Abstract

Objective

To assess whether bed bug infestation was linked to sleep disturbances and symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Design

Exploratory cross-sectional study.

Setting

Convenience sample of tenants recruited in apartment complexes from Montreal, Canada.

Participants

39 bed bug-exposed tenants were compared with 52 unexposed tenants.

Main outcome measures

The effect of bed bug-exposed tenants on sleep disturbances, anxiety and depression symptoms measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, 5th subscale, Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale and Patient Health Questionnaire, 9-item, respectively.

Results

In adjusted models, bed bug infestation was strongly associated with measured anxiety symptoms (OR (95% CI)=4.8 (1.5 to 14.7)) and sleep disturbance (OR (95% CI)=5.0 (1.3–18.8)). There was a trend to report more symptoms of depression in the bed bug-infested group, although this finding was not statistically significant ((OR (95% CI)=2.5(0.8 to 7.3)).

Conclusions

These results suggest that individuals exposed to bed bug infestations are at risk of experiencing sleep disturbance and of developing symptoms of anxiety and possibly depression. Greater clinical awareness of this problem is needed in order for patients to receive appropriate mental healthcare. These findings highlight the need for undertaking of deeper inquiry, as well as greater collaboration between medical professionals, public health and community stakeholders.

ARTICLE SUMMARY.

Article focus

Infestations with the common bed bug (Cimex lectularius L.) have become problematic in many cities.

No epidemiological studies currently exist on the mental health impacts of bed bug infestations.

In this exploratory cross-sectional analysis, we assessed whether bed bug infestations were linked to sleep disturbances and symptoms of anxiety and depression among tenants in Montreal, Quebec.

Key messages

This study suggests that individuals exposed to bed bugs may be at risk of experiencing sleep disturbance and of developing anxious and possibly depressive symptoms.

Appropriate control of bed bug is required to manage the situation and its potential health impacts.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The convenience sample presents a risk for selection bias.

There is a possibility of misclassification biases due to self-report even though the Cronbach α values calculated from our data showed remarkable consistency with literature values for the original instruments.

These results are cross-sectional in nature and follow-up studies are required.

Introduction

Adult bed bugs are 4–6 mm long, oval and flattened insects that feed on human blood. Feeding sessions typically last 15 min and are followed by the departure of the bug towards its harbourage site. Once fed, bed bugs do not remain attached to their prey.1 Bed bug bites, like mosquito bites are associated with local cutaneous allergic reactions.2 To date, there have been no reports of infectious disease transmission via bed bug bites.2 3 Bed bugs can be exterminated rapidly but extermination techniques are complex. In some settings bed bug infestation may become chronic.4

Anecdotal and historical evidence suggests that infestation by the common bed bug (Cimex lectularius L.) may be a stressor that has an emotional and psychological effect.3 Field workers and pest control managers in Montreal,5 Toronto4 and in 43 countries around the globe surveyed by the National Pest Management Association have observed psychological distress among individuals living with infestation.6 There are reports of people resorting to dangerous methods in order to rid their dwellings of bed bugs.7 Recently, Goddard and de Shazo8 noted that comments posted on bed bug-related websites revealed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. None of these studies, however, were performed in a clinical setting and there are currently no original published epidemiological data available on the mental health impact of bed bug infestation. The objective of this study was to conduct an exploratory cross-sectional analysis comparing individuals living with and without bed bug infestations using three standardised clinical mental health measures.

Methods

Data collection and measures

Unfit housing conditions due to water infiltration, mould and vermin infestation are frequently reported to the Montreal Public Health Department (MPH). Decision to intervene in such situations is taken by the environmental health team that includes physicians and an experienced hygienist. The aim of field intervention, when mandated, is to produce recommendations for remediation of the buildings involved and to ensure healthcare for tenants who may require attention. However, relocation of tenants to other housing complexes is only recommended in cases where tenants experience a significant negative health impact due to water infiltration. Participants were recruited from the two Montreal apartment complexes who were subject to public health interventions targeting unfit housing conditions led by the MPH Department and their community partners between January and June 2010. This cross-sectional study is based on data provided by a convenience sample of 91 tenants recruited. All participants agreed to allow the data they provided to be used for research purposes.

Physicians and nurses familiar with unfit housing conditions and infestations collected all data. Culturally and linguistically competent translators were available and all questionnaire material was available in English, French and Spanish. Ethical approval was provided by the research ethics committee of the Montreal Agency for Health and Social Services. The research has conformed to the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki.

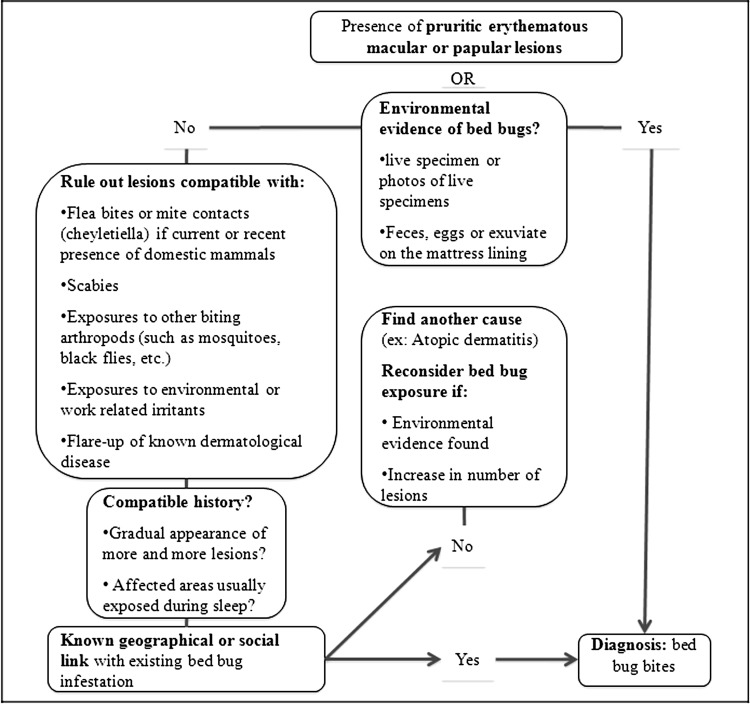

Data were obtained from an intervention health questionnaire. Symptoms of depression and anxiety were evaluated using the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9)9 and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7)10 which are based on criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV and DSM-IV-TR, respectively. Sleep disturbances were measured using questions 1–8 (5th subscale) of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.11 Bed bug exposure status was initially determined by self-report; participants were asked to point to the culprit insect on an identification tool containing pictures of bed bugs and other commonly found insects in Montreal apartment buildings. Details related to infestation (onset, corrective measures taken) were recorded. This subjective evidence was supported by objective dermatological and/or environmental evidence of infestation when available (figure 1). Individuals with past bed bug exposure—but who reported that bed bugs had not been seen in the dwelling for >30 days—were classified as unexposed (figure 2). Other variables from the health questionnaire include demographic features, history of chronic medical and psychiatric conditions (>6 months in duration), experience of a particularly stressful event within the last year (yes/no variable) as well as environmental exposure information other than that pertaining to bed bugs (number of inhabitants, exposure to cockroaches).

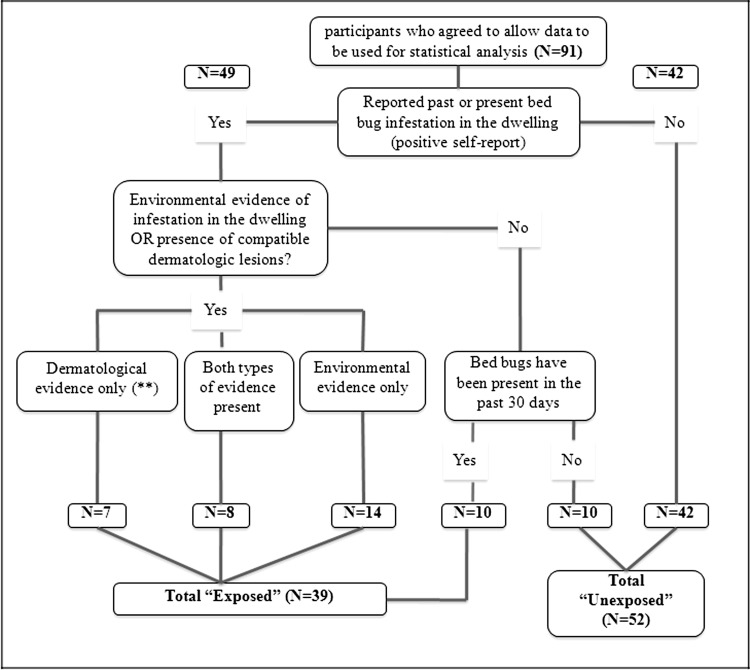

Figure 1.

Algorithm for attribution of a diagnosis of bed bug infestation based on the presence of characteristic lesions and environmental evidence.

Figure 2.

Participant flowchart.

Statistical analysis

The χ² analyses were used to distinguish characteristics particular to the bed bug-exposed group as compared with the unexposed group. Scores for the three instruments were dichotomised into ‘present/absent’. Scores corresponding to symptoms ‘present’ were: 10 and over on the PHQ-9 of 27, (moderate symptoms of depression or worse), 5 and over on the GAD-7 of 21(mild symptoms of anxiety or worse) and 10 and over 27 on the PSQI 5th subscale. For any given participant, data from the GAD-7 or PHQ-9 were disregarded if three or more items were left blank. Missing values for these scales were replaced with the mean scores of the other subjects’ items response if the number of missing responses was less than 3.

Multivariable logistic regression was used to calculate OR and 95% CI for an association between bed bug infestation exposure and anxiety, depressive symptoms and sleep disturbance. Models were initially run for exposure status alone, then adjusted for sex and age. The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 models were adjusted as well for psychiatric diagnosis and number of inhabitants. The GAD-7 model was additionally adjusted for cockroaches in the dwelling. Adjusted model parameters did not change by more than 10% with the addition of employment status, perceived sufficient means, civil status, medical diagnoses or experience of a stressful event within the last year. Final models were rerun without 10 individuals for whom there were no objective evidence to support or refute their (previous) self-report. Cronbach α values were calculated to measure the internal consistency of the psychometric tools (GAD-7, PHQ-9 and PSQI(5)). Analyses were performed using SPSS V.12.0.2 for Windows (SPSS 1989–2003).

Results

There were 39 individuals exposed to bed bugs and 52 unexposed individuals (figure 2). Exposed and unexposed individuals were found in both housing complexes. Individuals exposed to bed bug infestation did not differ significantly from those unexposed on the characteristics shown in table 1 except for ‘number of individuals living in the dwelling’ and ‘self-reported cockroach exposure’. Pearson χ² scores for the univariate associations between bed bug infestation status and the dependent variables were significant at p<0.05 for the GAD-7 and PSQI(5), but not for the PHQ-9.

Table 1.

Characteristics and instrument scores of participants according to bed bug infestation exposure status

| Characteristics | Exposed to bed bug infestation (%) | N* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 50 | 38 | ||

| Female | 38 | 53 | ||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤36 | 48 | 48 | ||

| ≥37 | 37 | 43 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 41 | 17 | ||

| High school or more | 38 | 60 | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 42 | 36 | ||

| Unemployed | 44 | 55 | ||

| Legally married | ||||

| Yes | 42 | 50 | ||

| No | 44 | 41 | ||

| Perceived sufficient means | ||||

| Yes | 46 | 39 | ||

| No | 42 | 48 | ||

| Stressful event in last year | ||||

| Yes | 43 | 58 | ||

| No | 42 | 33 | ||

| Psychiatric diagnosis | ||||

| None | 43 | 76 | ||

| 1+ | 44 | 9 | ||

| Medical diagnosis | ||||

| None | 53 | 40 | ||

| 1+ | 35 | 51 | ||

| Number of inhabitants† | ||||

| 1–2 | 20 | 25 | ||

| 3+ | 52 | 65 | ||

| Cockroaches in dwelling† | ||||

| Present | 50 | 72 | ||

| Absent | 16 | 19 | ||

| Anxiety symptoms (GAD-7)† | ||||

| Present | 55 | 31 | ||

| Absent | 32 | 56 | ||

| Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) | ||||

| Present | 52 | 27 | ||

| Absent | 37 | 60 | ||

| Sleep disturbance (PSQI(5))† | ||||

| Present | 71 | 14 | ||

| Absent | 40 | 68 | ||

| Total | 91 | |||

*May not total due to missing data.

†These variables differed significantly for the exposure groups on Pearson χ² analysis p<0.05, two-sided test.

GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; PHQ-9, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, 5th subscale; PSQI(5), Patient Health Questionnaire, 9-item.

Results of the logistic regression models are displayed in table 2. In both unadjusted and adjusted models, the association between anxiety symtoms and bed bug infestation status was statistically significant (OR (95% CI) adjusted model=4.8 (1.5 to 14.7)). A statistically significant association was also found for sleep disturbance (OR (95% CI) adjusted model=5.0 (1.3 to 18.8)). There was a statistically non-significant association observed between depressive symptoms and bed bug infestation (OR (95% CI) adjusted model=2.5 (0.8 to 7.3)). Sensitivity analysis as outlined above did not alter results.

Table 2.

ORs and 95% CIs for the associations between bed bug infestation exposure and mental health symptoms

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Fully adjusted OR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|

| PSQI(5) | 3.80 (1.10 to 13.35) | 5.00 (1.30 to 18.80) |

| GAD-7 | 2.56 (1.04 to 6.32) | 4.75 (1.54 to 14.70) |

| PHQ-9 | 1.86 (0.74 to 4.67) | 2.48 (0.84 to 7.30) |

*All models were adjusted for sex and age. Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, 5th subscale (PHQ-9) were further adjusted for psychiatric diagnosis and number of inhabitants. GAD-7 was additionally adjusted for cockroaches in dwelling.

PSQI(5), Patient Health Questionnaire, 9-item.

The Cronbach α values calculated from the data for the GAD-7, PHQ-9 and PSQI(5) were found to be 0.86, 0.83 and 0.69, respectively.

Discussion

Our study showed that anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbances were significantly more likely to occur among individuals exposed to bed bug infestation. The association between exposure and depressive symptoms occurred in the expected direction, but was non-significant at the level of p<0.05.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to quantitatively explore the anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms and sleep disturbance associated with bed bug infestations. Literature on anxiety and depressive symptoms and sleep disturbance associated with infestation with biting arthropods is scant, but some anecdotal evidence exists that infestation with pigeon fleas12 and head lice can have a negative effect on sleep.13 The dermatologic literature details other pruritic skin conditions such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis and their consequences on sleep14 and mental health.15

This study has several limitations. The convenience sample presents a risk for selection bias, the magnitude of which is attenuated by the fact that both exposed and non-exposed subjects lived in the same apartment complexes. There is a possibility of misclassification due to self-report in the intervention context. However, the Cronbach α values calculated from the totality of our data showed remarkable consistency with literature values for the original instruments. Cronbach α values in our study for the GAD-7, PHQ-9 and PSQI(5) were 0.86, 0.83 and 0.69, respectively, with corresponding literature values of 0.92,10 0.86–0.899 and 0.70–0.78,16 respectively.

These results are cross-sectional in nature and follow-up studies are required. A ‘prepost’ intervention approach would be appropriate in this situation as there is an ethical imperative to treat the dwellings of patients in addition to their symptoms. Such an approach would allow us to evaluate changes in reported symptoms after the bed bugs have been eradicated in the dwelling and the stressor thus removed.

Clinicians should be aware of the impacts bed bug infestations can have on patients, particularly those from vulnerable populations. Rapid implementation of policies to control the infestation based on evidence-based removal and prevention practices will be required to manage the situation and its potential societal impacts. This is a considerable task, and one could envision success if a multidisciplinary approach is used with collaboration between municipal authorities, medical professionals, public health, entomologists and community stakeholders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Michael Potter and Jerome Goddard revised the article and gave relevant comments regarding manuscript preparation. Benoît Côté and Jérome Coulombe, both dermatologists practicing in Montreal gave helpful comments on the content of figure 1. Isabelle Mondou gave comments on the study and the manuscript. Nassima Chirane offered comments on the study. Valérie Clayman helped to edit the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors : All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors accept responsibility for the content of this manuscript. The article is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. The authors reviewed this manuscript and all agree that the work is ready for submission. The study was conceptualised and designed by SRS, SP, MF, LJ, GD and PR. The data were acquired by SRS, SP, LJ and GD. Statistical analysis was performed by SRS, SP and MF. The data were analysed and interpreted by all authors. The manuscript was drafted by SRS and revised by all authors.

Funding : The work presented in this manuscript was supported financially by the Direction de santé publique de Montréal.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Comité d’éthique de la recherche Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Usinger R. Monograph of Cimicidae. Thomas Say Foundation, volume 7, 1966, College Park, MD: Entomological Society of America [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goddard J, de Shazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA 2009;301:1358–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delaunay P, Blanc V, Del Giudice P, et al. Bedbugs and infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:200–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald L, Zavys R. Bed bugs are back Are we ready? 2009. http://www.woodgreen.org (accessed 21 Dec 2011).

- 5.Perron S, King N, Lajoie L, Jacques L. Les punaises de lit, retour vers le futur. Bulletin d'information en santé environnementale. http://www.inspq.qc.ca/bise/post/Les-punaises-de-lit-retour-vers-le-futur.aspx (accessed 25 Jan 2010)

- 6.Potter M, Rosenberg B, Henriksen M. Bugs without borders-executive summary: defining the global bed bug resurgence. http://www.pestworld.com (accessed 21 Dec 2011).

- 7.Manuel J. Invasion of the bedbugs. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118:A429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goddard J, de Shazo R. Psychological effects of bedbug attacks (Cimex lectulairus L.). Am J Med 2012;125:101–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haag-Wackernagel D, Spiewak R. Human infestation by pigeon fleas (Ceratophyllus columbae) from feral pigeons. Ann Agric Environ Med 2004;11:343–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva L, Alencar R de A, Madeira NG. Survey assessment of parental perceptions regarding head lice. Int J Dermatol 2008;47:249–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bender BG, Leung SB, Leung DYM. Actigraphy assessment of sleep disturbance in patients with atopic dermatitis: an objective life quality measure. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;111:598–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong J, Koo B, Koo J. The psychosocial and occupational impact of chronic skin disease. Dermatol Ther 2008;21:54–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. J Psychosom Res 1998;45:5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.