Abstract

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal (GI) disorder that considerably reduces the quality of life. It further represents an economic burden on society due to the high consumption of healthcare resources and the non-productivity of IBS patients. The diagnosis of IBS is based on symptom assessment and the Rome III criteria. A combination of the Rome III criteria, a physical examination, blood tests, gastroscopy and colonoscopy with biopsies is believed to be necessary for diagnosis. Duodenal chromogranin A cell density is a promising biomarker for the diagnosis of IBS. The pathogenesis of IBS seems to be multifactorial, with the following factors playing a central role in the pathogenesis of IBS: heritability and genetics, dietary/intestinal microbiota, low-grade inflammation, and disturbances in the neuroendocrine system (NES) of the gut. One hypothesis proposes that the cause of IBS is an altered NES, which would cause abnormal GI motility, secretions and sensation. All of these abnormalities are characteristic of IBS. Alterations in the NES could be the result of one or more of the following: genetic factors, dietary intake, intestinal flora, or low-grade inflammation. Post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease-associated IBS (IBD-IBS) represent a considerable subset of IBS cases. Patients with PI- and IBD-IBS exhibit low-grade mucosal inflammation, as well as abnormalities in the NES of the gut.

Keywords: Cholecystokinin, Chromogranin A, Diagnosis, Diet, Endocrine cells, Intestinal flora, Hereditary, Low-grade inflammation, Peptide YY, Serotonin

INTRODUCTION

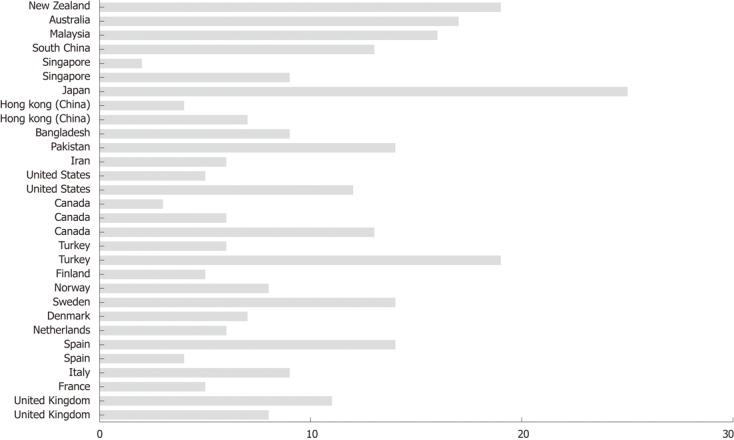

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects as many as 5%-20% of individuals worldwide (Figure 1)[1-31]. The annual incidence of IBS is between 196 and 260 per 100 000[32,33], with IBS occurring more often in women than in men, and being more commonly diagnosed in patients younger than 50 years of age[14,34-44]. IBS symptoms range from diarrhoea to constipation, or a combination of the two, with abdominal pain or discomfort existing alongside abdominal distension[45]. The degree of symptoms varies in different patients from tolerable to severe, and the time pattern and discomfort varies immensely from patient to patient[14,34-44]. Some patients complain of daily symptoms, while others report intermittent symptoms at intervals of weeks or months. IBS is not known to be associated with the development of serious disease or with excess mortality[46,47]. However, IBS causes a reduced quality of life with the same degree of impairment as major chronic diseases, such as diabetes, congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency and hepatic cirrhosis[48-50]. Although a minority (10%-50%) of IBS patients seek healthcare, they generate a substantial workload in both primary and secondary care[51-53]. The annual costs in the United States, both direct and indirect, for the management of patients with IBS are estimated at 15-30 billion USD[37,54,55].

Figure 1.

The prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to Rome criteria in different countries. Reproduced from reference [1] with permission from Nova Science Publisher, Inc.

The treatment options for IBS have included pharmacological symptomatic relief of symptoms such as pain, diarrhoea or constipation. Evidence of the long-term benefit of pharmacological agents has been sparse, and new agents that have proven to be effective have raised issues concerning safety[56,57]. Alternative therapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy, have been used with good results[58]. Other non-pharmacological approaches have been also tried with proven effects on symptoms and the quality of life in patients with IBS[58].

The present review is an attempt to give an update on the diagnosis and pathogenesis of IBS, and to discuss some controversial issues in both the diagnosis and pathogenesis of IBS.

DIAGNOSIS

There is currently no biochemical, histopathological or radiological diagnostic test for IBS, with the diagnosis of IBS being based mainly on symptom assessment. Over the last few years, Rome working parties have generated detailed, accurate, and clinically useful definitions of the syndrome. As a result, the Rome criteria (I, II and III) have been established (Table 1)[59,60]. In addition to these criteria, warning symptoms or red flags, such as age over 50 years, a short history of symptoms, nocturnal symptoms, weight loss, rectal bleeding, anaemia, and the presence of markers for inflammation or infections, should be excluded. IBS patients are sub-grouped on the basis of differences in the predominant bowel pattern as diarrhoea-predominant (IBS-D), constipation-predominant (IBS-C), or a mixture of both diarrhoea and constipation (IBS-M), and un-subtyped IBS in patients with an insufficient abnormality of stool consistency to meet the criteria for IBS C, D or M (Table 2). It has been reported that around one third of patients have IBS-D, one third have IBS-C, and the remainder have IBS-M[61-63]. The division of IBS patients into subtypes is useful for clinical practice and symptomatic treatment, but it is common for IBS patients to switch from one subtype to another over time. These patients are known as “alternators”. More than 75% of IBS patients change to either of the other 2 subtypes at least once over a 1-year period[63].

Table 1.

Rome III criteria for the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome1

| Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort with onset at least 6 mo prior to diagnosis, associated with 2 or more of the following, at least 3 d/mo in the last 3 mo |

| Improvement with defecation |

| Onset associated with change in frequency of stool |

| Onset associated with change in form (appearance) of stool |

| Symptoms that cumulatively support the diagnosis are: |

| Abnormal stool frequency (greater than 3 bowel movements per day or less than 3 bowels movements per week) |

| Abnormal stool form (lump/hard or loose/watery stool) |

| Abnormal stool passage (straining, urgency or feeling of incomplete evacuation) |

| Passage of mucous |

| Bloating or feeling of abdominal distension |

1Adapted from reference [1] with the permission from Nova Science Publisher, Inc.

Table 2.

Subtyping of irritable bowel syndrome1

| IBS with constipation-hard or lumpy stools > 25% and loos or watery stools < 25% of bowel movements |

| IBS with diarrhea-loos or watery stools > 25% and hard or lumpy stools stools < 25% of bowel movements |

| Mixed IBS-loos or watery stools > 25% and hard or lumpy stools stools > 25% of bowel movements |

| Unsubtyped IBS-insufficient abnormality of stool consistency to meet criteria for IBS-C,D or M |

1Adapted from reference [1] with the permission from Nova Science Publisher, Inc. IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-C: IBS with constipation; IBS-D: IBS with diarrhea-loos; IBS-M: IBS with a mixture of both diarrhoea and constipation.

The majority of gastroenterologists believe that a symptom-based diagnosis, such as that based on the Rome III criteria, without red flags is enough for the diagnosis of IBS and that no further investigations are needed. The use of red flags in combination with Rome criteria has been found to be highly specific, but not particularly sensitive[64]. The American College of Gastroenterology Task Force does not recommend routine colonoscopy in patients younger than 50 years of age without any associated alarming symptoms[65]. The guidelines of the of the British Society of Gastroenterology go further, however, by recommending an examination of the colon earlier if there is a first degree relative affected by colorectal cancer who is younger than 45 years, or two first degree relatives of any age[66]. The British Society Of Gastroenterology also recommended further investigations in IBS-D due to the overlap with other diarrhoea diseases, such as coeliac and inflammatory bowel disease (IBDs)[66]. These recommendations seem to be suitable for detecting and diagnosing colorectal cancer in this group of patients, but not in other organic gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. It is rather difficult to clinically distinguish IBS from adult-onset coeliac disease (CD)[67-73], as the breadth of the spectrum of symptoms associated with IBS results in a potential for overlap of IBS and CD symptomatologies. The situation is further complicated by the fact that the abdominal symptoms of both IBS and CD patients are triggered by the ingestion of wheat products. In CD patients, this is due to a gluten allergy, while in IBS the effect is attributed to the long sugar polymer fructan in the wheat[74]. The prevalence of CD in IBS varies in different studies and varies from 0.04% to 4.7%[72,73,75-84]. Regardless of the number of CD patients among patients diagnosed with IBS, I believe that IBS patients from all subtypes should be routinely screened for CD, which is in line with current opinions in the field[84-86]. Distinguishing IBD from IBS, especially with mild disease activity, can be difficult[87]. Furthermore, IBS-like symptoms are frequently reported before the diagnosis of IBD[87-90]. Microscopic colitis (MC) and IBS have similar symptoms and a normal endoscopic appearance[91-101], and the diagnostic overlap between IBS, IBD and MC is important because of a potentially different treatment for each disorder. The prevalence of IBD in patients that fulfilled the Rome criteria without alarming symptoms varies between 0.4% and 1.9%[96-100], and MC from 0.7% to 1.5%[90-97]. It is conceivable, therefore, to conclude that symptom-based diagnosis of IBS may lead to a number of other GI disorders that require quite different management than IBS being missed. Sigmoidoscopy in IBS patients might be insufficient, however, as a considerable number of MC patients may not be identified without mucosal biopsies from the right colon[101]. Moreover, performing a sigmoidoscopy would not exclude Crohn’s disease lesions in the terminal ileum, making ileocolonoscopy prefered, especially in IBS-D patients. This seems, at first sight, to add more economic burden to healthcare, which is already suffering from a lack of resources. IBS patients are already consuming a large amount of healthcare resources. However, performing an ileocolonoscopy would reassure IBS patients and prevent them from seeking a new examination, which would not increase the economic burden of this patient group on society, but instead use the existing resources effectively.

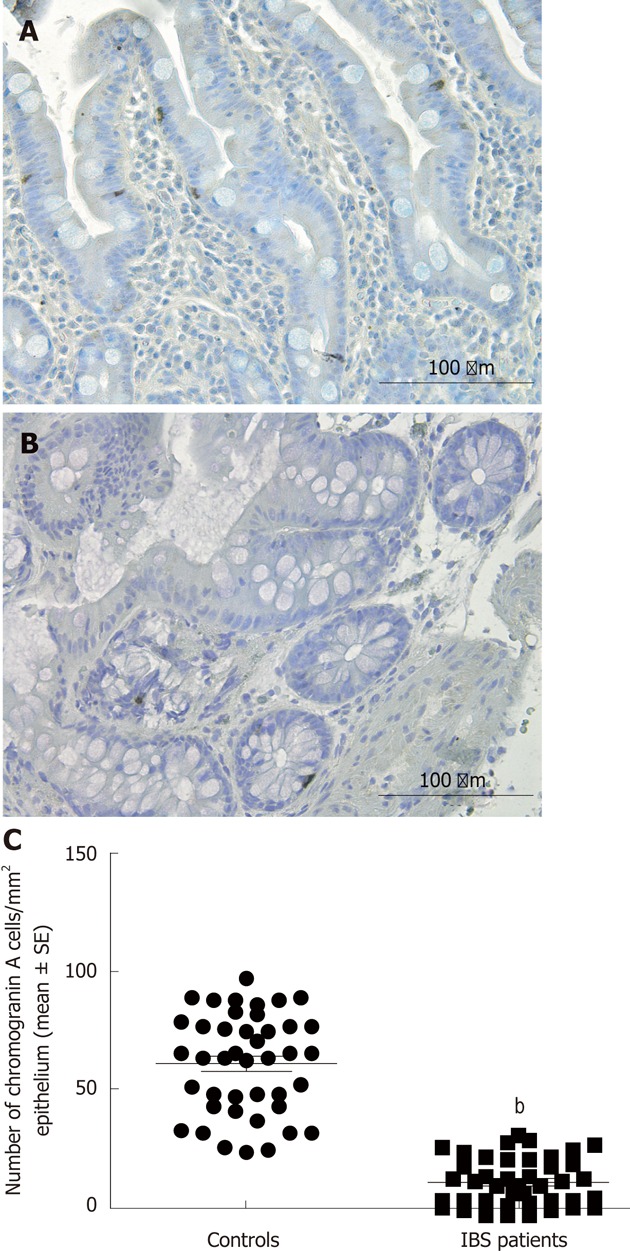

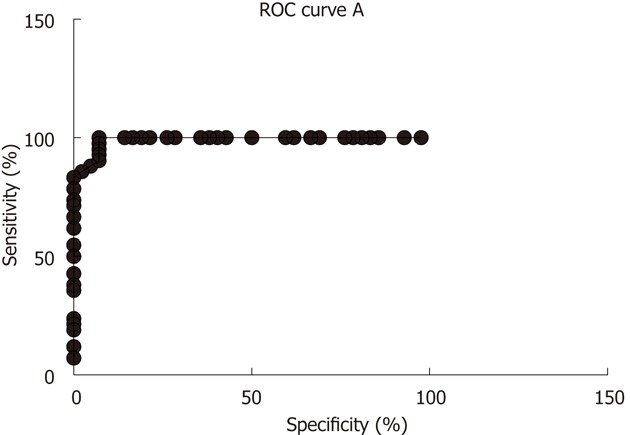

Several biomarkers for the diagnosis of IBS have been considered, but only gut transit measured by radio-isotope markers meets the criteria for reproducibility and availability[102]. However, radio-isotope tests themselves are expensive and of limited availability[102]. It has been reported that the chromogranin A-containing cell density is low in the duodenum of IBS patients (Figure 2)[103,104]. As chromogranin A is a general marker for endocrine cells[105,106], this finding indicates a general reduction in small intestinal endocrine cells in these patients. It has been proposed that the quantification of duodenal chromogranin A cell density could be used as a histopathological marker for the diagnosis of IBS[103,104]. Receiver-operator characteristic curves for chromogranin A cell density in the duodenum is given in Figure 3. The sensitivity and specificity at the cut-off < 31 cells/mm2 in the duodenum are 91% and 89%, respectively. Screening of IBS patients for CD is now widely accepted. Thus, gastroscopy with duodenal biopsies can be used for excluding or confirming CD instead of blood tests, and the same biopsies can be used for the diagnosis of IBS. The duodenal endocrine cell types affected and their role in the pathogenesis of IBS is discussed in the next section.

Figure 2.

Chromogranin A cells in the duodenum. A: A healthy subject; B: A patient with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); C: Controls and IBS patients. Reproduced from reference [1] with permission from Nova Science Publisher, Inc. bP < 0.01 vs control group.

Figure 3.

Receiver-operator characteristic for chromogranin A cell density in the duodenum. Reproduced from reference [1] with permission from Nova Science Publisher, Inc. ROC: Receiver-operator characteristic.

PATHOGENESIS

Patients with IBS typically present with GI complaints for which physicians can find no organic cause. It is natural and understandable to make comparisons with hysteria, which is also predominant in women. Hysteria has been replaced in modern psychiatry by somatisation disorders and conversion disorders. The notion that IBS is a psychiatric disorder is deeply rooted in clinical practice. This situation was not improved by the huge number of publications on a selected group of IBS patients, which show that IBS patients are more likely to be psychiatrically ill and sexually or physically abused than the general population[107-121]. Many patients with IBS ignore their symptoms and regard them as a normal part of everyday life. IBS patients with anxiety, depression, somatisation or hypochondria are more liable to seek healthcare than other IBS patients. Unless this is borne in mind, incorrect conclusions can be drawn. A hospital-based case-control study showed that patients with IBS have a comparable health-related quality of life, level of psychological distress and occurrence of recent stressful life events to age-matched IBD patients[122]. These findings are interesting as IBD patients receive effective treatment and are treated with sympathy, understanding and support by their doctors as well as society. In contrast, IBS patients are offered non-effective treatments, are treated with mistrust and neglect by their doctors, feel that they are labelled as hypochondriacs and believe that they receive no support from society. It could be expected that IBS patients would be more anxious and depressed than IBD patients, but this is not the case. Two percent of patients diagnosed with IBS among the adult residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, United States, were found to suffer from depression compared to the 16.2% incidence of depression in the entire population of the United States[122,123]. In conclusion, there is no convincing evidence to show that psychological factors play a role in the onset and/or progression of IBS[66].

The pathogenesis of IBS appears to be multifactorial. There is evidence to show that the following factors play a central role in the pathogenesis of IBS: heritability and genetics, environment and social learning, dietary or intestinal microbiota, low-grade inflammation and disturbances in the neuroendocrine system (NES) of the gut.

Heritability and genetics

Up to 33% of patients with IBS had a family history of IBS compared to 2% of the controls[124]. In a study of a family cluster from Olmsted County, United States, a significant association was reported between having a first degree family member with bowel symptoms and presenting with IBS. In contrast, those who reported having a spouse with bowel symptoms were no more likely to present with IBS than the general population[125]. It was further shown that the prevalence of IBS was 17% in the relatives of patients compared to 7% in the relatives of spouses[126]. Another study showed that patients with IBS were more likely to present a family history of IBS than controls (33.9% and 12.6%, respectively). Moreover, 21.1% of IBS non-consulter patients reported a family history of IBS, in comparison with 12.6% of the control subjects[127].

In twin studies, a higher rate of IBS was reported in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins (33.3% vs 13.3%). Moreover, 56.9% of the variance was attributed to additive genetic factors, indicating a substantial genetic component in IBS[128-132]. In contrast, a study performed on British twin pairs did not show any significance in the rates of IBS between monozygotic and dizygotic twins[133].

The serotonin transporter (SERT) gene encoding the SERT protein is located on chromosome 17q11.1-q12. A functional polymorphism is the insertion or a deletion of 44 base pairs in the SERT-gene-linked polymorphic region[134]. An association was reported between a functional polymorphism in the SERT gene and diarrhoea-predominant IBS[135,136]. Individuals with a long allele genotype of the SERT gene have been shown to be vulnerable to developing IBS with constipation[137]. Other studies, however, did not show such association between SERT-gene polymorphism and IBS[136]. A polymorphism in the CCK1 receptor CCKAR gene (779T>C) has also been found to be associated with IBS[138,139].

Environment and social learning

Parental modelling and the reinforcement of illness behaviour can contribute to the causes of IBS[140-144]. Having a mother with IBS has been shown to account for as much variance as having an identical set of genes as a co-twin who has IBS. This suggests that the contribution of social learning to IBS is at least as great as the contribution of heredity[144].

Dietary and intestinal flora

Patients with IBS believe that their diet has a significant influence on their symptoms and they are interested in finding out which foods they should avoid[145-148]. About 60% of IBS patients report a worsening of symptoms following food ingestion: 28% within 15 min after eating and 93% within 3 h[148]. Many IBS patients report specific foods as triggers, most commonly implicating milk and dairy products, wheat products, onion, peas and beans, hot spices, cabbage, certain meats, smoked products, fried food and caffeine as the offending foods[149]. However, dietary composition among IBS patients in the community does not differ from community controls[150-153]. In a recent study, IBS patients were reported to have made a conscious choice to avoid certain food items, some of which belong to fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs). However, they reported a higher consumption of other food items that are rich in FODMAPs. Patients also reportedly avoided other food sources that are important for health, which result in a low intake of calcium, phosphorus and vitamin B2[153].

There is no documented evidence showing that a food allergy or intolerance plays a role in IBS symptoms[1]. The reaction of IBS patients to certain food items has been attributed to a number of short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed so that a significant portion of the ingested carbohydrates enters the distal small bowel and colon. Once there they increase the osmotic pressure and provide a substrate for bacterial fermentation with the production of gas, distension of the large intestine and abdominal discomfort or pain. These carbohydrates are FODMAPs and include fructose, lactose, fructans, galactans and sugar alcohols, such as sorbitol, maltitol, mannitol, xylitol and ismalt. Fructose and lactose are present in apples, pears, watermelon, honey, fruit juices, dried fruits, milk and dairy products. Polyols are used in low calorie food products. Galactans and fructans are present in common dietary constituents, such as wheat, rye, garlic, onions, legumes, cabbage, artichokes, leeks, asparagus, lentils, inulin, soy, Brussels sprouts and broccoli[78,147].

A deficiency in dietary fibre was widely believed to be the primary cause of IBS[154]. Although increasing the amount of dietary fibre continues to be a standard recommendation for patients with IBS, clinical practice has shown that increased fibre intake in these patients increases abdominal pain, bloating and distension. IBS patients assigned to the fibre treatment showed persistent symptoms or no improvement in symptoms after treatment compared to patients taking the placebo or a low-fibre diet. Other studies have shown that whilst a water-insoluble fibre intake did not improve IBS symptoms, soluble-fibre intake was effective in improving overall IBS symptoms[155,156]. It is noteworthy that the role of FODMAPs and fibre on IBS symptoms is associated with intestinal flora. The presence of bacteria that break down FODMAPs and fibre and produce gas, such as Clostridia spp., can cause distension of the large intestine with abdominal discomfort or pain.

Most bacteria in the GI tract exist in the colon. The colon of each individual contains between 300 and 500 different species of bacteria[1], and each person has his own unique intestinal flora. The intestinal flora is affected by several factors, such as diet, climate changes, stress, illness, aging and antibiotic treatment[1]. The intestinal flora in IBS patients has been found to differ considerably from that of healthy controls, as IBS patients have fewer Lactobacillus and Bifdobacterium spp. than healthy subjects[157]. These bacteria bind to epithelial cells and inhibit pathogen binding as well as enhancing barrier functioning[158]. Furthermore, these bacterial species do not produce gas upon fermenting carbohydrates, which is an effect that would be amplified as they also inhibit the Clostridia spp.[158]. Probiotics alter colonic fermentation and stabilise the colonic microbiota, and several studies on probiotics have shown improvements in flatulence and abdominal distension, with a reduction in the composite IBS symptom score[158-160].

Low-grade inflammation

In a subset of IBS patients GI symptoms appear following gastroenteritis, with about 25% of patients showing IBS-D symptoms 6 mo post-infection and approximately 10% developing persistent symptoms[161-164]. Post-infectious (PI)-IBS has been reported after viral, bacterial, protozoa and nematode infections[1], with the incidence of PI-IBS varying between 7% and 31%, although the largest studies suggest this number is about 10%[161-164]. One study showed that 6% to 17% of sporadic (unselected) IBS patients believed that their symptoms began with an infection[1]. Following infection, the initial inflammatory response shows an increase in CD3 lymphocytes, CD8 intraepithelial lymphocytes and calprotectin-positive macrophages[161]. These changes rapidly decrease in most subjects but a small number with persistent symptoms fail to show this decline[165]. Furthermore, the number of serotonin cells was shown to increase in subjects with persistent symptoms[165]. There are several pieces of evidence showing that inflammation and immune cells affect the NES of the gut, which controls and regulates GI motility and sensitivity[166]. Thus, serotonin secretion by enterochromaffin (EC) cells can be enhanced or attenuated by the secretory products of immune cells such as CD4+T[167]. Furthermore, serotonin modulates the immune response[167]. The EC cells are in contact with or very close to CD3+ and CD20+ lymphocytes, and several serotonergic receptors have been characterised in lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells[168]. Moreover, immune cells in the small and large intestine show receptors for substance P and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide[169].

IBS occurs in 32%-46% of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and in 42%-60% of Crohn’s disease patients who are in remission[170-174]. Faecal calprotectin has been found to be significantly elevated in UC and Crohn’s disease patients with criteria for IBS, compared to those without IBS-type symptoms, indicating the presence of occult inflammation[174].

Abnormalities in the NEC of the gut in IBS

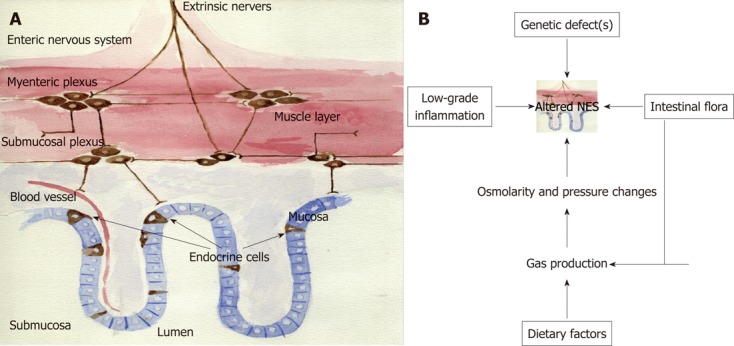

The NES of the gut consists of two parts: endocrine cells scattered among the epithelial cells of the mucosa facing the gut lumen, and peptidergic, serotonergic and nitric oxide-containing nerves of the enteric nervous system (ENS) in the gut wall (Figure 4A)[1]. This system regulates several functions of the GI tract, such as motility, secretion, absorption, microcirculation in the gut, local immune defence and cell proliferation[1]. This regulatory system includes a large number of neuroendocrine peptides/amines, which exert their effects via a number of actions: an endocrine mode of action, by circulating in the blood to reach distant targets, an autocrine/paracrine mode, which is a local action, and via synaptic signalling or via neuroendocrine means, which involve the release from synapses into the circulating blood. The different parts of this system interact and integrate with each other and with afferent and efferent nerve fibres of the central nervous system, in particular the autonomic nervous system. There are at least 14 different populations of endocrine or paracrine cells in the GI tract[1]. The ENS comprises a large variety of neurotransmitters and associated receptors. Almost every known neurotransmitter can be found in the ENS, and most of the receptors associated with these neurotransmitters are also expressed there[1].

Figure 4.

Schematic drawing to illustrate the neuroendocrine system of the gut and the possible pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome. A: Schematic drawing of neuroendocrine system; B: Possible pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome. Reproduced from reference [1] with permission from Nova Science Publisher, Inc. NES: Neuroendocrine system.

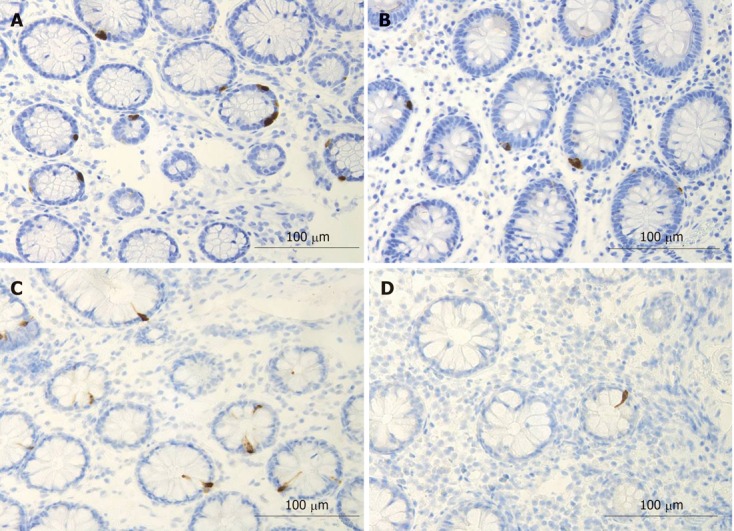

In the stomach of patients with IBS, the density of ghrelin-immunoreactive cells in the oxyntic mucosa was found to be significantly lower in IBS-constipation patients and significantly higher in IBS-diarrhoea patients compared to healthy controls[175]. However, the levels of total or active ghrelin in plasma and stomach tissue extracts from IBS patients did not differ from those of healthy subjects[175,176]. Ghrelin is a 28-amino acid peptide hormone that was originally isolated from the stomach[177]. Ghrelin mostly originates from endocrine cells in the oxyntic mucosa of the stomach, but small amounts are expressed in the small intestine, large intestine and in the arcuated nucleus of the hypothalamus[177]. Ghrelin has several functions, including a role in regulating growth hormone (GH) release from the pituitary, where it acts synergistically with the GH-releasing hormone[178,179]. Ghrelin also increases appetite and feeding and plays a major role in energy metabolism[178-181]. Furthermore, this hormone has been found to accelerate gastric and small and large intestinal motility[181-192], as well as having anti-inflammatory actions and protecting the gut against a wide range of insults. The density of neuropeptide-expressing cells is altered in the small intestine of IBS patients. Thus, the density of cells expressing gastric inhibitory polypeptide and somatostatin is decreased in patients with both diarrhoea- and constipation-predominant IBS subtypes[193]. The densities of secretin and cholecystokinin (CCK)-expressing cells are decreased in the diarrhoea-predominant subtype, but not in the constipation-predominant subtype. Serotonin cell density has also been found to be unchanged in the duodenum of IBS patients, regardless of the subtype[193], which is interesting as serotonin cells were previously reported to be affected in the small intestine of IBS patients[194-196]. These peptides all play important roles in secretion and gastric motility. In the large intestine, serotonin and polypeptide YY (PYY) cell densities have been found to be low in both IBS-constipation and IBS-diarrhoea patients (Figure 5)[197]. Furthermore, the mucosal 5-HT concentration has also been reported to be low in IBS patients[197], which is in line with current observations. In PI-IBS, the number of CCK and serotonin cells has been reported to be increased in the small intestine[198], and serotonin and PYY cell numbers were found to be increased in the large intestine[199-202].

Figure 5.

Serotonin cells and polypeptide YY immunoreactive cells in the colon. A: A healthy control in serotonin cells; B: A patient with irritable bowel syndrome in serotonin cells; C: A healthy subject in polypeptide YY (PYY) immunoreactive cells; D: An irritable bowel syndrome patient in PYY immunoreactive cells. Reproduced from reference 1 with permission from Nova Science Publisher, Inc.

HYPOTHESIS

As described above, abnormalities in the neuroendocrine peptides/amines of the gut have been reported. These abnormalities could cause disturbances in digestion, GI motility and visceral hypersensitivity. These abnormalities appear to contribute to symptom development and could play a central role in the pathogenesis of IBS. Genetic differences have been found between IBS patients and healthy subjects in genes controlling the serotonin signalling system and CCK. Moreover, differences in the diet, intestinal flora and inflammation affect the NES of the gut. The release of different gut hormones depends on the composition and quantity of ingested food, as the food content of FODMAPs and fibre, intestinal flora and the subsequent fermentation can increase intestinal osmotic pressure. This change in intestinal pressure can stimulate hormonal release, such as the release of serotonin. Likewise, inflammation and the release of secretory products from immune cells effects hormonal release and the proliferation of gut endocrine cells.

Therefore, it is feasible to hypothesise that the cause of IBS is an altered NES (Figure 4B). An altered NES would cause abnormal GI motility, secretion and sensation, all of which are characteristic of IBS[203-216]. The alteration in NES could be a result of one or more of the following: genetic factors, dietary intake, intestinal flora or low-grade inflammation.

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of IBS is based on symptom assessment and the Rome III criteria. Whereas the latter has been widely used in scientific studies and in GI congresses in the past 10 years, it is not, however, used by most clinicians consulted by IBS patients[217-220]. This is not because these clinicians are unaware of the Rome III criteria, but because of the reality in the clinic. IBS patients that seek advice from a doctor are worried and want to be investigated, and are rarely satisfied until this is done, so they will repeatedly seek healthcare until they are investigated. I believe, therefore, that the Rome III criteria should be combined with a physical examination, blood tests, gastroscopy, duodenal biopsies and colonoscopy with segmental biopsies. These examinations and tests, in addition to the Rome III criteria, would reassure the patient and exclude CD, IBD, MC and cancer. Furthermore, performing these examinations and tests would remove the pressure applied by some patients to perform these examinations repeatedly, as the need for further investigations can always be argued against if there are no new symptoms. Duodenal chromogranin A cell density also appears to be a promising biomarker for the diagnosis of IBS.

The pathogenesis of IBS appears to be multifactorial. There is evidence to suggest that the following factors play a central role in the pathogenesis of IBS: heritability and genetics, dietary and intestinal microbiota, low-grade inflammation and disturbances in the NEC of the gut. Several authors have tried to connect these factors in a logical cause-effect pattern, but it is my belief that the proposed hypothesis presented in this review is the most logical.

Footnotes

Supported by Grants from Helse-Fonna

Peer reviewers: Richard Alexander Awad, Professor, Experimental Medicine and Motility Unit, Mexico City General Hospital, 06726 Mexico City, Mexico; Kwang Jae Lee, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Ajou University Hospital, San 5, Woncheondong, Yeongtongku, Suwon 443-721, South Korea

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

References

- 1.El-Salhy M, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Irritable bowel syndrome. New York: Nova scientific Publisher; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley EM, Locke GR, Mueller-Lissner S, Paulo LG, Tytgat GN, Helfrich I, Schaefer E. Prevalence and management of abdominal cramping and pain: a multinational survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:411–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vandvik PO, Lydersen S, Farup PG. Prevalence, comorbidity and impact of irritable bowel syndrome in Norway. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:650–656. doi: 10.1080/00365520500442542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, Temple RD, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE, Janssens J, Funch-Jensen P, Corazziari E. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–1580. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito YA, Talley NJ, J Melton L, Fett S, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR. The effect of new diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome on community prevalence estimates. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:687–694. doi: 10.1046/j.1350-1925.2003.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Rance L. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in Canada: first population-based survey using Rome II criteria with suggestions for improving the questionnaire. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:225–235. doi: 10.1023/a:1013208713670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li FX, Patten SB, Hilsden RJ, Sutherland LR. Irritable bowel syndrome and health-related quality of life: a population-based study in Calgary, Alberta. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:259–263. doi: 10.1155/2003/706891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyce PM, Koloski NA, Talley NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome according to varying diagnostic criteria: are the new Rome II criteria unnecessarily restrictive for research and practice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3176–3183. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbezat G, Poulton R, Milne B, Howell S, Fawcett JP, Talley N. Prevalence and correlates of irritable bowel symptoms in a New Zealand birth cohort. N Z Med J. 2002;115:U220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boekema PJ, van Dam van Isselt EF, Bots ML, Smout AJ. Functional bowel symptoms in a general Dutch population and associations with common stimulants. Neth J Med. 2001;59:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(01)00128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mearin F, Badía X, Balboa A, Baró E, Caldwell E, Cucala M, Díaz-Rubio M, Fueyo A, Ponce J, Roset M, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome prevalence varies enormously depending on the employed diagnostic criteria: comparison of Rome II versus previous criteria in a general population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1155–1161. doi: 10.1080/00365520152584770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaburri M, Bassotti G, Bacci G, Cinti A, Bosso R, Ceccarelli P, Paolocci N, Pelli MA, Morelli A. Functional gut disorders and health care seeking behavior in an Italian non-patient population. Recenti Prog Med. 1989;80:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffin B, Dapoigny M, Cloarec D, Comet D, Dyard F. Relationship between severity of symptoms and quality of life in 858 patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:11–15. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(04)94834-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agréus L, Svärdsudd K, Nyrén O, Tibblin G. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:671–680. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hillilä MT, Färkkilä MA. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to different diagnostic criteria in a non-selected adult population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:339–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kay L, Jørgensen T, Jensen KH. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in a random population: prevalence, incidence, natural history and risk factors. J Intern Med. 1994;236:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1994.tb01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoseini-Asl MK, Amra B. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Shahrekord, Iran. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2003;22:215–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karaman N, Türkay C, Yönem O. Irritable bowel syndrome prevalence in city center of Sivas. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2003;14:128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celebi S, Acik Y, Deveci SE, Bahcecioglu IH, Ayar A, Demir A, Durukan P. Epidemiological features of irritable bowel syndrome in a Turkish urban society. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:738–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masud MA, Hasan M, Khan AK. Irritable bowel syndrome in a rural community in Bangladesh: prevalence, symptoms pattern, and health care seeking behavior. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1547–1552. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huerta I, Valdovinos MA, Schmulson M. Irritable bowel syndrome in Mexico. Dig Dis. 2001;19:251–257. doi: 10.1159/000050688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwan AC, Hu WH, Chan YK, Yeung YW, Lai TS, Yuen H. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Hong Kong. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1180–1186. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau EM, Chan FK, Ziea ET, Chan CS, Wu JC, Sung JJ. Epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in Chinese. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2621–2624. doi: 10.1023/a:1020549118299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlemper RJ, van der Werf SD, Vandenbroucke JP, Biemond I, Lamers CB. Peptic ulcer, non-ulcer dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome in The Netherlands and Japan. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993;200:33–41. doi: 10.3109/00365529309101573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho KY, Kang JY, Seow A. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in a multiracial Asian population, with particular reference to reflux-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1816–1822. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong LS, Chen MH, Chen HX, Xu AG, Wang WA, Hu PJ. A population-based epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syndrome in South China: stratified randomized study by cluster sampling. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1217–1224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gwee KA, Wee S, Wong ML, Png DJ. The prevalence, symptom characteristics, and impact of irritable bowel syndrome in an asian urban community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:924–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajendra S, Alahuddin S. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:704–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jafri W, Yakoob J, Jafri N, Islam M, Ali QM. Irritable bowel syndrome and health seeking behaviour in different communities of Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:285–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jafri W, Yakoob J, Jafri N, Islam M, Ali QM. Frequency of irritable bowel syndrome in college students. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2005;17:9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boivin M. Socioeconomic impact of irritable bowel syndrome in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15 Suppl B:8B–11B. doi: 10.1155/2001/401309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Locke GR, Yawn BP, Wollan PC, Melton LJ, Lydick E, Talley NJ. Incidence of a clinical diagnosis of the irritable bowel syndrome in a United States population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1025–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.García Rodríguez LA, Ruigómez A, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Olbe L. Detection of colorectal tumor and inflammatory bowel disease during follow-up of patients with initial diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:306–311. doi: 10.1080/003655200750024191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson WG, Heaton KW. Functional bowel disorders in apparently healthy people. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy TM, Jones RH, Hungin AP, O’flanagan H, Kelly P. Irritable bowel syndrome, gastro-oesophageal reflux, and bronchial hyper-responsiveness in the general population. Gut. 1998;43:770–774. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.6.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talley NJ, Gabriel SE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW. Medical costs in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1736–1741. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hungin AP, Whorwell PJ, Tack J, Mearin F. The prevalence, patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40,000 subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:643–650. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones R, Lydeard S. Irritable bowel syndrome in the general population. BMJ. 1992;304:87–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6819.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bordie AK. Functional disorders of the colon. J Indian Med Assoc. 1972;58:451–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Keefe EA, Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Jacobsen SJ. Bowel disorders impair functional status and quality of life in the elderly: a population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50:M184–M189. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.4.m184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Everhart JE, Renault PF. Irritable bowel syndrome in office-based practice in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:998–1005. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90275-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson S, Roberts L, Roalfe A, Bridge P, Singh S. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: a community survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:495–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harvey RF, Salih SY, Read AE. Organic and functional disorders in 2000 gastroenterology outpatients. Lancet. 1983;1:632–634. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spiegel BM. The burden of IBS: looking at metrics. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:265–269. doi: 10.1007/s11894-009-0039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Systematic review on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in the European Union. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19 Suppl 1:S11–S37. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000252641.64656.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drossman DA, Morris CB, Schneck S, Hu YJ, Norton NJ, Norton WF, Weinland SR, Dalton C, Leserman J, Bangdiwala SI. International survey of patients with IBS: symptom features and their severity, health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:541–550. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318189a7f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sloth H, Jørgensen LS. Chronic non-organic upper abdominal pain: diagnostic safety and prognosis of gastrointestinal and non-intestinal symptoms. A 5- to 7-year follow-up study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988;23:1275–1280. doi: 10.3109/00365528809090204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller V, Whitaker K, Morris JA, Whorwell PJ. Gender and irritable bowel syndrome: the male connection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:558–560. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200408000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitehead WE, Burnett CK, Cook EW, Taub E. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:2248–2253. doi: 10.1007/BF02071408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:654–660. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.16484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schuster MM. Defining and diagnosing irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7:S246–S251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey 1989: Digestive Disorders Supplement. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mitchell CM, Drossman DA. Survey of the AGA membership relating to patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1282–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(87)91099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, Adams E, Cronin K, Goodman C, Gemmen E, Shah S, Avdic A, Rubin R. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500–1511. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spanier JA, Howden CW, Jones MP. A systematic review of alternative therapies in the irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:265–274. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pasricha PJ. Desperately seeking serotonin... A commentary on the withdrawal of tegaserod and the state of drug development for functional and motility disorders. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2287–2290. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wald A, Rakel D. Behavioral and complementary approaches for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23:284–292. doi: 10.1177/0884533608318677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schmulson MJ, Ortiz-Garrido OM, Hinojosa C, Arcila D. A single session of reassurance can acutely improve the self-perception of impairment in patients with IBS. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Müller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II43–II47. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mearin F, Balboa A, Badía X, Baró E, Caldwell E, Cucala M, Díaz-Rubio M, Fueyo A, Ponce J, Roset M, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes according to bowel habit: revisiting the alternating subtype. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:165–172. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200302000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tillisch K, Labus JS, Naliboff BD, Bolus R, Shetzline M, Mayer EA, Chang L. Characterization of the alternating bowel habit subtype in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:896–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Drossman DA, Morris CB, Hu Y, Toner BB, Diamant N, Leserman J, Shetzline M, Dalton C, Bangdiwala SI. A prospective assessment of bowel habit in irritable bowel syndrome in women: defining an alternator. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:580–589. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Feld AD, Levy RL, VON Korff M, Turner MJ, Drossman DA. Utility of red flag symptom exclusions in the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:137–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld PS, Spiegel BM, Talley NJ, Quigley EM. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104 Suppl 1:S1–35. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, Emmanuel A, Houghton L, Hungin P, Jones R, Kumar D, Rubin G, Trudgill N, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56:1770–1798. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sanders DS, Carter MJ, Hurlstone DP, Pearce A, Ward AM, McAlindon ME, Lobo AJ. Association of adult coeliac disease with irritable bowel syndrome: a case-control study in patients fulfilling ROME II criteria referred to secondary care. Lancet. 2001;358:1504–1508. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06581-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zipser RD, Patel S, Yahya KZ, Baisch DW, Monarch E. Presentations of adult celiac disease in a nationwide patient support group. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:761–764. doi: 10.1023/a:1022897028030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wahnschaffe U, Ullrich R, Riecken EO, Schulzke JD. Celiac disease-like abnormalities in a subgroup of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1329–1338. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bottaro G, Cataldo F, Rotolo N, Spina M, Corazza GR. The clinical pattern of subclinical/silent celiac disease: an analysis on 1026 consecutive cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:691–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Green PHR SN, Panagi SG, Goldstein SL, Mcmahon DJ, Absan H, Neugut AI. Characteristics of adult celiac disease in the USA: results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:126–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lo W, Sano K, Lebwohl B, Diamond B, Green PH. Changing presentation of adult celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:395–398. doi: 10.1023/a:1021956200382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.El-Salhy M, Lomholt-Beck B, Gundersen D. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Report. 2011;4:403–405. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, Not T, Colletti RB, Drago S, Elitsur Y, Green PH, Guandalini S, Hill ID, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:286–292. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eswaran S, Tack J, Chey WD. Food: the forgotten factor in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40:141–162. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van der Wouden EJ, Nelis GF, Vecht J. Screening for coeliac disease in patients fulfilling the Rome II criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in a secondary care hospital in The Netherlands: a prospective observational study. Gut. 2007;56:444–445. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.112052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Locke GR, Murray JA, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, Talley NJ. Celiac disease serology in irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia: a population-based case-control study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:476–482. doi: 10.4065/79.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hin H, Bird G, Fisher P, Mahy N, Jewell D. Coeliac disease in primary care: case finding study. BMJ. 1999;318:164–167. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7177.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shahbazkhani B, Forootan M, Merat S, Akbari MR, Nasserimoghadam S, Vahedi H, Malekzadeh R. Coeliac disease presenting with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:231–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Catassi C, Kryszak D, Louis-Jacques O, Duerksen DR, Hill I, Crowe SE, Brown AR, Procaccini NJ, Wonderly BA, Hartley P, et al. Detection of Celiac disease in primary care: a multicenter case-finding study in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1454–1460. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Korkut E, Bektas M, Oztas E, Kurt M, Cetinkaya H, Ozden A. The prevalence of celiac disease in patients fulfilling Rome III criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2010;21:389–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sanders DS, Patel D, Stephenson TJ, Ward AM, McCloskey EV, Hadjivassiliou M, Lobo AJ. A primary care cross-sectional study of undiagnosed adult coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:407–413. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200304000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Verdu EF, Armstrong D, Murray JA. Between celiac disease and irritable bowel syndrome: the “no man’s land” of gluten sensitivity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1587–1594. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wahnschaffe U, Schulzke JD, Zeitz M, Ullrich R. Predictors of clinical response to gluten-free diet in patients diagnosed with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:844–850; quiz 769. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Monsbakken KW, Vandvik PO, Farup PG. Perceived food intolerance in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome-- etiology, prevalence and consequences. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:667–672. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Young E, Stoneham MD, Petruckevitch A, Barton J, Rona R. A population study of food intolerance. Lancet. 1994;343:1127–1130. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schoepfer AM, Trummler M, Seeholzer P, Seibold-Schmid B, Seibold F. Discriminating IBD from IBS: comparison of the test performance of fecal markers, blood leukocytes, CRP, and IBD antibodies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:32–39. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bercik P, Verdu EF, Collins SM. Is irritable bowel syndrome a low-grade inflammatory bowel disease? Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:235–245, vi-vii. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Burgmann T, Clara I, Graff L, Walker J, Lix L, Rawsthorne P, McPhail C, Rogala L, Miller N, Bernstein CN. The Manitoba Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort Study: prolonged symptoms before diagnosis--how much is irritable bowel syndrome? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–2131. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Limsui D, Pardi DS, Camilleri M, Loftus EV, Kammer PP, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ. Symptomatic overlap between irritable bowel syndrome and microscopic colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:175–181. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Barta Z, Mekkel G, Csípo I, Tóth L, Szakáll S, Szabó GG, Bakó G, Szegedi G, Zeher M. Microscopic colitis: a retrospective study of clinical presentation in 53 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1351–1355. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Madisch A, Bethke B, Stolte M, Miehlke S. Is there an association of microscopic colitis and irritable bowel syndrome--a subgroup analysis of placebo-controlled trials. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6409. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i41.6409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kao KT, Pedraza BA, McClune AC, Rios DA, Mao YQ, Zuch RH, Kanter MH, Wirio S, Conteas CN. Microscopic colitis: a large retrospective analysis from a health maintenance organization experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3122–3127. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yantiss RK, Odze RD. Optimal approach to obtaining mucosal biopsies for assessment of inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:774–783. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Frissora CL, Koch KL. Symptom overlap and comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other conditions. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7:264–271. doi: 10.1007/s11894-005-0018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.El-Salhy M, Halwe J, Lomholt-Beck B, Gundersen D. The prevalence of inflammatory bowel diseases and microscopic colitis and colorectal cancer in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Insights. 2011;3:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tolliver BA, Herrera JL, DiPalma JA. Evaluation of patients who meet clinical criteria for irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:176–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hamm LR, Sorrells SC, Harding JP, Northcutt AR, Heath AT, Kapke GF, Hunt CM, Mangel AW. Additional investigations fail to alter the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome in subjects fulfilling the Rome criteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1279–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vanner SJ, Depew WT, Paterson WG, DaCosta LR, Groll AG, Simon JB, Djurfeldt M. Predictive value of the Rome criteria for diagnosing the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2912–2917. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.MacIntosh DG, Thompson WG, Patel DG, Barr R, Guindi M. Is rectal biopsy necessary in irritable bowel syndrome? Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1407–1409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Spiller RC. Potential biomarkers. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40:121–139. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.El-Salhy M, Lomholt-Beck B, Hausken T. Chromogranin A as a possible tool in the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1435–1439. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.503965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.El-Salhy M, Seim I, Chopin L, Gundersen D, Hatlebakk JG, Hausken T. Irritable bowel syndrome: the role of gut neuroendocrine peptides. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:2783–2800. doi: 10.2741/e583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Taupenot L, Harper KL, O’Connor DT. The chromogranin-secretogranin family. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1134–1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wiedenmann B, Huttner WB. Synaptophysin and chromogranins/secretogranins--widespread constituents of distinct types of neuroendocrine vesicles and new tools in tumor diagnosis. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1989;58:95–121. doi: 10.1007/BF02890062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sykes MA, Blanchard EB, Lackner J, Keefer L, Krasner S. Psychopathology in irritable bowel syndrome: support for a psychophysiological model. J Behav Med. 2003;26:361–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1024209111909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pan G, Lu S, Ke M, Han S, Guo H, Fang X. Epidemiologic study of the irritable bowel syndrome in Beijing: stratified randomized study by cluster sampling. Chin Med J (Engl) 2000;113:35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bennett EJ, Piesse C, Palmer K, Badcock CA, Tennant CC, Kellow JE. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: psychological, social, and somatic features. Gut. 1998;42:414–420. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.3.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.North CS, Downs D, Clouse RE, Alrakawi A, Dokucu ME, Cox J, Spitznagel EL, Alpers DH. The presentation of irritable bowel syndrome in the context of somatization disorder. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:787–795. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1140–1156. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Nachman G, Li ZM, Gluck H, Toomey TC, Mitchell CM. Sexual and physical abuse in women with functional or organic gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:828–833. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-11-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms and self-reported abuse: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1040–1049. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR. Self-reported abuse and gastrointestinal disease in outpatients: association with irritable bowel-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:366–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Walker EA, Gelfand AN, Gelfand MD, Katon WJ. Psychiatric diagnoses, sexual and physical victimization, and disability in patients with irritable bowel syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease. Psychol Med. 1995;25:1259–1267. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Drossman DA. Abuse, trauma, and GI illness: is there a link? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:14–25. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Drossman DA, Li Z, Toner BB, Diamant NE, Creed FH, Thompson D, Read NW, Babbs C, Barreiro M, Bank L. Functional bowel disorders. A multicenter comparison of health status and development of illness severity index. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:986–995. doi: 10.1007/BF02064187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Leserman J, Li Z, Drossman DA, Toomey TC, Nachman G, Glogau L. Impact of sexual and physical abuse dimensions on health status: development of an abuse severity measure. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:152–160. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199703000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Talley NJ, Boyce PM, Jones M. Is the association between irritable bowel syndrome and abuse explained by neuroticism? A population based study. Gut. 1998;42:47–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Davidoff AL, Palsson OS, Schuster MM. Pain from rectal distension in women with irritable bowel syndrome: relationship to sexual abuse. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:796–804. doi: 10.1023/a:1018820315549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ringel Y, Whitehead WE, Toner BB, Diamant NE, Hu Y, Jia H, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA. Sexual and physical abuse are not associated with rectal hypersensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2004;53:838–842. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.021725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Pace F, Molteni P, Bollani S, Sarzi-Puttini P, Stockbrügger R, Bianchi Porro G, Drossman DA. Inflammatory bowel disease versus irritable bowel syndrome: a hospital-based, case-control study of disease impact on quality of life. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1031–1038. doi: 10.1080/00365520310004524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Whorwell PJ, McCallum M, Creed FH, Roberts CT. Non-colonic features of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1986;27:37–40. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Locke GR, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Melton LJ. Familial association in adults with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:907–912. doi: 10.4065/75.9.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kalantar JS, Locke GR, Zinsmeister AR, Beighley CM, Talley NJ. Familial aggregation of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Gut. 2003;52:1703–1707. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.12.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kanazawa M, Endo Y, Whitehead WE, Kano M, Hongo M, Fukudo S. Patients and nonconsulters with irritable bowel syndrome reporting a parental history of bowel problems have more impaired psychological distress. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1046–1053. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000034570.52305.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Morris-Yates A, Talley NJ, Boyce PM, Nandurkar S, Andrews G. Evidence of a genetic contribution to functional bowel disorder. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1311–1317. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.440_j.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Levy RL, Jones KR, Whitehead WE, Feld SI, Talley NJ, Corey LA. Irritable bowel syndrome in twins: heredity and social learning both contribute to etiology. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:799–804. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lembo A, Zaman M, Jones M, Talley NJ. Influence of genetics on irritable bowel syndrome, gastro-oesophageal reflux and dyspepsia: a twin study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1343–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wojczynski MK, North KE, Pedersen NL, Sullivan PF. Irritable bowel syndrome: a co-twin control analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2220–2229. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bengtson MB, Rønning T, Vatn MH, Harris JR. Irritable bowel syndrome in twins: genes and environment. Gut. 2006;55:1754–1759. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.097287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mohammed I, Cherkas LF, Riley SA, Spector TD, Trudgill NJ. Genetic influences in irritable bowel syndrome: a twin study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1340–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hotoleanu C, Popp R, Trifa AP, Nedelcu L, Dumitrascu DL. Genetic determination of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6636–6640. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Yeo A, Boyd P, Lumsden S, Saunders T, Handley A, Stubbins M, Knaggs A, Asquith S, Taylor I, Bahari B, et al. Association between a functional polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene and diarrhoea predominant irritable bowel syndrome in women. Gut. 2004;53:1452–1458. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Camilleri M. Is there a SERT-ain association with IBS? Gut. 2004;53:1396–1399. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.039826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Li Y, Nie Y, Xie J, Tang W, Liang P, Sha W, Yang H, Zhou Y. The association of serotonin transporter genetic polymorphisms and irritable bowel syndrome and its influence on tegaserod treatment in Chinese patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2942–2949. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9679-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Park SY, Rew JS, Lee SM, Ki HS, Lee KR, Cheo JH, Kim HI, Noh DY, Joo YE, Kim HS, et al. Association of CCK(1) Receptor Gene Polymorphisms and Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Korean. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:71–76. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2010.16.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.D’Amato M, Rovati LC. Cholecystokinin-A receptor antagonists: therapies for gastrointestinal disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 1997;6:819–836. doi: 10.1517/13543784.6.7.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Von Korff MR, Feld AD. Intergenerational transmission of gastrointestinal illness behavior. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:451–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Levy RL, Langer SL, Whitehead WE. Social learning contributions to the etiology and treatment of functional abdominal pain and inflammatory bowel disease in children and adults. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2397–2403. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Whitehead WE, Busch CM, Heller BR, Costa PT. Social learning influences on menstrual symptoms and illness behavior. Health Psychol. 1986;5:13–23. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.5.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Lowman BC, Drossman DA, Cramer EM, McKee DC. Recollection of childhood events in adults with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;9:324–330. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198706000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatization symptoms in pediatric abdominal pain patients: relation to chronicity of abdominal pain and parent somatization. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1991;19:379–394. doi: 10.1007/BF00919084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Heizer WD, Southern S, McGovern S. The role of diet in symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a narrative review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1204–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Morcos A, Dinan T, Quigley EM. Irritable bowel syndrome: role of food in pathogenesis and management. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:237–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Austin GL, Dalton CB, Hu Y, Morris CB, Hankins J, Weinland SR, Westman EC, Yancy WS, Drossman DA. A very low-carbohydrate diet improves symptoms and quality of life in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:706–708.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Simrén M, Månsson A, Langkilde AM, Svedlund J, Abrahamsson H, Bengtsson U, Björnsson ES. Food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2001;63:108–115. doi: 10.1159/000051878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Nanda R, James R, Smith H, Dudley CR, Jewell DP. Food intolerance and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1989;30:1099–1104. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.8.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Jarrett M, Heitkemper MM, Bond EF, Georges J. Comparison of diet composition in women with and without functional bowel disorder. Gastroenterol Nurs. 1994;16:253–258. doi: 10.1097/00001610-199406000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Saito YA, Locke GR, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Diet and functional gastrointestinal disorders: a population-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2743–2748. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy: recent advances in pathophysiology and treatment. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:261–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042407.205711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Ostgaard H, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Diet and effects of diet management on quality of life and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Report. 2012;5:1382–1390. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Ford AC, Talley NJ, Spiegel BM, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Schiller L, Quigley EM, Moayyedi P. Effect of fibre, antispasmodics, and peppermint oil in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a2313. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Francis CY, Whorwell PJ. Bran and irritable bowel syndrome: time for reappraisal. Lancet. 1994;344:39–40. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Bijkerk CJ, de Wit NJ, Muris JW, Whorwell PJ, Knottnerus JA, Hoes AW. Soluble or insoluble fibre in irritable bowel syndrome in primary care? Randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b3154. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Kassinen A, Krogius-Kurikka L, Mäkivuokko H, Rinttilä T, Paulin L, Corander J, Malinen E, Apajalahti J, Palva A. The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjects. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:24–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Spiller R. Review article: probiotics and prebiotics in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:385–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Brenner DM, Moeller MJ, Chey WD, Schoenfeld PS. The utility of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1033–1049; quiz 1050. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Levy RL, Linde JA, Feld KA, Crowell MD, Jeffery RW. The association of gastrointestinal symptoms with weight, diet, and exercise in weight-loss program participants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:992–996. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00696-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Spiller RC. Role of infection in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42 Suppl 17:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1925-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Spiller R, Garsed K. Infection, inflammation, and the irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:844–849. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Spiller R, Garsed K. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1979–1988. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Neal KR, Hebden J, Spiller R. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms six months after bacterial gastroenteritis and risk factors for development of the irritable bowel syndrome: postal survey of patients. BMJ. 1997;314:779–782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7083.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Spiller RC, Jenkins D, Thornley JP, Hebden JM, Wright T, Skinner M, Neal KR. Increased rectal mucosal enteroendocrine cells, T lymphocytes, and increased gut permeability following acute Campylobacter enteritis and in post-dysenteric irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2000;47:804–811. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.6.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Spiller R. Serotonin, inflammation, and IBS: fitting the jigsaw together? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45 Suppl 2:S115–S119. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31812e66da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Khan WI, Ghia JE. Gut hormones: emerging role in immune activation and inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;161:19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Yang GB, Lackner AA. Proximity between 5-HT secreting enteroendocrine cells and lymphocytes in the gut mucosa of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) is suggestive of a role for enterochromaffin cell 5-HT in mucosal immunity. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;146:46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Qian BF. An experimental study on the interaction between the neuro-endocrine and immune systems in the gastrointestinal tract. In: Ume University Medical Dissertations., editor. Vol. 719. Umeå, Sweden: Arbetslivsinstitutets; 2001. pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 170.Isgar B, Harman M, Kaye MD, Whorwell PJ. Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in ulcerative colitis in remission. Gut. 1983;24:190–192. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.3.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Ansari R, Attari F, Razjouyan H, Etemadi A, Amjadi H, Merat S, Malekzadeh R. Ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome: relationships with quality of life. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:46–50. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f16a62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Simrén M, Axelsson J, Gillberg R, Abrahamsson H, Svedlund J, Björnsson ES. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBS-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Minderhoud IM, Oldenburg B, Wismeijer JA, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. IBS-like symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission; relationships with quality of life and coping behavior. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:469–474. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000020506.84248.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Keohane J, O’Mahony C, O’Mahony L, O’Mahony S, Quigley EM, Shanahan F. Irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a real association or reflection of occult inflammation? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1788, 1789–1794; quiz 1795. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.El-Salhy M, Lillebø E, Reinemo A, Salmelid L. Ghrelin in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Mol Med. 2009;23:703–707. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Sjölund K, Ekman R, Wierup N. Covariation of plasma ghrelin and motilin in irritable bowel syndrome. Peptides. 2010;31:1109–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–660. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Date Y, Kojima M, Hosoda H, Sawaguchi A, Mondal MS, Suganuma T, Matsukura S, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. Ghrelin, a novel growth hormone-releasing acylated peptide, is synthesized in a distinct endocrine cell type in the gastrointestinal tracts of rats and humans. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4255–4261. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.11.7757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Hataya Y, Akamizu T, Takaya K, Kanamoto N, Ariyasu H, Saijo M, Moriyama K, Shimatsu A, Kojima M, Kangawa K, et al. A low dose of ghrelin stimulates growth hormone (GH) release synergistically with GH-releasing hormone in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4552. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.8002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Wren AM, Seal LJ, Cohen MA, Brynes AE, Frost GS, Murphy KG, Dhillo WS, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Ghrelin enhances appetite and increases food intake in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5992. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Edholm T, Levin F, Hellström PM, Schmidt PT. Ghrelin stimulates motility in the small intestine of rats through intrinsic cholinergic neurons. Regul Pept. 2004;121:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Tebbe JJ, Mronga S, Tebbe CG, Ortmann E, Arnold R, Schäfer MK. Ghrelin-induced stimulation of colonic propulsion is dependent on hypothalamic neuropeptide Y1- and corticotrophin-releasing factor 1 receptor activation. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:570–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Hosoda H, Kojima M, Kangawa K. Ghrelin and the regulation of food intake and energy balance. Mol Interv. 2002;2:494–503. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.8.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Masuda Y, Tanaka T, Inomata N, Ohnuma N, Tanaka S, Itoh Z, Hosoda H, Kojima M, Kangawa K. Ghrelin stimulates gastric acid secretion and motility in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:905–908. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Fujino K, Inui A, Asakawa A, Kihara N, Fujimura M, Fujimiya M. Ghrelin induces fasted motor activity of the gastrointestinal tract in conscious fed rats. J Physiol. 2003;550:227–240. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]