Abstract

Research indicates that exercise is an efficacious intervention for depression among adults; however, little is known regarding its efficacy for preventing postpartum depression. The Healthy Mom study was a randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of an exercise intervention for the prevention of postpartum depression. Specifically, postpartum women with a history of depression or a maternal family history of depression (n=130) were randomly assigned to a telephone-based exercise intervention or a wellness/support contact control condition each lasting six months. The exercise intervention was designed to motivate postpartum women to exercise based on Social Cognitive Theory and the Transtheoretical Model. The primary dependent variable was depression based on the Structured Clinical Diagnostic Interview (SCID). Secondary dependent variables included scores on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, the PHQ-9, and the Perceived Stress Scale. The purpose of this paper is to describe the study design, methodology, and baseline data for this trial. Upon completion of the trial, the results will yield important information about the efficacy of exercise in preventing postpartum depression.

Keywords: Exercise, physical activity, postpartum depression, prevention, intervention, stress

1. Introduction

Research indicates that 10–15% of postpartum women receive a diagnosis of depression. [1]. Symptoms of depression include depressed mood, diminished interest, weight disturbance, sleep disturbance, agitation or psychomotor retardation, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, decreased concentration, and suicidal ideation [2]. Psychosocial treatments are effective for treating postpartum depression [3]; however, many of these women do not seek treatment [4]. The negative consequences of postpartum depression include difficulty caring for the newborn [5], poor infant-child bond [6], poor functional status of the mother [5], and relationship problems with the significant other [7]. Given these negative consequences and the issue that many women do not seek treatment, it is important to focus on effective strategies for preventing postpartum depression.

A Cochrane review indicated that women receiving psychosocial interventions for preventing postpartum depression were equally likely to develop postpartum depression than women receiving standard care [8]. Interventions examined have included interpersonal therapy [9], educational and counseling from nurses [10, 11], home visits from a nurse [12] and support groups and mailed materials [13]. Only a few studies have examined the efficacy of antidepressant medication for preventing postpartum depression and outcomes of these studies were mixed [14, 15]. One major disadvantage of antidepressant medications is that breastfeeding mothers may be reluctant to take them [16, 17].

Exercise is efficacious for treating depression in the general population [18]. The serotonin hypothesis suggests that exercise leads to increases in serotonin, which then leads to decreased depression [19]. Another example is the mastery hypotheses, which postulates that a sense of accomplishment after exercising leads to less depression [20]. Regardless of the mechanism, exercise may be an important intervention to explore for postpartum depression given the time, cost, and childcare constraints associated with traditional psychotherapies [21] and the lack of efficacy for these types of interventions [8]. Research suggests that exercise may be an efficacious treatment for postpartum depression; however, according to a recent review, the empirical evidence is mixed [18]. Specifically, only eight published randomized trials [22–30], to our knowledge, have examined the effect of exercise on postpartum depression. Many of these studies were limited by small sample sizes, short interventions, and a lack of a validated diagnostic interview for depression. Additionally, a majority of these studies examined only the treatment of symptoms rather than prevention.

The purpose of the Healthy Mom trial was to examine the effect of exercise on preventing postpartum depression. Our study improved upon the limitations of the previous studies by recruiting a larger sample size, implementing a longer intervention phase, and using a validated diagnostic instrument for depression in addition to focusing on the prevention of postpartum depression. The aims of this paper are to describe: (1) the study design and methodology; (2) baseline variables; (3) the relationship between the baseline variables in order to better understand how these variables may impact the outcome of the study, and (4) the success of various recruitment strategies.

2. Methods

The Healthy Mom study is a randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of a telephone-based exercise intervention for the prevention of postpartum depression among women identified to be at risk. Specifically, postpartum women who had a history of depression or a maternal family history of depression (n=130) were randomly assigned to either a telephone-based exercise intervention or to a wellness/support contact control condition each lasting six months. We chose a telephone-based intervention because several studies indicate that this type of intervention is efficacious [31, 32] and to reduce the time, cost, and childcare barriers associated with face-to-face interventions. The primary dependent variable was incidence of depression as measured by the Structured Clinical Diagnostic Interview (SCID). Secondary dependent variables included scores on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and the Perceived Stress Scale. Participants were recruited from targeted emails (emails sent by a local newspaper to women who had signed up to receive the newspaper online), print advertisements (e.g., local parent magazine, local newspaper), Craig’s List (e.g., website where local classified advertisements can be placed for free), and physician referrals. This study was approved by and in compliance with our university’s Institutional Review Board.

2.1 Participants

Participants were healthy, sedentary (exercising less than 60 minutes per week) women who were on average 5.7 weeks postpartum (all participants delivered live infants). The goal was to randomize participants as soon as possible after delivery depending upon when healthcare provider consent was provided. Specific exclusion criteria, assessed during the telephone screening interview included: (1) Pre-existing hypertension or diabetes; (2) currently enrolled in another exercise or weight management study; (3) less than 18 years of age; (4) another member of the household participating in the study; (5) unable to speak, comprehend, read, or write fluently in the English language; (6) unable to walk for 30 minutes continuously prior to pregnancy; (7) musculoskeletal problems such as arthritis, gout, osteoporosis, or back, hip or knee pain that may interfere with exercising; (8) exercise induced asthma; (9) any condition that would make exercise unsafe or unwise; (10) taking medication that interferes with heart rate response to exercise such as beta blockers; (11) hospitalization for a psychiatric disorder in the past six months; (12) current depressive episode based on the PHQ-9 (i.e., screening inventory for depression) and/or currently receiving antidepressant medication or psychotherapy for depression (those who were depressed and not in treatment were referred to their physician or psychiatrist for follow-up care). Participants agreed to be randomly assigned to either of the two study arms and read and signed a consent form approved by the University of Minnesota.

2.2 Procedure

2.2.1 Telephone Screening Interview

Participants were enrolled on a rolling basis over 17 months of the study. Potential participants contacted the research office by telephone or email and completed a telephone screening interview, which included the 10-item Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) [33, 34]. The Institutional Review Board approved our initial telephone screen prior to written consent. We obtained permission (verbally over the telephone) from the participant at the beginning of the telephone screening interview to ask and retain the information they provided on the telephone screening interview. Specifically, we made the following statement prior to asking any questions we would keep, “Do I have your permission to keep the information I ask you during this interview? The information will remain confidential and will be kept without your name attached.” In accordance with the IRB, we de-identified all data that were obtained among the ineligible participants. We needed to keep this data in order to compare eligible and ineligible participants on demographic and type of recruitment method (e.g., print advertisement) in addition to identifying the reasons for the ineligible participants.

In additional to the PAR-Q, participants were asked if they had a history of depression, which we defined as being told by a healthcare provider that they had depression or being prescribed antidepressant medication for depression. Participants were also asked about their family history of depression including mother, father, and siblings. Eligible and interested participants who were currently pregnant were instructed to call the study line after they had their baby. Research assistants also called potential participants a few weeks before their due date to remind them to call the study line once they had their baby.

2.2.2 Healthcare Provider Consent

During the telephone screening interview, the participant was asked if her healthcare provider could be contacted after she delivered her baby in order for the researchers to obtain healthcare provider consent to begin an exercise program. Therefore, the participant provided verbal consent to contact their healthcare provider as approved by the Institutional Review Board. A healthcare provider consent form was faxed immediately after completing the telephone screening interview for postpartum participants but for pregnant participants, the healthcare provider consent was faxed after they had the baby. The healthcare provider consent was a form that the healthcare provider completed that stated that it was safe for the participant to exercise. The provider returned the form via fax with a date when the participant could begin an exercise program. The healthcare provider provided consent to participate but were not directly involved in the study. Based on a previous pilot study [35], this method was established as the most efficient strategy to receive healthcare provider consent in a timely manner.

2.2.3 Informed Consent

Eligible and willing participants completed the informed consent process. Specifically, the study was explained and questions were answered over the telephone at the end of the telephone screening interview. Informed consent forms were mailed to eligible and willing participants upon completion of the telephone screening interview regardless of whether they were pregnant or postpartum. Participants completed the informed consent and returned the completed consent form in a self-addressed stamped envelope.

2.2.4 Study Protocol

Once the participant and healthcare provider consents were received and the participant had their baby, participants completed baseline questionnaires over the telephone. Participants also completed the PHQ-9 to assess depression and those already meeting criteria for depression were excluded from the study. Participants meeting criteria for depression were referred to their healthcare provider for follow-up. If participants expressed suicidal ideation during the intervention or assessment sessions, the counselor contacted the first author, who is a licensed psychologist, to assess the participant to determine if she had intent and/or a plan for suicide. The protocol stated that if the participant had intent or a plan, then appropriate steps would be taken including making a contract with the patient not to hurt herself and/or calling the authorities if applicable.

Eligible participants were then randomly assigned (1:1) to either the exercise intervention or the wellness/support contact control condition. The randomization assignment was generated in advance using permuted block randomization with randomly varying block sizes. Participants were informed by the counselor of their intervention assignment and the assessment coordinator was blind to the participant’s treatment condition. Upon completing the six-month intervention, participants completed the Structured Clinical Diagnostic Interview (SCID), 7-Day Physical Activity Recall Interview (PAR), and other assessment questionnaires (described below). Participants wore an ActiGraph accelerometer (ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, FL) to assess exercise ideally the week prior to the 6 month assessment.

2.3 Treatment conditions

Participants randomized to the exercise intervention received specific recommendations on the frequency and duration of exercise, along with behavioral and motivational strategies, to ensure adoption and maintenance of exercise. The wellness/support contact control group received the same number of telephone contacts from the counselor; however, the counselor only provided support for general issues related to health and wellness and did not provide information regarding exercise. The frequency of contacts is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Timeline and content of interventions.

| Month | Schedule | Content | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Exercise

|

Wellness

|

||

| 1 | Weekly | Overview/Prescription & Safety | Overview/Stress Prevention |

| Benefits of Exercise | Time Management | ||

| Goal Setting and Making Time | Sleep Management | ||

| Stage of Change | Safe Weight Loss | ||

| 2 | Biweekly | Social Support & Enjoyment | Nutrition – Superfoods |

| Self-Efficacy and IDEA method | Stress Management | ||

| 3 | Monthly | Making physical activity a habit | Nutrition Overview |

| 4 | Monthly | Relapse Prevention | Healthy Home Tips |

| 5 | Monthly | Exercise Maintenance Session | Maintenance Sessions |

| 6 | Monthly | Exercise Maintenance Session | Maintenance Sessions |

2.3.1 Exercise Intervention

The exercise intervention lasted six months and consisted of telephone counseling sessions, motivational print materials mailed to the participant, and completion of exercise logs. Participants were contacted weekly the first month, bi-weekly the second and third months, and monthly for the final 3 months. Each telephone session included a specific topic area; however, the counselor discussed any exercise related issues the participant presented (See Table 1).

The overall exercise prescription was standardized but the specific exercise program was individualized. The overall goal for all participants was to exercise 5 or more days per week for at least 30 minutes per session at an intensity of moderate or higher. The participants could choose what types of exercise they preferred to participate in and worked with the counselor to set goals regarding their exercise participation.

The sessions utilized motivational strategies based on Social Cognitive Theory [SCT; 36], and the Transtheoretical Model [37]. SCT postulates that exercise behavior is dependent upon behavior, cognitions, and the environment. The central focus of SCT as it applies to exercise is self-efficacy (i.e., one’s confidence that a task can be completed). Therefore, one focus of the intervention was to increase the participant’s self-efficacy to exercise despite having significant barriers (e.g., lack of time, energy). A second example related to social cognitive theory in that tips were given on how to make exercise more enjoyable.

Regarding the Transtheoretical model, the initial telephone sessions were targeted to stage of change. The stages include Precontemplation (i.e., not thinking about becoming active); Contemplation (i.e., thinking about becoming physically active); Preparation (i.e., taking steps to becoming physically active); Action (i.e., regularly physically active but for less than six months); and Maintenance (i.e., regularly physically active for more than six months). The objective was to meet the ACSM/CDC recommendation of exercising five or more days per week for 30 minutes or more each session [38] by one month. Therefore, the goal was for all participants to be to the action stage by one month. If they were not to the action stage by one month, the content of the session continued to be targeted to their particular stage of change level.

At the first session, the counselor calculated the target heart rate for moderate intensity exercise for each participant based on her age. Participants were taught how to monitor their heart rate to ensure maintenance of moderate intensity exercise. Participants were encouraged to first increase the frequency and later the duration of the exercise sessions. Safety was maintained utilizing a specific plan developed for each participant based upon recommendations by the American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists (ACOG) [39]. Participants also received training and handouts explaining how to recognize potential problems and were instructed to stop exercising immediately if problems occurred. They also received information about how to recognize and respond to angina and myocardial infarction symptoms.

All of the telephone sessions were specifically tailored to postpartum women and discussion topics included: (1) Maternal benefits of exercise; (2) types of exercise that can be done with the baby (e.g., walking/jogging with the baby in a stroller, using home exercise equipment); (3) tips for exercising despite fatigue (e.g., exercising in two 15-minute segments); (4) how to include exercise into a busy schedule (e.g., exercising at the beginning or end of the day when partners or other adult can watch the baby); (5) obtaining spousal/significant other support for exercise; (6) obtaining childcare for exercise; and (7) strategies for sticking with exercise despite frequent disruptions (e.g., breaking exercise up into 10 minute bouts). Participants also received an exercise DVD. The counselor instructed women who had a cesarean section to start more slowly and they were instructed to only do short walks for the first two weeks of the intervention period.

Exercise information was also mailed to participants that included tips for adopting and maintaining exercise, information on local resources for exercise (e.g., walking groups for new mothers, guide to walking trails, postpartum exercise classes in the community), and general information about exercise (e.g., how to select a good jogging stroller). Print-based motivational materials, specifically tailored to the postpartum period, were also mailed with information pertaining to topics discussed on the telephone. Handouts also included information on exercising while experiencing fatigue and sleep deprivation, tips for fitting exercise into the day, considerations when buying home exercise equipment, information about postpartum hydration (especially for those women who were breastfeeding), and suggestions for good postpartum exercise videos that could be used at home.

Participants logged their exercise daily by completing calendars documenting the type and duration of exercise. These logs were returned to the exercise counselor upon completion. In addition, participants set goals each week regarding the amount of exercise they would engage in during the week and discussed these goals as well as their logs with the counselor.

2.3.2. Wellness/Support Contact Control Arm

Participants randomly assigned to the wellness/support contact control arm received telephone calls from the counselor on the same schedule as the exercise intervention group. In order to control for non-specific factors (e.g., level of empathy, likeability), the same counselors delivered both the wellness/support contact control condition and the exercise intervention. The telephone calls were similar in duration to those received by the exercise intervention group. The counselor assessed and addressed general wellness topics including stress reduction, sleep, and nutrition. The counselor did not discuss issues related to exercise in the wellness/support condition. Participants in the wellness/support contact control condition also received print-based mailings on various topics related to wellness on the same schedule as the exercise intervention and completed the same assessments as the exercise condition

2.4 Participant Retention

Participant retention was defined as completing the SCID-I and the 7-Day Physical Activity Recall Interview at 6 months. Retention was encouraged by the following: (1) Participants were required to complete an assessment and a questionnaire packet prior to randomization to ensure they were committed to completing the study; (2) participants in the wellness/support arm received supportive telephone calls from the counselor equivalent in duration to the active intervention arm; (3) participants received a reminder call if questionnaires or assessments were not completed on time; (4) all participants were compensated $75 for completing the 6-month assessment; and (5) participants received a t-shirt at the end of the study. The scheduling of the assessment sessions was flexible in that participants were able to schedule their session in the morning, afternoon, or evening. Self-addressed stamped envelopes were provided to participants for all study related materials to be returned via mail so there was little time and no cost associated with returning study materials.

2.5. Quality Control

Quality control procedures were implemented to ensure that the study protocol was accurately executed. Specifically, the assessment coordinator (i.e., the individual conducting the assessments) was blinded to each participant’s study condition. Additionally, 10% of the telephone counseling and assessment sessions were audiotaped. These audiotapes have been and will continue to be reviewed by the first author, to ensure that the intervention and assessment sessions were administered based on the study protocols. The counselors were part of the study team, master’s level individuals, and were trained by the first author.

3. Measures

The study utilized both structured interviews and questionnaires to examine variables related to depression and exercise during the postpartum phase. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), 7-Day Physical Activity Recall Interview, the ActiGraph, and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale were administered at six months and the PHQ-9, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, and Perceived Stress Scale were administered at both baseline and six months. The specific measures are described in more detail below.

3.1 Primary dependent variable: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I)

The SCID-I is a semi-structured interview utilized to make major DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses [40]. The assessment coordinator assessed symptoms of depression including mood disturbance, loss of pleasure, weight disturbance, sleep disturbance, psychomotor disturbances, low energy level, low self-esteem, low cognitive functioning, suicidal thoughts, difficulty working, death of a loved one, and other physical illnesses. This interview is considered the gold standard in the assessment of depression and is widely used in depression intervention trials. The assessment coordinator was supervised by a licensed psychologist.

3.2 Exercise Measures

3.2.a. 7-Day Physical Activity Recall Interview

The 7-Day Physical Activity Recall (PAR) interview was utilized to assess physical activity level [41, 42]. The PAR interview has been used in a number of randomized controlled trials that examined exercise [43, 44] with several studies demonstrating both the reliability and the validity of the PAR (for a review, see [45]). Gross and colleagues [46] reported a test re-test reliability of 0.86 between two interviewers administering the interview on the same day. Validity was also established in a study that found a significant correlation between the PAR and the Caltrac, which is an objective measure of activity [47]. The PAR has also been shown to correlate with four-week exercise diaries [47] and is sensitive to changes in moderate-intensity exercise intervention trials [48].

3.2.b. ActiGraph

The ActiGraph motion monitor (ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL) was used as an objective measure of physical activity. The ActiGraph is a lightweight device that looks like a pedometer and uses an internal accelerometer to measure movement and intensity. Participants in both arms of the study wore the ActiGraph on their waist for seven days at 6 months. The ActiGraph is highly correlated with other validated monitors such as the CALTRAC [49] and TRITRAC [50] and has been shown to be effective in detecting both intermittent and continuous bouts of exercise behavior [50].

The study utilized a custom developed software program to reduce the ActiGraph data [51]. For days 2–7, data from 00:01 until midnight will be reduced and days 1 and 8 will be combined to form a composite seventh day of data. Blocks of time containing 60 minutes of continuous minutes of activity [52] (participant is likely not wearing the monitor) and days with less than 10 hours of data will be excluded. Average ActiGraph counts per minute will be calculated as the total counts for all included days summed and divided by the number of minutes the monitor was worn on the included days. The average number of minutes per day spent in moderate and vigorous exercise will be calculated using previously determined count cutoffs for adults [53].

Limitations of the ActiGraph include non-compliance with wearing the monitor, malfunction of the device resulting in lost data, and the inability to monitor certain types of exercise such as swimming. Thus, both the PAR (described above) and the ActiGraph were used to assess physical activity.

3.3 Secondary dependent measure

3.3.a PHQ-9

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item depression scale that assesses nine symptoms based on the DSM-IV depressive disorders. The scale includes items addressing diminished pleasure, depressed mood, sleep difficulty, low energy, appetite/eating changes, self-deprecation, difficulty concentrating, psychomotor changes, and suicidal thoughts; the Likert response scale ranges from 0–3 [54]. This scale has been found to have high sensitivity (73–88%) and specificity (88–98%), and has been recommended as an effective tool for diagnosing depression [55, 56], evaluating depression outcomes [57, 58], and identifying subthreshold depressive disorder [59].

3.3.b Edinburgh Postnatal Scale (EPS)

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale is a 10-item scale specifically designed to assess postpartum depression [60]. The EPDS includes a 4-point likert scale and items assess symptoms such as sadness, anxiety or worry, difficulty sleeping, and lack enjoyment of activities. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .86. This scale has been shown to have satisfactory specificity and sensitivity and is sensitive to change over time for depression [60].

3.3.c The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The PSQI is a 19-item self-report questionnaire that assesses sleep quality and disturbances during a one-month time period. The seven component subscales include subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. This scale has been shown to have adequate internal consistency (it was .59 in this study), test-retest reliability, validity, and diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 87%, respectively [61].

3.3.d Perceived Stress Scale

This scale has 14 items that measure the degree of perceived stress associated with specific situations [62]. The items in the questionnaire inquire how often the individual has felt or thought a certain way in the past month. One study found the two-day test retest reliability to be 0.85 [62]. Concurrent validity was also established by a significant correlation with the impact of life events scale (0.35 and 0.24) [62].

3.4. Demographic, Lifestyle, and Other Variables

Demographic questions were administered at baseline including questions that assessed age, ethnicity, race, occupation, marital status, number of children living at home, number of previous depressive episodes, family history of depression, education, smoking status, socioeconomic status, previous pregnancies and births, height, weight, and medication use. The 6-month survey re-assessed weight, medication use, and breastfeeding practice.

4. Statistical Analysis

The sample size was determined a priori assuming a two-sided type I error of 0.05, a power of at least 80% and a 6 month postpartum depression rate of 13% and 40% for exercise intervention and wellness/support contact control arms, respectively. Power calculations indicated that 51 participants in each of the two arms resulted in 85% power to detect statistically significant main effects using the Fisher exact test. We calculated the descriptive statistics for the baseline demographics and psychosocial variables for the study sample. Categorical variables were summarized by percentages, and continuous variables were summarized by means and standard deviations. Chi-square tests or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables were used to compare the baseline variables by study arm. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the correlations among psychosocial variables.

5. Results

5.1 Recruitment Strategies

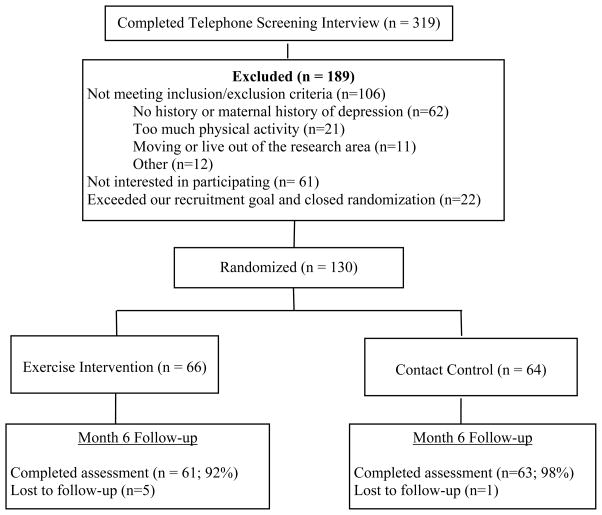

The participant flow throughout the study is summarized in Figure 1. We successfully recruited 130 participants, which exceeded our original recruitment goal of 120. We also retained 95% of our sample at six months. Table 2 summarizes the number of participants recruited from each recruitment strategy. Most participants called our study telephone line during pregnancy rather than during the postpartum phase. The majority of potential participants screened (n=319) were recruited using the targeted email (55%), followed by a local parent magazine (15%), and Craig’s List (9%). To better understand which recruitment methods were successful for targeting women from minority backgrounds or populations, we analyzed the recruitment data separately for minority and Caucasian individuals. We found that among the minority participants screened (n=53), 32% were from a local parent magazine, 30% from targeted emails, and 9% from Craig’s list. Among Caucasian individuals completing the telephone screening interview, 60% were from the targeted email, 12% from the local parent magazine, 9% from Craig’s list, and 9% from other sources.

Figure 1.

Healthy Mom Trial Flowchart

Table 2.

Number of participants by recruitment method.

| Recruitment Method | All Participants Screened (n=319) | Randomized (n=130) | Not Randomized* (n=189) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Email | 176 (55%) | 62 (48%) | 114 (60%) |

| Local Parent Magazine | 48 (15%) | 20 (15%) | 28 (15%) |

| Craig’s List | 28 (9%) | 18 (14%) | 10 (5%) |

| Clinic (flyer or referral) | 9 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 6 (3%) |

| Friend | 17 (5%) | 9 (7%) | 8 (4%) |

| Newspaper Ad | 10 (3%) | 9 (7%) | 1 (1%) |

| Other | 31 (10%) | 9 (7%) | 22 (12%) |

Ineligible or not interested after obtaining more information during screening interviewing

5.2 Demographics of the Randomized Sample

The baseline demographics by study arm are presented in Table 3. The study sample was predominately Caucasian (82.3%) and married (82.2%). The average age was 31.5 and this was not the first child for most women (75.8%). Most participants had at least some college education (95.4%). There were no significant differences between the treatment arms on any of the demographic variables (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics by group.

| Variable | Total sample (n=130) | Exercise (n= 66) | Wellness (n=64) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (average in years) | 31.54(4.95) | 31.69(5.27) | 31.39(4.63) | .73 |

| Race (%) | .69 | |||

| Caucasian | 82.3% | 80.3% | 84.4% | |

| African-American | 6.9% | 9.1% | 4.7% | |

| Other | 10.8% | 10.6% | 10.9% | |

| Marital Status (% Married) | 82.2% | 83.3% | 81.0% | .72 |

| Education (%) | .74 | |||

| Less than high school graduate | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| High school graduate | 4.7% | 3.0% | 6.4% | |

| Some college | 26.4% | 27.3% | 25.4% | |

| College graduate | 41.1% | 43.9% | 38.1% | |

| Post-graduate work | 27.9% | 25.8% | 30.2% | |

| Income (%) | .17 | |||

| Under $10,000 | 7.9% | 4.7% | 11.1% | |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 5.5% | 7.8% | 3.2% | |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 4.7% | 1.6% | 7.9% | |

| $30,000–$39,999 | 11.0% | 12.5% | 9.5% | |

| $40,000–$50,000 | 7.9% | 10.9% | 4.8% | |

| Over $50,000 | 59.1% | 56.3% | 61.9% | |

| Don’t know/refuse | 3.9% | 6.3% | 1.6% | |

| First Biological Child (%) | 24.2% | 21.2% | 27.4% | .41 |

| Newborn Age (weeks) | 5.7% | 6.8% | 5.2% | .20 |

| Other children (%) | .06 | |||

| None | 16.3% | 9.1% | 23.8% | |

| One | 38.0% | 47.0% | 28.6% | |

| Two | 24.8% | 22.7% | 27.0% | |

| Three or more | 20.9% | 21.2% | 20.6% |

5.3 Baseline Psychosocial Variables

The means and standard deviations for the baseline psychosocial variables are summarized in Table 4. There were no significant differences between the PHQ-9 (depression scale), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) between participants in the two study arms. Regarding the sleep index, participants went to bed on average at 10:30 p.m. (ranging from 7:30 p.m. to 2:30 a.m.) and slept an average of 6.2 hours per night (ranging from 3 to 10 hours). The three baseline measures were all correlated with one another. Specifically, the PHQ-9 (depression scale) scores were significantly correlated with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) scores, r = .43, p < .0001 and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores, r = .41, p < .0001. Also, the PSS and PSQI scores were significantly correlated with one another, r = .22, p < .05. Higher levels of stress were related to a higher level of sleep disturbance.

Table 4.

Baseline psychosocial variable scores by group.

| Variable | Total sample (n=130) | Exercise (n= 66) | Wellness (n=64) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | 5.98(3.83) | 5.42(3.28) | 6.56(4.27) | .09 |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | 28.49(3.65) | 28.44(3.72) | 28.55(3.62) | .87 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) | 7.11(2.84) | 7.11(2.61) | 7.11(3.08) | .995 |

5. Discussion

Traditional interventions such as psychotherapy pose several barriers for new mothers including childcare, cost, and time. Additionally, antidepressant medications may not be ideal due to their side effects and the frequent reluctance of breastfeeding mothers to take these medications [16, 17]. Therefore, there is a need to explore new and innovative interventions for preventing postpartum depression.

The primary aim of the Healthy Mom study was to examine the efficacy of a telephone-based exercise intervention for the prevention of postpartum depression. Diagnosed depression utilizing the SCID-I was our primary dependent variable. However, because many women experience depressive symptoms without meeting the full diagnosis of depression, it is important to also assess symptoms of depression. Therefore, the PHQ-9 and Edinburgh Postnatal Scale, two continuous measures of depression were included to assess depressive symptoms. Another consideration in any randomized controlled trial is whether or not to include a contact control or usual care condition. We chose to use a wellness/support contact control condition because we felt it was important to determine if exercise was important in addition to the basic social support provided by the regular contact of a counselor.

Equity between the two randomized groups appears to have been attained in that there were no baseline differences on the demographic or psychosocial variables. As expected, the participants in the study were sleep deprived (average of 6.2 hours of sleep per night). Because one of the exclusion criteria was current depressive episode, it is not surprising that the PHQ-9 scores were relatively low. However, participants reported relatively high perceived stress when compared to previous studies among the general population. Specifically, the average score was 28 in our sample compared to a score 16 that has been found in a previous study including a general population of women [63].

Recruitment is frequently the most challenging component of randomized controlled trials. Therefore, it is important to examine which recruitment strategies are successful for recruiting study samples. In our overall sample, the targeted email was the most successful recruitment strategy. Interestingly, recruiting through more traditional methods such as referrals from physicians and advertisements in a local newspaper were unsuccessful. We contacted numerous physician offices in our local area to inform physicians of our study and offered to give presentations to the physician groups to discuss postpartum depression in general and our study in particular. A few physician offices allowed us to send flyers to their offices but none were interested in the presentation. Regarding the advertisement, we placed one Sunday advertisement in the local newspaper, which resulted in very few telephone calls. In comparison to previous physical activity studies where most participants were recruited through print advertisements [43], it appears that successful recruitment strategies have significantly changed with advances in technology and communication. Additional research is needed to better understand new and evolving successful recruitment strategies for randomized controlled trials.

In addition to analyzing overall recruitment, it is also important to examine which recruitment strategies will attract a broad diversity of participants. Therefore, we analyzed which recruitment strategies were most successful for different racial groups. Specifically, almost two-thirds of the Caucasian individuals were recruited through a targeted email sent out by a local newspaper whereas only one-third of the minority participants were recruited via this email. Individuals receiving this email were women between the ages of 18–40 who had signed up to receive the local newspaper online. Additionally, one-third of the minority participants were recruited through a local parent magazine whereas only 12% of the Caucasian individuals were recruited through this magazine. This magazine is distributed throughout the state through physician offices, local childcare agencies, and child-related retail stores. Additional research is needed to better understand which recruitment methods work best for different racial groups.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample size was relatively small (n=130). However, because this is one of the first studies to examine the efficacy of an exercise intervention for the prevention of postpartum depression, we felt it was most appropriate to do a small-scale study prior to a larger study. Second, there was no follow-up after the six month intervention and therefore, it is unclear to what degree women may have continued to exercise after the six month intervention period. Third, the internal consistency for the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was relatively low (.59) although this is not surprising given the sporadic sleep patterns of postpartum women (i.e., may have high napping but low nighttime sleep). Finally, our sample lacked diversity regarding socioeconomic status, education, and race/ethnicity. We did identify recruitment strategies that worked better for minority individuals and these should be explored further in future studies.

6. Conclusion

The Healthy Mom study is one of the first trials to examine the efficacy of an exercise intervention for the prevention of postpartum depression. Given the time, cost, and childcare constraints of traditional interventions for postpartum depression, evaluations of new and innovative interventions are needed. We demonstrated the feasibility of recruiting and retaining postpartum women in an exercise intervention study. We also learned that successful recruitment strategies have changed in recent years as the use of communication technology has evolved. Additional studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further explore the efficacy of exercise interventions for postpartum depression.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported through a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (#MH73820). Dr. Guo was supported in part by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources (grant number 1UL1RR033183) and a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (grant number 8 ULI TR000114-02). We would like to acknowledge the many contributions of Katie Schuver, Laura Polikowsky, and Silke Moeller for contributing to the conduct of this study. We would also like to acknowledge the participants in this study without whom none if this would have been possible.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dietz PM, Williams SB, Callaghan WM, Bachman DJ, Whitlock EP, Hornbrook MC. Clinically identified maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancies ending in live births. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1515–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennis CL, Hodnett E. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006116. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006116.pub2. (Updated in 2009 with no changes to the conclusion) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Logsdon MC, Wisner KL, Pinto-Foltz MD. The impact of postpartum depression on mothering. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(5):652–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hipwell AE, Goossens FA, Melhuish EC, Kumar R. Severe maternal psychopathology and infant-mother attachment. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12(2):157–175. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400002030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman JH. Paternal postpartum depression, its relationship to maternal postpartum depression, and implications for family health. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(1):26–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis CL, Creedy D. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4):CD001134. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001134.pub2. (Updated in 2008 with no changes to the conclusion) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zlotnick C, Johnson SL, Miller IW, Pearlstein T, Howard M. Postpartum depression in women receiving public assistance: pilot study of an interpersonal-therapy-oriented group intervention. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(4):638–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tam WH, Lee DT, Chiu HF, Ma KC, Lee A, Chung TK. A randomised controlled trial of educational counselling on the management of women who have suffered suboptimal outcomes in pregnancy. BJOG. 2003;110(9):853–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waldenstrom U, Brown S, McLachlan H, Forster D, Brennecke S. Does team midwife care increase satisfaction with antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care? A randomized controlled trial. Birth. 2000;27(3):156–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong KL, Fraser JA, Dadds MR, Morris J. A randomized, controlled trial of nurse home visiting to vulnerable families with newborns. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999;35(3):237–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid M, Glazener C, Murray GD, Taylor GS. A two-centred pragmatic randomised controlled trial of two interventions of postnatal support. BJOG. 2002;109(10):1164–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wisner KL, Perel JM, Peindl KS, Hanusa BH, Piontek CM, Findling RL. Prevention of postpartum depression: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(7):1290–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wisner KL, Perel JM, Peindl KS, Hanusa BH, Findling RL, Rapport D. Prevention of recurrent postpartum depression: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(2):82–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buist A, Bilszta J, Barnett B, Milgrom J, Ericksen J, Condon J, et al. Recognition and management of perinatal depression in general practice--a survey of GPs and postnatal women. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(9):787–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitton A, Warner R, Appleby L. The pathway to care in postnatal depression: Women’s attitudes to postnatal depression and its treatment. Br J Gen Prac. 1996;46:427–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mead GE, Morley W, Campbell P, Greig CA, McMurdo M, Lawlor DA. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD004366. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaouloff F. The serotonin hypothesis. In: Morgan WP, editor. Physical activity and mental health. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; 1997. pp. 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biddle SJH, Mutrie N. Depression and other mental illnesses. In: Biddle SJH, Mutrie N, editors. Psychology of physical activity: Determinants, well being, and interventions. London: Routledge; 2001. pp. 202–235. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis BA, Kennedy BF. The effect of exercise on depression during pregnancy and postpartum: A review. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011;5:370–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hart SL, Hart TA. The Future of Cognitive Behavioral Interventions within Behavioral Medicine. J Cogn Psychother. 2010;24:344–53. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong KJ, Edwards H. The effects of exercise and social support on mothers reporting depressive symptoms: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2003;12:130–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0979.2003.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong K, Edwards H. The effectiveness of a pram-walking exercise programme in reducing depressive symptomatology for postnatal women. Int J Nurs Pract. 2004;10(4):177–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2004.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daley A, Winter H, Grimmett C, McGuinness M, McManus R, MacArthur C. Feasibility of an exercise intervention for women with postnatal depression: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Prac. 2008;58:178–83. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X277195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Da Costa D, Lowensteyn I, Abrahamowicz M, Ionescu-Ittu R, Dritsa M, Rippen N, et al. A randomized clinical trial of exercise to alleviate postpartum depressed mood. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;30:191–200. doi: 10.1080/01674820903212136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dritsa M, Da Costa D, Dupuis G, Lowensteyn I, Khalife S. Effects of a homebased exercise intervention on fatigue in postpartum depressed women: results of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:179–87. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heh SS, Huang LH, Ho SM, Fu YY, Wang LL. Effectiveness of an exercise support program in reducing the severity of postnatal depression in Taiwanese Women. Birth. 2008;35:60–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koltyn KF, Schultes SS. Psychological effects of an aerobic exercise session and a rest session following pregnancy. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1997;37:287–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norman E, Sherburn M, Osborne RH, Galea MP. An exercise and education program improves well-being of new mothers: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2010;90:348–55. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King AC, Friedman R, Marcus B, Castro C, Napolitano M, Ahn D, et al. Ongoing physical activity advice by humans versus computers: the Community Health Advice by Telephone (CHAT) trial. Health Psychol. 2007;26(6):718–27. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcus BH, Napolitano MA, King AC, Lewis BA, Whiteley JA, Albrecht A, et al. Telephone versus print delivery of an individualized motivationally tailored physical activity intervention: Project STRIDE. Health Psychol. 2007;26:401–9. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardinal BJ, Esters J, Cardinal MK. Evaluation of the revised physical activity readiness questionnaire in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28(4):468–72. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199604000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas S, Reading J, Shephard RJ. Revision of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) Can J Sport Sci. 1992;17(4):338–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis BA, Martinson BC, Sherwood NE, Avery MD. A Pilot Study Evaluating a Telephone-Based Exercise Intervention for Pregnant and PostPartum Women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56:127–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2010.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1423–34. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616b27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Artal R, O’Toole M. Guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37(1):6–12. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.1.6. discussion 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbons M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV—clinical version (SCID-CV) (User’s Guide and Interview) Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blair SN, Haskell WL, Ho P, Paffenbarger RS, Vranizan KM, Farquhar JW, et al. Assessment of habitual physical activity by a seven-day recall in a community survey and controlled experiments. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122(5):794–04. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD, Fortmann SP, Rogers T, Blair SN, Paffenbarger RS. Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121(1):91–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunn AL, Marcus BH, Kampert JB, Garcia ME, Kohl HW, Blair SN. Reduction in cardiovascular disease risk factors: 6-month results from Project Active. Prev Med. 1997;26(6):883–92. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcus BH, Lewis BA, Williams DM, Dunsiger S, Jakicic JM, Whiteley JA, et al. A comparison of Internet and print-based physical activity interventions. Arc Intern Med. 2007;167(9):944–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pereira MA, FitzerGerald SJ, Gregg EW, Joswiak ML, Ryan WJ, Suminski RR, et al. A collection of Physical Activity Questionnaires for health-related research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(6 Suppl):S1–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gross LD, Sallis JF, Buono MJ, Roby JJ, Nelson JA. Reliability of interviewers using the Seven-Day Physical Activity Recall. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1990;61(4):321–5. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1990.10607494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobs DR, Ainsworth BE, Hartman TJ, Leon AS. A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activity questionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(1):81–91. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunn AL, Marcus BH, Kampert JB, Garcia ME, Kohl HW, III, Blair SN. Comparison of Lifestyle and Structured Interventions to Increase Physical Activity and Cardiorespiratory Fitness. JAMA. 1999;281(4):327–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melanson EL, Freedson PS. Validity of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. (CSA) activity monitor. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(6):934–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masse LC, Fulton JE, Watson KL, Heesch KC, Kohl HW, Blair SN, Tortolero SR. Detecting bouts of physical activity in a field setting. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70(3):212–9. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1999.10608041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sirard JR, Riner WF, McIver KL, Pate RR. Physical Activity and Active Commuting to Elementary School. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(12):2062–69. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000179102.17183.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–8. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard JR. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(5):777–81. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509–21. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, Delucchi KL, Spitzer RL. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):547–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dobscha SK, Corson K, Hickam DH, Perrin NA, Kraemer DF, Gerrity MS. Depression decision support in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(7):477–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-7-200610030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gensichen J, Torge M, Peitz M, Wendt-Hermainski H, Beyer M, Rosemann T, et al. Case management for the treatment of patients with major depression in general practices--rationale, design and conduct of a cluster randomized controlled trial--PRoMPT (PRimary care Monitoring for depressive Patient’s Trial) [ISRCTN66386086]--study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lowe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Grafe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) J Affect Disord. 2004;81(1):61–6. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. J Psychiatr Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D. Who’s stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006 and 2009. J Appl Soc Psychol. In press. [Google Scholar]