Abstract

Laboratory evidence suggests that intestinal permeability is elevated following either binge ethanol exposure or burn injury alone, and this barrier dysfunction is further perturbed when these insults are combined. We and others have previously reported a rise in both systemic and local proinflammatory cytokine production in mice after the combined insult. Knowing that long myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK) is important for epithelial barrier maintenance and can be activated by proinflammatory cytokines, we examined whether inhibition of MLCK alleviated detrimental intestinal responses seen after ethanol exposure and burn injury. To accomplish this, mice were given vehicle or a single binge ethanol exposure followed by a sham or dorsal scald burn injury. Following injury, one group of mice received membrane permeant inhibitor of MLCK (PIK). At 6 and 24 h postinjury, bacterial translocation and intestinal levels of proinflammatory cytokines were measured, and changes in tight junction protein localization and total intestinal morphology were analyzed. Elevated morphological damage, ileal IL-1β and IL-6 levels, and bacterial translocation were seen in mice exposed to ethanol and burn injury relative to either insult alone. This increase was not seen in mice receiving PIK after injury. Ethanol-exposed and burn-injured mice had reduced zonula occludens protein-1 and occludin localization to the tight junction relative to sham-injured mice. However, the observed changes in junctional complexes were not seen in our PIK-treated mice following the combined insult. These data suggest that MLCK activity may promote morphological and inflammatory responses in the ileum following ethanol exposure and burn injury.

Keywords: ZO-1, occludin, bacterial translocation, permeability

nearly one million burn injuries occur annually in the United States with ∼4,000 patients succumbing to their injuries (2a). Both clinical and laboratory studies indicate that intestinal permeability and tissue injury increase after burn injury, permitting bacteria to translocate into the lymphatic system and ultimately the bloodstream (13, 30). In a rodent model of binge ethanol exposure and burn injury, Kavanaugh and colleagues (9, 27) demonstrated that the combined insult promotes greater bacterial translocation to the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) and intestinal permeability than in mice receiving either treatment alone. The distal small intestine and colon contains enormous volumes of bacteria (105-108 bacteria per gram of tissue) and endotoxin; therefore, changes in intestinal permeability could produce systemic complications. Intestinal barrier dysfunction/failure allowing gut flora and its components to invade the intestinal mucosa is the basis for the gut-lymph hypothesis of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (17), which states that traumatic injury promotes a rise in intestinal permeability leading to a release of bacteria and endotoxin into the lymphatic system and ultimately the bloodstream. As the bacteria-laden blood encounters the lung vascular bed first, pulmonary injury is possible, thus promoting the early stages of MODS (17, 18) and ultimately multiple organ failure, which are the two most common causes of death after burn injury (41, 51).

Intestinal epithelial cells, physically connected by multiple types of junction complexes, create a semipermeable mucosal barrier that permits absorption of nutrients but prevents other contents of the lumen from entering the lamina propria (52, 53). Regulation of this barrier can be affected by various stimuli, including bacteria, cytokines, traumatic injury, and ethanol (6, 29, 30, 36). Junction proteins, such as the tight junction proteins zonula occludens protein-1 (ZO-1) and occludin, as well as enzymes important for the maintenance of this barrier can be affected by these stimuli. One such enzyme, long (210 kDa) myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK), phosphorylates myosin regulatory light-chain (MLC) at serine 19 allowing it to interact with actin. Myosin-actin interaction causes cytoskeletal sliding, which induces tight junction disruption and a gap in the epithelial barrier. Actin reorganization, elevated permeability, and ZO-1 and occludin redistribution away from tight junctions are associated with MLC phosphorylation (39, 46).

Inflammatory diseases and traumatic injury amplify proinflammatory cytokines in the gut (10, 41). A rise in proinflammatory cytokines is associated with MLCK activation, and it has been shown that TNF-α, IL-1β, and lymphotoxin-like inducible protein that competes with glycoprotein D for herpesvirus entry mediator on T cells (LIGHT) can upregulate MLCK transcription (2, 12, 25, 29, 30, 36). Furthermore, increased MLCK activation has been linked to intestinal permeability after burn injury or chronic ethanol exposure alone (29, 50). Traumatic injury, like burn, causes an overexuberant systemic inflammatory response characterized by a rise in systemic and tissue levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β (22, 34, 43, 44). When injury is combined with ethanol exposure, these immune responses are often further increased. Recently, a specific membrane permeant inhibitor of MLCK (PIK), was found to reduce occludin reorganization away from tight junctions and restore water absorption in a model of T cell-mediated diarrhea (11). Moreover, TNF-α and interferon-γ-induced barrier dysfunction was reversed with PIK treatment (57).

Ethanol is a common risk factor in traumatic injury (26, 31), and ∼50% of the adult burn patient population has a positive blood alcohol content at the time of admission (33, 49). Further evidence suggests that the combination of ethanol and burn injury leads to enhanced immunosuppression promoting greater susceptibility to bacterial infection at both the wound site as well as remote organs, such as the lung and ileum (4, 24, 35).

The combination of insult-induced immunosuppression and inflammation along with amplified bacterial translocation in the gut contribute to a physiological state that is ideal for tissue destruction and dysfunction. We hypothesized that inhibition of MLCK would alleviate the intestinal damage and inflammatory responses seen after binge ethanol exposure and burn injury. Mice had greater villus blunting and edema as well as a redistribution of ZO-1 and occludin following ethanol and burn injury compared with sham-treated mice. These changes coincided with elevated phosphorylated MLC (pMLC), bacterial translocation and ileum IL-6 levels. In contrast, PIK-treated mice exposed to ethanol and burn injury had significantly reduced intestinal damage, normal tight-junction protein localization, and decreased bacterial translocation and IL-6. This indicates a crucial role for MLCK in intestinal barrier leakiness and/or inflammation in our model of ethanol and burn injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Eight- to ten-week-old male (C57BL/6, 23–25 g,) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed in sterile microisolator cages in the Loyola University Medical Center Comparative Medicine facility. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Loyola Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Murine model of ethanol and burn injury.

A murine model of a single binge ethanol exposure and burn injury was performed as described previously (20) with minor modifications (38). Briefly, mice were given a single binge dose of 1.11 g/kg of 20% (vol/vol) ethanol solution intraperitoneally that resulted in a blood ethanol level of 150–180 mg/dl at 30 min. The mice were then anesthetized with 100 mg/kg of ketamine and 10 mg/kg of Xylazine (Webster Veterinary, Sterling, MA), their dorsum was shaved, and they were placed in a plastic template exposing 15% of the total body surface area and subjected to a scald injury in 90–92°C water bath or a sham injury in room temperature water. The scald injury resulted in an insensate, full-thickness burn injury of ∼15% total body surface area (21). Mice received 1 ml of saline resuscitation, and their cages were placed on warming pads until mice recovered from anesthesia. At 30 min after burn injury, mice were given the specific long MLCK inhibitor PIK (50 μM) (40). Mice were killed by CO2 narcosis followed by cervical dislocation at 2, 3, 6, or 24 h following injury.

Histopathologic examination of the ileum.

At 6 and 24 h postinjury, mice were euthanized by CO2 narcosis, and the ileum was harvested and fixed overnight in 10% formalin. Samples were then embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μ, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Images were taken at magnification, ×200.

Immunofluorescent staining of ZO-1 and occludin in the ileum.

Immunofluorescent staining was done as previously described (11) with minor modifications. Briefly, a small section of ileum (5 mm) was embedded in OCT and frozen for immunofluorescent staining. The ileum was sectioned (5 μ) and stained with either rabbit anti-ZO-1 or rabbit anti-occludin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) followed by goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen). Sections were further stained with fluorescent-conjugated phalloidin (actin) and Hoechst nuclear stain (Invitrogen). Using Zeiss software (model LSM 510, version 4.2 SP1), a 20-epithelial cell section (crypt or villus) was outlined; only within this outlined section were the number of colocalized (both red and green fluorescence) pixels determined. The number of colocalized pixels was divided by the total number of pixels in that section and expressed as a percentage. This process was repeated on an additional four epithelial cell sections per animal, leading to 100 total epithelial cells examined for each animal. Results were averaged for each animal, and this average was then used to determine the group average.

Bacterial translocation.

Bacterial translocation was assessed as previously described with minor modifications (27). Briefly, 5–6 MLN per mouse were removed at 6 or 24 h, placed in cold RPMI, and kept on ice. Nodes were separated from connective tissue and homogenized in RPMI using frosted glass slides. Homogenates were plated in triplicate on tryptic soy agar plates and placed in a 37°C incubator overnight. Colonies were counted the following day, averaged, and divided by the total number of lymph nodes harvested.

Intestinal epithelial cell isolation and Western blot analysis.

Intestinal epithelial cells were isolated as previously described (11) with minor modifications. Briefly, ileum sections were opened lengthwise, washed with calcium and magnesium-free HBSS, and placed in tubes containing 10 mM DTT and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail in HBSS. Samples were placed at 4°C for 30 min, after which tubes were shaken briefly, and ileum sections moved to tubes containing 1 mM EDTA and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail in HBSS for 1 h at 4°C. After incubation, tubes were shaken robustly and large pieces of tissue removed. Samples were centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded. Pelleted cells were lysed in 100 μl of cell lysis buffer according to the manufacturer's protocol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Twenty milligrams of whole cell lysate protein was boiled for 5 min, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes and blotted with primary antibodies specific for phopshorylated MLC (pMLC; Ser19; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), total MLCK (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and villin-1 (Cell Signaling Technology).

Detection of circulating cytokine levels.

Blood was collected from cardiac puncture, and serum was obtained by centrifugation after clotting. IL-6 and TNF-α levels were then determined using ELISA according to manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA).

Cytokine determination in ileum.

Two one-inch sections of ileum were homogenized in 1 ml of cell lysis buffer according to manufacturer's protocol (Bio-Rad). Homogenates were then filtered and analyzed for IL-6 levels using ELISA (BD Biosciences, San Diego CA). The results were normalized to total protein present in the homogenate using the Bio-Rad protein assay based on the methods of Bradford (5).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical comparisons (GraphPad Instat and Prism) were made between the sham vehicle, sham ethanol, burn vehicle, and burn ethanol treatment groups, resulting in four total groups analyzed. One-way ANOVA was used to determine differences between treatment responses, and Tukey's post hoc test once significance was achieved (P < 0.05). Statistical comparisons made between the burn ethanol and burn ethanol plus PIK treatment groups were done using Student's t-test and Tukey's post hoc test (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

Following exposure to binge ethanol and burn injury, a rise in IL-6 and intestinal permeability as well as a shortening of villus heights has been observed in the ileum (42). These changes can promote further tissue damage and may contribute to systemic complications. We sought to determine whether inhibition of MLCK after insult alleviates these detrimental responses.

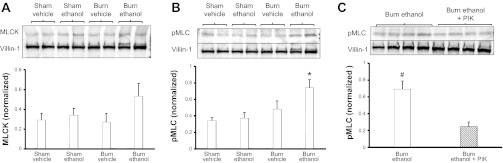

MLCK activated early after insult.

TNF-α often peaks early systemically after injury (19) and we see an increase in serum levels at 2 h after ethanol exposure and burn injury (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, IL-6 levels, thought to peak at later time points, were also significantly elevated in the serum at 2 h postinsult (Fig. 1B). Neither TNF-α nor IL-6 is significantly elevated in ileum tissue (Fig. 1, C and D); however, we do see an increase in total MLCK in intestinal epithelial cells isolated from ethanol-exposed and burn-injured mice (Fig. 2A) at 3 h after combined insult. This elevation was not significant, but dually exposed mice did have a significant increase in pMLC compared with all other groups (Fig. 2B), and PIK treatment significantly reduced pMLC following ethanol exposure and burn injury (Fig. 2C). These data suggest that within a few hours of the combined insult the MLCK pathway has been activated, possibly due to elevated serum levels of TNF-α and IL-6.

Fig. 1.

TNF-α and IL-6 elevated in serum at 2 h after insult. Levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were quantified by ELISA. An increase in serum levels of TNF-α (A) was observed at 2 h after ethanol exposure and burn injury. IL-6 (B) levels were also significantly elevated in the serum at 2 h postinsult. Cytokine concentrations were normalized to total protein in ileum samples (C and D) as determined by Bio-Rad protein assay. All data are presented as concentration ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. both sham groups; n = 3–6 per group.

Fig. 2.

Ethanol exposure and burn injury elevates total myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK) and phosphorylated MLC (pMLC; Ser19) in intestinal epithelial cells. Isolated intestinal epithelial cells were lysed and analyzed by Western blot analysis for levels of MLCK (A) and pMLC (B and C) 3 h after exposure to treatment. Quantification of MLCK and pMLC levels were normalized to villin-1 levels and done using Bio-Rad Image Lab software. Images are representative of 3 experiments, *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups, #P < 0.05 vs. burn ethanol + membrane permeant inhibitor of MLCK (PIK) group. Quantification is of n = 6–8 per group.

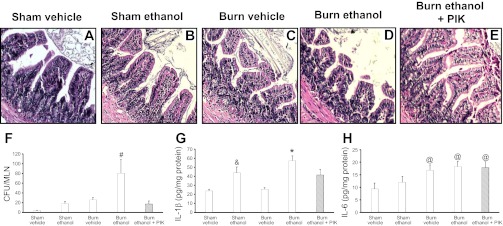

Morphological damage observed by 6 h after ethanol exposure and burn injury.

Intestinal damage, characterized by villus blunting and edema as well as intestinal inflammation, commonly occurs after traumatic injury (14, 16, 48). Six hours after exposure to ethanol and burn injury, ileum morphology begins to change. Mice in both burn groups had blunted villi (Fig. 3, C and D) compared with mice in either sham group (Fig. 3, A and B). The intestinal epithelial layer is also altered in mice exposed to the combined insult with gaps appearing between epithelial cells, although no changes in ZO-1 or occludin localization were observed at this time (data not shown). Inhibition of MLCK using PIK yields to little or no change in the intestinal epithelial barrier morphology following exposure to ethanol and burn injury (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

PIK treatment reduces morphological damage and inflammation at 6 h after combined insult. Ileum sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A–E) and examined for degree of inflammation and damage (n = 6–8 per group). Mesenteric lymph nodes were isolated from mice killed at 6 h following insult (F). Lymph nodes were homogenized and plated on tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates. Colonies were counted the next day and normalized on the total number of lymph nodes removed from each mouse. Levels presented as concentration ± SE. #P < 0.05 vs. all other groups (n = 6–10 per group). Ileum levels of IL-1β and IL-6 were quantified by ELISA (G and H) and normalized to total protein. Data presented as concentration ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. all groups except the sham ethanol group; &P < 0.05 vs. sham vehicle and burn vehicle (n = 3–6 per group); @P < 0.05 vs. sham vehicle (n = 3–6 per group).

After either traumatic injury or chronic ethanol exposure, bacterial translocation was reported to be elevated as a result of epithelial cell damage, bacterial overgrowth, epithelial barrier permeability and MLN T-cell suppression (8, 27). This translocation occurs in small amounts in healthy individuals, and under normal conditions, MLN resident T cells clear the bacteria (8). Six hours after ethanol exposure and burn injury mice had significantly greater bacterial accumulation in the MLN compared with all other groups (Fig. 3F). This elevation in bacterial accumulation was associated with a rise in ileum levels of IL-1β and IL-6 (Fig. 3, G and H). PIK treatment significantly reduced bacterial accumulation in the MLN of mice given ethanol and burn injury and also decreased IL-1β in the ileum (Fig. 3, F and G). These data indicate that the continued inhibition of MLCK preserves intestinal morphology and reduces inflammation following ethanol exposure and burn injury.

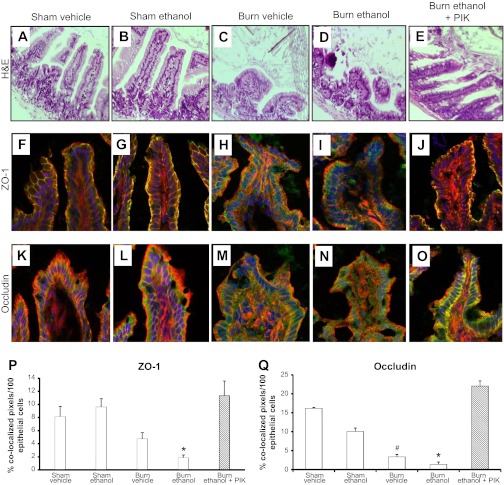

PIK treatment alleviates intestinal epithelial barrier alterations.

Previous work in this model has revealed that the heights of villi are lower at 24 h following the combined insult (42). This response was verified in these experiments as villi in mice exposed to burn alone or the combined insult (Fig. 4, C and D) had shorter (115 μm ± 9) and wider villi than sham-treated animals (200 μm ± 14, P < 0.05, Fig. 4, A and B). Furthermore, there was a decrease in intact villi and the epithelial cell layer in mice given ethanol and burn injury compared with all other groups. As seen at 6 h, PIK treatment was coupled with reduced intestinal morphological damage (Fig. 4E) as mice given PIK after ethanol and burn injury had tall (170 μm ± 9) and narrow villi similar to villi seen in sham-treated mice. Since greater morphological damage was observed at 24 h following insult, we examined the effect of ethanol and burn injury on the localization of two of the major tight junction proteins in the ileal epithelial cell layer, ZO-1, and occludin (23). Intact tight junction complexes in the intestinal epithelial layer prevent bacteria and their products from moving into the lamina propria and initiating an immune response. Representative images from wild-type sham vehicle and sham ethanol mice (Fig. 4, F and G) show ZO-1 in its characteristic chicken-wire pattern, and its colocalization with actin indicating an intact tight junction. Animals exposed to burn injury alone had a slight, but insignificant, decrease in ZO-1 localizing with actin (Fig. 4H), while almost no ZO-1 colocalizes with actin in animals exposed to the combined insult (Fig. 4I). Quantification of ZO-1 and actin colocalization (Fig. 4P) indicated that significantly less ZO-1 colocalized with actin in wild-type mice exposed to ethanol and burn injury than in sham-treated animals. PIK treatment of wild-type mice exposed to the combined insult preserved ZO-1 localization at the periphery of cells and its interaction with actin (Fig. 4, J and P). Occludin position can be affected by a variety of stimuli including burn injury alone, acetaldehyde (the predominant ethanol metabolite), TNF-α, and LIGHT (3, 8, 12, 46). Occludin localization alterations were also observed by visual examination, but this decrease in colocalization was not as obvious as found with ZO-1 (Fig. 4, K–O). Quantification, however, of occludin and actin colocalization indicated that association of occludin and actin was significantly reduced in mice exposed to the burn injury alone or the combined insult, and this localization was reestablished in mice receiving PIK after ethanol exposure and burn injury compared with mice not receiving PIK treatment (Fig. 4, O and Q). As seen at 6 h after insult, MLCK inhibition continues to decrease intestinal damage and intestinal epithelial cell barrier alterations induced following ethanol exposure and burn injury.

Fig. 4.

MLCK inhibition preserves intestinal morphology and tight junction protein localization following ethanol exposure and burn injury. Ileum sections from mice were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A–E) and then examined for degree of inflammation and damage. Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images were taken at magnification, ×200. Frozen ileum sections were stained with antibodies against zonula occludens protein-1 (ZO-1; green, F–J) or occludin (green, K–O) as well as phalloidin (red) and nuclei (blue). Representative immunofluorescent images were taken at magnification, ×400 (n = 6–8 per group). Immunofluorescent images were analyzed for colocalization of ZO-1 or occludin with actin (P and Q). Colocalization is presented as % colocalized pixels/100 epithelial cells. *P < 0.05 vs. all groups except burn vehicle, #P < 0.05 vs. sham groups (n = 4–6 per group).

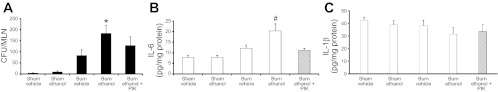

Intestinal damage and inflammation reduced following PIK treatment.

In conjunction with a reduction in intestinal morphological damage as observed in Fig. 4, PIK treatment also led to a 33% reduction in bacterial translocation at 24 h after insult; however, this difference was not significant (Fig. 5A). This reduction is likely due to the decrease seen at 6 h, but to maintain this reduction another dose of PIK may be needed. Although bacterial translocation was not reduced following PIK treatment, IL-6 levels in the ileum were significantly less in PIK-treated mice exposed to ethanol and burn injury compared with mice not receiving PIK (Fig. 5B). By 24 h following insult, no differences in IL-1β levels were observed between groups (Fig. 5C). As seen in Fig. 4, early inhibition of MLCK alleviates intestinal damage and inflammation and preserves tight junctions in the intestinal epithelial barrier at 24 h after combined insult.

Fig. 5.

Decreased IL-6 following PIK treatment in mice exposed to ethanol and burn injury. Mesenteric lymph nodes were isolated from mice killed at 24 h following insult (A). Lymph nodes were homogenized and plated on TSA plates. Colonies were counted the next day and normalized to the total number of lymph nodes removed from each mouse. Levels are presented as concentration ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups except burn ethanol + PIK (n = 6–8 per group). IL-6 (B) and IL-1β (C) levels in the ileum were measured by ELISA and normalized to total protein per sample. Data presented as concentration ± SE. #P < 0.05 vs. all other groups (n = 4–6 per group).

These data confirm previous studies that gut inflammation is greater after ethanol exposure and burn injury than burn injury alone. Furthermore, the loss or inhibition of MLCK promotes maintenance of intestinal epithelial tight junctions after ethanol and burn, thereby preventing bacterial translocation and the subsequent immune response and leading to less intestinal damage and inflammation.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies in a rodent model have shown that binge ethanol exposure and burn injury can cause intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation (8, 9); however, the possible mechanism of these changes has not been determined. The results described in the present study indicate that after the combined insult of ethanol exposure and burn injury MLCK contributes to alterations in tight junction localization, bacterial translocation, along with intestinal inflammation and damage. PIK-treated mice had a reduction in these parameters including less villus blunting, edema, destruction of the intestinal epithelial layer, and tight junction protein localization alterations compared with similarly treated wild-type mice not receiving PIK (Fig. 4). Although MLCK is an enzyme necessary for epithelial barrier maintenance, inhibition of MLCK could be beneficial for decreasing intestinal morphological damage and inflammation following ethanol and burn injury. This decline in morphological damage corresponded with reduced ileum IL-6 levels in PIK-treated mice (Fig. 5). While PIK-treated mice did not have significantly lower bacterial translocation 24 h after the combined insult, it was 33% less than ethanol-exposed and burn-injured mice not given PIK. It is likely that more than one PIK administration would be necessary to significantly reduce bacterial translocation at later time points, which is an ongoing study in our laboratory. Studies examining immune cell function suggest that bacterial accumulation in the MLN occurs in a model of ethanol exposure and burn injury, likely due to decreased T cell proliferation and reduced production of IL-2 and interferon-γ (8, 9). Moreover, previous work in our model indicates an increase in ileum levels of IL-10 at 24 h after combined insult (42). Overall these data suggest that the combination of ethanol exposure and burn injury not only affect barrier permeability but also delay resolution of bacteria in the MLN allowing for bacterial accumulation and the possibility of bacterial dissemination.

Alterations in intestinal permeability have long been studied as the cause or outcome of numerous diseases and injuries. Common in chronic inflammatory disorders, such as inflammatory bowel syndrome, elevated intestinal barrier dysfunction may contribute to progression of the disease due to a continuous immune response (47). Proinflammatory mediators, particularly TNF-α, LIGHT (a member of the TNF-α superfamily), IL-1β, and IL-6 have all been shown to increase intestinal permeability in animal models of hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation, diarrhea, and epithelial barrier dysfunction (12, 55, 56). Of these cytokines, most studies have focused on TNF-α in barrier dysfunction. TNF-α was shown to directly upregulate MLCK transcription as well as protein levels (25, 54) and the cytokine also promotes occludin internalization (12, 45). In models of inflammatory bowel disease, antagonism of TNF-α resulted in partial restoration of T-cell mediated barrier dysfunction (11); however, in our model of binge ethanol exposure and burn injury, we only see an early rise in serum levels of TNF-α. This initial rise in TNF-α suggests that it could still be an activator of MLCK, as our elevation in MLCK and pMLC are observed early after the insult as well. Furthermore, TNF-α is also known to increase levels of other proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-6, which may be important regulators of the alterations seen in the intestine after exposure to the combined insult. In line with this thought, we observed an increase in ileum levels of IL-1β at 6 h and IL-6 at 24 h following the combined insult (Figs. 3 and 5). Interestingly, IL-6 was also elevated in the serum at 2 h after combined insult, and previous work indicates that it remains elevated until at least 24 h (22). Taken together, these data indicate that both TNF-α and IL-6 may have a role in activation of the MLCK pathway and later tissue damage, inflammation, and alterations in the intestinal barrier.

Our studies support previous work that ethanol exposure combined with burn injury causes additive damage on intestinal barrier dysfunction than burn injury or ethanol exposure alone. Choudhry and colleagues (8, 27) have shown greater bacterial translocation to the MLN in a rat model of ethanol exposure and burn injury. This correlated with increased in vivo gut permeability and bacterial overgrowth, but not with changes in intestinal morphology. Furthermore, intestinal edema and MPO were higher in mice exposed to the combined insult than in mice given either injury alone (28). Neutrophil depletion or anti-IL-18 antibody treatment reduced ileum neutrophil infiltration and MPO levels in the same model (1, 28). The findings presented in this study are similar to those previously published by our group and others despite using a slightly different model (27, 42). We do, however, find greater intestinal morphological damage than was observed seen in other models of ethanol exposure and burn injury. This difference in intestinal damage might be attributed to subtle differences in ethanol administration, timing of administration relative to injury, peak blood alcohol level, or small variations in burn injury protocol; however, both models produce elevations in inflammation and barrier dysfunction.

Unlike previous studies, data presented here show, for the first time, a possible mechanism, which could explain how the previously reported marked elevation in systemic and local levels of cytokine might trigger the observed increase in intestinal damage after exposure to ethanol and burn injury. While MLCK has been extensively studied in chronic inflammatory diseases, the role of this enzyme after a combined insult or other acute insults has not been as well defined. Using a MLCK inhibitor, we have demonstrated that MLCK functions in tight junction protein localization and subsequent bacterial translocation and inflammation in a model of ethanol exposure and burn injury. The mechanism of this restoration is currently being studied with several possible pathways being involved. MLCK activation is highly correlated with TNF-α, and while we do not see changes in TNF-α in the ileum after insult, it may very well be the predominant signal for MLCK activation. TNF-α signaling causes increases in both expression and protein levels of IL-6 (32) and MLCK (25) and can also activate numerous kinase cascades, which could easily lead to MLCK activation. Multiple pathways may converge leading to the damage and alterations seen in the ileum after the combined insult.

In summary, the results of this study indicate that inhibition of MLCK is beneficial for the reduction of intestinal damage, barrier leakiness, and inflammation after exposure to ethanol and burn injury. As previously stated, MODS and multiple organ failure are the most common outcomes of burn injury (41, 51). Recent clinical studies indicate that trauma-induced sepsis patients with a history of alcohol abuse have an increased risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome, the first stage of MODS (37). Interestingly, preliminary work in our laboratory suggests that PIK treatment also reduces the neutrophil chemokine KC in the lung as well as the total number of neutrophils infiltrating into the lung following ethanol exposure and burn injury. Furthermore, studies conducted in Loyola's Burn Intensive Care Unit demonstrate that intoxicated patients who suffer burn injuries have smaller burns than nondrinking burn patients, but spend the same number of days in the hospital, have as many days on the ventilator, and accrue the same amount of hospital costs as nondrinking patients with much larger burns (15). Thus, intoxicated patients with minor burn injuries suffer more complications than their not-drinking counterparts. Data presented here implicate that patients who suffer a burn injury with ethanol in their system may have impaired intestinal barrier function, thus contributing to an elevated state of inflammation and perhaps severe downstream complications. Overall, these data associate MLCK in the pathogenesis of binge ethanol and burn-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction and elevated intestinal inflammation and suggest a possible role for MLCK in other acute gastrointestinal injuries.

GRANTS

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-AA-012034 (to E. J. Kovacs), T32-AA-013527 (to E. J.Kovacs), F31-AA-019913 (to A. Zahs), P30-AA-019373 (to E. J.Kovacs), and R01-DK-068271 (to J. R. Turner), and the Margaret A. Baima Endowment Fund for Alcohol Research and the Ralph and Marian C. Falk Medical Research Trust.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: A.Z., M.D.B., J.R.T., M.A.C., and E.J.K. conception and design of research; A.Z., M.D.B., and L.R. performed experiments; A.Z., M.D.B., and E.J.K. analyzed data; A.Z., M.D.B., M.A.C., and E.J.K. interpreted results of experiments; A.Z. prepared figures; A.Z. drafted manuscript; A.Z., M.D.B., L.R., J.R.T., M.A.C., and E.J.K. edited and revised manuscript; A.Z., M.D.B., L.R., J.R.T., M.A.C., and E.J.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Sherri Yong for analysis of ileum pathology and thoughtful discussion of the project.

REFERENCES

- 1. Akhtar S, Li X, Chaundry IH, Choudhry MA. Neutrophil chemokines and their role in IL-18-mediated increase in neutrophil O2− production and intestinal edema following alcohol intoxication and burn injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297: G340–G347, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Al-Sadi RM, Ma TY. IL-1β causes an increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability. J Immunol 178: 4641–4649, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a. American Burn Association Burn Incidence and Treatment in the United States: 2011 Fact Sheet. http://www.ameriburn.org/resources_factsheet.php [Google Scholar]

- 3. Atkinson KJ, Rao RK. Role of protein tyrosine phosphorylation in acetaldehyde-induced disruption of epithelial tight junctions. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280: G1280–G1288, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bird MD, Kovacs EJ. Organ-specific inflammation following acute ethanol and burn injury. J Leukoc Biol 84: 607–613, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72: 248–254, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruewer M, Luegering A, Kucharzik T, Parkos CA, Madara JL, Hopkins AM, Nusrat A. Proinflammatory cytokines disrupt epithelial barrier function by apoptosis-independent mechanisms. J Immunol 171: 6164–6172, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choudhry MA, Fazal N, Goto M, Gamelli RL, Sayeed MM. Gut-associated T cell suppression enhances bacterial translocation in alcohol and burn injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 282: G937–G947, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choudhry MA, Rana SN, Kavanaugh MJ, Kovacs EJ, Gamelli RL, Sayeed MM. Impaired intestinal immunity and barrier function: a cause for enhanced bacterial translocation in alcohol intoxication and burn injury. Alcohol 33: 199–208, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clayburgh DR, Shen L, Turner JR. A porous defense: the leaky epithelial barrier in intestinal disease. Lab Invest 84: 283–291, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clayburgh DR, Barrett TA, Tang Y, Meddings JB, Van Eldik LJ, Watterson DM, Clarke LL, Mrsny RJ, Turner JR. Epithelial myosin light chain kinase-dependent barrier dysfunction mediates T cell activation-induced diarrhea in vivo. J Clin Invest 115: 2702–2715, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clayburgh DR, Musch MW, Leitges M, Fu YX, Turner JR. Coordinated epithelial NHE3 inhibition and barrier dysfunction are required for TNF-mediated diarrhea in vivo. J Clin Invest 116: 2682–2694, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Constantini TW, Loomis WH, Putnam JG, Kroll L, Eliceiri BP, Baird A, Bansal V, Coimbra R. Pentoxifylline modulates intestinal tight junction signaling after burn injury: effects on myosin light chain kinase. J Trauma 66: 17–25, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Constantini TW, Loomis WH, Putnam JG, Drusinsky D, Deree J, Choi S, Wolf P, Baird A, Eliceiri B, Bansal V, Coimbra R. Burn-induced gut barrier injury is attenuated by phosphodiesterase inhibition: effects on tight junction structural proteins. Shock 31: 416–422, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davis CS, Esposito TJ, Palladino-Davis AG, Rychlik K, Schermer CR, Gamelli RL, Kovacs EJ. Implications of alcohol intoxication at the time of burn and smoke inhalation injury: an epidemiologic and clinical analysis. J Burn Care Res. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Haan JJ, Lubbers T, Derikx JP, Relja B, Henrich D, Greve JW, Marzi I, Buurman WA. Rapid development of intestinal cell damage following severe trauma: a prospective observational cohort study. Crit Care 13: R86, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deitch EA. Role of the gut lymphatic system in multiple organ failure. Curr Opin Crit Care 7: 92–98, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Desai MH, Herndon DN, Rutan RL, Abston S, Linares HA. Ischemic intestinal complications in patients with burns. Surg Gynecol Obstet 31: 257–61, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Drost AC, Burleson DG, Cioffi WG, Jr, Jordan BS, Mason AD, Jr, Pruitt BA., Jr Plasma cytokines following thermal injury and their relationship with patient mortality, burn size, and time postburn. J Trauma 35: 335–339, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Faunce DE, Gregory MS, Kovacs EJ. Effects of acute ethanol exposure on cellular immune responses in a murine model of thermal injury. J Leukoc Biol 62: 733–740, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Faunce DE, Llanas JN, Patel PJ, Gregory MS, Duffner LA, Kovacs EJ. Neutrophil chemokine production in the skin following scald injury. Burns 25: 403–410, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fontanilla CV, Faunce DE, Gregory MS, Messingham KA, Durbin EA, Duffner LA, Kovacs EJ. Anti-interleukin-6 antibody treatment restores cell-mediated immune function in mice with acute ethanol exposure before burn trauma. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24: 1392–1399, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fries W, Maja C, Crisafulli C, Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E. Dynamics of enterocyte tight junctions: effects of experimental colitis and two different anti-TNF strategies. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G938–G947, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ghare S, Patil M, Hote P, Suttles J, McClain C, Barve S, Joshi-Barve S. Ethanol inhibits lipid raft-mediated TCR signaling and IL-2 expression: potential mechanism of alcohol-induced immune suppression. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35: 1435–1444, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graham WV, Wang F, Clayburgh DR, Cheng JX, Yoon B, Wang Y, Lin A, Turner JR. Tumor necrosis factor-induced long myosin light chain kinase transcription is regulated by differentiation-dependent signaling events. Characterization of the human long myosin light chain kinase promoter. J Biol Chem 281: 26205–26215, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Howland J, Hingson R. Alcohol as a risk factor for injuries or death due to fires and burns: review of the literature. Public Health Rep 102: 475–483, 1987 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kavanaugh MJ, Clark C, Goto M, Kovacs EJ, Gamelli RL, Sayeed MM, Choudhry MA. Effect of acute alcohol ingestion prior to burn injury on intestinal bacterial growth and barrier function. Burns 31: 290–296, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li X, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH, Choudhry MA. Acute alcohol intoxication potentiates neutrophil-mediated intestinal tissue damage after burn injury. Shock 29: 377–383, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ma TY, Nguyen D, Bui V, Nguyen H, Hoa N. Ethanol modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 276: G965–G974, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Magnotti LJ, Deitch EA. Burns, bacterial translocation, gut barrier function, and failure. J Burn Care Res 26: 383–391, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maier RV. Ethanol abuse and the trauma patient. Surg Inf 2: 133–142, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matsunaga T, Shoji A, Gu N, Joo E, Li S, Adachi T, Yamazaki H, Yasuda K, Kondoh T, Tsuda K. γ-Tocotrienol attenuates TNF-α-induced changes in secretion and gene expression of MCP-1, IL-6 and adiponectin in 3T3–L1 adipocytes. Mol Med Report 5: 905–909, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McGill V, Kowal-Vern A, Fisher SG, Kahn S, Gamelli RL. The impact of substance use on mortality and morbidity from thermal injury. J Trauma 38: 931–934, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Messingham KA, Fontanilla CV, Colantoni A, Duffner LA, Kovacs EJ. Cellular immunity after ethanol exposure and burn injury, dose and time dependence. Alcohol 22: 35–44, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Messingham KA, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Alcohol, injury, and cellular immunity. Alcohol 28: 137–149, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moriez R, Salvador-Cartier C, Theodorou V, Fioramonti J, Eutamene H, Bueno L. Myosin light chain kinase is involved in lipopolysaccharide-induced disruption of colonic epithelial barrier and bacterial translocation in rats. Am J Pathol 167: 1071–1079, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moss M, Parsons PE, Steinberg KP, Hudson LD, Guidot DM, Burnham EL, Eaton S, Cotsonis GA. Chronic alcohol abuse is associated with an increased incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome and severity of multiple organ dysfunction in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med 31: 869–877, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Murdoch EL, Brown HG, Gamelli RL, Kovacs EJ. Effects of ethanol on pulmonary inflammation in postburn intratracheal infection. J Burn Care Res 29: 323–330, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Murphy JT, Duffy S. ZO-1 redistribution and F-actin stress fiber formation in pulmonary endothelial cells after thermal injury. J Trauma 54: 81–90, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Owens SE, Graham VW, Siccardi D, Turner JR, Mrsny RJ. A strategy to identify stable membrane-permeant peptide inhibitors of myosin light chain kinase. Pharm Res 22: 703–709, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rangel EL, Butler KL, Johannigman JA, Tsuei BJ, Solomkin JS. Risk factors for relapse of ventilator-associated pneumonia in trauma patients. J Trauma 67: 91–96, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Scalfani MT, Chan DM, Murdoch EL, Kovacs EJ, White FA. Acute ethanol exposure combined with burn injury enhances IL-6 levels in the murine ileum. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31: 1731–1737, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schwaca MG, Somers SD. Thermal injury-induced immunosuppression in mice: the role of macrophage-derived reactive nitrogen intermediates. J Leukoc Biol 63: 51–58, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schwaca MG, Zhang Q, Rani M, Craig T, Oppeltz RF. Burn enhances toll-like receptor induced responses by circulating leukocytes. Int J Clin Exp Med 5: 136–144, 2012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schwarz BT, Wang F, Shen L, Clayburgh DR, Su L, Wang Y, Fu YX, Turner JR. LIGHT signals directly to intestinal epithelia to cause barrier dysfunction via cytoskeletal and endocytic mechanisms. Gastroenterology 132: 2383–2394, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shen L, Black ED, Witkowski ED, Lencer WI, Guerriero V, Schneeberger EE, Turner JR. Myosin light chain phosphorylation regulates barrier function by remodeling tight junction structure. J Cell Sci 119: 2095–2106, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Suenaert P, Bulteel V, Lemmens L, Noman M, Geypens B, Van Assche G, Geboes K, Ceuppens JL, Rutgeerts P. Anti tumor necrosis factor treatment restores the gut barrier in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 97: 2000–2004, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tang Y, Forsyth CB, Farhadi A, Rangan J, Jakate S, Shaikh M, Banan A, Fields JZ, Keshavarzian A. Nitric oxide-mediated intestinal injury is required for alcohol-induced gut leakiness and liver damage. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33: 1220–1230, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thal ER, Bost RO, Anderson RJ. Effects of alcohol and other drugs on traumatized patients. Arch Surg 120: 708–712, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tinsley JH, Teasdale NR, Yuan SY. Myosin light chain phosphorylation and pulmonary endothelial cell hyperpermeability in burns. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286: L841–L847, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tsukamoto T, Chanthaphavong RS, Pape HC. Current theories on the pathophysiology of multiple organ failure after trauma. Injury 41: 21–26, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Turner JR, Rill BK, Carlson SL, Carnes D, Kerner R, Mrsny RJ, Madara JL. Physiological regulation of epithelial tight junctions is associated with myosin light-chain phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 273: C1378–C1385, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Turner JR. Molecular basis of epithelial barrier regulation from basic mechanisms to clinical application. Am J Pathol 169: 1901–1909, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang F, Graham WV, Wang Y, Witkowski ED, Schwarz BT, Turner JR. Interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α synergize to induce intestinal barrier dysfunction by up-regulating myosin light chain kinase expression. Am J Pathol 166: 409–419, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang F, Schwarz BT, Graham WV, Wang Y, Su L, Clayburgh DR, Abraham C, Turner JR. IFN-γ-induced TNFR2 upregulation is required for TNF-dependent intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction. Gastroenterology 131: 1153–1163, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yang R, Han X, Uchiyama T, Watkins SK, Yaguchi A, Delude RL, Fink MP. IL-6 is essential for development of gut barrier dysfunction after hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 285: G621–G629, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zolotarevsky Y, Hecht G, Koutsouris A, Gonzalez DE, Quan C, Tom J, Mrsny RJ, Turner JR. A membrane-permeant peptide that inhibits MLC kinase restores barrier function in in vitro models of intestinal disease. Gastroenterology 123: 163–172, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]