Abstract

Impaction of maxillary and mandibular canines is a frequently encountered clinical problem, the treatment of which usually requires an interdisciplinary approach. Surgical exposure of the impacted tooth and the complex orthodontic mechanisms that are applied to align the tooth into the arch may lead to varying amounts of damage to the supporting structures of the tooth, not to mention the long treatment duration and the financial burden to the patient. Hence, it seems worthwhile to focus on the means of early diagnosis and interception of this clinical situation. In the present article, an overview of the incidence and sequelae, as well as the surgical, periodontal, and orthodontic considerations in the management of impacted canines is presented.

KEY WORDS: Diagnosis, etiology, impacted canines, orthodontic techniques, prevention, surgical techniques

The orthodontic treatment of impacted maxillary canine remains a challenge to today's clinicians. The treatment of this clinical entity usually involves surgical exposure of the impacted tooth, followed by orthodontic traction to guide and align it into the dental arch. Bone loss, root resorption, and gingival recession around the treated teeth are some of the most common complications.

Early diagnosis and intervention could save the time, expense, and more complex treatment in the permanent dentition. Tooth impaction can be defined as the infraosseous position of the tooth after the expected time of eruption, whereas the anomalous infraosseous position of the canine before the expected time of eruption can be defined as a displacement. Most of the time, palatal displacement of the maxillary canine results in impaction.[1,2]

With early detection, timely interception and well-managed surgical and orthodontic treatment, impacted maxillary canines can be allowed to erupt and be guided to an appropriate location in the dental arch. However, it is only with interdisciplinary care of general dentists and specialists that impacted maxillary canines can be treated successfully.

Prevalence and Etiology

Maxillary canines are the most commonly impacted teeth, second only to third molars.[2] Maxillary canine impaction occurs in approximately 2% of the population and is twice as common in females as it is in males. The incidence of canine impaction in the maxilla is more than twice that in the mandible. Of all patients who have impacted maxillary canines, 8% have bilateral impactions.[3] Approximately one-third of impacted maxillary canines are located labially and two-thirds are located palatally.[4,5] Canine impaction can be caused by various factors. The exact etiology of palatally displaced maxillary canines is unknown. The results of Jacoby's[6] study showed that 85% of palatally impacted canines had sufficient space for eruption, whereas only 17% of labially impacted canines had sufficient space. Therefore, arch length discrepancy is thought to be a primary etiologic factor for labially impacted canines.[5] Several etiologic factors for canine impactions have been proposed: localized, systemic, or genetic [Box 1].[1]

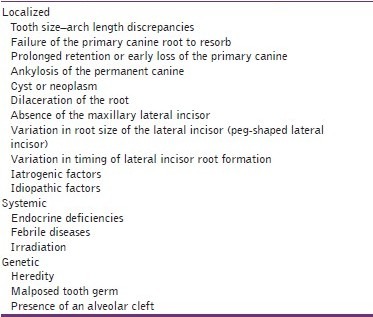

Box 1.

Etiologic factors – associated with impacted canines

Two major theories associated with palatally displaced maxillary canines are the guidance theory and genetic theory.[7] The guidance theory proposes that the canine erupts along the root of the lateral incisor, which serves as a guide, and if the root of the lateral incisor is absent or malformed, the canine will not erupt.[8]

The genetic theory points to genetic factors as a primary origin of palatally displaced maxillary canines and includes other possibly associated dental anomalies, such as missing or small lateral incisors.[9] Baccetti[10] reported that palatally impacted maxillary canines are genetically reciprocally associated with anomalies such as enamel hypoplasia, infraocclusion of primary molars, aplasia of second premolars, and small maxillary lateral incisors.

Sequelae of Canine Impaction

Shafer et al.[11] suggested the following sequelae for canine impaction:

Labial or lingual malpositioning of the impacted tooth,

Migration of the neighboring teeth and loss of arch length,

Internal resorption,

Dentigerous cyst formation,

External root resorption of the impacted tooth, as well as the neighboring teeth,

Infection particularly with partial eruption, and

Referred pain and combinations of the above sequelae.

It is estimated that in 0.71% of children in the 10–13 year age group, permanent incisors have resorbed because of the ectopic eruption of maxillary canines.[12] On the other hand, the presence of the impacted canine may cause no untoward effects during the lifetime of the person.

These potential complications, as well as others that will be detailed later, emphasize the need for close observation of the development and eruption of these teeth during “routine” periodic dental examination of the growing child.

Diagnosis of Canine Impaction

The diagnosis of canine impaction is based on both clinical and radiographic examinations.

Clinical Evaluation

It has been suggested that the following clinical signs might be indicative of canine impaction:[3]

Delayed eruption of the permanent canine or prolonged retention of the deciduous canine beyond 14–15 years of age,

Absence of a normal labial canine bulge,

Presence of a palatal bulge, and

Delayed eruption, distal tipping, or migration (splaying) of the lateral incisor.

According to Ericson and Kurol,[12] the absence of the “canine bulge” at earlier ages should not be considered as indicative of canine impaction. In their evaluation of 505 schoolchildren between 10 and 12 years of age, they found that 29% of the children had nonpalpable canines at 10 years, but only 5% had it at 11 years, whereas at later ages only 3% had nonpalpable canines. Therefore, for an accurate diagnosis, the clinical examination should be supplemented with a radiographic evaluation.

Radiographic Evaluation

Although various radiographic exposures including occlusal films, panoramic views, and lateral cephalograms can help in evaluating the position of the canines, in most cases, periapical films are uniquely reliable for that purpose.[3,13]

Periapical films

A single periapical film provides the clinician with a two-dimensional representation of the dentition. In other words, it would relate the canine to the neighboring teeth both mesiodistally and superoinferiorly. To evaluate the position of the canine buccolingually, a second periapical film should be obtained by one of the following methods.

Tube-shift technique or Clark's rule or (SLOB) rule

Two periapical films are taken of the same area, with the horizontal angulation of the cone changed when the second film is taken. If the object in question moves in the same direction as the cone, it is lingually positioned. If the object moves in the opposite direction, it is situated closer to the source of radiation and is therefore buccally located.

Buccal-object rule

If the vertical angulation of the cone is changed by approximately 20° in two successive periapical films, the buccal object will move in the direction opposite to the source of radiation. On the other hand, the lingual object will move in the same direction as the source of radiation. The basic principle of this technique deals with the foreshortening and elongation of the images of the films.

Occlusal films

Also help to determine the buccolingual position of the impacted canine in conjunction with the periapical films, provided that the image of the impacted canine is not superimposed on the other teeth.

Extraoral films

Frontal and lateral cephalograms

These can sometimes aid in the determination of the position of the impacted canine, particularly its relationship to other facial structures (e.g., the maxillary sinus and the floor of the nose).

Panoramic films

These are also used to localize impacted teeth in all three planes of space, as much the same as with two periapical films in the tube-shift method, with the understanding that the source of radiation comes from behind the patient; thus, the movements are reversed for position.

CT/CBCT

Clinicians can localize canines by using advanced three-dimensional imaging techniques. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) can identify and locate the position of impacted canines accurately. By using this imaging technique, dentists also can assess any damage to the roots of adjacent teeth and the amount of bone surrounding each tooth. However, increased cost, time, radiation exposure, and medicolegal issues associated with using CBCT limit its routine use.

The proper localization of the impacted tooth plays a crucial role in determining the feasibility of as well as the proper access for the surgical approach and the proper direction for the application of orthodontic forces.

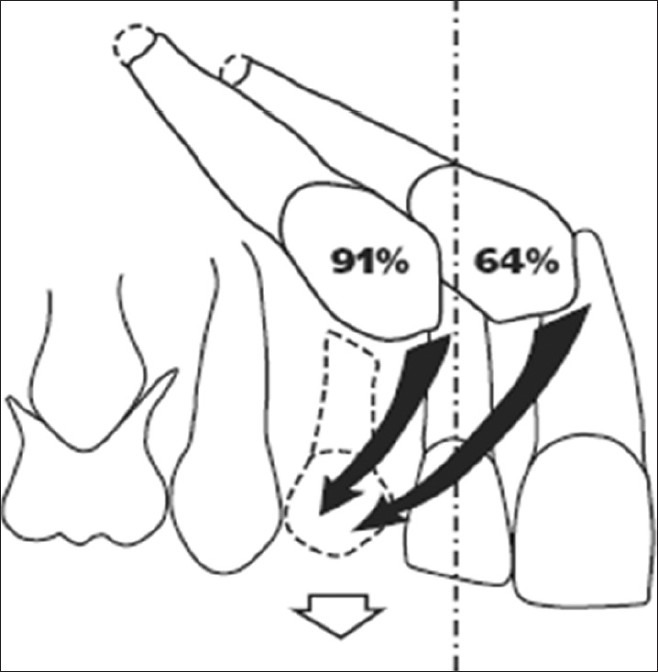

Interceptive Treatment

When the clinician detects early signs of ectopic eruption of the canines, an attempt should be made to prevent their impaction and its potential sequelae. Selective extraction of the deciduous canines as early as 8 or 9 years of age has been suggested by Williams as an interceptive approach to canine impaction in Class I uncrowded cases. Ericson and Kurol[12] suggested that removal of the deciduous canine before the age of 11 years will normalize the position of the ectopically erupting permanent canines in 91% of the cases if the canine crown is distal to the midline of the lateral incisor. On the other hand, the success rate is only 64% if the canine crown is mesial to the midline of the lateral incisor [Figure 1].[12]

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration showing the normalization rates of the maxillary canine after extraction of the primary canine when the permanent maxillary canine is located mesially and distally to the midline of the lateral incisor

Treatment alternatives

Each patient with an impacted canine must undergo a comprehensive evaluation of the malocclusion. The clinician should then consider the various treatment options available for the patient, including the following:[3]

No treatment if the patient does not desire it. In such a case, the clinician should periodically evaluate the impacted tooth for any pathologic changes. It should be remembered that the long-term prognosis for retaining the deciduous canine is poor, regardless of its present root length and the esthetic acceptability of its crown. This is because, in most cases, the root will eventually resorb and the deciduous canine will have to be extracted.

Autotransplantation of the canine.

Extraction of the impacted canine and movement of a first premolar in its position.

Extraction of the canine and posterior segmental osteotomy to move the buccal segment mesially to close the residual space.

Prosthetic replacement of the canine.

Surgical exposure of the canine and orthodontic treatment to bring the tooth into the line of occlusion. This is obviously the most desirable approach.

When to Extract an Impacted Canine

It should be emphasized that extraction of the labially erupting and crowded canine, unsightly as this tooth may look, is contraindicated. Such an extraction might temporarily improve the esthetics, but may complicate and compromise the orthodontic treatment results, including the ability to provide the patient with a functional occlusion. The extraction of the canine, although seldom considered, might be a workable option in the following situations:[3]

If it is ankylosed and cannot be transplanted,

If it is undergoing external or internal root resorption,

If its root is severely dilacerated,

If the impaction is severe (e.g., the canine is lodged between the roots of the central and lateral incisors and orthodontic movement will jeopardize these teeth),

If the occlusion is acceptable, with the first premolar in the position of the canine and with an otherwise functional occlusion with well-aligned teeth,

If there are pathologic changes (e.g., cystic formation, infection), and

If the patient does not desire orthodontic treatment.

Management of Impacted Canines

The most desirable approach for managing impacted maxillary canines is early diagnosis and interception of potential impaction. However, in the absence of prevention, clinicians should consider orthodontic treatment followed by surgical exposure of the canine to bring it into occlusion. In such a case, open communication between the orthodontist and oral surgeon is essential, as it will allow for the appropriate surgical and orthodontic techniques to be used.

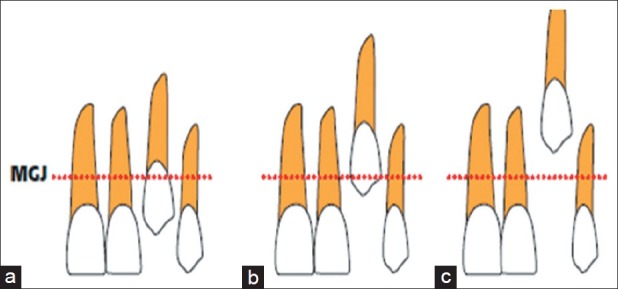

The most common methods used to bring palatally impacted canines into occlusion are surgically exposing the teeth and allowing them to erupt naturally during early or late mixed dentition and surgically exposing the teeth and placing a bonded attachment to and using orthodontic forces to move the tooth.[14] Kokich[15] reported three methods for uncovering a labially impacted maxillary canine: gingivectomy, creating an apically positioned flap, and using closed eruption techniques [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Recommended surgical techniques relative to the mucogingival junction (MGJ) when the canine cusp is (a) coronal to the MGJ: gingivectomy; (b) apical to the MGJ: creating an apically positioned flap; and (c) significantly apical to the MGJ: using a closed eruption technique

Orthodontists have recommended that other clinicians first create adequate space in the dental arch to accommodate the impacted canine and then surgically expose the tooth to give them access so that they can apply mechanical force to erupt the tooth. Although various methods work, an efficient way to make impacted canines erupt is to use closed-coil springs with eyelets, as long as no obstacles impede the path of the canine.

If the canine is in close proximity to the incisor roots and a buccally directed force is applied, it will contact the roots and may cause damage. In addition, the canine position may not improve due to the root obstacle. Consequently, various techniques have been proposed that involve moving the impacted tooth in an occlusal and posterior direction first and then moving it buccally into the desired position. When using a bonded attachment and orthodontic forces to bring the impacted canines into occlusion, it is important to remember that first premolars should not be extracted until a successful attempt is made to move the canines. If the attempt is unsuccessful, the permanent canines should be extracted.

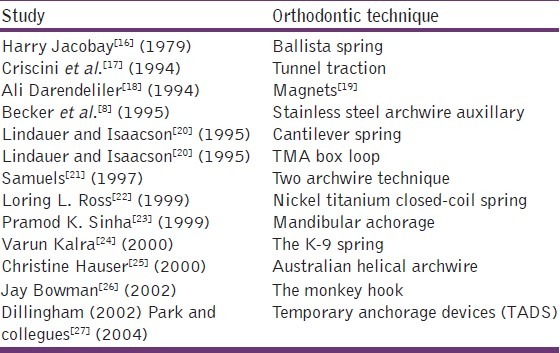

A summary of orthodontic techniques used to manage impacted canines is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summary of orthodontic techniques used to manage impacted canines

In such cases, the orthodontist has to decide if the premolar should be moved into the canine position. Orthodontists should consider treatment alternatives, such as autotransplantation or restoration, in collaboration with other specialists, including oral surgeons, periodontists, and prosthodontists. The patient should be informed about all of the potential complications before surgical and orthodontic interventions take place.

Conclusion

The management of impacted canines is important in terms of esthetics and function. Clinicians must formulate treatment plans that are in the best interest of the patient and they must be knowledgeable about the variety of treatment options. When patients are evaluated and treated properly, clinicians can reduce the frequency of ectopic eruption and subsequent impaction of the maxillary canine.

The simplest interceptive procedure that can be used to prevent impaction of permanent canines is the timely extraction of the primary canines. This procedure usually allows the permanent canines to become upright and erupt properly into the dental arch, provided sufficient space is available to accommodate them.

Various surgical and orthodontic techniques may be used to recover impacted maxillary canines.[28] The proper management of these teeth, however, requires that the appropriate surgical technique be used and that the clinician be able to apply measured forces in a favorable direction. This allows for complete control in efficient correction the impaction and for avoidance of damage to adjacent teeth. Careful selection of surgical and orthodontic techniques is essential for the successful alignment of impacted canines.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Power SM, Short MB. An investigation into the response of palatally displaced canines to the removal of deciduous canines and an assessment of factors contributing to a favourable eruption. Br J Orthod. 1993;20:215–23. doi: 10.1179/bjo.20.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.litsas G. A review of early displaced maxillary canines: Etiology, diagnosis and interceptive treatment. Open Dent J. 2011;5:39–47. doi: 10.2174/1874210601105010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishara SE. Impacted maxillary canines: A review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992;101:159–71. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(92)70008-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ericson S, Kurol J. Early treatment of palatally erupting maxillary canines by extraction of the primary canines. Eur J Orthod. 1988;10:283–95. doi: 10.1093/ejo/10.4.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell L, editor. An Introduction to Orthodontics. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 147–56. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacoby H. The etiology of maxillary canine impactions. Am J Orthod. 1983;84:125–32. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(83)90176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson G. A review of impacted permanent maxillary cuspids — diagnosis and prevention. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66:497–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker A, editor. The orthodontic treatment of impacted teeth. 2nd ed. Abingdon, Oxon, England: Informa Healthcare; 2007. pp. 1–228. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peck S, Peck L, Kataja M. The palatally displaced canine as a dental anomaly of genetic origin. Angle Orthod. 1994;64:249–56. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1994)064<0249:WNID>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baccetti T. A controlled study of associated dental anomalies. Angle Orthod. 1998;68:267–74. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1998)068<0267:ACSOAD>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM, editors. A textbook of oral pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1963. pp. 2–75. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ericson S, Kurol J. Longitudinal study and analysis of clinical supervision of maxillary canine eruption. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1986;14:112–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1986.tb01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ericson S. radiographic examination of ectopically erupting maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;91:483–92. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(87)90005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bedoya MM, Park JH. A review of the diagnosis and management of impacted maxillary canines. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:1485–93. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokich VG. Surgical and orthodontic management of impacted maxillary canines. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:278–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacoby H. The “ballista spring” system for impacted teeth. Am J Orthod. 1979;75:143–51. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(79)90183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crescini A, Giorgetti R, Cortellini P, Pini Prato GP. Tunnel traction of infraosseous impacted maxillary canines. A three-year periodontal follow-up. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994;105:61–72. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(94)70100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darendeliler AM. Treatment of an impacted canine with magnets. J Clin Orthod. 1994;28:639–43. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li LCF. Orthodontic traction of impacted canine using magnet: A case report. Cases J. 2008;1:382. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindauer SJ, Isaacson RJ. One-couple orthodontic appliance systems. Semin Orthod. 1995;1:12–24. doi: 10.1016/s1073-8746(95)80084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samuels RH. Two-archwire technique for alignment of impacted teeth. J Clin Orthod. 1997;31:183–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross Ll. nickel titanium closed-coil spring for extrusion of impacted canines. J Clin Orthod. 1999;33:74–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinha PK. Management of impacted maxillary canines using mandibular Anchorage. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;115:332–6. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalra V. the k-9 spring for alignment of impacted canines. J Clin Orthod. 2000;34:606–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hauser C. eruption of impacted canines with an australian helical archwire. J Clin Orthod. 2000;34:538–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowman SJ. the monkey hook: An auxiliary for impacted, rotated, and displaced teeth. J Clin Orthod. 2002;36:375–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park HS, Kwon OW, Sung JH. Micro-implant anchorage for forced eruption of impacted canines. J Clin Orthod. 2004;38:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel S. Alignment of impacted canines with cantilevers and box loops. J Clin Orthod. 1999;33:82–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]