Abstract

Stroke is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. While tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) remains the only FDA approved treatment for ischemic stroke, clinical use of tPA has been constrained to roughly 3% of eligible patients because of the danger of intracranial hemorrhage and a narrow 3h time window for safe administration. Basic science studies indicate that tPA enhances excitotoxic neuronal cell death. In this review, the beneficial and deleterious effects of tPA in ischemic brain are discussed along with emphasis on development of new approaches towards treatment of patients with acute ischemic stroke. In particular, roles of tPA induced signaling and a novel delivery system for tPA administration based on tPA coupling to carrier red blood cells will be considered as therapeutic modalities for increasing tPA benefit/risk ratio. The concept of the neurovascular unit will be discussed in the context of dynamic relationships between tPA-induced changes in cerebral hemodynamics and histopathologic outcome of CNS ischemia. Additionally, the role of age will be considered since thrombolytic therapy is being increasingly used in the pediatric population, but there are few basic science studies of CNS injury in pediatric animals.

Keywords: stroke, tissue plasminogen activator, cerebral ischemia, pediatric, neurovascular unit, signaling

Background

The Word Health Organization defines stroke as “rapidly developing signs of focal or global disturbance of cerebral function, with symptoms lasting 24h or longer leading to death, with no apparent cause other than that of vascular origin”. Stroke is the third leading cause of morbidity and mortality after heart disease and cancer. Surviving stroke victims often face serious long-term disability and constitute a significant familial and societal economic burden. Stroke can be classified broadly into ischemic or hemorrhagic, with the former comprising 80% of cases. Ischemic stroke, in turn, can be further subclassified as thrombotic or embolic in origin. Thrombotic stroke occurs when a clot forms in an artery located within the brain whereas an embolic stroke results from a clot formed elsewhere in the body that is subsequently transported to the brain. Hemorrhagic stroke results from the disruption of vascular integrity or aneurysm sufficient to cause bleeding within the brain.

Generally speaking, 3 major approaches have been used in the treatment of acute stroke: neuroprotection, thrombolysis, and clot removal. To date, neuroprotection has been largely unsuccessful with the inability to translate potentially novel therapeutics found to be efficacious in animal models to the clinical arena (Lapchak and Araujo 2007; Fisher and Bastan 2008). In contrast, thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and mechanical removal of clot have both been approved by the FDA for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Based on studies (NINDS Study Group, 1995) that treatment within 3h of stroke symptom onset resulted in an increased number of patients with good outcome and a reduction in the proportion of patients with disability or death at 3 months, intravenous tPA remains the current standard of care for treatment of acute ischemic stroke within 3h of the ischemic event. Recent studies, however, have indicated that the time window for administration maybe safely extended from 3 to 6h post onset of the ischemic event (Hacke et al 1995; Lansberg et al 2009).

However, in addition to its salutary role in reperfusion, there is a growing body of scientific investigation indicating that tPA also exhibits deleterious action within the brain. Indeed, the original findings of the NINDS noted that the use of tPA was associated with an approximate 10% increase of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) (NINDS Study Group, 1995). As a result, clinical use of tPA in actual practice has been constrained to only roughly 3% of those eligible for such therapy (Lapchak and Araujo 2001; Lapchak 2002). Importantly, there is also a significant propensity for cerebrovascular thrombosis to recur. As a result, hospitalization is often recommended even in stable patients to preserve the option of timely re-administration of intravenous tPA, if necessary to treat reocclusion, an approach fraught with the potential for ICH (Fisher and Bastan 2008).

Studies in animal models demonstrate that endogenous tPA may increase the volume of injured tissue after stroke (eg in tPA null mice), provoke ICH, and exacerbate excitotoxic neuronal cell death by enhancing signaling through the NMDA glutamate receptor (Wang et al 1998, Nicole et al 2001). Although various modifications have been made to recombinant tPA, with the intent of improving its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, none have mitigated in the risk of ICH.

In this review, the beneficial and deleterious effects of tPA in the ischemic brain are discussed along with an emphasis on development of new approaches towards treatment of patients with acute ischemic stroke. In particular, the roles of tPA induced signaling and novel delivery systems for tPA administration based on coupling the drug to carrier red blood cells (RBC) will be considered as new approaches to increase its benefit/risk ratio. Additionally, the role of age will be considered as thrombolytic therapy is being increasingly used in the pediatric population, but there have been few basic science studies that investigate potential differences in the effect of CNS injury and its treatment as a function of age.

tPA in CNS Physiology

tPA and urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) are serine proteases that are normally present in both the intravascular space as well as the brain parenchyma. They cleave the zymogene plasminogen to produce the active serine protease plasmin (Yepes et al 2008). In the intravascular compartment, blood clots are formed from the aggregation of activated platelets and formation of fibrin meshwork from fibrinogen. Fibrinolysis is achieved by plasmin generated primarily through the action of tPA. tPA is expressed in endothelial cells, neurons, and glia (Yepes et al 2009). The principal source of tPA in the intravascular space is the endothelial cell, from which it is released in the presence of fibrin to help preserve patency of the vasculature (Figure 1). Termination of tPA catalytic activity in plasma is produced by binding of serine protease (serpin) inhibitors, chiefly the PA inhibitor I (PAI-1) (Van Mourik et al 1992). Inactive tPA/PAI-1 complexes are cleared from the circulation by low density receptor-related protein (LRP) (Orth et al 1992). A neuronal specific inhibitor of tPA, neuroserpin, is the primary modulator of tPA activity in the CNS (Osterwalder et al 1996).

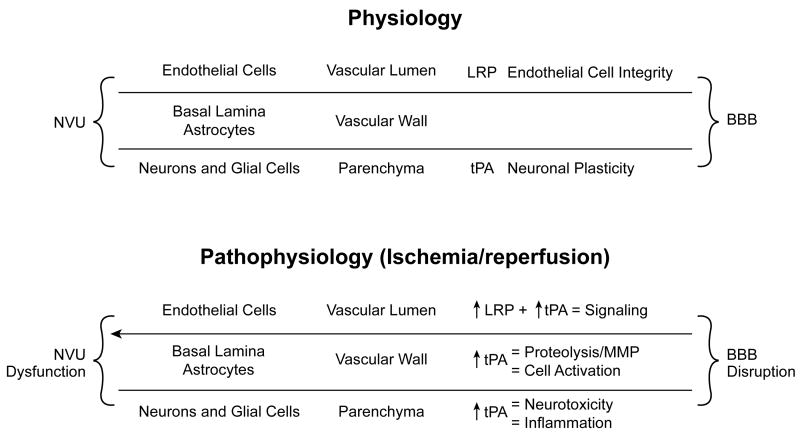

Figure 1.

Interactions between tPA and LRP in the physiological and pathophysiological function of the neurovascular unit.

The neurovascular unit (NVU) is a dynamic structure consisting of endothelial cells, perivascular neurons and astrocytes, and the basal lamina (Abbott et al 2006; del Zoppo and Mabuchi 2003; Lo et al 2003). An important function of the NVU is to form a barrier known as the blood brain barrier (BBB), which regulates the bidirectional passage of substances between the brain and the intravascular space (Figure 1). The BBB function is determined mainly by the presence of tight junctions between endothelial cells and by the interaction between perivascular astrocytes and the basement membrane. Astrocytic LRP has a central role maintaining the integrity of the interaction between perivascular astrocytes and the basal lamina (Polavarapu et al 2007) (Figure 1). Interaction of tPA with LRP plays a role in regulating cerebrovascular tone (Nassar et al 2004; Akkawi et al 2006) and permeability of the NVU under nonischemic conditions (Yepes et al 2003). In the absence of ischemia, production and trans NVU transport of tPA is limited and readily constrained by PAI-1 and neuroserpin (Figure 1). After an ischemic event, however, tPA transport across the BBB can overwhelm the “buffering capacity” of serpins, resulting in pathologic action of tPA within the CNS and disruption of barrier function. Early after the onset of an ischemic insult, there is increased tPA activity around the NVU associated with the development of cerebral edema (Yepes et al 2003) (Figure 1). Cerebral ischemia also upregulates LRP experession in the abluminal side of the NVU and the deleterious action of tPA on the NVU is mediated by interaction with LRP (Yepes et al 2003; Polavarapu et al al 2007) (Figure 1). Furthermore, pro-inflammatory factors and cytokines may sensitize the CNS parenchyma to injurious effects of tPA and plasmin. For example, the interaction between tPA and LRP leads to an increase in MMP-9 expression and activity associated with the development of ischemic edema (see below) (Figure 1).

tPA in CNS Pathology of BBB Function

Degradation of the BBB occurs early after onset of ischemia, enabling transport of substances and passage of fluid which contributes to edema and hemorrhagic transformation (Figure 1). In humans administered tPA for treatment of acute ischemic stroke, an increased BBB permeability was observed (Kidwell et al 2008), indicating that the therapeutic application of this thrombolytic may, itself, have unintended deleterious actions. tPA may contribute to enhanced BBB permeability in the setting of stroke through interactions with multiple signaling pathways. For example, in a rat model of embolic stroke tPA has been observed to mediate ischemia induced increase in BBB permeability through enhanced expression and activity of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) (Aoki et al 2002; Lee et al 2007) (Figure 1). tPA mediated increased BBB permeability may occur both in an LRP or platelet derived growth factor but non LRP dependent manner (Yepes et al 2003; Su et al 2008). More recently, a model has been proposed wherein tPA interacts with NF-κB, MMP-9, and iNOS to increase BBB permeability during ischemia (Yepes et al 2009). In this model, tPA is envisioned as inducing phosphorylation of p65, an indicator of NF-κB activation, in an LRP dependent manner, which, in turn, increases expression of iNOS and MMP-9, both of which are known to increase BBB permeability (Yepes et al 2009). Release of uPA has also been observed to occur in an LRP dependent manner after global cerebral hypoxia/ischemia in the piglet, which subsequently induces release of the ERK isoform of mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) to contribute to histopathologic changes such as neuronal cell necrosis, hemorrhage, and edema (Armstead et al 2008).

Neurotoxicity of tPA

Most studies indicate that tPA is neurotoxic (Figure 1), though some results have been variable. For example, ischemia induces an increase in tPA activity associated with cell death (Wang et al 1998) and the development of cerebral edema (Yepes et al 2003). Some of these deleterious effects of tPA equally have been observed in acute stroke patients (Kidwell et al 2008). Treatment with PAI-1 (Tsirka et al 1995), or neuroserpin (Yepes et al 2000) are neuroprotective in animal models of stroke, additionally supportive of the neurotoxicity of tPA. Some studies, however, have alternatively observed beneficial outcome with tPA (Kilic et al 1999; Meng et al 1999; Tabrizi et al 1999). Some of these discrepancies may relate to timing (tPA beneficial early, but detrimental when administered later after stroke onset) (Jiang et al 2000) or to infarct size, where smaller infarct predicts better outcome (Nagai et al 2002).

A link between tPA and glutamatergic neurotransmission has been made in that injection of kainic acid into the hippocampus is associated with cell death in wild type but not tPA null mice (Tsirka et al 1995). Other work has indicated that tPA cleaves the NR-1 subunit of NMDA to increase the influx of calcium (Nicole et al 2001; Fernandez-Monreal et al 2004), though subsequent studies suggest an interaction with the NR2B subunit of NMDA instead (Pawlak et al 2005). Regardless of the mechanism of action, it is widely accepted that tPA interacts with glutamate receptors, which are important mediators of excitotoxicity in ischemic stroke. For example, tPA is thought to control NMDA-dependent NO synthesis in an LRP dependent process and that this effect is critical for excitotoxic neuronal cell loss (Backsai et al 2000; Parathath et al 2006).

tPA mediated signaling, cerebral hemodynamics, and outcome as an emerging area in CNS ischemia

Activation of NMDA receptors elicits cerebrovasodilation, which may represent one mechanism for the coupling of local metabolism to blood flow (Faraci and Heistad 1998). More recently, it was observed that tPA is critical for the full expression of the flow increase evoked by activation of the mouse whisker barrel cortex (Park et al 2008). In particular, tPA was found to promote NO synthesis during NMDA receptor activation by modulating the phosphorylation state of nNOS (Park et al 2008). These findings suggest that tPA is a key factor in linking NMDA receptor activation to NO synthesis and functional hyperemia. Translationally, functional hyperemia is attenuated in Alzheimer’s Disease patients and in mouse models of the disease (Iadecola 2004; Niwa et al 2000), along with decreased tPA activity (Melchor et al 2003). Therefore, impaired hyperemia due to diminished activity of tPA-NMDA receptor axis may be crucial to cognitive outcome in the setting of Alzheimer’s Disease and neurovascular dysregulation following cerebral ischemia (Park et al 2008), where tPA expression has been observed to be decreased transiently by some investigators (Hosomi et al 2001). Nonetheless, in a non-stroke model of CNS injury, fluid percussion brain injury (FPI), endogenous upregulation of tPA contributes to impaired NMDA receptor-mediated cerebrovasodilation post insult (Armstead et al 2005a). Preliminary studies indicate that this results primarily from an upregulation of the JNK isoform of mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), with a more minor role for ERK MAPK upregulation (Armstead et al 2009c). MAPK, a family of at least three kinases, ERK, p38, and JNK, is one of the most distal signaling systems contributory to vascular tone (Laher and Zhang, 2001) and is thought to be critically important in cerebral hemodynamics after pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Armstead et al 2009a). Thus, tPA may either contribute to functional hyperemia in the uninjured state or oppose it in the setting of CNS pathology. In the latter case, NMDA induced pial artery dilation is reversed to vasoconstriction after FPI in the piglet (Armstead 2000). Since autoregulatory pial artery dilation during hypotension is similarly reversed to vasoconstriction after FPI (Armstead 1999) while the NMDA antagonist MK 801 prevented such impairment, these translationally relevant data indicate that this excitatory amino acid contributes to autoregulatory cerebrovascular dilation during hypotension (Armstead 2002). Taken together, then, tPA-mediated impairment of NMDA cerebrovasodilation via JNK MAPK upregulation results in disturbed autoregulation in the setting of TBI (Armstead et al 2005a; 2009c).

At the level of the NVU, tPA can act directly on the vasculature (Nassar et al 2004) to induce hemodynamic alterations that ultimately limit perfusion of the ischemic area despite restoration of vessel patency (Kilic et al 2001). The effect of tPA on vascular tone may result from direct interaction with vascular smooth muscle cells to which it signals via the integrin αvβ3 to elicit vasoconstriction in a non proteolytic manner (Akkawi et al 2006). tPA and uPA signaling mediation by integrin αvβ3 may also influence cerebrovascular tone through inhibition of important vasodilator stimuli such as autoregulation during hypotension and hypercapnia following global cerebral hypoxia/ischemia (Armstead et al 2005b; Kiessling et al 2009a). Signaling is terminated through binding of PAI-1 by tPA, internalization of the integrin-tPA-PAI-1 ternary complex via LRP mediated endocytosis and dissociation of tPA-PAI-1 from the integrin (Akkawi et al 2006).

Plasminogen activators may actually interact with diverse signaling systems to modulate cerebral hemodynamics in the setting of CNS injury. For example, cerebral hypoxia/ischemia causes upregulation of tPA and uPA, which impair cerebrovasodilation in response to hypercapnia and hypotension in an LRP and ERK MAPK dependent manner in piglets (Armstead et al 2008). In the same studies where considerable uPA and ERK MAPK expression was detected in neurons, there was also marked histopathology after cerebral hypoxia/ischemia (Armstead et al 2008). These observations support the concept that plasminogen activators act at the level of the neurovascular unit to impair reactivity to vasoactive stimuli and that overall outcome relates to complex interactions between the vascular compartment and the neuron. However, vasodilator responses to isoproterenol were unchanged after hypoxia/ischemia, indicating that plasminogen activator impairment of cerebrovascular reactivity was not an epiphenomenon. Preliminary data from a more translationally relevant animal model of CNS injury, photothrombosis, indicate that both endogenous and exogenously administered tPA impairs cerebrovasodilation to hypercapnia and hypotension via JNK, but not ERK, MAPK upregulation in the piglet (Kiessling et al 2009b). Alternatively, plasminogen produced neuronal injury in rat slices in culture and in a model of intracranial hemorrhage via ERK, but not p38 MAPK, while JNK MAPK might have been protective (Fujimoto et al 2008). Others have suggested that MMP upregulation observed to occur after focal cerebral ischemia (Tsuji et al 2005) may contribute to the dysfunction of the neurovascular unit (Lo et al 2004). These complex interactions between plasminogen activators and diverse signaling systems in focal, global, and hemorrhagic animal models of CNS injury suggest clinical presentations likely result from a highly heterogenous series of interrelated spatially and temporally regulated mechanistic pathways. Recognition that CNS injury may not be generic and homogenous suggests that design of therapeutics for treatment of CNS ischemic disorders should consider signal transduction mechanisms and etiology to effect improved clinical outcome.

Contemporary strategies used to increase benefit/risk ratio of thrombolytic therapy

Several avenues have been considered to increase the benefit/risk ratio of clinical critical care pathways currently used for thrombolytic therapy of acute ischemic stroke. One is to extend the time window for thrombolysis through development of newer more durable thrombolytics, such as alteplase and desmoteplase (Paciaroni et al 2009). However, these newer formulations do not effectively alter the side effect profiles that depend on proteolysis but simply extend the period of risk (Fisher and Bastan 2008; Meretoja and Tatlisumak 2008). Alternatively, consideration has been given towards the combination of intra-arterial with the traditional intra-venous administration of tPA, which may decrease toxicity, although initial results have been unremarkable (Fisher and Bastan 2008). Similar no improvement of benefit/risk has been provided by novel neuroprotectants, such as the free-radical scavenger NXY-059 (Shuaib et al 2007; Fisher and Bastan 2008). Use of mechanical clot removers are associated with the potential for vascular puncture and intracranial hemorrhage, and have no direct effect on secondary embolization to smaller vessels (Fisher and Bastan 2008).

Combination therapy has been studied in models of focal and global cerebral ischemia to reduce the neurovascular complications of tPA. For example, co-administration of the MMP-9 inhibitor minocycline with tPA decreased incidence of hemorrhage, improved neurologic outcome and decreased mortality in a rat suture occlusion model of focal cerebral ischemia (Machado et al 2009). Similarly, in a rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model of cerebral ischemia, tPA combined with normobaric hyperoxia reduced tPA-associated mortality, brain edema, hemorrhage, and MMP-9 augmentation compared with tPA alone (Liu et al 2009). While the latter studies commonly focus on mitigating MMP action to limit tPA neurotoxicity and hemorrhage, another approach might be to diminish tPA-associated disruption of the BBB and brain edema. For example, endothelin (ET)-1 binds to the ETA receptor to regulate BBB permeability, is upregulated after stroke, and blockade of ET-1 with an ETA receptor antagonist ameliorates stroke induced brain edema (Matsuo et al 2001). Co-administration of the ETA receptor antagonist S-0139 with tPA reduced infarct volume and improved neurological outcome in a rat embolic MCA occlusion model due to a synergistic effect on improvement of functional outcome as well as a reduction in tPA-associated thrombosis, hemorrhage, and BBB disruption (Zhang et al 2009).

Modulation of tPA signaling by novel PAI-1 inhibitors as an emerging therapeutic strategy for treatment of CNS ischemic disorders

An alternative approach, we have administered novel drugs such as a synthetic hexapeptide derivative of the naturally occurring tPA inhibitor, PAI-1, EEIIMD, which inhibits the vascular activity of tPA and uPA without inhibiting its fibrinolytic activity (Nassar et al 2002; Nassar et al 2004; Armstead et al 2005a). In a model of global cerebral hypoxia/ischemia in newborn pigs, co-administration of EEIIMD with tPA prevented the impairment of hypercapnic and hypotensive pial artery vasodilation (Armstead et al 2005b). In adult rat models of embolic stroke and middle cerebral artery occlusion, EEIIMD decreased infarct volume and hemorrhage while limiting reductions in cerebral blood flow, impaired cerebrovasodilation to activation of the NMDA receptor, and histopathologic changes such as brain edema, neuronal cell necrosis, and hemorrhage after fluid percussion brain injury (Armstead et al 2005a, 2006, 2009a) (Table 1). The beneficial effects of EEIIMD were not due to enhanced tPA clearance or inhibition of tPA’s thrombolytic activity but appeared to be due to its mimicking the action of PAI-1 inhibition of tPA signaling through the LRP receptor (Akkawi et al 2006; Armstead et al 2006). For example, EEIIMD diminishes upregulation of ERK MAPK, contributory to improved cerebral hemodynamics after piglet fluid percussion brain injury (Armstead et al 2009a) (Table 1). Recent initial studies indicate that an 18 amino acid derivative of PAI-1, Ac-RMAPEEIIMDRPFLYVVR-amide, prevents impairment of hypercapnic and hypotensive pial artery dilation by inhibiting JNK MAPK upregulation, when administered either prophylactically (30 min prior to) or therapeutically (2h after) CNS photothrombotic injury in the piglet (Armstead et al 2009d) (Table 1). A key advantage of EEIIMD is the substantial reduction in the risk of hemorrhage in models of CNS ischemia (Armstead et al 2006, 2009a), a significant impediment to the wider use of tPA for treatment of acute ischemic stroke. It has been speculated that if these results can be extended to humans, they could usher in a new era of thrombolytic therapy for stroke (Dawson and Dawson 2006).

Table 1.

Modulation of tPA Signaling and Outcome by PAI-1 Inhibitors in Models of Cerebral Ischemia

| Adult Rat | Newborn Pig | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCAO Embolic Stroke | H/I | FPI | Photothrombosis | |

| tPA Signaling | ⇓ ERK MAPK | ⇓ JNK MAPK | ||

| Outcome | ⇓ Infarct Volume | ⇓ Histopathology, Edema ⇓ Cerebral Hemodynamic Impairment |

||

MCAO = middle cerebral artery occlusion, H/I = hypoxia/ischemia, FPI = fluid percussion injury

Pediatric stroke as an emerging area of tPA therapy and clinical management

Ischemic stroke is also an important, yet understudied, contributor to morbidity and mortality in the pediatric population. The cost of pediatric stroke care is expensive given the lifetime expectancy need for clinical care in this patient population (Perkins et al 2009). Pediatric stroke may occur in as many as 1 in 4000 births (Nelson and Lynch, 2004) and complications due to hypoxia/ischemia are common (Ferriero 2004). Maternal and perinatal coagulopathy predispose to pediatric stroke (Gunther et al 2000; Kraus and Acheen 1999) with 30% of such events being due to thrombosis (DeVeber and Andrew 2001). The use of tPA (Kim et al 1999) in children has been limited and its benefit remains unclear (Benedict et al 2007; Janjua et al 2007). The use of tPA (Cremer et al 2008) in children is based on the assumption that studies in adults are generalizable, but the safety and efficacy of tPA in this setting have yet to be systematically investigated.

A number of considerations should be contemplated when extrapolating the experience with tPA in adults to children, such as dosing, benefit/risk ratio, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic window (Amlie-Lefond and Fullerton 2009). Indeed, the 2001 workshop report of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke noted a deficiency in research in pediatric stroke related to the paucity of animal models and basic research investigation into ischemic disorders of the CNS in the pediatric population (Lynch et al 2002). Many studies of cerebral ischemia have been performed in rodent models. Piglets offer an important advantage in elucidating pathways involved in CNS ischemic injury by virtue of having a gyrencepahalic brain that contains substantial white matter similar to humans, which is more sensitive to ischemic damage than grey matter (Shaver et al 1996). Importantly, the use of a piglet model allows for study of additional physiologic variables and is therefore likely of greater clinical relevance than many rodent models. On the basis of interspecies extrapolation of brain growth curves (Dobbing 1974), the age of the newborn pig used in our studies of the effects of tPA in global cerebral hypoxia/ischemia and fluid percussion brain injury (Armstead et al 2006, 2008) roughly approximated the newborn-infant time period in the human. The identification of a molecular signaling target (ERK MAPK) (Armstead et al 2008) for modifying neuropathologic injury is potentially clinically relevant as there are, to date, no clinically proven neuroprotective interventions other than hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic/ischemic brain injury. Equally important might be the finding that tPA alone can exacerbate neuronal injury in the setting of hypoxia/ischemia (Armstead et al 2005b, 2008). This observation was made in adult models of focal arterial-occlusive stroke years ago, but its significance was diminished, indeed outweighed, by the overwhelming clinical trial evidence of benefit due to fibrinolysis. Yet, the use of tPA for adult acute stroke is highly constrained within a narrow therapeutic window so as to minimize the risk of hemorrhage. Our preliminary extension of investigation of tPA’s benefit/risk ratio in pediatric CNS injury to the more translationally relevant model of piglet photothrombosis (Armstead et al 2009d) is based on the seminal paper establishing this model in the piglet (Kuluz et al 2007). Our studies showing differential roles of ERK and JNK MAPK mechanisms in tPA-associated impairment of cerebral hemodyanamics and histopathology in the setting of pediatric global cerebral hypoxia/ischemia compared to pediatric focal thrombotic injury support our belief that signaling is an emerging issue for optimizing tPA benefit in treatment of CNS ischemic disorders. Equally, these studies emphasize the importance of age, since the effects of tPA and their mediation via signaling systems may vary in pediatric and adult animal models of stroke. Conductance of basic science studies in animal models as a function of age will inform the clinical practice of stroke therapy in the pediatric population.

Coupling tPA to carrier RBC: emerging delivery strategy for cerebral thromboprophylaxis

To be of use in thromboprophylaxis, a fibrinolytic agent should selectively lyse potentially occlusive clots during their formation without affecting hemostatic clots or exerting extravascular toxicity. However, all existing fibrinolytics are short lived (<30 min) and small (<10 nm diameter) agents, capable of diffusion into hemostatic clots. None can be used safely at therapeutic doses in patients with CNS ischemia. Contemporaneous studies from our group have shown that anchoring tPA on red blood cells (RBC) endows the resultant complex, RBC-tPA, with dramatically prolonged circulation time (many hours vs minutes for tPA), while spatially constraining it to the intravascular space with no harmful effects of the carrier RBC (Murciano et al 2003; Ganguly et al 2005; Ganguly et al 2006; Zaitsev et al 2006). RBC-tPA effectively lyses nascent thrombi that otherwise may cause sustained vascular occlusion, but its large size precludes it from entering and lysing preexisting clots and prevents it from extravasation, thereby limiting CNS toxicity. In rodent models of cerebrovascular thrombosis and traumatic brain injury, treatment with this RBC-tPA complex provided effective thromboprophylaxis, rapid reperfusion, neuroprotection, and reduction in mortality all without causing ICH (Danielyan et al 2008; Stein et al, 2009). It is presently uncertain, however, if the value of RBC-tPA for microclots encountered in the latter rodent models can be recapitulated in lysing thrombi of the size encountered in human stroke. Nonetheless, in unrelated studies using a piglet model of cerebral hypoxia/ischemia, RBC-tPA administered either prior to or post onset of the injury prevented impairment of cerebrovasodilation to hypercapnia and hypotension while concomitantly reducing histopathology in the parietal cortex and CA1 hippocampus (Armstead et al 2009b). While certainly some of the therapeutic potency of RBC-tPA in the setting of cerebral hypoxia/ischemia may relate to its long biological half-life, its influence on tPA-mediated signaling is probably of at least equal importance (Armstead et al 2009b). In support of the latter notion, RBC-tPA exerts anti-inflammatory (ERK MAPK inhibition) and neuroprotective effects while free tPA augmented pro-inflammatory signaling by potentiating LRP mediated upregulation of ERK MAPK, which aggravated CNS injury (Armstead et al 2009b). These data indicate that RBC-tPA may exert an additional mechanism of neuroprotection in cerebral hypoxia/ischemia by affecting pathological signaling in the CNS. The precise nature of the non-fibrinolytic protective and the injurious signaling seen with RBC-tPA and tPA respectively are currently not fully understood, but may be explained by differences in accessibility to subsets of tPA receptors and resultant signaling pathways within the vasculature and parenchyma. RBC-tPA may actually shift the MAPK isoform profile such that while parenchymal ERK MAPK is inhibited, other isoforms (p38 and/or JNK) are upregulated and mitigate adverse cerebral hemodynamic and histopathologic outcomes in the setting of cerebral hypoxia/ischemia. These studies suggest that RBC carriage may offer a unique opportunity to increase the benefit risk ratio of tPA within the CNS.

Summary and perspectives for improving tPA benefit/risk ratio in treatment of CNS ischemic disorders

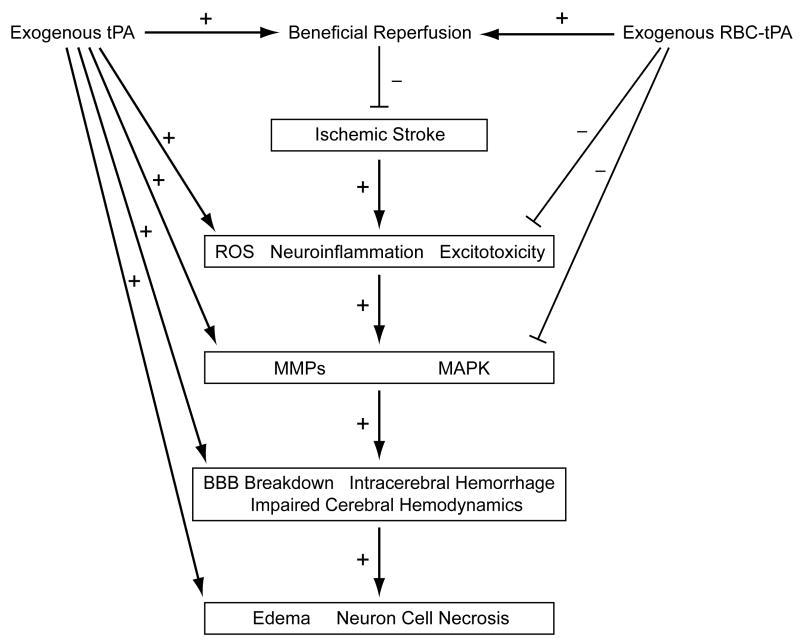

Ischemic stroke is a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality, and tPA remains the only FDA approved treatment for this CNS disorder. Despite its salutary role in reperfusion, tPA also has significant deleterious action including predisposition towards secondary hemorrhage to enhanced excitotoxic neuronal cell death and brain edema (Figure 2). Contemporary approaches towards increasing benefit/risk ratio include use of tPA variants like alteplase to extend the narrow therapeutic window of administration, use of novel neuroprotectants such as the free radical scavenger NXY-059, and co-administration with inhibitors of endothelin like S-0139 and MMP upregulation such as minocycline. A more novel approach to increase benefit/risk for tPA in treatment of CNS ischemic disorders involves the co-administration of PAI-1 derivatives that mimic endogenous PAI-1’s ability to limit tPA signaling. In that context, emerging concepts that are anticipated to have an important influence on this field include tPA signaling, its modulation and its influence on neuronal cell integrity in the context of modifying the biology of the neurovascular unit concept, along with novel delivery systems such as RBC carriage that alter signaling and NVU function. RBC coupled tPA is viewed as a novel approach towards increasing benefit/risk ratio since it retains the positive fibrinolytic aspect of tPA action which restores perfusion while concomitantly mitigating negative aspects of tPA action such as intracerebral hemorrhage, edema, and neuronal cell necrosis via modulation of tPA signaling, such as MAPK (Figure 2). Extension of tPA therapy to treat CNS ischemic disorders in the pediatric population require pre-clinical assessment in pediatric animal models to assess the effect of aging on the response to ischemia and its management. Antagonists of deleterious tPA-mediated signaling and RBC carriage of tPA offer promising opportunities to enhance the efficacy and safety of this thrombolytic in the treatment of CNS ischemic disorders.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram depicting positive promoting (+) or negative opposing (-) actions of exogenous tPA and RBC-tPA in the setting of ischemic stroke.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, NS53410 and HD57355 (WMA), HL76406, CA83121, HL76206, HL07971, and HL81864 (DBC), HL77760 and HL82545 (AARH), HL66442 and HL090697 (VRM), the University of Pennsylvania Research Foundation (WMA and VRM), the University of Pennsylvania Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics (DBC), and the Israeli Science Foundation (AARH).

Footnotes

There are no declared conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkawi S, Nassar T, Tarshis M, et al. LRP and avB3 mediate tPA-activation of smooth muscle cells. AJP. 2006;291:H1351–H1359. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01042.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlie-Lefond C, Fullerton HJ. Thrombolytics for hyperacute stroke in children. Ped Hem Oncology. 2009;26:138–142. doi: 10.1080/08880010902773230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki T, Sumii T, Mori T, et al. Blood brain barrier disruption and matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression during reperfusion injury: mechanical versus embolic focal ischemia in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke. 2002;33:2711–2717. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000033932.34467.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM. Age dependent NMDA contribution to impaired cerebral hemodynamics following brain injury. Develop Brain Res. 2002;139:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00511-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM. NOC/oFQ contributes to age dependent impairment of NMDA induced cerebrovasodilation after brain injury. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:H2188–H2195. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.5.H2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM. Role of endothelin-1 in age dependent cerebrovascular hypotensive responses after brain injury. Am J Physiol. 1999;274:H1884–H1894. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.5.H1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM, Cines DB, Bdeir K, et al. uPA modulates the age dependent effect of brain injury on cerebral hemodyanamics through LRP and ERK MAPK. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009a;29:524–533. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM, Ganguly K, Kiessling JW. Red blood cells-coupled tPA prevents impairment of cerebral vasodilatory responses and tissue injury in pediatric cerebral hypoxia/ischemia through inhibition of ERK MAPK activation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009b;29:1463–1474. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM, Kiessling W, Riley J, et al. tPA contributes to impaired NMDA cerebrovasodilation in newborn pig after traumatic brain injury through activation of JNK MAPK. J Neurotrauma. 2009c;26:A–74. doi: 10.1179/016164110X12807570509853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM, Riley J, Kiessling W, et al. Novel PAI-1 derived peptide protects against impairment of hypercapnic and hypotensive cerebrovasodilation after piglet photothrombosis through inhibition of JNK and preservation of p38 MAPK upregulation. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2009d;21:409–410. [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM, Cines DB, Bdeir K, et al. uPA impairs cerebrovasodilation after hypoxia/ischemia through LRP and ERK MAPK. Brain Res. 2008;1231:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM, Nassar T, Akkawi S, et al. Neutralizing the neurotoxic effects of exogenous and endogenous tPA. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1150–1155. doi: 10.1038/nn1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM, Cines DB, Higazi AAR. Plasminogen activators contribute to age-dependent impairment of NMDA cerebrovasodilation after brain injury. Develop Brain Res. 2005a;156:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM, Cines DB, Higazi AAR. Plasminogen activators contribute to impairment of hypercapnic and hypotensive cerebrovasodilation after cerebral hypoxia/ischemia in the newborn pig. Stroke. 2005b;36:2265–2269. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000181078.74698.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backsai BJ, Xia MQ, Strickland DK, Rebeck GW, Hyman BT. The endocytic receptor protein LRP also mediates neuronal calcium signaling via N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11551–11556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200238297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benetict SL, Ni OK, Schloesser P, White KS, Bale JF. Intra-arterial thrombolysisin a 2-year-old with cardioembolic stroke. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:225–227. doi: 10.1177/0883073807300296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer S, Berliner Y, Warren D, Jones AE. Successful treatment of pediatric stroke with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA): a case report and review of the literature. CJEM. 2008;10:575–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielyan K, Ganguly K, Ding B, Atochin D, Zaitsev S, Murciano JC, Huang PL, Kasner SE, Cines DB, Muzykantov VR. Cerebrovascular thromboprophylaxis by erythrocyte coupled tPA. Circulation. 2008;118:1442–1449. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.750257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Taming the clot buster tPA. Nat Med. 2006;12:993–994. doi: 10.1038/nm0906-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVeber G, Andrew M. Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis in children. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:417–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108093450604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Zoppo GJ, Mabuchi T. Cerebral microvessel responses to focal ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:879–894. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000078322.96027.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbing J. The later growth of the brain and its vulnerability. Pediatrics. 1974;53:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Regulation of the cerebral circulation: role of endothelium and potassium channels. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:53–97. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Monreal M, Lopez-Atalaya JP, Benchenane K, et al. Arginine 260 of the amino-terminal domain of the NR1 subunit is critical for tissue-type plasminogen activator-mediated enhancement of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50850–50856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriero DM. Neonatal brain injury. New Engl J Med. 2004;351:1985–1995. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Bastan B. Treating acute ischemic stroke. Curr Opinion in Drug Discovery and Development. 2008;11:626–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto S, Katsuki H, Ohnishi M, et al. Plasminogen potentiates thrombin cytotoxicity and contributes to pathology of intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:506–515. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly K, Goel MS, Krasik T, Bdeir K, Diamond SL, Cines DB, Muzykantov VR, Murciano JC. Fibrin affinity of erythrocyte-coupled tissue-type plasminogen activators endures hemodynamic forces and enhances fibrinolysis in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;312:1106–1113. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.093450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly K, Krasik T, Medinilla S, Bdeir K, Cines D, Muzykantov V, Murciano JC. Blood clearance and activity of erythrocyte-coupled fibrinolytics. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2005;312:1106–1113. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.075770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther G, Junker R, Strater R, et al. Symptomatic ischemic stroke in full-term neonates. Stroke. 2000;31:2437–2441. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric stroke. The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) J Am Med Assoc. 1995;274:1017–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosomi N, Lucero J, Heo JH, et al. Rapid differential endogenous plasminogen activator expression after acute middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2001;32:1341–1348. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:347–360. doi: 10.1038/nrn1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janjua N, Nasar A, Lynch JK, Qureshi AI. Thrombolysis for ischemic stroke in children. Data from the nationwide inpatient sample. Stroke. 2007;38:1850–1854. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.473983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Zhang RI, Zhang ZG, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging indexes of therapeutic efficacy of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator treatment of rats at 1 and 4 hours after embolic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell CS, et al. Thrombolytic toxicity: blood brain barrier disruption in human ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:338–343. doi: 10.1159/000118379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiessling JW, Cines DB, Higazi AAR, et al. Inhibition of integrin αvβ3 prevents urokinase plasminogen activator-mediated impairment of cerebrovasodilation after cerebral hypoxia/ischemia. Am J Physiol. 2009a;296:H862–H867. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01141.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiessling JW, Muzykantov V, Cines DB, et al. tPA contributes to impaired cerebral hemodynamics after piglet photothrombotic injury through JNK and not ERK MAPK. Stroke. 2009b;40:110. [Google Scholar]

- Kilic E, Hermann DM, Hossmann KA. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator reduces infarct size after reversible thread occlusion of middle cerebral artery in mice. Neuroreport. 1999;10:107–111. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199901180-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, Park JH, Hong SH, Koh JY. Nonproteolytic neuroprotection by human recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. Science. 1999;284:647–50. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5414.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus FT, Acheen VI. Fetal thrombotic vasculopathy in the placenta: cerebral thrombi and infarcts, coagulopathies, and cerebral palsy. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:759–769. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuluz JW, Prado R, He D, Zhao W, Dietrich WD, Watson B. New pediatric model of ischemic stroke in infant piglets by photothrombosis. Stroke. 2007;38:1932–1937. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.475244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laher I, Zhang JH. Protein kinase C and cerebral vasospasm. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:887–906. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansberg MG, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN. Efficacy and safety of tissue plasminogen activator 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:2438–2441. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.552547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapchak PA. Hemorrhagic transformation following ischemic stroke: significance, causes, and relationship to therapy and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2002;2:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11910-002-0051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapchak PA, Araujo DM. Advances in ischemic stroke treatment: neuroprotective and combination therapies. Expert Opin Emerging Drugs. 2007;12:97–112. doi: 10.1517/14728214.12.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapchak PA, Araujo DM. Reducing bleeding complications after thrombolytic therapy for stroke: clinical potential of metalloproteinase inhibitors and spin trap agents. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:819–829. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115110-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SR, Guo SZ, Scannevin RH, et al. Induction of matrix metalloproteinase, cytokines, and chemokines in rat cortical astrocytes exposed to plasminogen activators. Neurosci Lett. 2007;417:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Hendren J, Qin XJ, et al. Normobaric hyperoxia reduces the neurovascular complications associated with delayed tissue plasminogen activator treatment in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2009;40:2526–2531. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.545483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo EH, Broderick JP, Moskowitz MA. tPA and proteolysis in the neurovascular unit. Stroke. 2004;35:354–356. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000115164.80010.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo EH, Dalkara T, Moskowitz MA. Mechanisms, challenges and opportunities in stroke. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:399–415. doi: 10.1038/nrn1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JK, Hirtz DG, DeVeber G, Nelson KB. Report of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke workshop on perinatal and childhood stroke. Pediatrics. 2002;109:116–123. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado LS, Sazonova IY, Kozak A, et al. Minocycline and tissue-type plasminogen activator for stroke. Assessment of interaction potential. Stroke. 2009;40:3028–3033. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.556852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo Y, Mihara S, Ninomiya M, et al. Protective effect of endothelin typa a receptor antagonist on brain edema and injury after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Stroke. 2001;32:2143–2148. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.94259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcor JP, Pawlak R, Strickland S. The tissue plasminogen activator-plasminogen proteolytic cascade amyloid β (Aβ) degradation and inhibits Aβ-induced neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8867–8871. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-26-08867.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng W, Wang X, Asahi M, et al. Effects of tissue type plasminogen activator in embolic versus mechanical models of focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1316–1321. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199912000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meretoja A, Tatlisumak T. Novel thrombolytic drugs. Will they make a difference in the treatment of ischemic stroke? CNS Drugs. 2008;22:619–629. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murciano JC, Medinilla S, Eslin D, Atochina E, Cines DB, Muzykantov VR. Prophylactic fibrinolysis through selective dissolution of nascent clots by tPA-carrying erythrocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:891–896. doi: 10.1038/nbt846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai N, Zhao BQ, Suzuki Y, et al. Tissue-type plasminogen activator has paradoxical roles in focal cerebral ischemic injury by thrombotic middle cerebral artery occlusion with mild or severe photochemical damage in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:648–651. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar T, Akkawi S, Shina A, et al. The in vitro and in vivo effect of tPA and PAI-1 on blood vessel tone. Blood. 2004;103:897–902. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar T, Haj-Yehia A, Akkawi S, et al. Binding of urokinase to low density lipoprotein-related receptor (LRP) regulates vascular smooth muscle cell contraction. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40499–404504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KB, Lynch JK. Stroke in newborn infants. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:150–158. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00679-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicole O, Docagne F, Ali C, Margaill I, et al. The proteolytic activity of tissue plasminogen activator enhances NMDA receptor-mediated signaling. Nature Med. 2001;7:59–64. doi: 10.1038/83358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa K, Younkin L, Ebeling C, et al. Abeta 1-40-related reduction in functional hyperemia in mouse neocortex during somatosensory activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9735–9740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth K, Madison EL, Gething MJ, et al. Complexes of tissue-type plasminogen activator and its serpin inhibitor type 1 are internalized by means of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein/alpha 2-macroglobulin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7422–7426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder T, Contartese J, Stoeckli ET, et al. Neuroserpin, an axonally secreted serine protease inhibitor. EMBO J. 1996;15:2944–2953. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paciaroni M, Medeiros E, Bogousslavsky J. Desmoteplase. Exp Opin Biol Therapy. 2009;9:773–778. doi: 10.1517/14712590902991497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parathath SR, Parathath S, Tsirka SE. Nitric oxide mediates neurodegeneration and breakdown of the blood-brain barrier in tPA-dependent excitotoxic injury in mice. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:339–349. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park L, Gallo EF, Anrather J, et al. Key role of tissue plasminogen activator in neuro-Vascular coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1073–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708823105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak R, Melchor JP, Matys T, et al. Ethanol-withdrawal seizures are controlled by tissue plasminogen activator via modulation of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:443–448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406454102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins E, Stephens J, Xiang H, Lo W. The cost of pediatric stroke acute care in the United States. Stroke. 2009;40:2820–2827. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.548156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polavarapu R, Gongora MC, Ranganthan S, Lawrence DA, Strickland D, Yepes M. Tissue-type plasminogen activator-mediated shedding of astrocytic low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein increases the permeability of the neurovascular unit. Blood. 2007;109:3270–3278. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-043125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver EG, Duhaime AC, Curtis M, Gennarelli LM, Barrett R. Experimental acute subdural hematoma in infant piglets. Pediatric Neurosurgery. 1996;125:123–129. doi: 10.1159/000121109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuaib A, Lees KR, Lyden P, et al. NXY-059 for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:562–571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein SC, Ganguly K, Belfeld CM, et al. Erythrocyte bound tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is neuroprotective in experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1585–1592. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su EJ, Fredriksson L, Geyer M, et al. Activation of PDGF-CC by tissue plasminogen activator impairs blood brain barrier integrity during ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2008;14:731–737. doi: 10.1038/nm1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabrizi P, Wang L, Seeds N, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) deficiency exacerbates cerebrovascular fibrin deposition and brain injury in a murine stroke model: studies in tPA deficient mice and wild-type mice on a matched genetic background. Arterioscler Thromb Vascular Biol. 1999;19:2801–2806. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.11.2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsirka SE, Gualandris A, Amaral DG, et al. Excitotoxin-induced neuronal degeneration and seizure are mediated by tissue plasminogen activator. Nature. 1995;377:340–344. doi: 10.1038/377340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji K, Aoki T, Tejima E, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator promotes matrix metallo-proteinase-9 upregulation afer focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2005;36:1954–1959. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177517.01203.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mourik JA, Lawrence DA, Loskutoff DJ. Purification of an inhibitor of plasminogen activator (antiactivator) synthesized by endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:14914–14921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YF, Tsirka SE, Strickland S, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) increases neuronal damage after focal cerebral ischemia in wild type and tPA-deficient mice. Nat Med. 1998;4:228–231. doi: 10.1038/nm0298-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yepes M, Roussel BD, Ali C, et al. Tissue-type plasminogen activator in the ischemic brain: more than a thrombolytic. Trends in Neurosci. 2009;32:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yepes M, Sandkvist M, Moore EG, et al. Tissue-type plasminogen activator induces opening of the blood brain barrier via the LDL receptor-related protein. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1533–1540. doi: 10.1172/JCI19212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsev S, Danielyan K, Murciano JC, Krasik T, Taylor RP, Pincus S, Jones SM, Cines DB, Muzykantov VR. CR-1-directed targeting of tPA to circulating erythrocytes for prophylactic fibrinolysis. Blood. 2006;108:1895–1902. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-012336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang RL, Zhang C, Zhang L, et al. Synergistic effect of an endothelin type A receptor antagonist, S-0139, with tPA on the neuroprotection after embolic stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:2830–2836. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.515684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]