Abstract

Background

Latinos are now the largest (and fastest growing) ethnic minority group in the United States. Latinas report high rates of physical inactivity and suffer disproportionately from obesity, diabetes, and other conditions that are associated with sedentary lifestyles. Effective physical activity interventions are urgently needed to address these health disparities.

Method/Design

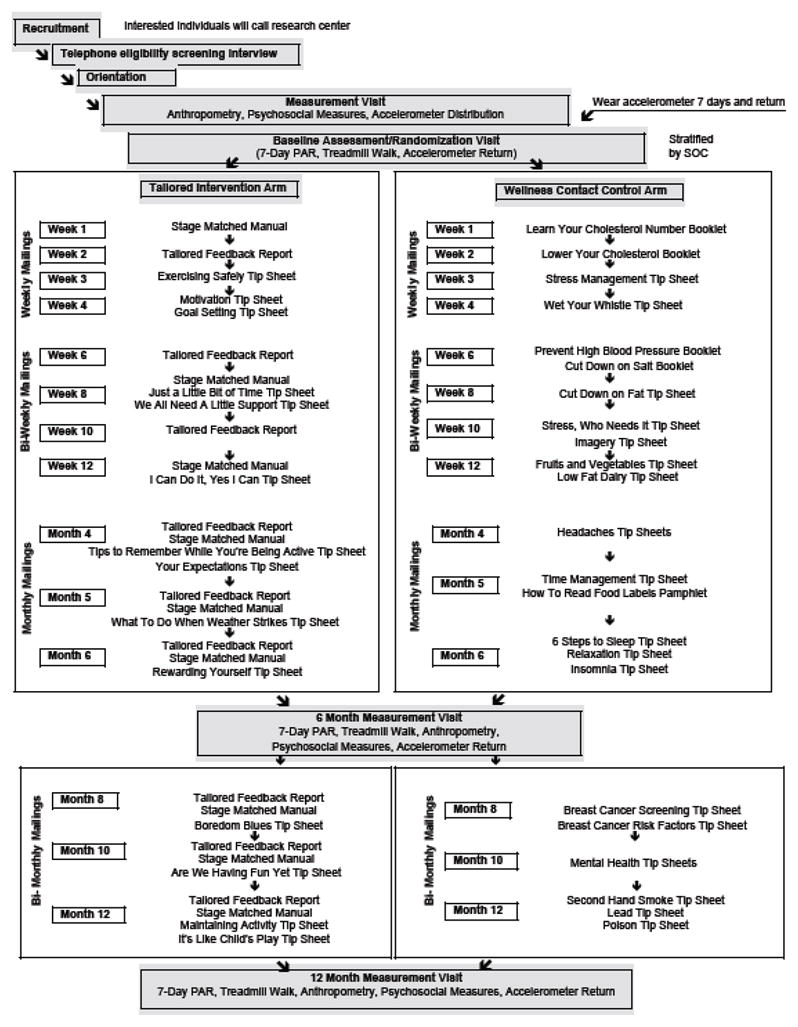

An ongoing randomized controlled trial will test the efficacy of a home-based, individually tailored physical activity print intervention for Latinas (1R01NR011295). This program was culturally and linguistically adapted for the target population through extensive formative research (6 focus groups, 25 cognitive interviews, iterative translation process). This participant feedback was used to inform intervention development. Then, 268 sedentary Latinas were randomly assigned to receive either the Tailored Intervention or the Wellness Contact Control arm. The intervention, based on Social Cognitive Theory and the Transtheoretical Model, consists of six months of regular mailings of motivation-matched physical activity manuals and tip sheets and individually tailored feedback reports generated by a computer expert system, followed by a tapered dose of mailings during the second six months (maintenance phase). The main outcome is change in minutes/week of physical activity at six months and one year as measured by the 7-Day Physical Activity Recall (7-Day PAR). To validate these findings, accelerometer data will be collected at the same time points.

Discussion

High reach, low cost, culturally relevant interventions to encourage physical activity among Latinas could help reduce health disparities and thus have a substantial positive impact on public health.

Keywords: physical activity, exercise, health disparities, Latinas, Hispanics

Introduction

Regular physical activity can help control weight and reduce the risk of developing diabetes, hypertension, colon and breast cancer, and cardiovascular disease [1]. Despite these health benefits, Latinos in the U.S., especially women, report high rates of sedentary lifestyle (53.4% vs. 35.3% for Non-Hispanic Whites) and are disproportionately burdened by related medical conditions (cancer, diabetes, hypertension) [2]. Due to cultural factors, socioeconomic circumstances, differences in educational background, and language barriers, Latinas may have limited access to public health interventions that promote active lifestyles. For example, while the Latino population is rapidly increasing and now represents the largest minority group in the U.S., most physical activity programs and resources in the U.S. are provided in English and thus may be difficult to navigate for Spanish-only speaking individuals. Effective physical activity interventions that are tailored to the needs of Latinas and leverage state-of-the-art theory and methods are needed to address existing health disparities.

Several recent physical activity intervention studies have been conducted with Latinas. The Arizona WISEWOMAN project involved randomly assigning 217 uninsured, primarily Latino (75%) women over the age of 50 to: 1) provider (nurse practitioner) counseling on increasing physical activity and consumption of fruits and vegetables, 2) provider counseling and health education, or 3) provider counseling, health education, and community health worker support [3]. At one year, all participants reported significant increases in weekly minutes of physical activity. While the authors did not reference any attempts at culturally adapting this intervention, the community health workers were bilingual and all interviews were conducted in English or Spanish, depending on participant preference. A study with 151 low-income Latinas [4] provided three merengue/salsa sessions per week over six months at a “store-front” exercise site near a community clinic, which produced significant increases in self-reported vigorous exercise and fitness at posttest, in comparison to the safety education control condition. In another study, 25 low-income Spanish-speakers (80% women) with type 2 diabetes were offered ten diabetes self-management group sessions [5]. Culturally sensitive components included inviting family members to participate, using culturally popular activities (e.g., a soap opera) to teach, including social activities (e.g., coffee time before session), and delivering the intervention in participants’ preferred language. At six months, results indicated a trend toward increased physical activity in the intervention group, compared to the control (p=.11).

To date, most interventions in this at risk group have been center-based, necessitating frequent clinic visits. Latinas often cite family and job responsibilities that might interfere with their ability to participate in such programs [6]. Our past research has shown that computer expert system-driven, individually tailored, theory-based (Social Cognitive Theory and Transtheoretical Model) [7, 8] interventions can produce significant increases in physical activity levels in Non-Hispanic predominately White samples [9–13]. Such interventions can be delivered through the mail and overcome the previously described barriers by allowing Latinas to participate from home when the time is convenient. This study is designed to test the efficacy of a 6-month culturally and linguistically adapted, computer-tailored physical activity intervention for Latinas. This paper describes the design, rationale, and baseline findings from this randomized controlled trial.

Methods

Design

The Seamos Saludables study is a randomized controlled trial (N=268) of a 6-month culturally and linguistically adapted, individually-tailored physical activity print intervention for Latinas vs. a wellness contact control condition. The main dependent variable is self-reported physical activity per week at baseline and six months as measured by the 7-Day Physical Activity Recall (7-Day PAR). Our hypothesis is that the culturally and linguistically adapted physical activity intervention will produce significantly greater increases in physical activity participation from baseline to post-intervention (six months) among a Latina sample than the wellness contact control condition. Secondary aims include examining maintenance of behavior change at 12 months post-randomization, corroborating self-report physical activity findings with accelerometer data from these three time points (baseline, six months, twelve months), and exploring potential mediators (e.g., self-efficacy, cognitive and behavioral processes of change, theoretical constructs specifically targeted by the physical activity intervention) and moderators (baseline stage of change and environmental access to physical activity equipment) of treatment effects.

As effective health interventions must be consistent with the shared beliefs, values, and practices of the target population, we conducted a series of formative research to culturally and linguistically adapt the existing empirically supported, home-based, individually-tailored physical activity intervention for Latinas prior to the current study. While this program has been delivered with success via the Internet, telephone, and mailed print materials in past studies with mostly White participants, during our formative research with Latinas, the women indicated a preference for receiving physical activity information through mail-delivered print materials. Telephone contact was described as potentially disruptive to family time and many women expressed concerns regarding lack of Internet access. Six focus groups were conducted to identify culture-specific attitudes and barriers to physical activity for Latinas. Themes were incorporated into the intervention text and included balancing caregiver/household responsibilities, cultural norms about self-sacrifice, social support, partner negotiation, and dealing with inclement weather and neighborhood safety (see table 1). For example, women were encouraged to fit physical activity into their busy schedules and provided with suggestions (e.g., walking during lunch break) that did not interfere with household responsibilities (e.g., cooking dinner for family). Please see table 1 for more examples of how feedback from participants was incorporated into the intervention development process.

Table 1.

Themes From Focus Groups & Literature Review And Resulting Modifications

| Theme | Intervention Modification |

|---|---|

| Literacy | Used qualitative methods and low-literacy strategies to modify measures and materials to better match our sample’s educational experience. |

| Daily Stressors/Negative Mood | Added more information on mood benefits of physical activity and strategies for activity initiation when in negative mood (e.g., small goal setting, social support, linking physical activity to pleasurable activities). |

| Neighborhood Safety | Added safety recommendations (exercise indoors or in well-lit public areas with partners). |

| Lack of Time | Augmented existing content on this topic with examples that are familiar to Latinas (working around children’s and household schedules). |

| Lack of Motivation | Added language that is familiar to Latinas (e.g., “falta de ganas”). |

| Childcare/Concern with Child Welfare | Discussed how physical activity can improve child welfare (i.e., increases energy to care for children and sets good example). |

| Partner Support | Added text from the marital therapy field on partner negotiation. |

| Personal Empowerment | Discussed benefits of self-care to individual and others and how to attend to one’s own needs in the face of conflicting demands from others. |

| Not Having Money for Fitness | Reframed physical activity to include behaviors that do not require gym membership or special equipment (i.e., walking or dancing). |

| Inclement Weather | Added text on winter options for physical activity as well as suggestions for appropriate winter clothing. |

| Gender roles | Discussed how women get many benefits from regular activity, examples of fit Latina celebrities, and concerns regarding sweating |

| Different Body Size Ideals | Emphasized that fitness does not mean “losing your curves.” |

All research measures and materials were translated into Spanish (and back-translated). 25 cognitive interviews were conducted to improve the clarity of the intervention and assessment text and ensure that key messages were not lost in translation. For example, “physical activity” appeared to be broadly defined by our participants and could include various activities of daily living (such as picking up children from school). However, “exercise” had the desired connotation (purposeful, moderate intensity or greater physical activity). Therefore this term was used consistently in our current study’s intervention and assessment efforts. Modifications also included changing references to “rewarding yourself for meeting exercise goals” to “doing something nice for yourself”, to avoid a materialistic connotation that might not be appropriate or realistic considering the income level of many participants.

Once program modifications were made based upon participant feedback, a small single-arm demonstration trial (N=12) and pilot randomized trial (N=93) were conducted to assess the feasibility and acceptability of this home-based approach to promoting physical activity in Latinas [14]. Promising preliminary findings called for further investigation and led to the current randomized controlled trial.

Setting and Sample

The study was conducted at a research center affiliated with the Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Human subjects’ approval was obtained from the Brown University Institutional Review Board. The sample was comprised of women recruited from the Rhode Island/Southern Massachusetts area who self-identified as Hispanic or Latina (or of a group defined as Hispanic/Latino by the Census Bureau). See table 2 for sample characteristics.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics (N=268)

| Characteristics | Intervention (M and SD or %) | Control (M and SD or %) | Overall (M and SD or %) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Latina | 100% | 100% | 100% |

|

| |||

| Age | 41.56 (10.04) | 39.61 (9.95) | 40.58 (10.02) |

|

| |||

| Generational status | |||

| First | 90.23% | 96.30% | 93.28% |

| Second/Third* | 9.77% | 3.70% | 6.72% |

|

| |||

| Speak only Spanish/More Spanish than English at home | 79.70% | 83.70% | 81.72% |

|

| |||

| Country of Origin | |||

| Puerto Rico | 11.28% | 10.45% | 10.86% |

| Dominican Republic | 33.83% | 41.04% | 37.45% |

| Mexico | 5.26% | 4.48% | 4.87% |

| Guatemala | 6.77% | 11.19% | 8.99% |

| Colombia | 30.08% | 21.64% | 25.84% |

| Other | 12.78% | 11.19% | 11.99% |

|

| |||

| Educational level | |||

| ≤High school graduate | 43.61% | 46.67% | 45.15% |

| Some college | 32.33% | 32.59% | 32.46% |

| College graduate or more | 24.06% | 20.74% | 22.39% |

|

| |||

| Employment Status | |||

| Unemployed | 46.21% | 48.51% | 47.37% |

| Full time | 36.36% | 24.63% | 30.45% |

| Part time | 17.42% | 24.63% | 21.05% |

| Don’t know | 0 | 2.23% | 1.13% |

|

| |||

| Yearly household income | |||

| < $10,000 | 25.00% | 26.56% | 25.78% |

| ≥$10,000 but <$20,000 | 27.34% | 28.12% | 27.73% |

| ≥ $20,000 but <$30,000 | 14.84% | 15.63% | 15.23% |

| ≥ $30,000 but <$40,000 | 10.94% | 6.25% | 8.59% |

| $40,000+ | 13.28% | 8.59% | 10.94% |

| Do Not Know | 8.59% | 14.84% | 11.72% |

|

| |||

| Marital status | |||

| Married/living with partner | 62.41% | 52.24% | 57.30% |

| Single | 10.53% | 16.42% | 13.48% |

| Divorced | 15.79% | 11.19% | 13.48% |

| Separated | 10.43% | 18.66% | 14.61% |

| Widowed | 0.75% | 1.49% | 1.12% |

|

| |||

| BMI | 29.61 (4.33) | 29.23 (5.02) | 29.42 (4.69) |

|

| |||

| Waist Measured in Inches | 34.84(4.38) | 34.16(4.69) | 34.50(4.54) |

|

| |||

| Hips Measured in Inches | 42.21(3.48) | 41.82(4.04) | 42.01(3.77) |

|

| |||

| Systolic Blood Pressure* | 116.57(11.19) | 119.93(10.73) | 118.26(11.07) |

|

| |||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure* | 72.91(8.50) | 75.81(8.12) | 74.37(8.42) |

|

| |||

| Body Fat % | 38.38(5.99) | 38.38(6.47) | 38.38(6.23) |

|

| |||

| Health Literacy (scores of 23–36 “adequate”) | 31.82 (5.18) | 31.82 (5.35) | 31.81 (5.26) |

indicates significant group differences, p>.05

Recruitment

Recruitment involved advertising in local newspapers with Latina readership and local Spanish-language radio and television stations. Flyers inviting individuals to participate in a research study and help us learn how to help Latinas become healthier were placed in public areas such as grocery stores with high traffic of Latinas. Other recruitment methods include attendance at local Latino churches, cultural festivals and other events; advertisements on listserves and Internet sites such as Craig’s List; and letters to participants of the pilot study. Finally, a referral “voucher” incentive program was used to encourage participants to refer friends or relatives after completing the study.

Screening and Eligibility Requirements

Interested individuals responding to our advertisements called the research center and completed a telephone screening interview to determine initial eligibility. To be eligible, potential participants needed to be underactive, defined as participating in moderate or vigorous physical activity two days per week or less for 30 minutes or less each day, and deny any history of coronary heart disease (history of myocardial infarction or symptoms of angina), diabetes, stroke, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, orthopedic problems, or any other serious medical condition that would make physical activity unsafe.

To reduce the likelihood of adverse events, participants were screened to identify physiological factors that could potentially increase risk of injury. A telephone screener version of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) was used to assess cardiovascular and musculoskeletal risk factors. The PAR-Q is recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine for physical activity at moderate intensity [15]. Any individual that was positive for an item on the PAR-Q was ineligible for participation. If the individual was negative for all items on PAR-Q but disclosed a medical condition or situation that could possibly interfere with physical activity behavior, physician clearance was required prior to enrollment in the study. The study physician provided guidance and counsel regarding medical questions that arose when screening for eligibility.

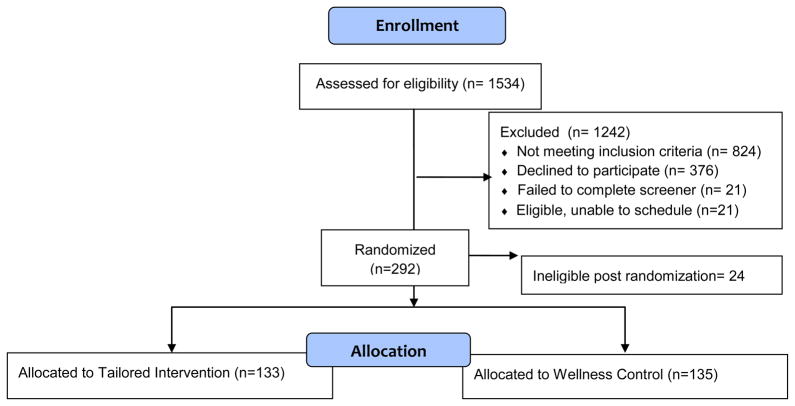

Other exclusion criteria included current or planned pregnancy, planning to move from the area within the next twelve months, hospitalization due to a psychiatric disorder in the past 3 years, BMI above 45, and/or taking medication that may impair physical activity tolerance or performance (e.g., beta blockers). Participants in the study also had to be between the ages of 18–65 and willing to be randomly assigned to one of the two intervention conditions. If a person met eligibility criteria based on this interview, they were scheduled for an orientation session. See figure 1 for study schema.

Figure 1.

Study Schema

Protocol

Orientation Session

After the telephone screening interview, participants attended an in-person orientation session to obtain more information about the study. Bilingual/bicultural research staff gave a power point presentation describing the study and rights of participation and answered questions from the participants. Individuals who remained interested in participation signed the informed consent document, filled out questionnaires regarding demographic characteristics and health literacy, and were given a packet of questionnaires on physical activity-related psychosocial variables (stages and processes of change, self-efficacy, enjoyment, social support, depression, environmental access) to complete prior to the next session.

Measurement Session

The measurement visit involved anthropometric measures (i.e., height, weight, waist and hip circumference, blood pressure, percent body fat). Body weight and composition were measured with participants wearing an examining gown. A calibrated Health-O-meter medical scale and Seca stadiometer were utilized to measure body weight (to the quarter pound) and height (to the quarter inch). A Quantum II bioelectrical body composition analyzer (RJL Systems, Inc., Detroit, MI), a four-electrode system that determines resistance and reactance, was used to conduct body impedance measurement, along with the Segal equation [16] for determining percent body fat. Waist and hip circumference were obtained using the largest circumference of the posterior extension of the buttocks and smallest circumference of the torso (natural waist) [17]. A sitting blood pressure was obtained using a mercury sphygmomanometer. Participants with initial readings greater than > 140 systolic and/or >90 diastolic were asked to rest and repeat the measurement 10 minutes later. If the blood pressure remained elevated but was ≤ 160 systolic and/or ≤ 100 diastolic and the subject has no known history of high blood pressure, the participant required physician clearance in order to participate. If the blood pressure was >160 systolic and/or >100 diastolic, the person was not eligible to participate. At this visit, participants also received ActiGraph GT3X accelerometers, with instructions to wear the accelerometer during waking hours for 7 consecutive days.

Baseline Assessment/Randomization Session

One week following the measurement visit, participants returned the accelerometer and completed psychosocial measures. Prior to the 7-Day Physical Activity Recall interview, all participants underwent a 10-minute treadmill walk to demonstrate moderate intensity physical activity. Two research staff members with up-to-date CPR/AED-training were present during the treadmill walk to assist in case of an emergency. The goal of this protocol was to help improve accuracy of self report by providing a live, experiential demonstration of a 10 minute bout of moderate intensity physical activity. Participants were then assigned to one of two Spanish-language print-based mail-delivered intervention conditions: tailored intervention or wellness contact control. Group assignment was determined by a list of random numbers, which was stratified by stage of change to ensure an equal distribution of the different levels of motivational readiness for physical activity across groups.

Once participants were randomized to group, the wellness contact control group received nutritional information. The intervention group was given handouts regarding national guidelines for physical activity and the study goal of at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity aerobic physical activity per week. Intervention participants also selected realistic, achievable activity goals that could be gradually increased until the national guidelines were reached. Research staff helped to problem-solve anticipated barriers to physical activity, using materials focused on barriers and attitudes frequently reported by Latinas according to a comprehensive literature review, formative research, and a qualitative analyses of pilot data.

Intervention participants were also given information on local physical activity resources (e.g., nearby scenic walking paths, free/low cost aerobics and dance classes), Omron HJ-720ITC Go Smart pedometers, and 12 physical activity logs. The activity logs involved tracking total minutes of moderate intensity or greater physical activity and whether a pedometer was worn each day. Participants were encouraged to mail the completed monthly logs back to the research center at the end of each month. To promote self monitoring of physical activity behavior, research staff mailed a $10 gift certificate to participants for each returned activity log and contacted participants by telephone when monthly logs were not received in a timely fashion.

All participants receive regular mailings of group-appropriate health educational materials over six months (i.e., four mailings in month 1, two mailings in months 2–3, and one mailing in months 4–6, with booster mailings in months 8, 10, 12; see Intervention and Wellness Contact Control Condition subsections below for more details). Participants then return to the research center for assessments at 6 and 12 months.

Six and twelve month assessment sessions

Six month and twelve month assessment sessions are ongoing. Participants are mailed ActiGraph accelerometers with instructions to wear them for 7 days prior to both visits. At both follow-up sessions, participants return the accelerometers and complete anthropometric and psychosocial measures, a 10-minute treadmill walk, and the 7-Day Physical Activity Recall interview again. At 12 months, participants also complete a consumer satisfaction questionnaire and a subsample will be asked to undergo qualitative in-depth interviews to explore participants’ overall perceptions and satisfaction with the intervention. Suggestions for program improvement will be solicited.

Measures

To control for contact time, assessments were administered to both groups. The baseline assessments have been completed. Six and twelve month assessments are still taking place at the research center, while the ongoing monthly psychosocial assessments are completed by mail. Assessments are conducted to examine the efficacy of the intervention as well as to provide data for the computer expert system to use in generating tailored physical activity counseling messages for the intervention group.

Demographics were assessed at baseline with a brief questionnaire regarding age, education, income, occupation, race, ethnicity, history of residence, and marital status. The Brief Acculturation Scale (BrAS) is a four-item measure that asks about language use across different life contexts (i.e., at home, with friends). The BrAS has good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha=.90) and correlates highly with generational status, time in country, and ethnic identity [18]. The Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (STOFHLA), a brief (7-minute) measure designed to evaluate adult literacy in the health care setting, was also administered [19] .

The 7-Day Physical Activity Recall serves as the primary outcome measure [20, 21]. The 7-Day PAR is an interviewer-administered instrument that provides an estimate of weekly minutes of physical activity and uses multiple strategies for increasing accuracy of recall, such as breaking down the week into daily segments (i.e., morning, afternoon, and evening) and asking about many types of activities, including time spent sleeping and in moderate, hard, and very hard activity. The 7-Day PAR has been used across many studies of physical activity and has consistently demonstrated acceptable reliability, internal consistency, and congruent validity with other more objective measures of activity levels [22–30]. Past research indicates that the 7-Day PAR is sensitive to changes in moderate intensity physical activity over time [31, 32] and has good test-retest reliability among Latino participants [33].

Prior to conducting these interviews for study purposes, research assistants underwent rigorous training on the administration of the 7-Day PAR with a research staff member, who was professionally trained by the Cooper Institute and has completed over three thousand 7-Day PARs. The trainer administered the 7-Day PAR interview to both research assistants and then had them observe her conduct the 7-Day PAR with two research participants from another physical activity study and listen to four audio-taped trainer-administered interviews. Finally, the research assistants conducted two 7-Day PAR interviews under the trainer’s direct supervision and received feedback from the trainer on four audio-taped interviews conducted with volunteers. To encourage adherence to protocol and reliability between research assistants, all interviews were audio-taped and 20% of the interviews were reviewed by a bilingual/bicultural Ph.D. level Investigator at another institution. Feedback and suggestions for improvement were provided in person and/or by telephone as needed.

To corroborate the self-report 7-Day PAR data, participants also wore ActiGraph accelerometers for seven days prior to the baseline assessment (overlapping with the 7-Day PAR recall period). Accelerometers measure both movement and intensity of activity and have been validated with heart rate telemetry [34] and total energy expenditure [35]. Accelerometer data was processed using the ActiLife 5 software, with a cutpoint of 1952 to establish the minimum threshold for moderate intensity activity. To be counted in the total minutes/week of activity, activity had to occur in 10 minute bouts. We assessed whether there were any statistical outliers and reported median activity at baseline, as medians are less impacted by potential outlying values (compared to means).

Psychosocial measures related to depression, social support, and physical activity enjoyment and environment were also completed. The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 10-question measure of depressive symptoms [36] that has been translated and validated across different ethnic groups, with internal consistencies of .87 and above in both English and Spanish [37–39]. Social support for physical activity was examined in terms of support from friends and family members for physical activity. The 13-question measure has three subscales with acceptable internal consistencies (alphas range from 0.61 to 0.91) and good criterion validity [40]. The Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) [41] assesses the level of personal satisfaction derived from physical activity participation. The measure has 18 items with high internal consistency (alpha = 0.96) and criterion validity [41]. Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale, Abbreviated (NEWS-A) includes 54 items [42, 43] assessing various aspects of the built environment related to walking, neighborhood aesthetics, and traffic. Several studies have supported the test–retest reliability of the NEWS [44–46], as well as its construct validity by reporting significant differences on some NEWS subscales between neighborhoods selected to differ on walkability [45, 46] and modest correlations between NEWS subscales and accelerometer [47] and self-reported [48] estimates of physical activity.

Three measures, stage of change, self-efficacy for physical activity, and the processes of change, were administered at baseline and on a monthly basis via mail and used to help generate the tailored expert system feedback reports for the intervention group. The 4-item stage of change measure has demonstrated reliability (Kappa = 0.78; intra-class correlation r = 0.84) as well as shown acceptable concurrent validity with measures of self-efficacy and current activity levels [49]. The 40-item processes measure contains 10 sub-scales that address a variety of processes of activity behavior change. Internal consistency of the sub-scales ranged from .62 to .96 [50]. Self-efficacy, or confidence in one’s ability to persist with exercising in various situations, such as when feeling fatigued or encountering inclement weather, was measured with a 5-item instrument [49] developed by Marcus and colleagues (alpha = .82).

Tailored Intervention

The intervention is based on the Social Cognitive Theory and the Transtheoretical Model, emphasizes behavioral strategies for increasing activity levels (i.e., goal-setting, self-monitoring, problem-solving barriers, increasing social support, rewarding oneself for meeting physical activity goals), and includes regular mailings (see figure 1) of physical activity manuals matched to the participant’s current motivational readiness for physical activity and individually tailored feedback reports generated by a computer expert system that address the thoughts, feelings, and concerns identified by the participants in their monthly questionnaires. These individually tailored reports draw particular messages from a library of approximately 296 messages regarding motivation (e.g., “Your answers to exercise survey show that you are ready to begin exercising regularly. You are no longer just thinking about it, but you have already taken steps to become more active. Congratulations!), self-efficacy (e.g., “Although you are not very active, you seem confident about your ability to exercise. This is a good sign! For many people, trying to fit in some exercise on top of the demands of work and family can be a real challenge. Try making time for a ten minute walk one or two days this week.. It will help you continue to build your confidence about your ability to fit exercise into your lifestyle.”), and cognitive and behavioral strategies for physical activity adoption (e.g., “You’ve been using reminders to help you think about exercising. This is great! Doing these kind of things, like leaving yourself notes to exercise, or bringing walking shoes to work can be very helpful.”) based on participants’ responses to questionnaires. In addition, the expert system provides normative feedback on how the participant compares to profiles of individuals who have successfully adopted and maintained physical activity along. It also provides feedback regarding individual progress to date in terms of physical activity participation and associated process variables. General information tip-sheets on topics such as stretching were also provided. Please see Table 1 for an outline of physical activity barriers and intervention needs and preferences specific to Latinas (identified through a comprehensive literature review and our formative research) and our efforts to address these factors in all components of the intervention.

Quality Control

Bilingual research assistants audited 10% of tailored reports for quality control. After hand-scoring the original data and comparing these results to normative scores and prior results obtained from that participant, auditors reviewed the reports and determined if the expert system selected the correct content. This system allows for early detection and correction of errors in the programming of the expert system.

Intervention Fidelity

The intervention fidelity protocol for the current study involves 1) following up on any returned intervention mailings (calling participants to confirm address, verifying address on envelope and in tracking system); 2) updating participant contact information at each point of contact; 3) asking participants in consumer satisfaction questionnaires to what degree the intervention was received, read, and enacted; 4) having participants log their daily physical activity and mail these logs back to the research center each month; 5) calling participants with late/unsent physical activity logs to see if intervention materials are being received/read and problem solve any issues that may have arisen.

Wellness Contact Control Condition

The attention control condition received health information on topics other than physical activity, including bilingual pamphlets on heart-healthy behaviors developed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) for Latinos [51]. The pamphlets focus on diet and other factors associated with cardiovascular disease risk (e.g., smoking) and were specifically targeted to Latinos with low levels of acculturation, ages 18 to 54, low socio-economic status, and low education.

Improving Treatment Retention

Numerous steps are taken in Seamos Saludables to minimize obstacles to research participation such as cost, childcare, and transportation. The intervention is provided free of charge and delivered via mail. In addition, we provide $10 gas cards to help cover transportation expenses related to assessment visits. Taxi vouchers and bus tokens are given to the women who do not have their own transportation. Participants are reimbursed for childcare during visits to the research center. If participants cannot arrange for childcare, research staff encourage them to bring the child with them to the session. Participants are compensated for their time and receive $25 gift cards for attending six months and twelve months assessments plus a $50 bonus for attending both visits. Participants are also paid $10 each month for filling out the packet of psychosocial measures used to tailor feedback reports and mailing them back to the research center. Light snacks are provided at orientation and assessment sessions.

Power Analysis

Power analysis calculations were based on results of the pilot study (R21 NR009864) indicating a mean change in moderate intensity or greater physical activity following the intervention of 75.82 minutes/week (SD=70.43) from baseline to 3 months versus 51.73 minutes/week (SD=80.97) among controls. As the current study will run longer, we expect to see more substantial differences between the treatment arms at 6 months, as in previous studies [12, 52]. Thus, with a sample size of 268, we expect to have 74% power to detect similar differences in physical activity minutes between the intervention and control arms at end of treatment (6 months), using a two-tailed significance level α=0.05. We anticipate that retention rates in the current study will be similar to those observed in the pilot (7% attrition at 3 months) and plan to use the same imputation scheme as was used with the pilot data; thus, no further adjustment has been made for the attrition rates. This sample size was deliberately conservative as it does not assume the availability of repeated outcome measures that will be taken throughout the study. By choosing models that make use of the longitudinal data, we will be increasing the power to detect differences between treatment arms.

Proposed Analyses of Main Outcomes

The analysis plan includes 1) examination of distribution of primary outcome variables and transformations towards normality and to reduce the effect of outliers, when appropriate, 2) examination of the effectiveness of the randomization procedure across demographic and psychosocial variables, and 3) a longitudinal regression model, implemented using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with robust standard errors, to simultaneously test differences between treatment conditions on both the primary outcome (6-month data) and secondary outcome (maintenance at 12 months), while adjusting for potential confounders of the treatment effect and any variables not balanced by randomization. The strength of the association between the 7-Day PAR and Actigraph measures will be estimated using spearman rank order correlations, which are less sensitive to extreme values. Regression analyses will be conducted to examine potential mediators and moderators.

Results

1534 individuals expressed interest in participation by contacting the research center. However, most did not meet eligibility criteria (n=824), whereas others declined to participate (n=376), failed to complete the eligibility screener (n=21), or were eligible but not able to be scheduled (n=21). The sample included the remaining 268 women randomly assigned to the Intervention (N=133) and Wellness Contact Control (N=135) arms, as 24 participants were deemed ineligible post-randomization. Overall the sample is comprised of mostly overweight, sedentary Latinas with low levels of income and acculturation. Approximately 93% are first generation immigrants to the U.S. (mostly from the Dominican Republic and Colombia) and 82% of participants speak only Spanish or more Spanish than English at home. Most participants reported an annual household income < $30,000 (69%) and 45% have < a high school education. Participants, on average, had adequate functional health literacy (M score=31.81, SD= 5.26; with scores between 23–36 categorized as adequate) and 28% of the sample reported “significant” or “mild” depressive symptomatology (scores > 11 on the CES-D). The average age was 40.58 years old (SD=10.02). There were no group differences in psychosocial variables at the baseline assessment, except significantly lower blood pressure levels and a significantly higher percentage of participants reported being born in the U.S. in the intervention vs. control arm.

Participants reported low levels of physical activity and related psychosocial process variables at baseline assessment. The median minutes per week of at least moderate intensity physical activity at baseline was 0. We hypothesize that a recently adopted, 10 minute, supervised, moderate intensity (3–4 mph) treadmill walk protocol may be partially responsible for such self report findings, which are similar to another study [53] in which we included the treadmill walk and substantially lower than those found in studies prior to the adoption of this protocol [54]. Moreover, the baseline self report physical activity levels (7-Day Physical Activity Recall) were significantly correlated with more objective accelerometer data (based on Spearman Correlation). Specifically, rho=0.26, p<.01. Participants reported correspondingly low motivational readiness for physical activity (94% in Contemplation), self-efficacy, cognitive and behavioral processes of change, social support from family and friends, and enjoyment of physical activity (see Table 3). However, according to NEWS-A scores, most participants reported finding their neighborhoods reasonably walkable, when queried on factors such as street connectivity, safety, and aesthetics.

Table 3.

Baseline Physical Activity Levels and Related Psychosocial Variables (N=268)

| Variables | Intervention | Control | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Self report (≥ moderate intensity) physical activity (minutes/week, N=258, 7-Day PAR) | Median=0 | Median=0 | Median=0 |

|

| |||

| Accelerometer measured physical activity (minutes/week, N=259)* | Median=0 | Median=0 | Median=0 |

|

| |||

| Depression (scores ≥ 11 indicative of depression) | 7.72 (6.07) | 7.60 (5.99) | 7.66 (6.02) |

|

| |||

| Self-Efficacy (range = 1–5) | 2.19 (0.81) | 2.14 (0.76) | 2.17 (0.79) |

|

| |||

| Enjoyment (range = 18–126) | 86.98 (23.59) | 83.25(22.16) | 85.10 (22.91) |

|

| |||

| Behavioral Processes (range = 1–5) | 2.00 (0.63) | 2.01 (0.64) | 2.00 (0.63) |

|

| |||

| Cognitive Processes (range = 1–5) | 2.53 (0.82) | 2.48 (0.83) | 2.51 (0.83) |

|

| |||

| Stage of Change | |||

| Precontemplation | 2.26% | 2.96% | 2.61% |

| Contemplation | 93.98% | 93.33% | 93.66% |

| Preparation | 3.76% | 3.70% | 3.73% |

|

| |||

| Social Support | |||

| Friends (range =10–50) | 15.26 (6.43) | 15.43 (6.13) | 15.35 (6.27) |

| Family (range = 10–50) | 17.35 (7.14) | 16.48 (6.49) | 16.91 (6.82) |

| Reward & Punishment (range = 3–15) | 3.33 (0.84) | 3.40 (1.01) | 3.37 (0.93) |

|

| |||

| NEWS (N ranges 266 to 268) | |||

| Residential Density (range = 173–865) | 244.52 (64.35) | 244.43 (78.11) | 244.47 (71.53) |

| Land-use Mix Diversity (range = 1–5) | 2.97 (0.92) | 2.98 (0.95) | 2.98 (0.94) |

| Land-use Mix Access (range = 1–4) | 3.20 (0.71) | 3.15 (0.74) | 3.17 (0.73) |

| Street Connectivity (range = 1–4) | 2.97 (0.81) | 3.02 (0.80) | 2.99 (0.80) |

| Infrastructure/Safety (range = 1–4) | 2.49 (0.69) | 2.43 (0.61) | 2.46 (0.65) |

| Aesthetics (range = 1–4) | 2.54 (0.90) | 2.42 (0.83) | 2.48 (0.87) |

| Traffic Hazards (range = 1–4) | 2.29 (0.73) | 2.27 (0.66) | 2.28 (0.70) |

| Crime (range = 1–4) | 1.86 (0.84) | 1.83 (0.91) | 1.84 (0.87) |

| Lack of Parking (range = 1–4) | 2.26 (1.17) | 2.24 (1.15) | 2.25 (1.16) |

| Lack of Cul de Sac (range = 1–4) | 2.88 (1.20) | 2.90 (1.27) | 2.89 (1.23) |

| Hilliness (range = 1–4) | 1.56 (0.94) | 1.67 (0.98) | 1.62 (0.96) |

| Physical Barriers (range = 1–4) | 1.45 (0.88) | 1.51 (0.97) | 1.48 (0.93) |

Scores of 0 indicate no physical activity (not missing data) or activity that did not occur in 10 minutes bouts.

Discussion

Baseline data from the Seamos Saludables study reflect national statistics [2] and confirm that this sample is in great need of intervention due to high rates of overweight and obesity and low levels of physical activity. However, associated process variables suggest they will be a challenging group. For example, participants reported particularly low motivational readiness and confidence to adopt physical activity, as well as little enjoyment or social support for such efforts. Small amounts of external reinforcement for completing intervention tasks ($5–10 per month for filling out psychosocial measures and monthly activity logs, like in the current study), if gradually faded out, may help encourage such participants to adopt the health behavior long enough to find it internally reinforcing (perhaps start to notice increased energy), without being coercive or potentially beyond the means of community organizations implementing this intervention.

The current study tests the efficacy of a culturally relevant home-based physical activity intervention for Latinas who may have difficulty attending clinic visits due to family or work responsibilities. The low cost, high reach technology-driven strategies used in the current study have great potential for adoption on a larger scale, thereby benefiting public health and eliminating health disparities. Furthermore, the Seamos Saludables program was provided in Spanish (as preferred by our sample and participants from a similar past study [3] in this area) and geared through formative research specifically to the physical activity intervention needs and preferences of Latinas and thus is likely to have a strong impact on this important health behavior. Lessons learned during this process include increased appreciation for the heterogeneity of the Latino population (which is comprised of numerous countries of origin, especially in New England) and complexity of the Spanish language. As for limitations, our sample is comprised of Hispanic/Latina women and community volunteers; thus results from this trial will not necessarily generalize to other groups. Furthermore, given that we measured natural waist, it is possible that our findings for waist measurement will not be comparable or normed with studies that utilize waist circumference, which is measured precisely between the hip bone and lowest rib.

Interestingly, while the original formative research conducted for the current study indicated that Latinas preferred receiving physical activity information via mail-delivered print materials, rather than through other home-based delivery channels (telephone, Internet), more recent data indicate that the Internet may be a more favorable and appropriate delivery channel for reaching this rapidly growing target population due to greater potential for interactivity, immediacy of feedback, and wider reach. 74.3% of the Seamos Saludables study participants reported having regular access to a computer with Internet for personal use, and 64.3% of these women now report wanting to receive physical activity advice and feedback over the web. Furthermore, participants have already begun spontaneously engaging in regular email communication regarding their physical activity with program staff, despite the print-based delivery channel for study materials in the current study.

There has been a recent increase in Internet use among Latinos, according to national statistics. Specifically, recent Pew Center data reveal that Internet use among Latino adults rose from 54% in 2006 to 64% in 2008. Access to the Internet among Latinos is also rapidly rising, with an estimated 44% having access in their homes in 2001 to nearly 65% in 2008 [55, 56]. The digital divide is shrinking; moreover, national surveys indicate that Latinos generally regard the Internet as an important source of information and are more trusting of the information they find online than other groups [57]. Thus to meet the changing intervention needs and preferences of this target population and capitalize upon the recent increases in Internet access and use among Latinos, future directions should include using interactive web-based technology to address the epidemic of sedentary lifestyle that has deleteriously and disproportionately impacted the health of this at risk group.

Figure 2.

Consort Diagram

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Susan Carton-Lopez, Raul Fortunet, Jane Wheeler, and Viveka Ayala-Heredia of Brown University for their valuable research assistance and contributions to this study, as well as Rachelle Edgar of University of California, San Diego for her valuable research assistance and help with figures and tables.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kinzie JD, Holmes JL, Arent J. Patients’ release of medical records: involuntary, uninformed consent? Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1985;36:843–7. doi: 10.1176/ps.36.8.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2007, with Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staten LK, Gregory-Mercado KY, Ranger-Moore J, Will JC, Giuliano AR, Ford ES, et al. Provider counseling, health education, and community health workers: the Arizona WISEWOMAN project. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004;13:547–56. doi: 10.1089/1540999041281133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hovell MF, Mulvihill MM, Buono MJ, Liles S, Schade DH, Washington TA, et al. Culturally tailored aerobic exercise intervention for low-income Latinas. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2008;22:155–63. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.22.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosal MC, Olendzki B, Reed GW, Gumieniak O, Scavron J, Ockene I. Diabetes self-management among low-income Spanish-speaking patients: A pilot study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;29:225–35. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2903_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harralson TL, Emig JC, Polansky M, Walker RE, Cruz JO, Garcia-Leeds C. Un Corazon Saludable: factors influencing outcomes of an exercise program designed to impact cardiac and metabolic risks among urban Latinas. J Community Health. 2007;32:401–12. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy, toward a more integrative model of change. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 1982;19:276–88. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcus BH, Banspach SW, Lefebvre RC, Rossi JS, Carleton RA, Abrams DB. Using the stages of change model to increase the adoption of physical activity among community participants. Am J Health Promot. 1992;6:424–9. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.6.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus BH, Bock BC, Pinto BM, Forsyth LH, Roberts MB, Traficante RM. Efficacy of an individualized, motivationally-tailored physical activity intervention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;20:174–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02884958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bock BC, Marcus BH, Pinto BM, Forsyth LH. Maintenance of physical activity following an individualized motivationally tailored intervention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;23:79–87. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2302_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcus BH, Napolitano MA, King AC, Lewis BA, Whiteley JA, Albrecht A, et al. Telephone versus print delivery of an individualized motivationally tailored physical activity intervention: Project STRIDE. Health Psychol. 2007;26:401–9. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcus BH, Lewis BA, Williams DM, Dunsiger S, Jakicic JM, Whiteley JA, et al. A comparison of Internet and print-based physical activity interventions. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:944–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pekmezi DW, Neighbors CJ, Lee CS, Gans KM, Bock BC, Morrow KM, et al. A culturally adapted physical activity intervention for Latinas: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37:495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. PAR-Q and you. Gloucester, Ontario: Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Segal KR, Gutin B, Presta E, Wang J, Van Itallie TB. Estimation of human body composition by electrical impedance methods: a comparative study. J Appl Physiol. 1985;58:1565–71. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.5.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callaway C, Chumlea W, Bouchard C, Himes J, Lohman T, Martin A, et al. Circumferences. In: Lohman T, Roche A, Martorelli R, editors. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Books; 1988. p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norris AE, Ford K, Bova CA. Psychometrics of a brief acculturation scale for Hispanics in a probability sample of urban Hispanic adolescents and young adults. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1995;10:537–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD, Fortmann SP, Rogers T, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1985;121:91–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blair SN, Haskell WL, Ho P, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Vranizan KM, Farquhar JW, et al. Assessment of habitual physical activity by a seven-day recall in a community survey and controlled experiments. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1985;122:794–804. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Gorber SC, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sloane R, Snyder DC, Demark-Wahnefried W, Lobach D, Kraus WE. Comparing the 7-day physical activity recall with a triaxial accelerometer for measuring time in exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1334–40. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181984fa8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayden-Wade HA, Coleman KJ, Sallis JF, Armstrong C. Validation of the telephone and in-person interview versions of the 7-day PAR. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:801–9. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000064941.43869.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irwin ML, Ainsworth BE, Conway JM. Estimation of energy expenditure from physical activity measures: Determinants of accuracy. Obesity Research. 2001;9:517–25. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson-Kozlow M, Sallis JF, Gilpin EA, Rock CL, Pierce JP. Comparative validation of the IPAQ and the 7-Day PAR among women diagnosed with breast cancer. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leenders NYJM, Sherman WM, Nagaraja HN, Kien CL. Evaluation of methods to assess physical activity in free-living conditions. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2001;33:1233–40. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leenders NYJM, Sherman WM, Nagaraja HN. Comparisons of four methods of estimating physical activity in adult women. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2000;32:1320–6. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200007000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pereira MA, FitzerGerald SJ, Gregg EW, Joswiak ML, Ryan WJ, Suminski RR, et al. A collection of Physical Activity Questionnaires for health-related research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:S1–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkinson S, Huang CM, Walker LO, Sterling BS, Kim M. Physical activity in low-income postpartum women. J Nurs Scholarship. 2004;36:109–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn AL, Garcia ME, Marcus BH, Kampert JB, Kohl HW, Blair SN. Six-month physical activity and fitness changes in Project Active, a randomized trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:1076–83. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199807000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunn AL, Marcus BH, Kampert JB, Garcia ME, Kohl HW, 3rd, Blair SN. Comparison of lifestyle and structured interventions to increase physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1999;281:327–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rauh MJ, Hovell MF, Hofsetter CR, Sallis JF, Gleghorn A. Reliability and validity of self-reported physical activity in Latinos. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1992;21:966–71. doi: 10.1093/ije/21.5.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janz KF. Validation of the CSA accelerometer for assessing children’s physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:369–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melanson EL, Jr, Freedson PS. Validity of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. (CSA) activity monitor. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:934–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen S, Herbert TB. Health psychology: psychological factors and physical disease from the perspective of human psychoneuroimmunology. Annual review of psychology. 1996;47:113–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D Scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Research. 1980;2:125–34. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia M, Marks G. Depressive symptomatology among Mexican-American adults: An examination with the CES-D Scale. Psychiatry Research. 1989;27:137–48. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guarnaccia PJ, Angel R, Worobey JL. The factor structure of the CES-D in the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: The influences of ethnicity, gender and language. Social Science & Medicine. 1989;29:85–94. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Preventive Medicine. 1987;16:825–36. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kendzierski D. Physical activity enjoyment scale: Two validation studies. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 1991;13:50–64. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Black JB, Chen D. Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: an environment scale evaluation. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1552–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cerin E, Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD. Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale: Validity and development of a short form. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2006;38:1682–91. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000227639.83607.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brownson RC, Chang JJ, Eyler AA, Ainsworth BE, Kirtland KA, Saelens BE, et al. Measuring the environment for friendliness toward physical activity: a comparison of the reliability of 3 questionnaires. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:473–83. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leslie E, Saelens B, Frank L, Owen N, Bauman A, Coffee N, et al. Residents’ perceptions of walkability attributes in objectively different neighbourhoods: a pilot study. Health Place. 2005;11:227–36. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Black J, Chen D. Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: An environment scale evaluation. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1552–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Atkinson JL, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Cain KL, Black JB. The association of neighborhood design and recreational environments with physical activity. Am J Health Promot. 2005;19:304–9. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.4.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Bourdeaudhuij I, Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Environmental correlates of physical activity in a sample of Belgian adults. Am J Health Promot. 2003;18:83–92. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marcus BH, Selby VC, Niaura RS, Rossi JS. Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise behavior change. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1992;63:60–6. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1992.10607557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marcus BH, Rossi JS, Selby VC, Niaura RS, Abrams DB. The stages and processes of exercise adoption and maintenance in a worksite sample. Health Psychol. 1992;11:386–95. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.6.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alcalay R, Alvarado M, Balcazar H, Newman E, Huerta E. Salud para su Corazon: a community-based Latino cardiovascular disease prevention and outreach model. Journal of Community Health. 1999;24:359–79. doi: 10.1023/a:1018734303968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marcus BH, Bock BC, Pinto BM, Forsyth LH, Roberts MB, Traficante RM. Efficacy of an individualized, motivationally-tailored physical activity intervention. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20:174–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02884958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Livingston G, Parker K, Fox S. In: Latinos Online, 2006–2008: Narrowing the gap. Center PH, editor. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center, Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fox S, Livingston G. Latinos online. Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lebo H, Corante P. UCLA News. Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles; 2003. Internet Use by Latinos Lower Than for Non-Latinos, but Online Use at Home Higher for Latinos, UCLA Study Reports. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gottman JM. The marriage clinic: a scientifically-based marital therapy. New York London: W. W. Norton; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gottman JM, Driver J, Tabares A. Building the sound marital house:An empirically derived couple therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baucom DH, Epstein N, LaTaillade JJ. Cognitive-behavioral therapy. 3. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]