Abstract

Objective

To determine the effectiveness of rituximab therapy for patients with granulomatous disease of the eye.

Methods

Retrospective review was undertaken of cases seen at a single institution for ocular antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis or sarcoidosis with persistent ocular disease despite systemic therapy. All patients were treated with rituximab and followed for at least 6 months.

Results

Nine patients were identified (five with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis, four with sarcoidosis), and all were treated for at least 6 months. Eight experienced improvement of eye disease and were able to reduce prednisone and other drug therapies. One patient remained stable, but still required high dosages of prednisone. All five patients with lung disease improved with rituximab therapy. Rituximab treatment was well tolerated. Two patients discontinued the drug due to leukopenia; however, both patients reinstituted rituximab at modified doses.

Conclusion

Rituximab therapy was effective in controlling granulomatous ocular disease in most cases. The drug was corticosteroid-sparing and effective in refractory cases, with no severe adverse events encountered.

Keywords: sarcoidosis, wegener’s, ANCA, cyclophosphamide

Introduction

Both sarcoidosis and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis can be associated with granulomatous inflammation of the eye, which can present as episcleritis or iritis.1,2 While both conditions can lead to orbital inflammation, sarcoidosis more commonly causes iritis, while ANCA-associated vasculitis is more commonly associated with episcleritis.1 The administration of either local or systemic corticosteroids can be beneficial in controlling acute inflammation. Because the long-term use of corticosteroids may create significant ocular toxicity, including cataracts and glaucoma, alternative immunosuppressive treatments are desirable. The therapies evaluated include cytotoxic agents such as methotrexate and cyclophosphamide. For refractory cases, antitumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents have been effective,3–5 but these drugs are associated with significant toxicity.6,7 Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody drug that acts on CD20 cells, can be effective for the treatment of non-ocular manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis8,9 and sarcoidosis.10–12 The purpose of our study is to determine the effectiveness of rituximab for the treatment of granulomatous ocular disease.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of patients with ocular granulomatous disease treated with rituximab for at least 6 months between January 2007 and December 2011 at the University of Cincinnati Interstitial Lung Disease and Sarcoidosis Clinic. Information collected included primary diagnosis, patient demographics, prior and concurrent therapy, other disease organ involvement, and clinical outcome. The study was approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Review Board and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Following premedication with acetaminophen, antihistamines, and dexamethasone, rituximab was administered initially and then 2 weeks later. Initial dosing was 1000 mg. Most patients received additional intermittent treatment based upon clinical response. Maintenance dose was usually calculated at 375 mg/m2, and treatment was given every 4 to 8 weeks. To avoid infusion reactions, all patients initially received standard prolonged infusion; however, for patients who tolerated initial administration, rapid infusion over 60 minutes was allowed.

During the course of therapy, all patients were evaluated by one ophthalmologist (AHK) at 6 months after institution of rituximab therapy and as deemed clinically necessary. Additional ophthalmologic consultation was obtained for those patients with retinal or neurologic disease. Clinical response was defined as the ability to control all signs of inflammation in conjunction with reduction of systemic glucocorticoids and with reduction in frequency of topical therapy using glucocorticosteroids, along with the requirement for periocular steroid injections and the use of corticosteroids by the patient’s treating ophthalmologist (AHK).13

Results

Nine patients were treated and evaluated for at least 6 months during the time of the study. The underlying primary diagnosis was ANCA-associated vasculitis in five patients and sarcoidosis in four patients. Table 1 summarizes the demographic features as well as prior and concurrent treatment for these patients. All patients were receiving at least one systemic therapy upon institution of rituximab, and many patients had received multiple. All nine patients were receiving prednisone at the time of rituximab initiation. Cytotoxic therapies included methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and leflunomide. Additionally, two sarcoidosis patients had previously received infliximab, but the drug was discontinued due to recurrent infections in one case and allergic reaction in the other. Two additional patients previously treated with cyclophosphamide discontinued therapy because of infectious diseases.

Table 1.

Demographics and other systemic treatment of patients studied at time of rituximab initiation

| Number | Diagnosis | Age | Race/gender | MTX | CYC | Pred | LEF | INF | Ocular target for therapy | Average maintenance dose and frequencya | Duration therapy, months | Lung involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ANCA | 57 | w/f | Past | Current | Current | Episcleritis | 500 mg every 8 weeks | 30 | Yes | ||

| 2 | ANCA | 59 | w/m | Currentb | Current | Episcleritis | 1000 mg for two doses | 2 | Yes | |||

| 3 | ANCA | 78 | w/m | Currentb | Current | Episcleritis | 675 mg for four doses | 6 | Yes | |||

| 4 | ANCA | 63 | w/f | Past | Current | Past | Episcleritis | 635 mg every 8 weeks | 18 | No | ||

| 5 | ANCA | 41 | w/f | Current | Current | Episcleritis, orbital mass | 635 mg every 8 weeks | 11 | No | |||

| 6 | Sarcoidosis | 48 | w/f | Currentb | Current | Uveitis, orbital mass | 675 mg every 8 weeks | 48 | No | |||

| 7 | Sarcoidosis | 46 | w/f | Current | Current | Orbital mass, panuveitis | 500 mg every 4 weeks | 28 | No | |||

| 8 | Sarcoidosis | 50 | b/f | Past | Past | Current | Past | Episcleritis, panuveitis, optic neuropathy | 400 mg every 8 weeks | 24 | Yes | |

| 9 | Sarcoidosis | 47 | b/f | Current | Current | Past | Past | Panuveitis | 1000 mg every 4 weeks | 10 | Yes |

Notes:

All patients given loading dose of 1000 mg as explained in methods section;

cyclophosphamide discontinued when rituximab was initiated.

Abbreviations: MTX, methotrexate; CYC, cyclophosphamide; Pred, prednisone; LEF, leflunomide; INF, infliximab; w, white; f, female; m, male; b, black.

Lung involvement was identified in five of the nine patients, but no renal disease was detected in the ANCA-associated vasculitis patients. No other significant extraocular organ involvement was identified in the patients with sarcoidosis or ANCA-associated vasculitis.

Table 2 summarizes the clinical outcome of all nine patients. Within 6 months of instituting rituximab therapy, eight of nine patients experienced significant clinical benefit: all five ANCA-associated vasculitis patients and three of the four sarcoidosis patients. Three patients were able to discontinue all prednisone, while the remaining patients had their dosage reduced. Only one patient required continued periocular steroid injections after 6 months of rituximab therapy.

Table 2.

Clinical outcome of rituximab therapy

| Patient number | Duration therapy (months) | Initial prednisone daily dosage (mg) | Daily dosage prednisone (mg) after 6 months of rituximab | Serious adverse events encountered during rituximab therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 | 10 | 0 | Herpetic mouth ulcers |

| 2 | 12 | 10 | 0 | |

| 3 | 12 | 40 | 0 | |

| 4 | 16 | 15 | 5 | Breast cancera |

| 5 | 11 | 60 | 0 | |

| 6 | 42 | 20 | 5 | Neutropenia |

| 7 | 16 | 60 | 10 | Neutropenia |

| 8 | 23 | 30 | 20 | Staphylococcus aureus skin infections |

| 9 | 9 | 30 | 10 |

Notes:

Not felt to be caused by rituximab therapy.

Patients were treated for 12 to 41 months. At the conclusion of the study period, seven patients still required intermittent therapy. One patient treated for 1 year discontinued rituximab for more than 2 years without relapse; another patient was lost at follow-up after 1 year. Rituximab was a well-tolerated therapy with no unexpected side effects noted. Serious adverse events encountered during rituximab therapy are reported in Table 2. Two patients experienced recurrent infections, one each of herpetic mouth ulcers and skin infections. The patient with herpetic infection has since been maintained with valcyclovir therapy, with no further relapses. One patient was diagnosed with breast cancer within 3 months of starting rituximab therapy. She tolerated surgical, radiation, and hormonal therapy well without discontinuing rituximab.

Leukopenia developed in two patients. One patient, who previously received cyclophosphamide, developed severe neutropenia, and rituximab was withdrawn for 1 year. Bone marrow examination revealed no hematologic abnormalities, including myelodysplasia, and the neutropenia was fully reversible. This patient developed a relapse of her eye disease, and single-agent rituximab was reinstituted, with improvement of eye disease and no further neutropenia. In the other leukopenic patient, no further leukopenia developed after the rituximab dose was reduced and methotrexate discontinued.

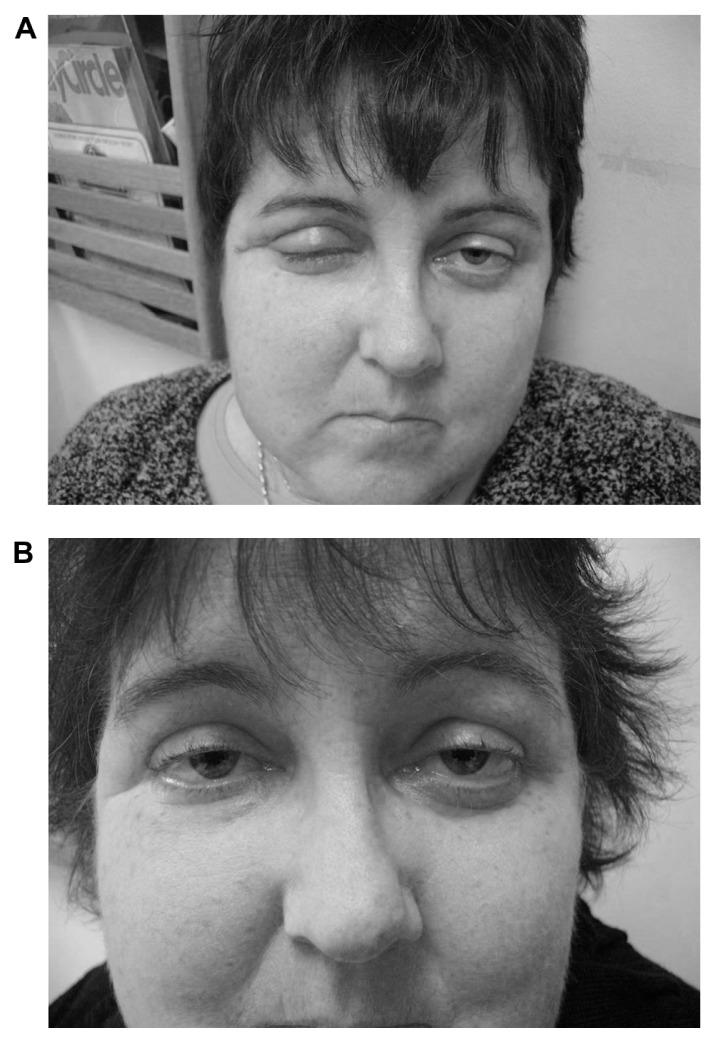

Figure 1 shows a sarcoidosis patient treated with rituximab for granulomatous eye disease. She developed refractory disease from high doses of corticosteroids and methotrexate, necessitating surgical debulking on three occasions. Initial consultation was sought for further evaluation and possible treatment with an anti-TNF agent; however, because she carried a p53 mutation encoding for Li–Fraumeni syndrome with an increased risk of malignancy, she declined anti-TNF therapy. Figure 1A shows her edematous right eye and ptosis despite 6 months of 60 mg prednisone daily and 10 mg methotrexate a week. Figure 1B shows her right eye 6 months after starting rituximab. The patient continued to receive weekly methotrexate, but prednisone was reduced to 10 mg a day.

Figure 1.

Patient 7 with retroorbital mass found to have noncaseating granulomas consistent with sarcoidosis. First image (A) shows eye swelling prior to rituximab therapy. Patient also had active anterior uveitis. She was treated with 60 mg prednisone a day and methotrexate. Second image (B) shows marked reduction of eye swelling after 6 months of rituximab therapy. Anterior uveitis had resolved. Patient had been able to reduce their dose of prednisone to 10 mg a day and continued on methotrexate. Patient provided written consent for publication of these photographs.

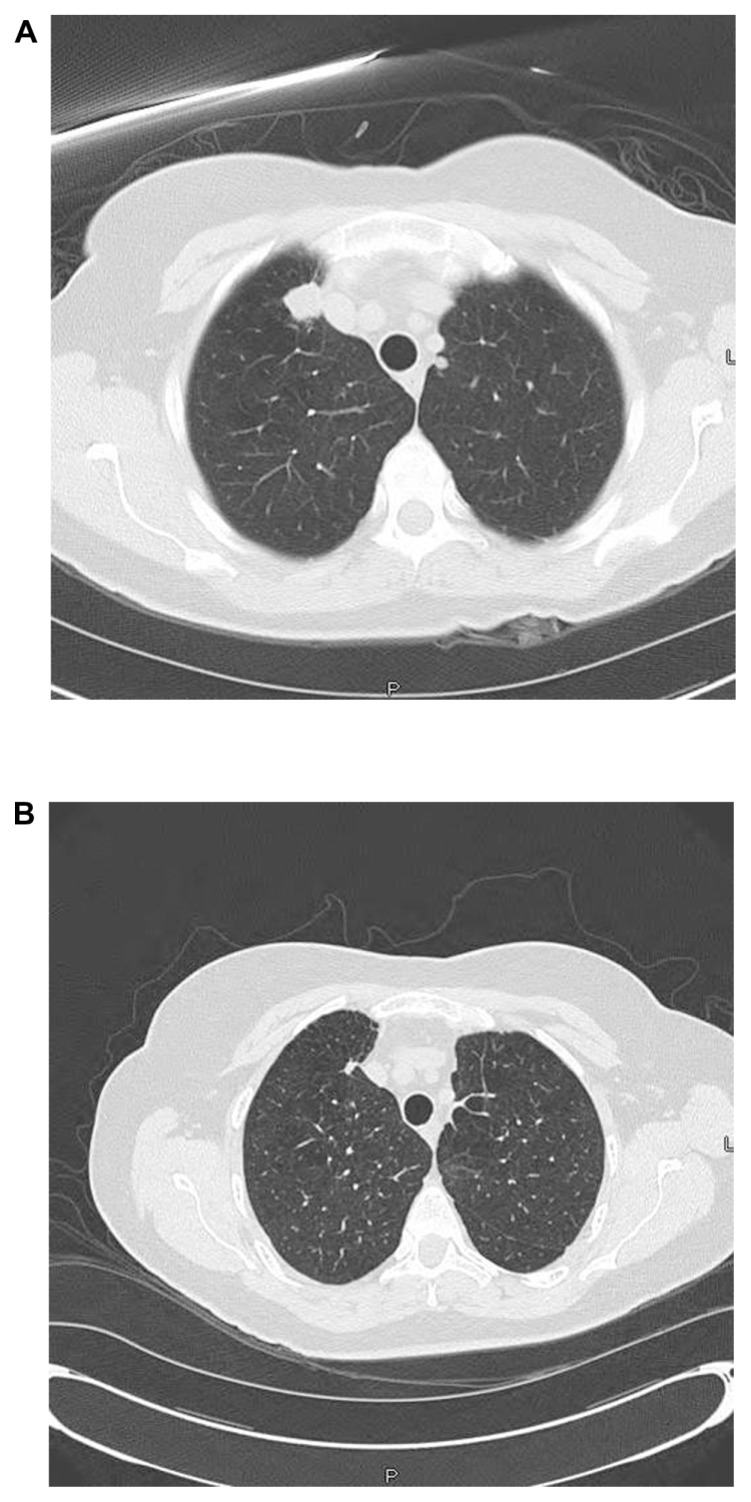

Five patients had clinically significant lung involvement at the time rituximab was instituted. This included three cases of ANCA-associated vasculitis and two cases of sarcoidosis. All five patients with lung involvement had improvement in symptoms with rituximab therapy. Computed tomography scanning prior to rituximab therapy revealed pulmonary nodules in the three ANCA-associated vasculitis patients. In all three cases, the nodules resolved with rituximab therapy. Figure 2 shows computed tomography scans for a patient with C-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive episcleritis. Although the patient initially responded to methotrexate, she developed recurrent episcleritis and new lung lesions 6 months after methotrexate withdrawal. Despite drug reinstitution, the lung lesions progressed (Figure 2A). After rituximab institution, the episcleritis resolved within 2 months, and the lung nodules markedly diminished over 4 months (Figure 2B). Corticosteroid ophthalmic drops have since been discontinued, and she has been maintained on intermittent rituximab for 2 years without further relapse.

Figure 2.

Patient 1 with episcleritis with positive C-ANCA. Methotrexate had been discontinued after 4 years of therapy. Patient developed recurrence of episcleritis and developed new lung lesions (A). No response to reinstitution of methotrexate and prednisone. Rituximab instituted with marked reduction in lung lesions (B), improvement in episcleritis, and prednisone withdrawal.

Abbreviation: C-ANCA, C-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.

Conclusion

Rituximab was successful in treating eight of nine patients with granulomatous eye disease secondary to ANCA-associated vasculitis or sarcoidosis. The involvement could be as an orbital mass, episcleritis, or uveitis. All of these manifestations have been reported with both ANCA-associated vasculitis and sarcoidosis.14,15 The drug was well tolerated, with only one patient having to discontinue it because of neutropenia. In that case, the underlying disease recurred, and she was able to restart rituximab with no further neutropenia. The response to therapy was based on the use of topical and systemic glucocorticoids. The decision to change glucocorticoid therapy was made by one ophthalmologist (AHK). We have previously used this evaluation method to assess responses to etanercept therapy for sarcoidosis.13

Prior reports have indicated a good response by 6 months for ocular disease attributed to ANCA-associated vasculitis. 8,16–21 However, at least a third of patients who received only two initial treatments relapsed within 18 months.20 Reinstitution of rituximab usually led to reestablishing a remission.19,20 Rituximab was initially reported as efficacious for lung and renal disease secondary to ANCA-associated vasculitis.8,22 Recent double-blind trials have shown similar effectiveness for rituximab, compared to cyclophosphamide for systemic ANCA-associated vasculitis.9,23 In the current study, all four patients with lung disease responded. This included three patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis and pulmonary nodules, all of whom responded to rituximab therapy (Figure 2).

The previously reported placebo-controlled trials comparing rituximab to cyclophosphamide failed to show significant differences in toxicity between rituximab and cyclophosphamide. 9,23 However, these studies were of relatively short duration and without long-term toxicity assessment. Long-term toxicity data is available for both agents in the malignant and nonmalignant setting. As an alkylating agent, cyclophosphamide can be responsible for temporary or permanent amenorrhea and concomitant fertility issues.24 In contrast, menstrual and fertility issues appear unassociated with single-agent rituximab. Long-term administration of cyclophosphamide for ANCA diseases can be associated with an increased risk of malignancy, especially bladder cancer.25 Increased malignancy risk has not been associated with rituximab administration.

There are significant toxicities associated with rituximab. These include neutropenia and increased risk of infections.26,27 The risk of neutropenia is increased with previous or concurrent administration of cytotoxic agents.28 It may also be more common in some conditions, such as ANCA-associated vasculitis.29 Both of our neutropenic cases occurred in sarcoidosis patients who had received cytotoxic agents for more than 2 years prior to the institution of rituximab. Sarcoidosis itself may affect the bone marrow, leading to neutropenia.30,31 Infection complications can be severe, but are usually reported at a rate of less than 1%.26,27,29 Patients not receiving high-dose chemotherapy for lymphoma have a lower rate of complications, even when therapy is received for more than 5 years.32 Although herpetic reactivation has been reported during rituximab therapy,33,34 the use of antiviral therapy has been effective in reducing the risk of recurrent viral infections.34

A limited number of case reports describe the benefit of rituximab for sarcoidosis.10–12 In the current series, three of four sarcoidosis patients with refractory ocular disease responded to rituximab. The one nonresponding patient had previously improved with the anti-TNF antibody infliximab, but the drug was discontinued because of recurrent infections. Although rituximab may increase the risk of a variety of infections, including viral reactivation, 26 a higher risk of serious infections appears unlikely with single-agent therapy.27 The patient continued to have recurrent skin infections, but these responded to antibiotic therapy. This patient was considered a nonresponder to rituximab, because the prednisone dosage could not be tapered below 20 mg daily.

Overall, rituximab was well tolerated in this study. Rituximab was a successful alternative to other biologic agents for the treatment of patients with ocular granulomatous disease. Future studies into the use of this drug are warranted.

Acknowledgments and disclosure

Written consent has been obtained for using patient photographs. The University of Cincinnati has received a research grant from Genentech for Dr Lower and Dr Baughman to study rituximab in pulmonary sarcoidosis. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.DeRemee RA. Sarcoidosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis: a comparative analysis. Sarcoidosis. 1994;11:7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohara K, Judson MA, Baughman RP. Clinical aspects of ocular sarcoidosis. In: Drent M, Costabel U, editors. Sarcoidosis. Wakefield, UK: The Charlesworth Group; 2005. pp. 188–209. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baughman RP, Bradley DA, Lower EE. Infliximab for chronic ocular inflammation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;43:7–11. doi: 10.5414/cpp43007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kontkanen M, Paimela L, Kaarniranta K. Regression of necrotizing scleritis in Wegener’s granulomatosis after infliximab treatment. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88:e96–e97. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Josselin L, Mahr A, Cohen P, et al. Infliximab efficacy and safety against refractory systemic necrotising vasculitides: long-term follow-up of 15 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1343–1346. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.083584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeuchi T, Tatsuki Y, Nogami Y, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety profile of infliximab in 5000 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:189–194. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.072967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pham T, Claudepierre P, Deprez X, et al. Anti-TNF alpha therapy and safety monitoring. Clinical tool guide elaborated by the Club Rhumatismes et Inflammations (CRI), section of the French Society of Rheumatology (Societe Francaise de Rhumatologie, SFR) Joint Bone Spine. 2005;72(Suppl 1):S1–S58. doi: 10.1016/s1169-8330(05)80001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keogh KA, Ytterberg SR, Fervenza FC, Carlson KA, Schroeder DR, Specks U. Rituximab for refractory Wegener’s granulomatosis: report of a prospective, open-label pilot trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:180–187. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1144OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone JH, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:221–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belkhou A, Younsi R, El Bouchti I, El Hassani S. Rituximab as a treatment alternative in sarcoidosis. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:511–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasilva V, Breuil V, Chevallier P, Euller-Ziegler L. Relapse of severe sarcoidosis with an uncommon peritoneal location after TNF alpha blockade. Efficacy of rituximab, report of a single case. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:82–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bomprezzi R, Pati S, Chansakul C, Vollmer T. A case of neurosarcoidosis successfully treated with rituximab. Neurology. 2010;75:568–570. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ec7ff9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baughman RP, Lower EE, Bradley DA, Raymond LA, Kaufman A. Etanercept for refractory ocular sarcoidosis: results of a double-blind randomized trial. Chest. 2005;128:1062–1067. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulter EL, Eleftheriou D, Sebire NJ, Edelsten C, Brogan PA. Inflammatory lesions of the orbit: a single paediatric rheumatology centre experience. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:1070–1075. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baughman RP, Lower EE, Kaufman AH. Ocular sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31:452–462. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avshovich N, Boulman N, Slobodin G, Zeina AR, Rosner I, Rozenbaum M. Refractory Wegener’s granulomatosis: effect of rituximab on granulomatous bilateral orbital involvement. Isr Med Assoc J. 2009;11:566–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez Del Pero M, Chaudhry A, Jones RB, Sivasothy P, Jani P, Jayne D. B-cell depletion with rituximab for refractory head and neck Wegener’s granulomatosis: a cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34:328–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ooka S, Maeda A, Ito H, Omata M, Yamada H, Ozaki S. Treatment of refractory retrobulbar granuloma with rituximab in a patient with ANCA-negative Wegener’s granulomatosis: a case report. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19:80–83. doi: 10.1007/s10165-008-0119-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor SR, Salama AD, Joshi L, Pusey CD, Lightman SL. Rituximab is effective in the treatment of refractory ophthalmic Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1540–1547. doi: 10.1002/art.24454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshi L, Lightman SL, Salama AD, Shirodkar AL, Pusey CD, Taylor SR. Rituximab in refractory ophthalmic Wegener’s granulomatosis: PR3 titers may predict relapse, but repeat treatment can be effective. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2498–2503. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheung CM, Murray PI, Savage CO. Successful treatment of Wegener’s granulomatosis associated scleritis with rituximab. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1542. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.075689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henes JC, Fritz J, Koch S, et al. Rituximab for treatment-resistant extensive Wegener’s granulomatosis – additive effects of a maintenance treatment with leflunomide. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1711–1715. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones RB, Tervaert JW, Hauser T, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:211–220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lower EE, Blau R, Gazder P, Tummala R. The risk of premature menopause induced by chemotherapy for early breast cancer. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8:949–954. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talar-Williams C, Hijazi YM, Walther MM, et al. Cyclophosphamide- induced cystitis and bladder cancer in patients with Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:477–484. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-5-199603010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aksoy S, Dizdar O, Hayran M, Harputluoglu H. Infectious complications of rituximab in patients with lymphoma during maintenance therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:357–365. doi: 10.1080/10428190902730219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salliot C, Dougados M, Gossec L. Risk of serious infections during rituximab, abatacept and anakinra treatments for rheumatoid arthritis: meta-analyses of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:25–32. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.083188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanini S, Molloy AC, Fine PE, Prentice AG, Ippolito G, Kibbler CC. Risk of infection in patients with lymphoma receiving rituximab: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2011;9:36. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tesfa D, Ajeganova S, Hagglund H, et al. Late-onset neutropenia following rituximab therapy in rheumatic diseases: association with B lymphocyte depletion and infections. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2209–2214. doi: 10.1002/art.30427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lower EE, Smith JT, Martelo OJ, Baughman RP. The anemia of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis. 1988;5:51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Browne PM, Sharma OP, Salkin D. Bone marrow sarcoidosis. JAMA. 1978;240:43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Popa C, Leandro MJ, Cambridge G, Edwards JC. Repeated B lymphocyte depletion with rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis over 7 yrs. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:626–630. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cabanillas F, Liboy I, Pavia O, Rivera E. High incidence of non-neutropenic infections induced by rituximab plus fludarabine and associated with hypogammaglobulinemia: a frequently unrecognized and easily treatable complication. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1424–1427. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Treon SP, Ioakimidis L, Soumerai JD, et al. Primary therapy of Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia with bortezomib, dexamethasone, and rituximab: WMCTG clinical trial 05-180. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3830–3835. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]