Abstract

Objectives:

To study the prevalence of oral manifestations in HIV-infected patients and to correlate oral manifestations with age, gender, severity, and clinical staging.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty patients of either sex diagnosed as HIV positive were included in the study. The data obtained were analyzed statistically using Fisher's exact test and Chi-square test.

Results:

Among the 50 HIV-infected patients, oral manifestations were found in 40 (80.0%) patients. Thirty (60%) patients were seen in the age range between 31 and 65 years, and 29 (58%) patients were females. Majority of the patients [26 (52%)] were in the clinical staging C, of whom 23 (88.5%) were with manifestations with significant statistical value (P < 0.05). Patients with CD4 count less than 200 had manifestations in 22 (88%) patients. Correlation between reduction in CD4 count and presence of manifestations was significant (P < 0.05). Twenty-eight (80%) patients without antiretroviral therapy (ART) reported with manifestations. Correlation between ART and presence of manifestations was not significant (P = 1.00).

Interpretation and Conclusion:

Oral manifestations are the indicators for the disease progression. Clinical stage C and lower CD4 count may be useful predictors for HIV, with greater prevalence of oral manifestations.

KEY WORDS: Antiretroviral therapy, CD4, human immunodeficiency virus

“The mouth is a window for HIV infection.” Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is a serious disorder of the immune system in which the body's normal defenses against infection break down, leaving it vulnerable to a host of life-threatening infections. The presence of certain oral diseases can be an important tool for identifying persons living with HIV and assessing the relative progression of their disease.[1]

AIDS came into limelight in 1981.[2] The detection of HIV infection for the first time in India was made in April 1986 in the state of Tamil Nadu. Since then, HIV infection has been spreading at an alarming rate.[3] HIV related oral abnormalities are present in 30–80% of HIV-infected individuals. Individuals with unknown HIV status and oral manifestations may suggest possible HIV infection, although they are not diagnostic of infection.[4]

The presence of oral lesion may be an early diagnostic indicator of immunodeficiency and HIV infection, and is a predictor of the progression of HIV disease.[2] Oral lesions of HIV infection are included in various classifications and staging of HIV diseases.[5]

However, most of the studies pertaining to oral manifestations of HIV have been performed mainly in Western countries. In India, only few studies have been reported so far.[6] Therefore, a need was felt to conduct a study to evaluate the oral lesions in HIV-infected individuals.

Materials and Methods

Fifty patients of either sex, with age ranging from 6 to 65 years and diagnosed as HIV positive, were included in the study and comprised the study group. Patients diagnosed as HIV positive by Tridot test were included in the study. HIV patients with trismus were not included in the study. After the clinical examination, investigations were done depending upon the type of the lesion. Depending upon oral manifestations and CD4 cell counts, revised CDC Classification System based clinical staging was done.

Descriptive data that included mean, numbers, and percentage were calculated for each category and used for comparisons. The results were correlated using Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test, and P value <0.05 or less was considered to be significant. Conclusions were drawn based upon the obtained data.

Results

All 50 patients who were included in the study were subjected to clinical examination and the following observations were made.

The age group of the study population ranged from 6 to 65 years, with a male to female ratio of 0.7:1. By occupation, 7 (14%) patients were professionals, 3 (6%) were skilled, 16 (32%) were unskilled, 2 (4%) were students, 21 (42%) were housewives, and 1 (2%) patient was a driver. Mode of transmission was sexual in 48 (96%) patients and maternal-fetal transmission in 2 (4%) patients. Based on CDC classification, clinical staging A was seen in 14 (28%) patients, B in 10 (20%) patients, and C in 26 (52%) patients. Fifteen (30%) patients were under antiretroviral therapy (ART).

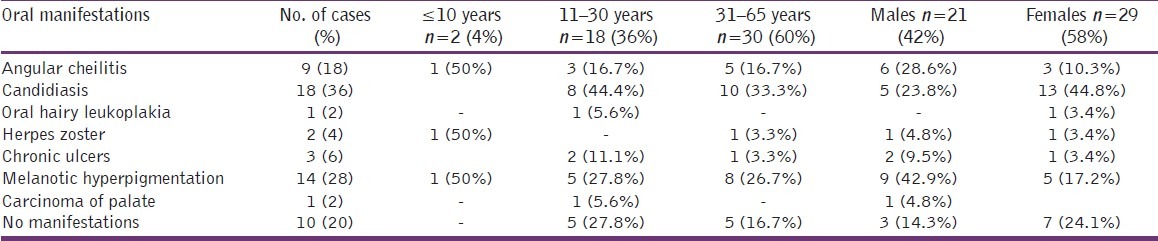

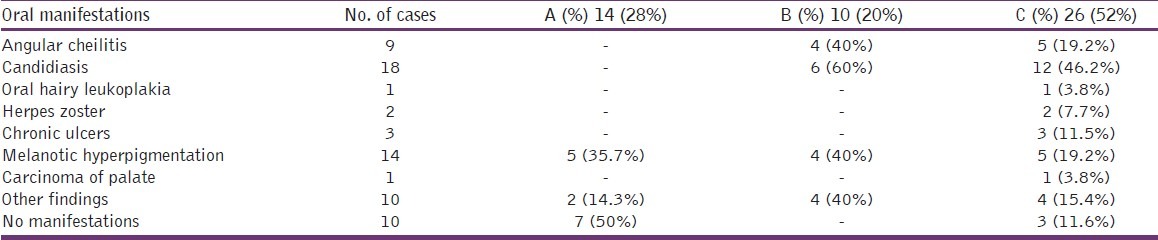

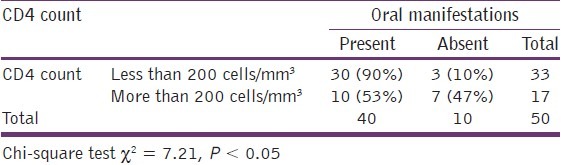

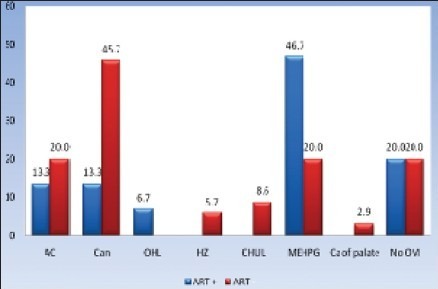

Distribution of oral manifestations according to age, gender [Table 1] clinical staging [Table 2], comparison of oral manifestations with CD4 count [Table 3] and ART [Graph 1] are given in Tables 1–3 and Graph 1 respectively.

Table 1.

Distribution of oral manifestations according to age and gender

Table 2.

Distribution of oral manifestations according to clinical staging

Table 3.

Comparisons of oral manifestations with CD4 count

Graph 1.

ART and oral manifestations

Discussion

HIV-related oral abnormalities are present in 30–80% of HIV-infected individuals.[4] Oral lesions have been shown to be associated with increased risk of progression of HIV disease and are highly predictive markers of severe immune deterioration.[7,8] CD4 lymphocyte cell count is widely used as a marker for HIV-related disease progression.[8]

The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) delayed the onset of AIDS in those patients in whom the HIV infection was already recognized and decreased mortality rates were reported in those patients who already had their HIV progress to AIDS.[9]

Distribution of demographic and clinical data of HIV-infected patients

The present study was conducted on 50 HIV-infected patients with age ranging from 6 to 65 years, with a mean age of 35.8 years for males as compared to 32.2 years for females. The majority of the patients were seen in the age range from 31 to 65 years. Similar observations were made by Anil et al,[10] Majority of the patients in our study were in the age group between 30 and 40 years, which might be due to heterosexual transmission. In our study, 2 (4%) patients were below 10 years of age due to maternal–fetal transmission.

In our study, there were 29 (58%) females and 21 (42%) males. Similar female predominance was noted by Kerdpon et al, in their study.[11] The female predominance observed in our study was in contrast to the observation made by Ranganathan et al,[12] in which male predominance was present.

In our study, by occupation, 21 (42%) patients were housewives, 16 (32%) were unskilled, 7 (14%) were professionals, 3 (6%) were skilled, 2 (4%) were students, and 1 (2%) patient was a driver. Similar observations were made by Kerdpon et al, in their study on south and north Thai patients.[11] Majority of the patients in our study were housewives and unskilled, which may be because of prevalence of increased rate of illiteracy and hence lack of knowledge and awareness regarding transmission, spread, and protection from the disease.

In our study, the mode of transmission was found to be heterosexual in majority of the cases (96%). Similar observations were made by Arendrof et al.[13] The other major mode of transmission was through blood transfusion as noted in studies conducted by Ranganathan et al.[12]

Oral manifestations in HIV patients [Table 1]

The most common manifestation observed in a majority of the 50 HIV-infected patients was candidiasis [67 (54%)] [Figure 1]. Similar observations were made by Sharma et al.[6] Salivary IgA affects the adherence of Candida to buccal epithelial cells in HIV-infected patients who develop oral candidiasis, and serum and salivary IgA decrease. This helps in explaining the strong association between candidiasis and HIV positivity, especially in those who are about to develop full-blown AIDS.[14]

Figure 1.

Pseudomembranous candidiasis

Among the 50 HIV-infected patients, the second most common manifestation observed was melanotic hyperpigmentation in 14 (28.0%) patients, which was similar to the observation made by Arendorf et al. [Figure 3].[13] Melanotic hyperpigmentation may be an early sign of adrenal insufficiency or secondary to medications (ART).[2]

Figure 3.

Melanotic hyperpigmentation

Oral hairy leukoplakia was observed in 1 (2%) patient of our study group, which was considerably less compared to that reported in the studies done by Ranganathan et al.[12] Kolokotronis et al. in their study observed that oral candidiasis and hairy leukoplakia in correlation with immunologic status, as indicated by low circulating CD4 cell counts and the absence of anti-p24 antibodies in serum and the loss of secretory anti-p24 antibodies in subjects with hairy leukoplakia, may constitute the prognostic markers for the progression of HIV infection to AIDS.[15]

Herpes zoster was observed in 2 (4%) patients of our study group [Figure 2]. Similar oral finding was observed by Sharma et al.[6] Herpes zoster in HIV/AIDS patients may be due to an immunosuppression which causes reactivation of latent varicella zoster virus.

Figure 2.

Herpes zoster

Chronic ulcers were observed in 3 (6%) patients of our study group. Similar oral lesions were observed by Arendrof et al.[13] in their study. Joan et al. in their study suggested that changes in cell-mediated immunity, including autoimmunity, are involved in the development of ulcerations.[16]

Squamous cell carcinoma of palate was observed in 1 (2%) patient of our study group [Figure 4]. Similar oral finding was noted by Anil et al.[10] HIV infection may accelerate the development of squamous cell carcinoma, possibly because of impaired immune surveillance.[17]

Figure 4.

Carcinoma of palate

No oral manifestations were observed in 10 (20%) patients of our study group, out of whom 7 (50%) patients belonged to clinical staging A, in which patients will be asymptomatic, and 3 (20%) patients were on highly active anti retroviral therapy (HAART), which has a critical role in the prevention of oral manifestations of HIV, probably because of its role in the reconstitution of the immune system.[9] Similar observations were made by Ranganathan et al.[12]

Distribution of oral manifestations according to age and gender [Table 1]

Majority of the manifestations were observed in the age range of 31–65 years, which may be due to heterosexual transmission. Similar observations were made by Sharma et al.[6]

In our study, candidiasis was observed in 16 (65.1%) females and 11 (52.4%) males. Similar slight female predominance of candidiasis was observed by Sharma et al.[6] In contrast, male predominance was observed by Ranganathan et al.[12] In our study, Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) was observed in 1 (3.4%) patient with female predominance, which is in contrast to the report of Ranganathan et al.[12] in which male predominance was noted.

Herpes zoster was observed in 1 (4.8%) male and 1 (3.4%) female patient in our study group, which is contradictory to the observations made by Sharma et al.[6] In our study, chronic ulcers were observed in 2 (9.5%) male and 1 (3.4%) female patient. Similar type of male predominance was observed by Ranganathan et al.[12]

Melanotic hyperpigmentation was observed in 9 (42.9%) male and 5 (17.2%) female patients in our study group. Similar type of male predominance was noted by Sharma et al.[6] In our study, no oral manifestations were observed in 7 (24.1%) female and 3 (14.3%) male patients.

Distribution of oral manifestations according to clinical staging [Table 2]

Majority of the patients with manifestations were seen in stage C, which is similar to the observations made by Sharma et al.[7] In our study, the increased incidence of manifestations in stage C, in which CD4 count is less than 200, is indicative of more lymphocytes’ destruction.

Distribution of oral manifestations according to anti retroviral therapy (ART) [Graph 1].

Out of 50 HIV-infected patients, 15 (30%) received ART and 35 (70%) did not.

Thirty-five patients were without ART, out of whom 28 (80%) were with manifestations. Candidiasis was observed in 23 (65.7%) patients, 2 (5.7%) patients had herpes zoster, 3 (8.6%) patients had chronic ulcers, and 1 (2.9%) patient had carcinoma of palate. Similar oral findings were observed by Umadevi et al.[18] in which oral candidiasis was seen in majority of the patients, followed by melanotic hyperpigmentation in patients without ART.

The common manifestations observed in patients receiving ART were melanotic hyperpigmentation in 7 (46.7%) patients and candidiasis in 4 (26.6%) patients. These observations are similar to those of Umadevi et al.[18] Melanotic hyperpigmentation was the most common manifestation observed, which might be secondary to medications.[2]

With ART, less manifestation was observed, which might be due to suppression of viral replication, allowing for partial restoration of the immune system, and protection against opportunistic pathogens.[18]

Comparison of oral manifestations with clinical staging

More manifestations were found in stages B and C and the differences were statistically significant between A and B, and A and C (Fisher's exact test, P < 0.05). But no statistically significant difference was found between B and C (Fisher's exact test, P = 0.30). These differences in oral manifestations observed in our study may be due to increase in immunosuppression.

Comparison of oral manifestations with CD4 count

Correlation between reduction in CD4 count and presence of manifestations is significant (P < 0.05) and this is due to altered immune status indicative of more lymphocytes’ destruction. Thus, CD4 count could be considered as a marker for HIV-related disease progression.

Comparison of oral manifestations with ART [Graph 1]

Correlation between ART and presence of manifestations was not statistically significant (P = 1.00) in our study, which may be because of less number of patients receiving ART. This observation was found to be similar to that reported in a study conducted by Umadevi et al.[18] In contrast, correlation between ART and presence of manifestations was statistically significant in a study done by Anwar et al., which might be due to suppression of viral replication and protection against opportunistic infections.[9]

Conclusions

Based on the clinical examination and statistical analysis of data collected, the following conclusions can be drawn from the present study. Majority of the patients in our study were seen in the age range between 31 and 65 years, with common heterosexual mode of transmission. Female predominance was present, with male to female ratio of 0.7:1. The common oral manifestation observed was candidiasis and is a significant oral indicator of immunosuppression in HIV infection. More number of oral manifestations was seen in patients in their 3rd to 6th decade. Majority of oral manifestations were found in female patients with high spouse mortality, indicating sexual transmission of the disease. Majority of the patients were seen in patients with clinical staging C, which indicates severe immune deterioration and disease progression. Low level of CD4 counts was associated with greater prevalence of oral manifestations, and thus lower CD4 count is a useful predictor for HIV. Fewer oral manifestations were present in patients on HAART, and thus early treatment with HAART helps in improving the patient's quality of life by reconstituting the immune system. Melanotic hyperpigmentation was the most common manifestation in patients with HAART, which is secondary to drugs.

Our study involved a small sample size and the results of our study need to be confirmed in larger longitudinal population studies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Agabian N, Buchbinder S, Canchola A, De Souza YG, Greenblatt R, Greenspan D, et al. The mouth as a window on HIV. Sci Comm. 2000:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar NR, Bose TC, Balan A. Oral manifestations in HIV infection. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2006;18:11–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redkar VE, Redkar SV. Epidemiological features of human immunodeficiency virus infection in rural area of western India. J Assoc Physicians India. 1999;47:263–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reznik DA. Perspective oral manifestations of HIV disease. Top HIV Med. 2005;13:143–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiboski CH. Epidemology of HIV-related oral manifestations in women: A review. Oral Dis. 1997;3:S 18–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1997.tb00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma G, Pai KM, Suhas S, Ramapuran JT, Doshi D, Anup N. Oral manifestations in HIV/AIDS infected patients from India. Oral Dis. 2006;12:537–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Begg MD, Lamster IB, Panageas KS, Lewis MD, Phelan JA, Garbic JT. A prospective study of oral lesions and their predictive value for progression of HIV disease. Oral Dis. 1997;3:176–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1997.tb00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glick M, Muzyka BC, Lurie D, Salkin LM, Camden NJ. Oral manifestations associated with HIV-related disease as markers for immune suppression and AIDS. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:344–9. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tappuni AR, Fleming GJ. The effect of antiretroviral therapy on the prevalence of oral manifestations in HIV-infected patients: A UK study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:623–8. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.118902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anil S, Challacombe SJ. Oral lesions of HIV and AIDS in Asia: An overview. Oral Diseases. 1997;3(Supp 1):S36–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1997.tb00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerdpon D, Pongsiriwet S, Pangsomboon K, Lamaroon A, Kampoo K, Sretrirutchai S, et al. Oral manifestations of HIV infection in relation to clinical and CD4 immunological status in Northen and Southern Thai patients. Oral Diseases. 2004;10:138–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1601-0825.2003.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ranganathan K, Reddy BV, Kumaraswamy N, Solomon S, Viswanathan R, Johnson NW. Oral lesions and conditions associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection in 300 south Indian patients. Oral Dis. 2000;6:152–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2000.tb00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arendorf TM, Bredekamp B, Cloete CA, Sauer G. Oral manifestations of HIV infection in 600 South African patients. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:176–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1998.tb01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molinari JA, Glick M. Infectious diseases. In: Greenberg MS, Glick M, editors. Burket's oral medicine, diagnosis and treatment 2003. 10th ed. Ontario: BC Decker, Hamilton; 2003. pp. 539–56. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolokotronis A, Kioses V, Antoniades D, Mandraveli K, Doutsos I, Papanayotou P, et al. Immunologic status in patients infected with HIV with oral candidiasis and hairy leukoplakia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78:41–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phelan JA, Eisig S, Freedman PD, Newsome N, Klein RS, Flushing Major aphthous-like ulcers in patients with AIDS. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:68–72. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90524-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE, editors. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 2nd ed. Pennsylvania: Saunders Philadelphia; 2002. pp. 217–49. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umadevi KMR, Ranganathan K, Pavithra S, Hemalatha R, Saraswathi TR, Kumarswamy N, et al. Oral lesions among persons with HIV disease with and without highly active antiretroviral therapy in southern India. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]