Summary

Although acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) has long been recognized for its morphological and cytogenetic heterogeneity, recent high-resolution genomic profiling has demonstrated a complexity even greater than previously imagined. This complexity can be seen in the number and diversity of genetic alterations, epigenetic modifications, and characteristics of the leukaemic stem cells. The broad range of abnormalities across different AML subtypes suggests that improvements in clinical outcome will require the development of targeted therapies for each subtype of disease and the design of novel clinical trials to test these strategies. It is highly unlikely that further gains in long-term survival rates will be possible by mere intensification of conventional chemotherapy. In this review, we summarize recent studies that provide new insight into the genetics and biology of AML, discuss risk stratification and therapy for this disease, and profile some of the therapeutic agents currently under investigation.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukaemia, AML, childhood leukaemia

Introduction

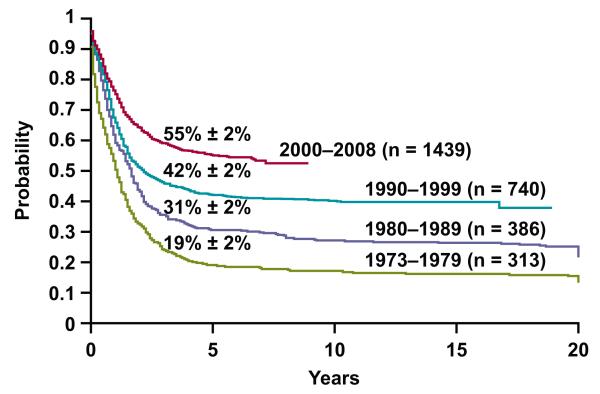

Tremendous progress has been made in the treatment of childhood acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) over the past 40 years: data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results 9 study show that survival rates of children younger than 20 years increased from less than 20% in the 1970s to 31% in the 1980s, 42% in the 1990s, and 55% for patients who were diagnosed from 2000-2008 (www.seer.cancer.gov/popdata; Fig. 1). These improvements are attributable to intensification of chemotherapy, selective use of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), improvements in supportive care, refinements in risk classification, and the use of minimal residual disease (MRD) to monitor response to therapy. However, the cure rates for many subtypes of childhood AML remain unacceptably low, and novel therapies are needed. Recent advances in the characterization of the leukaemic stem cell and in the understanding of the biology and genetics of AML may lead to such therapies in the near future.

Figure 1. Overall survival of patients who were less than 20 years of age and diagnosed with AML during the time periods indicated.

The data were obtained from www.seer.cancer.gov/popdata.

Biology and Genetics of AML

The cancer stem cell model proposes that AML cells, like normal haematopoietic progenitors, are hierarchically organized into compartments that contain leukaemic stem cells (LSCs) that have unlimited self-renewal capacity and are capable of propagating leukaemia when transplanted into immunocompromised mice, as well as compartments that lack such cells (Magee et al, 2012; Nguyen et al, 2012). Recent studies demonstrate considerable heterogeneity in LSCs both between and within individual patients (Eppert et al, 2011; Goardon et al, 2011; Gerber et al, 2012). These studies also demonstrate the clinical significance of LSCs and suggest that targeting of the LSC population is critical for the development of effective therapies. It is therefore important that the preclinical evaluation of new drugs includes xenograft assays that allow testing of these agents in functionally-defined LSC compartments. Promising agents that may selectively target LSCs while sparing normal HSCs include parthenolide analogs (Guzman et al, 2007a), compound TDZD-8 (Guzman et al, 2007b), and monoclonal anti-CD47 antibodies (Majeti et al, 2009; Majeti, 2011).

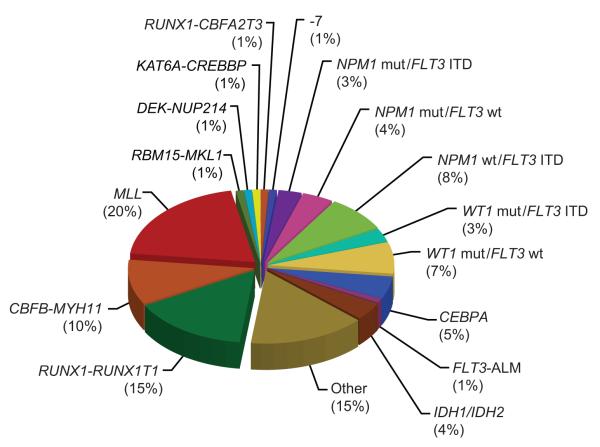

All subtypes of AML probably share abnormalities in common pathways that regulate proliferation, differentiation, and cell death. These include mutations that impart proliferative and survival signals, and mutations that lead to differentiation arrest or enhanced self-renewal (Pui et al, 2011). The first category includes lesions that constitutively activate protein kinases, such as FLT3, cKIT, and RAS, whereas the second comprises gene fusions that are commonly generated by chromosomal translocations, such as t(8;21)(q22;q22)/RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and inv(16)(p13.1;q22)/CBFB-MYH11 (Fig. 2). The prognostic and therapeutic implications of selected mutations are discussed below.

Figure 2. Approximate frequencies of recurrent genetic lesions in childhood AML.

Frequencies are estimated from (Pui et al, 2011; Meshinchi et al, 2006a; Staffas et al, 2011; Harrison et al, 2010; Ho et al, 2009; Brown et al, 2007; Hollink et al, 2009a; Balgobind et al, 2009; Hollink et al, 2009b; Andersson et al, 2011).

ALM, activation loop mutation; ITD, internal tandem duplication; mut, mutation; wt, wild-type

Genome-wide analyses have been used to determine the full complement of genetic lesions required for leukaemogenesis. Genomic profiling of DNA copy number alterations and loss of heterozygosity (Radtke et al, 2009; Kuhn et al, 2012), as well as the complete sequencing of AML genomes (Ley et al, 2008; Mardis et al, 2009), indicate that AML contains fewer genetic alterations than do other malignancies. Paediatric AML in particular contains few genomic alterations, with only 2.4 somatic copy-number alterations per leukaemia and no copy-number alterations in about one-third of cases, suggesting that the development of AML may require fewer genetic alterations than other malignancies (Radtke et al, 2009). Nevertheless, novel lesions have been identified, such as mutations in the IDH1 and DNMT3A genes (Mardis et al, 2009; Andersson et al, 2011; Ley et al, 2010). Interestingly, the frequency of mutations in many genes, including IDH1, IDH2, DNMT3A, NPM1, and FLT3 are more common in adult AML than in childhood cases.

Recently, investigators from Washington University used whole-genome sequencing of paired samples to identify mutations associated with the progression of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) to AML (Walter et al, 2012) and those associated with the development of relapse (Ding et al, 2012). The authors demonstrate that nearly all bone marrow cells in patients with MDS and AML are clonal in origin and that all clones contain at least one mutation in a coding gene (Walter et al, 2012). In all seven cases analysed, the progression from MDS to AML was characterized by the persistence of an MDS-associated clone as well as the emergence of subclones harbouring new mutations. Similar evidence of clonal evolution was demonstrated by the sequencing of samples obtained from eight patients with AML at the time of initial diagnosis and at relapse (Ding et al, 2012). In each case, the founding clone or a subclone of the founding clone was detected in all relapsed samples, indicating that therapy had failed to eradicate those clones and suggesting that the new mutations in the relapsed samples may contribute to resistance to additional therapy.

Prognostic factors

Genetic features and response to therapy are important determinants of clinical outcome and are used for risk stratification in most contemporary clinical trials. Table I summarizes the genetic abnormalities that have proven clinical implications, those likely to have clinical relevance, and others with unknown but potential relevance.

Table I.

Genetic abnormalities in paediatric acute myeloid leukaemia

| Karyotype | Affected Genes | %a | Clinical significance |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| t(8;21)(q22;q22) | RUNX1-RUNX1T1 | 15 | Favourable prognosis |

| Not candidates for HSCT | |||

|

| |||

| inv(16)(p13.1;q22) | CBFB-MYH11 | 10 | Favourable prognosis |

| t(16;16)(p13.1;q22) | Not candidates for HSCT | ||

|

| |||

| −7 | Unknown | 1 | Poor prognosis |

|

| |||

| 11q23 | MLL rearrangements | 20 | |

| MLL-MLLT11 | Favourable prognosis | ||

| t(1;11)(q21;q23) | MLL-MLLT3 | 1 | Intermediate prognosis |

| t(9;11)(p12;q23) | MLL-MLLT4 | 8 | Poor prognosis |

| t(6;11)(q27;q23) | MLL-MLLT10 | 1 | Poor prognosis |

| t(10;11)(p12;q23) | 1 | Intermediate prognosis | |

| Others | 9 | ||

|

| |||

| t(1;22)(p13;q13) | RBM15-MKL1 | 1 | Megakaryoblastic leukaemia |

| Unknown prognosis | |||

|

| |||

| t(6;9)(p23;q34) | DEK-NUP214 | 1 | Poor prognosisb |

|

| |||

| t(8;16)(p11;p13) | KAT6A-CREBBP | 1 | Poor prognosisb |

|

| |||

| t(16;21)(q24;q22) | RUNX1-CBFA2T3 | 1 | Poor prognosisb |

|

| |||

| Normalc | FLT3-ITD | 12 | Poor prognosis if high ratio of mutant to wild-type allele |

| May benefit from HSCT or treatment with FLT3 inhibitors |

|||

|

| |||

| Normalc | NPM1 | 8 | Favourable prognosis except in cases with FLT3-ITD |

|

| |||

| Normalc | CEBPA | 5 | Favourable prognosis probably limited to cases with biallelic mutations |

|

| |||

| Normalc | WT1 | ||

| Mutation | 10 | Unknown | |

| SNP rs16754 | 25 | May be associated with favourable outcome |

|

|

| |||

| Normalc | IDH1 and IDH2 | ||

| Mutation | 4 | Unknown | |

| IDH1 SNP rs11554137 | 10 | Unknown | |

|

| |||

| Normalc | RUNX1 | Rare | Unknown |

|

| |||

| Normalc | TET2 | Rare | Unknown |

|

| |||

| Normalc | DNMT3A | Rare | Unknown |

|

| |||

| t(15;17)(q22;q12) | PML-RARA | NA | Observed only in APL |

| Favourable outcome | |||

Abbreviations: HSCT, haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation; ITD, internal tandem duplication; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; NA, not available; APL acute promyelocytic leukaemia.

% of non-APL cases with each abnormality. Note that some alterations co-exist, such as NPM1 mutation and FLT3-ITD, as shown in Figure 2.

The poor prognosis of these rare translocations has been firmly established only in adult AML.

These mutations often occur in cases with normal karyotypes, but are also seen in cases with other abnormalities.

The low-risk classification of patients whose leukaemic blasts contain the t(8;21)(q22;q22)/RUNX1-RUNX1T1, inv(16)(p13.1;q22)/CBFB-MYH11, or t(16;16)(p13.1;q22)/CBFB-MYH11 (collectively referred as core-binding leukaemia) was proposed by investigators from the Medical Research Council (MRC) in 1998 (Grimwade et al, 1998) and is still used today (Rubnitz et al, 2010a; Vardiman et al, 2009). The favourable impact of these lesions in children with AML was recently confirmed by the MRC (Harrison et al, 2010), the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (BFM) study group (von Neuhoff et al, 2010), and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (Rubnitz et al, 2010a), all of whom reported overall survival (OS) rates of greater than 90% for children with t(8;21) or inv(16). Although KIT mutations confer an inferior prognosis in adults with core-binding leukaemia, their prognostic significance in children with this subtype of AML remains unproven (Pollard et al, 2010). Hence, most treatment protocols classify all children with core-binding leukaemia as having low-risk disease, regardless of KIT mutations or other genetic abnormalities.

In adults and children with AML, mutations of the NPM1 gene are observed primarily in cases with normal karyotypes, and often in association with internal tandem duplications of the FLT3 gene (FLT3-ITD) (Marcucci et al, 2011; Brown et al, 2007; Hollink et al, 2009a; Staffas et al, 2011). In adults with normal karyotypes and wild-type FLT3, NPM1 mutations are associated with a favourable prognosis (Marcucci et al, 2011). Although NPM1 mutations are less common in childhood AML (Fig. 2), they appear to be associated with a similarly favourable outcome when they occur in the presence of wild-type FLT3. Children whose blasts contain NPM1 mutations, normal karyotypes, and wild-type FLT3 have an outcome similar to that of children with core-binding leukaemia, with OS rates greater than 80%.

Like NPM1, biallelic mutations of CEBPA are associated with normal karyotypes and a favourable outcome in adults with AML (Marcucci et al, 2011). Recently, investigators from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) reported that CEBPA mutations were detected in 4.5% of patients, including 17% of those with normal karyotypes, and independently predicted a favourable outcome (Ho et al, 2009). By contrast, a study of 185 patients treated in Nordic Society for Paediatric Haematology and Oncology (NOPHO) trials found that CEBPA status did not add significant prognostic information (Staffas et al, 2011). These conflicting reports may reflect the relatively small numbers of patients with CEBPA mutations in each study and the observation that in adults with AML, double mutations of CEBPA are biologically distinct from those with single mutations; only biallelic mutations are associated with a favourable outcome. Nevertheless, recently developed clinical trials for childhood AML classify patients who have normal karyotypes, wild-type FLT3, and mutations of NPM1 or biallelic mutations of CEBPA as having low-risk disease.

Genetic abnormalities for which there is strong evidence of an association with a high risk of relapse in childhood AML include monosomy 7 (Hasle et al, 2007), and FLT3-ITDs (Meshinchi et al, 2006a; Staffas et al, 2011; Levis & Small, 2003). Point mutations and ITDs of the FLT3 gene occur in about 15% of paediatric AML cases (Meshinchi et al, 2006a; Staffas et al, 2011) and may be gained or lost at the time of relapse (Bachas et al, 2010). Meshinchi et al, (2006a) confirmed the poor outcome of patients with FLT3-ITDs and demonstrated that survival was particularly poor in patients with high ratios of FLT3-ITD to wild-type FLT3. In that study, a FLT3-ITD/wild-type allelic ratio greater than 0.4 was an independent predictor of a poor outcome and was associated with a progression-free survival rate of 16%. Recent studies have confirmed the independent prognostic significance of FLT3-ITDs (Staffas et al, 2011) and have suggested that the outcome of these patients can be improved by HSCT (Meshinchi et al, 2006b; Dezern et al, 2011). It should be noted, however, that although FLT3-ITDs sometimes occur in cases with normal karyotypes, cryptic mutations have been detected by molecular techniques. In one such study, Hollink et al (2011) identified the NUP98/NSD1 fusion in 16% of karyotypically-normal childhood AML cases, 91% of which harboured a FLT3-ITD. In these cases, it is unknown whether the leukaemogenesis and the dismal prognosis are driven by the FLT3 mutation, the NUP98/NSD1 fusion, or interactions between them. Nevertheless, because the poor outcome of patients with FLT3-ITD has been documented in several large studies, many investigators consider these patients to have high-risk disease.

Uncommon genetic abnormalities that probably confer a poor prognosis include t(6;9)(p23;q34)/DEK-NUP214, t(8;16)(p11;p13)/KAT6A-CREBBP and t(16;21)(q24;q22)/RUNX1-CBFA2T3 (Slovak et al, 2006; Haferlach et al, 2009; Park et al, 2010), but because of the rarity of these lesions in childhood AML, their independent prognostic significance remains unknown.

AML with rearrangements of the MLL gene may be the most heterogeneous of all genetic subtypes of this disease (Balgobind et al, 2009; Balgobind et al, 2011). Although one study (Rubnitz et al, 2002) suggested that t(9;11)(p12;q23) confers a favourable outcome, this finding has not been confirmed in other trials (Harrison et al, 2010; Balgobind et al, 2009). For example, the outcome of patients with t(9;11) was not different from that of patients with other 11q23 translocations treated on the MRC AML10 and AML12 trials (Harrison et al, 2010). Moreover, among patients treated on the AML-BFM 98 trial (von Neuhoff et al, 2010), the outcome of patients with t(9;11) and additional aberrations, as well as that of patients with MLL rearrangements other than t(9;11) and t(11;19), was unfavourable. The results of an international study (Balgobind et al, 2009) of 756 children with 11q23/MLL rearrangements demonstrated that prognosis depended largely on the translocation partner. In that study, the t(6;11)(q27;q23), t(10;11)(p12;q23) and t(10;11)(p11.2;q23) were associated with poor outcomes, whereas the t(1;11)(q21;q23) was associated with an excellent outcome, further highlighting the heterogeneity within this group.

The prognostic implications of abnormalities of the Wilms tumour 1 (WT1) gene are not clear in either adults or children with AML (Marcucci et al, 2011; Hollink et al, 2009b; Ho et al, 2010; Ho et al, 2011a). Although the results of one study suggested that WT1 mutations, which occur in about 10% of childhood AML cases, confer a poor prognosis (Hollink et al, 2009b), other studies demonstrated that these mutations have no independent effect on outcome when FLT3 status is taken into account (Ho et al, 2010; Staffas et al, 2011). Recently, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs16754 was detected in 29% of patients and appeared to be an independent predictor of favourable outcome; however, the utility of this SNP in risk classification is unproven and needs to be prospectively evaluated (Ho et al, 2011a). Similar to WT1, the IDH1 and IDH2 genes contain mutations and SNPs that have been detected in adult and childhood AML (Marcucci et al, 2011; Damm et al, 2011; Ho et al, 2011b; Andersson et al, 2011). Although mutations occur in approximately 4% of cases and the rs11554137 SNP occurs in approximately 10%, these abnormalities do not appear to have independent prognostic significance. In addition, monosomal karyotypes; mutations of RUNX1, TET2, and DNMT3A; and expression levels of BAALC and ERG may have prognostic importance in adults, but the data are not sufficient to allow risk-group assignment on the basis of these factors in childhood AML (Marcucci et al, 2011; Staffas et al, 2011). However, recent studies suggest that high BAALC expression is an independent negative predictor of outcome (Staffas et al, 2011) and that high ERG expression may be prognostically important among patients with MLL gene rearrangements (Pigazzi et al, 2012).

Perhaps the most important clinical predictor of outcome in patients with AML is response to therapy, as assessed by MRD (Campana, 2008; Buccisano et al, 2012). MRD detection methods rely on leukaemia-specific features that distinguish residual leukaemia cells from normal haematopoietic precursors. Methods applicable to AML include RNA-based polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of leukaemia-specific gene fusions, quantitative analysis of WT1 expression, and flow cytometric detection of aberrant immunophenotypes (Campana, 2008). Although reverse transcript PCR (RT-PCR) detection of fusion transcripts is sensitive to a level of 0.01% to 0.001%, it can be used in only about 50% of cases. In addition, persistent expression of RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11 can be seen in patients who are in long-term remission. In contrast, the sensitivity of flow-based MRD assays is only 0.1% to 0.01%, but this technique can be applied to more than 90% of cases. Flow-based MRD detection has been used successfully by investigators from the COG (Sievers et al, 1996; Sievers et al, 2003), the BFM study group (Langebrake et al, 2006), St. Jude (Coustan-Smith et al, 2003; Rubnitz et al, 2010a), and the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group (DCOG) (van der Velden et al, 2010).

In one of the first studies of MRD in childhood AML, Sievers et al (2003) evaluated the impact of MRD on outcome among 252 patients treated on the Children’s Cancer Group (CCG)-2941 and 2961 trials. At the end of induction therapy, 16% of patients had detectable MRD (defined as ≥ 0.5% blasts) and were nearly five times more likely to experience relapse than patients who were MRD negative. In the BFM study, MRD measured after the first block of treatment was a better predictor of failure-free survival when compared to a risk classification schema based on FAB subtype, cytogenetics and blasts on day 15 by morphology in a multivariable analysis (Langebrake et al, 2006). However, the BFM investigators used MRD markers with variable sensitivities, some of which allowed the detection of leukaemic cells only if these were present at a level of 1% or higher. In the St. Jude AML02 trial (Rubnitz et al, 2010a), the presence of MRD after the first course of induction was significantly associated with an adverse outcome: the 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse was only 17% for the 128 patients without MRD but 39% for the 74 with MRD (p < 0.0001). The relapse rate was particularly high (49%) for patients with MRD > 1%, whereas patients with lower levels of MRD (0.1% to 1%) had a relapse rate of only 17%. Similar results were reported for 94 children with AML treated on the MRC AML12 and DCOG ANLL97 trials: 3-year relapse-free survival rates were 85%, 64%, and 14%, respectively, for patients who had MRD levels that were < 0.1%, 0.1% to 0.5%, and > 0.5% after the first course of therapy (TP2) (van der Velden et al, 2010). Although MRD at TP2 was an independent predictor of outcome in multivariate analysis, MRD levels at later time points in therapy has no prognostic significance.

In the near future, it is likely that a comprehensive algorithm based on genetic profiling and prospective monitoring of MRD will be used to individualize the intensity and, where possible, the components of therapy for patients with AML (Buccisano et al, 2012). In a recent study, Patel et al, 2012 performed a comprehensive mutational status of 18 genes in samples from 502 patients (398 in the test set; 104 in the validation set). They found at least one mutation in 97% of samples and demonstrated that FLT3-ITD, partial tandem duplication of the MLL gene, and mutations in ASXL1 and PHF6 were associated with a poor outcome, whereas mutations in CEBPA or IDH2 were associated with a superior survival. Moreover, the impact of high-dose daunorubicin during induction was strongly influenced by the genetic profile: only those patients with DNMT3A or NPM1 mutations or MLL translocations had higher survival rates when treated with high-dose compared to standard-dose daunorubicin. These findings suggest that rapid molecular profiling of relevant genes can potentially be used to make rational treatment decisions for patients with AML.

Although mutational analyses such as those described above (Patel et al, 2012), or even whole-genome sequencing, may become routine diagnostic tests in the future, they should be considered investigational at this time. We suggest that a minimum diagnostic evaluation of paediatric AML today should include analyses only of abnormalities for which there is strong evidence of prognostic or therapeutic relevance. We therefore believe that the standard workup should include conventional cytogenetic analysis, RT-PCR testing for the RUNX1-RUNX1T1 and CBFB-MYH11 fusion transcripts, mutational analysis of the FLT3, NPM1, and CEBPA genes, and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of MLL. For patients with karyotypic or FISH-based evidence of MLL gene rearrangements, RT-PCR should be performed for the common MLL fusions. Although the prognostic significance of the t(1;22) is not certain, we believe that patients with megakaryoblastic leukaemia should be tested for the presence of the RBM15-MKL1 fusion. Furthermore, we strongly believe that monitoring of MRD should be performed on every patient and should now be considered standard of care in the treatment of childhood AML.

Treatment of patients with newly diagnosed AML

Induction therapy

OS rates for children with AML have improved to greater than 60% in recent trials (Table II) (Tsukimoto et al, 2009; Rubnitz et al, 2010a; Gibson et al, 2011; Abrahamsson et al, 2011; Cooper et al, 2012; Creutzig et al, 2006). In the 1980s, the “3 + 7” regimen (daunorubicin, 45 mg/m2 per day for 3 days; cytarabine, 100 mg/m2 per day for 7 days) was demonstrated to induce remission in 60%-70% of AML patients and became the standard of care for induction therapy (Yates et al, 1982). Remission rates improved to greater than 80% in the 1990s, although it is not clear if this improvement was due the addition of other agents, such as thioguanine or etoposide (Hann et al, 1997) or to advances in supportive care. Efforts to improve remission and survival rates have included the addition of cladribine (Rubnitz et al, 2009), fludarabine (Lange et al, 2008), and gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Cooper et al, 2012); the replacement of daunorubicin with idarubicin or mitoxantrone (Creutzig et al, 2001a; O’Brien et al, 2002; Burnett et al, 2010; Gibson et al, 2011); intensification of cytarabine dose (Rubnitz et al, 2010a); and compression of the timing of therapy (Brisco et al, 1996). Although cladribine, fludarabine, and gemtuzumab ozogamicin were all tolerated, there is no evidence that the addition of these agents improved remission rates. Similarly, regimens that included daunorubicin, idarubicin, or mitoxantrone induced similar complete remission rates, as did those that used low-dose or high-dose cytarabine. Likewise, the use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after induction therapy neither decreased the incidence of infection or treatment-related mortality nor improved survival in the AML-BFM 98 trial (Creutzig et al, 2006; Lehrnbecher et al, 2007). Despite the lack of evidence that specific interventions improved remission induction rates, complete remission (CR) rates of approximately 90% have been reported on recent clinical trials (Table II).

Table II.

Results of recent clinical trials for paediatric acute myeloid leukaemia

| Study | Years of enrollment |

Eligible age (years) |

Number of patients |

CR ratea (%) |

Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRC AML10 | 1988-1995 | ≤ 14 | 341 | 92 | 7-year EFS: 48% 7-year OS: 56% |

Stevens et al, (1998) |

| LAME 89/91 | 1988-1996 | < 20 | 268 | 90 | 6-year EFS: 48% 6-year OS: 60% |

Perel et al, (2002)

Perel et al, (2005) |

| TCCSG M91-13, M96-14 |

1991-1998 | NA | 192 | 89 | 5-year EFS: 54% 5-year OS: 60% |

Tomizawa et al, (2007) |

| AML-BFM93 | 1993-1998 | < 18 | 471 | 82 | 5-year EFS: 50% 5-year OS: 58% |

Creutzig et al, (2001a)

Creutzig et al, (2001b) |

| NOPHO-AML93 | 1993-2000 | < 18 | 219 | 91 | 7-year EFS: 49% 7-year OS: 64% |

Lie et al, (2003) |

| POG9421 | 1995-1999 | ≤ 21 | 565 | 89 | 3-year EFS: 36% 3-year OS: 54% |

Gale et al, (2005) |

| MRC AML12 | 1995-2002 | < 16 | 529 | 92 | 10-year EFS: 54% 10-year OS: 64% |

Gibson et al, (2011) |

| CCG2961 | 1996-2002 | ≤ 21 | 901 | 88 | 5-year EFS: 42% 5-year OS: 52% |

Lange et al, (2008) |

| AML-BFM 98 | 1998-2003 | < 18 | 473 | 88 | 5-year EFS: 49% 5-year OS: 62% |

Creutzig et al, (2006)

Lehrnbecher et al, (2007) |

| AML99 | 2000-2002 | ≤ 18 | 240 | 95 | 5-year EFS: 62% 5-year OS: 76% |

Tsukimoto et al, (2009) |

| SJCRH AML02 | 2002-2008 | ≤ 21 | 216 | 94 | 3-year EFS: 63% 3-year OS: 71% |

Rubnitz et al, (2010a) |

| COG AAML0391 | 2003-2005 | ≤ 21 | 350 | 87 | 3-year EFS: 53% 3-year OS: 66% |

Cooper et al, (2012) |

| NOPHO-AML 2004 | 2004-2009 | ≤ 18 | 151 | 92 | 3-year EFS: 57% 3-year OS: 69% |

Abrahamsson et al, (2011) |

Abbreviations: BFM, Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster Study Group; CCG, Children’s Cancer Group; LAME, Leucámie Aiquë Myéloïde Enfant; MRC, Medical Research Council; NOPHO, Nordic Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology; POG, Pediatric Oncology Group; SJCRH, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital; TCCSG, Tokyo Children’s Cancer Study Group; CR, complete remission; EFS, event-free survival; OS, overall survival.

CR rate after 2 courses of induction therapy

High-dose daunorubicin has been compared with standard-dose daunorubicin in several randomized trials in adults with AML (Fernandez et al, 2009; Lowenberg et al, 2009; Ohtake et al, 2011). Although some studies showed improved remission or OS rates (Fernandez et al, 2009; Lowenberg et al, 2009), one (Ohtake et al, 2011) suggested that high-dose daunorubicin is not better than standard-dose idarubicin in terms of remission, relapse, or survival rates. In the AML-BFM 2004 trial, patients were randomized to receive high-dose liposomal daunorubicin (80 mg/m2/day x 3) versus standard-dose idarubicin (12 mg/m2/day x 3) in combination with cytarabine and etoposide during induction therapy (Creutzig et al, 2010). The overall results were excellent and there was a trend toward improved survival and less toxicity in patients who received liposomal daunorubicin.

Post-remission therapy

Clinical trials conducted by the CCG (Wells et al, 1993), the BFM group (Creutzig et al, 2001b), the Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) (Ravindranath et al, 1991), and the MRC (Stevens et al, 1998) demonstrated the benefit of intensive high-dose cytarabine-based post-remission chemotherapy in children with AML. These studies clearly showed that intensive post-remission therapy, administered as intensive chemotherapy, autologous HSCT, or allogeneic HSCT, improves outcome. By contrast, low-dose maintenance therapy may actually lower the survival rates (Perel et al, 2002; Wells et al, 1994). Trials performed during the past 15 years (Table II) have sought to determine the optimal duration of post-remission therapy, the benefit of new agents, the value of MRD monitoring, and the role of HSCT. However, like the interventions used to improve remission induction rates, many of the post-remission interventions have had only a modest impact on outcome. For example, relapse and OS rates were the same for children randomly assigned to receive four courses of chemotherapy and those assigned to receive five courses on the MRC AML12 trial (Gibson et al, 2011). The use of idarubicin, fludarabine, and interleukin-2 in the CCG2961 trial (Lange et al, 2008) did not improve outcome, nor did the addition of cyclosporine in the POG9421 study (Gale et al, 2005). Excellent supportive care, adaptation of therapy on the basis of each patient’s response, and the use of intensive chemotherapy or HSCT, all contributed to the outstanding results reported by the Japanese Childhood AML Cooperative Group (Tsukimoto et al, 2009), St. Jude (Rubnitz et al, 2010a), the COG (Lange et al, 2008), MRC (Gibson et al, 2011), BFM (Lehrnbecher et al, 2007), the NOPHO (Abrahamsson et al, 2011), and other cooperative groups (Table 2).

Attempts to improve results obtained with chemotherapy have included the use of autologous and allogeneic HSCT (Niewerth et al, 2010). Although autologous transplantation is rarely recommended for patients with AML, allogeneic HSCT is a reasonable option. However, the indications for this procedure and guidelines for selecting transplant candidates in first remission remain controversial (Niewerth et al, 2010). In the CCG 2891 trial (Woods et al, 2001), the use of HSCT resulted in a higher survival rate compared to chemotherapy (60% vs. 53%, p = 0.05), whereas in the MRC AML10 trial (Hann et al, 1997; Burnett et al, 2002), HSCT reduced the risk of relapse without leading to a statistically significant OS advantage (70% vs. 60%, p = 0.1). Conflicting conclusions have also been derived from retrospective studies of HSCT versus chemotherapy. In one such study (Horan et al, 2008), in which 1373 children with AML were treated with HSCT or chemotherapy on cooperative group trials, HSCT was associated with a lower incidence of relapse but a higher incidence of treatment-related mortality; in terms of OS, only patients with intermediate-risk AML benefited from HSCT. It is likely that differences in the intensity and efficacy of pre-transplant chemotherapy explain the discrepant conclusions derived from the aforementioned studies. Conflicting reports on the benefits of HSCT have led to a variety of recommendations. In general, study groups in the United States recommend HSCT for a larger proportion of patients than do the European groups (Horan et al, 2008; Niewerth et al, 2010). In fact, European investigators (Niewerth et al, 2010) concluded that in most cases of childhood AML, HSCT should not be used in first remission because the reduction in the risk of relapse is offset by increased treatment-related mortality, more severe late effects, and decreased salvage rates after HSCT. However, improvements in HSCT are leading to fewer short- and long-term side effects and greater benefits (Gooley et al, 2010; Horan et al, 2011; Leung et al, 2011). For example, there appears to be no difference in survival between patients who receive matched related donor versus matched unrelated donor HSCT (Saber et al, 2012). In addition, we recently reported (Leung et al, 2011) that among children with high-risk AML who were treated in the AML02 trial and underwent HSCT at our institution, the 5-year OS was 74% and did not differ according to donor source (sibling donor, 68%; unrelated donor, 74%; haploidentical donor, 77%). The improvements in outcome were attributed to better supportive care, more comprehensive human leucocyte antigen typing, and the selection of Killer Ig-like receptor (KIR)-mismatched donors when possible. It should be noted, however, that this study was not designed to compare the relative benefits of HSCT versus chemotherapy. In addition, the presence of detectable disease at the time of transplant was associated with an inferior survival. However, we recently reported that even for patients with positive MRD (0.01% to 5%), the 5-year OS estimate was 67% (compared to 80% for MRD-negative patients), suggesting that although MRD is an important predictor of outcome, it should not be considered a contraindication to HSCT (Leung et al, 2012).

Supportive care

Supportive care is critical in the management of AML, both at the time of initial diagnosis and during therapy (Molgaard-Hansen et al, 2010). Patients who present with leucocyte counts greater than 100 × 109/l are at risk of intracranial haemorrhage or respiratory insufficiency secondary to leucostasis (Inaba et al, 2008). All patients with hyperleucocytosis or with symptoms of leucostasis should immediately receive interventions to reduce the leukaemic burden, such as leukapheresis, exchange transfusion, hydroxycarbamide, or low-dose cytarabine.

Infectious complications remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality in children with AML (Sung et al, 2007; Alexander et al, 2012; Dvorak et al, 2012). Randomized, controlled trials demonstrated that prophylactic antibiotics are effective at reducing the incidence of bacterial infection in adults with cancer (Alexander et al, 2012), but similar studies are lacking in children. One retrospective study (Kurt et al, 2008) demonstrated that prophylactic use of cefepime or vancomycin and ciprofloxacin dramatically reduced the risk of bacterial infection in children with AML, suggesting that these or similar regimens are likely to be beneficial.

Disseminated fungal infections, most commonly caused by Candida and Aspergillus species, may be life-threatening in children with AML (Dvorak et al, 2012). On the basis of randomized, controlled trials of prophylactic antifungal therapy in adults with cancer studies, many paediatric oncologists recommend antifungal prophylaxis with voriconazole, posaconazole, micafungin, or caspofungin. Fluconazole and itraconazole are not ideal agents because they are less active against Aspergillus species and other moulds, whereas the broad activity and good tolerability of voriconazole and posaconazole make them attractive choices.

Late effects

As survival rates for AML have improved, it has become increasingly important to assess long-term survivors for late medical and social effects related to prior therapy. Encouraging results were reported by the NOPHO investigators, who found that AML survivors who had received only chemotherapy had similar rates of hospitalization and similar self-reported health experience scores, educational achievement, and employment compared to sibling controls (Molgaard-Hansen et al, 2011). However, among AML survivors who participated in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, 16% had severe or life-threatening medical conditions, compared to 5.8% of siblings, and a standardized mortality ratio (SMR) from heart disease of 9.1 (Mulrooney et al, 2008). Cardiac toxicity is even more prevalent among AML survivors who have received higher doses of anthracyclines; among 5-year AML survivors treated in Britain, the SMR for cardiac death was 27 (Reulen et al, 2010). And among cancer survivors who received greater than 360 mg/m2 anthracycline, the SMR for death from cardiac disease was 43.7 (Tukenova et al, 2010). Given that childhood AML protocols in the United States have used high doses of anthracyclines since 2002, it is crucial to carefully monitor all survivors for subclinical cardiotoxicity and develop interventions to prevent or treat this toxicity.

Special subgroups

Children with Down syndrome and AML have a favourable prognosis, with OS rates greater than 80%, and should be treated in cooperative group trials that are designed to minimize toxicity while maintaining high cure rates (Gamis, 2005; Taga et al, 2011). The excellent outcome has been at least partly attributed to increased levels of cystathionine-β-synthetase, a high frequency of cystathionine-β-synthetase polymorphisms, and decreased levels of cytidine deaminase in the blasts of patients with Down syndrome, all of which result in altered metabolism of cytarabine (Ge et al, 2006; Ge et al, 2005).

Approaches to the diagnosis, supportive care measures, and treatment of childhood acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) are similar to those in adults with APL, including the immediate initiation of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) followed by the continued use of ATRA with an anthracycline, and the inclusion of effective maintenance chemotherapy (Tallman & Altman, 2009; Sanz & Lo-Coco, 2011). The outcome for children with APL is excellent: among 107 paediatric patients enrolled on the AIDA (ATRA, idarubicin) 0493 trial, 89% are long-term survivors (Testi et al, 2005). In the European APL93 and APL2000 trials, adolescents (13-18 years) had a 5-year OS of rate of 94%, slightly better than that achieved by children less than 13 years (5-year OS 80%) (Bally et al, 2012). Arsenic trioxide (ATO) is effective as a single agent in children (Zhou et al, 2010) and adults (Ghavamzadeh et al, 2011; Mathews et al, 2010) with APL, and, when added to standard therapy, has been shown to improve outcome in adults (Powell et al, 2010). Ongoing trials for children with APL include the COG AAML0631 study, which incorporates ATO and reduces anthracycline exposure, and the International Consortium for Childhood APL Study 01.

Treatment of relapsed AML

AML recurs in 30% to 40% of patients and is associated with a poor prognosis; less than one-third of children with relapsed AML survive (Aladjidi et al, 2003; Wells et al, 2003; Rubnitz et al, 2007; Abrahamsson et al, 2007; Sander et al, 2010; Gorman et al, 2010). Bone marrow is the most common site of relapse, although isolated central nervous system relapses occur in approximately 5% of patients (Johnston et al, 2005). Considerations after relapse include the choice of chemotherapy for induction of second remission and the timing of HSCT, currently regarded as the only curative therapy for relapsed AML (Shenoy & Smith, 2008; Niewerth et al, 2010). Because many of the frontline regimens for AML include a total anthracycline dose exceeding 400 mg/m2, it is often necessary to administer non-anthracycline regimens upon relapse to prevent further cardiac toxicity. A partial list of agents, some of which are currently under investigation for use in patients with relapsed leukaemia, and others which are being studied in newly diagnosed patients, is provided in Table III and discussed further below

Table III.

Therapeutic agents under investigation for acute myeloid leukaemia

| Class | Agent(s) | Target |

|---|---|---|

| Deoxyadenosine analogue | Clofarabine | Ribonucleotide reductase, DNA polymerase, mitochondria |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Sorafenib, quizartinib, lestaurtinib, midostaurin, sunitinib |

Tyrosine kinase (eg, FLT3-ITD) |

| Demethylating agent | Azacitidine, decitabine | DNA methyltransferase |

| Proteosome inhibitor | Bortezomib | Proteosome |

| Histone deacetylase inhibitor | Valproic acid, vorinostat, panobinostat, depsipeptide |

Histone deacetylase |

| Farnesyltransferase inhibitor | Tipifarnib, lonafarnib | Ras, lamin A |

| Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor | Ruxolitinib, TG101348, CYT387 | JAK |

| Chemokine receptor (CXCR4) antagonist |

Plerixafor | CXCL12 (SDF1)/CXCR4 axis |

| Apoptosis inducer | Obatoclax, oblimersen | BCL2 |

| Angiogenesis inhibitor | Bevacizumab | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| Multi-drug resistance inhibitor | Cyclosporine, valspodar | P-glycoprotein |

| Lineage-specific antibody | Anti-CD33 (Mylotarg), −CD45, −CD66 | Lineage-specific antigen |

| Immune therapy | Natural killer cells, T cells | Leukaemia cells |

New Agents

Deoxyadenosine analogues

The nucleoside analogues cladribine, fludarabine, and clofarabine have little cardiac toxicity and are among the most active agents in relapsed AML. Deoxycytidine kinase converts these agents to their triphosphate forms, which inhibit ribonucleotide reductase, decrease de novo synthesis of deoxynucleotides, and decrease the feedback inhibition of deoxycytidine kinase. Clinical studies show that intracellular cytarabine triphosphate accumulates when cladribine, fludarabine, or clofarabine is given with cytarabine (Crews et al, 2002; Gandhi et al, 1993; Faderl et al, 2005). The combinations of cladribine plus cytarabine and fludarabine plus cytarabine have been shown to be effective in paediatric AML (Krance et al, 2001; Razzouk et al, 2001; Estey et al, 1994). In the setting of relapsed AML, the combination of fludarabine, cytarabine, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, with or without an anthracycline, has induced second remission rates of 58% to 78% (Aladjidi et al, 2003; Abrahamsson et al, 2007; Sander et al, 2010).

Clofarabine is a second-generation deoxyadenosine analogue that retains the favourable properties of cladribine and fludarabine and has single-agent activity in paediatric AML (Jeha et al, 2004; Jeha et al, 2009). The COG has recently completed a trial of clofarabine and cytarabine in children with relapsed AML and we are testing this combination with sorafenib in such patients (Inaba et al, 2011). The combination of clofarabine with cyclophosphamide and etoposide is also under investigation (Hijiya et al, 2009; Inaba et al, 2012).

It should be noted that although fludarabine, cladribine, and clofarabine are active in AML, there have not been any studies that demonstrate that any of these agents are more effective than cytarabine. Similarly, when given with cytarabine, each of these analogues can increase intracellular cytarabine triphosphate levels, but there is no evidence that these combinations are better than high-dose cytarabine alone. For example, in the AML-BFM 2004 trial, there were no significant differences in OS or event-free survival (EFS) between patients randomized to receive cytarabine/idarubicin or cytarabine/cladribine/idarubicin intensification (Creutzig et al, 2010).

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

AML cells frequently have aberrant receptor tyrosine kinase activity due to genetic alterations, such as FLT3-ITD, KIT mutations, and aberrations in downstream signalling pathways (Meshinchi & Appelbaum, 2009). Constitutive activation of one or more signalling pathways in AML cells is associated with a poor prognosis (Kornblau et al, 2006). However, whether FLT3-ITD has a causative role in leukaemogenesis and is thus a valid therapeutic target, or is simply a nonessential “passenger” mutation, has not been clear until recently. Smith et al (2012) have now provided strong evidence that FLT3 mutations can be “driver” lesions and thus rational targets to which inhibitors should be developed. Consequently, the signalling inhibitors lestaurtinib, midostaurin, quizartinib, and sorafenib are being tested for this application in adult and paediatric AML (Zhang et al, 2008; Levis et al, 2011; Ravandi et al, 2010; Zarrinkar et al, 2009).

The results of a Phase I/II study demonstrated that sorafenib could be safely combined with idarubicin and cytarabine in adults and produced a high rate of remission among patients with FLT3-ITD (Ravandi et al, 2010). However, a randomized trial of chemotherapy with or without lestaurtinib in adults with relapsed, FLT3-ITD-positive AML revealed no difference in CR or OS between the two arms (Levis et al, 2011). Possible explanations include the lack of FLT3 inhibition in 42% of patients who received lestaurtinib and the observation that relapse is often associated with high levels of FLT3 ligand, which may mitigate inhibition (Levis, 2011; Sato et al, 2011). Emerging data on quizartinib (AC220), which is now in clinical trials, suggest that it may be a more potent and selective inhibitor (Zarrinkar et al, 2009).

We recently evaluated the activity of sorafenib, given alone or in combination with cytarabine and clofarabine, in 12 children with refractory/relapsed leukaemia (Inaba et al, 2011). In this study, 7 days of treatment with single-agent sorafenib decreased blast percentages in 10 of 11 patients with AML. After combination chemotherapy, eight patients (5 FLT3-ITD and 3 wild-type FLT3) experienced either CR or CR with incomplete blood count recovery, while one (FLT3 wild-type AML) had a partial remission. Clinical trials, such as the St. Jude AML08 and the COG AAML1031 protocols, for newly diagnosed patients with AML now incorporate sorafenib for patients with FLT3-ITD. However, until the benefit of sorafenib or other FLT3 inhibitors has been established, these agents should only be used in the context of a clinical trial.

DNA modification

Dysregulation of epigenetic modification, including histone deacetylation and DNA methylation, is an important factor in the pathogenesis of AML (Quintas-Cardama et al, 2011; Godley & Le Beau, 2012). Aberrant activity of histone deacetylases (HDACs) and methyltransferases probably causes abnormal gene expression patterns in haematopoietic precursors that contribute to the differentiation arrest seen in AML (Lokken & Zeleznik-Le, 2012). A central role for epigenetic dysfunction in AML is supported by the observation of mutations and translocations in genes involved in these processes, such as TET2, DNMT3, IDH1, IDH2, and the histone H3K4 methyltransferase gene (MLL). These findings suggest that HDAC inhibitors and demethylating agents may have a prominent role in the treatment of AML (Godley & Le Beau, 2012). The HDAC inhibitor, vorinostat, and the hypomethylating agents, decitabine and 5-azacytidine, have shown promising activity in adults with myeloid malignancies (Garcia-Manero et al, 2006) and are currently being tested in combination with chemotherapy (Garcia-Manero et al, 2012). Recently, Harris et al (2012) demonstrated that the histone demethylase KDM1A was essential to the leukaemogenic properties of the MLL-MLLT3 (AF9)fusion protein and that inhibition of KDM1A reversed the differentiation arrest induced by the MLL fusion, suggesting that KDM1A may be a key therapeutic target in AML cases with MLL rearrangements.

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO, Mylotarg) is a humanized anti-CD33–calicheamicin conjugate that was shown to induce complete responses in about one-third of paediatric and adult patients with relapsed AML when given as a single agent (Sievers et al, 2001; Arceci et al, 2005; Zwaan et al, 2010) and in about half of paediatric patients who received it in combination with cytarabine (Brethon et al, 2008). Although it was approved for use in AML by the US Federal Drug Administration in 2000 (Bross et al, 2001), it was withdrawn in 2010 when an interim analysis of a randomized trial (SWOG [South Western Oncology Group] 106) in adults demonstrated an increased early death rate in the GO arm of the trial. However, two large studies (Burnett et al, 2011; Castaigne et al, 2012) strongly suggest that this agent may be beneficial in a subset of patients. In a study of 1113 patients randomly assigned to receive chemotherapy with or without the addition of GO, MRC investigators demonstrated that patients with favourable cytogenetics were highly likely to benefit from GO (Burnett et al, 2011). More recently, the results of a randomized trial of chemotherapy with or without fractionated, low-dose GO indicated that adults with AML who received this agent had lower relapse rates and higher EFS and OS rates than did those who received chemotherapy only (Castaigne et al, 2012). In addition, GO did not increase toxicity in either trial. By contrast, results of the NOPHO-AML 2004 trial, in which patients were randomized to receive post-consolidation GO or no further therapy, demonstrated that GO did not affect relapse or survival rates (Hasle et al, 2012). Together, the findings of these trials suggest that judicious use of GO in combination with chemotherapy may improve clinical outcome in selected subgroups of newly diagnosed patients and may also be a useful agent in the treatment of relapsed AML.

Plerixafor

Normal haematopoietic precursors, as well as leukaemia cells, interact with the bone marrow microenvironment through a variety of adhesion molecules and their corresponding ligands, such as the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its ligand, CXCL12 (Burger & Peled, 2009). It has been hypothesized that these interactions mediate drug resistance and that mobilization of leukaemic cells from the protective microenvironment may increase chemosensitivity (Burger & Peled, 2009). Plerixafor, a small molecule inhibitor of CXCR4, disrupts CXCR4-CXCL12 interactions, mobilizes AML cells, and increases sensitivity to conventional chemotherapy and to sorafenib, suggesting that it may provide a useful therapeutic approach (Zeng et al, 2009). A recent clinical trial (Uy et al, 2012) demonstrated that plerixafor, given in combination with mitoxantrone, etoposide, and cytarabine, was safe, did not cause hyperleucocytosis or delayed count recovery, and resulted in acceptable remission rates. As the investigators had postulated, plerixafor caused the mobilization of leukaemic blasts into the circulation; however, its effects were not selective: normal and leukaemic cells were equally mobilized. The apparent lack of toxicity to normal haematopoietic cells raises the possibility that plerixafor-induced mobilization may not lead to increased toxicity to leukaemic cells either. Further studies are required to determine the beneficial effects, if any, of plerixafor or other agents that disrupt the leukaemia microenvironment.

Immunotherapy

Although HSCT for children with AML in first remission is controversial, it is strongly recommended for all patients with relapsed or refractory AML (Shenoy & Smith, 2008). For patients who lack a matched-sibling donor, stem cells from a matched-unrelated donor, unrelated cord blood donor, or haploidentical donor are considered (Eapen et al, 2007; Shaw et al, 2010; Leung et al, 2011). Although the remission status before transplant is important, patients with persistent disease at the time of transplant have survived (Bunin et al, 2008; Duval et al, 2010; Leung et al, 2012).

The powerful antileukaemic effect of KIR-mismatched donor natural killer (NK) cells in the setting of allogeneic HSCT, first demonstrated by Ruggeri et al, (2002), has been observed in AML patients who undergo HSCT in first remission and after relapse (Giebel et al, 2003; Ruggeri et al, 2007). The complex regulation and classification of NK cells and their beneficial effects on relapse, engraftment, and infection were elegantly reviewed in a previous issue this journal (Leung, 2011).

There is growing interest in the use of allogeneic NK cells in the non-HSCT setting (Miller et al, 2005; Rubnitz et al, 2010b). To assess the safety and feasibility of this approach in children with AML, we performed a pilot study of low-dose immunosuppression followed by the infusion of purified, parental haploidentical NK cells (Rubnitz et al, 2010b). Toxicity was minimized by the use of a low-intensity regimen and a two-step isolation method (Iyengar et al, 2003; Leung et al, 2005) that provided highly purified NK cells with minimal contamination of T or B cells. All patients had transient engraftment, a significant expansion of KIR-mismatched NK cells, and minimal toxicity (Rubnitz et al, 2010b). These results suggest that mild conditioning followed by the infusion of haploidentical mismatched NK cells is a safe and potentially promising approach to reduce the risk of relapse, or to treat relapse, in patients with AML.

NK cell therapy may be augmented by a variety of methods, as reviewed by Leung (2011). For example, NK cells can be expanded and activated by exposure to a genetically modified K562 myeloid leukaemia cell line engineered to express a membrane-bound form of interleukin-15 and the ligand for the costimulatory molecule 4-1BB (Imai et al, 2005; Fujisaki et al, 2009). This method results in a 20-fold or greater expansion of NK cells, which are more cytotoxic than primary NK cells, regardless of the receptor-ligand interaction. We are currently testing this approach in patients with relapsed disease.

Conclusion

Recent insights into the molecular genetics and biology of AML have done much to clarify the complexity and often-daunting heterogeneity of this disease. Indeed, the ability to analyse the genetic and epigenetic aberrations in AML on a global basis is rapidly maturing and is expected to expand the repertoire of useful targets for personalized molecular medicine. We predict the development of more effective, less toxic treatment strategies for still-incurable subgroups of AML patients in the near future. However, the evaluation of such strategies will probably require large international collaborative studies to enrol adequate numbers of patients to which each therapy is directed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julie Groff for preparation of the figures, Xueyuan Cao for statistical assistance and John Gilbert for expert editorial review. This work was supported in part by Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant P30 CA021765-30 from the National Institutes of Health and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Authorship Contributions: JER and HI wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abrahamsson J, Clausen N, Gustafsson G, Hovi L, Jonmundsson G, Zeller B, Forestier E, Heldrup J, Hasle H. Improved outcome after relapse in children with acute myeloid leukaemia. British Journal of Haematology. 2007;136:229–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamsson J, Forestier E, Heldrup J, Jahnukainen K, Jonsson OG, Lausen B, Palle J, Zeller B, Hasle H. Response-guided induction therapy in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia with excellent remission rate. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:310–315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aladjidi N, Auvrignon A, Leblanc T, Perel Y, Benard A, Bordigoni P, Gandemer V, Thuret I, Dalle JH, Piguet C, Pautard B, Baruchel A, Leverger G. Outcome in children with relapsed acute myeloid leukemia after initial treatment with the French Leucemie Aique Myeloide Enfant (LAME) 89/91 protocol of the French Society of Pediatric Hematology and Immunology. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:4377–4385. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander S, Nieder M, Zerr DM, Fisher BT, Dvorak CC, Sung L. Prevention of bacterial infection in pediatric oncology: What do we know, what can we learn? Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2012;59:16–20. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson AK, Miller DW, Lynch JA, Lemoff AS, Cai Z, Pounds SB, Radtke I, Yan B, Schuetz JD, Rubnitz JE, Ribeiro RC, Raimondi SC, Zhang J, Mullighan CG, Shurtleff SA, Schulman BA, Downing JR. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in pediatric acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:1570–1577. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arceci RJ, Sande J, Lange B, Shannon K, Franklin J, Hutchinson R, Vik TA, Flowers D, Aplenc R, Berger MS, Sherman ML, Smith FO, Bernstein I, Sievers EL. Safety and efficacy of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in pediatric patients with advanced CD33+ acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:1183–1188. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachas C, Schuurhuis GJ, Hollink IH, Kwidama ZJ, Goemans BF, Zwaan CM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, De Bont ES, Reinhardt D, Creutzig U, de H,V, Assaraf YG, Kaspers GJ, Cloos J. High-frequency type I/II mutational shifts between diagnosis and relapse are associated with outcome in pediatric AML: implications for personalized medicine. Blood. 2010;116:2752–2758. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balgobind BV, Raimondi SC, Harbott J, Zimmermann M, Alonzo TA, Auvrignon A, Beverloo HB, Chang M, Creutzig U, Dworzak MN, Forestier E, Gibson B, Hasle H, Harrison CJ, Heerema NA, Kaspers GJ, Leszl A, Litvinko N, Nigro LL, Morimoto A, Perot C, Pieters R, Reinhardt D, Rubnitz JE, Smith FO, Stary J, Stasevich I, Strehl S, Taga T, Tomizawa D, Webb D, Zemanova Z, Zwaan CM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. Novel prognostic subgroups in childhood 11q23/MLL-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia: results of an international retrospective study. Blood. 2009;114:2489–2496. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balgobind BV, Zwaan CM, Pieters R, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. The heterogeneity of pediatric MLL-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:1239–1248. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bally C, Fadlallah J, Leverger G, Bertrand Y, Robert A, Baruchel A, Guerci A, Recher C, Raffoux E, Thomas X, Leblanc T, Idres N, Cassinat B, Vey N, Chomienne C, Dombret H, Sanz M, Fenaux P, Ades L. Outcome of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL) in Children and Adolescents: An Analysis in Two Consecutive Trials of the European APL Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:1641–1646. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brethon B, Yakouben K, Oudot C, Boutard P, Bruno B, Jerome C, Nelken B, de LL, Bertrand Y, Dalle JH, Chevret S, Leblanc T, Baruchel A. Efficacy of fractionated gemtuzumab ozogamicin combined with cytarabine in advanced childhood myeloid leukaemia. British Journal of Haematology. 2008;143:541–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisco J, Hughes E, Neoh SH, Sykes PJ, Bradstock K, Enno A, Szer J, McCaul K, Morley AA. Relationship between minimal residual disease and outcome in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1996;87:5251–5256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bross PF, Beitz J, Chen G, Chen XH, Duffy E, Kieffer L, Roy S, Sridhara R, Rahman A, Williams G, Pazdur R. Approval summary: gemtuzumab ozogamicin in relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Clinical Cancer Research. 2001;7:1490–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, McIntyre E, Rau R, Meshinchi S, Lacayo N, Dahl G, Alonzo TA, Chang M, Arceci RJ, Small D. The incidence and clinical significance of nucleophosmin mutations in childhood AML. Blood. 2007;110:979–985. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-076604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccisano F, Maurillo L, Del Principe MI, Del PG, Sconocchia G, Lo-Coco F, Arcese W, Amadori S, Venditti A. Prognostic and therapeutic implications of minimal residual disease detection in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;119:332–341. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-363291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunin NJ, Davies SM, Aplenc R, Camitta BM, DeSantes KB, Goyal RK, Kapoor N, Kernan NA, Rosenthal J, Smith FO, Eapen M. Unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation for children with acute myeloid leukemia beyond first remission or refractory to chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:4326–4332. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger JA, Peled A. CXCR4 antagonists: targeting the microenvironment in leukemia and other cancers. Leukemia. 2009;23:43–52. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett AK, Wheatley K, Goldstone AH, Stevens RF, Hann IM, Rees JH, Harrison G. The value of allogeneic bone marrow transplant in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia at differing risk of relapse: results of the UK MRC AML 10 trial. British Journal of Haematology. 2002;118:385–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett AK, Hills RK, Milligan DW, Goldstone AH, Prentice AG, McMullin MF, Duncombe A, Gibson B, Wheatley K. Attempts to optimize induction and consolidation treatment in acute myeloid leukemia: results of the MRC AML12 trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:586–595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett AK, Hills RK, Milligan D, Kjeldsen L, Kell J, Russell NH, Yin JA, Hunter A, Goldstone AH, Wheatley K. Identification of patients with acute myeloblastic leukemia who benefit from the addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin: results of the MRC AML15 trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:369–377. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.4310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campana D. Status of minimal residual disease testing in childhood haematological malignancies. British Journal of Haematology. 2008;143:481–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaigne S, Pautas C, Terre C, Raffoux E, Bordessoule D, Bastie JN, Legrand O, Thomas X, Turlure P, Reman O, de RT, Gastaud L, de GN, Contentin N, Henry E, Marolleau JP, Aljijakli A, Rousselot P, Fenaux P, Preudhomme C, Chevret S, Dombret H. Effect of gemtuzumab ozogamicin on survival of adult patients with de-novo acute myeloid leukaemia (ALFA-0701): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2012;379:1508–1516. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TM, Franklin J, Gerbing RB, Alonzo TA, Hurwitz C, Raimondi SC, Hirsch B, Smith FO, Mathew P, Arceci RJ, Feusner J, Iannone R, Lavey RS, Meshinchi S, Gamis A. AAML03P1, a pilot study of the safety of gemtuzumab ozogamicin in combination with chemotherapy for newly diagnosed childhood acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2012;118:761–769. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coustan-Smith E, Ribeiro RC, Rubnitz JE, Razzouk BI, Pui CH, Pounds S, Andreansky M, Behm FG, Raimondi SC, Shurtleff SA, Downing JR, Campana D. Clinical significance of residual disease during treatment in childhood acute myeloid leukaemia. British Journal of Haematology. 2003;123:243–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutzig U, Ritter J, Zimmermann M, Hermann J, Gardner H, Sawatzki DB, Niemeyer CM, Schwabe D, Selle B, Boos J, Kuhl J, Feldges A. Idarubicin improves blast cell clearance during induction therapy in children with AML: results of study AML-BFM 93. AML-BFM Study Group. Leukemia. 2001a;15:348–354. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutzig U, Ritter J, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt D, Hermann J, Berthold F, Henze G, Jurgens H, Kabisch H, Havers W, Reiter A, Kluba U, Niggli F, Gadner H. Improved treatment results in high-risk pediatric acute myeloid leukemia patients after intensification with high-dose cytarabine and mitoxantrone: results of Study Acute Myeloid Leukemia-Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster 93. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001b;19:2705–2713. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.10.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutzig U, Zimmermann M, Lehrnbecher T, Graf N, Hermann J, Niemeyer CM, Reiter A, Ritter J, Dworzak M, Stary J, Reinhardt D. Less toxicity by optimizing chemotherapy, but not by addition of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in children and adolescents with acute myeloid leukemia: results of AML-BFM 98. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:4499–4506. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutzig U, Zimmerman M, Dworzak M, Bourquin JP, Neuhoff C, Sander A, Stary J, Reinhardt D. Study AML-BFM 2004: Improved survival in childhood acute myeloid leukemia without increased toxicity. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2010;116:181. [Google Scholar]

- Crews KR, Gandhi V, Srivastava DK, Razzouk BI, Tong X, Behm FG, Plunkett W, Raimondi SC, Pui CH, Rubnitz JE, Stewart CF, Ribeiro RC. Interim comparison of a continuous infusion versus a short daily infusion of cytarabine given in combination with cladribine for pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:4217–4224. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damm F, Thol F, Hollink I, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt K, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Zwaan CM, de H,V, Creutzig U, Klusmann JH, Krauter J, Heuser M, Ganser A, Reinhardt D, Thiede C. Prevalence and prognostic value of IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in childhood AML: a study of the AML-BFM and DCOG study groups. Leukemia. 2011;25:1704–1710. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dezern AE, Sung A, Kim S, Smith BD, Karp JE, Gore SD, Jones RJ, Fuchs E, Luznik L, McDevitt M, Levis M. Role of allogeneic transplantation for FLT3/ITD acute myeloid leukemia: outcomes from 133 consecutive newly diagnosed patients from a single institution. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2011;17:1404–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Ley TJ, Larson DE, Miller CA, Koboldt DC, Welch JS, Ritchey JK, Young MA, Lamprecht T, McLellan MD, McMichael JF, Wallis JW, Lu C, Shen D, Harris CC, Dooling DJ, Fulton RS, Fulton LL, Chen K, Schmidt H, Kalicki-Veizer J, Magrini VJ, Cook L, McGrath SD, Vickery TL, Wendl MC, Heath S, Watson MA, Link DC, Tomasson MH, Shannon WD, Payton JE, Kulkarni S, Westervelt P, Walter MJ, Graubert TA, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, DiPersio JF. Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2012;481:506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature10738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval M, Klein JP, He W, Cahn JY, Cairo M, Camitta BM, Kamble R, Copelan E, de LM, Gupta V, Keating A, Lazarus HM, Litzow MR, Marks DI, Maziarz RT, Rizzieri DA, Schiller G, Schultz KR, Tallman MS, Weisdorf D. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for acute leukemia in relapse or primary induction failure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:3730–3738. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.8852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak CC, Fisher BT, Sung L, Steinbach WJ, Nieder M, Alexander S, Zaoutis TE. Antifungal prophylaxis in pediatric hematology/oncology: New choices & new data. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2012;59:21–26. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Zhang MJ, Stevens C, Kurtzberg J, Scaradavou A, Loberiza FR, Champlin RE, Klein JP, Horowitz MM, Wagner JE. Outcomes of transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood and bone marrow in children with acute leukaemia: a comparison study. Lancet. 2007;369:1947–1954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60915-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppert K, Takenaka K, Lechman ER, Waldron L, Nilsson B, van GP, Metzeler KH, Poeppl A, Ling V, Beyene J, Canty AJ, Danska JS, Bohlander SK, Buske C, Minden MD, Golub TR, Jurisica I, Ebert BL, Dick JE. Stem cell gene expression programs influence clinical outcome in human leukemia. Nature Medicine. 2011;17:1086–1093. doi: 10.1038/nm.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estey E, Thall P, Andreeff M, Beran M, Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Escudier S, Robertson LE, Koller C, Kornblau S. Use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor before, during, and after fludarabine plus cytarabine induction therapy of newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes: comparison with fludarabine plus cytarabine without granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1994;12:671–678. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faderl S, Gandhi V, O’Brien S, Bonate P, Cortes J, Estey E, Beran M, Wierda W, Garcia-Manero G, Ferrajoli A, Estrov Z, Giles FJ, Du M, Kwari M, Keating M, Plunkett W, Kantarjian H. Results of a phase 1-2 study of clofarabine in combination with cytarabine (ara-C) in relapsed and refractory acute leukemias. Blood. 2005;105:940–947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez HF, Sun Z, Yao X, Litzow MR, Luger SM, Paietta EM, Racevskis J, Dewald GW, Ketterling RP, Bennett JM, Rowe JM, Lazarus HM, Tallman MS. Anthracycline dose intensification in acute myeloid leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361:1249–1259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisaki H, Kakuda H, Shimasaki N, Imai C, Ma J, Lockey T, Eldridge P, Leung WH, Campana D. Expansion of highly cytotoxic human natural killer cells for cancer cell therapy. Cancer Research. 2009;69:4010–4017. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale RE, Hills R, Pizzey AR, Kottaridis PD, Swirsky D, Gilkes AF, Nugent E, Mills KI, Wheatley K, Solomon E, Burnett AK, Linch DC, Grimwade D. Relationship between FLT3 mutation status, biologic characteristics, and response to targeted therapy in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:3768–3776. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamis AS. Acute myeloid leukemia and Down syndrome evolution of modern therapy--state of the art review. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2005;44:13–20. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi V, Estey E, Keating MJ, Plunkett W. Fludarabine potentiates metabolism of cytarabine in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia during therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11:116–124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian HM, Sanchez-Gonzalez B, Yang H, Rosner G, Verstovsek S, Rytting M, Wierda WG, Ravandi F, Koller C, Xiao L, Faderl S, Estrov Z, Cortes J, O’Brien S, Estey E, Bueso-Ramos C, Fiorentino J, Jabbour E, Issa JP. Phase 1/2 study of the combination of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine with valproic acid in patients with leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:3271–3279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-009142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Manero G, Tambaro FP, Bekele NB, Yang H, Ravandi F, Jabbour E, Borthakur G, Kadia TM, Konopleva MY, Faderl S, Cortes JE, Brandt M, Hu Y, McCue D, Newsome WM, Pierce SR, de LM, Kantarjian HM. Phase II Trial of Vorinostat With Idarubicin and Cytarabine for Patients With Newly Diagnosed Acute Myelogenous Leukemia or Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:2204–2210. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Stout ML, Tatman DA, Jensen TL, Buck S, Thomas RL, Ravindranath Y, Matherly LH, Taub JW. GATA1, cytidine deaminase, and the high cure rate of Down syndrome children with acute megakaryocytic leukemia. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97:226–231. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Dombkowski AA, Lafiura KM, Tatman D, Yedidi RS, Stout ML, Buck SA, Massey G, Becton DL, Weinstein HJ, Ravindranath Y, Matherly LH, Taub JW. Differential gene expression, GATA1 target genes, and the chemotherapy sensitivity of Down syndrome megakaryocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:1570–1581. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber JM, Smith BD, Ngwang B, Zhang H, Vala MS, Morsberger L, Galkin S, Collector MI, Perkins B, Levis MJ, Griffin CA, Sharkis SJ, Borowitz MJ, Karp JE, Jones RJ. A clinically relevant population of leukemic CD34+ Blood. 2012;119:3571–3577. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-364182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavamzadeh A, Alimoghaddam K, Rostami S, Ghaffari SH, Jahani M, Iravani M, Mousavi SA, Bahar B, Jalili M. Phase II study of single-agent arsenic trioxide for the front-line therapy of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:2753–2757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson BE, Webb DK, Howman AJ, de Graaf SS, Harrison CJ, Wheatley K. Results of a randomized trial in children with Acute Myeloid Leukaemia: medical research council AML12 trial. British Journal of Haematology. 2011;155:366–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel S, Locatelli F, Lamparelli T, Velardi A, Davies S, Frumento G, Maccario R, Bonetti F, Wojnar J, Martinetti M, Frassoni F, Giorgiani G, Bacigalupo A, Holowiecki J. Survival advantage with KIR ligand incompatibility in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from unrelated donors. Blood. 2003;102:814–819. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goardon N, Marchi E, Atzberger A, Quek L, Schuh A, Soneji S, Woll P, Mead A, Alford KA, Rout R, Chaudhury S, Gilkes A, Knapper S, Beldjord K, Begum S, Rose S, Geddes N, Griffiths M, Standen G, Sternberg A, Cavenagh J, Hunter H, Bowen D, Killick S, Robinson L, Price A, Macintyre E, Virgo P, Burnett A, Craddock C, Enver T, Jacobsen SE, Porcher C, Vyas P. Coexistence of LMPP-like and GMP-like leukemia stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley LA, Le Beau MM. The histone code and treatments for acute myeloid leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366:960–961. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1113401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, Hingorani S, Sorror ML, Boeckh M, Martin PJ, Sandmaier BM, Marr KA, Appelbaum FR, Storb R, McDonald GB. Reduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:2091–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman MF, Ji L, Ko RH, Barnette P, Bostrom B, Hutchinson R, Raetz E, Seibel NL, Twist CJ, Eckroth E, Sposto R, Gaynon PS, Loh ML. Outcome for children treated for relapsed or refractory acute myelogenous leukemia (rAML): a Therapeutic Advances in Childhood Leukemia (TACL) Consortium study. Pediatric Blood and Cancer. 2010;55:421–429. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade D, Walker H, Oliver F, Wheatley K, Harrison C, Harrison G, Rees J, Hann I, Stevens R, Burnett A, Goldstone A. The importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome in AML: analysis of 1,612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10 trial. The Medical Research Council Adult and Children’s Leukaemia Working Parties. Blood. 1998;92:2322–2333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman ML, Rossi RM, Neelakantan S, Li X, Corbett CA, Hassane DC, Becker MW, Bennett JM, Sullivan E, Lachowicz JL, Vaughan A, Sweeney CJ, Matthews W, Carroll M, Liesveld JL, Crooks PA, Jordan CT. An orally bioavailable parthenolide analog selectively eradicates acute myelogenous leukemia stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 2007a;110:4427–4435. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman ML, Li X, Corbett CA, Rossi RM, Bushnell T, Liesveld JL, Hebert J, Young F, Jordan CT. Rapid and selective death of leukemia stem and progenitor cells induced by the compound 4-benzyl, 2-methyl, 1,2,4-thiadiazolidine, 3,5 dione (TDZD-8) Blood. 2007b;110:4436–4444. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-088815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haferlach T, Kohlmann A, Klein HU, Ruckert C, Dugas M, Williams PM, Kern W, Schnittger S, Bacher U, Loffler H, Haferlach C. AML with translocation t(8;16)(p11;p13) demonstrates unique cytomorphological, cytogenetic, molecular and prognostic features. Leukemia. 2009;23:934–943. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann IM, Stevens RF, Goldstone AH, Rees JK, Wheatley K, Gray RG, Burnett AK. Randomized comparison of DAT versus ADE as induction chemotherapy in children and younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Results of the Medical Research Council’s 10th AML trial (MRC AML10). Adult and Childhood Leukaemia Working Parties of the Medical Research Council. Blood. 1997;89:2311–2318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris WJ, Huang X, Lynch JT, Spencer GJ, Hitchin JR, Li Y, Ciceri F, Blaser JG, Greystoke BF, Jordan AM, Miller CJ, Ogilvie DJ, Somervaille TC. The Histone Demethylase KDM1A Sustains the Oncogenic Potential of MLL-AF9 Leukemia Stem Cells. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:473–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison C, HIlls R, Moorman AV, Grimwade D, Hann I, Webb D, Wheatley K, de Graaf SS, van den Berg E, Burnett A, Gibson B. Cytogenetics of Childhood Acute Myeloid Leukemia: United Kingdom Medical Research Council Treatment Trials AML 10 and 12. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:2674–2681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasle H, Alonzo TA, Auvrignon A, Behar C, Chang M, Creutzig U, Fischer A, Forestier E, Fynn A, Haas OA, Harbott J, Harrison CJ, Heerema NA, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Kaspers GJ, Locatelli F, Noellke P, Polychronopoulou S, Ravindranath Y, Razzouk B, Reinhardt D, Savva NN, Stark B, Suciu S, Tsukimoto I, Webb DK, Wojcik D, Woods WG, Zimmermann M, Niemeyer CM, Raimondi SC. Monosomy 7 and deletion 7q in children and adolescents with acute myeloid leukemia: an international retrospective study. Blood. 2007;109:4641–4647. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasle H, Abrahamsson J, Forestier E, Ha SY, Heldrup J, Jahnukainen K, Jonsson OG, Lausen B, Palle J, Zeller B. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin as postconsolidation therapy does not prevent relapse in children with AML: results from NOPHO-AML 2004. Blood. 2012;120:978–984. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-416701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijiya N, Gaynon P, Barry E, silverman l., Thomson B, Chu R, Cooper T, Kadota R, Rytting M, Steinherz P, Shen V, Jeha S, Abichandani R, Carroll WL. A multi-center phase I study of clofarabine, etoposide and cyclophosphamide in combination in pediatric patients with refractory or relapsed acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:2259–2264. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]