SUMMARY

Idiopathic carotidynia or Fay syndrome is a little known pathology, which in the past was the subject of much controversy. Even though carotydinia was removed as a pathological entity from the second International Headache Society classification in 2004, recent reports seem to confirm that the disease demonstrates unusual radiological findings. The presence of a typical amorphous enhancing soft tissue surrounding the carotid artery by MRI, CT and ultrasonography in patients with carotidynia has reopened discussion on the hypothesis that carotidynia may represent a distinctive inflammatory process. The aetiology of carotidynia is unknown. We report a case of carotidynia that developed after an upper airway infection, wherein MR studies demonstrated typical enhanced tissue surrounding the common carotid artery in contiguity with pathological enhancement in laryngeal tissue.

KEY WORDS: Carotidynia, MRI, Doppler ultrasonography, Airways infection

RIASSUNTO

La carotidodinia idiopatica o sindrome di Fay è una patologia poco conosciuta ed in passato oggetto di molte controversie. Anche se il termine carotidodinia è stato rimosso come entità patologica dalla seconda classificazione delle emicranie della Società Internazionale di Emicrania del 2004, studi recenti sembrano confermare che questa malattia presenta aspetti radiologici del tutto peculiari. La presenza alla RM, TC ed ecografia di un tipico incremento del segnale a livello del tessuto molle circostante l'arteria carotide riapre la discussione sull'ipotesi che la carotidodinia possa rappresentare una distinta entità nosologia. L'eziologia della carotidodinia è ancora sconosciuta. Riportiamo un caso di carotidodinia insorta dopo un'infezione delle vie aeree superiori, nel quale lo studio RM dimostra il tipico tessuto che circonda l'arteria carotide comune in contiguità con un aumento patologico del segnale a livello del tessuto laringeo.

Introduction

Carotidynia or Fay syndrome was described by Fay 1 in 1927 as an atypical neuralgia in the neck and face. It was classified by the International Headache Society (HI S) in 1988 as an idiopathic neck pain syndrome associated with tenderness over the carotid bifurcation without structural abnormality 2. This entity was mainly previously acknowledged by neurologists as a variant of a migraine, and often treated accordingly with prophylactic medications 3. However, some authors believed carotidynia to be a clinicopathological entity, suggesting that it was merely a symptom of various and heterogeneous causes of neck pain 4. These controversial aspects led the Headache Classification Subcommittee of HI S to remove carotidynia as a distinct entity from the main classification in 2004 5.

Several recent publications have demonstrated that carotidynia not only represents a symptom, but probably a distinct pathological entity with structural abnormalities and characteristic radiological findings 6-10.

The presence of focal eccentric thickening of the carotid wall by enhancing tissue, generally without haemodynamic changes, is a typical pattern found in imaging studies in patients suffering from carotidynia. These findings have reopened discussion on the hypothesis that carotidynia is a distinct disease entity, possibly caused by inflammation of the carotid adventitia.

We report a case of carotidynia that developed after an upper airway infection where MR studies demonstrated the typical enhanced tissue surrounding the common carotid artery in contiguity with pathological enhancement in laryngeal tissue.

Case report

A 70-year-old male came under our observation complaining of localized cervical pain in the anterior-right area of the neck, aggravated by swallowing, coughing, headache and low-grade fever that was preceded by a flulike episode of an upper respiratory tract infection with dysphonia. The patient was treated by his general practitioner with oral amoxicillin-clavulanate for one week. The respiratory illness had also affected other members of his family. Clinical history included hypercholesterolaemia and a surgical procedure for a left posterior tibial artery thrombosis 10 years ago.

Physical examination revealed a right swelling and tenderness overlying the right carotid bifurcation, painful to the touch, while no associated-lymphadenopathy was noted. The remaining ENT examination was normal and endoscopy of the upper aerodigestive tract did not reveal any macroscopic signs of inflammation.

A neck abscess was suspected. The patient was therefore admitted and intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole was administered. A cervical CT scan performed on admission revealed the presence of abnormally enhanced inflammatory tissue surrounding the symptomatic right common carotid artery. No cervical lymphadenopathy was noted.

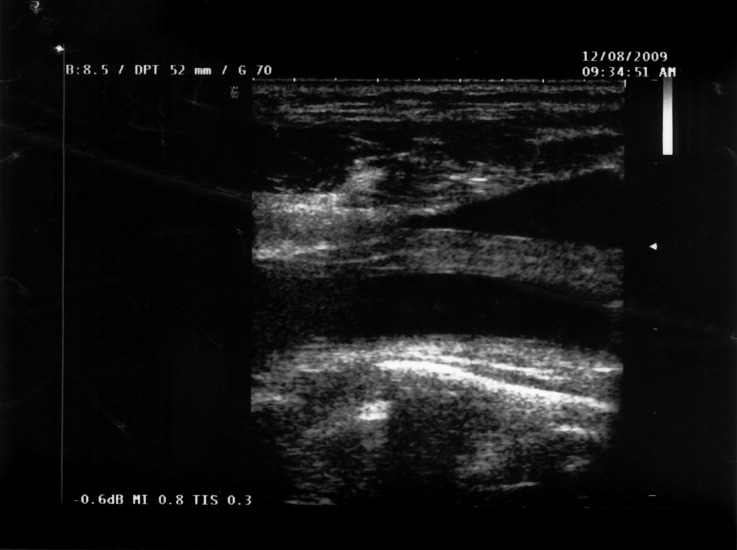

Laboratory findings demonstrated normal peripheral blood cell counts. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated at 101 mg/l, and erythrocyte sedimentation rapidity (ESR) was increased at 84 mm/h. Serum amyloid A (SAA) protein was also elevated to 467 mg/l (normal range < 10) and fibrin degradation product D-dimer was 866 mg/l (normal range < 225). Ultra-sonography of the carotid artery (Fig. 1) showed hypoechoic wall thickening of the right common artery with a slight narrowing of the vessel. The internal profiles of the vessel lumen were normal.

Fig. 1.

Ultrasonography of the carotid artery with hypoechoic wall thickening.

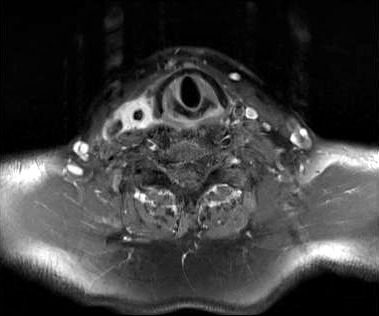

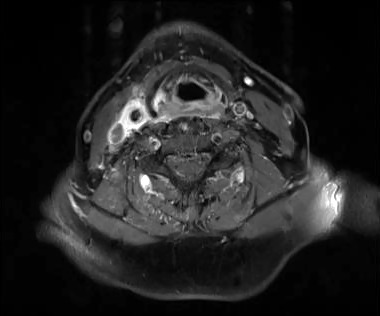

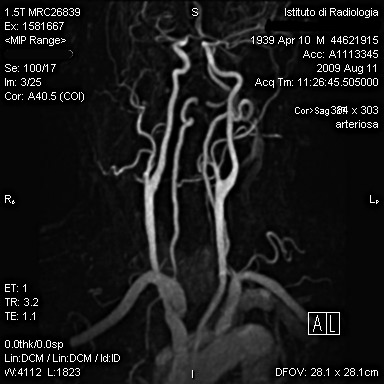

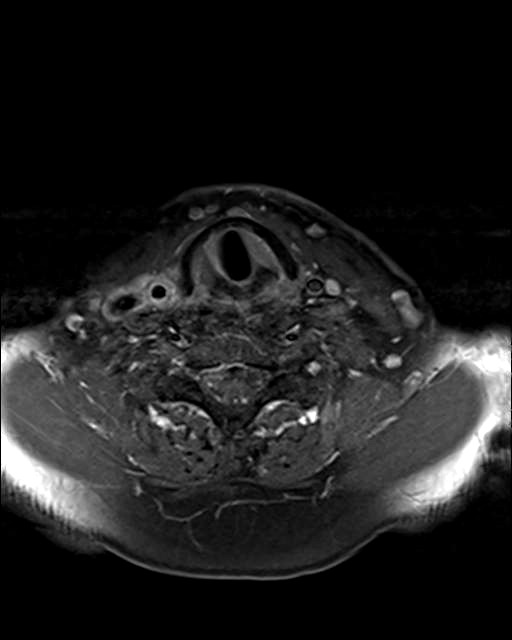

MRI of the neck in T1 weighted axial imaging revealed an abnormal gadolinium-enhancing tissue surrounding the right common carotid artery (Fig. 2). The enhanced tissue extended cranio-caudally in sagittal imaging (Fig. 3) for 7 cm, and laterally displaced the internal jugular vein. In axial projections, an abnormal, substantial, hypervascularized area was visible in the region of the piriform sinus apparently in contiguity with the involved carotid artery (Fig. 4). Angio-MRI confirmed the ultra-sonographic findings of the complete integrity of the vessel lumen (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

T1 weighted axial MRI imaging.

Fig. 3.

T1 weighted sagittal MRI imaging.

Fig. 4.

T1 weighted axial MRI imaging with abnormal hypervascularized area in the region of the piriform sinus.

Fig. 5.

Angio-MRI showing the complete integrity of the vessel lumen.

Serum IgM antibodies against cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr virus, Varicella Zoster virus, parotitis virus, Treponema pallidum, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Toxoplasma gondii and Histoplasma capsulatum were negative. Hepatitis B surface–antigen and hepatitis C virus-antibody tests were negative. Human immunodeficiency virus antibodies 1-2 were negative. Nasopharyngeal culture for adenovirus, influenza type A-B virus, para-influenza type 1-2-3 virus, respiratory syncytial virus and metapneumovirus was negative.

Diagnosis of Fay syndrome was finally confirmed and antibiotic therapy, which was unsuccessful in controlling pain and tenderness, was stopped. Intramuscular nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory therapy with ibuprofen 100 mg/ day was administered and after two weeks of treatment there was progressive, rapid improvement of symptoms. MRI performed after 10 days after revealed the reduction of the pericarotideal enhancing tissue (Fig. 6), and the pathological enhancement in the larynx had completely disappeared. CRP and SAA values, four weeks later, were within normal limits.

Fig. 6.

Follow-up MRI, 10 days after therapy.

Discussion

Syms et al. 11, in 1997, first described MR findings in a patient with carotidynia. The subject experienced abnormally enhanced tissue surrounding the symptomatic carotid artery. The same findings were confirmed by Burton et al. 6 in 2000, in a series of MR imaging of five patients with carotidynia. More recently, a published series of cases 7-10 defined some structural abnormalities demonstrated by different imaging techniques. MRI and angio- MRI allow detailed analysis of the typical pathological tissue surrounding the involved artery and clearly show the integrity of the vessel lumen. It was observed that the structural changes were limited to adventitia of the carotid artery 12. In the unique histological study of the abnormal perivascular tissue surrounding the carotid, Upton et al. 12 in 2003, demonstrated the presence of non-specific inflammatory changes including vascular proliferation, proliferation of fibroblasts and low-grade chronic active inflammation.

MRI also allows the exclusion of other pathological conditions of the artery, and in particular arterial dissection, intra-luminal haemorrhage, thrombosis and aneurysm. Duplex ultra-sonography confirms the absence of haemodynamic

changes in the lumen. A positron-emission tomography CT study of a series of patients suffering from carotidynia by Amaravadi et al. 13 revealed that the enhancing soft tissue around the carotid corresponds to a focus of glucose hypermetabolism. Glucose hypermetabolism, in absence of a cervical mass and with the self-limiting course of the disease, is further confirmation of the inflammatory nature of the lesion. The elevated value of CRP and SAA in the acute phase of carotidynia and their gradual decrease with the improvement of the disease observed in our case, are in agreement with the findings of Taniguchi et al. 14. Very recently, another marker of inflammation related to vasculitis has been noted to increase in carotidynia. It has been reported 15 that the level of serum soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1), a marker of activity of large-vessel vasculitis in giant cell arteritis and Kawasaki disease, is correlated, as well as CRP and SAA, with the clinical stage of carotidynia. These findings have led some authors to hypothesize that carotidynia is a subset of vasculitis. Our case confirms all the findings recently reported in literature, although it differs from previous reports in the MRI evidence of a pathological enhancement of the laryngeal tissue contiguous with the involved carotid artery. Figure 4 clearly shows that the enhancement involves the area of the right piriform sinus, arytenoid and reaches the carotid adventitia posteriorly to the thyroid cartilage to create a barrier for direct contact. These findings, together with the history of a preceding upper airways flu-like episode with dysphonia lead to the hypothesis that carotidynia may develop after an upper airway infection for contiguity. Laboratory tests for a possible viral agent was however unsuccessful.

A history of upper airway infection is not a common finding in patients suffering from carotidynia. Woo et al. 16 reported a case of carotidynia preceded by a flu-like illness with low-grade fever, chills, fatigue and myalgia, but without MRI evidence of involvement of the upper airways. They described a previously unreported finding, namely resolution of an intimal plaque noted on imaging at the time of initial presentation.

In conclusion, our case seems to demonstrate, as suggested by Tardy et al. 17, that the term carotidynia may be confusing and the term carotiditis is more appropriate. An increasing number of reports on carotidynia may produce new investigations on the infective aspects of this little known pathology.

References

- 1.Fay T. Atypical neuralgia. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1927;18:309–315. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society, author. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders,cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1988;8(Suppl 7):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray TJ. Carotidynia:a cause of neck and face pain. Can Med Assoc J. 1979;120:441–443. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biousse V, Bousser MG. The myth of carotidynia. Neurology. 1994;44:993–995. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society, author. The International Classification of Headache Disorders 2ndEdn. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(Suppl 1):9–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton BS, Syms MJ, Petermann GW, et al. MR imaging of patients with carotidynia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:766–769. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhn J, Harzheim A, Horz R, et al. MRI and ultrasonographic imaging of a patient with carotidynia. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:483–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kosaka N, Sagoh T, Uematsu H, et al. Imaging by multiple modalities of patients with carotidynia syndrome. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:2430–2433. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0550-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park JK, Choi JC, Kim BS, et al. CT imaging features of carotidynia: a case report. J Neuroimaging. 2009;19:84–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2007.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Da Rocha AJ, Tokura EH, Romualdo AP, et al. Imaging contribution for the diagnosis of carotidynia. J Headache Pain. 2009;10:125–127. doi: 10.1007/s10194-009-0099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Syms MJ, Burton BS, Burgess LPA. Magnetic resonance imaging in carotydinia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:156–159. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Upton PD, Walker Smith JG, Charnock DR. Histologic confirmation of carotidynia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:443–444. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59980300611-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amaravadi RR, Behr SC, Kousoubris PD, et al. §18F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography- CT imaging of carotidynia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1197–1199. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taniguchi Y, Horino T, Hashimoto K. Is carotidynia syndrome a subset of vasculitis? J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1901–1902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taniguchi Y, Horino T, Terada Y. The activity of carotidynia syndrome is correlated with the soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) level. South Med J. 2010;103:277–278. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181cf39e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo JKH, Jhamb A, Heran MKS, Hurley M, Graeb D. Resolution of existing intimal plaque in a patient with carotidynia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:732–733. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tardy J, Pariente J, Nasr N, et al. Carotidynia: a new case for an old controversy. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:704–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]