Abstract

Crohn′s disease is a granulomatous inflammatory bowel disease and was described in 1932 as a chronic granulomatous disorder of the terminal ileum and is now considered a distinct member of the inflammatory bowel disease family. It may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract. Oral Crohn′s disease has been reported frequently in the last three decades with or without intestinal manifestations. In the latter case, it is considered as one of the orofacial granulomatosis. There has been much doubt whether intestinal manifestations of Crohn′s disease will eventually develop in the orofacial granulomatosis. We present a female patient aged 22 years with prominent clinical findings such as persistent swelling of lower and upper lip with fissuring and angular cheilitis, granulomatous gingival enlargement, and cobblestone or corrugated appearance of labial mucosa, which are suggestive of Crohn′s disease, but with no evidence of other gastrointestinal involvement. The patient underwent surgical treatment with external gingivectomy procedure. A 6-month follow-up showed minimal recurrence.

KEY WORDS: Crohn′s disease, orofacial granulomatosis, gingival enlargement

Crohn′s disease is a chronic granulomatous inflammatory bowel disease characterized by localized areas of non-specific, non-caseating granulomas. Among the chronic forms of inflammatory bowel diseases, it can be differentiated on the basis of histology, clinical presentation, laboratory investigations, and disease progression. Although considerable data are available regarding the systemic features of Crohn′s disease, data concerning the oral and dental findings are limited and show that 9% of patients with Crohn′s disease have oral manifestations.[1] The oral findings associated with Crohn′s disease were initially described in 1969, first by Dyes et al. detailing two chronic disease patients[2] and later by Issa in 1971.[1]

Oral Features of Crohn′s Disease [2–4]

Persistent, diffuse soft tissue swelling of lips and buccal mucosa, which is edematous or firm on palpation. Lip involvement can lead to vertical fissuring.

Cobblestone or corrugated appearance of buccal or labial mucosa.

Linear aphthous ulcerations.

Angular cheilitis.

Granular, edematous, hyperplastic enlargement of gingival, involving attached gingiva and extending up to mucogingival line with or without ulcerations.

Persistent lymphadenopathy of submandibular lymph nodes which are firm, occasionally tender to painful.

Epithelial tags or folds (fibroepithelial hyperplasia) seen on buccal mucosa, vestibule, or retromolar areas.

Extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn′s disease have been recognized, mainly pyoderma gangrenosum or erythema nodosum. Skin lesions seem to be especially common. Verbov in 1973 reported 106 cases of Crohn′s disease, 85% of which had skin manifestations.[1]

We hereby report a case of oral Crohn′s disease without intestinal manifestations and with typical intraoral findings which are useful in evaluating future cases.

Case Report

A 22-year-old female of Indian origin was referred to the Department of Periodontics, with a complaint of persistent swelling of the lower lip with recurrent episodes. Extraoral findings revealed mild angular cheilitis and the lower lip was greatly swollen with marked vertical fissuring [Figure 1]. Intraoral findings revealed generalized granulomatous gingival hyperplasia, extending up to the mucogingival line and which was markedly seen on facial aspect covering almost the entire length of clinical crowns [Figures 2–4]. On palpation, gingiva was tender. There was marked cobblestone appearance of labial mucosa on the right side of lower lip which was tender on palpation. The right and left submandibular lymph nodes were palpable and tender. Family and medical history were not significant. Patient did not give any history of gastrointestinal disturbances.

Figure 1.

Marked vertical fissuring seen in the lower lip

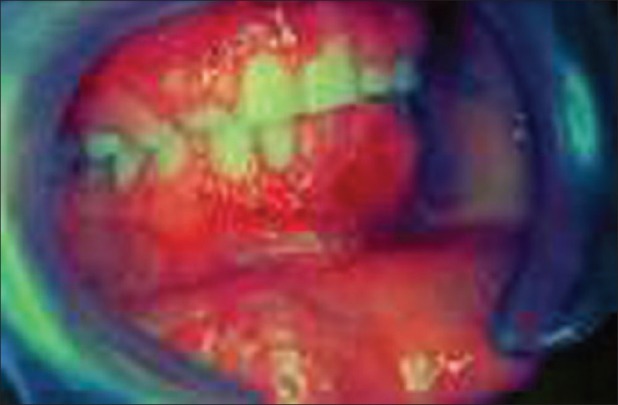

Figure 2.

Gingival hyperplasia in the right lateral incisor-canine region

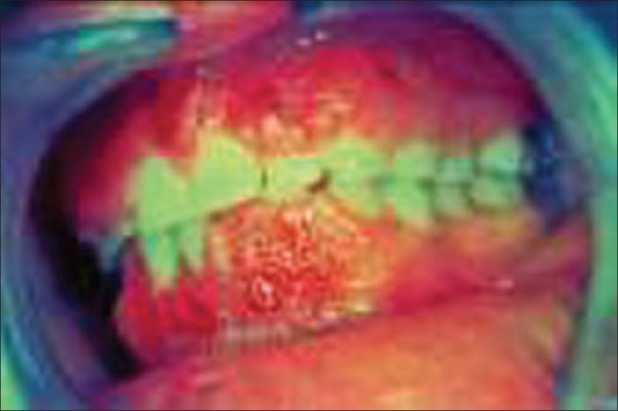

Figure 4.

Marked erythema seen in the affected gingiva

Figure 3.

Gingival hyperplasia in the left anterior region

Laboratory investigations

Hematological examination was performed and results were within normal limits. However, the peripheral blood smear showed evidence of microcytic hypochromic anemia. Further blood investigations showed low serum iron and folate levels and raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Mantoux test and Kveim test proved negative, which ruled out active tubercular infection and sarcoidosis. Biopsy was also performed to rule out intestinal involvement.

Intraoral radiological examination revealed normal radiological features with mild loss of interdental bone in relation to the mandibular posterior teeth, which is common in this age group.

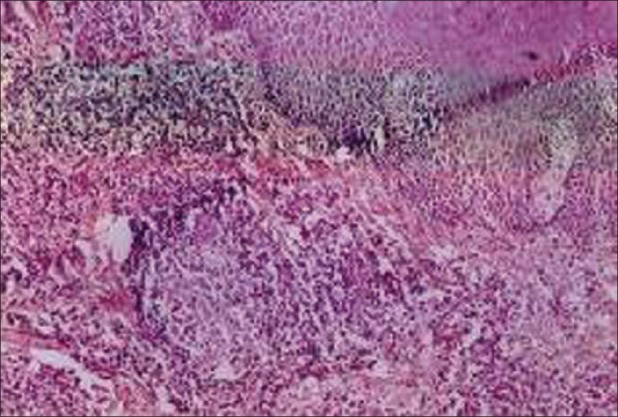

Histopathologic examination

On histopathologic examination [Figure 5], the lesion was seen to be covered by stratified squamous parakeratinized epithelium, which varied from atrophic to hyperplastic in areas. Areas of spongiosis and ulceration were also evident. Connective tissue was fibrocellular and edematous, moderately infiltrated by chronic inflammatory cells, chiefly lymphocytes and macrophages. Blood vessels, areas of hemorrhage, and isolated multiple non-caseating granulomas specifically located subepithelially were also seen.

Figure 5.

Non caseating granuloma seen in the connective tissue

Each non-caseating granuloma was loosely textured and consisted of a central mass of epithelioid cells surrounded by chronic inflammatory cells and occasional foreign body type or Langhan′s type of giant cells.

Diagnosis

Based on our clinical findings, histopathologic examination, and results of laboratory investigations, we arrived at a diagnosis of oral Crohn′s disease without intestinal manifestations.

Treatment

After performing possible investigations, our treatment depended mainly on anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroid supplements. Topical steroid applications were advised for painful oral ulcerations. The angular cheilitis and oral ulcerations responded to the use of 1% hydrocortisone ointment and vitamin supplements. External gingivectomy was planned quadrant-wise after thorough oral prophylaxis and sub gingival scaling.

The patient was followed up for approximately 15 months during which time no gastrointestinal symptoms were noticed. A repeat barium meal and follow-up were made. Repeated hematological tests showed no marked variation from the initial findings.

The clinical outcome and improvement in this patient was not satisfactory. Normal appearance of the gingiva was not achieved even though there was dramatic improvement with oral ulcerations and lip swelling [Figures 6 and 7].

Figure 6.

Post-operative extraoral appearance

Figure 7.

Intraoral post-operative appearance

Discussion

The underlying granulomatous inflammation of Crohn′s disease can involve any segment of the gastrointestinal tract. While the etiology is currently unknown, immunological dysfunction may play a major role in disease development. However, it is difficult to distinguish between oral Crohn′s disease and other types of orofacial granulomatoses.[5,6] At the present time, however, the diagnosis is essentially a clinical one and reinforced by histopathologic study of tissue removed at biopsy. Sigmoidoscopy alone does not eliminate the possibility of intestinal disease and a biopsy is essential because positive findings have been reported in cases with normal sigmoidoscope appearance.

Numerous investigators have proposed a prominent role of altered host immunity in the pathogenesis of Crohn′s disease. Reduced mucosal barrier factors and increased intestinal permeability was reported, yet follow-up studies have failed to confirm this finding. Examination of neutrophil functions has yielded conflicting results including reduced migration, chemotaxis, and superoxide anion production. Inhibitors to both chemotactic factors and leukocyte chemotaxis have been detected in the sera of patients with Crohn′s disease and ulcerative colitis.[7] More recently, circulating interleukin-6 (IL- 6) levels were found to be significantly elevated among Crohn′s disease patients, regardless of anti-inflammatory medication.[8]

Nutritional or dietary factors such as a negative history of breast feeding, increased sugar intake, and increased ingestion of food additives or chemicals reportedly can contribute to an increased incidence of Crohn′s disease.[9]

Microscopically, the initial lesion starts as a focal inflammatory infiltrate around the intestinal crypts, followed by ulceration of superficial mucosa. Later, inflammatory cells invade the deep mucosal layers and, in that process, begin to organize into non-caseating granulomas. The granulomas extend through all the layers of the intestinal wall and into the mesentery and the regional lymph nodes. Neutrophil infiltration into the crypts forms crypt abscesses, leading to destruction of the crypt and atrophy of the colon. Chronic damage may be seen in the form of villous blunting in the small intestine as well. Ulcerations are common and are often seen in a background of normal mucosa. Although granuloma formation is pathognomonic of Crohn′s disease, its absence does not exclude the diagnosis.[10] Tooth pastes containing silica and silicates that are capable of inducing granuloma formation can increase the incidence of Crohn′s disease. To date, however, scientific evidence concerning this hypothesis is limited and inconclusive.[11]

In the absence of intestinal manifestations, the diagnosis of oral Crohn′s disease usually depends on clinical appearance together with histological findings of non-caseating epithelioid granulomas. Histologically, however, it is difficult to distinguish between oral Crohn′s disease and other types of granulomatoses. The latter is a generalized term used to describe a group of chronic disorders of unknown etiology characterized by facial and lip swellings, gingival enlargements, oral ulcerations, and a history of facial nerve paralysis in some cases.

The association of severe progressive periodontal destruction with Crohn′s disease was reported by Lamster et al. in 1978. Yet, in 1982, Lamster et al. detected “overt oral disease” in only 2 of 10 inflammatory bowel disease patients with no direct reference to periodontal disease status. But in our patient, there was no detectable periodontal involvement. In 1988, Vandyke et al. reported 20 inflammatory bowel disease patients, of whom only 9 patients showed periodontal diseases and altered neutrophil function.[12]

Controversy continues about whether intestinal Crohn′s disease will eventually develop in some of these patients with only oral manifestations and, if so, in how many patients and after how long. The answer to these questions is not clearly resolved.

In our patient, intra- and extraoral manifestations, along with histopathologic findings, were similar to those of Crohn′s disease, without intestinal manifestations. Ghandour et al. stated that the intestinal manifestations can appear as late as 9 years after the oral lesions.[1] A 15-month follow-up period of our patient showed minimal recurrence of the gingival lesions. Extraoral healing was satisfactory. However, long-term follow-up of these patients would be wise. In the case of abdominal symptoms, investigations should be repeated.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Ghandour K, Issa M. Oral Crohn′s disease with late intestinal manifestations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:565–7. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90495-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalmar JR. Crohn′s disease: Orofacial considerations and disease pathogenesis. Periodontology 2000. 1994;6:101–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyldesley WR. Oral Crohn′s disease and related conditions. Br J Oral Surg. 1979;17:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0007-117x(79)90001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Field EA, Tyldesley WR. Oral Crohn′s disease revisited-a 10-year-review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;27:114–23. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(89)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM, editors. 4th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1983. A text book of oral pathology; pp. 342–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peter C, Reade , Bryan G, Radden . Oral Diseases in the Tropics. Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1993. Non-microbial inflammatory oral mucosal lesions; p. 653. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhodes JM, Potter BJ, Brown DJ, Jewel DP. Serum inhibitors of leukocyte chemotaxis in Crohn′s disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:1327–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross V, Andus T, Caesar I, Rotu M, Scholmerich J. Evidence for continuous stimulation of interleukin - 6 Production in Crohn′s disease. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:514–19. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90098-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katschinski B, Logan RF, Edmond M, Lagman MJ. Smoking and sugar intake are separate but interactive risk factors in Crohn′s disease. Gut. 1988;29:1202–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.9.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thoreson R, Cullen JJ. Pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease: An overview. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:575–85. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayberry JF, Rhodes J, Newcombe RG. Breakfast and dietary aspects of Crohn′s disease. Br Med J. 1978;2:1401–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6149.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamster 1, Souis S, Hannigan A, Kolodkin A. An association between Crohn′s disease, periodontal disease and enhanced neutrophil function. J. Periodontal. 1978;49:475–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1978.49.9.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]