Abstract

Background

Zanzibar has recently undergone a rapid decline in Plasmodium falciparum transmission following combined malaria control interventions with artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) and integrated vector control. Artesunate-amodiaquine (ASAQ) was implemented as first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in Zanzibar in 2003. Resistance to amodiaquine has been associated with the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) alleles pfcrt 76T, pfmdr1 86Y, 184Y and 1246Y. An accumulation of these SNP alleles in the parasite population over time might threaten ASAQ efficacy.

The aim of this study was to assess whether prolonged use of ASAQ as first-line anti-malarial treatment selects for P. falciparum SNPs associated with resistance to the ACT partner drug amodiaquine.

Methods

The individual as well as the combined SNP allele prevalence were compared in pre-treatment blood samples from patients with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria enrolled in clinical trials conducted just prior to the introduction of ASAQ in 2002–2003 (n = 208) and seven years after wide scale use of ASAQ in 2010 (n = 122).

Results

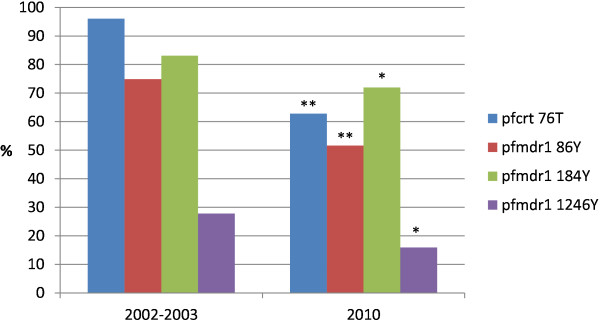

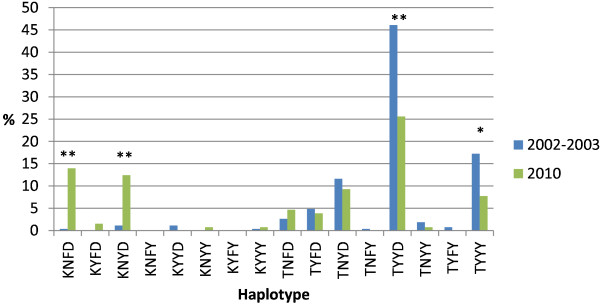

There was a statistically significant decrease of pfcrt 76T (96–63%), pfmdr1 86Y (75–52%), 184Y (83–72%), 1246Y (28–16%) and the most common haplotypes pfcrt/pfmdr1 TYYD (46–26%) and TYYY (17–8%), while an increase of pfcrt/pfmdr1 KNFD (0.4–14%) and KNYD (1–12%).

Conclusions

This is the first observation of a decreased prevalence of pfcrt 76T, pfmdr1 86Y, 184Y and 1246Y in an African setting after several years of extensive ASAQ use as first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria. This may support sustained efficacy of ASAQ on Zanzibar, although it was unexpected considering that all these SNPs have previously been associated with amodiaquine resistance. The underlying factors of these results are unclear. Genetic dilution by imported P. falciparum parasites from mainland Tanzania, a de-selection by artesunate per se and/or an associated fitness cost might represent contributing factors. More detailed studies on temporal trends of molecular markers associated with amodiaquine resistance are required to improve the understanding of this observation.

Keywords: Malaria, Plasmodium falciparum, Drug resistance, Amodiaquine, Artemisinin based combination therapy

Background

Zanzibar has recently undergone a rapid decline in Plasmodium falciparum transmission following combined malaria control interventions with artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) and integrated vector control [1,2]. In the new epidemiological context, where in vivo trials to assess ACT efficacy have been increasingly difficult to conduct due to limited number of patients, surveillance of molecular markers associated with anti-malarial drug resistance may be useful as an early warning system of development and spread of ACT resistance.

Artesunate (AS) plus amodiaquine (AQ) combination therapy (ASAQ) was implemented as first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria free of charge to all age groups through public health care facilities in Zanzibar in September 2003. AQ and its slowly eliminated active metabolite desethylamodiaquine (DEAQ) are 4-aminoquinolines and structurally related to chloroquine (CQ). Despite the similarities and putative cross-resistance in between the compounds, AQ/DEAQ has remained more efficacious [3,4].

Resistance to CQ, AQ and DEAQ has been associated with the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) alleles 76T in the P. falciparum CQ resistance transporter (pfcrt) gene and 86Y in the P. falciparum multi drug resistance 1 (pfmdr1) gene [5-13]. Pfcrt 76T has been found within different pfcrt 72–76 haplotypes. The strongest association with AQ/DEAQ resistance has been found with pfcrt SVMNT, mainly found in South America and parts of Asia, while in Africa the dominating haplotype has been pfcrt CVIET [14,15]. Further, the SNP allele pfmdr1 1246Y and the haplotype pfmdr1 (a.a. 86, 184, 1246) YYY have been selected for among recurrent infections after treatment with AQ monotherapy and ASAQ combination therapy in East Africa [10,16]. Selection and accumulation of these SNPs in the parasite population over time could potentially threaten ASAQ efficacy.

The aim of this study was to assess whether prolonged use of ASAQ as first-line anti-malarial treatment selects for P. falciparum SNPs associated with resistance to the ACT partner drug AQ.

Methods

The prevalence of pfcrt 76T, pfmdr1 86Y, 184Y and 1246Y were compared in pre-treatment blood samples collected on filter papers (3MM®, Whatman, UK). Samples were collected from individuals with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria, residing in North A (Unguja Island) and Micheweni (Pemba Island) districts in Zanzibar. Patients were enrolled in clinical trials conducted just prior to the introduction of ASAQ in 2002–2003 (n = 208) [16,17] and seven years after wide scale use of ASAQ in 2010 (n = 122) (Shakely et al. 2012, unpublished data). Malaria diagnosis was confirmed by blood smear microscopy and rapid malaria diagnostic (RDT), respectively.

DNA extraction and genotyping of samples from 2002–2003 and 2010 was performed with similar methods which have been described elsewhere [16,17]. In summary, DNA was extracted by ABI PRISM 6100 Nucleic Acid PrepStationTM (Applied Biosystems, USA) and genotyping analysis of pfcrt K76T, pfmdr1 N86Y, Y184F and D1246Y were performed through previously described PCR-RFLP methods [5,16,18]. All PCR reactions contained 1 × Taq polymerase reaction buffer, 2.5–3 mM magnesium chloride, 0.2 mM dNTP, 0.5–1 μM of each primer and 1.25 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega Corporation, USA). RFLP reaction contained 1 × NEBuffer 1/3, 0–1 × BSA and 10 U/reaction of ApoI, Tsp509 I or EcoR V restriction enzymes. PCR-RFLP products were visualized under UV transillumination (GelDoc 2000, BioRad, Hercules®, CA, USA) after 2–2.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium-bromide staining.

A mixed infection was considered to contain two P. falciparum strains, contributing with one of each SNP alleles during PCR-RFLP. In the haplotype analyses all isolates including mixed SNP results at more than one position were excluded. Allele and haplotype prevalences between 2002–2003 and 2010 were compared by chi square tests (SigmaPlot® 11.0, Systat Software Inc, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

The clinical trials were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [19] and Good Clinical Practice [20]. Informed written consent was obtained from the parents/guardians of all enrolled participants. Ethical approvals were obtained from the relevant ethical committees in Zanzibar at the time of the trials (ZHRC/GC/2002, ZMRC/RA/2005 and ZAMEC/ST/0021/09) and the Medical Ethics Committee at Karolinska Institutet (KI Dnr 03–753, KI Dnr 2005/57-31) and the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm, Sweden (2009/387-31).

Results

DNA was successfully extracted from 117/122 (96%) of the blood samples from 2010.

The individual SNP prevalences before (2002–2003) and seven years after (2010) ASAQ implementation in Zanzibar are shown in Figure 1. There was a statistically significant decrease in the prevalence of pfcrt 76T from 195/203 (96%) to 76/121 (63%) (p < 0.001), pfmdr1 86Y from 170/227 (75%) to 64/124 (52%) (p < 0.001), 184Y from 197/237 (83%) to 89/123 (72%) (p = 0.024) and 1246Y from 72/259 (28%) to 18/113 (16%) (p = 0.020).

Figure 1.

SNP frequencies in Zanzibar before (2002–2003) and seven years after (2010) ASAQ implementation. Asterisk (*) and (**) indicate statistically significant differences of p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively.

The haplotype (pfcrt K76T/pfmdr1 N86Y, Y184F, D1246Y) prevalence before and seven years after ASAQ implementation are shown in Figure 2. The most common haplotypes before implementation were TYYD and TYYY. Their respective prevalence decreased from 123/267 (46%) to 33/129 (26%) (p < 0.001) and 46/267 (17%) to 10/129 (8%) (p = 0.017). On the other hand, KNFD and KNYD increased over the time period from 1/267 (0.4%) to 18/129 (14%) (p < 0.001) and 3/267 (1%) to 16/129 (12%) (p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Haplotype (pfcrtK76T,pfmdr1N86Y, Y184F and D1246Y) frequencies in Zanzibar before (2002–2003) and seven years after (2010) ASAQ implementation. Asterisk (*) and (**) indicate statistically significant differences of p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively.

Discussion

This is the first observation of a decreased prevalence of pfcrt 76T, pfmdr1 86Y, 184Y and 1246Y in an African setting after several years of extensive ASAQ use as first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria. This may support sustained efficacy of ASAQ on Zanzibar, although it was unexpected considering that all these SNPs have previously been associated with AQ/DEAQ resistance.

The underlying factors of these results are unclear. Genetic dilution by imported P. falciparum parasites from for example mainland Tanzania could represent a contributing factor. Even though Zanzibar is a part of Tanzania, they are independent in some issues e.g. the malaria control programme. Mainland Tanzania implemented artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem®) as first-line treatment in 2006 when this ACT was widely manufactured, price had reduced and studies were shown it was safe to give children below ten kg. Artemether-lumefantrine, has shown to select for the opposite alleles i.e. pfcrt 76K, pfmdr1 86N, 184F and 1246D [21-24].

Another contributing factor may be that AS per se potentially selects for pfcrt 76K, pfmdr1 86N and 1246D, which have been associated with decreased susceptibility to the artemisinins in vitro [25,26]. Importantly however, no such selection has been shown after monotherapy with artemisinin derivatives in vivo.

A third contributing factor may be that SNPs associated with AQ resistance cause a fitness cost to the parasite, which would affect the selection pattern under different drug pressures. In competition experiments between modified isogenic clones, only differing in the pfmdr1 1246 position, pfmdr1 1246Y was found to be associated with a substantial fitness cost to the parasite (Fröberg et al. 2012, unpublished data). This could also apply on the other SNPs and also explain the haplotype results in this study. Before ASAQ implementation the most common haplotype was TYYD, indicating that the previous first-line treatment i.e. CQ mainly selected for pfcrt 76T, pfmdr1 86Y and 184Y. The second most common haplotype was TYYY, where pfmdr1 1246Y has mainly been associated with AQ/DEAQ resistance. Seven years later a significant selection of KNFD and KNYD was observed. Hence, the individual SNPs pfcrt 76T, pfmdr1 86Y and 1246Y rarely exist alone, suggesting that they may be associated with a significant fitness cost and support each other in a possibly synergistic and/or compensatory relationship, whereas pfmdr1 184Y do exist alone and might not largely affect fitness.

Finally, even though these SNPs have been selected for after AQ/ASAQ treatment, the association with AQ/DEAQ resistance may not be that strong that it will spread with prolonged wide-scale use of ASAQ.

Conclusions

Seven years after wide scale use of ASAQ as first-line treatment in Zanzibar, SNPs associated with AQ/DEAQ resistance have not been selected for. Instead, the prevalence of these SNPs has decreased, which may support sustained efficacy of this ACT as first-line treatment in Zanzibar. However, the results were unexpected, which calls for more detailed studies of temporal trends of molecular markers associated with AQ/DEAQ resistance both among symptomatic and asymptomatic P. falciparum infections to improve the understanding of this observation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GF, JPG, AM and AB conceived and designed the study. DS, AM and MIM carried out the field work. GF, LJ and UM carried out the molecular analyses. GF, LJ, UM, JPG, AB and AM analyzed the data. GF and AM wrote the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Gabrielle Fröberg, Email: gabrielle.froberg@karolinska.se.

Louise Jörnhagen, Email: louise.jornhagen@gmail.com.

Ulrika Morris, Email: ulrika.morris@ki.se.

Delér Shakely, Email: deler.shakely@ki.se.

Mwinyi I Msellem, Email: mmwinyi@hotmail.com.

José P Gil, Email: pedgil01@gmail.com.

Anders Björkman, Email: anders.bjorkman@karolinska.se.

Andreas Mårtensson, Email: andreas.martensson@ki.se.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients and their parents/guardians, as well as the health and study staff members for their participation in the clinical studies in Zanzibar.

References

- Bhattarai A, Ali AS, Kachur SP, Mårtensson A, Abbas AK, Khatib R, Al-Mafazy AW, Ramsan M, Rotllant G, Gerstenmaier JF, Molteni F, Abdulla S, Montgomery SM, Kaneko A, Björkman A. Impact of artemisinin-based combination therapy and insecticide-treated nets on malaria burden in Zanzibar. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanzibar Malaria Control Programme (ZMCP) Malaria Annual Report. http://zmcp.go.tz/docs/mar.pdf.

- Childs GE, Boudreau EF, Milhous WK, Wimonwattratee T, Pooyindee N, Pang L, Davidson DE. A comparison of the in vitro activities of amodiaquine and desethylamodiaquine against isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1989;40:7–11. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1989.40.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olliaro P, Mussano P. Amodiaquine for treating malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;CD000016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000016. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=10796468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djimde A, Doumbo OK, Cortese JF, Kayentao K, Doumbo S, Diourte Y, Dicko A, Su XZ, Nomura T, Fidock DA, Wellems TE, Plowe CV, Coulibaly D. A molecular marker for chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:257–263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101253440403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nsobya SL, Kiggundu M, Nanyunja S, Joloba M, Greenhouse B, Rosenthal PJ. In vitro sensitivities of Plasmodium falciparum to different antimalarial drugs in Uganda. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1200–1206. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01412-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duraisingh MT, Drakeley CJ, Muller O, Bailey R, Snounou G, Targett GA, Greenwood BM, Warhurst DC. Evidence for selection for the tyrosine-86 allele of the pfmdr 1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum by chloroquine and amodiaquine. Parasitology. 1997;114(Pt 3):205–211. doi: 10.1017/s0031182096008487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren G, Gil JP, Ferreira PM, Veiga MI, Obonyo CO, Björkman A. Amodiaquine resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in vivo is associated with selection of pfcrt 76 T and pfmdr1 86Y. Infect Genet Evol. 2006;6:309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picot S, Olliaro P, de Monbrison F, Bienvenu AL, Price RN, Ringwald P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence for correlation between molecular markers of parasite resistance and treatment outcome in falciparum malaria. Malar J. 2009;8:89. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys GS, Merinopoulos I, Ahmed J, Whitty CJ, Mutabingwa TK, Sutherland CJ, Hallett RL. Amodiaquine and artemether-lumefantrine select distinct alleles of the Plasmodium falciparum mdr1 gene in Tanzanian children treated for uncomplicated malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:991–997. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00875-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan V, Bray PG, Verdier-Pinard D, Johnson DJ, Horrocks P, Muhle RA, Alakpa GE, Hughes RH, Ward SA, Krogstad DJ, Sidhu AB, Fidock DA. A critical role for PfCRT K76T in Plasmodium falciparum verapamil-reversible chloroquine resistance. EMBO J. 2005;24:2294–2305. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu AB, Verdier-Pinard D, Fidock DA. Chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites conferred by pfcrt mutations. Science. 2002;298:210–213. doi: 10.1126/science.1074045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warhurst DC. Polymorphism in the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine-resistance transporter protein links verapamil enhancement of chloroquine sensitivity with the clinical efficacy of amodiaquine. Malar J. 2003;2:31. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-2-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sa JM, Twu O. Protecting the malaria drug arsenal: halting the rise and spread of amodiaquine resistance by monitoring the PfCRT SVMNT type. Malar J. 2010;9:374. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sa JM, Twu O, Hayton K, Reyes S, Fay MP, Ringwald P, Wellems TE. Geographic patterns of Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance distinguished by differential responses to amodiaquine and chloroquine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18883–18889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911317106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren G, Hamrin J, Svard J, Mårtensson A, Gil JP, Björkman A. Selection of pfmdr1 mutations after amodiaquine monotherapy and amodiaquine plus artemisinin combination therapy in East Africa. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7:562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mårtensson A, Stromberg J, Sisowath C, Msellem MI, Gil JP, Montgomery SM, Olliaro P, Ali AS, Björkman A. Efficacy of artesunate plus amodiaquine versus that of artemether-lumefantrine for the treatment of uncomplicated childhood Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1079–1086. doi: 10.1086/444460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga MI, Ferreira PE, Björkman A, Gil JP. Multiplex PCR-RFLP methods for pfcrt, pfmdr1 and pfdhfr mutations in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Cell Probes. 2006;20:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association (WMA) Declaration of Helsinki - Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html. [PubMed]

- ICH Good Clinical Practice. http://www.ich.org/products/guidelines.html.

- Sisowath C, Stromberg J, Mårtensson A, Msellem M, Obondo C, Björkman A, Gil JP. In vivo selection of Plasmodium falciparum pfmdr1 86 N coding alleles by artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem) J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1014–1017. doi: 10.1086/427997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisowath C, Ferreira PE, Bustamante LY, Dahlstrom S, Mårtensson A, Björkman A, Krishna S, Gil JP. The role of pfmdr1 in Plasmodium falciparum tolerance to artemether-lumefantrine in Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:736–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngasala BE, Malmberg M, Carlsson AM, Ferreira PE, Petzold MG, Blessborn D, Bergqvist Y, Gil JP, Premji Z, Björkman A, Mårtensson A. Efficacy and effectiveness of artemether-lumefantrine after initial and repeated treatment in children <5 years of age with acute uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in rural Tanzania: a randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:873–882. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisowath C, Petersen I, Veiga MI, Mårtensson A, Premji Z, Björkman A, Fidock DA, Gil JP. In vivo selection of Plasmodium falciparum parasites carrying the chloroquine-susceptible pfcrt K76 allele after treatment with artemether-lumefantrine in Africa. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:750–757. doi: 10.1086/596738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwai L, Kiara SM, Abdirahman A, Pole L, Rippert A, Diriye A, Bull P, Marsh K, Borrmann S, Nzila A. In vitro activities of piperaquine, lumefantrine, and dihydroartemisinin in Kenyan Plasmodium falciparum isolates and polymorphisms in pfcrt and pfmdr1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:5069–5073. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00638-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, Saliba KJ, Caruana SR, Kirk K, Cowman AF. Pgh1 modulates sensitivity and resistance to multiple antimalarials in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2000;403:906–909. doi: 10.1038/35002615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]