Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections in patients with oral lichen planus (OLP) and to compare it with that of general population.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 60 patients were included in the study. Patients were selected from the outpatient department of Rama Dental College Research Centre, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh. Thirty patients with OLP were included in Group 1. Thirty age- and sex-matched healthy patients with no history of oral or skin lesions were included in Group 2. Detailed case history, biopsy (the most representative site of the lesion is chosen for specimen), detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and detection of anti-HCV antibody were carried out.

Results:

The serum of the entire study sample (Group 1 and Group 2) was tested for both hepatitis C antibodies and HBsAgs with the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test (using the third generation kit). It was found negative for both HBsAgs and hepatitis C antibodies.

Conclusion:

In the present study, all the samples including OLP patients and healthy patients were seronegative for both hepatitis B (HBsAg) and hepatitis C (HCV antibody).

KEY WORDS: Anti-HCV Abs, hepatitis B surface antigen, oral lichen planus, serum

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic common mucocutaneous inflammatory disorder of uncertain etiology[1] with characteristic clinical and pathological features affecting the skin, mucus membrane, nails, and hair.[2] The prevalence of LP seen in the general population varies according to different studies, but it is estimated to be 0.9–1.2%.[3]

LP is primarily a disease of middle-aged people[3] (with mean age of onset in 4th and 5th decades[4]) and is rare in children.[5] Women are affected more often than men.[3]

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is recognized as a chronic disease of cell-mediated immune damage to the basal keratinocytes in the oral mucosa that are recognized as being antigenetically foreign or altered.[6]

Virtually, all lesions result from interplay of host, lifestyle, and environmental factors and OLP is no exception. Cell-mediated immunity appears to play a major role in the pathogenesis of OLP, possibly initiated by endogenous and exogenous factors in persons with genetic predisposition to the development of the lesion.[7]

OLP has been reported to be associated with a variety of totally unrelated disorders,[8] like malignancies, gastrointestinal diseases, ulcerative colitis, diabetes mellitus, myasthenia gravis, lupus erythematosis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and chronic active hepatitis.[8,9]

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a type of hepadnavirus.[10] An association between LP and HBV infection has been suggested as hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive patients may have double the risk of developing LP compared with HBsAg-negative patients. In addition, there are reports of anti-HBV antibodies in LP patients of lichenoid eruption following administration of different HBV vaccines.[11]

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the major causes of chronic hepatic disease worldwide.[12] It has been estimated that HCV-infected patients have at least twice the risk of developing LP than the general population. The reports associating LP with HCV reveal marked geographic variation.[1] The association seems to be strong in Japanese and Mediterranean population, probably due to the higher prevalence of HCV infections.[13]

Hepatitis is the commonly encountered viral infection in India. HBV infection is prevalent compared to HCV infection.[14] The detection of HBV and HCV infections in the patients having OLP may throw light on the mysterious association between these viruses and the pathogenesis of OLP.

This study aims to detect HBsAg and antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV Abs) in patients with OLP to correlate its role in the pathogenesis of OLP.

Materials and Methods

A total of 60 subjects were included in the study. Subjects were recruited from the outpatients attending Rama Dental College and Research Centre, Kanpur.

Subjects were subgrouped into two groups:

Group 1: Study group

Thirty patients with OLP were included in this group. The patients were diagnosed on the basis of typical clinical and histological features.

Group 2: Control group

Thirty age- and sex-matched healthy subjects with no history of oral or skin lesions were included in this group.

Detailed case history (clinical and personal history followed by through intraoral examination), biopsy (the most representative site of the lesion is chosen for specimen), and written consent of the patients were obtained as per the proforma attached [Annexures 1 and 2] based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

For Group 1

Randomly selected patients with OLP, diagnosed on the basis of typical clinical and histological features.

Clinical criteria

Reticular/annular/papular/erosive type [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Reticular oral lichen planus lesion seen on buccal mucosa and palate

Histopathologic criteria

Band of inflammatory cells (lymphocytes). Liquefaction degeneration and eosinophilic coagulum.

For Group 2

Randomly selected males and females.

Subjects age and sex matched with those of Group 1

Exclusion criteria

For Group 1

Patients having drug-induced lichenoid reaction.

Patients who are on antiviral therapy for any other systemic conditions.

Patients having systemic hypertension.

Patients below 18 years of age.

For Group 2

Patients having systemic hypertension.

Patients below 18 years of age.

Patients who are on antiviral therapy for any other systemic conditions.

Procedure

Following aseptic procedures, 5 ml of intravenous blood of the patient was drawn using 22-gauge sterile needle and syringe from median forearm vein. The blood was allowed to clot in a test tube and serum was separated by centrifugation for 10min at 5000 rpm. Serum was separated and transferred into a sterile sample storage vial and was stored in deep freezer at -20°C till further tests were carried out.

The serum was subjected to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using third generation ELISA kit, SURFACE B-96 (TMB) and SP-NANBASE C 96 3.0, respectively, using automated ELISA system.

Detection of HBsAg

The test procedure was followed as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Test procedure

All the kit reagents and samples were brought to room temperature for 30 min and mixed carefully before the assay.

Required number of plates (wells) were taken and fixed to the frame.

One well was reserved for blank. 50 μl of negative control was pipetted into each of the three wells, 50 μl of positive control into each of the two wells, and 50 μl of each specimen into the remaining wells.

50 μl of anti-HBs peroxidase solution was pipetted into each well except the blank.

Plate was gently tapped.

Protective backing was removed from the adhesive slip and pressed onto the reaction plate to seal it tightly.

The reaction plate was incubated at 37°C for 80 minutes.

-

At the end of the incubation period, the adhesive slip was removed and the plate was washed using washing procedure.

Washing procedure

- Preparation of the washing solution: Dilute washing solution D (20×) concentrate with distilled water to obtain a 1: 20 dilution.

- Plate washing: 6 cycles with at least 0.5 ml washing buffer per well per cycle.

- Plate was blot dried by inverting the plate and tapping firmly onto absorbent paper.

50 μl of TMB substrate solution A was first added and then 50 μl of TMB substrate solution B was added into each well including the blank and mixed carefully.

The plate was covered with black cover and incubated at room temperature for 30 min.

The reaction was stopped by adding 100 ml of 2N Sulfuric acid to each well including blank.

The absorbance values of positive control, negative control, and specimen were read at 450 nm against air within 30 min.

Principle of the test

SURFACE B-96 (TMB) is a solid-phase enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) based on the sandwich principle.

The solid phase of the microtiter plate is made of polystyrene wells coated with mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for HBsAg, whereas guinea pig polyclonal antibody purified by affinity chromatography is used to prepare the anti-HBs-peroxidase (horseradish conjugate in the liquid phase).

When a serum or plasma specimen containing HBsAg is added to the anti-HBs antibody-coated wells together with the peroxidase conjugated anti-HBs antibody and incubated, an antibody–HBsAg–antibody-peroxidase complex will form on the wells.

After washing the microtiter plate to remove unbound material, a solution of TMB substrate was added to the wells and incubated. A color develops in proportion to the amount of HBsAg bound to anti-HBs. The peroxidase–TMB reaction was stopped by addition of sulfuric acid. The optical density of developed color was read with a suitable photometer at 450 nm with a selected reference wavelength at 620–690 nm.

Calculation of cutoff value

Calculation of negative control mean (NCx)

![]()

Cutoff value: NCx + 0.025

Interpretation

Specimens with absorbance values less than the cutoff value were non-reactive and were considered negative for HBsAg.

Specimens with absorbance values greater than or equal to the cutoff value were considered initially reactive. The original specimens were retested in duplicate.

If both absorbance values in the retest were less than the cutoff value, the specimens were considered negative for HBsAg.

If in the retest at least one of the two absorbance values was greater than or equal to the cutoff value, then the specimens were considered as repeated HBsAg positive.

Detection of anti-HCV antibody

Test procedure

All the kit reagents and samples were brought to room temperature for 30min and mixed carefully before the assay.

-

The diluted conjugate was prepared

- Only clean containers were used to avoid contamination.

- Diluted conjugate was prepared by making 1:21 dilution of conc. anti-h-1 gG-HRPO conjugate with conjugate diluent.

- Excess diluted conjugate solution was discarded after use.

One well was reserved for blank

The required number of wells was prepared, including one well for blank, two wells for negative control, three wells for positive control, and one well for each specimen.

-

Sample input:

- 200 μl specimen diluent was added to each appropriate well assigned for specimens and controls in HCV antigens plate.

- 10 μl of positive control, negative control, and specimen was added to each appropriate well.

- It was mixed well by tapping the plate gently.

Plate was sealed with an adhesive slip.

Plate was incubated at 37 ± 1°C for 60 min.

At the end of the incubation period, the adhesive slip was removed carefully and discarded.

-

The plate was washed using washing procedure.

Washing procedure

- Preparation of the washing solution: Dilute washing solution D (20×) concentrate with distilled water to obtain a 1: 20 dilution.

- Plate washing: 6 cycles with at least 0.5 ml washing buffer per well per cycle.

- Plate was blot dried by inverting the plate and tapping firmly onto absorbent paper.

100 μl of the diluted conjugate was added to each well, except the blank.

Plate was sealed with an adhesive slip.

Plate was incubated at 37 ± 1°C for 30 min.

At the end of the incubation period, the adhesive slip was removed carefully and discarded.

The plate was washed using washing procedure.

50 μl of TMB substrate solution A was first added and then 50 μl of TMB substrate solution B was added into each well including the blank and mixed carefully.

The plate was covered with black cover and incubated at room temperature for 30 min.

The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl of 2N sulfuric acid to each well including blank.

The absorbance values of positive control, negative control, and specimen were read at 450 nm against air within 15 min.

Principle of the test

SP-NANBASE C-96 3.0 adopts the second antibody–sandwich principle as the basis for the assay to detect antibody to HCV (anti-HCV). It is an enzyme immunoassay kit which uses recombinant HCV antigens (core, NS3, NS4, and NS5 antigens) for the detection of anti-HCV in human serum or plasma. These antigens constitute the solid phase.

When human serum or plasma is added to the well, the HCV antigens and anti-HCV will form complexes on the wells if anti-HCV is present in the specimen.

The wells were washed to remove the unbound material. The diluted anti-human-IgG-HRPO conjugate was added to the wells and resulted in the formation of HCV, anti-HCV and anti -human IgG HRPO complex.

After washing out the unbound conjugate, TMB substrate solution was added for color development. The intensity of color development was proportional to the amount of antibodies present in the specimen. The optical density of developed color was read with a suitable photometer at 450 nm with a selected reference wavelength at 620–690 nm.

Calculation of the tested data

Calculation of negative control mean

![]()

Negative control mean (NCx) = sum of above/2

Calculation of positive control mean

Positive control mean (PCx) = sum of above/3 Cutoff value was NCx + (PCx)/4

Results interpretation

Specimens with cutoff index <1.0 were considered non-reactive by the criteria of SP-NANBASE C-96, 3.0.

Specimens with cutoff index >1.0 were considered as initially reactive and were retested in duplicate. If both cutoff indexes of the duplicate were greater than 1.5, the specimen was considered to be repeatedly reactive for anti-HCV by the criteria of SP-NANBASE C-96, 3.0.

Initially reactive specimens, of which both cutoff indexes of the duplicate retest were less than 1.0, were considered non-reactive for anti-HCV.

If one of the two cutoff indexes of the duplicate was greater than 1.0 but less than 1.5, the specimen was interpreted as questionable and this individual was monitored in the follow-up samples.

If one of the cutoff indexes of the duplicate was greater than 1.5 and the other one was less than 1.0, it indicated unusual experimental error. The test was repeated again.

Statistical analysis

Since all the samples in our study (study group and control group) were negative for both hepatitis C (HCV antibodies) and hepatitis B (HBsAg) virus infections, no statistical comparisons could be applied.

Results

The present study was conducted among the subjects attending the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology. The study population was divided into two groups: Group 1 consisted of 30 OLP patients and Group 2 consisted of 30 healthy subjects.

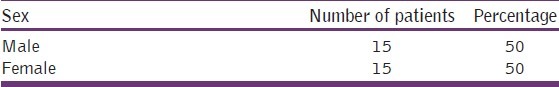

Among the 30 OLP patients, 15 (50%) were males and 15 (50%) were females [Graph 1, Table 1].

Graph 1.

Distribution of study subjects according to gender among the cases

Table 1.

Distribution of study subjects according to gender among the cases

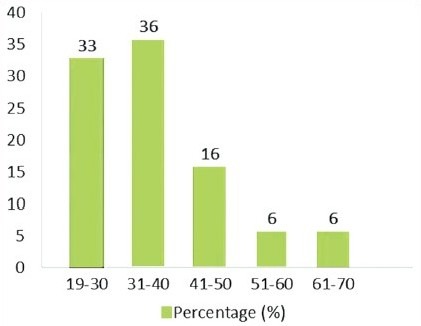

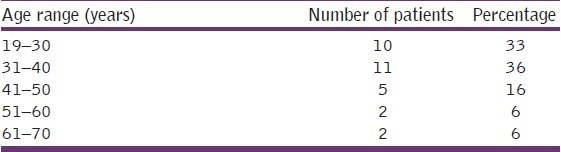

A maximum numbers of patients (36%) were in the age range of 31–40 years, followed by 33% of the study population in 19–30 years range, 16% in 41–50 years, 6% in 51–60 years, and 6% of the study subjects were in 61–70 years age group [Graph 2, Table 2].

Graph 2.

Distribution of the study subjects according to age among the cases

Table 2.

Distribution of the study subjects according to age among the cases

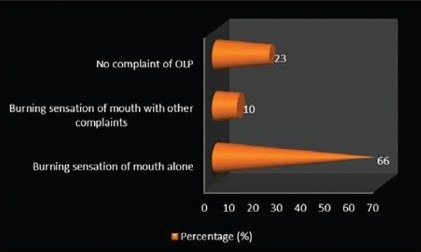

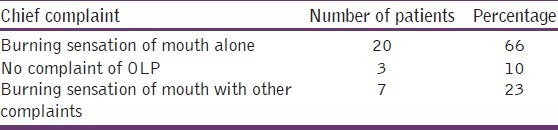

The study participants had come with various chief complaints to the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology. The most common complaint was burning sensation of buccal mucosa or gingival (66%). Few patients (23%) complained of burning sensation, with other complaints like white patch, white lines, and roughness of the mucosa. Rest of them (10%) had no complaint of OLP (these patients had come to the hospital for other complaints like decayed tooth; they were diagnosed by the dentist during routine oral cavity examination) [Graph 3, Table 3].

Graph 3.

Distribution of study subjects according to chief complaint

Table 3.

Distribution of study subjects according to chief complaints among the cases

Personal history of the study patients revealed that 4 (13%) of them were diabetic and another 4 (13%) of them gave the history of excessive stress [Graph 4, Table 4].

Graph 4.

Distribution of study subjects according to personal history and medical history among the cases

Table 4.

Distribution of study subjects according to personal history and medical history among the cases

Most of the OLP patients (75%) in the current study did not have any habit of tobacco or betel nut usage. However, 5 (16%) of them gave the history of smoking, 2 (6%) of them had tobacco chewing habit, and 1 (3%) had betel nut chewing habit [Graph 5, Table 5].

Graph 5.

Distribution of study subjects according to harmful habits among the cases

Table 5.

Distribution of study subjects according to harmful habits among the cases

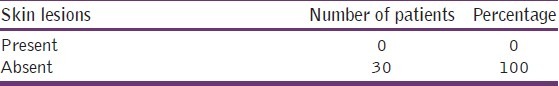

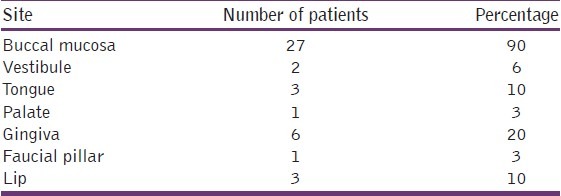

Skin lesions were not found in any of the 30 OLP patients in our study [Table 6].

Table 6.

Distribution of study subjects according to skin lesions among the cases

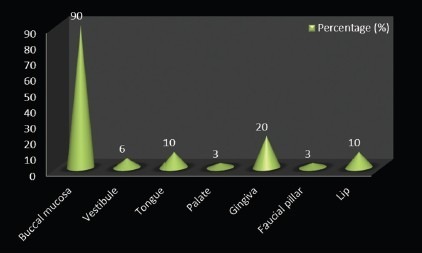

Clinically, OLP can express itself in multiple regions in one person. In the present study, lesions occurring in different sites were considered separately. Graph 6 and Table 7 show the distribution of study subjects according to the site of OLP lesion. A majority (90%) of them had OLP in buccal mucosa, 6% had it in vestibule, 10% over the tongue, 3% of the lesions were on palate, 20% in gingival, another 3% on faucial pillar, and 10% of the cases had OLP lesions on the lip.

Graph 6.

Distribution of study subjects according to site-specific distribution of OLP among the cases

Table 7.

Distribution of study subjects according to site-specific distribution of OLP among the cases

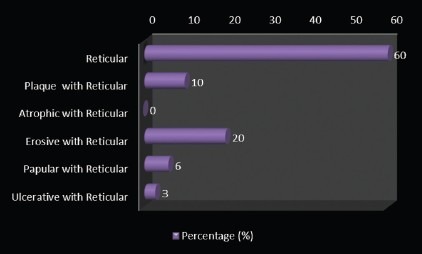

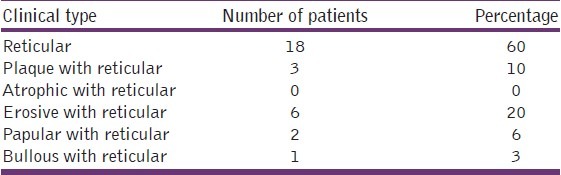

Clinically few patients had a combination of different types of OLP, but the maximum number of patients (60%) had only reticular type. Three (10%) of them had plaque with reticular type, 6 (20%) had erosive with reticular type, 2 (6%) had papular with reticular type, and 1 (3%) of them had bullous with reticular type of OLP [Graph 7, Table 8].

Graph 7.

Distribution of study subjects according to the clinical type of the lesion among the cases

Table 8.

Distribution of study subjects according to the clinical type of the lesion among the cases

The sample in Group 2 (control group) consisted of equal number of subjects, whose age and sex were matched with those of Group 1.

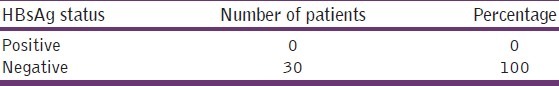

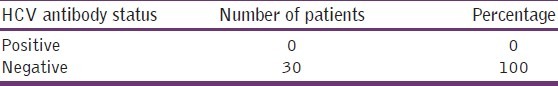

The serum of the entire study sample (Group 1 and Group 2) was tested for both hepatitis C antibodies and HBsAgs with the ELISA test (using the third generation kit). It was found negative for both HBsAgs [Table 9] and hepatitis C antibodies [Table 10].

Table 9.

Distribution of study subjects according to HBsAg status among the cases

Table 10.

Distribution of study subjects according to HCV antibody status among the cases

Discussion

LP is a mucocutaneous disease characterized by a cellular inflammatory infiltrate enriched in CD4+ cells, by the presence of acidophilic bodies that may represent apoptotic epithelial cells, and by vacuolating degeneration of the basal epithelial layer.[15] HCV infection is a health problem worldwide. Acute hepatitis C occurs in a minority of the infected patients, 6–12 weeks after acquisition of the virus. Several extrahepatic diseases have been reported to be associated with HCV infection.[15] Among these extrahepatic manifestations, LP is well known to be associated with chronic liver diseases, although its association with HCV infection is still a debated issue, appearing to be proven only in some geographic areas, such as Japan and Southern Europe.[15]

Compared with skin lesions, mucosal affections are far more chronic in nature and often persist for many years. Because of the morbidity associated with these oral lesions and their propensity for malignant development, oral LP occupies an important place in the practice of oral pathology and medicine.[16]

The available reports indicate that the prevalence of HCV antibodies in patients with mucosal and cutaneous LP is significantly higher than that of the control populations in Germany, Italy, Spain, the USA, and Japan, suggesting an etiologic role for HCV in LP. However, studies in France and England could not demonstrate a statistically significant association between HCV and LP.

Hence, this study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of hepatitis C and hepatitis B in patients with OLP and to correlate its possible role in pathogenesis of OLP.

Thirty patients with OLP and 30 age- and sex-matched healthy individuals were included in the study. OLP was diagnosed by clinical examination and confirmed histologically.

Of the 30 patients included in the study, 15 were males and 15 were females. This finding was not in agreement with the previous reports which suggest female predominance.[3,12] Most of the patients were from the age group 31–40 years, with an average of 33.5 years, which is in accordance with the literature.[3,17] This age group is the one which is more prone to stressful conditions. This was supported by our clinical data where the patients admitted that they were under stressful conditions (13%).

Thirteen percent of the cases were diabetic in our study. Contrasting reports have been stated in the literature regarding association of diabetes mellitus and LP, with some stating an association to be present while others opposing it.

Among the 30 OLP patients, 16% had the habit of smoking cigarette, 6% had the habit of chewing tobacco, and 3% had the habit of chewing betel nut. Prevalence of OLP has been reported to be higher (3.7%) in those with habits and lower (0.3%) in non-users of tobacco.[7]

Many patients in our study had multiple site involvement. Buccal mucosa was the commonest site affected (90%). The next common site was gingiva (20%), followed by tongue (10%), vestibule (6%), palate (3%), and faucial pillar (3%). This finding in our study is in accordance with a previous study which stated that the posterior part of the buccal mucosa is the most common site for OLP.[18,19]

From all 60 patients included in the study, 5 ml of intravenous blood was collected under aseptic precautions, centrifuged, and the serum was separated. Serum was subjected to analysis for the presence of HBV and HCV by detection of HBsAg and HCV antibodies.

HBsAg and HCV antibodies were detected by third generation ELISA kits called SURFACE B-96 (TMB) and SP-NANBASE C-96 3.0, respectively, using automated ELISA system. The results were interpreted as positive and negative according to the manufacturer's instructions.

There may be underlying differences among the populations in which the various studies were conducted that may help explain why a difference in the association between HCV and OLP was seen. These may include the prevalence of HCV infection, the prevalence of other etiologic factors of OLP, differences in genetic susceptibility to HCV-induced OLP, and differences in the genotypes of HCV.[20]

In a study conducted at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India, among 94,716 blood donations, the overall number of HCV-seropositive donations was 537, with the prevalence rate of 0.57%.[21] The prevalence of hepatitis C in Indian population shows regional variation (Arunachal Pradesh 7.89%, Andhra Pradesh 1.4–2.02%, Maharashtra 0.09%, West Bengal 0.71%).[22] The overall prevalence of HCV in India is low compared to those countries which show correlation between these infections and OLP.

It might be argued that the true association between LP and HCV is due to heterogeneity. The peculiar differences in heterogeneity in geographic regions seen in the association of LP and HCV are difficult to explain and have been hypothesized to be the result of differences in genetic factors, such as different human leukocyte antigen types.[23]

According to some authors, OLP lesions in patients with HCV cannot determine a link between OLP and hepatitis C. However, the presence of HCV RNA in epithelial cells in oral tissues from OLP lesions may suggest HCV action. It is believed that HCV acts locally, altering the function of the epithelial cells, or that the immune response of the host to HCV is responsible for the development of OLP. Thus, host factors rather than geographic factors may be more important in the pathogenesis of HCV-related OLP.[24]

Virology studies have shown no differences in the serum of HCV RNA levels or in the HCV genotypes between HCV-infected patients with LP and those without LP. It would seem likely, therefore, that host rather than viral factors must play an important role in the pathogenesis of HCV-related LP.[22]

Some authors have investigated the relationship between LP and genotypes of HCV; however, there have been no cases in which the identification of a specific genotype/subtype of HCV has been associated with patients with LP. These results suggest that the pathogenesis of OLP is due to factors related to the host rather than the virus itself.[25]

The entire sample of 30 OLP patients in our study was seronegative for HBsAg, suggesting that there was no correlation between HBV infection and OLP. However, even the control group (30 healthy subjects) was negative for HBsAg, suggesting that probably an even larger sample size is required for accurate evaluation.

Though there are only few reports in the literature correlating HBV infection associated with LP (many of these published studies were conducted in Western countries where prevalence of hepatitis C is more than hepatitis B infection), we included this in our study as hepatitis B infection is more prevalent in India. (In a study conducted at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India, among 94,716 blood donations, the overall number of HBV-seropositive donations was 1353, with the prevalence rate of 1.43%.[21])

Reasons that can be considered to explain why HBV infection may cause LP include: LP could be a cytotoxic reaction to keratinocytes expressing HBs and not epitopes shared by the hepatocytes damaged by the virus as suggested.[26] In the case of HBV vaccine, it has been suggested that cell-mediated autoimmune destruction of keratinocytes is triggered by the viral antigens present in the vaccine.[27]

Conclusions

Since the first report of association of LP and HCV was published in the year 1991, many more studies have been carried out to confirm or rule out the association between the two. The results have been even more confusing since in some geographic areas it has come positive and in some others it has come negative. This association is well proven in countries like Japan (62%) and Mediterranean countries, whereas it has been found as not at all associated in countries like England (0%). One study published in the year 2002 (Indian J Dermatovenerolleprol 2002;68:273-74) conducted among 65 LP cases in Calcutta revealed no association between LP and HCV infection. Given the morbidity and health care costs associated with LP, it is important to establish whether HCV has a strong association with LP.

Hence, we conducted this study to determine the prevalence and association between the hepatitis B and C virus infections and OLP. Our study had a total sample size of 60 subjects (30 OLP patients and 30 healthy subjects). The test was performed on the serum sample using third generation ELISA kits for both hepatitis B (HBsAg) and hepatitis C (HCV antibodies).

In the present study, all the samples including OLP patients and healthy subjects were seronegative for both hepatitis B (HBsAg) and hepatitis C (HCV antibodies).

There are many reasons (as already stated) for this variation based on the geographic area, which include the prevalence of HBV and HCV infections, the prevalence of other etiologic factors of OLP, differences in genetic susceptibility to HCV-induced OLP, differences in the genotypes of HCV, and cytotoxic reaction to keratinocytes expressing HBsAg.

Though in our study, the association between OLP and hepatitis B and/or hepatitis C virus could not be proved, it had a few limitations. The major limitation of our study was small sample size which may not be representative of the whole of the population. Hence, a study with larger sample size is required to denote if there exists any association between OLP and hepatitis B and/or hepatitis C virus.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Femiano F, Scully C. Functions of the cytokines in relation oral lichen planus-hepatitis C. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10:E40–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghodsi SZ, Daneshpazhooh M, Shahi M, Nikfarjam A. Lichen planus and Hepatitis C: A case-control study. BMC Dermatology. 2004;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lozanda-Nur F, Miranda C. Oral Lichen Planus: Epidemiology, Clinical, Characteristics, and Associated Diseases. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 1997;16:273–7. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(97)80016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, Griffiths M, Sugerman PB, Thingprasom K, et al. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: Report of an international consensus meeting. Part 1. Viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scully C, Almeida O, Welbury R. Oral lichen planus in childhood. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:131–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb06905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ismail SB, Kumar SKS, Zain RB. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid reaction: Etiopathogesis, dagnosis, management and malignant transformation. J Oral Sci. 2007;49:89–106. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.49.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scully C, Beyli M, Ferreiro MC, Ficarra G, Gill Y, Griffiths M, et al. Update on oral lichen planus -etiopathogenesis and management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:86. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J AM Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593–619. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70241-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero MA, Seoane J, Varela-Centelles P, Diz-Dios P, Otero XL. Clinical and pathological characteristics of oral lichen planus in hepatitis C positive and negative patients. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2002;27:22–6. doi: 10.1046/j.0307-7772.2001.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ananthanaryana R, Jayaram Paniker CK. Textbook of Microbiology. 5th ed. Chennai: Orient Longman Publication; 1978. pp. 508–19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lodi G, Porter SR. Hepatitis C virus infection and lichen planus: A short review. Oral Dis. 1997;3:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1997.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mollaoglu N. Oral lichen planus: A review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Sur. 2000;38:370–7. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2000.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Robaee AA, Al Zolibani AA. Oral lichen planus and hepatitis C virus: Is there real association? Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2006;15:14–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saravanan S, Velu V, Kumarasamy N, Shankar EM, Nandakumara S, Murugavel KG, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection among patients with chronic liver disease in South India. Int JInfect Dis. 2008;12:513–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilli M, Penna A, Zerbini A, Vescovi P, Manfredi M, Negro F, et al. Oral lichen Planus Pathogenesis: A Role for the HCV-Specific Cellular Immune Response. Hepatology. 2002;36:1446–52. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.37199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh LJ, Savage NW, Ishii T, Seymour GJ. Immunopathogenesis of oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1990;19:389–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1990.tb00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scully C, El-Kom M. Lichen planus: review and update on pathogenesis. J Oral Pathol. 1985;14:431–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1985.tb00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisen D, Carrozzo M, Bagan Sebastian JV, Thongprasom K. Oral lichen planus: clinical features and management. Oral Dis. 2005;11:338–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisen D. The therapy of oral lichen planus. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4:141–58. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chainani-Wu N. Hepatitis C virus and lichen planus: A review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:171–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrozzo M, Gandolfo S, Lodi G, Carborne M, Garzino-Demo P, Carbonero C, et al. Oral lichen planus in patients infected or not infected with hepatitis C virus: The role of autoimmunity. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28:16–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shengyuan L, Songpo Y, Wen W, Wenjing T, Haitao Z, Binyou W. Hepatitis C Virus and Lichen Planus - A Reciprocal Association Determined by a Meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1040–7. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Mattos Camargo Grossmann S, de Aguiar MC, Teixeira R, Vieira do Carmo MA. Oral Lichen Planus and Chronic Hepatitis C A Controversial Association. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127:800–4. doi: 10.1309/HDWCT36P0GMGP40V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meena M, Jindal T, Hazarika A. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among blood donors at a tertiary care hospital in India: A five-year study. Transfusion. 2010 Jul 20; doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02801.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunha KS, Manso AC, Cardoso AS, Paixao JB, Coelho HS, Torres SR. Prevalence of oral lichen planus in Brazilian patients with HCV infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005 Sep;100:330–3. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rebora A, Rongioletti F. Lichen planus as a Side Effect of HBV Vaccination. Dermatology. 1999;198:1–2. doi: 10.1159/000018054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Limas C, Limas CJ. Lichen Planus in Children: A Possible Complication of Hepatitis B Vaccines. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:204–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]