Abstract

Focusing heat delivery while minimizing collateral damage to normal tissues is essential for successful nanoparticle-mediated laser-induced thermal cancer therapy. We present thermal maps obtained via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) characterizing laser heating of a phantom tissue containing a multiwalled carbon nanotube inclusion. The data demonstrate that heating continuously over tens of seconds leads to poor localization (~ 0.5 cm) of the elevated temperature region. By contrast, for the same energy input, heat localization can be reduced to the millimeter rather than centimeter range by increasing the laser power and shortening the pulse duration. The experimental data can be well understood within a simple diffusive heat conduction model. Analysis of the model indicates that to achieve 1 mm or better resolution, heating pulses of ~ 2s or less need to be used with appropriately higher heating power. Modeling these data using a diffusive heat conduction analysis predicts parameters for optimal targeted delivery of heat for ablative therapy.

Keywords: carbon nanotube, MR thermometry, photothermal therapy, heat localization, diffusive heat model, MR Imaging, proton resonance shift

1. Introduction

Because magnetic and metallic nanoparticles can absorb energy from external electromagnetic fields and subsequently release this energy to their immediate surroundings as heat, there has been great interest in the development of nanoparticles as targeted thermal agents for medical therapies (West et al., 2003; O'Neal et al., 2004; Hamaguchi et al., 2003) and in biotechnology (Langer et al., 2003). Materials effective in generating heat in response to excitation by laser-emitted near-infrared radiation include gold (West et al., 2011), fullerene-based nanoparticles (Iancu and Mocan, 2011) as well as single (SWCNT) and multiwalled (MWCNT) carbon nanotubes (Biris et al., 2009; Dai et al., 2005; Ding et al., 2011; Fisher et al., 2010; Burke et al., 2009). Approaches using these materials typically involve irradiation of nanoparticles dispersed homogeneously throughout a macroscopic volume, resulting in gradual heating over tens of seconds (Feldheim et al., 2003; Lyon and Jones, 2003; Rosensweig, 2002).

Reproducible control of the spatial and temporal distribution of heat to ablate tumors is critical to minimizing collateral damage to normal cells and tissues (Boldor et al., 2010). Although it may be possible to localize heat on the cellular level under some conditions (Biris et al., 2009; Zharov et al., 2005; Vitetta et al., 2011; Anderson and Parrish, 1983), sustained heating of nanoparticles dispersed across a tumor volume under conditions typically used for thermal ablation produces a global temperature rise orders of magnitude larger than the localized temperature rise near each particle (Keblinski et al., 2006). Thus, a limitation of current approaches to nanoparticle mediated photothermal therapy is that due to heat delocalization, temperature field localization can be achieved only over macroscopic, ~ centimeter size regions (Boldor et al., 2010), resulting in damage to healthy tissue surrounding the tumor.

Theoretically, this limitation can be overcome with the use of high-powered, pulsed lasers, which can achieve rapid (pico to nanosecond time scales) heating of nanoparticles or intracellular structures (Anderson and Parrish, 1983) and result in nanoscale temperature localization (Pustovalov and Babenko, 2004; Plech et al., 2003; Hartland et al., 2004; Ge et al., 2005; Anderson and Parrish, 1983). However, nano or picosecond pulsed lasers are not commonly available in clinical environments, and there are virtually no reports of in vivo cancer therapy studies with this approach.

We and others previously have shown that multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) are effective NIR transducers for laser induced thermal therapy, allowing greater heat generation and localization within a tumor target than laser irradiation alone (Biris et al., 2009; Dai et al., 2005; Ding et al., 2011; Fisher et al., 2010; Burke et al., 2009). Here, we extend these findings through the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) thermography to demonstrate that for a fixed concentration of nanoparticles and a fixed laser energy input, the use of a higher power and a shorter duration laser pulse leads to a greater peak temperature and improved localization of the temperature field than a longer duration, lower power pulse. We then model these data using a diffusive heat conduction analysis to predict parameters for optimal targeted delivery of heat for ablative therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phantoms

Amide-functionalized (PD15L1-5-NH2, lot number: 60809) MWCNTs purchased from NanoLab (Waltham, MA). MWCNTs (2 mg/ml) were suspended in sterile saline with 1% DSPE-PEG (Avanti Polar Lipids) through probe tip (Branson). Average length of MWCNTs was 591 ± 462 nm and average diameter was 29 ± 11 nm. Prior to use, the nanotubes were bath sonicated for 15 minutes and the dispersion stability was monitored by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Malvern Zetasizer S (Malvern Instruments). DLS measurements indicated a single peak with a zave diameter of 537 nm and a polydispersity of 0.454. MWCNTs were homogeneously distributed (100 µg/ml) in a 2% alginate (w/vol) phantom consisting of a spherical, 0.5 cm diameter inclusion which was then embedded in a larger, nanotube-free, 3 cm diameter, alginate cylinder. The phantom was placed in a mold and cross-linked for 3 days in a 1% w/vol solution of calcium chloride (Sigma).

2.2. Laser irradiation

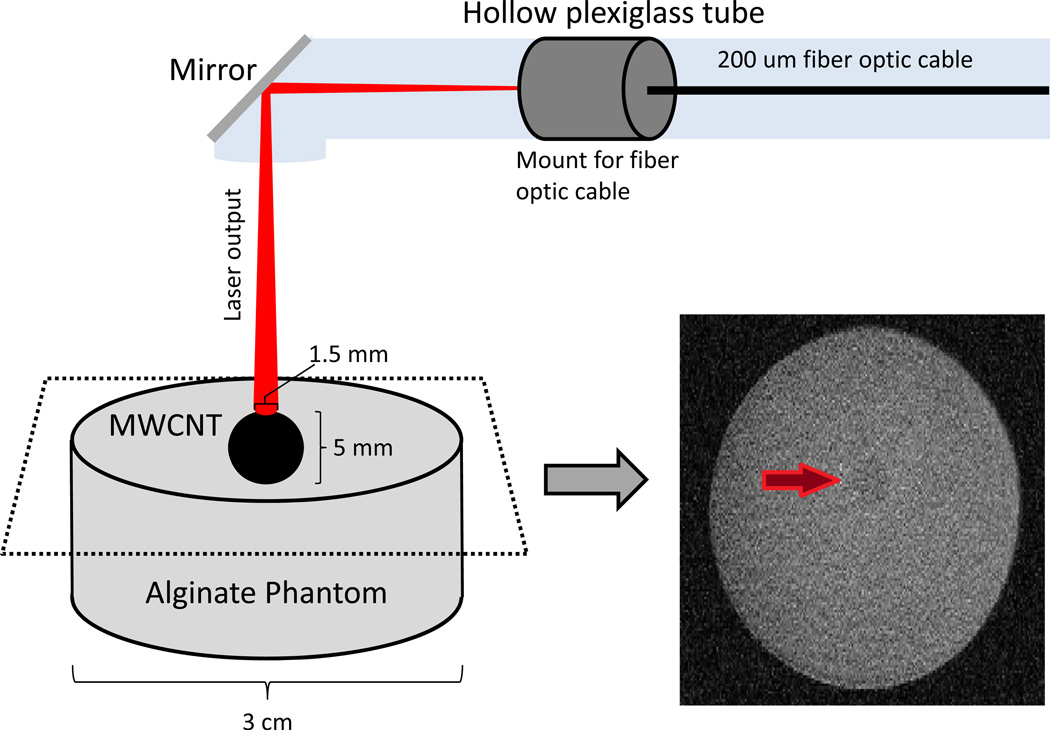

A YAG laser tuned to 1064 nm (IPG Photonics Model YLR-20-1064-LP) operated in continuous mode was used as the NIR source. The beam from the output collimator of the laser was condensed into a fiber optic cable (0.2 mm inner diameter) which was mounted into the center of a plexiglass tube designed to sit within the bore of the MRI magnet. The beam was directed at an optical mirror and reflected 90° downward toward the center of the MWCNT inclusion in the tissue phantom (Figure 1). Measurement of the spot size of a red guide laser emitted by the YLR-20-1064-LP indicated that the laser beam diameter expanded from 0.2 mm at the fiber output to 1.5 mm at the surface of the phantom. Since this spot size is far smaller than the MWCNT target, for the purposes of dosimetry, we assume that 100% of the deposited energy was absorbed by the target. A fixed total laser output energy of 192 J was used for heating studies, emitted in either a single low power, longer duration laser pulse (6 W peak power, 32 seconds), or a higher power, shorter duration laser pulse (20 W peak power, 9.6 seconds). The laser was turned on once for 9.6 seconds or 32 seconds for short and long pulse heating, respectively. The laser power at the tissue phantom surface was measured using a S-1439 Fieldmate laser power meter and PM30 sensor (both from Coherent). Power measurements indicated that the actual power received by the phantom was 25% of the power initially emitted from the laser due to losses caused by condensing the beam into the fiber optic cable and attenuation by the reflecting mirror, and thus the actual energy reaching the target was only 48 J.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the experimental design. A 2% alginate (w/vol) tissue phantom, consisting of a spherical, 0.5 cm diameter inclusion in which MWCNTs were homogeneously distributed (100 µg/ml) was embedded in a larger, nanotube-free, 3 cm diameter, alginate cylinder. An external laser beam was directed toward the center of the MWCNT-containing inclusion via a 0.2 mm diameter optical fiber. A YAG laser tuned to 1064 nm served as the laser source. On the right of the figure is a high-resolution, coronal MR image across the phantom using a spin-echo sequence to identify the geometry for use in MR thermometry studies.

2.2. MRI thermometry

To monitor changes in temperature, we used proton resonance frequency (PRF) MR temperature mapping (reviewed in (Rieke and Pauly, 2008)). This technique is based on the PRF shift that occurs when temperature rises and hydrogen bonds break between water molecules in tissue (Rieke and Pauly, 2008). This frequency shift is reflected in the phase of the proton MR signal and varies linearly with temperature changes. When the temperature changes from T to T+ΔT, the phase shift of the MR signal can be expressed as:

| (1) |

where, γ is gyromagnetic ratio, α is the rate by which the electron screening constant changes with temperature (0.01 ppm/°C), T is temperature, B0 is the magnetic field strength, and TE is echo time of the MR acquisition sequence. Thus, by acquiring two MR signals at sequential time points, the temperature change ΔT can be calculated from the MR phase shift. Temperature mapping experiments were performed using a 7T Bruker Biospin MR system. For our initial study, we obtained a high-resolution, coronal MR image across the phantom using a spin-echo sequence to identify the geometry (Figure 1) followed by a low-resolution gradient-echo scan to detect the temperature-induced phase difference within the phantom. To achieve consistency in the experimental system, external laser control was integrated into Bruker’s MR software to allow the laser power, start time and pulse duration to be prescribed through the scanner’s interface.

2.3. Thermal dose calculations

Thermal dose typically is expressed as the cumulative equivalent minutes at 43 °C (CEM43) (Sapareto and Dewey, 1984; Thrall et al., 2000). Therefore, we generated a thermal dose map of our phantom calculated from the phase shift (ΔΦ) of the 1H MR signal as the temperature rose during laser treatment to determine if the short or long pulse treatment provided differential therapeutic benefit. If we assume the body temperature is 37 °C, CEM43 can be expressed as:

| (2) |

where, n is the loop counter of the repeated MR scans, R is empirical constant (R=0 when ΔT<2 °C; R=0.25 when 2<ΔT<6 °C; R=0.5 when ΔT>6 °C. ΔT is temperature increase above 37 °C), γ is gyromagnetic ratio, α is the rate of electron screening constant changes with temperature (0.01 ppm/°C), B0 is magnetic field strength, TE is echo time, trep is the MR scan time per repetition scan. For every trep seconds, a temperature map and a dose map are calculated. After the laser was turned off, we continued to capture temperature information in order to determine the final thermal dose. CEM43T90 (calculated from the 10th percentile of temperature distribution) was also used to correlate thermal dose with pathologic response (Thrall et al., 2000). Conclusions were confirmed by calculating cell death resulting from thermal injury using the Arrhenius damage integral (Chang, 2010), which quantifies damage using first order kinetics to relate temperature and time in a non-linear fashion to an equivalent heating time at a fixed temperature. Thermal necrosis is predicted to begin when the Arrhenius integral is 1 (63% cell death). Ninety-nine percent of cells are predicted to die when the Arrhenius integral is 4.6.

2.4. Diffusive heat conduction model

The governing equation of diffusive heat flow is:

| (3) |

where, λ is the thermal conductivity, T(x, t) is the spatially and time dependent temperature field, and c is the heat capacity per unit volume. The dq/dt term in Eq. 3 represents the heat power density generated by the laser radiation. The ratio of the heat capacity to thermal conductivity is also known as thermal diffusivity, DT. A simple consideration of the diffusive process allows estimation of the heat diffusion spreading distance, L, of a localized heat source in 3 dimensional media. L is as a function of heating time, t, and is given by:

| (4) |

In the calculations we assumed DT= 0.15 mm2/s (Ge et al., 2005) and λ = 0.5 W/(m-K). Considering that in the MWCNT region the volume fraction of MWCNTs is less than 0.1 %, it is reasonable to assume that DT and λ are the same throughout the sample. Also, in the calculations the diameter of the laser-heating beam was taken to be 1.5 mm as shown in figure 1. We used the fit to the experimental data for t=32 s to calibrate the strength of the heat source term in Eq. 3. For the finite difference calculations we used a cubic mesh with a mesh size of 0.31 mm, which was selected to coincide with the experimental resolution. We performed a test calculation using a two-times smaller mesh size and observed essentially the same results as those described above, except for very early times (less than 0.1 seconds) when the temperature gradient near the source is very high. The time resolution for these calculations was 0.02 seconds. We also verified in a test calculation that using half of this time step also leads to the same results, while using time steps of 0.06 seconds or greater leads to numerical instabilities. The parameters used for the final analysis are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters used for diffusive heat conduction modeling

| Simulation box sizes: | 3.1 cm × 3.1 cm × 3.1 cm |

| Boundary conditions: | Adiabatic |

| Cubic mesh size: | 0.31 mm3 |

| Time increment: | 0.02 s |

| Laser beam diameter: | 1.5 mm |

| Thermal diffusivity of the phantom: | 0.15 mm2/s |

| Thermal conductivity of the phantom: | 0.5 W/m-K |

3. Results and Discussion

To mimic the accumulation of nanoparticles in a tumor surrounded by normal tissue, we prepared an alginate tissue phantom with an MWCNT inclusion (figure 1). The MWCNT inclusion was externally irradiated by a 1064 nm fiber laser using either a low power, longer duration laser pulse (6 W peak power, 32 s), or a higher power, shorter duration laser pulse (20 W peak power, 9.6 s). Hereafter, we will refer to these as the long pulse and short pulse, respectively. It should be noted that these irradiation parameters are consistent with those typically used clinically, in which patients may be exposed to continuous NIR irradiation of 10–15 W for 30–180 s for tumor treatment (Carpentier et al., 2011). We used PRF MR thermometry to generate a temperature map over time of our phantom to determine if the short or long pulse treatment provided a differential therapeutic benefit.

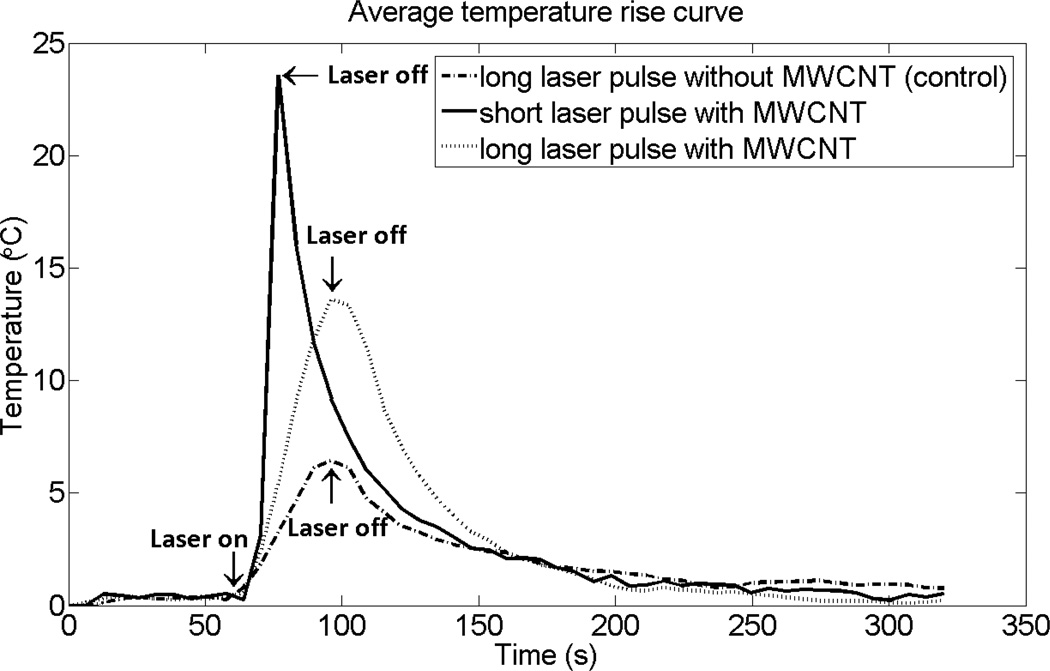

Figure 2 shows the time evolution of the average temperature change achieved in the 0.5 cm MWCNT inclusion following exposure to long and short laser pulses. As a control, an alginate phantom that did not contain MWCNTs also was heated using the long laser pulse and the temperature curve from this experiment is also shown in figure 2. In the absence of MWCNTs, the average temperature rise following the long laser pulse was less than 7 °C. By comparison, the average temperature in the MWCNT phantom increased by 17 °C following the long pulse, and by 25 °C for the short pulse, although the same input energy was applied in all cases. The temperature increased approximately linearly with time in response to both long and short pulse irradiation and the rate of the average temperature increase was 1.89 °C/s and 0.38 °C/s for the short and long pulse heating, respectively. The ratio of these heating rates is about 5 and is significantly greater than the ratio of heating powers, which is about 3 (20 W/6 W). This suggests that during long pulse heating, more heat diffuses away from the heated region, leading to a lower temperature increase in the target region and a higher temperature increase in adjacent regions. Temperature maps from a coronal slice across the MWCNT inclusion and surrounding nanotube-free phantom generated at the time the laser was turned off clearly show that heat is more localized following the short pulse treatment (figure 3). Thus, for a given amount of energy, short pulse heating leads to a higher maximum temperature, a more rapid rate of temperature increase, and more localized heating.

Figure 2.

Time evolution of the average temperature achieved in the 0.5 cm MWCNT inclusion or alginate alone following laser irradiation. The phantoms were heated using a fixed laser input energy (192 J) delivered via an external fiber laser using a lower power, longer duration laser pulse (6 W, 32 secs; long laser pulse) or a higher power, shorter duration pulse (20 W, 9.6 sec; short laser pulse). The data are presented as the average rise in temperature over baseline within the nanotube inclusion as calculated by PRF MR thermometry from a coronal slice across the nanotube containing phantom in which the maximum temperature rise was detected.

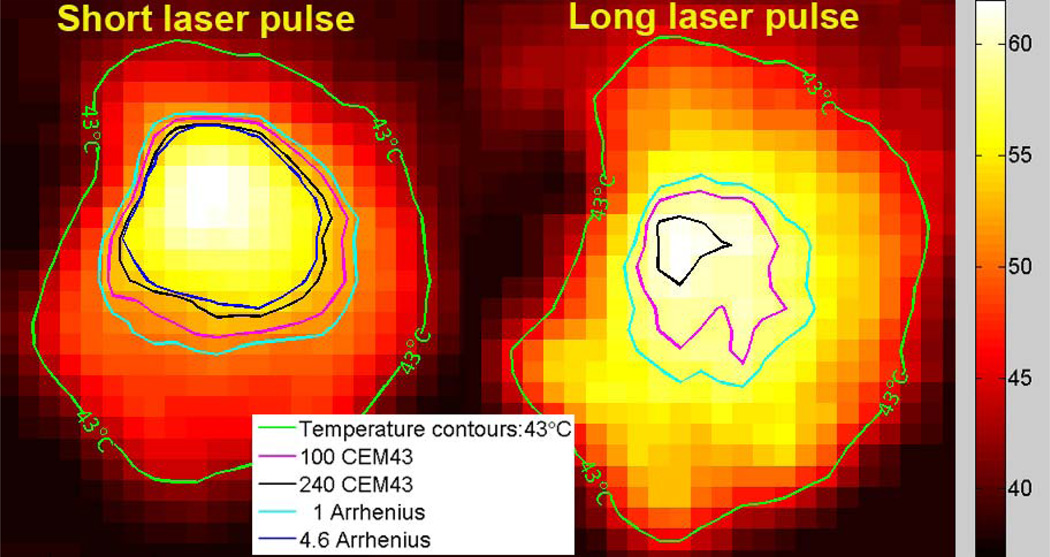

Figure 3.

Temperature maps calculated by PRF MR thermometry of the MWCNT inclusion and surrounding nanotube-free phantom. The data are presented as the temperature in each voxel from a coronal slice across the nanotube containing phantom at the time when the maximum temperature rise was detected. For the purpose of temperature and thermal dose calculations, the baseline temperature was assumed to be 37 °C. A temperature contour for which the peak temperature reached 43 °C (green curve) is shown. Thermal damage contours calculated for the 100CEM43 (pink curve) and the 240CEM43 thresholds (blue curve) are shown. Contours calculated using the Arrhenius damage integral are shown for comparison. Thermal necrosis is predicted to begin when the Arrhenius integral equals 1 (light blue curve), which is roughly equivalent to 100CEM43. Ninety-nine percent of cells are predicted to die when the Arrhenius integral equals 4.6 (dark blue curve), which is roughly equivalent to 240CEM43. Note that 99% cell death as calculated by the Arrhenius damage integral was not achieved using long laser pulse heating.

We next used the PRF MR thermometry data to compare the likely therapeutic efficacy of short and long pulse treatments using a model of thermal tissue damage based on thermal dose (Rieke and Pauly, 2008). Thermal dose typically is expressed as the cumulative equivalent minutes at 43 °C (CEM43) (Sapareto and Dewey, 1984; Thrall et al., 2000). The thermal dose required for total necrosis ranges from 25 to 240 min at 43°C for biological tissues (Daum and Hynynen, 1998). We used two measures of thermal dose based on CEM43: (1) 240CEM43, indicating the volume in the specimen exposed to at least a thermal dose equivalent to 240 minutes at 43°C and therefore likely necrotic; (2) CEM43T90, which defines the thermal dose in a volume within which the measured points were exposed to an increase in temperature of at least 10% of the maximum temperature achieved following heating (Thrall et al., 2000).

We observe that short pulse heating resulted in about 40% of the MWNT-containing region reaching the 240CEM43 necrosis threshold as illustrated by region enclosed by the blue line in figure 3. In contrast, less than 2% of the MWNT region reached the necrosis threshold following long pulse heating, despite the fact that the thermal energy delivered was the same in both cases. Quantification of the thermal dose by CEM43T90 measurement also demonstrated that a much higher dose was obtained from the short pulse treatment as compared to the long pulse (143.5 CEM43T90 vs. 29.7 CEM43T90).

The Arrhenius damage integral is an alternative method to estimate accumulated thermal dose and the resulting probability of treatment efficacy (Chang, 2010). This equation can be written as:

| (5) |

where Ω(t) is the degree of tissue injury at time t, R is the universal gas constant, T is temperature, A is a "frequency" factor, and ΔE is the activation energy for the irreversible damage reaction (cell death). We applied previously verified Arrhenius parameters for thermally induced cell death in the brain (ΔE=5.064 × 105 J/mol; A=2.984 × 1080 s−1) (Sherar et al., 2000), and used equation 5 to support our conclusions. As seen in figure 3, the region in which 99% cell death is predicted in response to short pulse heating calculated using the Arrhenius method was very similar to the calculated 240CEM43 (lethal dose) region, suggesting that these are both good measures of cell death. Similar to our observations with 240CEM43 calculations, solving the Arrhenius damage integral also demonstrated short pulse heating to be substantially more effective than long pulse heating: in contrast to the substantial region of cell death obtained using a short laser pulse, there was no region of 99% cell death in response to long pulse heating (figure 3).

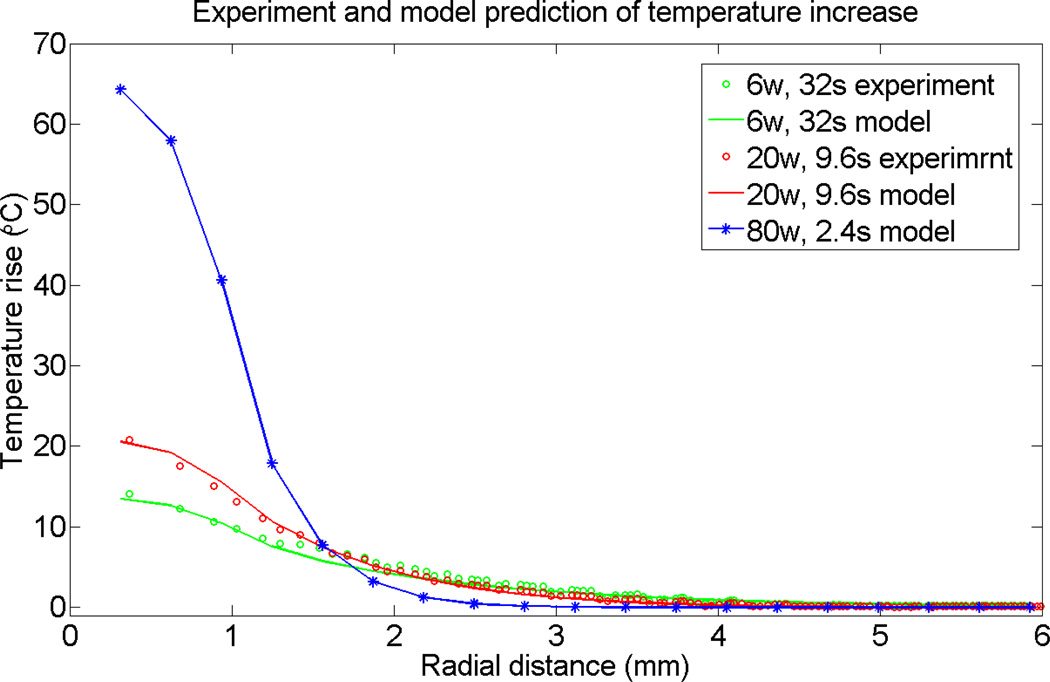

We next tested whether a conductive heat flow analysis could be used to model and therefore generalize these results. A finite difference numerical method was used to solve the heat flow equation in 3 dimensions, mimicking the experimental geometry depicted in figure 1. Assuming that the thermal diffusivity of the phantom was 0.15 mm2/s (Valvano et al., 1985), one obtains a heat diffusion spreading distance L = 5.4 mm for the long pulse, and L = 2.9 mm for the short pulse. This clearly shows that for the long pulse, more heat spreads from the heated spot, leading to a lower temperature increase and poorer localization of the elevated temperature region. The model also illustrates that to localize heating with a spatial resolution of ~ 1 mm or smaller, the heating time would need to be reduced to ~ 2 s or less.

To test the validity of the heat diffusion model in predicting MWCNT-mediated thermal responses, we compared predictions of the heat diffusion model with experimental results. According to the data in figure 3, the distribution of heat sources and/or local thermal conductivity is not quite homogenous, leading to a non-axisymmetric temperature distribution. Since the exact characteristics the media are not known, as an approximation we assumed an axisymmetric heat source and homogenous thermal conductivity and heat capacity. Due to sample/laser beam symmetry, the temperature map has a cylindrical symmetry in the calculations. We performed angular averaging to compare calculated and experimental results, and indeed, as seen on figure 4, we obtained very good agreement. We attribute this good agreement to effective homogenization of the experimental data via angular averaging. Thus, for the short pulse, the temperature peak value is significantly larger at the center of the heated region. Further away from the heated region, the long pulse heating elevates the temperature more than the short pulse heating. Both observations are consistent with the concept of improved heat localization with shorter laser pulse duration.

Figure 4.

Comparison of temperature localization of experimental data to predicted values generated by a diffusive heat conduction model. The predicted results were obtained using a finite difference numerical method to solve the heat flow equation in 3 dimensions mimicking the experimental geometry depicted in Figure 1. Experimental data are presented as the temperature rise as a function of distance from the maximum temperature obtained after irradiation of the MWCNT inclusion with a long laser pulse (6 W, 32 sec; green data points) or short laser pulse (20 W, 9.6 sec; red data points). The temperature rise values generated using the mathematical model mimicking the long and short laser pulse experiments are shown by the green and red lines respectively. The model was use to predict the temperature localization resulting from irradiation of the MWCNT inclusion with a high power, “ultra-short” laser pulse (80 W, 2.4 sec (blue line; stars indicate calculated data points used to create the line) with the same total laser energy as in the short and long pulse experiments (192 J).

Next, we used the model to predict the effect of using even shorter heating pulses that, as discussed above, will lead to a temperature field resolution of 1 mm or lower. For this test case, which we refer to as ultra-short heating, we selected 80 W and 2.4 seconds, corresponding to the same total energy used in the long and short pulse cases. As shown in figure 4, using the same model and parameters as applied to short and long pulse cases, ultra-short heating produces a dramatically higher peak temperature elevation. Furthermore, the temperature is much more localized for the ultra-short pulse than is the case for short and long heating pulses, with the temperature region capable of necrosis extending less than 0.5 mm from the heated region.

In summary, we present thermal maps characterizing laser heating of a phantom tissue with MWCNT inclusions and demonstrate that heating continuously over tens of seconds leads to poor localization (~ 0.5 cm) of the elevated temperature region. Heat localization can be improved by increasing the laser power and shortening the pulse duration. The experimental data can be well understood within a simple diffusive heat conduction model. Analysis of the model indicates that to achieve 1 mm or better resolution heating, pulses of ~ 2 seconds or less should be used with appropriately higher heating power. We note that the very large temperature elevation predicted for the ultra-short pulse suggests a laser power of about 40 W and ~ 2 seconds heating are sufficient to achieve cancer ablation, indicating that the total laser energy input could be reduced two-fold without reducing efficacy.

Further study on the contribution of heat dissipation by blood and body fluids will be required to fully define optimal concentration of nanotubes and NIR irradiation parameters required for actual clinical tumor ablation planning. In this context, our heat conduction-based analysis provides an estimate of the upper limit for the thermal field localization. Nevertheless, convective heat flow should not contribute significantly to heat spreading over ultra-short heat pulses. The modeling methodology validated in this work will assist in optimizing the application of nanoparticles in thermal tumor ablation by allowing precise application of ablative heat temperatures with minimal spillover to surrounding structures.

General Summary.

Carbon nanotubes can absorb near infrared radiation (NIR) and subsequently release this energy as heat, making them useful as agents for high temperature-mediated killing of cancer. Reproducible control of both the location and duration of heat used to treat tumors is critical to minimizing collateral damage to normal cells and tissues. A limitation of current approaches to thermal therapies is that due to heat conduction away from the treatment area, the temperature rises in centimeter size regions surrounding the target, resulting in damage to healthy tissue. Here, nanotubes embedded in a tumor model are exposed to NIR and temperature changes are measured using magnetic resonance imaging thermography. Using experimental and mathematical modeling procedures, we optimize heating of carbon nanotubes for site-specific cancer killing. We demonstrate that through appropriate choice of parameters, heat localization can be reduced to the millimeter rather than centimeter range, minimizing the risk of damaging neighboring tissue.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant RO1CA12842 (SVT). BX was supported by ARRA supplement R01CA128428-02S1. R.S. was supported in part by National Institutes of Health/ National Cancer Institute training and career development grants T32CA079448 and K99CA154006.

References

- Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Selective photothermolysis: precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science. 1983;220:524–527. doi: 10.1126/science.6836297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biris AS, Boldor D, Palmer J, Monroe WT, Mahmood M, Dervishi E, Xu Y, Li Z, Galanzha EI, Zharov VP. Nanophotothermolysis of multiple scattered cancer cells with carbon nanotubes guided by time-resolved infrared thermal imaging. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2009;14 doi: 10.1117/1.3119135. 021007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldor D, Picou L, McMann C, Elzer PH, Enright FM, Biris AS. Spatio-temporal thermal kinetics of in situ MWCNT heating in biological tissues under NIR laser irradiation. Nanotechnology. 2010;21 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/43/435101. 435101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke A, Ding X, Singh R, Kraft RA, Levi-Polyachenko N, Rylander MN, Szot C, Buchanan C, Whitney J, Fisher J, Hatcher HC, D'Agostino R, Jr, Kock ND, Ajayan PM, Carroll DL, Akman S, Torti FM, Torti SV. Long-term survival following a single treatment of kidney tumors with multiwalled carbon nanotubes and near-infrared radiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:12897–12902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905195106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier A, McNichols RJ, Stafford RJ, Guichard JP, Reizine D, Delaloge S, Vicaut E, Payen D, Gowda A, George B. Laser thermal therapy: Real-time MRI-guided and computer-controlled procedures for metastatic brain tumors. Lasers Surgery and Medicine. 2011;43:943–950. doi: 10.1002/lsm.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang IA. Considerations for thermal injury analysis for RF ablation devices. The open biomedical engineering journal. 2010;4:3–12. doi: 10.2174/1874120701004020003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai HJ, Kam NWS, O'Connell M, Wisdom JA. Carbon nanotubes as multifunctional biological transporters and near-infrared agents for selective cancer cell destruction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:11600–11605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502680102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daum DR, Hynynen K. Thermal dose optimization via temporal switching in ultrasound surgery. Ieee Transactions on Ultrasonics Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control. 1998;45:208–215. doi: 10.1109/58.646926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Singh R, Burke A, Hatcher H, Olson J, Kraft RA, Schmid M, Carroll D, Bourland JD, Akman S, Torti FM, Torti SV. Development of iron-containing multiwalled carbon nanotubes for MR-guided laser-induced thermotherapy. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011;6:1341–1352. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldheim DL, Lowe LB, Brewer SH, Kramer S, Fuierer RR, Qian GG, Agbasi-Porter CO, Moses S, Franzen S. Laser-induced temperature jump electrochemistry on gold nanoparticle-coated electrodes. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:14258–14259. doi: 10.1021/ja036672h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JW, Sarkar S, Buchanan CF, Szot CS, Whitney J, Hatcher HC, Torti SV, Rylander CG, Rylander MN. Photothermal response of human and murine cancer cells to multiwalled carbon nanotubes after laser irradiation. Cancer Research. 2010;70:9855–9864. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge ZB, Kang YJ, Taton TA, Braun PV, Cahill DG. Thermal transport in Au-core polymer-shell nanoparticles. Nano Letters. 2005;5:531–535. doi: 10.1021/nl047944x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi S, Tohnai I, Ito A, Mitsudo K, Shigetomi T, Ito M, Honda H, Kobayashi T, Ueda M. Selective hyperthermia using magnetoliposomes to target cervical lymph node metastasis in a rabbit tongue tumor model. Cancer Science. 2003;94:834–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartland GV, Hu M, Petrova H. Investigation of the properties of gold nanoparticles in aqueous solution at extremely high lattice temperatures. Chemical Physics Letters. 2004;391:220–225. [Google Scholar]

- Iancu C, Mocan L. Advances in cancer therapy through the use of carbon nanotube-mediated targeted hyperthermia. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2011;6:1675–1684. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S23588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keblinski P, Cahill DG, Bodapati A, Sullivan CR, Taton TA. Limits of localized heating by electromagnetically excited nanoparticles. Journal of Applied Physics. 2006;100 054305. [Google Scholar]

- Langer R, LaVan DA, McGuire T. Small-scale systems for in vivo drug delivery. Nat Biotechnology. 2003;21:1184–1191. doi: 10.1038/nbt876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon LA, Jones CD. Photothermal patterning of microgel/gold nanoparticle composite colloidal crystals. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:460–465. doi: 10.1021/ja027431x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neal DP, Hirsch LR, Halas NJ, Payne JD, West JL. Photo-thermal tumor ablation in mice using near infrared-absorbing nanoparticles. Cancer Letters. 2004;209:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plech A, Kurbitz S, Berg KJ, Graener H, Berg G, Gresillon S, Kaempfe M, Feldmann J, Wulff M, von Plessen G. Time-resolved X-ray diffraction on laser-excited metal nanoparticles. Europhysics Letters. 2003;61:762–768. [Google Scholar]

- Pustovalov VK, Babenko VA. Optical properties of gold nanoparticles at laser radiation wavelengths for laser applications in nanotechnology and medicine. Laser Physics Letters. 2004;1:516–520. [Google Scholar]

- Rieke V, Pauly KB. MR thermometry. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2008;27:376–390. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosensweig RE. Heating magnetic fluid with alternating magnetic field. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 2002;252:370–374. [Google Scholar]

- Sapareto SA, Dewey WC. Thermal dose determination in cancer therapy. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 1984;10:787–800. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(84)90379-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherar MD, Moriarty JA, Kolios MC, Chen JC, Peters RD, Ang LC, Hinks RS, Henkelman RM, Bronskill MJ, Kucharcyk W. Comparison of thermal damage calculated using magnetic resonance thermometry, with magnetic resonance imaging post-treatment and histology, after interstitial microwave thermal therapy of rabbit brain. Physic in Medicine and Biology. 2000;45:3563–3576. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/12/304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrall DE, Rosner GL, Azuma C, Larue SM, Case BC, Samulski T, Dewhirst MW. Using units of CEM 43 degrees C T-90, local hyperthermia thermal dose can be delivered as prescribed. International Journal of Hyperthermia. 2000;16:415–428. doi: 10.1080/026567300416712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valvano JW, Cochran JR, Diller KR. Thermal-Conductivity and Diffusivity of Biomaterials Measured with Self-Heated Thermistors. International Journal of Thermophysics. 1985;6:301–311. [Google Scholar]

- Vitetta ES, Marches R, Mikoryak C, Wang RH, Pantano P, Draper RK. The importance of cellular internalization of antibody-targeted carbon nanotubes in the photothermal ablation of breast cancer cells. Nanotechnology. 2011;22 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/9/095101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JL, Hirsch LR, Stafford RJ, Bankson JA, Sershen SR, Rivera B, Price RE, Hazle JD, Halas NJ. Nanoshell-mediated near-infrared thermal therapy of tumors under magnetic resonance guidance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:13549–13554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JL, Kennedy LC, Bickford LR, Lewinski NA, Coughlin AJ, Hu Y, Day ES, Drezek RA. A New Era for Cancer Treatment: Gold-Nanoparticle-Mediated Thermal Therapies. Small. 2011;7:169–183. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zharov VP, Galitovskaya EN, Johnson C, Kelly T. Synergistic enhancement of selective nanophotothermolysis with gold nanoclusters: Potential for cancer therapy. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2005;37:219–226. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]