Abstract

Alveolar epithelial cells are considered to be the primary target of bleomycin-induced lung injury, leading to interstitial fibrosis. The molecular mechanisms by which bleomycin causes this damage are poorly understood but are suspected to involve generation of reactive oxygen species and DNA damage. We studied the effect of bleomycin on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and nuclear DNA (nDNA) in human alveolar epithelial A549 cells. Bleomycin caused an increase in reactive oxygen species production, DNA damage, and apoptosis in A549 cells; however, bleomycin induced more mtDNA than nDNA damage. DNA damage was associated with activation of caspase-3, cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, and cleavage and activation of protein kinase D1 (PKD1), a newly identified mitochondrial oxidative stress sensor. These effects appear to be mtDNA-dependent, because no caspase-3 or PKD1 activation was observed in mtDNA-depleted (ρ0) A549 cells. Survival rate after bleomycin treatment was higher for A549 ρ0 than A549 cells. These results suggest that A549 ρ0 cells are more resistant to bleomycin toxicity than are parent A549 cells, likely in part due to the depletion of mtDNA and impairment of mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathways.

Keywords: mitochondrial DNA damage, protein kinase D1, apoptosis, reactive oxygen species, fibrosis

bleomycin, an anticancer drug, is well known for causing oxidative-mediated lung injury, leading to fibroblast proliferation, collagen deposition, and distortion of lung architecture. Various types of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide radical anion (O2−), H2O2, and the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (.OH) (22) produced by bleomycin, can attack DNA of target cells (4, 13, 23, 30), resulting in single- or double-stranded DNA breaks, purine, pyrimidine, or deoxyribose modifications, and DNA cross-links that can occur in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and nuclear DNA (nDNA).

Damage to nDNA in lung cells has long been implicated in bleomycin pulmonary toxicity, contributing directly to cell death or failure of the replication of critical alveolar progenitor cells required during repair following toxicity (48). Bleomycin-induced damage to mtDNA has received much less attention but is recognized to occur (20). Damage to mtDNA has been associated with the aging process and a variety of human diseases, including Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, diabetes mellitus, and cancer (35). Also, mtDNA may be more sensitive to oxidative damage than is nDNA, resulting in oxidative base modifications, such as 8-oxoguanine and thymine glycol, abasic sites, and various other types of lesions (46). We and others have provided evidence that mtDNA damage can impair the electron transport chain, triggering the mitochondrial permeability transition and releasing apoptosis-promoting factors, thus activating the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (27, 28). This pathway is activated through diverse extracellular stresses and involves procaspase-9 activation (11), which in turn cleaves and activates downstream effector caspases (19). Among the most important regulators of the apoptotic process are members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins (2). While members such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL suppress apoptosis, other members such as Bax, Bak, and Bid promote apoptosis. In healthy cells, Bax is located in the cytoplasm, but during apoptosis, it translocates to the mitochondria. One method to study the role of mitochondria in apoptosis is to deplete cells of mtDNA by treatment with ethidium bromide (EtBr) (17); these mtDNA-depleted cells are termed, by convention, ρ0 cells. Numerous ρ0 cell lines have been generated to study important mitochondrial roles in oxidative phosphorylation, Ca2+ homeostasis alteration, ATP production, ROS generation, and, more recently, resistance to apoptosis (3, 5, 29). In addition, these cell lines have also been used to study mitochondrial protein-import function and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), which can ultimately affect signaling pathways between the mitochondria and the nucleus.

Signaling pathways are known to exist between the mitochondria and the nucleus (40), and they are known to control vital pathways essential for cell viability. The first described mitochondrion-to-nucleus signaling pathway involves the serine/threonine kinase protein kinase D1 (PKD1), which has been identified as a mitochondrial sensor for oxidative stress (38, 39). PKD1 is implicated in multiple biological processes, such as proliferation, invasion, regulation of the Golgi apparatus, and apoptosis (32). However, depending on the stimulus and the pathway, activated PKD1 can play an important role in cell survival or apoptosis. It can be activated by a variety of mechanisms, including proteolytic cleavage and phosphorylation (41). On exposure of cells to ROS, PKD1 is activated by 1) phosphorylation at Tyr463, 2) phosphorylation at Tyr95, and 3) phosphorylation at the activation loop residues Ser738 and Ser742. When activated in response to oxidative stress, it has been shown to initiate a mitochondrion-to-nucleus signaling pathway, leading to the activation of NF-κB and expression of genes promoting cellular detoxification and survival (37, 38). However, in response to DNA damage, PKD1 is activated by caspase-3, generating the 62-kDa catalytically active fragment (CF), which sensitizes cells to apoptosis (9). This was the first known example of a pathway initiated in mitochondria that protects these organelles and cells from oxidative stress-mediated damage or induces apoptosis in response to diverse genotoxic drugs (9, 42).

In view of the important role of mitochondria and mtDNA in triggering the apoptotic response to oxidant injury and DNA damage, we assessed these mitochondria-dependent pathways during bleomycin injury in A549 alveolar epithelial cells and in mtDNA-deficient A549 ρ0 cells. We show that bleomycin caused more mtDNA than nDNA damage. Furthermore, there is activation of caspase-3, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), and PKD1, translocation of Bax, decrease in MMP, and finally apoptosis. However, in the mtDNA-depleted A549 ρ0 cells, there was no activation of caspase-3 or cleavage of PARP and PKD1, and, most importantly, A549 ρ0 cells were highly resistant to bleomycin-induced apoptosis. These data suggest that bleomycin-induced toxicity may occur in part as a result of mtDNA damage, which leads to apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells, and that, conversely, in the presence of mtDNA depletion, bleomycin-mediated apoptosis is significantly reduced.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Electrophoretic-grade reagents NaCl, sodium deoxycholate, SDS, Tween 20, Tris, and nonfat dry milk powder were obtained from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA); nitrocellulose membranes from Amersham Bioscience (Piscataway, NJ); antibody to PKD1 from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); Bax, actin, Cox4, and mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 (mtHsp70, GRP75, H-155) antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); caspase-3 monoclonal antibody from BioVision (Mountain View, CA); and PARP antibody from BD Bioscience (Palo Alto, CA). The electrochemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting kit, including horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, was obtained from Amersham Bioscience. Unless otherwise stated, cell culture reagents were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), and all biochemical reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Measurement of ROS.

Generation of ROS in response to bleomycin in A549 cells was measured by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR). EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker EMX EPR spectrometer (Billerica, MA) operating at 9.81 GHz with a modulation frequency of 100 kHz and equipped with an ER 4122 super-high Q cavity. All experiments were performed at room temperature. For these experiments, cells were washed and maintained in HBSS. The spin trap 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) was added to the medium 5 min before bleomycin to allow DMPO to penetrate the cells. After 15 min of incubation at 37°C, a sample of the culture medium was collected and transferred to a quartz flat cell.

Electron microscopy.

For the ultrastructural analysis, A549 and A549 ρ0 cells were washed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and fixed in a modified Karnovsky's buffer (2.0% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4). They were postfixed with 2% OsO4 in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 1.5 h at room temperature. The samples were washed briefly in distilled H2O, dehydrated by a graded ethanol series, infiltrated using propylene oxide and Epon epoxy resin, and finally embedded in epoxy resin. Thin sections were cut using an ultramicrotome (Ultracut UCT, Leica, Deerfield, IL) and collected on copper grids. The sections were examined for mitochondria and other organelles under a transmission electron microscope (Techni 12) at 80 kV, images were collected with a digital camera (Soft Imaging System Megaview III), and figures were assembled in Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

Cell culture.

A549 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1× antibiotic-antimycotic mixture and 10% FBS (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) and maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2-95% air. A549 ρ0 cells were derived from A549 cells as previously described (7) by culturing in the presence of EtBr (50 ng/ml), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and uridine (100 μg/ml) in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS for >20 generations. The control parental A549 cells were maintained for the same period in normal culture medium. Establishment of the A549 ρ0 cell line was confirmed by PCR (see Fig. 2, B and C) using gene-specific primers (see Table 2). Expression of cytochrome oxidase (COX) was used to confirm loss of mtDNA. The three subunits of the COX complex (COX-1, -2, and -3) in the mitochondrial electron transfer system are encoded by mtDNA (the other 10 are encoded by nDNA). Nonamplification of the COX complex (COX-1, -2, and -3) in ρ0 cells by PCR is an indication that the cells are devoid of functionally intact DNA (see Fig. 2B). On the other hand, actin (encoded by nDNA) is normally expressed in ρ0 cells. In addition, other cell lines used for related studies, including HepG2, 293, and DU145, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and grown under conditions recommended by the supplier.

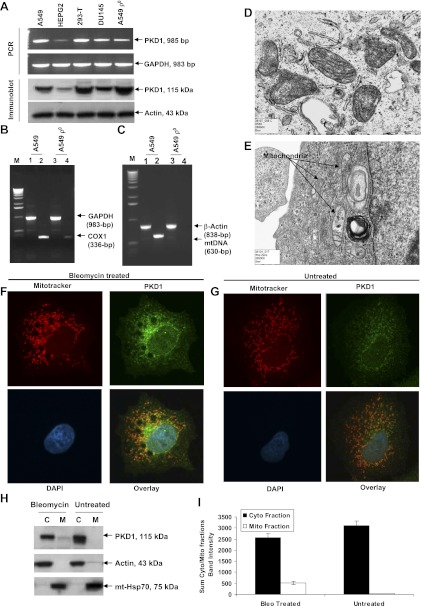

Fig. 2.

Effect of bleomycin on PKD1 expression. A: PCR (top) and Western blot (bottom) analysis of PKD1 expression in A549, HepG2, 293, and DU145 cells. For PCR amplification, mRNA from different human cell lines was isolated, transcribed to cDNA, and subjected to PCR analysis. For immunoblot analysis, exponentially growing cells were lysed in SDS-PAGE buffer and subjected to immunoblotting, and endogenous PKD1 was detected with anti-PKD1 antibody (1:1,000 dilution). A representative PCR amplification and a Western blot of 3 independent experiments are shown. B and C: confirmation of A549 ρ0 cell line. Total RNAs were isolated from A549 and A549 ρ0 cells, and mRNA levels of cytochrome oxidase (COX)-1 and GAPDH were determined by RT-PCR. B: expression of mtDNA-encoded subunit of COX-1 was normal in A549 cells and barely detectable in A549 ρ0 cells. C: mtDNA content in A549 and A549 ρ0 cells. Total cellular DNA was extracted from both cell lines using the Qiagen Genomic DNA kit, and mtDNA and β-actin nDNA were amplified by PCR. mtDNA was not amplified from genomic DNAs of ethidium bromide (EtBr)-treated (ρ0) cells. On the other hand, the β-actin gene, a nDNA control, was amplified in control and EtBr-treated cells. This observation demonstrated that the EtBr-treated A549 cells were entirely devoid of mtDNA (ρ0 cells). M, molecular weight marker. D and E: ultrastructural morphology of mitochondria. D: A549 cells show mitochondria with complete cristae. E: A549 ρ0 cells reveal swollen, irregular-shaped mitochondria and mitochondria with incomplete cristae. F and G: colocalization of PKD1 to mitochondria in A549 cells. Cells were stained with PKD1 (green), MitoTracker Red CMXRos dye (red), and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). Note colocalization of PKD1 in mitochondria in bleomycin-treated cells (F) and markedly less colocalization of PKD1 in control (untreated) cells (G). H: confirmation that PKD1 was localized to mitochondria. Cytosolic (C) and mitochondrial (M) fractions from untreated and bleomycin-treated A549 cells were subjected to immunoblotting, and PKD1 was detected with anti-PKD1 antibody. Actin and mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 (mtHsp70) were used as loading controls. I: densitometry results of the 115-kDa PKD1 cytosolic (Cyto) and mitochondrial (Mito) bands from gels in H. Values are means ± SE of 3 independent experiments. Bleomycin (Bleo) treatment caused a highly significant increase in the fraction localized to mitochondria (P < 0.009 for interaction of treatment with subcellular fractions, by 2-factor ANOVA).

Table 2.

Primer pairs to confirm establishment of A549 ρ0 cell line

| Gene | Primer Pairs | Product Size, bp |

|---|---|---|

| Human mtDNA | 630 | |

| 1 | 5′ CCT AGG GAT AAC AGC GCA AT 3′ | |

| 2 | 5′ TAG AAG AGC GAT GGT GAG AG 3′ | |

| COX-1 | 336 | |

| Forward | 5′ ACA CGA GCA TAT TTC ACC TCC G 3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′ GGA TTT TGG CGT AGG TTT GGT C 3′ |

mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; COX, cytochrome oxidase.

Genotoxin treatment.

A549 cells were counted and seeded on 60-mm2 tissue culture dishes at 8 × 104 cells/ml and maintained in the presence or absence of 100 μM bleomycin. In related studies, other cytotoxic agents, such as 1-β-d-arabinofuranosylcytosine (ara-C, 100 μM), cisplatin (100 μM), and doxorubicin (40 μM), were used for comparison. At 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h, cells were harvested for assessment of nDNA and mtDNA damage by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and for protein expression by Western blotting.

qPCR for mtDNA and nDNA.

qPCR was performed as described elsewhere (15, 34, 40). Briefly, genomic DNA was purified using the Genomic-tip and Genomic DNA buffer set kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Purified DNA and PCR products were quantified by PicoGreen dye (Molecular Probes/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and read on a fluorescence plate reader (model FL600, Bio-Tek) with 485-nm excitation and 535-nm emission. λ DNA/HindIII (Invitrogen) was used to generate a standard curve. PCR was performed using the GeneAmp XL PCR Kit (Roche, Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, NJ) on a thermocycler (T Gradient, Biometra, Goettingen, Germany). Primers and conditions used to amplify mtDNA and genomic DNA are described elsewhere (34). All qPCR analyses were carried out in triplicate (i.e., 3 qPCRs per primer combination per sample), and the values were averaged. All biological experiments were repeated three times.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was harvested from the A549, HepG2, 293, DU145, and A549 ρ0 cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using random hexamer (Roche Applied Biosystems) and SuperScript II RNase H Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen), and PCR was performed using gene-specific primers (Table 1). For RT-PCR on PKD1 expression, cells were grown and treated with bleomycin and cDNA was synthesized. Primer sequence and product size for PKD1 are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer pairs for RT-PCR to determine PKD1 transcript levels

| Gene | Primer Pairs | Product Size, bp |

|---|---|---|

| PKD | 985 | |

| Forward | 5′ ACG GCA CTA TTG GAG ATT GG 3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′ CAG ACC ACA TGT CTA GAG AGC GAT TG 3′ | |

| GAPDH | 983 | |

| Forward | 5′ TGA AGG TCG GAG TCA ACG GAT TTG GT 3′ | |

| Reverse | 5′ CAT GTG GCC ATG AGG TCC ACC AC 3′ |

Immunoblot analysis.

A549 cells were grown and treated with bleomycin as described above. Cell lysates (60–70 μg) were separated on 4–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Primary antibodies against PKD1, caspase-3, PARP, Bax, and Cox4 were used at 1:1,000 dilution with overnight incubation at 4°C and the species-specific secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoblots were detected by ECL. Cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions used in immunoblot analysis were prepared as described previously (16). Bands in the immunoblots were quantified using the Alpha Innotech system and software (San Leandro, CA).

Isolation of mitochondria.

Cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were prepared as described previously (16). Briefly, cells were collected and washed twice with cold PBS. The cells were lysed in cold hypotonic buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 0.015% digitonin), kept on ice for 3 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected as the cytoplasmic fraction. Insoluble fractions were further extracted with ice-cold 0.5% Triton X-100 in hypotonic buffer for 1 min on ice. Subsequently, cellular debris was pelleted, and the supernatant was collected as the mitochondrial fraction. Cytoplasmic and mitochondrial fractions were stored at −80°C. mtHsp70 was used as a loading control for the mitochondrial fraction and detected with GRP75 (H-155) antibody (catalog no. sc-13967, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Determination of cell death and apoptosis by annexin V.

Apoptosis was measured using the annexin V assay kit (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, A549 cells were collected at various time points, washed with PBS, and resuspended in 1× binding buffer at 0.5 × 106 cells/ml. The 100-μl cell suspension was incubated with 3 μl of annexin V-FITC (1 μg/ml) and 10 μl of propidium iodide (PI, 2.5 μg/ml) for 15 min in the dark. After addition of 400 μl of 1× binding buffer to each sample, analysis was carried out using a FACSort (Becton Dickinson) within 1 h. Annexin+/PI+ cells were defined as necrotic, while annexin+/PI− cells were defined as apoptotic. Identical instrument settings were used for the parent and mtDNA-depleted cells. Because of the presence of EtBr in mtDNA-depleted A549 ρ0 cells, an increase in the longer-wavelength detection channels was observed; thus setting of the analysis gates was based on the control cells for each individual cell line.

Analysis of caspase activity by flow cytometry.

Caspase activity was determined using the CaspaTag caspase-3/7 assay kit (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 300 μl of cells at an initial concentration of 5 × 105 cells/ml were added to 10 μl of a 30× working stock of CaspaTag reagent. Cells were incubated at 37°C in 7% CO2 for 60 min, washed in 2 ml of CaspaTag wash buffer, and resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS. Immediately prior to flow cytometric examination, PI was added to each sample at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Cells (1 × 105) were analyzed using a FACSort flow cytometer with an excitation of 488 nm and emission of 530 and 585 nm for caspase activity and PI fluorescence, respectively. Only PI− cells were analyzed for caspase activity.

Immunocytochemical localization of PKD1.

A549 cells grown on coverslips (2-chamber slides, Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) were treated with bleomycin (100 μM) for 48 h. Cells were washed once with PBS and incubated in phenol red-free medium with 50 nM MitoTracker Red CMXRos dye (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 min in a tissue culture incubator at 37°C. Cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4.0% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. Cells were washed as described above, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min, and washed again three times with PBS. Cells were blocked in blocking buffer (5% normal donkey serum, 2% BSA, 0.1% fish skin gelatin, and 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature and then stained for 60 min at 25°C with anti-PKD1 antibody diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer. After extensive washing of the cells with PBS, binding of antibodies to PKD1 was detected by incubation for 60 min at 25°C with fluorophore-labeled donkey anti-rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes) diluted 1:250 in 5% BSA-PBS. After they were washed with PBS, the slides were air-dried, and coverslips were mounted using ProLong Gold antifade reagent with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Molecular Probes) and viewed using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (model LSM 510) mounted on an Axiovert 200M microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Measurement of ATP level in A549 cells.

ATP level in bleomycin-treated A549 cells was measured by ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit HS II (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, A549 cells were lysed in 250 μl of lysis reagent for 5 min at room temperature and spun at 10,000 g for 60 s, and supernatant was collected. Supernatant was diluted 1:1 in dilution buffer, and the reaction was initiated by addition of 100 μl of luciferase reagent in a black microtiter plate in a total volume of 200 μl. ATP standards were made by serial dilution at 10−4–10−12 mol of ATP. Data were collected by reading the 96-well plate on a microplate luminometer at 562 nm.

DNA analysis by flow cytometry.

The DNA content for each sample was determined by flow cytometry by pelleting 3–5 ml of cells from control and treated samples. The cells were fixed by the slow addition of cold 70% ethanol to a volume of ∼1.5 ml, adjusted to 5 ml with cold 70% ethanol, and stored at 4°C overnight. For flow analysis, the fixed cells were pelleted, washed once in PBS, and stained in 1 ml of PI (20 μg/ml) and 1,000 U of RNase ONE (Promega, Madison, WI) in 1× PBS for 20 min. Cells (7.5 × 104) were analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSort by gating on a PI area vs. width dot plot to exclude cell debris and cell aggregates. The percentage of degraded DNA was determined by the number of cells with subdiploid DNA divided by the total number of cells examined under each experimental condition in the gated region.

Statistical analysis.

All assays/experiments were performed on multiple occasions with triplicate samples (i.e., 3 experiments carried out at separate times) unless otherwise indicated. Values are means ± SE of replicate determinations. qPCR data were analyzed by ANOVA followed, when appropriate, by Fisher's protected least significant difference (PLSD) post hoc test, and these data are graphed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Effect of bleomycin on ROS level in A549 cells.

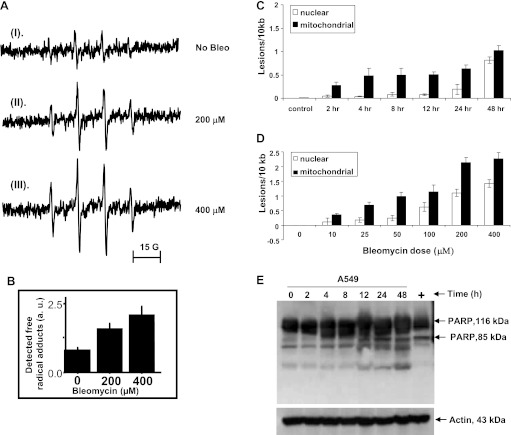

The effect of bleomycin on DMPO/.OH adduct formation was evaluated by EPR (Fig. 1A). O2− and .OH are too reactive and, therefore, short-lived to be directly detected. Nevertheless, both species can be trapped by the spin-trapping agent DMPO, producing EPR-detectable radical adducts. DMPO/.OOH adduct decays in a zero-order process to DMPO/.OH. Therefore, the production of DMPO/.OH directly measured by EPR was used as an index of ROS (O2− and .OH) production. In the absence of bleomycin, EPR signals were barely detectable (Fig. 1A, I). In the presence of bleomycin, the DMPO/.OH EPR signal was evident, and its intensity was directly proportional to the concentration of bleomycin (Fig. 1, A and B). Thus bleomycin exposure resulted in a dose-responsive increase in ROS.

Fig. 1.

A and B: measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR). Bleomycin exposure resulted in a dose-responsive increase in ROS. au, arbitrary units. C and D: effect of bleomycin on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and nuclear DNA (nDNA). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was used to determine mtDNA and nDNA damage in A549 cells. Total DNA was isolated and subjected to qPCR analysis. A549 cells were treated with 100 μM bleomycin for 0–48 h (C) and 0–400 μM bleomycin for 48 h (D), and mtDNA and nDNA damage was assessed. Bleomycin caused more mtDNA than nDNA damage in time-course (C) and dose-response (D) experiments (P < 0.0001 in both cases). Values are means ± SE from 4 different experiments. E: cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in bleomycin-treated cells. Expression of PARP in cultured A549 and A549 ρ0 cells was identified by immunoblot analysis. Both cell lines were treated with bleomycin for 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h, and cells were lysed directly in lysis buffer. For positive control, cells were treated with doxorubicin (10 μM, 12 h). Membranes were incubated with anti-PARP (1:1,000 dilution). An 85-kDa active fragment of PARP was detected in A549 cells starting at 12 h. There was no cleavage of PARP in A549 ρ0 cells (data not shown). A representative Western blot of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Bleomycin caused more mtDNA than nDNA damage.

Bleomycin is reported to cause DNA damage by release of ROS (13, 22, 23, 30). Using a highly sensitive qPCR assay (34), we assessed mtDNA and nDNA damage in A549 cells after 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h of bleomycin treatment (Fig. 1C). Initial three-factor (treatment, genome, and time points) ANOVA showed that the treatment caused concentration-dependent DNA damage (P < 0.0001 for main effect of treatment), with more mtDNA than nDNA across treatment and time points (P < 0.0001 for main effect of genome). Damage to mtDNA and nDNA increased with time (P < 0.0001 for main effect of time point). The greater sensitivity of mtDNA was statistically significant at all time points except 0 and 48 h (P = 0.016 for time point × genome interaction; P < 0.05 cutoff for Fisher's PLSD post hoc analysis of genome differences at each time point). A dose (0–400 μM)-response analysis of bleomycin's effect at 48 h also revealed more mtDNA than nDNA damage (P < 0.0001 for main effect of genome; Fig. 1D). In response to significant damage to mtDNA and nDNA, we looked at activity of PARP, an important marker associated with DNA damage, in bleomycin-treated cells. Bleomycin treatment resulted in cleavage of the 116-kDa PARP starting at 12 h after bleomycin with generation of an 85-kDa fragment continuing up to 48 h (Fig. 1E). This time frame of PARP cleavage coincides with the timing of mtDNA and nDNA damage.

PKD1 expression.

Since there were no available data on PKD1 expression in A549 cells, we determined PKD1 levels in A549 cells and compared the expression levels in standard well-characterized cell lines by PCR and Western blot analysis. We observed a high constitutive expression of PKD1 in A549 and other cell lines, except HepG2 cells, in which mRNA and protein expression of PKD1 was considerably lower. The highest steady-state levels were detected in kidney (293-T) and lung (A549) cell lines (Fig. 2A), suggesting a cell-type or organ-specific expression of PKD1. Immunoblot analysis of PKD1 shows a double band in 293-T and DU145 cell lines. This is well described by Haworth et al. (12). Possible explanations for these doublets are as follows: 1) differential splicing of a single gene or 2) posttranslational modification/protein maturation process other than phosphorylation. Additionally, the A549 ρ0 cell line showed a slightly lower level of mRNA and protein expression than the parent A549 cell line. Establishment of the A549 ρ0 cell line was confirmed by PCR (Fig. 2, B and C). GAPDH was amplified as a PCR control and β-actin as a loading control for Western blot analysis. The morphological association of PKD1 with mitochondria was analyzed using confocal laser scanning microscopy. PKD1 shows a broad speckled distribution throughout the cytosolic region of the A549 cells (Fig. 2F). Colocalization of PKD1 and MitoTracker Red dye shows that PKD1 is localized within mitochondria in A549 cells after bleomycin treatment (Fig. 2F) and is slightly more prominent than in the bleomycin control (Fig. 2G). However, to biochemically confirm the mitochondrial localization of PKD1 after bleomycin treatment, A549 cells were fractionated into cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions. The results (Fig. 2H) confirm that PKD1 is mostly cytosolic, but in response to bleomycin, a fraction is localized to mitochondria. Much more PKD1 was present in the cytosolic than the mitochondrial fraction under all conditions (P < 0.0001 for main effect of cellular fraction, by 2-factor ANOVA), but bleomycin treatment caused a highly significant increase in the fraction localized to mitochondria (P = 0.009 for interaction term) with no change in the overall amount of PKD1 detected (P = 0.83 for main effect of treatment; Fig. 2I). PKD1 bands in Fig. 2H were quantified and are represented in Fig. 2I. It is possible that the amount of PKD1 might actually be higher, but the recovery is low in the mitochondrial fraction because of its possible loss during mitochondrial isolation, as seen with some other outer membrane mitochondrial proteins such as Nkin2 (10). The contamination of the two fractions as judged by the specific markers, actin for the cytosolic fraction and mtHsp70 for the mitochondrial fraction, was very low.

Ultrastructural morphology.

A549 cells contained normal mitochondria with an electron-dense matrix and regular cristae structure (Fig. 2D), whereas A549 ρ0 cells contained evidence of largely swollen and distorted mitochondria with translucent matrix. Also the morphology of cristae was markedly varied, short, and circular (Fig. 2E).

Bleomycin did not cause PKD1 phosphorylation.

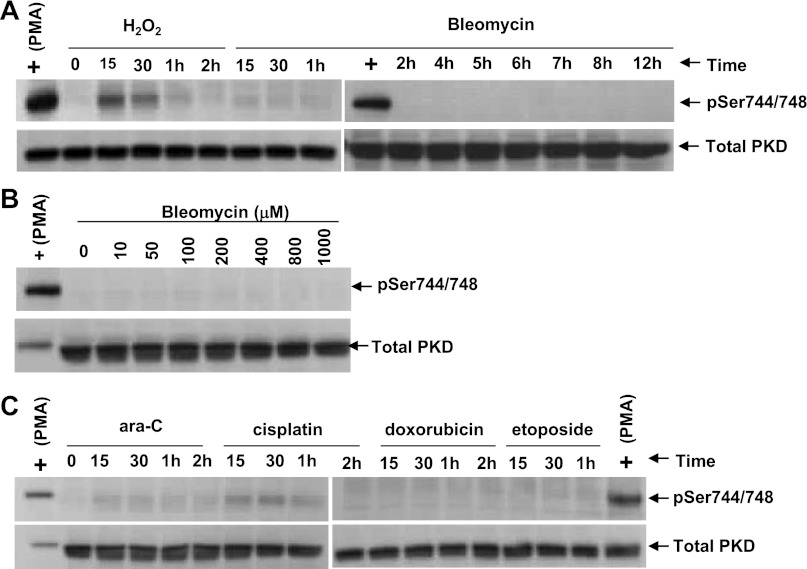

PKD1 is activated by phosphorylation at multiple sites; however, it is the phosphorylation at Ser744/748 (both in the activation loop) that is critical in the activation of PKD1 (32, 44). Thus we determined if bleomycin induces phosphorylation at Ser744/748. PMA and H2O2 were positive controls, and both induced phosphorylation of PKD1 at Ser744/748 in A549 cells (Fig. 3A). However, bleomycin did not phosphorylate Ser744/448 as a function of time or concentration in the A549 cells (Fig. 3, A and B). Bleomycin, even at 1,000 μM, did not phosphorylate Ser744/748 (Fig. 3B). Other genotoxic agents such as ara-C, cisplatin, doxorubicin, and etoposide also did not phosphorylate Ser744/748 under similar experimental conditions (Fig. 3C), suggesting that bleomycin and other genotoxic agents might activate PKD1 through an alternative pathway, such as caspase-3-mediated activation.

Fig. 3.

Effect of bleomycin and other agents on PKD1 phosphorylation. A: PMA and H2O2, but not bleomycin, induce phosphorylation of PKD1 in A549 cells. A549 cells were treated with PMA (0.1 μM), H2O2 (1 mM), and bleomycin (100 μM) for various times (15 and 30 min and 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 12 h). Cells were lysed in SDS-PAGE sample buffer and analyzed by Western blot to detect PKD1 activation loop phosphorylation using phosphospecific (pSer744/748) antibody. B: bleomycin dose response. A549 cells were treated with 0–1,000 μM bleomycin for 15 min. Cells were scraped in SDS-PAGE buffer and subjected to immunoblot using phosphospecific antibody. Even 1,000 μM bleomycin failed to induce Ser744/748 phosphorylation. C: various apoptosis-inducing agents did not phosphorylate PKD1 in the activation loop. A549 cells were treated with 1-β-d-arabinofuranosylcytosine (ara-C, 100 μM), cisplatin (100 μM), doxorubicin (40 μM), and etoposide (50 μM) for various times. Cells were lysed, and immunoblot analysis of the lysates was performed with phosphospecific (pSer744/748) antibody. Immunoblots were stripped and reprobed against total PKD1 protein.

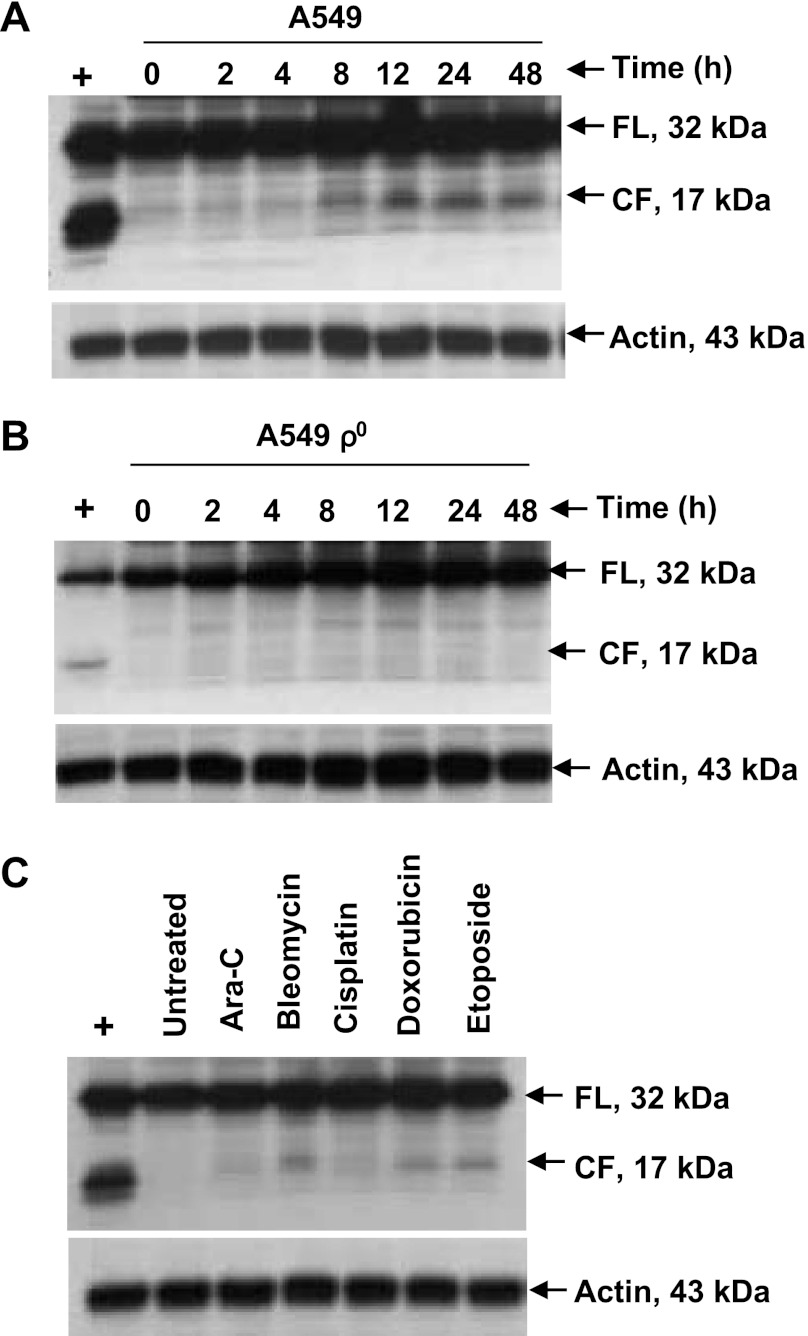

Bleomycin causes caspase-3 activation in A549 cells, but not A549 ρ0 cells.

Since bleomycin did not activate PKD1 by phosphorylation, we next examined the alternate caspase-3-mediated pathway of activation. We used A549 and the mtDNA-depleted A549 ρ0 cells to determine caspase-3 activation. Western blot analysis of A549 cells demonstrated that bleomycin treatment induced cleavage of caspase-3 starting at 8–12 h to generate the 17-kDa active fragment (Fig. 4A). However, no such activation of caspase-3 was seen in A549 ρ0 cells under similar experimental conditions (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, doxorubicin and etoposide treatment of A549 cells resulted in a caspase-3 17-kDa cleaved active fragment similar to that observed with bleomycin, whereas caspase-3 cleavage was less prominent with ara-C and cisplatin (Fig. 4C). Thus caspase-3 activation was present in A549 cells, but not in A549 ρ0 cells.

Fig. 4.

Proteolytic cleavage of caspase-3 in A549 and A549 ρ0 cells by various apoptosis-inducing agents. A and B: A549 and A549 ρ0 cells were treated with 100 μM bleomycin for 0–48 h, and lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-caspase-3 antibody (1:1,000 dilution). Exposure to 0.5 μM staurosporine (positive control) for 6 h induced enzymatically active 17-kDa fragment of caspase-3. Caspase-3 was activated by 12 h in A549 cells; however, no caspase-3 activation was observed in A549 ρ0 cells over the 48-h period. C: A549 cells were treated with ara-C (100 μM), bleomycin (100 μM), cisplatin (100 μM), doxorubicin (40 μM), and etoposide (50 μM) for 12 h, and lysates were subjected to immunoblot. Bleomycin, doxorubicin, and etoposide resulted in caspase-3 17-kDa cleaved active fragment, whereas cleavage was less prominent for ara-C and cisplatin. A representative immunoblot of 3 independent experiments is shown. FL, full length; CF, cleaved fragment.

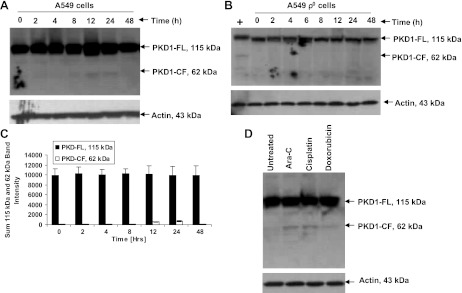

Bleomycin causes PKD1 cleavage in A549 cells, but not in A549 ρ0 cells.

To determine if activation of caspase-3 resulted in PKD1 activation by its cleavage to the 62-kDa fragment, which sensitizes cells to apoptosis, we treated A549 and A549 ρ0 cells with bleomycin and harvested cells at various time points. Immunoblot analysis of the lysates with an anti-PKD1 antibody showed a time-dependent cleavage of PKD1 in A549 cells into its 62-kDa cleaved fragment (Fig. 5A) starting at 12 h (P < 0.0001 for effect of time on levels of the cleaved band, by 1-factor ANOVA), and this effect was significant only at 12 and 24 h (P < 0.0001 for 12 and 24 h compared with all other times, P > 0.05 for all other comparisons except 12 vs. 24 h, P = 0.05, by Fisher's PLSD post hoc test; Fig. 5B). However, no cleaved catalytically active fragment of PKD1 was seen in A549 ρ0 cells under similar experimental conditions (Fig. 5C). Other DNA-damaging agents, including ara-C, cisplatin, and doxorubicin, also cleaved PKD1, generating the 62-kDa cleaved fragment (Fig. 5D). The kinetics of cleavage of PKD1 in A549 cells coincided with the activation of caspase-3.

Fig. 5.

Proteolytic cleavage of PKD1 by various genotoxic agents. A and B: proteolytic cleavage of PKD1 in cultured A549 and A549 ρ0 cells. Cells were treated with 100 μM bleomycin for 0–48 h. Resolved proteins were detected by immunoblotting using antigen-specific antibody. Cleaved (62-kDa) PKD1 fragment (PKD1-CF) was detected starting at 12 h posttreatment in A549 cells but was not detected in A549 ρ0 cells. PKD1-FL, full-length (115-kDa) PKD1 fragment. C: densitometry results of the 115- and 62-kDa bands in A. Values are means ± SE of 3 independent experiments. P < 0.0001 for amount of cleaved fragment at 12 and 24 h compared with all other times. Positive control in B is cellular extract from A549 cells that were treated with 100 μM bleomycin for 12 h. D: A549 cells were untreated or treated with ara-C (10 μM), cisplatin (100 μM), and doxorubicin (40 μM) and harvested after 12 h. Protein fractions were subjected to immunoblot and analyzed with anti-PKD1 antibody. Cleaved (62-kDa) PKD1 fragment was detected starting at 12 h posttreatment. Representative immunoblot from ≥3 independent experiments is shown.

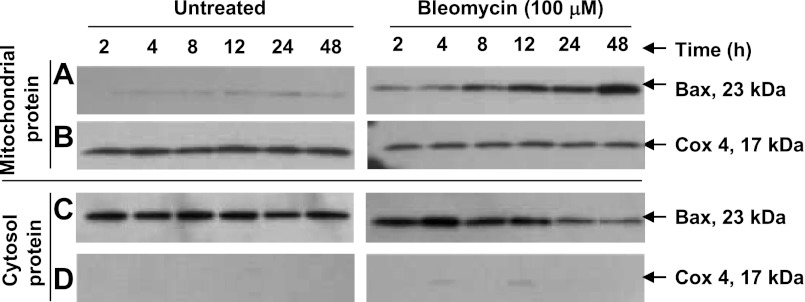

Bleomycin exposure causes mitochondrial localization of Bax.

Bax is associated with mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and is often required for the release of the mitochondrial intermembrane proteins and the induction of apoptosis. To assess the role of Bax in bleomycin injury, we studied Bax activation (translocation from cytosol to mitochondria) from 2 to 48 h in A549 cells. Bleomycin caused translocation of Bax that was time-dependent, revealing a progressive increase over 48 h (Fig. 6) and further supporting the role of the mitochondrial pathways in mediating apoptosis.

Fig. 6.

Translocation of Bax. Expression of Bax in A549 cells was identified by immunoblot analysis. After treatment of A549 cells with 100 μM bleomycin for 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h, cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were obtained. Proteins were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and immunoblot was analyzed using anti-Bax antibody; equal gel loading was confirmed by detection of Cox4 on the same blots. Translocation of Bax is time-dependent following bleomycin treatment and progressively increases over 48 h (A). A representative immunoblot of 3 independent experiments is shown.

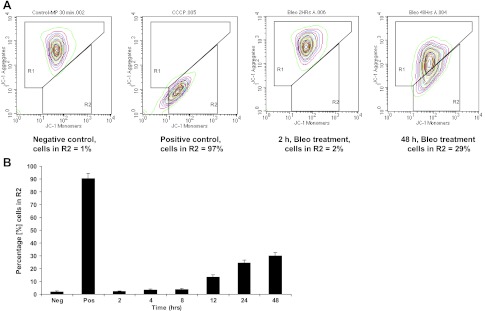

Bleomycin decreases MMP and ATP levels.

MMP is an important indicator of mitochondrial function. To test whether the high levels of mtDNA damage were associated with mitochondrial loss of function, we measured MMP and ATP levels after bleomycin exposure. The mitochondria-specific cationic dye JC-1 undergoes potential-dependent accumulation in mitochondria and is used to measure changes in MMP. There was a significant decrease in MMP at 48 h after bleomycin treatment, with ∼30% of the cells having a reduced aggregate fluorescence compared with nontreated cells (Fig. 7). A change in MMP can affect ATP generation, ultimately leading to transition pore opening, cytochrome c release, and apoptosis (21). Bleomycin also significantly decreased ATP level at 48 h compared with control (P ≤ 0.001; data not shown).

Fig. 7.

A: mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was measured by JC-1 dye. Cationic JC-1 dye exhibits potential-dependent accumulation in mitochondria, indicated by a fluorescence emission shift from green (530 nm) to red (575 nm). In healthy cells, the dye enters the mitochondria, forms aggregates, and stains the mitochondria bright red and is detectable at 575 nm (R1 zone). In apoptotic cells, the dye stays in the cytoplasm as a monomer and fluoresces green and is detectable at 530 nm (R2 zone). At 48 h after bleomycin treatment, ∼30% of the cells have lost aggregate fluorescence compared with nontreated cells. Cells were exposed to the MMP disrupter carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP, 50 μM) for 5 min as a positive control. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Results for only 2 and 48 h are shown. B: graphic representation of A549 cells in the R2 zone after 2–48 h of bleomycin treatment.

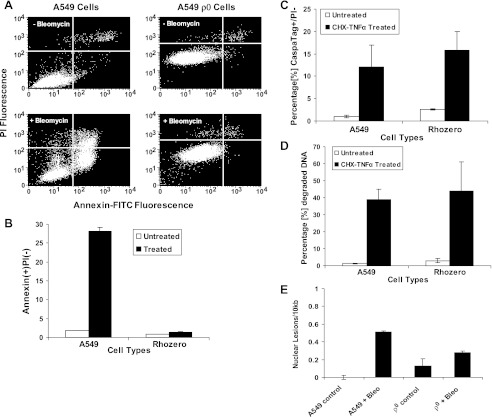

A549 ρ0 cells are more resistant to bleomycin-induced apoptosis than A549 cells.

Since bleomycin damages mtDNA and is associated with activation of the mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathways, we directly compared the susceptibility of the parent A549 cells with that of the A549 ρ0 cells to bleomycin toxicity. Annexin V+/PI− stain was used to analyze A549 and A549 ρ0 cells for cell death: 28 ± 1% of A549 cells were annexin V+/PI− compared with only 2 ± 0.2% of A549 ρ0 cells (P < 0.001), indicating that the A549 ρ0 cells were resistant to bleomycin toxicity (Fig. 8, A and B). To rule out the possibility that A549 ρ0 cells were immune to apoptosis because of their altered mitochondria, A549 and A549 ρ0 cells were treated with cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) and TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 18 h and analyzed for caspase activity and DNA degradation by CaspaTag and PI assay, respectively. As shown in Fig. 8, C and D, A549 and A549 ρ0 cells undergo apoptosis when treated with cycloheximide and TNF-α. Also there was no statistical difference in the level of apoptosis between these two cell lines as seen by CaspaTag assay (A549 and A549 ρ0 treated, P = 0.70) and DNA degradation assay (A549 and A549 ρ0 treated, P = 0.70). To assess if bleomycin affected nDNA similarly in A549 and A549 ρ0 cells, nearly confluent A549 and A549 ρ0 cells were treated with 100 μM bleomcyin for 48 h, and genomic DNA was analyzed by qPCR (Fig. 8E). Bleomycin exposure resulted in similar levels of nDNA damage in both cell lines, although there was a statistically greater degree of nDNA damage in the A549 cells (P = 0.004 for interaction term, by 2-factor ANOVA on cell type and dose). The small difference in nDNA damage after bleomycin exposure in these two cell lines (Fig. 8E) suggests that the marked resistance to apoptosis by A549 ρ0 cells (Fig. 8E) was related to the absence of mitochondria, and not to a differential susceptibility to nDNA damage.

Fig. 8.

Evaluation of cell death using the annexin V assay. A: A549 and A549 ρ0 cells were plated at 5 × 105 cells/well and grown for 48 h. At 48 h after bleomycin (100 μM) treatment, cell death was measured using annexin V assay and compared with respective vehicle controls. PI, propidium iodide. B: cell death in A549 and A549 ρ0 cells. At 48 h after bleomycin treatment, 28 ± 1% of A549 cells were annexin+/PI− compared with only 2 ± 0.2% of A549 ρ0 cells (P < 0.001). C and D: apoptosis in A549 and A549 ρ0 cells. A549 and A549 ρ0 cells at 80% confluence were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) and TNF-α or vehicle control to confirm functional presence of caspases and apoptotic nucleases, respectively. Both cell types were analyzed for apoptosis by the CaspaTag assay 18 h after treatment and showed an indistinguishable rate of apoptosis (P = 0.70). Both cell types were analyzed for DNA degradation 18 h after treatment, and the rate of DNA degradation was indistinguishable (P = 0.70). Data are from 3 separate biological experiments, with triplicate measurements made in both experiments. E: quantification of genomic DNA damage in A549 and A549 ρ0 cells by qPCR. A549 and A549 ρ0 cells were treated with 100 μM bleomycin for 48 h and assessed for nDNA damage. Values are means ± SE from 3 different experiments.

DISCUSSION

Oxidative stress plays a key role in the pathogenesis of many inflammatory lung diseases (31). Bleomycin is an antitumor agent that, in clinical use, produces pulmonary injury, leading to severe progressive pulmonary fibrosis in 1–2% of patients. Although many of the morphological and physiological changes associated with bleomycin pulmonary toxicity are well characterized, the underlying responses within lung cells that undergo injury are not well understood. Our study shows that bleomycin in lung cells significantly damages mtDNA compared with nDNA and triggers a variety of mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathways. Furthermore, mtDNA-depleted lung cells are resistant to bleomycin-induced apoptosis, suggesting a potentially central role of mitochondrial damage in the pathogenesis of bleomycin-mediated acute lung injury.

Using a qPCR assay (34) that permits unbiased comparison of mtDNA and nDNA damage, we found that bleomycin produced more damage in the mitochondrial than nuclear genome. Since bleomycin is expected to cause DNA damage by oxidative mechanisms, these results are consistent with previous observations of greater mtDNA than nDNA damage after exposure to prooxidants (33, 50). Damage to mtDNA can trigger the intrinsic (mitochondrial) apoptotic pathway, and using four different markers for induction of apoptosis, including PARP, caspase-3, Bax, and MMP, we found that apoptosis was induced by bleomycin. These four apoptotic markers are interconnected and associated with mitochondrial apoptotic pathways. For example, PARP, a 116-kDa nuclear protein, is a well-characterized substrate for caspase-3. Activated caspase-3 cleaves PARP, generating 89- and 24-kDa inactive fragments and causing apoptosis (18). Bax in apoptotic cells undergoes conformational changes to form oligomers and permeabilize the outer mitochondrial membrane, resulting in the release of proapoptotic factors (1). Changes in MMP results in the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytoplasm. In the cytosol, cytochrome c activates caspase-9, and activated caspase-9 cleaves and activates executioner caspase-3. In response to bleomycin treatment, all four pathways were activated in A549 cells. The use of A549 ρ0 cells in our studies demonstrated that there was no activation of caspase-3 or cleavage of PARP (data not shown) and PKD1 as measures of mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathways. Furthermore, activation of PKD1 is thought to act as an oxidant sensor within mitochondria that is key to mitochondrion-to-nucleus signaling. PKD1 is cleaved by caspase-3 at the CQND378S site in response to genotoxic stress, attains an active state, and can sensitize cells to DNA damage-induced apoptosis (9). Another oxidant-based mechanism to activate PKD1 is phospholipase C-PKC-mediated phosphorylation of PKD1 at Ser744/748 (43, 45). In our study, bleomycin and other genotoxic agents such as ara-C, cisplatin, doxorubicin, and etoposide activated caspase-3, which activates PKD1 and leads to apoptosis. In addition, bleomycin and these agents are known to induce DNA damage, cleave PKD1, and induce apoptosis (9, 42). However, none of these agents, including bleomycin (Fig. 3B), induced phosphorylation at Ser744/748 in A549 cells in our study. However, PMA and H2O2, as positive controls (44), induced PKD1 phosphorylation at Ser744/748 within 15 min (Fig. 3A). Taken together, these data suggest that genotoxic agents that induce DNA damage preferentially activate PKD1 through a caspase-3-dependent pathway, apparently overriding expression of antiapoptotic genes, which are activated via NF-κB (39).

The A549 ρ0 cells generated in our laboratory demonstrated depletion of mtDNA, as evidenced by absence of detection of the COX-1 gene by PCR (Fig. 2B). The mitochondrial morphology in A549 ρ0 cells was swollen, with irregular cristae (Fig. 2E) and low MMP (data not shown), which is consistent with other established mtDNA-deficient cell lines, such as ρ-L929 and ρ-143B cells (24), L-cells (25), and ρ SH-SY5Y cells (36) Interestingly, there was no cleavage or activation of caspase-3 (Fig. 4B), PKD1 (Fig. 5B), and PARP (data not shown) in the A549 ρ0 cells up to 48 h after bleomycin treatment. Most importantly, there was no evidence of significant bleomycin-induced apoptosis in the A549 ρ0 cells compared with the parental A549 cells (Fig. 8). Since there was only a minimal difference in nDNA damage after bleomycin in A549 ρ0 cells vs. A549 cells (Fig. 8E), the lack of apoptosis in the A549 ρ0 cells during bleomycin treatment is likely attributable to depletion of mtDNA, and not depletion of nDNA or nDNA damage. In support of this, the apoptotic machinery was intact in the A549 ρ0 cells, as evidenced by caspase activity and DNA degradation in response to cycloheximide and TNF-α treatment (Fig. 8, C and D). However, we cannot definitively rule out alternative explanations for the resistance of A549 ρ0 cells to bleomycin, such as unknown alterations in the cell apoptotic mechanisms.

Finally, we investigated the effect of bleomycin on MMP, another important mitochondrial apoptotic parameter (14). Preservation of MMP is essential for cell survival. MMP plays an important role in ATP generation, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (8), metabolite and protein transport (26), production of ROS, and apoptosis. In our study, when A549 cells were treated with bleomycin, loss of MMP was observed at 12 h and gradually increased over 48 h (Fig. 7). This time frame coincided with translocation of Bax into mitochondria and activation of caspase-3, PARP, and PKD1. In addition, changes in MMP were associated with a decrease in ATP levels by 48 h (data not shown). In prior studies, ρ0 cells exhibited little or no MMP (6, 36, 47); similarly, MMP was markedly reduced in A549 ρ0 cells (data not shown). Thus there was no way to directly compare the MMP response to bleomycin in the A549 parent cell line with that in the ρ0 cell line.

There were several limitations to our study. 1) We used A549 cells, a commonly used cell line for lung injury studies; however, these cells were originally derived from human lung cancer and may not accurately reflect responses of normal alveolar epithelial cells. Ideally, we would have used freshly isolated type II alveolar epithelial cells, as used previously in our laboratory (49). However, these cells cannot be successfully passaged multiple times, a requirement for induction of mtDNA deficiency. 2) The method used to deplete cells of mtDNA has multiple untoward effects on the health of the mitochondria and likely interferes with several key mitochondrial pathways, not simply the classic pathways presented in this study. 3) Cell culture studies are, by definition, artificial and are, by themselves, insufficient to predict similar responses in vivo regarding how intact organs such as the lung would respond to bleomycin or other oxidant stresses. Our study is consistent with prior work using other cytotoxic agents and cell lines (9, 29) but extends the observations to include the role of mitochondria in lung cell responses to bleomycin using more precise measures of critical mitochondrial-dependent pathways such as PKD1.

In summary, bleomycin induced more time- and concentration-dependent mtDNA than nDNA damage in A549 cells. Furthermore, bleomycin treatment led to apoptosis by cleavage and activation of caspase-3, PARP, and PKD1, by translocation of Bax, and by change in MMP. However, bleomycin caused no cleavage and activation of caspase-3, PARP, and PKD1 and no significant apoptosis in A549 ρ0 cells. The interplay between the functions of the mitochondria with multiple interdependent apoptotic pathways and the response to oxidative stress may be important in understanding the mechanisms of injury that occur during bleomycin-induced lung injury.

GRANTS

This research was supported in whole by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.S.B. and W.J.M.II are responsible for conception and design of the research; S.S.B., J.N.M., and C.D.B. performed the experiments; S.S.B., J.N.M., C.D.B., B.V.H., and W.J.M.II analyzed the data; S.S.B., J.N.M., C.D.B., B.V.H., and W.J.M.II interpreted the results of the experiments; S.S.B., J.N.M., and C.D.B. prepared the figures; S.S.B., B.V.H., and W.J.M.II drafted the manuscript; S.S.B., B.V.H., and W.J.M.II edited and revised the manuscript; W.J.M.II approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Drs. William Copeland and Michael Fessler for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions, Dr. Grace Kissling (Biostatistics Branch, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences) for assistance with statistical analysis, and Vijaylakshmi Panduri for assistance with A549 ρ0 cell culture.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adams JM. Ways of dying: multiple pathways to apoptosis. Genes Dev 17: 2481–2495, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Antonsson B, Martinou JC. The Bcl-2 protein family. Exp Cell Res 256: 50–57, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnould T, Vankoningsloo S, Renard P, Houbion A, Ninane N, Demazy C, Remacle J, Raes M. CREB activation induced by mitochondrial dysfunction is a new signaling pathway that impairs cell proliferation. EMBO J 21: 53–63, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bandy B, Davison AJ. Mitochondrial mutations may increase oxidative stress: implications for carcinogenesis and aging? Free Radic Biol Med 8: 523–539, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biswas G, Adebanjo OA, Freedman BD, Anandatheerthavarada HK, Vijayasarathy C, Zaidi M, Kotlikoff M, Avadhani NG. Retrograde Ca2+ signaling in C2C12 skeletal myocytes in response to mitochondrial genetic and metabolic stress: a novel mode of inter-organelle crosstalk. EMBO J 18: 522–533, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buchet K, Godinot C. Functional F1-ATPase essential in maintaining growth and membrane potential of human mitochondrial DNA-depleted ρ0 cells. J Biol Chem 273: 22983–22989, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Desjardins P, Frost E, Morais R. Ethidium bromide-induced loss of mitochondrial DNA from primary chicken embryo fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol 5: 1163–1169, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dykens JA. Isolated cerebral and cerebellar mitochondria produce free radicals when exposed to elevated Ca2+ and Na+: implications for neurodegeneration. J Neurochem 63: 584–591, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Endo K, Oki E, Biedermann V, Kojima H, Yoshida K, Johannes FJ, Kufe D, Datta R. Proteolytic cleavage and activation of protein kinase Cμ by caspase-3 in the apoptotic response of cells to 1β-d-arabinofuranosylcytosine and other genotoxic agents. J Biol Chem 275: 18476–18481, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fuchs F, Westermann B. Role of Unc104/KIF1-related motor proteins in mitochondrial transport in Neurospora crassa. Mol Biol Cell 16: 153–161, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Green DR, Reed JC. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science 281: 1309–1312, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haworth RS, Goss MW, Rozengurt E, Avkiran M. Expression and activity of protein kinase D/protein kinase Cμ in myocardium: evidence for α1-adrenergic receptor- and protein kinase C-mediated regulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 32: 1013–1023, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. He YH, 2nd, Wu M, Kobune M, Xu Y, Kelley MR, Martin WJ. Expression of yeast apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (APN1) protects lung epithelial cells from bleomycin toxicity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 25: 692–698, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Henry-Mowatt J, Dive C, Martinou JC, James D. Role of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in apoptosis and cancer. Oncogene 23: 2850–2860, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hunter SE, Jung D, Di Giulio RT, Meyer JN. The qPCR assay for analysis of mitochondrial DNA damage, repair, and relative copy number. Methods 51: 444–451, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Itahana K, Clegg HV, Zhang Y. ARF in the mitochondria: the last frontier? Cell Cycle 7: 3641–3646, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. King MP, Attardi G. Isolation of human cell lines lacking mitochondrial DNA. Methods Enzymol 264: 304–313, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lazebnik YA, Kaufmann SH, Desnoyers S, Poirier GG, Earnshaw WC. Cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase by a proteinase with properties like ICE. Nature 371: 346–347, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnemri ES, Wang X. Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell 91: 479–489, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lim LO, Neims AH. Mitochondrial DNA damage by bleomycin. Biochem Pharmacol 36: 2769–2774, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ly JD, Grubb DR, Lawen A. The mitochondrial membrane potential (δψm) in apoptosis: an update. Apoptosis 8: 115–128, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mahmutoglu I, Scheulen ME, Kappus H. Oxygen radical formation and DNA damage due to enzymatic reduction of bleomycin-Fe(III). Arch Toxicol 60: 150–153, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martin WJ, 2nd, Kachel DL. Bleomycin-induced pulmonary endothelial cell injury: evidence for the role of iron-catalyzed toxic oxygen-derived species. J Lab Clin Med 110: 153–158, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mercy L, Pauw A, Payen L, Tejerina S, Houbion A, Demazy C, Raes M, Renard P, Arnould T. Mitochondrial biogenesis in mtDNA-depleted cells involves a Ca2+-dependent pathway and a reduced mitochondrial protein import. FEBS J 272: 5031–5055, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nass MM. Abnormal DNA patterns in animal mitochondria: ethidium bromide-induced breakdown of closed circular DNA and conditions leading to oligomer accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 67: 1926–1933, 1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Neupert W. Protein import into mitochondria. Annu Rev Biochem 66: 863–917, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O'Reilly MA. DNA damage and cell cycle checkpoints in hyperoxic lung injury: braking to facilitate repair. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L291–L305, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Olive PL. The role of DNA single- and double-strand breaks in cell killing by ionizing radiation. Radiat Res 150: S42–S51, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Park SY, Chang I, Kim JY, Kang SW, Park SH, Singh K, Lee MS. Resistance of mitochondrial DNA-depleted cells against cell death: role of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem 279: 7512–7520, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Povirk LF. DNA damage and mutagenesis by radiomimetic DNA-cleaving agents: bleomycin, neocarzinostatin and other enediynes. Mutat Res 355: 71–89, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Repine JE, Bast A, Lankhorst I. Oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Oxidative Stress Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156: 341–357, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rozengurt E, Rey O, Waldron RT. Protein kinase D signaling. J Biol Chem 280: 13205–13208, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Santos JH, Hunakova L, Chen Y, Bortner C, Van Houten B. Cell sorting experiments link persistent mitochondrial DNA damage with loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptotic cell death. J Biol Chem 278: 1728–1734, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Santos JH, Meyer JN, Mandavilli BS, Van Houten B. Quantitative PCR-based measurement of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA damage and repair in mammalian cells. Methods Mol Biol 314: 183–199, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schapira AH. Mitochondrial involvement in Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, hereditary spastic paraplegia and Friedreich's ataxia. Biochim Biophys Acta 1410: 159–170, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sherer TB, Trimmer PA, Parks JK, Tuttle JB. Mitochondrial DNA-depleted neuroblastoma (ρ0) cells exhibit altered calcium signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta 1496: 341–355, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Storz P, Doppler H, Ferran C, Grey ST, Toker A. Functional dichotomy of A20 in apoptotic and necrotic cell death. Biochem J 387: 47–55, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Storz P, Doppler H, Toker A. Protein kinase D mediates mitochondrion-to-nucleus signaling and detoxification from mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell Biol 25: 8520–8530, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Storz P, Toker A. Protein kinase D mediates a stress-induced NF-κB activation and survival pathway. EMBO J 22: 109–120, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Van Houten B, Cheng S, Chen Y. Measuring gene-specific nucleotide excision repair in human cells using quantitative amplification of long targets from nanogram quantities of DNA. Mutat Res 460: 81–94, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van Lint J, Rykx A, Maeda Y, Vantus T, Sturany S, Malhotra V, Vandenheede JR, Seufferlein T. Protein kinase D: an intracellular traffic regulator on the move. Trends Cell Biol 12: 193–200, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vantus T, Vertommen D, Saelens X, Rykx A, De Kimpe L, Vancauwenbergh S, Mikhalap S, Waelkens E, Keri G, Seufferlein T, Vandenabeele P, Rider MH, Vandenheede JR, Van Lint J. Doxorubicin-induced activation of protein kinase D1 through caspase-mediated proteolytic cleavage: identification of two cleavage sites by microsequencing. Cell Signal 16: 703–709, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Waldron RT, Rey O, Iglesias T, Tugal T, Cantrell D, Rozengurt E. Activation loop Ser744 and Ser748 in protein kinase D are transphosphorylated in vivo. J Biol Chem 276: 32606–32615, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Waldron RT, Rey O, Zhukova E, Rozengurt E. Oxidative stress induces protein kinase C-mediated activation loop phosphorylation and nuclear redistribution of protein kinase D. J Biol Chem 279: 27482–27493, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Waldron RT, Rozengurt E. Protein kinase C phosphorylates protein kinase D activation loop Ser744 and Ser748 and releases autoinhibition by the pleckstrin homology domain. J Biol Chem 278: 154–163, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wiseman H, Halliwell B. Damage to DNA by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: role in inflammatory disease and progression to cancer. Biochem J 313: 17–29, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wong A, Cortopassi GA. High-throughput measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential in a neural cell line using a fluorescence plate reader. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 298: 750–754, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu M, He YH, Kobune M, Xu Y, Kelley MR, Martin WJ., 2nd Protection of human lung cells against hyperoxia using the DNA base excision repair genes hOgg1 and Fpg. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166: 192–199, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wu M, Kelley MR, Hansen WK, Martin WJ., 2nd Reduction of BCNU toxicity to lung cells by high-level expression of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L755–L761, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yakes FM, Van Houten B. Mitochondrial DNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nuclear DNA damage in human cells following oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 514–519, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]