Abstract

A patient attending for treatment of a restorative nature may present for a variety of reasons. The success is built upon careful history taking coupled with a logical progression to diagnosis of the problem that has been presented. Each stage follows on from the preceding one. A fitting treatment plan should be formulated and should involve a holistic approach to what is required.

KEY WORDS: Diagnosis, history, holistic, restorative, treatment plan

The purpose of dental treatment is to respond to a patient's needs. Each patient, however, is as unique as a fingerprint. Treatment therefore should be highly individualized for the patient as well as the disease.[1]

Treatment Planning

It is a carefully sequenced series of services designed to eliminate or control etiologic factor.[2]

It is the schedule and sequence of the treatment, which have been outlined.[3]

It is created as a response to the problem list.[4]

It means developing a course of action that encompasses the ramifications and sequeale of treatment to serve patients’ needs.[5]

It is the blueprint for case management.[6]

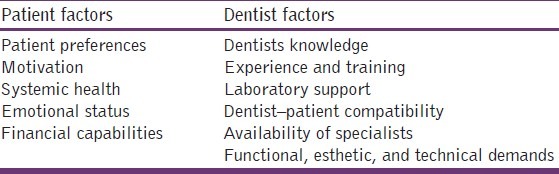

The order of the general treatment plan has as its basis an understanding of the disease processes and their relationship to each other. Fundamental is that the diagnosed lesion be considered in context with its host, the patient, and the total environment to which it is subjected. Careful weighing of all information will lead to an authoritative opinion regarding treatment. So, a sound treatment plan [Table 1] depends on thorough patient evaluation, dentist expertise, understanding the indications and contraindications, and prediction of patient's response to treatment. An accurate prognosis for each tooth and the patient's overall dental health is central to a successful treatment plan.

Table 1.

Factors affecting treatment plan

Development of treatment plan for a patient consists of four steps:

Examination and problem identification

Decision to recommend intervention

Identification of treatment alternatives

Selection of the treatment with patient's involvement.[2]

When the database (information) is gathered, three stages must be established:

Generation of the problem list (ranking the order of problems)

Tentative treatment plan for each of the problems

Synthesis of the tentative treatment plan into a unified detailed treatment plan.[7]

Problem List

The problem list is a summary listing of the patient's complaints, lesions, and conditions that warrant additional diagnostic evaluation or treatment. The problem list is organized by the priority of the problems in the judgment of the clinician. This is usually in the sequence of the chief complaint, current medical conditions, general dental problems, and specific dental lesions.[8]

Even when modification is necessary, the dentist is ethically and professionally responsible for providing the best level of care possible. A treatment plan is not a static list of services. Rather, it is a multiphase and dynamic series of events. Its success is determined by its suitableness to meet the patient's initial and long-term needs. Treatment planning should allow for re-evaluation and be adaptable to meet the changing needs, preferences, and health conditions of the patient.[2]

Order of treatment

Operative treatment generally proceeds from the most to the least involved teeth.

Treatment of the chief complaint of dental pain will of course take precedence.

Certain functional and esthetic considerations may be dealt with early in the treatment plan when indicated (broken teeth, even though not painful, will call for some treatment to relieve the patient of the discomfort of sharp margins).

Sensitive teeth and areas of food impaction may also be treated early. Stability of the occlusion should be assured before proceeding with cast and esthetic crowns.

Factors like operator's schedule and his experience will alter the planned order of procedure.[9]

Treatment plan sequencing

It is the process of scheduling the needed procedures into a time frame. Proper sequencing is a critical component of a successful treatment plan. Complex treatment plans often should be sequenced in phases, including an urgent phase, control phase, re-evaluation phase, definitive phase, and maintenance phase.[10] For most patients, the first three phases are accomplished as a single phase. Generally, the concept of greatest need guides the order in which treatment is sequenced. This concept dictates that what the patient needs is performed first.

Urgent phase

The urgent phase of care begins with a thorough review of the patient's medical condition and history. So, a patient presenting with swelling, pain, bleeding, or infection should have these problems managed as soon as possible and certainly before initiation of subsequent phases.

Control phase

It is meant to

eliminate active disease such as caries and inflammation;

remove conditions preventing maintenance;

eliminate potential causes of disease, and

begin preventive dentistry activities.[2]

This includes extractions, endodontics, periodontal debridement and scaling, occlusal adjustment as needed, caries removal, replacement/repair of defective restorations such as those with gingival overhangs, and use of caries control measures.[11] The goals of this phase are to remove etiologic factors and stabilize the patient's dental health.

Re-Evaluation phase

The holding phase is the time between the control and definitive phases that allows for resolution of inflammation and time for healing. Home care habits are reinforced, motivation for further treatment is assessed, and initial treatment and pulpal responses are re-evaluated before definitive care is begun.

Definitive phase

After the dentist reassesses initial treatment and determines the need for further care, the patient enters the corrective or definitive phase of treatment. Sequencing operative care with endodontic, periodontal, orthodontic, oral surgical, and prosthodontic treatment is essential.

Maintenance phase

This includes regular recall examinations that:

may reveal the need for adjustments to prevent future breakdown, and

provide an opportunity to reinforce home care.

The frequency of re-evaluation examinations during the maintenance phase depends in large part on the patient's risk for dental disease:

A patient who has stable periodontal health and a recent history of no caries should have longer intervals (e.g. 9–12 months or longer) between recall visits.

Those at high risk for dental caries and/or periodontal breakdown should be examined much more frequently (e.g. 3–4 months).

Actual caries risk is the extent to which a person at a particular time runs the risk of developing carious leision.[12]

Quadrant Dentistry

This approach should be included in the treatment plan. It reduces the number of times local analgesics is used, makes maximum use of the time available, and is economically beneficial.[13]

Documentation

Documentation in the context of health care refers to the production of a physical record that contains the pertinent information related to the diagnosis and treatment of the patient.

Features of Ideal Patient Documentation System

Allow quick and easy data entry

Allow quick and easy data retrieval

Should be comprehensive

Should be brief

Should be clear

Should be made to use the data conveniently

Should be easily expandable

Should be versatile

Should be efficient by quickly conveying complex information

Should be economical

Should be educational by reinforcing diagnostic, treatment planning, and patient management principles.[8]

Charting

Though various formats are available for recording a patient's dental condition, an acceptable charting system should conform to certain standards. The charts should be

uncomplicated,

comprehensive,

accessible, and

current.[14]

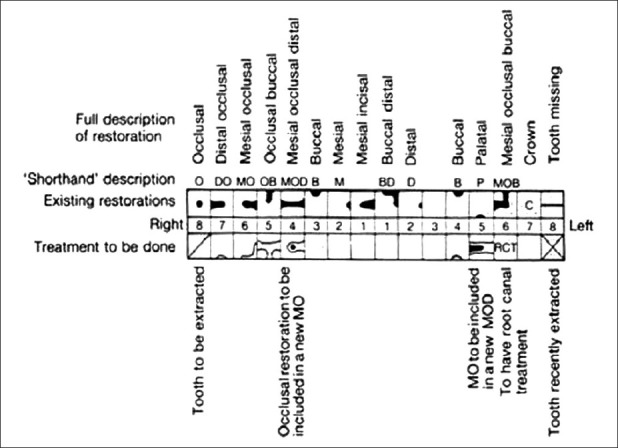

Conservative Charting

This includes caries and existing restoration. This represents the dentition when viewed from in front of the patient, so that the teeth that are on the right side of the page are on the patient's left side and vice versa. The convention is that the horizontal line between the upper and lower teeth represents the tongue, so that the lingual or palatal surfaces are those nearest to this line, and the buccal or labial surfaces are those at the top of the top row and the bottom of the bottom row. The marks on the posterior teeth [Figure 1] divide the tooth into occlusal, mesial, distal, buccal, and lingual surfaces, and the same applies to the anterior teeth except that there is no occlusal surface.[15]

Figure 1.

This chart does not represent the size of the lesion or restoration

Interdisciplinary Considerations

Endodontics

All teeth to be restored with large or cast restoration should have a pulpal/periapical evaluation. If indicated, they should have endodontic treatment before restoration is complete. For the endodontically inadequate filled tooth, oral fluids exposed to the fill should be evaluated before restorative therapy is initated.[16]

Periodontics

Generally, periodontal treatment should precede operative care, since it creates a more desirable environment for performing operative treatment. Any teeth requiring restorations that may encroach on the biologic width of periodontium should have appropriate crown-lengthening surgical procedures performed before the final restoration is placed. Usually, a minimum of 6 weeks is required following the surgery before final restorative procedures.

Orthodontics

All teeth should be free of caries before orthodontic banding.

Oral surgery

In most instances, impacted, unerupted, and hopelessly involved teeth should be removed before operative treatment. Also, soft tissue lesions, complicating exostoses, and improperly contoured ridge areas should be eliminated or corrected before final restorative care.[2]

Occlusion

The design of the restored tooth surface can have important effects on the number and location of occlusal contacts and must take into consideration both static and dynamic relationships. Occlusal adjustments should be considered before the definitive restoration phase.[17].

Fixed prosthodontics

Preferably, restorations should be completed before placing a cast restoration.

Removable prosthodontics

Tooth preparation and restorations should allow for the design of the removable partial denture, i.e., it should correlate with the design of the contemplated removable prosthesis.[18]

Treatment Plan Approval

Informed consent has become an integral part of modern day dental practice.[19] One aspect of informed consent is to provide the patient with the necessary information about the alternative therapies available to manage their oral conditions.

Alternatives presented

↓

Advantages / disadvantages of each discussed

↓

Risk associated with each alternative therapy

↓

Cost

(Many times a reasonable alternative is not to intervene but instead to monitor the condition.)

Once the dentist is sure about the above, then treatment can proceed.[20,21]

Conclusion

Many problems encountered during treatment are directly traceable to factors overlooked during the initial examination and data collection. It is important that the patient's mouth is not seen merely as a long list of items, each of which requires completion before the next one can be started.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.McGivney GP, Castleberry DJ. In: McCracken's Removable Partial Prosthosdontics. 8th ed. Delhi: CBS Publishers and Distributors; 1989. Diagnosis and treatment planning; pp. 209–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shugars DA, Shugars DC. Patient Assessment, Examination and Diagnosis, and Treatment Planning. In: Roberson TM, Heymann HO, Swift EJ, editors. Sturdevant's art and science of operative dentistry. 4th ed. USA: Mosby; 2002. pp. 389–428. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilmore HW, Lund MR, Bales CDJ, Vernetti JP. In: Operative Dentistry. 4th ed. New Delhi: B.I. Publications Pvt. Ltd; 1994. The patient record, diagnosis and treatment planning; pp. 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staley RN. Orthodontic Diagnosis and Treatment Planning. In: Bishara SE, editor. Textbook of Orthodontics. USA: WB Saunders Company; 2001. pp. 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franco RL, Ortman LF. Diagnosis and Treatment Planning. In: Winkler S, editor. Essentials of complete Denture Prosthodontics. 2nd ed. New Delhi: A.I.T.B.S Publishers and Distributors; 1996. pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carranza FA., Jr . The Treatment Plan. In: Carranza FA Jr, Newman MG, editors. Clinical Periodontology. 8th ed. Bangalore: Harcourt Asia Pvt. Ltd; 1999. pp. 399–400. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Profitt WR, Ackerman JL. Diagnosis and Treatment Planning in orthodontics. In: Graber TM, Swain BF, editors. Orthodontics current principles and techniques. 1st ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 1991. pp. 3–100. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman GC. Documentation. In: Coleman GC, Nelson JF, editors. Principles of Oral Diagnosis. USA: Mosby-Yearbook; 1993. pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charbeneau GT. In: Principles and Practice of Operative Dentistry. 3rd ed. Bombay: Varghese Publishing House; 1989. Examination, Diagnosis and Treatment Planning; pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fasbinder DJ. Treatment Planner's toolkit. Gen Dent. 1999;47:35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberson TM, Lundeen TF. Cariology: The lesion, Etiology, Prevention and Control. In: Roberson TM, Heymann HO, Swift EJ, editors. Sturdevents’ Art and Science of Operative Dentistry. 4th ed. USA: Mosby; 2002. pp. 63–132. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krasse B. Caries Risk. Chicago: Quintessence; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curzon ME, Roberts JF, Kennedy DB. In: Kennedy's Paediatric Operative Dentistry. 4th ed. USA: Wright Publishers; 1996. Treatment Planning; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Dental Patient record: Strucure and function guidelines. Chicago: American Dental Association; 1987. Amercian Dental Association. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kidd EA, Smith BGN, Pickard HM. In: Pickard's Manual of Operative Dentistry. 7th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. Making Clinical Decisions; pp. 28–48. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madison M, Wilcox LR. An evaluation of coronal microleakage in endodontically treated teeth. Part 3: In vivo study. J Endod. 1998;14:455–8. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(88)80135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sturdevent JR, Lundeen TF, Sluder TB., Jr . Clinical Significance of Dental Anatomy, Histology, Physiology, Operative Dentistry. 4th ed. USA: Mosby; 2002. pp. 13–62. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilder AD, Jr, Ritter AV, Roberson TM, May KN., Jr . Complex Amalgam Restorations. In: Roberson TM, Heyman HO, Swift EJ, editors. Sturdevent's Art and Science of Operative dentistry. 4th ed. USA: Mosby; 2002. pp. 763–97. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sfikas PM. Informed consent and the Law. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1471–3. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christensen GJ. Educating Patients About Dental Procedures. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:371–2. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christensen GJ. Educating Patients: A New necessity. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124:86–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1993.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]