Abstract

Objective

A new nicotine mouth spray was shown to be an effective stop-smoking treatment. This study was set up to examine the speed with which it relieves urges to smoke, and how it compares with nicotine lozenge in this respect.

Design

Randomised, cross-over trial that compared nicotine mouth spray 2 mg versus nicotine lozenge 2 or 4 mg.

Setting

Clinical pharmacology research unit.

Participants

200 Volunteer smokers who smoked their first cigarette of the day within 30 min of waking.

Interventions

Subjects abstained from smoking the night before the morning they attended the laboratory. Treatment was administered following 5 h of witnessed abstinence.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Urge to smoke was rated before and at 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 25, 30, 45 min and 1, 1.5, and 2 h after treatment administration. The primary outcome concerned change during the first 1, 3 and 5 min after treatment administration.

Results

Nicotine mouth spray achieved greater reductions in craving than either lozenge during the first 1, 3 and 5 min postadministration. After using mouth spray, half of the users experienced 50% reduction in craving within 3.40 min, while the same treatment effect was achieved within 9.92 and 9.20 min for the 2 and 4 mg lozenge, respectively. Adverse events with both mouth spray and lozenge were mostly mild. Hiccups, local irritation, nausea and dyspepsia were more frequent with spray than lozenge.

Conclusions

Nicotine mouth spray provides a faster relief of cravings than nicotine lozenge.

Article Summary.

Article focus

There is some evidence that nicotine replacement therapies (NRT) formulations which act faster in relieving cravings for cigarettes are overall more effective at relieving withdrawal discomfort.

Nicotine mouth spray provides a faster nicotine delivery than traditional oral nicotine replacement products and long-term efficacy of nicotine mouth spray, in terms of smoking abstinence, has been demonstrated in a placebo-controlled study. No clinical data on direct comparisons with other NRT products is currently available.

This study was set up to examine whether the fast delivery of nicotine from the mouth spray is paralleled by a fast craving relief and how the mouth spray compares to other oral NRT products in this respect.

Key messages

Results suggest that nicotine mouth spray reduces urges to smoke faster than nicotine lozenge.

The mouth spray represents an important new development in extending the range of nicotine replacement treatments, and may potentially also improve their efficacy.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Previous findings that nicotine is absorbed faster from the mouth spray than the lozenge provides a rationale for considering the faster relief of craving to be a clinically reproducible effect. Furthermore, our results reflect the findings of an earlier study of another nicotine mouth spray which reduced craving significantly faster than nicotine 2 mg gum.

Our trial used an active comparator but did not include a placebo arm and participant allocation could not be blinded. In addition to speed of absorption and sensory effects, the novelty of the mouth spray, distraction due to its mode of administration and participant and staff expectations could conceivably have impacted on the study results.

Introduction

There are currently several nicotine replacement therapies (NRT) available for smokers who seek help in stopping smoking. These medications are of proven efficacy but there remains scope for improvement of long-term success rates.1 There is some evidence that NRT formulations that act faster in relieving cravings for cigarettes are overall more effective at relieving withdrawal discomfort.2 3 Such medications may be particularly useful in alleviating intermittent urges to smoke when a fast reduction in temptation is considered important in order to prevent lapse to smoking. Currently available oral NRT formulations provide craving relief relatively slowly. Nicotine nasal spray has more immediate effects4 but it initially causes unpleasant local irritation. The nasal spray is also a prescription-only medication in a number of countries.

Delivering nicotine via a mouth spray is one promising approach to a faster and more palatable form of nicotine delivery. Compared with chewing gum, lozenge or sublingual tablet, mouth spray delivers nicotine in solution quickly on a large surface area of the buccal mucosa. The current study examined a new nicotine mouth spray that delivers 1 mg of nicotine in each metered dose. Pharmacokinetic studies have shown that nicotine mouth spray delivers blood nicotine levels comparable to that of other NRT formulations of the same strength,5 but that the mouth spray reaches maximum blood concentrations in approximately 10 min, which is significantly faster than the other oral NRT formats.5

Long-term efficacy of nicotine mouth spray, in terms of smoking abstinence, has been demonstrated in a placebo-controlled study (sustained abstinence rates 15.7% vs 68% at 24 weeks).6 However, no clinical data on direct comparisons with other NRT products are currently available. The current study was performed to investigate the speed of subjects’ experienced relief from urges to smoke over the first few minutes after using the nicotine mouth spray and how the mouth spray compares to other oral NRT products in this respect.

Methods

Study design and aims

This randomised, cross-over trial investigated the effect of nicotine mouth spray on urges to smoke in healthy smokers who had abstained from smoking overnight prior to study treatment administration. The primary objective was to compare urges to smoke in the period immediately after administration of either 2 mg nicotine mouth spray, 2 mg nicotine lozenge or 4 mg nicotine lozenge. The study treatments were also compared with respect to the time to predefined reductions of the baseline urges to smoke score, and the proportion of subjects who reported predefined degrees of reduction of their baseline urges to smoke within 1, 3, 5 and 10 min postadministration. The trial was conducted at McNeil AB, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Lund, Sweden. The study was initiated on 1 February 2010 and completed by 19 May 2010. The trial protocol, developed by McNeil AB, was approved by the local Independent Ethics Committee in Lund, Sweden, and the Swedish Medical Products Agency, and the study was performed in accordance with current International Conference on Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. All subjects provided signed, informed consent before entering the study.

Participants

Healthy adult male and female smokers of at least 10 cigarettes/day, between 19 and 55 years old, who smoked their first cigarette of the day within 30 min of waking. Eligible subjects had to weigh at least 50 kg and have a body mass index of 17.5–32 kg/m2. Intention to stop smoking was not an explicit inclusion criterion.

Subjects who presented with any of the following were excluded: women who were either pregnant or breastfeeding; any pathological oral status that may have interfered with normal oral function or transmucosal absorption; use of any other nicotine replacement medication or bupropion or varenicline, or a quit attempt, within the 3-month period prior to the study; previous regular use of either nicotine mouth spray or lozenge; or regular alcohol consumption that exceeded weekly limits of 2 litre of wine or 5 litre of beer or 0.6 litre of spirits for women, and 3 litre of wine or 7.5 litre of beer or 0.9 litre of spirits for men.

Treatment periods and study medications

The study period comprised three separate treatment visits, with washout periods of at least 36 h between visits. Subjects were to abstain from smoking from 20:00 h in the evening before each treatment visit until the end of the visit at about 16:00 h. All subjects received two doses of each study treatment at each visit, one in the morning and another in the afternoon, 5 h after the first administration. The morning administration and measurements of urges to smoke allowed subjects to get used to the study treatments and rating scales.

The three study treatments administered were nicotine mouth spray 2 mg (Nicorette Mouth Spray 1 mg/spray, McNeil AB), nicotine lozenge 2 mg and nicotine lozenge 4 mg (NiQuitin Lozenge 2 and 4 mg, GlaxoSmithKline, Copenhagen, Denmark). The doses selected were based on the currently recommended single doses for nicotine lozenge and the maximum proposed single dose for nicotine mouth spray. A computer-generated randomisation schedule, produced by the sponsor, was used to randomly allocate the subjects to the different treatment sequences. Randomisation was balanced for the six possible treatment sequences by using randomisation blocks of size 12. Randomisation numbers were assigned sequentially to subjects at their first treatment visit.

After priming, the spray delivers 1 mg of nicotine per metered-dose spray. A 2 mg dose of mouth spray was administered as two consecutive sprays of the solution, sprayed into the mouth. Subjects were advised to avoid swallowing immediately after administration of the spray. The reference product, nicotine lozenge, is a widely used oral NRT product that effectively aids smoking cessation and has been shown to relieve craving.7 Subjects were instructed to place the nicotine 2 or 4 mg lozenge in their mouth and to occasionally move it from one side to the other until the lozenge had completely dissolved. They were instructed to not chew or swallow the lozenge. A lozenge typically dissolves in 20–30 min. Subjects did not eat or drink from 15 min before until 60 min after administration of each study treatment.

Assessments

Before entering the trial subjects underwent a physical examination, including vital signs, and provided a medical and smoking history.

Urges to smoke were scored on a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) 10, 6 and 2 min before and 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 45 min and 1, 1.5 and 2 h after treatment administration. On the VAS, zero represented ‘no urges to smoke’ and 100 mm represented ‘extreme urges to smoke’. Ratings of urges to smoke were collected using electronic subject diaries (eDiaries). The eDiary consisted of a hand-held computer that had been programmed to allow subjects to enter specific data and answer predefined questions. The study personnel demonstrated how to use the eDiary, and were present to assist while subjects used the eDiaries if any queries arose. All adverse events spontaneously reported by subjects were recorded, and subjects were also questioned about adverse events.

Statistical methods

The primary study endpoints were the area under the urges-to-smoke-versus-time curve (AUC) from start of administration until 1, 3 and 5 min postadministration (AUC1 min, AUC3 min and AUC5 min, respectively). Secondary endpoints were the AUC from start of the administration until 10 min (AUC10 min), the time to 25%, 50%, 75% and 90% reduction in urges to smoke score versus baseline, and the proportion of subjects who attained 25%, 50%, 75% and 90% reduction of urges to smoke, versus baseline, at 1, 3, 5 and 10 min.

The composite nature of the primary study objective motivated a Bonferroni-adjusted significance level of 2.5% and a target type-II error rate of 5% for each separate comparison. On the basis of previous data from a similar study, the within-subjects SD was assumed not to exceed 120 mm×min for any of the primary endpoints. Under these premises, to be able to detect a mean treatment difference of 50 mm×min with a balanced cross-over design and a two-sided analysis of variance-based test, in total 178 subjects (2×89) were needed. To allow for dropouts, recruitment continued until 200 subjects were included in the study.

The data set analysed for relief of craving comprised the data collected following administration of study treatments after 5 h of witnessed abstinence from smoking (the afternoon administration). All randomised subjects with any urges to smoke data were included in the pharmacodynamic analysis, and all subjects who received at least one dose of study treatment were analysed for safety.

Pair-wise treatment comparisons with respect to AUCn min (where n=1, 3, 5 and 10, that is, the area under the linearly interpolated urges-to-smoke-versus-time curve from time zero until n min) were based on a mixed linear model (SAS V.9.1, PROC MIXED) that included sequence, treatment, period and the baseline urges-to-smoke score as fixed effects, and subject, nested within sequence, as random effect. The baseline urges-to-smoke score was determined by the mean value of the three pretreatment assessments, 10, 6 and 2 min before administration.

Treating subject as a random factor in the model makes efficient use of all available valid data points. A post hoc sensitivity analysis of the primary endpoints based on the subset of subjects with complete and valid data from all three study periods (n=178) was also performed.

The possible effects of carry-over were assumed small relative to main effects of treatments, and in the primary analysis, no attempt was therefore made to test for this or any other treatment-by-period interaction. A post hoc sensitivity analysis of the primary endpoints restricted to valid data from the first session only, and consequently not affected by carry-over, showed similar results to the main findings presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Estimated mean (LSmean±SE) average changes in urges-to-smoke scores and corresponding comparisons between treatments (estimated treatment difference (97.5% CI) and Bonferroni-adjusted p value) at 1, 3, 5 and 10 min postadministration by treatment

| Average score changes from baseline (mm)* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Nicotine mouth spray 2 mg | Nicotine lozenge 2 mg | Nicotine lozenge 4 mg | Spray vs 2 mg lozenge | Spray vs 4 mg lozenge |

| 1 min | −11.91±0.72 | −3.97±0.72 | −4.80±0.72 | −7.9 (−9.8, −6.1) p<0.001 | −7.1 (−9.0, −5.2) p<0.001 |

| 3 min | −23.65±1.21 | −10.14±1.20 | −11.62±1.20 | −13.5 (−16.4, −10.6) p<0.001 | −12.0 (−14.9, −9.1) p<0.001 |

| 5 min | −29.19±1.32 | −15.27±1.31 | −17.03±1.31 | −13.9 (−16.9, −10.9) p<0.001 | −12.2 (−15.2, −9.2) p<0.001 |

| 10 min | −35.78±1.45 | −23.34±1.44 | −25.46±1.44 | −12.4 (−15.5, −9.4) p<0.001 | −10.3 (−13.4, −7.3) p<0.001 |

*AUCn min/n—baseline urges-to-smoke score (mm).

AUC, area under the urges-to-smoke-vs.-time curve

To aid interpretation of the study findings model-based estimates of treatment differences in mean average score changes were presented together with CIs instead of, and equivalently to, model-based estimates of treatment differences in mean AUCs. The average urges-to-smoke change from baseline was defined as

where n was the endpoint of the time interval.

As the study included two different treatment comparisons (mouth spray 2 mg vs either 2 or 4 mg lozenge), the significance level for the relevant test was adjusted to 2.5% to ensure that the overall type-I error rate was no greater than 5%.

To evaluate the primary study objective and to avoid inflation of the significance level due to multiple testing, for each strength of the reference product (2 or 4 mg lozenge), the statistical evaluation of the primary endpoints was performed in a hierarchical order, starting with the 5-min evaluation. Thus, no additional multiplicity adjustments were needed, that is, all statistical tests relating to evaluation of the primary endpoints were performed at the 2.5% significance level.

To correct for bias due to the discrete sampling scheme, the times to 25%, 50%, 75% and 90% reduction of baseline urges-to-smoke scores were estimated from the assessments up to 120 min postadministration using linear interpolation between assessment time points. Any time-to-event that exceeded 120 min was censored at that time point. Estimated medians of time-to-event and corresponding 95% CIs were calculated by treatment. Pair-wise treatment comparisons of the times to 25%, 50%, 75% and 90% reduction of baseline urges-to-smoke scores were based on the Sign test.

The proportion of subjects who attained 25%, 50%, 75% and 90% reduction of baseline urges to smoke within 1, 3, 5 and 10 min, respectively, were pair-wise compared between nicotine mouth spray and the two comparator lozenges by using the McNemar test for each time point.

All statistical tests relating to evaluation of the primary endpoints were two-sided with a significance level α=2.5%. Corresponding CIs were two-sided and had a nominal confidence level of 97.5%. All other statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level α=5%. Corresponding interval estimates were two-sided and had a nominal confidence level of 95%.

Results

Study population

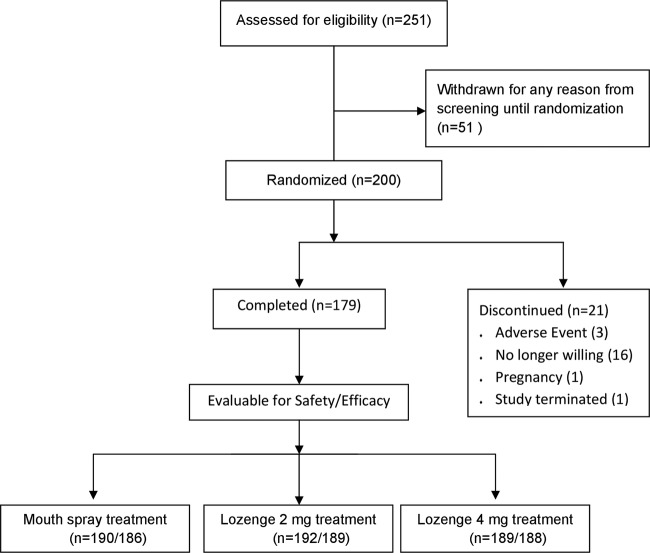

Of 251 subjects who were screened for entry, 200 subjects (105 men and 95 women) were randomised to treatment (figure 1). The mean age of the study subjects was 32.9 (SD 11.4, range 19–55) years. The subjects smoked an average of 17.7 (SD=4.8, range 10–50) cigarettes/day, and had smoked for a mean of 16.8 (SD=11.5, range 1–45) years. All subjects smoked their first cigarette of the day within 30 min of waking. All 199 subjects with evaluable data for at least one endpoint and one treatment were included in the analysis set. Valid efficacy data from all treatments were provided by 178 subjects.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the progress of subjects through the phases of the study.

Changes in urges to smoke

During the first 10 min after start of administration, use of mouth spray resulted in greater reductions in craving than use of either 2 or 4 mg lozenge (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean urges-to-smoke-versus-time curve during 120 min postadministration. Note change in scale from 5 min onwards.

The estimated mean differences in average urges-to-smoke score change from baseline, AUCn min/n−baseline urges-to-smoke score, between mouth spray 2 mg and either 2 or 4 mg lozenges during the first 1, 3, 5 and 10 min were all statistically significant (table 1).

The corresponding post hoc sensitivity analysis restricted to the 178 subjects who completed all treatments and had valid data for all three treatments showed only minor numerical deviations in estimates and did not change the statistical hypothesis evaluations (data not shown). Although evaluation of morning data was not part of the prespecified analyses, differences in average urges-to-smoke change from baseline based on urges-to-smoke ratings from treatments given in the morning were of the same order of magnitude as the afternoon differences, both numerically and with respect to statistical significance (data not shown).

The distributions of the estimated times to a perceived 25%, 50% and 75%, relief of craving were in each case statistically significantly different (p<0.001) between mouth spray and lozenge 2 or 4 mg (90% relief p<0.006), and a larger estimated proportion of subjects perceived a given degree of craving relief with mouth spray than with either lozenge 2 mg or lozenge 4 mg within each time point during the first 30 min. The estimated time from start of nicotine administration until half of users experienced a reduction in craving of at least 25% was 1.19 min (95% CI 0.66 to 1.73) for nicotine mouth spray, compared to 3.76 (3.15 to 4.41) and 3.49 (3.00 to 3.93) minutes for nicotine lozenge 2 and 4 mg, respectively. Corresponding values for 50% reduction in craving were 3.40 (2.42 to 4.53) minutes versus 9.92 (7.06 to 14.35) and 9.20 (6.09 to 12.35) minutes, respectively.

A statistical comparison of the proportions of subjects who attained 25%, 50%, 75% and 90% reductions in craving score compared to baseline within 1, 3, 5 and 10 min, respectively, further supported the overall differences found. For comparisons against both the lozenges, there were statistically significant differences at the 5% level favouring mouth spray 2 mg for all degrees of reduction and at all four assessment time points, with the exception of the comparison against lozenge 4 mg at 10 min with respect to 25% reduction (p=0.058).

In summary, the onset of relief of urges to smoke was substantially faster following use of 2 mg nicotine mouth spray compared to the 2 and 4 mg nicotine lozenge.

Adverse events

A total of 414 treatment-emergent adverse events were reported during the study. Of these, 340 adverse events were classified as possibly related to one of the study treatments, with 183, 68 and 89 adverse events possibly related to mouth spray 2 mg, lozenge 2 mg and lozenge 4 mg, respectively. The types of adverse event reported with the mouth spray were similar to those reported with the lozenge, and no unexpected adverse events occurred with the spray. The majority of treatment-related adverse events were either mild (74%) or moderate (25%). Overall, the most common adverse events for mouth spray 2 mg, lozenge 2 mg and lozenge 4 mg (number of subjects reporting) were hiccups (29, 2, 6), nausea (29, 4, 15), throat irritation (21, 11, 13), dyspepsia (18, 4, 9) and salivary hypersecretion (9, 1, 2).

Discussion

In this study of smokers who had been abstinent for more than 12 h, nicotine mouth spray 2 mg relieved urges to smoke significantly faster than either nicotine lozenge 2 or 4 mg. Our results reflect the findings of an earlier study of another nicotine mouth spray (Zonnic, NicoNovum, Helsingborg, Sweden), which reduced craving after overnight abstinence significantly faster than nicotine 2 mg gum.3

One plausible explanation for the faster relief of urges to smoke with the mouth spray is speed of nicotine absorption. Earlier findings showed that the mouth spray delivers nicotine into the blood stream faster than the lozenge.5 If speed of nicotine absorption is the main factor that underpins these differences, one could reason that because the speed of absorption of nicotine from the lozenge is similar to that from other currently available oral NRT formulations, such as nicotine chewing gum,8 it is likely that the mouth spray will also surpass the other oral NRT products in terms of speed of craving relief.

Although focus of this study was on the immediate effects of the study treatments on urges to smoke, measurements were made up to 2 h after administration. It appears from figure 2 as if not only the start but also the decline of relief from urges to smoke occurred faster with mouth spray than with lozenges. This observation is paralleled by not only a faster absorption of nicotine from mouth spray than lozenge but also a faster decline of plasma nicotine concentrations.5

The nicotine mouth spray provides a strong sensory stimulation, given the instant availability of the dose on the oral mucosa, which may enhance the speed of onset of craving relief. This study investigated and compared the total effect on craving relief, which is the outcome most relevant from a clinical perspective, of the nicotine mouth spray and nicotine lozenge 2 and 4 mg. However, contributions from pharmacological effects and sensory stimuli cannot be separated based on our results.

Our trial used an active comparator but did not include a placebo arm, and participant allocation could not be blinded. In addition to speed of absorption and sensory effects, the novelty of the mouth spray, distraction due to its mode of administration and participant and staff expectations could conceivably have impacted on the study results. An effort was made to mitigate against possible novelty effects by familiarising participants with the spray in the morning of the experimental session. Nevertheless, previous findings that nicotine is absorbed faster from the mouth spray than the lozenge5 provides a rationale for considering the faster relief of craving to be a clinically reproducible effect, rather than a by-product of expectations.

No unexpected adverse events were observed in this study. We do not expect that nicotine administered as a mouth spray will be associated with any new types of side effects. In the current study, local irritation and gastrointestinal effects were more frequent with mouth spray than with lozenges, but it should be noted that most reports of adverse events were elicited by scheduled questioning. In a recent clinical trial comparing the nicotine mouth spray with placebo,6 hiccups, throat irritation, nausea, dyspepsia, mouth irritation, salivary hypersecretion, burning sensation in mouth and constipation were the more common in the nicotine group, but the ratings of acceptability of the nicotine mouth spray were good and only 9.1% of subjects on active spray withdrew owing to adverse events, compared to 7.5% on placebo. It remains to be seen whether any local and gastrointestinal effects will affect clinical use of the spray.

Conclusions

Nicotine mouth spray provides fast relief of craving and has clear potential as a treatment for smoking cessation. The current trial adds to the existing evidence that nicotine replacement products with faster nicotine delivery provide more effective relief of urges to smoke. The mouth spray represents an important new development in extending the range of nicotine replacement treatments, and may potentially also improve their efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study manager Paola Lefèvre, the study team at McNeil AB, and Anne Hendrie who edited the paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: The current study was designed and performed jointly by all four authors of this article. HK acted as principal investigator. Data analyses were performed by RP. The manuscript was written, reviewed, revised and approved by all named authors.

Funding: This study was funded by McNeil AB, Helsingborg, Sweden, who manufacture nicotine mouth spray (Nicorette Mouth Spray 1 mg/spray).

Competing interests: AH, RP and HK are employees of McNeil AB, Sweden. Peter Hajek has received research funding from and provided consultancy to several manufacturers of stop-smoking medications.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval : The Medical Products Agency, Sweden and the Independent Ethics Committee, Lund, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, et al. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation (review). Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2008; (1): CD000146 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shahab L, McEwen A, West R. Acceptability and effectiveness for withdrawal symptom relief of a novel oral nicotine delivery device: a randomised crossover trial. Psychopharmacology 2011;216:187–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McRobbie H, Thornley S, Bullen C, et al. A randomized trial of the effects of two novel nicotine replacement therapies on tobacco withdrawal symptoms and user satisfaction. Addiction 2010;105:1290–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, et al. Temporal effects of nicotine nasal spray and gum on nicotine withdrawal symptoms. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1998;140:98–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kraiczi H, Hansson A, Perfekt R. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of nicotine with a novel mouth spray form of nicotine replacement therapy. Nic Tob Res 2011;13:1176–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonnesen P, Lauri H, Perfekt R, et al. Efficacy of a nicotine mouth spray in smoking cessation: a randomised, double blind trial. Eur Respir J 2012;40:548–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiffman S, Dresler CM, Hajek P, et al. Efficacy of a nicotine lozenge for smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1267–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi JH, Dresler CM, Norton MR, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a polacrilex lozenge. Nic Tob Res 2003;5:635–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.