11 For example, sleep deprivation, fragmented sleep, and deep sleep are considered potent triggers for sleepwalking episodes and other parasomnias. However, clinical studies have reported mixed results.12,13 The same can be said for psychotropic medications and alcohol use as triggers for sleepwalking. The evidence is based solely on case reports.14–17

This study assesses the prevalence of nocturnal wandering with abnormal state of consciousness in the American general population. It also evaluates the importance of medication consumption, sleep, and mental disorders associated with nocturnal wandering.

METHODS

Sample.

Fifteen states were selected to represent the US population based on the number of inhabitants, and the geographic area: Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Missouri, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming. The final sample included 19,136 individuals representative of the general population of these states (138 million). Of 19,136 eligible adults, 15,929 completed interviews were obtained, providing a 83.2% cooperation rate, using CASRO (Council of American Survey Research Organizations) standards.

Procedures.

First, telephone numbers were retrieved in proportion to the population size of each county in the represented states. Telephone numbers were randomly selected within each state using a computerized residential phone book. Second, during the telephone contact, the Kish method18 was used to select 1 respondent per household. This method allowed for the selection of a respondent based on age and gender to maintain a sample representative of these 2 parameters.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Interviewers explained the goals of the study to potential participants and requested verbal consent before conducting the interview. The participants had the option of calling the principal investigator if they wanted further information. The study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

Subjects who declined to participate or who gave up before completing half the interview were classified as refusals. Excluded from the study were subjects who were not fluent in English or Spanish, who had a hearing or speech impairment, or who had an illness (such as dementia or AD, or a terminal disease) that precluded being interviewed. The interviews lasted on average 62.1 (±32.2) minutes. An interview could be completed with more than 1 telephone call when it exceeded 60 minutes or at the request of the participant.

Instrument.

The Sleep-EVAL knowledge-based expert system was used in this study to conduct the interviews.19,20 This computer software and its questionnaire were specially designed to conduct epidemiologic studies in the general population.

The system is composed of a nonmonotonic, level 2 inference engine, 2 neural networks, a mathematical processor, the knowledge base, and the base of facts. Simply put, the interview began with a series of questions asked of all the participants. Questions were read aloud by the interviewer as they appeared on the screen. These questions were either closed-ended (e.g., yes/no, 5-point scale, multiple choice) or open-ended (e.g., duration of symptoms, description of illness).

Once this information was collected, the system began the diagnostic exploration of mental disorders. On the basis of responses provided by a subject to this questionnaire, the system formulated an initial diagnostic hypothesis that it attempted to confirm or reject by asking supplemental questions or by deductions. Concurrent diagnoses are allowed in accordance with the DSM-IV-TR21 and the Classification of Sleep Disorders or International Classification of Sleep Disorders, version 2 (ICSD-II).22 The system terminated the interview once all diagnostic possibilities were exhausted.

The differential process is based on a series of key rules allowing or prohibiting the co-occurrence of 2 diagnoses. The questionnaire of the expert system is designed such that the decision about the presence of a symptom is based upon the interviewee's responses rather than on the interviewer's judgment. This approach has proved to yield better agreement between lay interviewers and psychiatrists on the diagnosis of minor psychiatric disorders.23 The system has been tested in various contexts, in clinical psychiatry and sleep disorders clinics.24–27 In psychiatry, overall κ between psychiatrists and the system was 0.7125; κs have ranged from 0.44 (schizophrenia disorders) to 0.78 (major depressive disorder). Agreement for insomnia diagnoses was obtained in 96.9% of cases (κ 0.78). Overall agreement on any breathing-related sleep disorder was 96.9% (κ 0.94).24,26 For excessive sleepiness as a symptom, κ between Sleep-EVAL and 3 sleep specialists ranged from 0.62 to 0.70 with an overall sensitivity of 98.3% and a specificity of 62.5%. For narcolepsy with cataplexy, κs between sleep specialists on the presence of narcolepsy ranged from 0.83 to 0.93 while κs between Sleep-EVAL and each sleep specialist were 0.89, 0.93, and 1.0.27

Variables.

Information gathered related to nocturnal wandering included the following: frequency of episodes during sleep; duration of the sleep disorder; partial or complete amnesia of the episode; difficulty in being aroused during an episode; mental confusion when awakened from an episode; routine or inappropriate behaviors during sleep; dangerous or potentially dangerous behavior during sleep. Participants who did not report episodes in the previous year were asked if they ever had such episodes in their childhood or adolescence (if so, at what approximate age they started and approximate age they ended).

Participants were also assessed on frequency and duration of other parasomnia symptoms (confusional arousals, sleep terrors, violent behaviors during sleep, hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations); and medications, which were grouped according to their drug class and approved label: e.g., antipyretic analgesic, narcotic analgesic, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, benzodiazepine anxiolytic, benzodiazepine hypnotic, nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic, over-the-counter sleep aid, antipsychotic, anticonvulsant, CNS stimulants, skeletal muscle relaxant.

Sleep disorder diagnoses were assessed according to DSM-IV-TR and ICSD-II classifications respecting positive and differential diagnosis processes. Mental disorders were evaluated using the DSM-IV-TR classification.

Analyses.

A weighting procedure was applied to correct for disparities in the geographic, age, and sex distributions between the sample and the populations of different states. Results were based on weighted n values and percentages. Logistic regressions were used to compute the odds ratios (OR) associated with nocturnal wandering. Reported differences were significant at the 0.01 level or less (determined using the Holm-Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons).28 SPSS version 19 was used to perform statistical analyses.

RESULTS

From 19,136 solicited individuals, data from 15,929 participants, aged from 18 to 102 years, were included in the analyses. Fifty-nine percent were living in areas with a population density >200 inhabitants per square mile. Women represented 51.3% of the sample. More than half (53.5%) of the sample were married or living with someone.

Nearly 40% of the sample was working on a daytime schedule; shift work (i.e., working outside regular daytime hours) represented about 20% of the sample.

Prevalence.

As many as 3.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.3%–3.9%) of the sample reported at least 1 episode of NW in the previous year: 0.2% (0.1%–0.3%) reported episodes occurring at least once per week; an additional 0.8% (0.7%–0.9%) of the sample reported having 2 to 3 episodes of NW per month and an additional 2.6% (2.4%–2.8%) had 1 to 12 episodes in the previous year.

A history of NW during childhood or adolescence (and without any episodes in the previous year) was reported by 25.7% (25.0%–26.4%) of the sample. Consequently, lifetime prevalence of NW was 29.2% (28.5%–29.9%).

The duration of NW was mostly chronic: 7.2% had NW episodes for less than 6 months, 5.8% for 6 to 12 months, an additional 6.2% for 1 to 5 years, and 80.5% for more than 5 years.

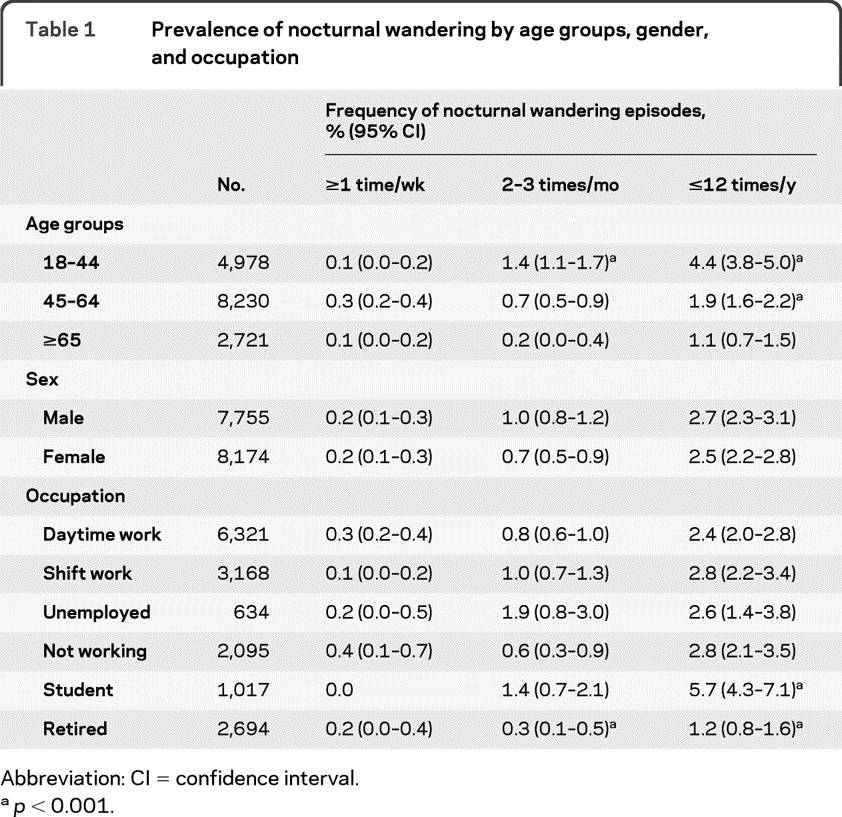

As seen in table 1, NW was not associated with gender but it significantly decreased with age with the exception of the category ≥1 time per week. As could be expected, NW was less frequently reported by retired individuals in the categories 2–3 times/month and ≤12 times/year.

Table 1.

Prevalence of nocturnal wandering by age groups, gender, and occupation

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

p < 0.001.

Family history.

Individuals reporting episodes of NW in the previous year were more likely than the rest of the sample to report a family history of NW: 30.5% of them reported had at least 1 family member who had experienced NW episodes compared with 17.2% in the rest of the sample (OR 2.12 [1.74–2.59]; p < 0.0001). More precisely, 2.9% reported their mother had NW episodes compared to 0.6% of the rest of the sample (p < 0.001) and 6.3% of NW individuals reported their father had NW episodes (vs 0.9%; p < 0.001). A total of 11.4% of individuals with NW reported at least 1 of their siblings had NW episodes, compared to 7.8% in the rest of the sample (p < 0.01). For participants with children, the proportion of NW in offspring was higher among individuals with NW than for the others (14.9% vs 8.9%; p < 0.001).

Associated factors.

Logistic regressions were performed to determine factors associated with the presence of NW. The first model compared individuals with NW episodes occurring at least 2 times per month to individuals who never had NW episodes. The second model compared individuals reporting at least 1 episode in the previous year to the rest of the sample.

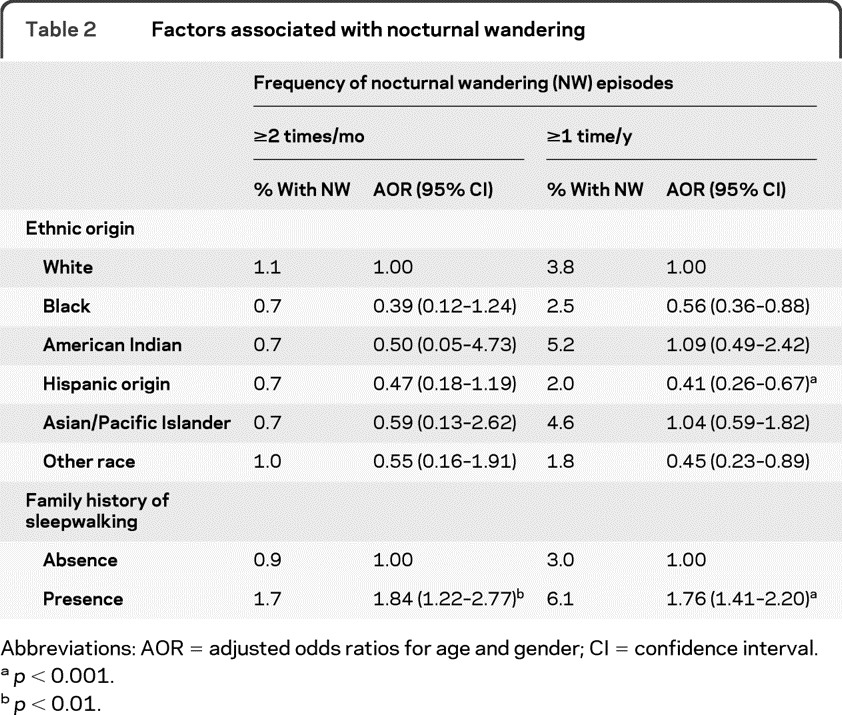

Individuals with family history of NW were more likely to report NW episodes in both models. Hispanics were less likely than white individuals to report NW occurring at least 1 time per year (table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with nocturnal wandering

Abbreviations: AOR = adjusted odds ratios for age and gender; CI = confidence interval.

p < 0.001.

p < 0.01.

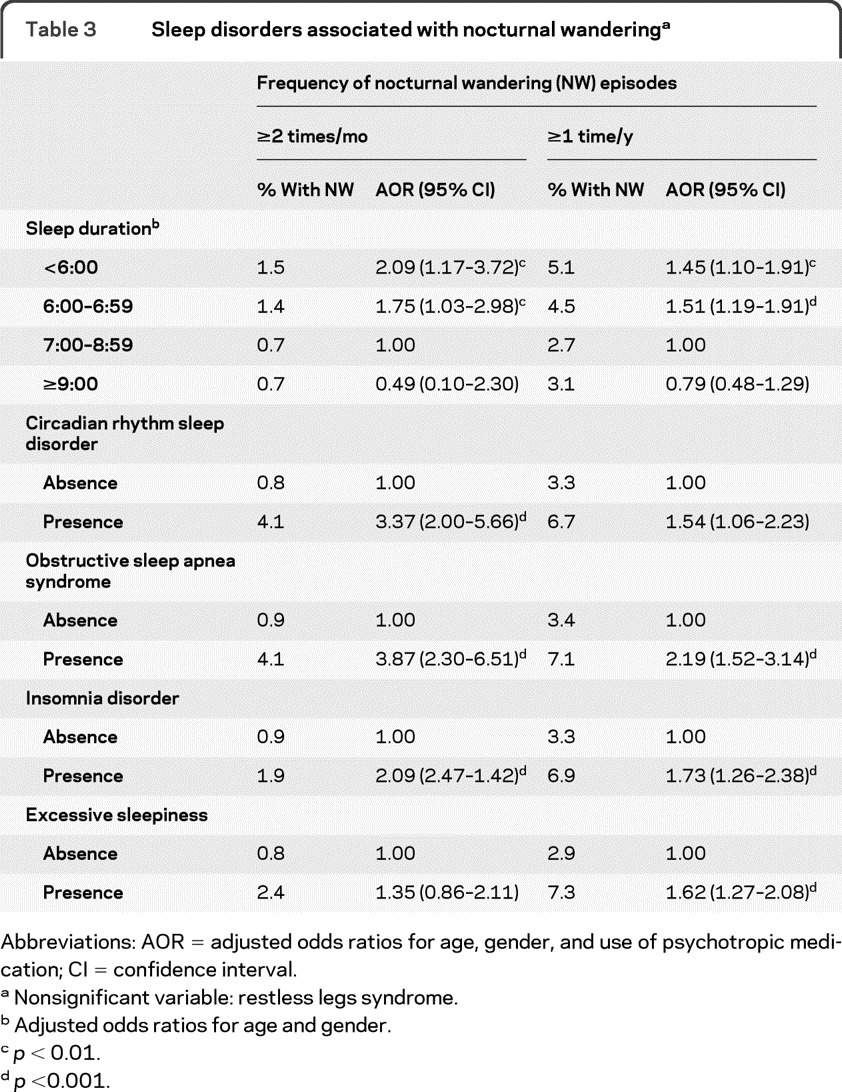

As seen in table 3, among sleep disorders, circadian rhythm sleep disorder, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and insomnia disorder predicted more frequent NW episodes (≥2 times/month). Circadian rhythm sleep disorder was no longer significant but excessive sleepiness was significantly associated with having at least 1 NW episode in the previous year. In both models, ORs were adjusted for age, gender, and use of psychotropic medication.

Table 3.

Sleep disorders associated with nocturnal wanderinga

Abbreviations: AOR = adjusted odds ratios for age, gender, and use of psychotropic medication; CI = confidence interval.

Nonsignificant variable: restless legs syndrome.

Adjusted odds ratios for age and gender.

p < 0.01.

p <0.001.

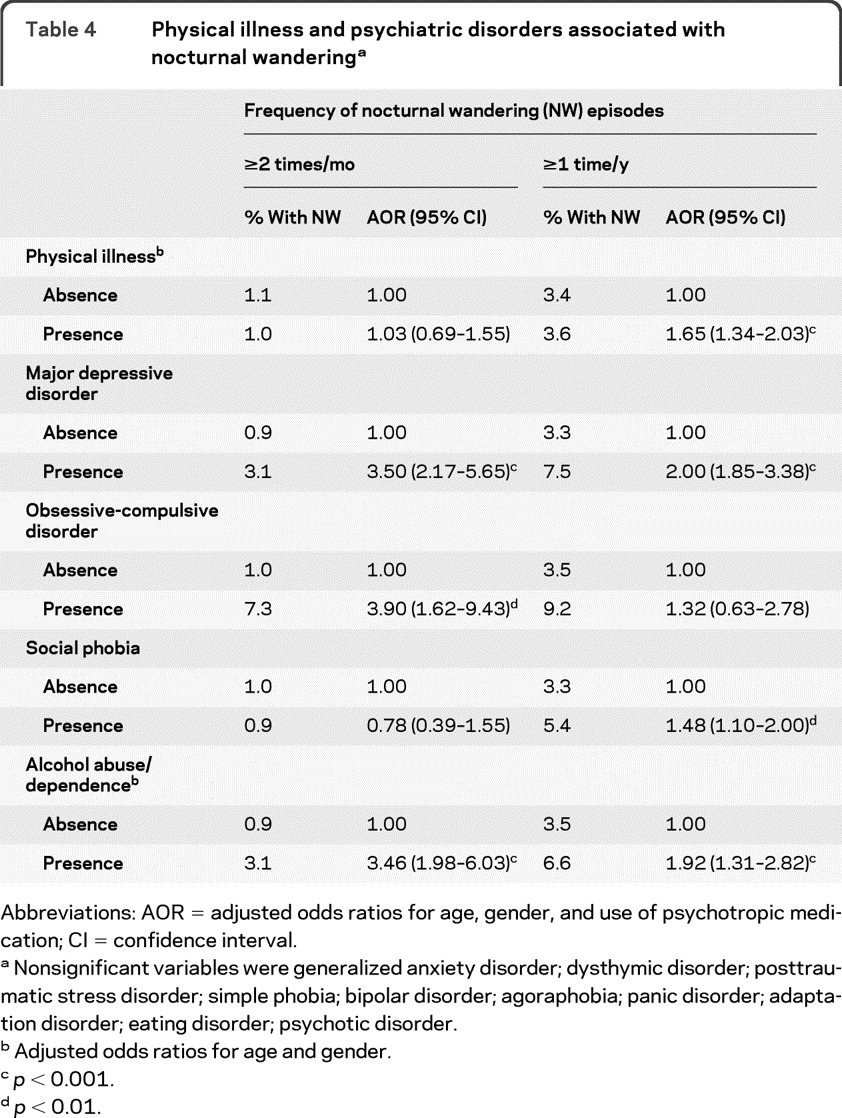

Among mental disorders (table 4), after adjusting for age, gender, and use of psychotropic medication, individuals with alcohol abuse/dependence, major depressive disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder were significantly more likely to have NW episodes at least 2 times per month. Conversely, major depressive disorder, social phobia, alcohol abuse/dependence, and presence of physical illness were associated with having at least 1 NW episode in the previous year.

Table 4.

Physical illness and psychiatric disorders associated with nocturnal wanderinga

Abbreviations: AOR = adjusted odds ratios for age, gender, and use of psychotropic medication; CI = confidence interval.

Nonsignificant variables were generalized anxiety disorder; dysthymic disorder; posttraumatic stress disorder; simple phobia; bipolar disorder; agoraphobia; panic disorder; adaptation disorder; eating disorder; psychotic disorder.

Adjusted odds ratios for age and gender.

p < 0.001.

p < 0.01.

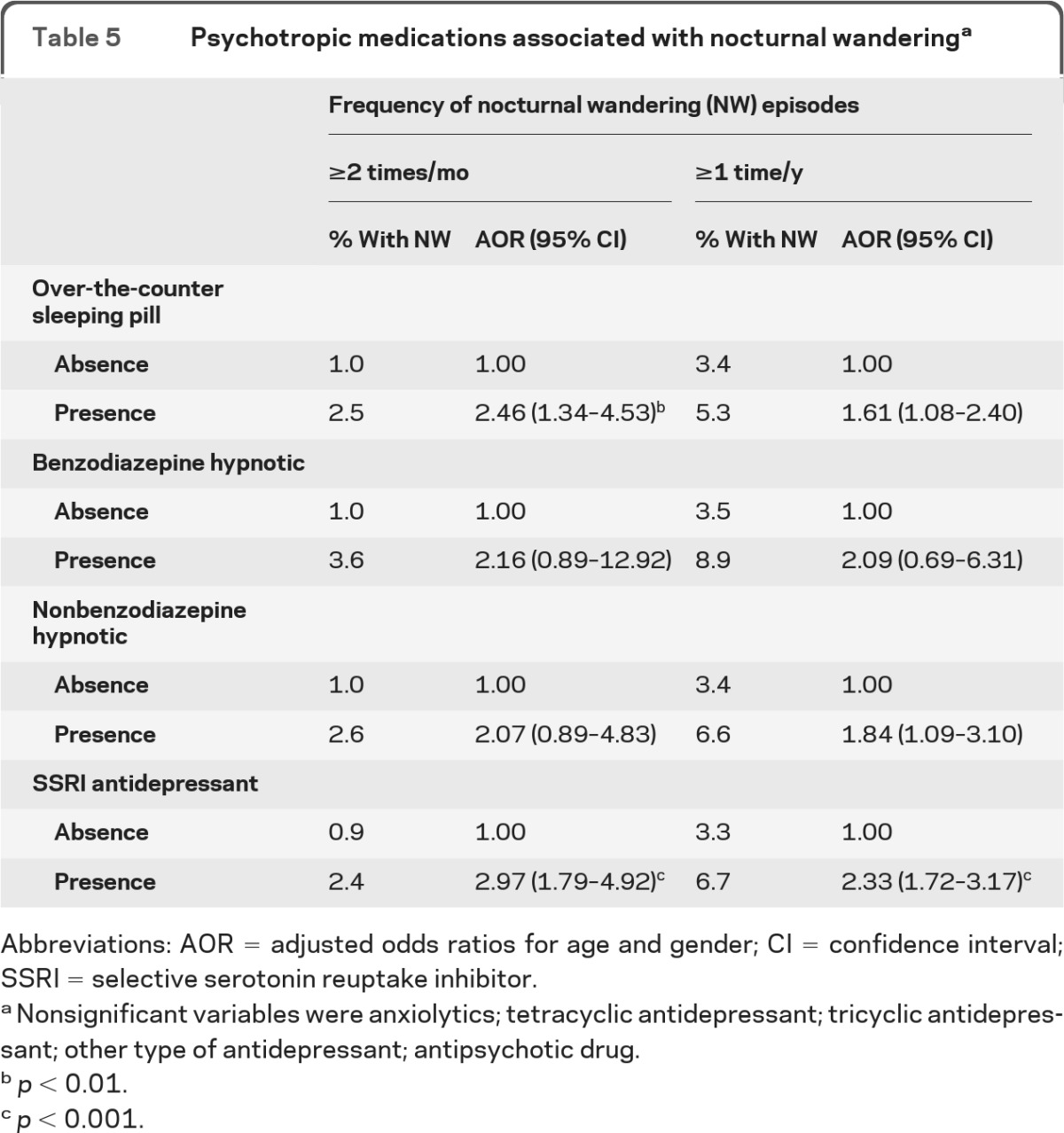

When examining the use of psychotropic medication (table 5), it was found that individuals using SSRI antidepressants and those using over-the-counter sleeping pills had a higher likelihood of reporting NW episodes at least 2 times per month. Use of SSRI antidepressant was also associated with the report of at least 1 episode of NW in the previous year.

Table 5.

Psychotropic medications associated with nocturnal wanderinga

Abbreviations: AOR = adjusted odds ratios for age and gender; CI = confidence interval; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Nonsignificant variables were anxiolytics; tetracyclic antidepressant; tricyclic antidepressant; other type of antidepressant; antipsychotic drug.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

We have also examined the use of medication according to main indication as reported by the participants. Medications were separated into 4 main categories: prescribed for “sleep,” “anxiety,” “depression,” and a residual category “other purposes.” The results did not substantially change. Individuals using over-the-counter sleeping pills (OR 2.50 [1.35–4.61]) and those using tricyclic antidepressants (OR 17.78 [1.69–>50.0]) were at higher risks of having NW episodes at least 2 times per month. Individuals using SSRI antidepressants taken for anxiety were more likely to report NW episodes occurring at least once per year (OR 2.33 [1.50–3.63]).

Finally, we also verified whether NW duration was associated with the intake of any kind of psychotropic drugs. Individuals taking an antidepressant, an anxiolytic, or a hypnotic medication had NW episodes for as long as those without medication. We found more NW individuals with antidepressants who had NW for less than 6 months (12.2%) compared to the other NW participants (6.6%), but the difference was nonsignificant (p = 0.444).

DISCUSSION

This study, based on a large representative sample of the US general population, is the first to demonstrate the prevalence of nocturnal wandering in the community. Precisely, 3.6% of the sample had more than 1 episode of nocturnal wandering in the previous year. Apart from a study we did 10 years ago in the European general population,7 where we reported a prevalence of 2% of sleepwalking, there are nearly no data regarding the prevalence of nocturnal wanderings in the adult general population. In the United States, the only prevalence rate was published 30 years ago. This study reported a prevalence of 2.5% of sleepwalking in a sample of 1,006 adults living in the Los Angeles metropolitan area.6

There are several noteworthy results in our study. Sleep fragmentation was proposed as a marker for sleepwalking.12,29,30 In our study, however, nocturnal awakenings were significantly associated with nocturnal wanderings only in bivariate analyses. It became nonsignificant in the multivariate model, which means that the association is explained by other factors, such as obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Recent controlled clinical studies have shown that a large proportion of sleepwalkers also have sleep-disordered breathing and that sleepwalking disappears once affected individuals are treated for the breathing disorder.31,32 Furthermore, sudden arousals from slow-wave sleep were found to have a low specificity for NREM parasomnias.29 Additionally, one should keep in mind that in this study, nocturnal awakenings were based on self-report; we could not therefore account for arousals or microarousals because the participants were unaware of them. This would suggest that the sleep fragmentation in sleepwalkers might be mostly in the form of arousals and microarousals rather than complete awakenings.

Sleep restriction was also reported as a possible trigger for sleepwalking episodes.13,33 In this study, we did find a higher risk of having at least 1 nocturnal wandering episode in the previous year in individuals sleeping less than 7 hours per night after adjusting for possible confounding factors such as age, sleep, and mental disorder.

Several cases of sleepwalking associated with the intake of psychotropic medication (antidepressant, hypnotic, normothymic, neuroleptic) have been reported in the literature.14,15 However, these reports remain incidental. For most of these cases, it is impossible to tell whether the patient was sleepwalking or had episodes of nocturnal wandering (i.e., the patient is awake but is confused and has no memory of the episode upon awakening). Many of these patients had complex medical and psychiatric histories and were heavily medicated. Consequently, the causality between the use of a specific psychotropic medication and the appearance of sleepwalking episodes is not as obvious as it may appear. Furthermore, our results show that individuals taking psychotropic medication (antidepressants, anxiolytics, or hypnotics) were having nocturnal wandering episodes for as long as those without medication. Consequently, it seems unlikely that these medications cause nocturnal wandering, but rather that they appear to trigger events in predisposed individuals. We did find a higher risk of frequent nocturnal wandering episodes among individuals with insomnia disorder but not with hypnotic intake (benzodiazepine or benzodiazepine-like hypnotics). This suggests, as mentioned earlier, that sleep restriction or sleep fragmentation (because of the insomnia) might be involved in sleepwalking and nocturnal wandering.

It has been suggested that the serotonergic system may be involved in sleepwalking.34 In our study, the associations between SSRI antidepressants, major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and nocturnal wandering would support the hypothesis of a serotonin involvement in sleepwalking. Studies have not been carried out examining the relationship between sleepwalking and depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder while controlling for the effects of antidepressant medications. The same conclusion can be drawn for most mental disorders. There are several case reports of medications appearing to induce sleepwalking in psychiatric patients but almost no studies that have examined the incidence of mental disorders in sleepwalking individuals or vice versa. We have recalculated the multivariate models excluding all participants who were treated with a psychotropic drug to verify if the observed associations remained significant. They all remained significant. Therefore, the association between major depressive disorder and nocturnal wandering could not be attributed to the intake of a psychotropic medication. This was the same for obsessive-compulsive disorder: the association persisted in the absence of psychotropic treatment.

We also found that nearly one-third of individuals with nocturnal wandering had a family history of such disorder. A strong familial occurrence has often been reported in sleepwalking; for example, a prospective study35 reported a sleepwalking occurrence of 14% in children aged between 8 and 10 years who had 1 of their parents with sleepwalking history and 2% of sleepwalking in children with nonsleepwalking parents. The Finnish cohort twin study reported a higher concordance among monozygotic compared to dizygotic twins and another study has shown a 10-fold increase of sleepwalking among first-degree relatives of sleepwalkers compared to the general population.36 Recently, a genetic study highlighted that sleepwalking appears to be an autosomal dominant disorder with reduced penetrance and with chromosome 20q12-q13.12 localization for a gene responsible for the disorder.37

It should be kept in mind, however, that our results are based on subjective reports. Since ours is an epidemiologic study, we did not conduct laboratory testing with respondents to confirm diagnoses. Sleepwalking, however, does not require polysomnographic recording to confirm the diagnosis. However, given the absence of objective measures of sleepwalking, because complete or partial amnesia is one of the characteristics of this sleep disorder, it is likely that sleepwalking was underreported, especially among participants living alone. Nonetheless our data provide critical information regarding this understudied sleep disorder.

Historically, sleepwalking has been believed to be associated with psychological or psychiatric conditions, particularly if it begins in, or persists into, adulthood. This study supports the organic nature of sleepwalking, and underscores the fact that sleepwalking is much more prevalent in adults than previously appreciated. It is now clear that sleepwalking represents an admixture of wakefulness and sleep, supporting the fact that sleep is not a global, whole-brain phenomenon.38–40

GLOSSARY

- CI

confidence interval

- DSM-IV-TR

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision

- ICSD-II

International Classification of Sleep Disorders, version 2

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- NREM

non–REM

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- NW

nocturnal wandering

- OCD

obsessive-compulsive disorder

- OR

odds ratio

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in the conception and design or analysis and interpretation of data, have contributed to the drafting and revisions of the manuscript, and have approved the submitted version.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schenck CH, Milner DM, Hurwitz TD, Bundlie SR, Mahowald MW. A polysomnographic and clinical report on sleep-related injury in 100 adult patients. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146: 1166–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. A polysomnographically documented case of adult somnambulism with long-distance automobile driving and frequent nocturnal violence: parasomnia with continuing danger as a noninsane automatism? Sleep 1995; 18: 765–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guilleminault C, Leger D, Phillip P, Ohayon MM. Nocturnal wandering and violence: Review of a sleep clinic population. J Forensic Sci 1998; 43: 158–163 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bornemann MA, Mahowald MW, Schenck CH. Parasomnias. Clinical features and forensic implications. Chest 2006; 130: 605–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jacobson A, Kales JD, Kales A. Clinical and electrophysiological correlates of sleep disorders in children. In: Kales A. ed. Sleep: Physiology and Pathology. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1969: 109–118 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nevéus T, Cnattingius S, Olsson U, Hetta J. Sleep habits and sleep problems among a community sample of schoolchildren. Acta Paediatr 2001; 90: 1450–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bixler EO, Kales A, Soldatos CR, Kales JD, Healey S. Prevalence of sleep disorders in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Am J Psychiatry 1979; 136: 1257–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ohayon MM, Guilleminault C, Priest RG. Night terrors, sleepwalking, and confusional arousals in the general population: their frequency and relationship to other sleep and mental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60: 268–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raschka LB. Sleep and violence. Can J Psychiatry 1984; 29: 132–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mahowald MW, Schenck CH. Parasomnias: sleepwalking and the law. Sleep Med Rev 2004; 4: 321–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. An analysis of a recent criminal trial involving sexual misconduct with a child, alcohol abuse and a successful sleepwalking defense: arguments supporting two proposed new forensic categories. Med Sci Law 1998; 38: 147–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Joncas S, Zadra A, Paquet J, Montplaisir J. The value of sleep deprivation as a diagnostic tool in adult sleepwalkers. Neurology 2002; 58: 936–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pilon M, Montplaisir J, Zadra A. Precipitating factors of somnambulism: impact of sleep deprivation and forced arousals. Neurology 2008; 70: 2284–2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hafeez ZH, Kalinowski CM. Somnambulism induced by quetiapine: two case reports and a review of the literature. CNS Spectr 2007; 12: 910–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sattar SP, Ramaswamy S, Bhatia SC, Petty F. Somnambulism due to probable interaction of valproic acid and zolpidem. Ann Pharmacother 2003; 37: 1429–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Zolpidem, somnambulism, and nocturnal eating. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008; 30: 90–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pressman M. Factors that predispose, prime and precipitate NREM parasomnias in adults: clinical and forensic implications. Sleep Med Rev 2007; 11: 5–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kish L. Survey Sampling. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ohayon MM. Sleep-EVAL: Knowledge Based System for the Diagnosis of Sleep and Mental Disorders: Copyright Office, Canadian Intellectual Property Office. Ottawa: Industry Canada; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ohayon MM. Improving decision-making processes with the fuzzy logic approach in the epidemiology of sleep disorders. J Psychosom Res 1999; 47: 297–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22. American Academy of Sleep Medicine The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. Rochester, MN: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya RC, Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community, a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med 1992; 22: 465–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ohayon MM, Guilleminault C, Zulley J, Palombini L, Raab H. Validation of the Sleep-EVAL system against clinical assessments of sleep disorders and polysomnographic data. Sleep 1999; 22: 925–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ohayon M. Validation of expert systems: Examples and considerations. Medinfo 1995; 8: 1071–1075 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hosn R, Shapiro CM, Ohayon MM. Diagnostic concordance between sleep specialists and the Sleep-EVAL system in routine clinical evaluations. J Sleep Res 2000; 9(suppl 1): 86 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Black J, Ohayon MM, Okun M, Guilleminault C, Mignot E, Zarcone V. The narcolepsy diagnosis: comparison between the Sleep-EVAL system and clinicians. Sleep 2001; 24(abst suppl): A328 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 1979; 6: 65–70 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pressman MR. Hypersynchronous delta sleep EEG activity and sudden arousals from slow wave sleep in adults without a history of parasomnias: clinical and forensic implications. Sleep 2004; 27: 706–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gadreau H, Joncas S, Zadra A, Montplaisir J. Dynamics of slow-wave activity during the NREM sleep of sleepwalkers and control subjects. Sleep 2000; 23: 755–760 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guilleminault C, Kirisoglu C, Bao G, Arias V, Chan A, Li KK. Adult chronic sleepwalking and its treatment based on polysomnography. Brain 2005; 128: 1062–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Espa F, Dauvilliers Y, Ondze B, Billiard M, Besset A. Arousal reactions in sleepwalking and night terrors in adults: the role of respiratory events. Sleep 2002; 25: 871–875 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zadra A, Pilon M, Montplaisir J. Polysomnographic diagnosis of sleepwalking: effects of sleep deprivation. Ann Neurol 2008; 63: 513–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Juszczak GR, Swiergiel AH. Serotonergic hypothesis of sleepwalking. Med Hypoth 2005; 64: 28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abe K, Amatomi M, Oda N. Sleepwalking and recurrent sleeptalking in children of childhood sleepwalkers. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141: 800–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hublin C, Kaprio J, Partinen M, Heikkila K, Koskenvuo M. Prevalence and genetics of sleepwalking: a population-based twin study. Neurology 1997; 48: 177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Licis AK, Desruisseau DM, Yamada KA, Duntley SP, Gurnett CA. Novel genetic findings in an extended family pedigree with sleepwalking. Neurology 2011; 76: 49–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mahowald MW, Cramer Bornemann MA, Schenck CH. State dissociation: implications for sleep and wakefulness, consciousness, and culpability. Sleep Medicine Clinics 2011; 6: 393–400 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Terzaghi M, Sartori I, Tassi L, et al. Evidence of dissociated arousal states during NREM parasomnia from an intracerebral neurophysiological study. Sleep 2009; 32: 409–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nobili L, Ferrara M, Moroni F, et al. Dissociated wake-like and sleep-like electro-cortical activity during sleep. Neuroimage 2011; 58: 612–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]