Abstract

Background

The recognition of the importance of femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI) as a potential cause of hip pain has been stimulated by major efforts to salvage hip joints by reconstruction to prevent or delay the need for replacement. A previous review addressed the nature of FAI, the various types, and how to make the diagnosis. When FAI occurs, the structure between the femur and acetabular rim, the labrum, is initially impinged upon and subsequently injured.

Method

Injury to the labrum should be recognized when treating the osseous causes of FAI. Preserving or recovering labral function, enhancing hip stability and protecting the articular surface, is critical to restoring the hip to normal or near-normal mechanical and physiologic function. The present review collected the varied essential information about the labrum in a succinct manner, independent of treatment algorithms.

Results/conclusion

Advanced knowledge of the labrum is presented, including the anatomy, circulation, histology, embryology, and neurology, as well as how the labrum tears, the types of tears, and how to make the diagnosis. The advantages and limitations of diagnostic magnetic resonance techniques are discussed, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), indirect magnetic resonance arthrography (i-MRA), and direct magnetic resonance arthrography (d-MRA). The review recognizes the complexity of the labrum and provides a greater understanding of how the labrum is capable of stabilizing the joint and protecting the articular surface of the hip. This information will act as a guide in developing treatment plans when treating FAI.

Keywords: Labrum, Magnetic resonance imaging, MRI, Magnetic resonance arthrography, MRA, Consolidation

Introduction

The recognition of the importance of femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI) as a potential cause of hip pain and degenerative arthritis has resulted in efforts to prevent or delay, through reconstruction, the need for replacement.

When FAI occurs, the structure between the femur and acetabular rim, the labrum, is initially impinged upon and subsequently injured. This threatens the primary functions of the labrum, namely, enhancing hip stability and protecting the articular surface. Labral pathology should be treated in a manner to preserve these functions. Not doing so can lead to osteoarthritis. The diagnosis of FAI was the subject of our recent paper [1].

Surgical procedures, both arthroscopic and open, that are directed to preventing and/or correcting the effect of FAI, need to address the labral injuries, as well as the osseous problems [2]. Understanding how to best treat the labrum and the various causes of FAI requires further knowledge of the labrum, namely, its anatomy, circulation, histology, embryology, and neurology, as well as how the labrum tears and the types of tears. The acetabular pathology was extensively discussed previously. How cam impingement from proximal femoral pathology injures the labrum is complex and deserves further clarification. It is important to know how the diagnosis, character, and location of labral tears are made using current imaging techniques. Collectively, this information will increase the understanding of the labrum, awareness of how the labrum enhances stability and protects the articular surface, and how it is vulnerable to injury.

The intent of this article is to collect this varied essential information about the labrum in one succinct review, independent of treatment algorithms.

Labral anatomy

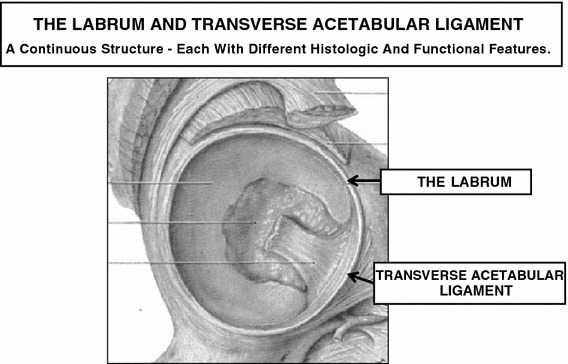

The anatomy of the labrum is unique. The labrum, also known as the cotyloid ligament, and the transverse acetabular ligament form a contiguous structure surrounding the acetabulum, or cotyloid fossa [3] (Fig. 1). The labrum is a fibro-cartilaginous structure attached to the edge of the acetabulum in a relatively secure manner. The transverse acetabular ligament is fixed firmly to the two pillars of the acetabular notch. Hip stability results from these two continuous structures encompassing more than half of the femoral head, so to speak, going “over” or lateral to the “equator” of the femoral head.

Fig. 1.

The labrum and transverse ligament are a continuous structure (modified with permission from Grant [3], Fig. 261)

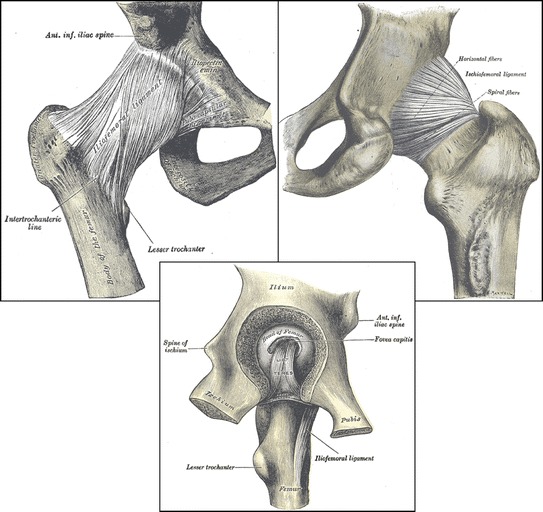

Together, these two structures are themselves surrounded, in turn, by the capsular ligaments, the iliofemoral, ischiofemoral, and pubocapsular ligaments [4] (Fig. 2). The ligamentum teres femoris arises from the acetabular pillars and the transverse acetabular ligament.

Fig. 2.

The pubocapsular, iliofemoral, and ischiofemoral ligaments. The ligament teres femoris arises from the pillars to the acetabular notch and the transverse acetabular ligament (modified with permission from Gray [4]: (a) p. 312, Fig. 336; (b) p. 313, Fig. 337; (c) p. 314, Fig. 338)

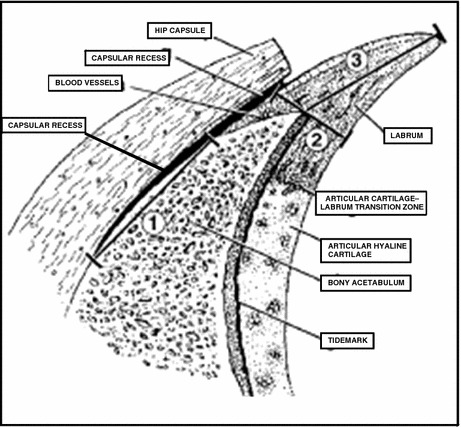

The labrum is separated from the capsule by the capsular recess. It merges on the capsular side with the bony acetabulum and on the articular side with the acetabular hyaline cartilage [5] (Fig. 3). The inner layer, on the articular side, is formed as a result of compressive and shear forces. The outer layer, on the capsular side, is comprised of dense connective tissue formed under tension stress [6].

Fig. 3.

The structure of the labrum. Note the capsular recess (modified with permission from Seldes et al. [5], Fig. 1)

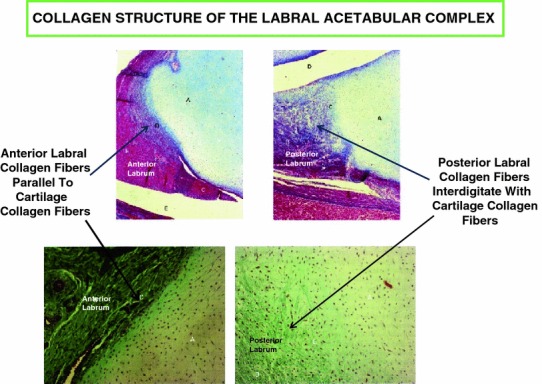

The attachment of the collagen fibers of the labrum to the acetabulum is different anteriorly and posteriorly [7]. The anterior collagen fibers of the labrum are parallel to those of the bony edge. This attachment is, thus, easily subject to separation from shear forces. Posteriorly, the fibers attach perpendicular to the edge and merge with the collagen fibers of the bony edge and, thus, are resistant to shear [7] (Fig. 4). Regardless of the location of labral tears or the extent and direction of forces upon the labrum, this instability of the attachment of the anterior labrum makes it significantly less resistant to shear forces. Interestingly, embryological studies reveal that initially, the anterior labrum extends between the femoral head and acetabulum [7] (Fig. 5). With time and motion, this extension “wears” away.

Fig. 4.

Collagen fiber attachment of the anterior and posterior labrum (modified with permission from Cashin et al. [7], Figs. 2ab and 3ab)

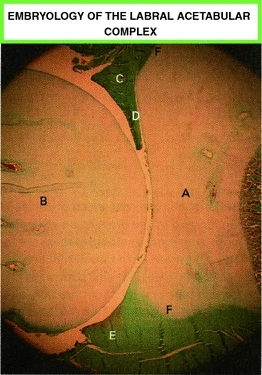

Fig. 5.

Embryology of the labral acetabular complex. Fetal hip at term. (A) acetabulum, (B) femur, (C) anterior labrum, (D) intra-articular projection, (E) posterior labrum (note that there is no intra-articular projection), and (F) acetabular labrum transition zone (modified with permission from Cashin et al. [7], Fig. 1)

Circulation

It is seldom recognized that a ring of circulation surrounds the hip, supplying the labrum circumferentially. The labral circulation is intimately interconnected to that of the hip as a whole, i.e., the acetabulum, the capsule, the femoral head and neck, and the adjacent soft tissue structures (Fig. 6). These structures are supplied primarily by the superior and inferior gluteal arteries and further supported by connection to the primary circulation to the femoral head, namely, the medial and lateral circumflex arteries and their cervical and epiphyseal branches (as described by Chung [8]). The gluteal vessels, located posteriorly, originate from the internal iliac artery. The medial and lateral circumflex arteries come, respectively, from the common and deep femoral arteries, which originate anteriorly from the external iliac artery [9]. The anterior and posterior origin of the labral circulation is thus established.

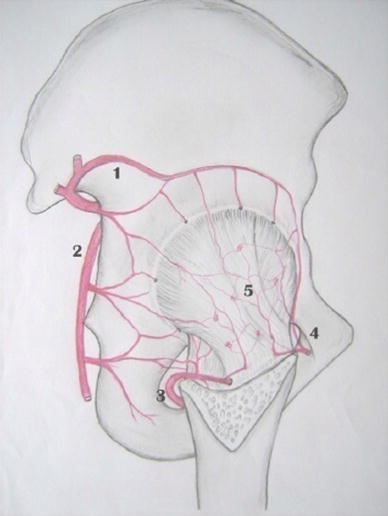

Fig. 6.

The (1) superior and (2) inferior gluteal arteries, the (3) medial and (4) lateral circumflex arteries contribute to the retinaculum (5), which supplies the labrum (reproduced with permission from Kalhor et al. [9], Fig. 8)

The first perforating branch of the deep femoral artery extends proximally under the quadratus femoris muscle, giving off a branch to that muscle, then anastamosing with the medial femoral circumflex behind the short rotators of the hip, progressing deep to join in supplying the capsule, labrum, and hip. It further extends proximally, joining the gluteal vessels completing the cruciate anastamosis. The ring then continues proximally. The superior gluteal artery extends under the gluteus minimus and tensor fascia lata muscles to connect anteriorly with the lateral femoral circumflex artery. The capsule, labrum, and acetabulum are supplied by the retinacular and perforating branches of these vessels (Fig. 6). The terminal vascular supply to the labrum is by retinacular vessels arising mainly from the superior and inferior gluteal vessels [9] (Fig. 7). The continuous connection of these four vessels through this cruciate anastamosis, well demonstrated recently by Grose et al. [10], recognizes this protection to the hip against vascular damage. Thus, by this described redundancy, the circulation of the anterior and posterior labrum, the capsule, and the osseous structures of the hip is reasonably assured.

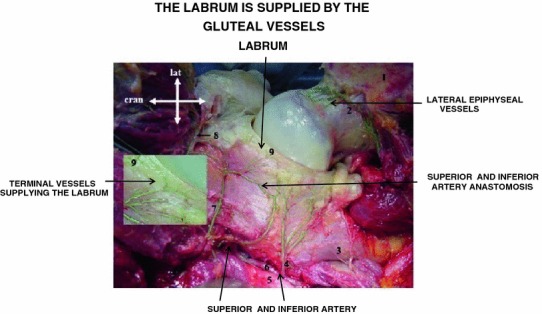

Fig. 7.

The labrum and capsule are supplied primarily by the superior and inferior gluteal arteries. The terminal branches of the capsular retinaculum are clearly demonstrated (modified with permission from Kalhor et al. [9], Fig. 6)

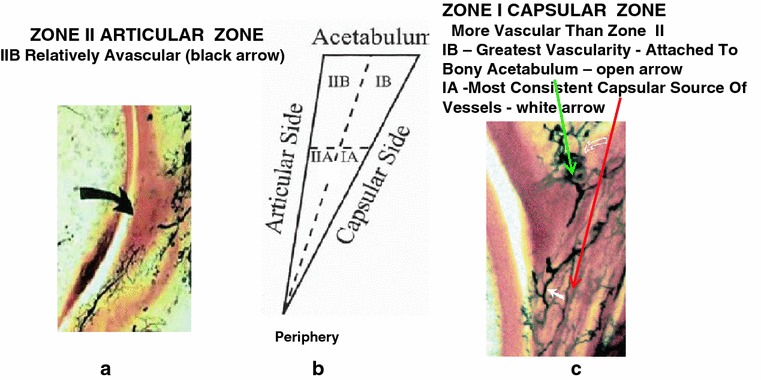

The study by Kelly et al. [11] describes the internal circulation of the labrum (Fig. 8). In describing this circulation, the labrum is divided into the half closest to the articular surface, Zone II, and the half on the capsular side, Zone I. The part of the capsular side of the labrum closest to the bony acetabular rim, Zone IB (green arrow and open arrow), is supplied by the circulation from that bone, which is the main source of labral circulation. The periphery of the capsular side of the labrum, Zone IA (red arrow and white arrow), is supplied by the capsular circulation. This same capsular circulation also supplies the periphery of the articular side of the labrum, Zone IIA. The articular part of the labrum closest to and merging with the hyaline articular cartilage, Zone IIB (black arrow), is relatively avascular.

Fig. 8.

The labrum zones of circulation: a Zone II—inner or articular side and c Zone I—outer or capsular side. Each of these is then divided into the peripheral part, IA and IIA, and the part closest to the acetabular rim, IB and IIB. The main vascular source is from the bony rim that primarily supplies Zone IB, the capsular side of the labrum closest to the rim (green arrow and open arrow). From there, the circulation extends to the periphery, to the peripheral capsular Zone IA (red arrow and white arrow). Through this peripheral capsular side, Zone IA, the peripheral articular side, Zone IIA is supplied. The inner articular side, merging with the articular cartilage, Zone IIB is relatively avascular (black arrow) (modified with permission from Kelly et al. [11]: (a) p. 9, Fig. 6; (b) p. 6, Fig. 3A; (c) p. 10, Fig. 7)

How does the labrum tear?

As stated, in instances of FAI, the labrum is in the middle, the object impinged upon, the victim, so to speak, of the impingement. Labral damage results from abnormalities on the acetabular (pincer) and/or femoral side (cam) of the hip. It occurs on the femoral side, either in part or entirely, from a retroverted femur or abnormal femoral head–neck junction striking the retroverted or deep (coxa profunda or protrusio acetabuli) acetabulum. However, this does not really explain how and where the impingement occurs. In the previous article, dealing with the diagnosis of FAI [1], the acetabular abnormalities causing impingement and, thus, labral damage were discussed extensively and will not be repeated, nor will the extra-articular causes of impingement be discussed, as such causes were referenced in the FAI article. However, in that article, cam impingement was dealt with in a limited manner. Basic diagnostic understanding of cam was described. However, the manner in which the three-dimensional (3D) characteristics of the proximal femur relate to motion of the hip was specifically not discussed, nor was the how, where, and extent of labral tears. It was intended that this more extensive discussion of cam be considered in the current review when more directly addressing the labrum.

Normal motion of the hip in stance, walking, and sitting is most often flexion–extension in the sagittal plane, and internal and external rotation in the transverse plane. Abduction and adduction in the coronal plane is limited, except in instances of muscle weakness. The proximal femur, moving in this sagittal plane, articulates with a joint that is neither in the sagittal nor in the coronal plane, i.e., the acetabulum is not directly in front of the femur as it flexes and extends, but is in an oblique plane. As previously described, this obliquity is normally 20° off the sagittal in the central and caudal acetabulum and 8° in the cranial part [12, 13]. That means that, as the femur flexes, coming against the acetabulum, a specific portion of the femoral neck comes in contact with the acetabulum medially and cranially, the anterior and anterior-cephalic portion of the labrum bearing the initial contact [14]. As the hip continues to flex, increasing anterior femoral neck contact occurs with different areas of the labrum along the oblique margin of the acetabular rim. With extension, femoral neck contact with the acetabulum and labrum is simultaneously posterior and medial. Thus, because of the obliquity of the acetabular plane, flexing and extending the femur causes different circumferential parts of the neck to come against the labrum as the motions progress.

This variation is even greater as internal and external rotation occur during the gait cycle, when standing, and when sitting. When the hip is abducted into the “frog” position, the lateral femoral neck comes against the posterior labrum and acetabulum. Varying the rotation with abduction further changes the area of the neck in contact. Varying degrees of femoral version change the degree of contact. These different positions in their extremes place loads and stress on different portions of the labrum. The area and degree of potential labral impingement thus vary as these positions change.

In the “normal” hip, the labrum is uninjured by all of these motions as the “normal” acetabulum and labrum articulate with the circumferential concave surface of the femoral neck. In addition, the normal femoral anteversion allows for internal rotation of the femur to occur without unusual anterior acetabular and labral contact and impingement. However, in instances of slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), coxa vara, pistol grip deformity, head tilt deformity, and growth anomalies of the epiphysis, as well as hypertrophic femoral neck changes from abnormal acetabular edge contact, the neck concavity is obliterated or distorted [15] (Fig. 9). The femoral neck may be malpositioned because of relative or absolute femoral retroversion. Additionally, these abnormalities in the femoral neck are not necessarily in the sagittal or coronal plane. Labral injury may occur because of the distortion or absence of the neck concavity malrotation. For example, in SCFE, the maximum neck deformity is a convexity and prominence, which is neither directly anterior nor directly lateral, but in an oblique plane, the antero-lateral femoral neck. In this abnormal instance, as the hip flexes, labral contact occurs earlier than normal in the motion; as flexion continues toward completion, impingement occurs. Clinically, this is apparent when a hip with SCFE is flexed. As the hip moves sagittally, the prominent antero-lateral femoral neck deformity hits the edge of the acetabulum and labrum; the prominence then rides the anterior edge of the acetabulum and labrum laterally and posteriorly, externally rotating the femur—the classic Whitman’s sign of SCFE. Three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) evaluation of the hip [16] (Fig. 10) clearly demonstrates these changes and abnormal contacts. Additionally, in SCFE, the areas of greatest labral contact changes are less medial and more antero-medial and superolateral. As the severity of the SCFE increases, more posterior acetabular and labral contact and stress occur. Injury and tears of the labrum are further understood by this reasoning and example.

Fig. 9.

Hypertrophic femoral neck changes from abnormal acetabular edge contact (modified with permission from Allen et al. [15], Fig. 3)

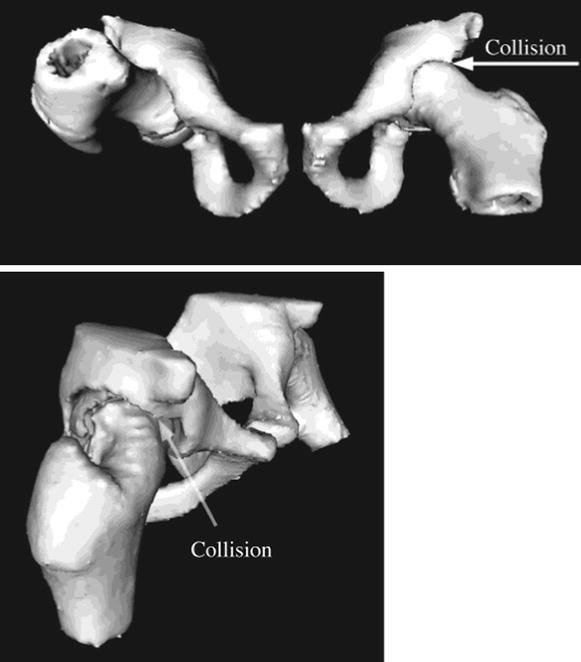

Fig. 10.

Three-dimensional representation of the abnormal labral acetabular edge contact that occurs anteriorly and at the posterior cartilage–labrum surface with slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) (modified with permission from Richolt et al. [16], Figs. 3 and 4)

Thus, in the normal articulation, the acetabulum is in an oblique plane and articulates with a sagittally directed femur. The labrum is protected by the normal femoral neck concavity and femoral anteversion, as long as normal or physiologic ranges of motion are not exceeded. However, if femoral neck changes or retroversion occurs, impingement is likely and is made worse as the deformed or malaligned femur approaches the oblique plane of the acetabulum. Situations usually not thought of as “impingement,” such as the traumatically dislocated hip, are certainly “impingement.” When caring for the dislocation, with or without bony reconstruction, injury to the labrum should be considered, evaluated, and treated appropriately.

It is clear that the location and extent of the tears of the labrum reflect the areas of higher force or the severity of the loads on the labrum. For example, because of the normal anterior orientation of the acetabulum and the anteversion of the femur, the femoral head relies for support anteriorly on the labrum to a varying degree, a potential for tear. The greater the femoral anteversion and/or acetabular anteversion and/or dysplasia, the more the femoral head relies on the labrum for support and the more likely and greater will be the tear. In instances of acetabular dysplasia, this increased tension load on the labrum results in hypertrophy of the labrum and frequent tears [17]. Similarly, although posterior tears usually occur with the trauma of extension and external rotation, prolonged and repeated sitting on the legs, as seen in the Far East, is said to be one of the reasons for a high incidence of posterior labral tears [17].

The function and stabilizing influence of the labrum

Histologic structure of the labrum

The labrum has three collagen layers, with the fibers being arranged differently in each layer. Understanding the arrangement of these fibers is critical to understanding the stabilizing nature and function of the labrum:

Layer 1—Collagen fibers have a random orientation.

Layer 2—Collagen fibers are in bundles. The bundles intersect at various angles. They are thicker in the cranial direction, and thinner in the anterior and posterior directions.

Layer 3—Collagen fibers have circular orientation. The external and internal fibers merge with fibers of the transverse acetabular ligament. This is the main layer [6].

Stabilizing benefits of the circular structure of the labrum/transverse ligament

The circular labrum, as stated, is moored to the transverse ligament and pillars of the acetabular notch. The femoral head, seated in the acetabulum, is a radially directed force against the labrum. The labrum, being attached relatively loosely to the acetabular rim, is thrust away from these attachments, coming under tension. This tension, increasing with the thrust of the femoral head, becomes so great that the labrum, unyielding to this force, actually becomes stiffer than the adjacent articular cartilage, thus, stabilizing the joint [6]. In resisting the lateral motion of the femoral head, the labrum preserves the congruity of the joint.

The labral seal, preventing consolidation, protecting the inherent normal cartilage structure

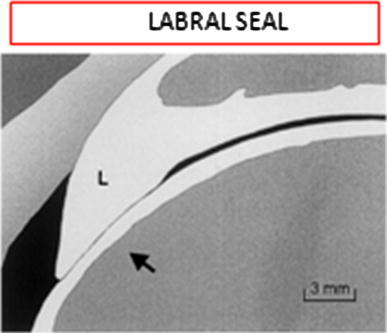

The labrum, stiff under tension, acts as a seal, sealing the joint fluid within the space between the labrum and the articular cartilage [18] (Fig. 11). This joint space contains a 0.4-mm layer of incompressible, pressurized fluid. This fluid, driven to the periphery, protects the articular cartilage by distributing and decreasing the peak loads on the articular cartilage of the femoral head, except at the thickened periphery of the labrum (black arrow) (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

The labrum, stiff under tension, acts as a seal. The joint space, thus, contains a 0.4-mm layer of pressurized fluid, which protects the articular surfaces. Contact is resisted by the high fluid pressures and the tight labral ring (black arrow), where the peak strain can reach 2 %. This pressurizes the interstitial fluid within the cartilage. This pressurization resists “consolidation” or the forcing of fluid out of the cartilage (reproduced with permission from Ferguson et al. [18], Fig. 1)

The force of the pressurized fluid is transmitted to the interstitial fluid within the articular cartilage. Without this pressurization of the fluid within the cartilage, internal and external loads would drive the interstitial fluid out of the cartilage, resulting in compression of the solid elements of the articular cartilage, a process called consolidation. This would result in an altered state of the cartilage, vulnerable to degeneration and arthritis. This seal prevents consolidation.

Thus, under normal functioning of this system, the seal creates a 0.4-mm space of joint fluid between the femoral head and the acetabulum–labrum complex, protecting the articular cartilage. In effect, we are “walking on water” (joint fluid).

Actual contact of the two surfaces (with the risk of consolidation) normally only occurs at high external loads. In the abnormal situation of labral excision, as stated by Ferguson et al., there is 92 % higher solid-on-solid contact stress and higher subsurface strain [18, 19] (Fig. 11). Consolidation occurs.

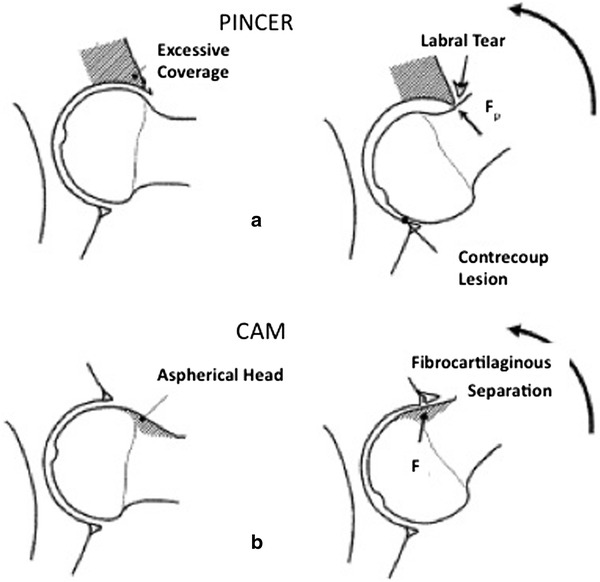

Labral tears

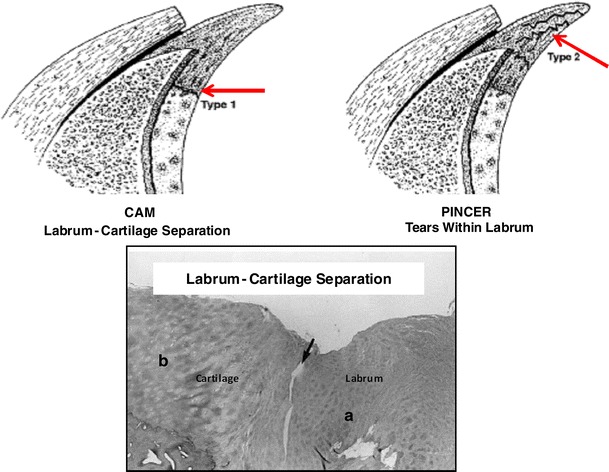

The labrum tears differently depending on whether the primary cause of the FAI is cam or pincer [20] (Fig. 12). In the instance of cam, there is a separation between the labrum and the articular hyaline cartilage, a cleavage plane occurring, often associated with articular cartilage delamination. With pincer, tears occur within the substance of the labrum itself [5] (Fig. 13). Examples of tears associated with pincer and cam are seen in the photographs by Ganz et al. [21] (Fig. 14).

Fig. 12.

Types of tears of the labrum. a Pincer type femoro-acetabular impingement—tears within the labrum. b Cam type impingement—cleavage separation between the labrum and articular cartilage (modified with permission from Tannast and Siebenrock [20], Fig. 2)

Fig. 13.

Tears of the labrum with cam and pincer impingement (modified with permission from Seldes et al. [5], Figs. 5 and 6)

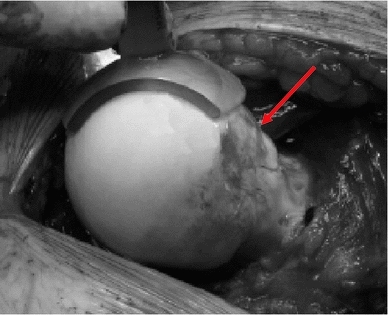

Fig. 14.

a Labral tears from pincer femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI). b Labrum articular cartilage cleavage with delamination of articular cartilage from cam FAI (modified with permission from Ganz et al. [21], Fig. 5a, b)

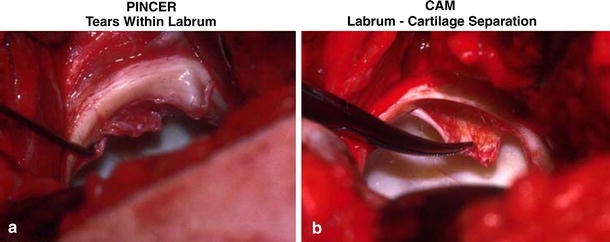

The types of tears have been classified based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), direct intra-articular injection magnetic resonance arthrography (d-MRA), arthroscopic examination, and indirect intravenous magnetic resonance arthrography (i-MRA).

Czerny et al. [22] described the d-MRA characteristics (Fig. 15). They distinguished (I) a labrum with no surface tears, (II) a labrum with surface tears, and (III) labrum articular cartilage separation. They also distinguished between abnormal labrum (A) without intrasubstance cyst-like signals and (B) those with. Thus, they described labrum with no surface tears (IA no cyst and IB cyst), labrum with articular surface tears (IIA no cyst and IIB cyst), and separation cleavage tear between the labrum and hyaline articular surface (IIIA no cyst and IIIB cyst).

Fig. 15.

(I) No surface labral damage, (II) labral surface damage, (III) labral articular cartilage separation, (A) no intrasubstance labral cysts, (B) intrasubstance labral cysts (modified with permission from Czerny et al. [22], Fig. 2)

Lage et al. [23] arthroscopically observed tears caused by various etiologies: degenerated (48.6 %), idiopathic (27.1 %), traumatic (18.9 %), and congenital (5.4 %). Morphologically, there were radial flaps (56.6 %), longitudinal peripheral tears (26 %), radial fibrillated tears (21.6 %), and unstable tears (5.4 %). These morphologic changes did not correlate as well with the Czerny MRA classification.

Structural osseous abnormalities noted on conventional X-ray in patients with established labral tears were studied in a series of cases at the Mayo Clinic in 2004. Excluding acetabular dysplasia and advanced osteoarthritis, there were structural osseous changes of the femur in 27 of 31 cases, over 35 % with multiple findings. This included ten cases of recognizable retroversion, 16 instances of coxa valga, 11 cases of abnormal femoral head–neck offset, and 14 instances of osteophytes noted at the femoral head–neck margin [24]. As a corollary, when impingement symptoms occur in patients with these conditions, it must be remembered that labral tears may exist. When treating the described structural osseous conditions, labral tears need to be addressed. These osseous causes for impingement must be treated prior to treating or re-establishing labral continuity.

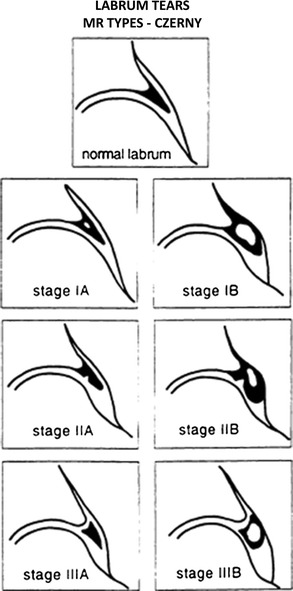

Ilizaliturri et al. [14] divided the face of the acetabulum into six zones (Fig. 16). Most instances of anterior impingement that cause labral tears occur mainly in zone 1, but also in zones 2 and 3. Posterior tears are seen in zones 4 and 5. These tears can be seen in lateral and radial MRA views of the femoro-acetabular articulation [25] (Fig. 17).

Fig. 16.

Most anterior impingement that causes labral tears occurs mainly in zone 1, but also in zones 2 and 3. Posterior tears are seen in zones 4 and 5 (modified with permission from Ilizaliturri et al. [14], Fig. 3)

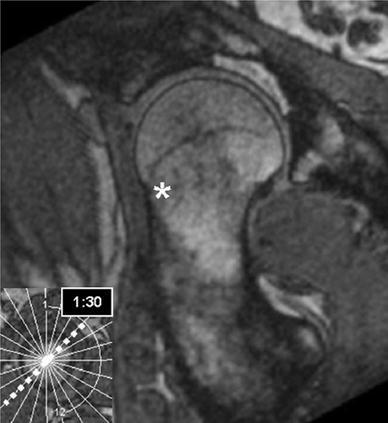

Fig. 17.

Lateral and radial Images of femoral head–neck offset. The asterisk shows the area of acetabulum/labrum abnormal zone (white area) (reproduced with permission from Hack et al. [25], Fig. 3C)

Where is the pain from?

The labrum has sensation! There are many different types of sensory nerve end organs, as well as free sensory nerve endings. Free endings transmit pain, tactile sensation, and temperature. Sensory end organs include Vater-Pacini (pressure), Golgi-Mazzoni (pressure), Ruffini (deep sensation, temperature), and articular (Krause) corpuscles (pressure, pain). These structures are mostly in layer one (outer layer) of the labrum [26].

The implication of the existence of these various sensory structures is that symptoms and findings of impingement can have their origin in the labrum, as well as the associated osseous structures. Early impingement from repeated structural compression of the labrum, but without permanent injury, may create symptoms; associated physical findings may be elicited if sought, i.e., possibly prior to irreversible damage. Attention at this stage may theoretically be able to prevent permanent labral damage.

How is the diagnosis of labral tear from cam impingement made?

When a patient is having hip pain, and when hip impingement is being considered, the concern for possible tear(s) of the labrum requires an appropriate diagnostic protocol. Our recent article on FAI dealt extensively with the diagnosis of FAI and, in particular, emphasized acetabular causes and will not be repeated [1]. The reader is referenced to that article and is also directed to the article by Burnett et al. [27], dealing with the history and clinical tests for FAI and labral tears.

Having established acetabular causes and regimen of diagnosis, the possibility of cam impingement should be considered as a cause of the pain and its existence established. Cam impingement conditions all have in common reduced head–neck offset and/or reduced femoral version.

The pistol grip deformity, horizontal growth plate, and a CCD (caput–collum–diaphyseal, i.e., head–neck–shaft) angle less than 125° are signs on the anteroposterior (AP) X-ray view. Lateral X-ray measurements of the femoral head neck taken in neutral rotation include head–neck offset, alpha angle, and beta angle [20].

An 8-mm head–neck offset is used as the normal standard when measuring cam. Less than 8 mm is considered indicative of cam [20] (Fig. 18). The alpha angle measures the sphericity of the femoral head and, by inference, the degree of offset between the femoral head and neck. The beta angle measures the degree at which the offset impinges on the acetabulum, essentially, the faux profile view.

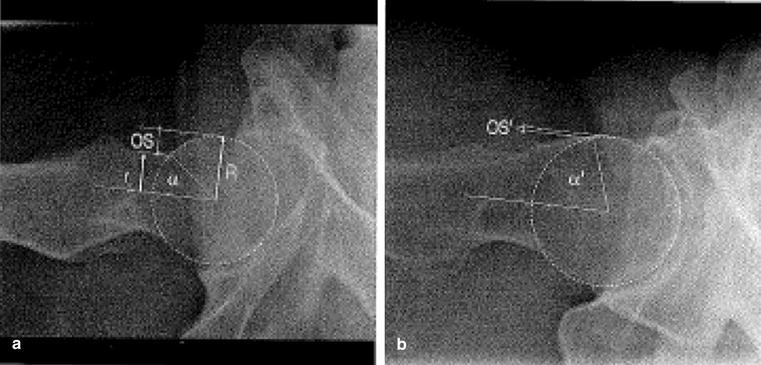

Fig. 18.

a Normal head–neck offset (OS). b Abnormal head–neck offset (OS’) due to hypertrophic femoral neck changes (reproduced with permission from Tannast and Siebenrock: [20], Fig. 14)

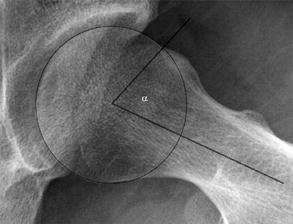

The alpha angle is measured by placing a circle around the femoral head. A line is drawn along the center of the femoral neck to the center of the head. The angle is created by drawing a second line from where the first line meets the center of the femoral head to the point where the bony edge of the femoral head–neck junction meets the anterior margin of the circle. The more the hypertrophic neck changes or the greater the head–neck offset, the smaller the angle. The angle obviously can be measured on any good view of the femoral head neck area, i.e., standard X-rays, CT, MRI, etc. However, in the initial instance of examining the symptomatic hip, standard AP films measured in neutral rotation in extension or flexion, the Dunn view, are usually obtained. Studies vary as to what is the average alpha angle in symptomatic hips, the range varying up to 74° [28]. In another study, the normal alpha angle for men was 68° or less and for women it was 50° or less [15] (Fig. 19). However, it is generally accepted that alpha angles of 50° or less are considered to be normal for both genders in the specific plane in which it is measured.

Fig. 19.

Normal alpha angle among men was 68° or less and in women, it was 50° or less (reproduced with permission from Allen et al. [15], Fig. 1)

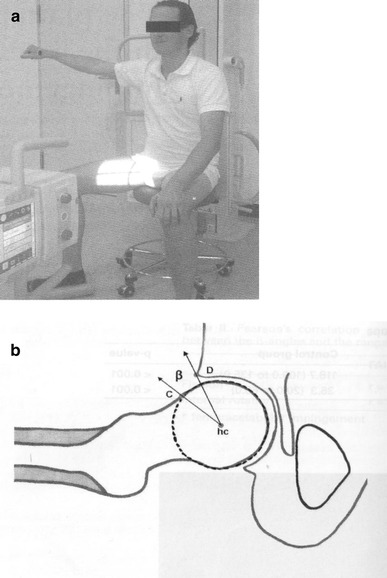

The beta angle (Fig. 20) is the angular distance in degrees from the edge of the acetabulum to the point just before a concentric femoral head circle is disrupted by the offset. This should be done at 90° of flexion with the X-ray tube medially rotated 15–20° to address the face of the acetabulum; normal is 30°–57° and FAI is present at 15° (range 1°–29°) [29].

Fig. 20.

a Method of taking X-rays to measure the beta angle. b The beta angle defines limits for normal (average 38.7°) and FAI (average 15.6°) (modified with permission from Brunner et al. [29]: p. 1204, Fig. 1; p. 1205, Fig. 2)

Retroversion of the femoral neck, suspected clinically, is best measured by CT version studies. The angular pitch of the femoral neck (angle made between the line of the neck and the horizontal) is measured against the femoral condyle angle (the angle made between a line connecting the back of the condyles and the horizontal) [22].

The problem with using the alpha and beta angles to diagnose cam is that these studies, as stated, are usually taken in the neutral AP and lateral position. They, thus, depend on the neck pathology being in that plane, either partially or in total. This is by no means consistently the case. Other diagnostic tests are, therefore, required to ensure “out-of-plane” abnormalities are recognized. Frog-leg lateral views were stated to better visualize these abnormalities by Clohisy et al. [30].

CT and 3D CT are frequently used once the clinical signs of FAI are present, to establish the acetabular and femoral causes and are capable of recognizing these “out-of-plane” abnormalities. However, they do not reveal the condition of the labrum.

MRI has been used extensively to examine the labrum. Sequentially, it is able to recognize the osseous deformities, but not as well or understandably as 3D CT. It recognizes abnormalities of the labrum by changes in the character of the T1 and T2 representation of the labrum. However, it does not clearly visualize the internal condition of the labrum. Standard MRI produces both false-positive and false-negative results and is only 30 % sensitive and 36 % accurate [22]. One of the false-positive problems has been interpreting the labral sulcus as a tear. However, recently reported improvements in MRI techniques have brought the sensitivity and accuracy close to the values found with MRA [31]. The increasing availability of these recent techniques will make MRI more valuable.

MRA has significantly improved viewing the condition of the labrum. It is done with either intravenous i-MRA or intra-articular d-MRA infusion of gadolinium. If instilled directly into the joint, distention occurs and significantly improves the study. Czerny et al. [22] showed that, with distention, the sensitivity was 90 % and the accuracy was 91 %. Without distention, the sensitivity and accuracy were only 30 and 36 %, respectively. However, once again, we see recent technical improvements. They have significantly improved the quality and results from i-MRA, which are now approaching the sensitivity and accuracy of d-MRA. In addition, i-MRA has the advantage of examining the vascular supply to the cartilage, labrum, and subchondral bone [32]. Thus, i-MRA is capable of revealing other intra- and extra-articular pathology, as well as labral abnormalities.

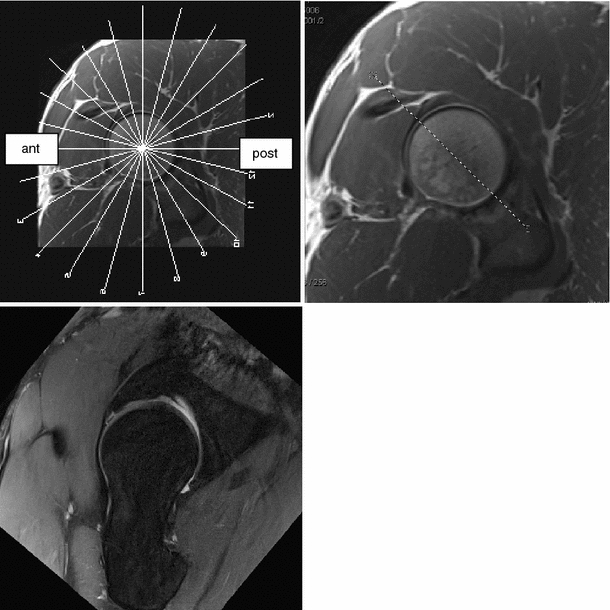

These studies, AP, lateral, and oblique, can identify the extent and nature of the tears in the areas which each examines. However, the use of radial images taken in the plane of the acetabulum exhibit the face of the labrum in a clock-like manner, showing the front-to-back extent of the tears of the labrum, as well as showing the direction within the radius [32] (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21.

Indirect magnetic resonance arthrography of the hip at 3T with radial images. Top left: en face image of the acetabular opening with overlaid radial sections. Top right: plane of section for the bottom left image. Bottom left: fat suppressed, proton density radial image showing tear of the anterosuperior labrum (modified with permission from Petchprapa [32])

The use of MRA has shown the added value of the Lage classification, which is able to define the intrasubstance nature of the tears, whereas Czerny’s classification described the labral morphology, intralabral signal, and the presence of a tear or labral detachment. The two systems did not correlate well, as the Czerny system was more at the gross specimen level, whereas the Lage system looked further into the labrum [33].

With improving technology and experience, there has been an increasing use of arthroscopy for both diagnostic as well as the treatment of hip pain associated with FAI, diagnosing as well as treating both osseous and labral pathology. The pediatric, adult, and arthroscopy literature are replete with such reports, all confirming the labrum as the victim of FAI [34, 35].

Preservation of labral function

The two main functions of the labrum, enhancing hip stability and protecting the articular cartilage (the labral seal), are best preserved. Studies have shown that excision of the labrum frequently results in a symptomatic hip with a greater frequency of resultant arthritis than when the labrum is preserved or repaired [36, 37].

There are two prevailing surgical methods of preserving the labrum after surgically addressing the causes of the impingement and the labral pathology. In both methods, suture anchors are placed in the bony rim. One method then lassoes the labrum. The other method sutures the labrum at its base to the rim [36, 37]. Both methods enhance hip stability and result in less symptomatic hips. However, only the second method attempts to create a smooth periphery. Theoretically, that is more likely to recreate the seal, further protecting the hip by preventing consolidation.

In summary, preservation of the hip requires knowledge of the factors endangering this goal. When FAI is being considered as threatening this integrity, understanding how to treat and preserve the structure initially injured, the labrum, as well as the various osseous causes of FAI, is important. It is furthered by a more complete knowledge of the labrum, namely, its anatomy, circulation, histology, embryology, and neurology, as well as how the labrum tears and the types of tears. How the labrum tears is made complex by the oblique plane direction of the acetabulum and variations of the femoral head–neck offset. Continuous improvement in MRI has made diagnosis reliable, with a high sensitivity and accuracy to these studies (92 and 90 %, respectively).

The purpose of this article was to collect the varied essential information about the labrum in one succinct review, independent of the treatment algorithms. It is intended that this knowledge further the awareness of how the labrum enhances stability and protects the articular surface, and, thus, defines the principles that should guide the treatment of the labrum and preservation of these functions. Reports of the varied approaches to treatment and the effect of these treatments are continuously occurring as progressively longer term results are observed, i.e., [38–40]. The reader needs this basic information on the labrum to properly evaluate these reports.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors received financial support for this study.

References

- 1.Grant AD, Sala DA, Schwarzkopf R. Femoro-acetabular impingement: the diagnosis—a review. J Child Orthop. 2012;6:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11832-012-0386-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaulé PE, O’Neill M, Rakhra K. Acetabular labral tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:701–710. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant JCB. An atlas of anatomy. 3. London: Bailliere, Tindall and Cox; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray H (1948) Anatomy of the human body, 25th edn. Edited by Charles Mayo Goss). Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia

- 5.Seldes RM, Tan V, Hunt J, Katz M, Winiarsky R, Fitzgerald RH., Jr Anatomy, histologic features, and vascularity of the adult acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;382:232–240. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen W, Petersen F, Tillmann B. Structure and vascularization of the acetabular labrum with regard to the pathogenesis and healing of labral lesions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123:283–288. doi: 10.1007/s00402-003-0527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cashin M, Uhthoff H, O’Neill M, Beaulé PE. Embryology of the acetabular labral-chondral complex. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1019–1024. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B8.20161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung SM. The arterial supply of the developing proximal end of the human femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:961–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalhor M, Beck M, Huff TW, Ganz R. Capsular and pericapsular contributions to acetabular and femoral head perfusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:409–418. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grose AW, Gardner MJ, Sussmann PS, Helfet DL, Lorich DG. The surgical anatomy of the blood supply to the femoral head: description of the anastomosis between the medial femoral circumflex and inferior gluteal arteries at the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1298–1303. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B10.20983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly BT, Shapiro GS, Digiovanni CW, Buly RL, Potter HG, Hannafin JA. Vascularity of the hip labrum: a cadaveric investigation. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds D, Lucas J, Klaue K. Retroversion of the acetabulum. A cause of hip pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:281–288. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B2.8291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamali AA, Mladenov K, Meyer DC, Martinez A, Beck M, Ganz R, Leunig M. Anteroposterior pelvic radiographs to assess acetabular retroversion: high validity of the “cross-over-sign”. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:758–765. doi: 10.1002/jor.20380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilizaliturri VM, Jr, Byrd JW, Sampson TG, Guanche CA, Philippon MJ, Kelly BT, Dienst M, Mardones R, Shonnard P, Larson CM. A geographic zone method to describe intra-articular pathology in hip arthroscopy: cadaveric study and preliminary report. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen D, Beaulé PE, Ramadan O, Doucette S. Prevalence of associated deformities and hip pain in patients with cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:589–594. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B5.22028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richolt JA, Teschner M, Everett PC, Millis MB, Kikinis R. Impingement simulation of the hip in SCFE using 3D models. Comput Aided Surg. 1999;4:144–151. doi: 10.3109/10929089909148169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groh MM, Herrera J. A comprehensive review of hip labral tears. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2009;2:105–117. doi: 10.1007/s12178-009-9052-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson SJ, Bryant JT, Ganz R, Ito K. The acetabular labrum seal: a poroelastic finite element model. Clin Biomech. 2000;15:463–468. doi: 10.1016/S0268-0033(99)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terayama K, Takei T, Nakada K. Joint space of the human knee and hip joint under a static load. Eng Med. 1980;9:67–74. doi: 10.1243/EMED_JOUR_1980_009_017_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tannast M, Siebenrock KA. Conventional radiographs to assess femoroacetabular impingement. Instr Course Lect. 2009;58:203–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, Harris WH. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip: an integrated mechanical concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:264–272. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0060-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Czerny C, Hofmann S, Neuhold A, Tschauner C, Engel A, Recht MP, Kramer J. Lesions of the acetabular labrum: accuracy of MR imaging and MR arthrography in detection and staging. Radiology. 1996;200:225–230. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.1.8657916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lage LA, Patel JV, Villar RN. The acetabular labral tear: an arthroscopic classification. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:269–272. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(96)90057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wenger DE, Kendell KR, Miner MR, Trousdale RT. Acetabular labral tears rarely occur in the absence of bony abnormalities. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;426:145–150. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000136903.01368.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hack K, Di Primio G, Rakhra K, Beaulé PE. Prevalence of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement morphology in asymptomatic volunteers. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2436–2444. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim YT, Azuma H. The nerve endings of the acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;320:176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burnett RS, Della Rocca GJ, Prather H, Curry M, Maloney WJ, Clohisy JC. Clinical presentation of patients with tears of the acetabular labrum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1448–1457. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nötzli HP, Wyss TF, Stoecklin CH, Schmid MR, Treiber K, Hodler J. The contour of the femoral head-neck junction as a predictor for the risk of anterior impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:556–560. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B4.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunner A, Hamers AT, Fitze M, Herzog RF. The plain β-angle measured on radiographs in the assessment of femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:1203–1208. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B9.24410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clohisy JC, Nunley RM, Otto RJ, Schoenecker PL. The frog-leg lateral radiograph accurately visualized hip cam impingement abnormalities. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;462:115–121. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180f60b53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mintz DN, Hooper T, Connell D, Buly R, Padgett DE, Potter HG. Magnetic resonance imaging of the hip: detection of labral and chondral abnormalities using noncontrast imaging. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petchprapa C (2012) Personal communication

- 33.Blankenbaker DG, De Smet AA, Keene JS, Fine JP. Classification and localization of acetabular labral tears. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36:391–397. doi: 10.1007/s00256-006-0240-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jayakumar P, Ramachandran M, Youm T, Achan P. Arthroscopy of the hip for paediatric and adolescent disorders: current concepts. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:290–296. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B3.26957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roy DR. Arthroscopy of the hip in children and adolescents. J Child Orthop. 2009;3:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s11832-008-0143-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang WG, Yue DB, Zhang NF, Hong W, Li ZR. Clinical diagnosis and arthroscopic treatment of acetabular labral tears. Orthop Surg. 2011;3:28–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1757-7861.2010.00121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farjo LA, Glick JM, Sampson TG. Hip arthroscopy for acetabular labral tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:132–137. doi: 10.1053/ar.1999.v15.015013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Philippon MJ, Arnoczky SP, Torrie A. Arthroscopic repair of the acetabular labrum: a histologic assessment of healing in an ovine model. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:376–380. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larson CM, Giveans MR. Arthroscopic debridement versus refixation of the acetabular labrum associated with femoroacetabular impingement. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larson CM, Giveans MR, Stone RM. Arthroscopic debridement versus refixation of the acetabular labrum associated with femoroacetabular impingement: mean 3.5-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:1015–1021. doi: 10.1177/0363546511434578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]