Abstract

Ultrasound-guided cannulation of a large-bore catheter into the internal jugular vein was performed to provide temporary hemodialysis vascular access for uremia in a 65-yr-old woman with acute renal failure and sepsis superimposed on chronic renal failure. Despite the absence of any clinical evidence such as bleeding or hematoma during the procedure, a chest x-ray and computed tomographic angiogram of the neck showed that the catheter had inadvertently been inserted into the subclavian artery. Without immediately removing the catheter and applying manual external compression, the arterial misplacement of the hemodialysis catheter was successfully managed by open surgical repair. The present case suggests that attention needs to be paid to preventing iatrogenic arterial cannulation during central vein catheterization with a large-bore catheter and to the management of its potentially devastating complications, since central vein catheterization is frequently performed by nephrologists as a common clinical procedure to provide temporary hemodialysis vascular access.

Keywords: Hemodialysis, Complication, Central Venous Catheterization

INTRODUCTION

Central vein cannulation (CVC) using a large-bore catheter (≥ 7.0 Fr) is widely used in renal patients for hemodynamic monitoring, rapid large-volume replacement, parenteral nutrition or antibiotic administration, and hemodialysis (HD). In particular, the creation of temporary vascular access by CVC for HD under ultrasound (US) guidance, preferably using the internal jugular vein (IJV), is increasingly accepted as a straightforward procedure by nephrologists and the so-called "the new nephrologist" trained in nephrology-related procedures. The aim is to minimize procedure-related delays in initiating immediate HD therapy, improve the convenience of those patients, and enhance the doctor-patient relationship (1). However, although this procedure has helped numerous renal patients with uremia, it occasionally has serious complications, and can even lead to fatal outcomes. Therefore, through described our case, nephrologists and nephrology-trainees should not only be thoroughly trained in the temporal HD catheter (THC) placement, but should also be well-informed about how to prevent and manage the procedure-related complications such as arterial injury and arterial misplacement.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 65-yr-old woman with an underlying chronic kidney disease was presented to the emergency room (ER) with uremia because of sepsis accompanied by oliguria and severe metabolic acidosis on August 29, 2008. To begin emergency HD, we attempted to insert a 7.5 French (Fr) catheter into the right IJV under ultrasound guidance. The initial puncture with an 18-gauge needle into the right IJV using real-time US guidance by the short-axis method was successful with no pulsatile arterial back flow. Thereafter, the rest of the procedure with removal of the ultrasound transducer was performed without any resistance to advancing the guide wire and HD catheter by the Seldinger technique. No immediate complications such as rapidly expanding hematoma, pain, dyspnea, shock, or signs of neurologic deficits were noticed during insertion of the THC. However, a routine post-cannulation chest X-ray suggested that the catheter tip had been misplaced into the right subclavian artery (SCA) (Fig. 1), and subsequent computed tomographic (CT) angiography with contrast enhancement revealed that the catheter had indeed passed through the right IJV and been misplaced into the right SCA (Fig. 2). We assumed that the puncture needle had initially been inserted into the right IJV, but had been unintentionally advanced into the right SCA after the absence of arterial back flow had been established and before inserting the guide wire.

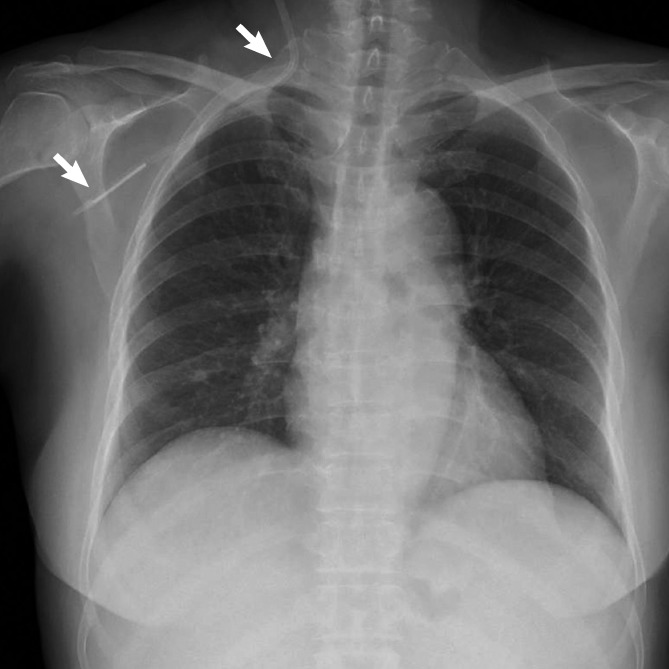

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray following central vein cannulation for a temporary hemodialysis vascular access via the right internal jugular vein showing that the catheter might have been misplaced in the right subclavian artery (arrows).

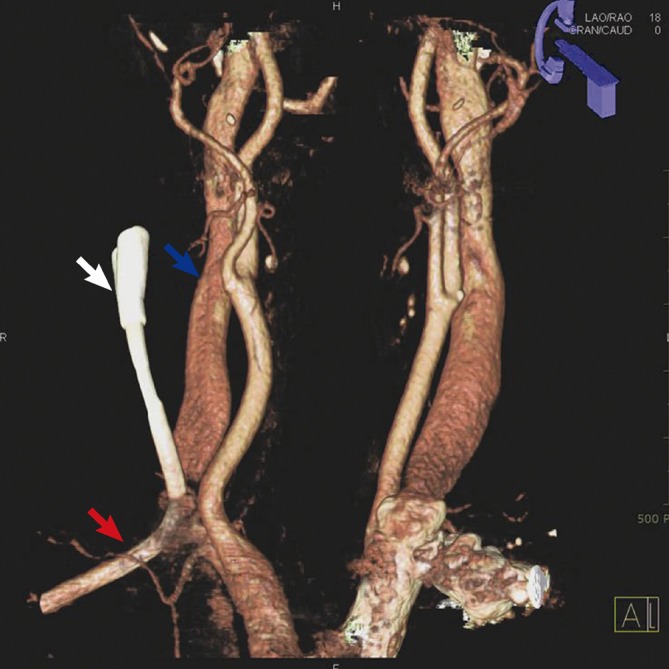

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of computed tomographic angiography of the neck through the inadvertently inserted catheter confirming that it (white arrow) had penetrated the vessel wall of the right internal jugular vein (blue arrow) and had been inserted into the right subclavian artery (red arrow).

The HD catheter into the right SCA was left in place without an immediate catheter removal and direct external compression, because of the uncontrollable arterial bleeding that might result from application of the pull/pressure technique. Following consultation with a vascular surgeon, the surgical exploration in the operating room revealed that the HD catheter had transected the right IJV and the right SCA. The catheter was removed and the SCA injury was surgically repaired without complications. An angiogram under real-time fluoroscopy revealed no further bleeding or fistula between right IJV and right SCA (Fig. 3). Also, subsequent evaluation of neurological status following open surgical repair and angiography for any intra-arterial catheter-related thrombi or emboli, revealed no neurologic deficit. The patient underwent an uneventful hospital course with antibiotic therapy and intermittent hemodialysis through the THC into the right femoral vein, as required. HD was stopped on the 12th hospital day.

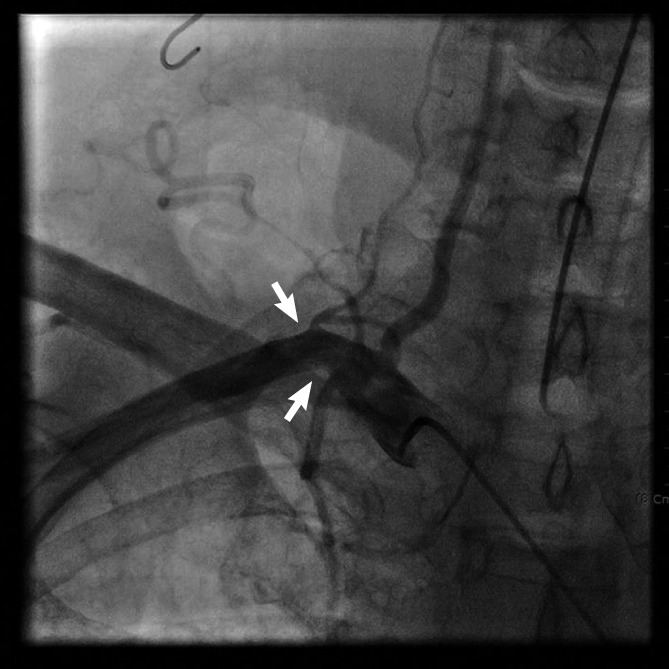

Fig. 3.

Angiogram following open surgical repair showing absence of visible bleeding and of any arterio-venous fistula of the right subclavian artery (arrows).

DISCUSSION

Among the various mechanical complications of CVC, unintended arterial cannulation has been reported to occur in up to 8% of the cases (2), and has been particularly noted in patients at high risks due to obesity, short neck, emergency puncture and hemodynamic instability with severe hypotension or low hemoglobin saturation or coagulation defects, as well as in the absence of ultrasound guidance (3). Iatrogenic arterial injury to patients following percutaneous CVC with a large-bore catheter (≥ 7.0 Fr) has resulted in various devastating complications such as arteriovenous fistula, arterial dissection, pseudoaneurysm, airway obstruction with massive cervical bleeding and hematoma, shock from hemothorax, stroke from arterial thrombosis or cerebral emboli, and even fatality (4).

Compared to traditional blind central venous catheter placement using superficial anatomical landmarks, catheter placement under US guidance achieved an initial high success rates including fewer needle attempts, rapid vein localization and fewer complications (3, 5, 6). In fact, the use of US-guided CVC lowered the risk of complications by up to 73% (7). However, inadvertent arterial trauma or cannulation under US-guided CVC, as in our case, still occurs (7). There is evidence that novice operators of ultrasonograms may lose track of the puncturing needle tip when using the short-axis method only, rather than both short- and long-axis trials, and this can lead to the accidental arterial cannulation (8). As in our case, accidental advancing of the puncture needle into an artery prior to insertion of the guide wire, with no further tracing under US guidance after confirmation of absence of pulsatile blood return or puncture of the right IJV, has been reported (9). Thus, the CVC of a large-bore catheter under US guidance is not always guaranteed as a safe procedure free from the risk of inadvertent arterial cannulation.

Once inadvertent arterial cannulation of a large-bore catheter is suspected, immediate management of arterial injury following its confirmation by imaging studies is required to avoid complications from prolonged arterial cannulation such as thrombus at the site of arterial injury. Compared to surgical specialties (3, 4), workers in the nephrology field have seldom proposed definite guidelines on how to manage this accidental arterial cannulation (10, 11). Scattered case reports have documented accidental arterial catheterization of CVC, but they barely mentioned methods of managing these complications and how to predict the likely success of the chosen option, i.e., pull/pressure with immediate catheter removal and manual external compression, open surgical exploration with catheter removal, or arterial repair under direct vision, and endovascular interventions.

The pull/pressure technique has been well recognized for resulting in serious complications such as massive hemorrhage leading to respiratory distress, pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula, and strokes (12-14). Also, cases of bleeding after pull/pressure technique require urgent open surgical intervention. The probability of serious complications is usually dependent on catheter diameter, time since catheter insertion and puncture site (3). A retrospective analysis of 30 cases of arterial misplacement with large-bore cannula (≥ 7.0 Fr) showed that, unlike the pull/pressure technique, managements by immediate surgical exploration and artery repair under direct vision caused no complication at all and was considered the most effective and safe treatment (46% vs 0%, P = 0.004) (4). Furthermore, a retrospective analysis of 57 cases based on published series and case reports of carotid artery or SCA catheterizations with large-bore cannula revealed that the pull/pressure technique was associated with significantly more complications than surgical or endovascular repair (relative risk, 17.86; P < 0.001) (4). In the same study, a single patient in the surgical repair group (1/14) developed a post-surgery embolic stroke due to delayed surgical intervention after cannulation of the carotid artery for more than 72 hr (15). Thus, prompt open surgical repair has been noticed to be safe, but its usual requirement for general anesthesia and even sternotomy cause some morbidity in patients with serious underlying diseases including uremia (3). Recently, less invasive endovascular interventions, such as use of a covered stent or percutaneous arterial closure device or balloon tamponade, have been reported (16-18). These options are ideal for managing arterial injuries that are difficult to expose or inaccessible surgically, such as in the proximal carotid or subclavian artery below or behind the clavicle (4). Although one recent retrospective analysis for the endovascular interventions of 13 patients of inadvertent SCA catheterization was promising with clinical success rate of 100% and without need for surgical reconstruction, complications requiring additional stent-graft placement were still noticed in 4 patients (30.8%) (19). Therefore, any suspected arterial catheterization during CVC should be confirmed by radiologic methods, and the catheter should be left in place without use of the pull/pressure technique while arranging for open surgical repair or the endovascular intervention with skilled experience, particularly if the location appears surgically inaccessible (3, 4).

Since the avoidance of accidental arterial cannulation is clearly preferable to its managements in CVC with a large bore catheter, the following elements are needed: 1) a properly organized instruction program for CVC under US guidance; 2) supervision of novice physicians by an experienced or interventional expert in CVC; and 3) US-guided cannulation with real-time fluoroscopy in patients at high risk. An observational cohort study comparing traditionally-trained residents for CVC versus simulation-trained residents showed that the simulation-based mastery program reduced complications related to CVC in actual patient care (20).

In summary, to prevent and manage unintended arterial cannulation during large-bore HD catheter placement, 1) cannulation should be performed by well trained and competent physicians under US guidance as a standard of care, and with real-time fluoroscopy, for high-risk patients; 2) an operator should check for excessive or pulsatile backflow through the initial puncturing needle and the cannulated catheter, as well as any expanding local hematoma, dyspnea or pain; 3) chest X-ray should be performed to check the position of the catheter tip after cannulation; 4) in the event of accidental arterial misplacement, CT angiography or conventional angiography should be immediately arranged to establish which artery is injured and to analyze the regional vascular anatomy; 5) open surgical repair or endovascular intervention, if surgery is unsuitable or experienced ones for it are available, should be promptly arranged; and 6) after surgical repair or endovascular intervention, prompt clinical evaluation should be performed to detect procedures-related neurologic deficits such as strokes.

References

- 1.O'neill WC. The new nephrologist. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:978–979. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70275-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wisborg T, Flaatten H, Koller ME. Percutaneous placement of permanent central venous catheters: experience with 200 catheters. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1991;35:49–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1991.tb03239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pikwer A, Acosta S, Kölbel T, Malina M, Sonesson B, Akeson J. Management of inadvertent arterial catheterisation associated with central venous access procedures. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guilbert MC, Elkouri S, Bracco D, Corriveau MM, Beaudoin N, Dubois MJ, Bruneau L, Blair JF. Arterial trauma during central venous catheter insertion: Case series, review and proposed algorithm. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:918–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung J, Duffy M, Finckh A. Real-time ultrasonographically-guided internal jugular vein catheterization in the emergency department increases success rates and reduces complications: a randomized, prospective study. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:540–547. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randolph AG, Cook DJ, Gonzales CA, Pribble CG. Ultrasound guidance for placement of central venous catheters: a meta-analysis of the literature. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:2053–2058. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199612000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yonei A, Nonoue T, Sari A. Real-time ultrasonic guidance for percutaneous puncture of the internal jugular vein. Anesthesiology. 1986;64:830–831. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198606000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaivas M. Video analysis of arterial cannulation with dynamic ultrasound guidance for central venous access. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:1239–1244. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.9.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone MB, Hern HG. Inadvertent carotid artery cannulation during ultrasound guided central venous catheterization. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:720. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.el-Shahawy MA, Khilnani H. Carotid-jugular arteriovenous fistula: a complication of temporary hemodialysis catheter. Am J Nephrol. 1995;15:332–336. doi: 10.1159/000168859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel HV, Sainaresh VV, Jaqin SH, Kute VB, Godara S, Gumber MR, Munjappa B, Gera DN, Shah PR, Trivedi HL. Cartotid-jugular venous fistula: a case report of an iatrogenic complication following internal jugular vein catherization for hemodialysis access. Hemodial Int. 2011;15:404–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2011.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McEnany MT, Austen WG. Life-threatening hemorrhage from inadvertent cervical arteriotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1977;24:233–236. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)63748-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah PM, Babu SC, Goyal A, Mateo RB, Madden RE. Arterial misplacement of large-caliber cannulas during jugular vein catheterization: case for surgical management. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson T, Ettles D, Robinson G. Managing inadvertent arterial catheterization during central venous access procedures. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:21–25. doi: 10.1007/s00270-003-0043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown CQ. Inadvertent prolonged cannulation of the carotid artery. Anesth Analg. 1982;61:150–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basile A, Calcara G, Rapisarda F, Fatuzzo P, Desiderio C, Granata A, Patti MT. Aberrant right subclavian artery laceration due to internal jugular vein catheterization treated by stent-graft implantation. J Vasc Access. 2010;11:80–82. doi: 10.1177/112972981001100121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu H, Stavas JM, Dixon RG, Burke CT, Mauro MA. Temporary balloon tamponade for managing subclavian arterial injury by inadvertent central venous catheter placement. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:654–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma M, Sakhuja R, Teitel D, Boyle A. Percutaneous arterial closure for inadvertent cannulation of the subclavian artery--a call for caution. J Invasive Cardiol. 2008;20:E229–E232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chemelli AP, Wiedermann F, Klocker J, Falkensammer J, Strasak A, Czermak BV, Waldenberger P, Chemelli-Steinguber IE. Endovascular management of inadvertent subclavian artery catheterization during subclavian vein cannulation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:470–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.12.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, O'Leary KJ, Wayne DB. Simulation-based mastery learning reduces complications during central venous catheter insertion in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2697–2701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]