Abstract

In vivo adhesions between cells and the extracellular matrix play a crucial role in cell differentiation, proliferation, and migration as well as tissue remodeling. Natural three-dimensional (3D) matrices, such as self-assembling matrices and Matrigel, have limitations in terms of their biomechanical properties. Here, we present a simple method to produce an acellular human amniotic matrix (AHAM) with preserved biomechanical properties and a favorable adhesion potential. On the stromal side of the AHAM, human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) attached and extended with bipolar spindle-shaped morphology proliferated to multilayer networks, invaded into the AHAM, and migrated in a straight line. Moreover, αV integrin, paxillin, and fibronectin were observed to colocalize after 24 h of HFF culture on the stromal side of the AHAM. Our results indicate that the AHAM may be an ideal candidate as a cell-matrix adhesion substrate to study cell adhesion and invasion as well as other functions in vitro under a tensile force that mimics the in vivo environment.

1. Introduction

Initial studies have revealed that cell-matrix adhesions play a crucial role in cell morphology, migration, differentiation, and proliferation as well as tissue organization and matrix remodeling, all of which are essential for embryonic development and the remodeling and homeostasis of adult tissues [1–4]. Natural three-dimensional (3D) matrices have been adopted as physiological models to analyze cell-matrix interactions, rather than using traditional two-dimensional (2D) tissue culture [5–8].

Cell adhesion to a 3D matrix is referred to as in vivo native cell-matrix adhesion, which differs from focal and fibrillar adhesions [2, 9]. Due to the difficulty of mimicking the 3D aspects of the matrix in vivo, 3D adhesion has been modeled in vitro using in self-assembling matrices and Matrigel [2, 5]. The study of cells attached to a matrix by 3D adhesion is required to design or reproduce physiologically relevant conditions to decipher biological mechanisms, assay drug responses in vitro, and transplant cells in a native physiological state into the body [10].

Self-assembling matrices, Matrigel, and hydrogels are complex, costly to produce, and have limitations in terms of their geometric and biomechanical properties [11]. Thus, development of a tissue-derived matrix in vitro with favorable adhesion potential and biomechanical properties is anticipated. Great efforts have been made to decellularize a variety of tissues including heart valves, blood vessels, skin, nerves, skeletal muscle, tendons, ligaments, small intestinal submucosa, urinary bladder, and liver, [12–18]. However, it has been demonstrated that decellularization can alter the native 3D architecture of the extracellular matrix (ECM).

The human amniotic membrane (HAM) has many characteristics that are desirable for a biomaterial. It is inherently tough, yet devoid of blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves. Additionally, the HAM is nutritionally permeable, inexpensive, easily obtained, and readily available [19, 20]. Currently, decellularization of the HAM is focused on the removal of all cells on the epithelial side, and thus far no study has explored the cell-matrix adhesion potential of its stromal side. In this study, we introduce a method to thoroughly remove cells from both epithelial and stromal sides of the HAM, while preserving the favorable adhesion potential and biomechanical properties. Several types of cells seeded on the stromal side of the acellular human amniotic matrix (AHAM) exhibited bipolar spindle-shaped morphology and migrated in a straight line. Moreover, αV integrin, paxillin, and fibronectin were observed to colocalize on the stromal side of the AHAM at 24 h after seeding human foreskins fibroblasts (HFFs). Our results indicate that the AHAM is a promising potential candidate as a cell-matrix adhesion substrate to study cell adhesion and invasion as well as other functions in vitro under a tensile force that mimics the in vivo environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the AHAM

The study was approved by the General Hospital of Tianjin Medical University Ethical Committee for the usage of biological material for research purposes. All materials were used in compliance with ethical guidelines. Fresh HAM was obtained after caesarian deliveries. Maternal donors provided informed consent and were serologically negative for HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis. Briefly, blood clots were immediately cleaned off the placenta after surgery with sterile Ringer's solution containing antibiotics. The HAM was peeled from the chorion and rinsed extensively in Ringer's solution. Then, the HAM was cut into 10 × 10 cm2 pieces and fixed to a stainless-steel ring supported by a tripod. The HAM was then submerged in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 2% trypsin (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and 0.05 mg/mL EDTA (Sigma Aldrich) and incubated at 37°C. A magnetic stirring bar (C350-21, BOLA) just beneath the HAM was used to stir the mixture at 100 rpm/min for the epithelial side for 20 min, and then another 20 min for the stromal side. After washing away debris with PBS, the AHAM was preserved in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) (Gibco BRL) containing antibiotics. The preparation procedures were carried out under aseptic conditions, and no particular sterilization process was performed.

2.2. Assessment of Biomechanical Properties

All samples were tested under a uniaxial tensile low-strain rate and loading to failure using an electronic universal testing machine (CSS-44001; Changchun Research Institute for Testing Machines, China) according to the method by Wilshaw et al. [21]. Twelve paired samples of fresh HAM and AHAM were used. Before mounting the tissue strips (15 × 40 mm) on the holder, the thickness was measured at six points using a Mitutoyo thickness gauge with a resolution of 0.01 mm, and the average thickness was recorded. Strips were then clamped onto the holder with a gauge length of 15 mm. Zero extension was set at the point with a preload of 0.01 N. For each measurement, failure had to occur in the center of the sample, or the test was discarded. Data were interpreted using the software designed for the testing rig and further analyzed using SPSS 11.5 (IBM, USA).

2.3. Cell Culture

HFFs were obtained from samples of healthy boys (12–14-year old) during circumcisions after receiving informed consent from the individual's guardian in compliance with ethical guidelines. After subcutaneous tissue removal, dermal specimens were fragmented with scissors into 5 mm2 pieces. Samples were then rinsed eight times with PBS and vigorous agitation. These fragments were placed into Petri dishes and cultured in DMEM containing 20% (w/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco BRL), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Bone marrow was aspirated from four calf tibia bones in compliance with ethical guidelines. Cells were flushed out from the bone marrow with DMEM containing 50 U/mL penicillin, 0.05 mg/mL streptomycin, and 0.2 mM L-glutamine, collected, and centrifuged at 1509 g for 10 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in complete medium consisting of Minimum Essential Medium alpha supplemented with 15% FBS, 50 U/mL penicillin, and 0.05 mg/mL streptomycin, and then plated in T75 flasks. After 48 h of culture, nonadherent cells were removed, and fresh medium was added to the cells. At subconfluence, cells were harvested by trypsinization and replated at a 1 : 3 split ratio. Cells were cultured for no more than four passages. NIH 3T3 cells (ATCC Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM containing 10% bovine calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. All reagents used for cell culture were purchased from Gibco BRL-Life Technologies.

2.4. Histology and Immunohistochemistry

HAM and AHAM specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h, rinsed with PBS, and stored in 70% alcohol. After dehydration in an ascending ethanol series, HAM specimens were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 3-4 mm on a rotary microtome, deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in a descending alcohol series, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Five micrometer sections of paraffin-embedded AHAM were stained with primary polyclonal antibodies against human collagen I (SAB4500363; Sigma Aldrich), collagen II (SAB4500366; Sigma Aldrich), collagen III (SAB4500367; Sigma Aldrich), collagen IV (SAB4500375; Sigma Aldrich), laminin (L9393; Sigma Aldrich), TGF-β1 (SAB4502958, Sigma Aldrich) and TGF-β2 (SAB4502960, Sigma Aldrich), and a monoclonal antibody against fibronectin (F0916; Sigma Aldrich) according to the manufacturers' procedures and routine immunohistochemistry methods.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed according to the following procedures. Specimens were fixed overnight in 4% (w/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate, washed three times for 15 min in 0.1 M cacodylate, and postfixed for 1 h in 1% (w/v) aqueous osmium tetraoxide. Then, specimens were washed three times in distilled water, dehydrated through a graded acetone series (30, 50, 70, 80, 90, 95, 100%, acetone mixture and in pure acetone), dried to the critical point in a drier (Bal Tec, CPD 030) with CO2 and finally mounted on an aluminum stub and sputtercoated with gold before examination by SEM (S-3500N, Hitachi, Japan).

2.5. Quantification of Cell Morphology

At 24 h after seeding HFFs on glass coverslips or the AHAM, β-actin was detected to visualize the cytoskeleton and morphology by immunofluorescence staining using a primary polyclonal antibody (sc-130656; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) according to manufacturers' procedure. The cell axial ratio (cell length/width) and total cell spread area of HFFs were digitally determined as described elsewhere [5, 22].

2.6. Immunofluorescence Staining and Confocal Microscopy

Three types of matrices for cell culture were used, namely the AHAM, Matrigel, and glass coverslips. Glass coverslips were coated with either the AHAM or 0.2 mL Matrigel (5 mg/mL) in a 24-well plate (Carolina Biological Supply Co.). The Matrigel layer was 10 μm. Cells were cultured overnight on the stromal side of the AHAM, Matrigel or glass coverslips in DMEM containing 10% (w/v) FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

All subsequent steps were performed at room temperature. Briefly, cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed for 5 min with 2% (w/v) formaldehyde in PBS, rinsed three times with 0.5% (w/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, and then incubated with polyclonal antibodies against αV integrin (sc-6595; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and paxillin (sc-5574; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and a monoclonal antibody against fibronectin (sc-69681; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at 37°C. After rinsing three times with 0.5% (w/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, cells were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to AMCA/TRITC/FITC (50 μg/mL; Jackson ImmunoResearch) in PBS for 1 h and then washed three times with 0.5% (w/v) Triton X-100 in PBS for at least 30 min. Stained samples were mounted in GEL/MOUNT (Biomeda Corp) containing 1 mg/mL 1,-4-phenylenediamine (Fluka) to reduce photobleaching. Immunofluorescence images were obtained with a Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (TCS-SP5, Leica, Germany).

2.7. Time-Lapse Analysis

HFF migration patterns were observed at 8 h after seeding on glass coverslips or the AHAM. Time-lapse images of cell movements were recorded every 15 min over 6 h with a CCD camera (Nikon, DXM1200C) attached to an inverted microscope (Nikon, TS100) with a 10× objective lens, which was fitted with a 37°C/5% CO2 incubator stage consisting of an enclosed chamber with temperature and CO2 controls. Image stacks were converted using the ImageJ plug-in for smart projector (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/plugins/smart-projector/index.html). Nuclei were tracked to quantify cell motility, and the velocities were calculated in micrometers every 15 min using the ImageJ plug-in (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/plugins/track/track.html).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All numerical data were presented as the means ± standard deviation. Statistically significant differences between two groups were calculated using the 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Results

3.1. Histology of the AHAM

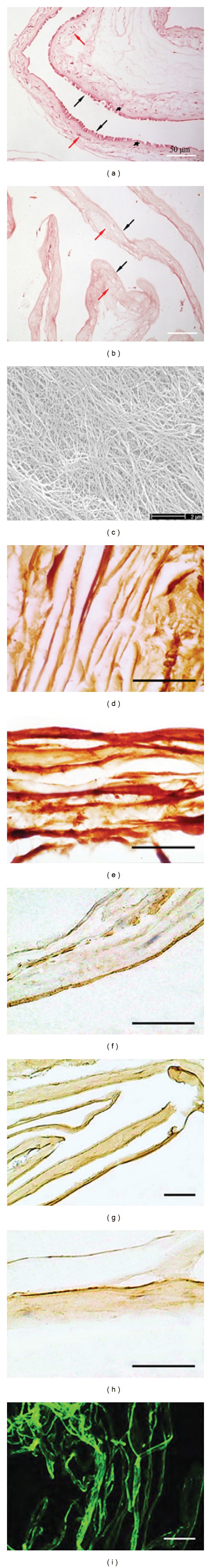

The HAM was composed of five layers: the amniotic epithelium, basement membrane, compact connective tissue, fibroblast layer, and spongy layer (Figure 1(a)). The epithelial layer and fibroblasts in the stromal side were thoroughly removed for the AHAM that was negative for hematoxylin staining (Figure 1(b)). Under SEM, the stromal layer of the AHAM was composed of a reticular structure with long collagen fibers of various diameters, without interruption or breaks (Figure 1(c)). Many pits and niches (approximately 10 μm in diameter) were observed on the rugged stromal surface. Additional fragments were not found on the bare long collagen fibers, indicating no residual cell debris (Figure 1(c)).

Figure 1.

Histology of the HAM and AHAM. (a) The HAM was composed of five layers as shown by HE staining. Black arrows indicate the epithelial layer, asterisk indicates the basement membrane, and red arrows indicate the avascular stroma layer. (b) The epithelial layer and fibroblasts in the stromal side were thoroughly removed for the AHAM. Black and red arrows indicate the basement membrane and stromal layer, respectively. Scale bar, 50 μm. (c) SEM image of the AHAM. The stromal layer was reticular and composed of collagen fibers with various diameters. There was no residual cell debris. Scale bar, 2 μm. (d) Type I collagen, (e) type III collagen, (f) type IV collagen, (g) fibronectin, and (h) laminin were positive in immunohistochemistry staining. (i) Type VI collagen was positive in immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar, 50 μm.

The AHAM was positive for type I, III, IV, and VI collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, as shown by immunohistochemical or immunofluorescence staining (Figures 1(d)–1(i)). Type II collagen, TGF-β1, and TGF-β2 were not observed in the AHAM (data not shown).

3.2. Biomechanics of the AHAM

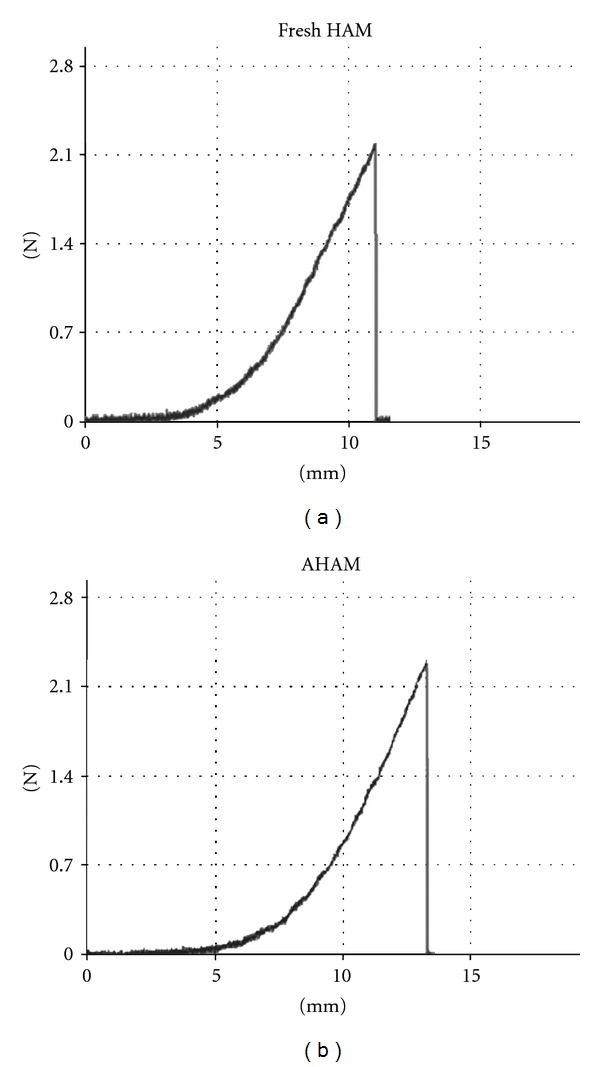

Results of the biomechanical testing are summarized in Table 1. Although the AHAM was slighter thinner than the fresh control (0.143 ± 0.005 mm versus 0.164 ± 0.006 mm), the AHAM showed no significant differences in transition strain and stress or failure strain, compared with those of fresh samples (Figure 2). The process of decellularization did not compromise the strength of the resulting matrix, as shown by the failure stress/ultimate tensile strength at 0.796 ± 0.045 Mpa.

Table 1.

Biomechanical properties of the fresh amnion and the AHAM.

| Parameter | Fresh HAM | AHAM | t value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (n) | 12 | 12 | — | — |

| Thickness (mm) | 0.164 ± 0.006 | 0.143 ± 0.005 | t = 9.42 | P = 0.00 |

| Transitional stress (MPa) | 0.144 ± 0.037 | 0.142 ± 0.026 | t = −1.83 | P = 0.08 |

| Transitional strain (%) | 11.808 ± 0.833 | 12.200 ± 0.959 | t = −1.07 | P = 0.30 |

| Failure strain (MPa) | 0.820 ± 0.028 | 0.796 ± 0.045 | t = 1.57 | P = 0.13 |

| Failure strain (%) | 32.695 ± 1.560 | 33.777 ± 1.359 | t = −1.81 | P = 0.08 |

Figure 2.

Biomechanics of the AHAM. (a) Fresh HAM and (b) AHAM samples were tested under a uniaxial tensile low strain and loading to failure using an electronic universal testing machine. No differences between fresh HAM and AHAM were observed in the stress-strain curve.

3.3. Morphology of Various Cell Types on the AHAM

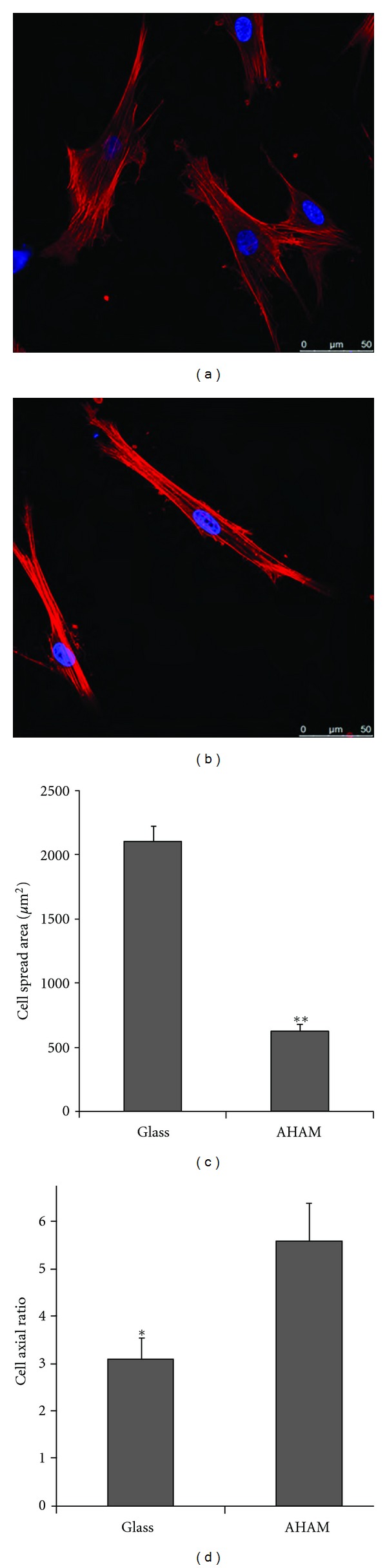

Cell outlines of HFFs on glass coverslips and the AHAM were determined by immunofluorescence staining to visualize the cytoskeleton. HFFs were cultured on glass coverslips or the AHAM for 24 h and then fixed and stained to visualize morphology (Figure 3(a)). Cells cultured on glass coverslips were broader and more flattened, and had more cell protrusions and lamellae than those of cells cultured on the AHAM. Conversely, HFFs cultured on the AHAM showed a more slender appearance with fewer protrusions than those of cells culture on glass coverslips. The length, width, and total area of HFFs were calculated using MetaMorph software. Consistent with the observed differences in cell morphology, the quantitative differences in the cell axial ratio and total cell spread area of HFFs were digitally calculated using 30–50 cells that were representative of each sample by MetaMorph software (Figures 3(b) and 3(c)). The cell axial ratio was 3.3 ± 0.35 for cells cultured on glass coverslips, and 6.3 ± 0.32 for those on the AHAM.

Figure 3.

Morphology of HFFs and quantification of cell length, width, and spread area on the indicated substrates. ((a) and (b)) β-actin was detected by immunofluorescence staining to visualize the cytoskeleton and morphology at 24 h after plating cells on glass coverslips (a) or the AHAM (b). Scale bar, 50 μm. ((c) and (d)) The cell spread area (c) and axial ratio (d) were calculated on the indicated substrates after immunofluorescence staining. Cells on coverslips were nearly twice as large in terms of their cell spread area, compared with that of cells cultured on the AHAM. Error bars indicate standard error (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001).

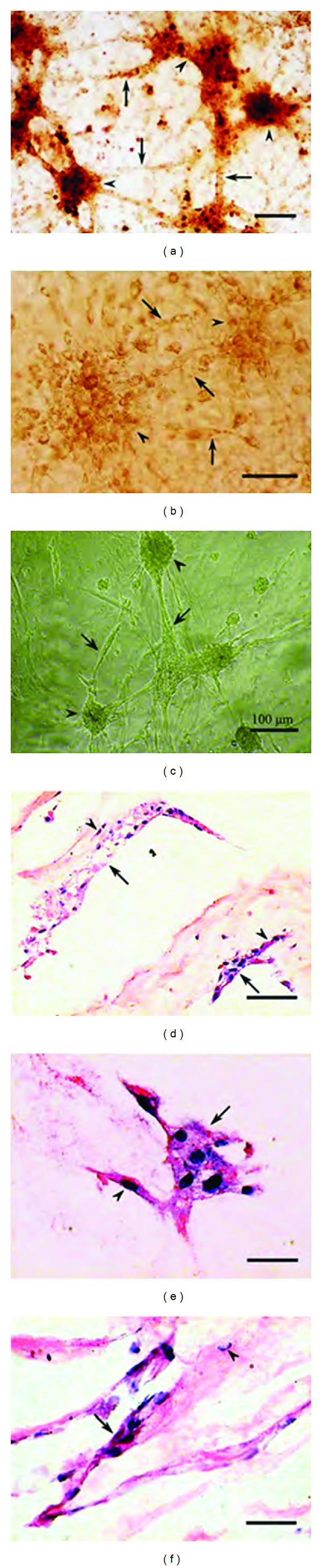

Bovine bone marrow stromal cells and NIH 3T3 cells were also seeded onto the AHAM and showed the same bipolar spindle-shaped morphology. After 96 h of culture on the AHAM, the indicated cells proliferated and formed colonies of star-shaped cell clusters. Moreover, cell colonies connected with each other to form a network after 7 days of culture on the AHAM (Figures 4(a)–4(c)). On the bottom of colonies, cells were observed to invade into the AHAM (Figures 4(d)–4(f)) by HE staining.

Figure 4.

((a)–(c)) Cell colony formation on the AHAM for different cell types. (a) Bovine bone marrow stromal cells, (b) NIH 3T3 cells, and (c) HFFs were observed to form colonies as star-shaped cell clusters. Arrowheads indicate cell clusters, and arrows indicate extensions from the cell clusters. Scale bar, 100 μm. ((d)–(f)) Cells were observed to invade into the AHAM, as indicated by HE staining after 14 days of culture. (d) Bovine bone marrow stromal cells, (e) NIH 3T3 cells, and (f) HFFs. Arrows indicate cell clusters, and arrowheads indicate cells that are nearly penetrating the AHAM. Scale bar, 25 μm.

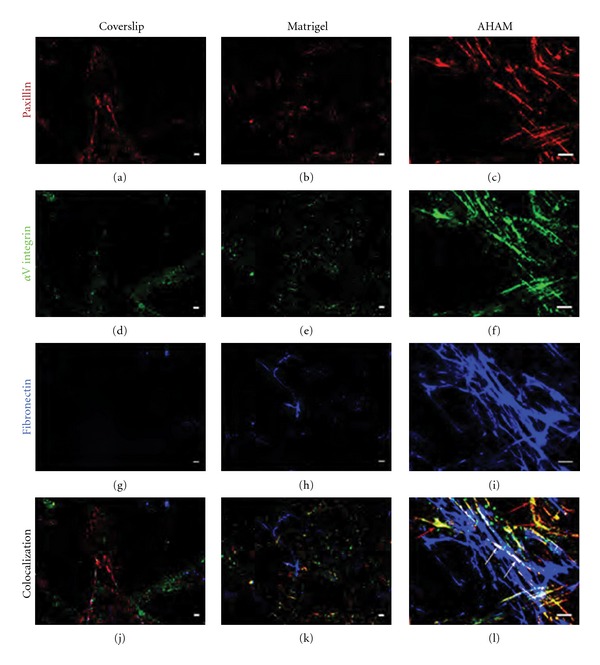

3.4. αV Integrin, Paxillin, and Fibronectin Colocalize to Form a Cell-Matrix Adhesion Complex on the Stromal Side of the AHAM

To compare the cell adhesion structures formed by HFFs adhering to each of the surfaces, αV integrin, paxillin, and fibronectin were detected by immunofluorescence after at least 24 h of HFF culture on the stromal side of the AHAM, Matrigel or coverslips. The expression of αV integrin (Figures 5(a)–5(c)), paxillin (Figures 5(d)–5(f)), and fibronectin (Figures 5(g)–5(i)) was observed in the cell-matrix adhesions in all three surfaces. Triple labeling of αV integrin (green), paxillin (red), and fibronectin (blue) was performed. On the AHAM, colocalized αV integrin, paxillin, and fibronectin, appearing as white bands, were detected (Figure 5(l)) by immunofluorescence, indicating that these proteins formed a cell-matrix adhesion complex. Colocalization of αV integrin and paxillin was also detected (Figure 5(l)) without fibronectin. Conversely, no colocalization of these proteins was visualized with cell adhesions to Matrigel or coverslips (Figures 5(j) and 5(k)).

Figure 5.

Confocal images of indirect immunofluorescence staining of HFFs on the AHAM, glass coverslips, and Matrigel. Triple labeling of αV integrin (green) ((a)–(c)), paxillin (red) ((d)–(f)), and fibronectin (blue) ((g)–(i)) was performed. Colocalization was observed as white bands (white arrows) only within the AHAM (l), and not with cell adhesions on coverslips (j) or Matrigel (k). Colocalization of αV integrin and paxillin was detected as yellow bands (red arrows) in regions without fibronectin only within the AHAM (l). Scale bar, 10 μm.

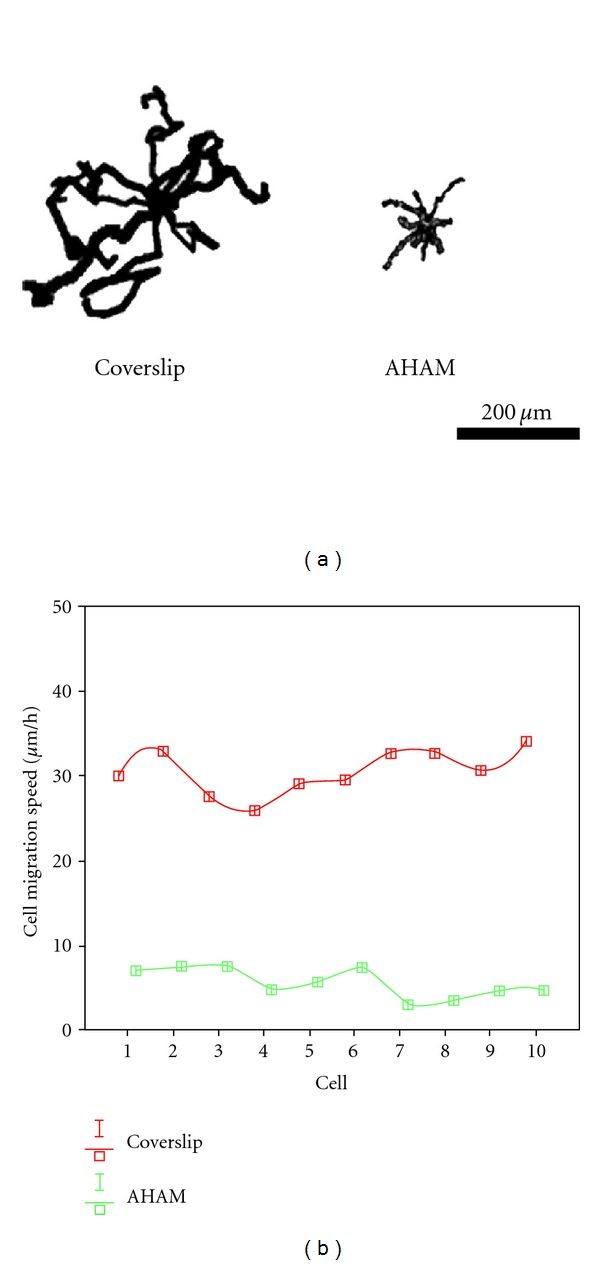

3.5. Mode of Cell Migration on the AHAM

At 8 h after seeding HFFs on coverslips or the AHAM, cell migration was recorded. On the AHAM, HFFs moved with more monoleading processes in an almost straight line, whereas cells migrated on coverslips in a random direction (Figure 6(a)). Cells migrated much faster on coverslips than on the AHAM. Results showed that cells migrated at an average speed of 5 μm/h on the AHAM, whereas the average speed was about 30 μm/h on coverslips (Figure 6(b)). When cells formed clusters in situ on the AHAM, migration was not observed.

Figure 6.

HFF migration patterns at 8 h after seeding. Images were obtained every 15 min over a 6 h period. (a) Ten representative paths of cells on coverslips or the AHAM were positioned with a common origin to generate a star-like pattern. Faster migration produced larger star patterns. On the AHAM, HFFs moved with more monoleading processes in an almost straight line, whereas HFFs on coverslips moved randomly. (b) Chart showing that the speed was significantly different between cells cultured on the AHAM and coverslips. Scale bar, 200 μm.

4. Discussion

The development of optimal biocompatible scaffolds for tissue engineering requires a deep understanding of the interactions between cells and the ECM in vivo. Natural 3D matrices have been adopted as physiological models to analyze cell-matrix interactions, rather than traditional 2D tissue culture. We have developed a new simple method using 2% trypsin and 0.05 mg/mL EDTA to decellularize fresh HAM, in which cells and debris on both stromal and epithelial sides are thoroughly removed, while the favorable cell-matrix adhesion potential and biomechanical properties are preserved.

Various attempts have been made to modify the HAM, including chemical and physical cross-linking [23], to enhance its physical properties and remove all cellular components from the HAM in an attempt to produce a biological substrate for seeding various cell types [24–28]. Recently, cells have been removed from the stromal side of the HAM by SDS. However, SDS tends to disrupt the native tissue structure and causes a loss of collagen integrity [29]. Alternatively, trypsin/EDTA does not affect the amount of collagen in tissues [30]. Moreover, in our study, no denaturing of the collagen was observed on the stromal side of the AHAM by SEM, and type I, III, IV and VI, collagens were detected by immunohistochemistry in the AHAM treated by our method. It has been reported that prolonged exposure to trypsin/EDTA greatly decreases the amount of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). Because tensile strength is closely related to the amount of GAGs, the loss of GAGs contributes to a decrease of tensile strength [31, 32]. In the present study, the AHAM showed no differences in transition strain and stress, or failure strain, compared with those at predigestion, suggesting that the loss of GAGs may be negligible.

Trypsin substantially reduces the laminin and fibronectin content of the ECM [30]. On the surface of the AHAM before seeding HFFs, both fibronectin and laminin were not observed by immunofluorescence (data not shown). Surprisingly, at 40 min after seeding HFFs, the cells attached and fibronectin were detected by immunofluorescence. It is likely that HFFs self-assembled fibronectin on the collagen surface of the AHAM. The appearance of self-assembled fibronectin was not observed in the control group. In fact, fibronectin has not been detected in any of the current fabricated matrices [33].

HFFs in the AHAM tended to show a more spindle-shaped morphology, fewer branched terminal processes, or fewer protrusions and lamellipodia, as well as a smaller total cell spread area than those of cells cultured on a glass substrate. The cell axial ratio of HFFs cultured on the AHAM was quite similar, whereas HFFs cultured on glass coverslips had a flattened morphology. The shape of cells cultured on the AHAM resembles that of fibroblasts and mesenchymal cells in vivo [5, 34, 35].

Cells plated on the AHAM showed colocalization of αV integrin, paxillin, and fibronectin. Even in regions of the AHAM without fibronectin, colocalization of both αV integrin and paxillin was observed. Paxillin combines with various integrins to recruit regulatory and structural proteins that control the dynamic changes of cell adhesion, cytoskeletal reorganization, and gene expression that are necessary for cell migration and survival [36, 37]. Cultured NIH 3T3 cells have been removed from dishes to produce a self-assembled matrix that, together with Matrigel, shows the features of 3D adhesion in vitro [2, 5]. However, such as self-assembled matrix and Matrigel are hydrogels. Moreover, the self-assembled matrix is relatively thin at only 8 μm, which limits the biomechanical properties to study cells of interest in culture under tensile strength. In our study, the AHAM maintained its biomechanical properties, and various cell types, including bone marrow stromal cells, HFFs, and NIH 3T3 cells, were verified to proliferate and invade the AHAM.

For many cell types, such as fibroblasts and macrophages, it is important to migrate through the ECM to carry out functions such as tissue repair and remodeling. We compared the cell migration of HFFs cultured on the AHAM and glass coverslips. HFFs migrated on the AHAM with mono-leading processes in a straight line at an average speed of 5 μm/h, which is different from the migration speed on self-assembling matrices [5]. On coverslips, cell migration was multidirectional, and the speed was similar to that observed in previous studies [38]. This observation demonstrated the validity of our cell migration protocol. It should be noted that the speed and direction of adherent cell migration in vivo has not yet been defined. Thus, there is no standard to evaluate cell migration with 3D adhesion. It is clear that the biomechanical environment is crucial for cell migration, thus our production of an AHAM will be an alternative matrix on which to study cell migration with 3D adhesion in vitro.

We removed endogenous fibroblasts from the AHAM that lost the properties of anti-inflammation and inhibition of regeneration. This finding could lead to an alternative use of the AHAM as a matrix for bridging regeneration or loading cells for transplantation into the body. Complexes of αV integrin, paxillin and fibronectin, a bipolar cell shape, and multilayer cell clusters, which are characteristics of cells in vivo [39–41], were verified for HFFs cultured on the stromal side of the AHAM. In summary, we have developed a rapid cost-effective method to produce AHAMs with a favorable adhesion potential, while preserving the biomechanical properties. Thus, our AHAM could be a an ideal candidate as a cell-matrix adhesion substrate to study cell adhesion and invasion as well as other functions in vitro under a tensile force that mimics the in vivo environment.

Authors' Contribution

Q. Guo and X. Lu contributed equally to this work.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30772193, 30571876, and 30973024), the Tianjin Key Project Plan in Science and Technology (07JCZDJC08000), and Science Foundation of Tianjin Medical University (2011KY01).

References

- 1.Martino MM, Mochizuki M, Rothenfluh DA, Rempel SA, Hubbell JA, Barker TH. Controlling integrin specificity and stem cell differentiation in 2D and 3D environments through regulation of fibronectin domain stability. Biomaterials. 2009;30(6):1089–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harunaga JS, Yamada KM. Cell-matrix adhesions in 3D. Matrix Biology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Worth DC, Hodivala-Dilke K, Robinson SD, et al. αvβ3 integrin spatially regulates VASP and RIAM to control adhesion dynamics and migration. Journal of Cell Biology. 2010;189(2):369–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang CF, Lee MW, Kuo PY, Wang YJ, Tu YH, Hung SC. Three-dimensional collagen fiber remodeling by mesenchymal stem cells requires the integrin-matrix interaction. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research A. 2007;80(2):466–474. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294(5547):1708–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun T, Jackson S, Haycock JW, MacNeil S. Culture of skin cells in 3D rather than 2D improves their ability to survive exposure to cytotoxic agents. Journal of Biotechnology. 2006;122(3):372–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada KM, Cukierman E. Modeling tissue morphogenesis and cancer in 3D. Cell. 2007;130(4):601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rangarajan R, Zaman MH. Modeling cell migration in 3D: status and challenges. Cell Adhesion & Migration. 2008;2(2):106–109. doi: 10.4161/cam.2.2.6211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Cell interactions with three-dimensional matrices. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2002;14(5):633–639. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rnjak J, Li Z, Maitz PKM, Wise SG, Weiss AS. Primary human dermal fibroblast interactions with open weave three-dimensional scaffolds prepared from synthetic human elastin. Biomaterials. 2009;30(32):6469–6477. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Annabi N, Mithieux SM, Boughton EA, Ruys AJ, Weiss AS, Dehghani F. Synthesis of highly porous crosslinked elastin hydrogels and their interaction with fibroblasts in vitro. Biomaterials. 2009;30(27):4550–4557. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appleton AJE, Appleton CTG, Boughner DR, Rogers KA. Vascular smooth muscle cells as a valvular interstitial cell surrogate in heart valve tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering A. 2009;15(12):3889–3897. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koizumi N, Inatomi T, Quantock AJ, Fullwood NJ, Dota A, Kinoshita S. Amniotic membrane as a substrate for cultivating limbal corneal epithelial cells for autologous transplantation in rabbits. Cornea. 2000;19(1):65–71. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang D, Guo T, Nie C, Morris SF. Tissue-engineered blood vessel graft produced by self-derived cells and allogenic acellular matrix: a functional performance and histologic study. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2009;62(3):297–303. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318197eb19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tudorache I, Cebotari S, Sturz G, et al. Tissue engineering of heart valves: biomechanical and morphological properties of decellularized heart valves. Journal of Heart Valve Disease. 2007;16(5):567–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ponce Márquez S, Martínez VS, McIntosh Ambrose W, et al. Decellularization of bovine corneas for tissue engineering applications. Acta Biomaterialia. 2009;5(6):1839–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng HW, Tsui YK, Cheung KMC, Chan D, Chan BP. Decellularization of chondrocyte-encapsulated collagen microspheres: a three-dimensional model to study the effects of acellular matrix on stem cell fate. Tissue Engineering C. 2009;15(4):697–706. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2008.0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang D, Guo T, Nie C, Morris SF. Tissue-engineered blood vessel graft produced by self-derived cells and allogenic acellular matrix: a functional performance and histologic study. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2009;62(3):297–303. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318197eb19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arora R, Mehta D, Jain V. Amniotic membrane transplantation in acute chemical burns. Eye. 2005;19(3):273–278. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahman I, Said DG, Maharajan VS, Dua HS. Amniotic membrane in ophthalmology: indications and limitations. Eye. 2009;23(10):1954–1961. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilshaw SP, Kearney JN, Fisher J, Ingham E. Production of an acellular amniotic membrane matrix for use in tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering. 2006;12(8):2117–2129. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hakkinen KM, Harunaga JS, Doyle AD, Yamada KM. Direct comparisons of the morphology, migration, cell adhesions, and actin cytoskeleton of fibroblasts in four different three-dimensional extracellular matrices. Tissue Engineering A. 2011;17(5-6):713–724. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujisato T, Tomihata K, Tabata Y, Iwamoto Y, Burczak K, Ikada Y. Cross-linking of amniotic membranes. Journal of Biomaterials Science. 1999;10(11):1171–1181. doi: 10.1163/156856299x00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He Q, Chen B, Wang Z, Li Q. The experimental study of culture in vitro of fibroblasts seeded onto human amnion extracellular matrix (HA-ECM) Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai ke Za Zhi. 2002;18(4):229–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He Q, Li Q, Chen B, Wang Z. Repair of flexor tendon defects of rabbit with tissue engineering method. Chinese Journal of Traumatology. 2002;5(4):200–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinoshita S, Nakamura T. Development of cultivated mucosal epithelial sheet transplantation for ocular surface reconstruction. Artificial Organs. 2004;28(1):22–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2004.07319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo JC, Li XQ, Yang ZM. Preparation of human acellular amniotic membrane and its cytocompatibility and biocompatibility. Zhongguo Xiu fu Chong Jian wai ke za Zhi. 2004;18(2):108–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mligiliche N, Endo K, Okamoto K, Fujimoto E, Ide C. Extracellular matrix of human amnion manufactured into tubes as conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2002;63(5):591–600. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shortt AJ, Secker GA, Lomas RJ, et al. The effect of amniotic membrane preparation method on its ability to serve as a substrate for the ex-vivo expansion of limbal epithelial cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30(6):1056–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbert TW, Sellaro TL, Badylak SF. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials. 2006;27(19):3675–3683. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du Y, Chia SM, Han R, Chang S, Tang H, Yu H. 3D hepatocyte monolayer on hybrid RGD/galactose substratum. Biomaterials. 2006;27(33):5669–5680. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Connelly JT, García AJ, Levenston ME. Inhibition of in vitro chondrogenesis in RGD-modified three-dimensional alginate gels. Biomaterials. 2007;28(6):1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lei P, Padmashali RM, Andreadis ST. Cell-controlled and spatially arrayed gene delivery from fibrin hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2009;30(22):3790–3799. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedl P, Bröcker EB. The biology of cell locomotion within three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2000;57(1):41–64. doi: 10.1007/s000180050498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beningo KA, Dembo M, Wang YL. Responses of fibroblasts to anchorage of dorsal extracellular matrix receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(52):18024–18029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405747102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bukahrova T, Weijer G, Bosgraaf L, Dormann D, van Haastert PJ, Weijer CJ. Paxillin is required for cell-substrate adhesion, cell sorting and slug migration during Dictyostelium development. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118(18):4295–4310. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crowe DL, Ohannessian A. Recruitment of focal adhesion kinase and paxillin to β1 integrin promotes cancer cell migration via mitogen activated protein kinase activation. BMC Cancer. 2004;4:p. 18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dahlmann-Noor AH, Martin-Martin B, Eastwood M, Khaw PT, Bailly M. Dynamic protrusive cell behaviour generates force and drives early matrix contraction by fibroblasts. Experimental Cell Research. 2007;313(20):4158–4169. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kreger ST, Voytik-Harbin SL. Hyaluronan concentration within a 3D collagen matrix modulates matrix viscoelasticity, but not fibroblast response. Matrix Biology. 2009;28(6):336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsusaki M, Yoshida H, Akashi M. The construction of 3D-engineered tissues composed of cells and extracellular matrices by hydrogel template approach. Biomaterials. 2007;28(17):2729–2737. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin SP, Kyriakides TR, Chen JJJ. On-line observation of cell growth in a three-dimensional matrix on surface-modified microelectrode arrays. Biomaterials. 2009;30(17):3110–3117. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]