Abstract

Adenosine analogs, such as N6-cyclohexyladenosine (CHA) that are selective for A1-adenosine receptors, and analogs, such as 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA) that are active at both A1 and A2 receptors, cause a profound depression of locomotor activity in mice via a central mechanism. The depression is effectively reversed by non-selective adenosine antagonists such as theophylline. We report that 2-[(2-aminoethyl-amino)carbonylethylphenylethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (APEC), an amine derivative of the A2-selective agonist, CGS21680, is a potent locomotor depressant in mice. The in vivo pharmacology is consistent with A2-selectivity at a central site of action. Two parameters indicative of locomotor activity, horizontal activity and total distance travelled, were measured using a computerized activity monitor. From dose-response curves it was found that APEC (ED50 16 μg/kg) is more potent than CHA (ED50 60 μg/kg) and less potent than NECA (ED50 2 μg/kg). The locomotor depression by APEC was reversible by theophylline, but not by the A1-selective antagonists 8-cyclopentyltheophylline (CPT) and 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropyl-2-thioxanthine, nor by the peripheral antagonists 8-p-sulfophenyltheophylline (8-PST) and 1,3-dipropyl-8-p-sulfophenylxanthine. The locomotor activity depression elicited by NECA and CHA was reversed by A1-selective antagonists. These results suggest that the effects of APEC are due to stimulation of A2 adenosine receptors in the brain.

Keywords: Adenosine analog, Locomotor depression, Adenosine receptor

1. INTRODUCTION

Adenosine, as a neuromodulator, inhibits the firing of neurons and the release of neurotransmitters in the central nervous system [1]. In behavioral models, adenosine agonists, acting via a central mechanism, cause a dramatic depression of locomotor activity, which is effectively reversed by the non-selective adenosine antagonists, caffeine and theophylline [2]. This effect has been demonstrated in rodents using a number of potent adenosine analogs, including the non-selective agonist, N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA), and the A1 selective agonists, N6-cyclohexyl-and N6-cyclopentyladenosine [3–5]. The potencies in producing hypomobility, as measured by head dipping and locomotor assays, of a series of adenosine agonists were recently found to correlate to the potencies of the analogs at A2 receptors [6], suggesting that primarily A2 receptors are involved in these effects. The lack of a truly A2-selective agonist has hampered these studies.

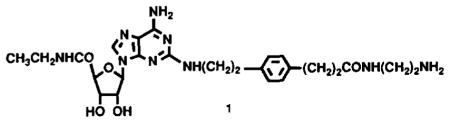

Recently, several classes of A2-selective adenosine agonists have been reported. N6-[2-(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-(2-methylphenyl)ethyl] adenosine [7] and 2-(carboxyethylphenylethylamino)adenosine-5′-carboxamide (CGS21680) [8,9] are A2-selective in competitive binding experiments at central A1- (measured in cortex) and A2- (measured in striatum) adenosine receptors by factors of 32 and 140, respectively. CGS21680 was also shown to be A2-selective in the cardiovascular system [9]. CGS21680 contains a carboxylic acid functionality, which is expected to limit its passage across the blood/brain barrier [9]. Using a functionalized congener approach, a series of long-chain derivatives of CGS21680 that retain A2 potency and selectivity and do not contain the carboxylic functionality, was synthesized [10]. An amine derivative, 2-[(2 -aminoethyl-amino)carbonylethylphenylethylamino]-5′-carboxamidoadenosine (APEC; 1), served as a synthetic intermediate for molecular probes for A2-adenosine receptors, including the first photo-affinity ligand, 125I-PAPA-APEC [11]. We report that APEC, which is 17-fold A2-selective in vitro [10], is a potent locomotor depressant in mice. The in vivo pharmacology is consistent with A2-selectivity at a central site of action.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Chemicals

NECA, CHA, 8-PST, CPT, DPSPX and XAC were obtained from Research Biochemicals, Inc. (Natick, MA). 2-Thio-CPX [13] was the generous gift of Professor W. Pfleiderer (Univ. of Konstanz, FRG and Dr J. Neumeyer, RBI). CGS 21680C (Na salt) was the generous gift of Dr A. Hutchison (CIBA-Geigy Corp.). APEC was synthesized as described [10].

2.2. Animal studies

2.2.1. Subjects

Adult male mice of the NIH (Swiss) strain weighing 25–30 g were housed in groups of 12 animals per cage with a light-dark cycle of 12:12 h. The animals were given free access to standard pellet food and water and were habituated for 24 h in laboratory conditions prior to testing. Each animal was used only once in the activity monitor.

2.2.2. Locomotor activity

Individual animals were studied in a Digiscan activity monitor (Omnitech Electronics Inc., Columbus, OH) equipped with an IBM-compatible computer. Data was collected in the morning, for 3 consecutive intervals of 10 min each and analyzed as a group for 30 min sampling period. Two non-equivalent parameters [15] were analyzed: (i) horizontal activity, which represents the total number of beam interruptions in the horizontal direction; and (ii) total distance travelled, which indicates the distance in cm travelled by the animal. The latter is dependent on the path taken.

2.2.3. Drug administration

All drugs were dissolved in a 1:4 v/v mixture of Emulphor EL-620 (GAF Chemicals Corp., Wayne, NJ) and phosphate-buffered saline and administered i.p. in a vol. of 5 ml/kg b. wt. Warming and sonication aided in dissolving the drugs. When appropriate, an adenosine antagonist was injected first followed by an agonist after 10 min. Immediately after the final injection, the mouse was placed in the activity monitor cage, and data collection was begun after a delay of 10 min. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t-test. Each value reported represents the mean ± SE for 6–10 animals, except for the control points (vehicle injected) for which n = 22.

3. RESULTS

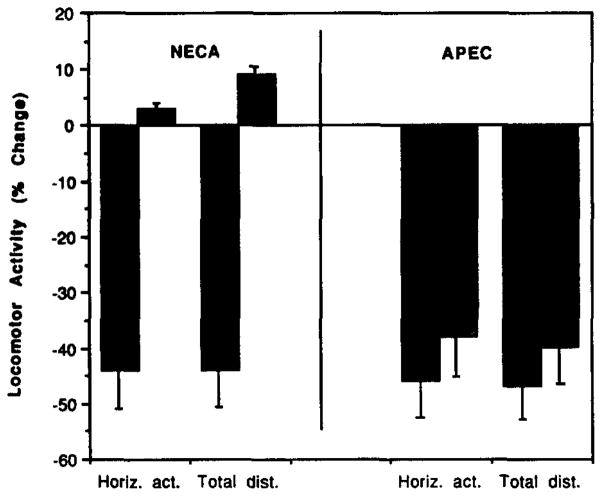

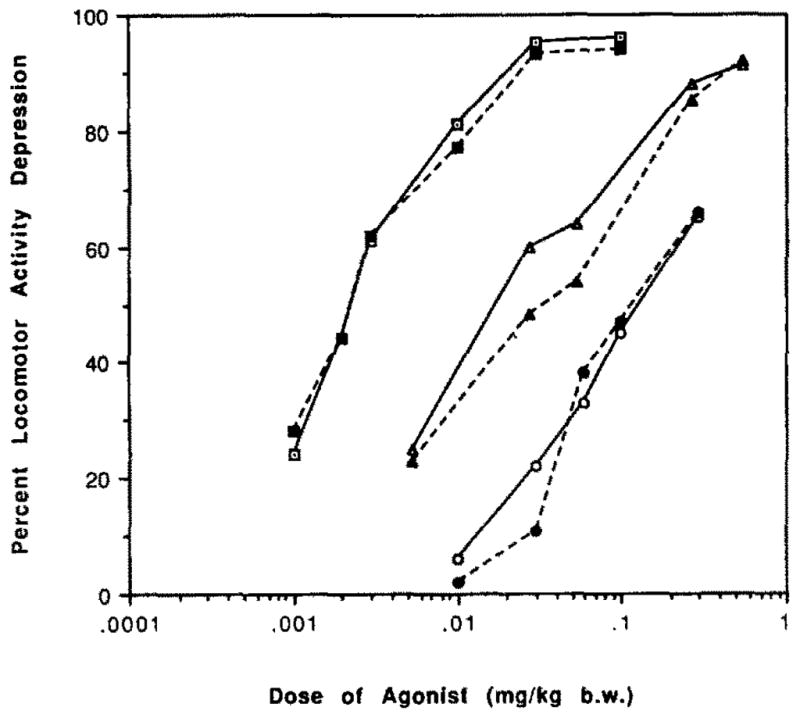

The locomotor effects at different doses of APEC and the adenosine agonists NECA and CHA, administered intraperitoneally in mice, were measured. The dose-response curves are given in fig. 1. APEC was found to have an ED50 value for horizontal activity of 14 μg/kg b. wt. Thus, APEC is more potent than CHA (ED50 = 70 μg/kg) and less potent than NECA (ED50 = 2 μg/kg). CGS21680 was also tested as a locomotor depressant at several doses. CGS21680 at a dose of 16 μg/kga was nearly inactive with 3 ± 0.2% and 13 ± 1% depression of horizontal activity (h.a.) and total distance travelled (t.d.), respectively. At a dose of 1 μmol/kg, CGS21680 caused decreases of 64 ± 4.5% (h.a.) and 62 ± 5% (t.d.) in locomotor activity, and at 3 μmol/kg the locomotor depression was 94 ± 9% (h.a.) and 96 ± 20% (t.d.).

Fig. 1.

Dose-response curves for locomotor depression in mice by the adenosine agonists, NECA (squares), APEC (triangles) and CHA (circles). For each analog, percent decrease compared to vehicle control is shown for horizontal activity (open symbols) and total distance (closed symbols).

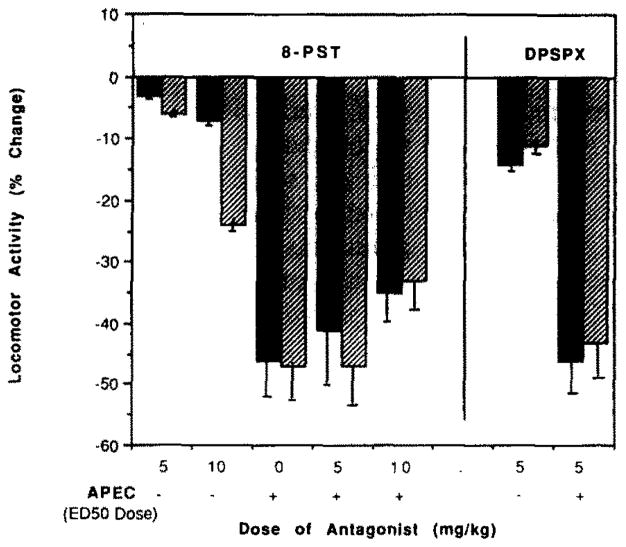

The locomotor depressant activity of APEC was not reversed by the peripheral adenosine antagonist, 8-p-sulfophenyltheophylline (8-PST; fig. 2). This is consistent with a central mechanism for the locomotor depression by APEC. Similarly, the more potent 1,3-dipropyl-8-(p-sulfophenyl)xanthine (DPSPX) at 5 mg/kg did not antagonize APEC (fig. 2). Since 8-PST and DPSPX are relatively non-selective, a peripheral action at either A1 or A2 subtypes is precluded as the mechanism for the locomotor depression by APEC. Curiously, at high doses, these peripheral antagonists both elicited some locomotor depression. This depression is particularly evident in the effect of 10 mg/kg 8-PST on total distance travelled (24 ± 2% decrease). At 5 mg/kg the depressant effect on total distance travelled was 6 ± 0.5% and 12 ± 1.8% for 8-PST and DPSPX, respectively. The A1-selective antagonist, 2-thioCPX (see below), depressed locomotor activity only at a dose of 10 mg/kg, with decreases of 23 ± 3% (h.a.) and 28 ± 3.6% (t.d.). The mechanisms underlying such depressant effects are unclear. At a dose of 10 mg/kg 8-(p-sulfophenyl)caffeine, which is structurally related to 8-PST but inactive or weakly active, respectively, as an adenosine antagonist at A1 and A2 receptors [16], stimulated locomotor activity slightly by 6 ± 0.2% (h.a.) and 12 ± 1.8% (t.d.).

Fig. 2.

The effects of the peripheral adenosine antagonists, 8-PST and DPSPX, on locomotor depression induced by APEC (16 μg/kg). Changes in horizontal activity (solid bars) and total distance travelled (hatched bars), relative to vehicle control, are shown.

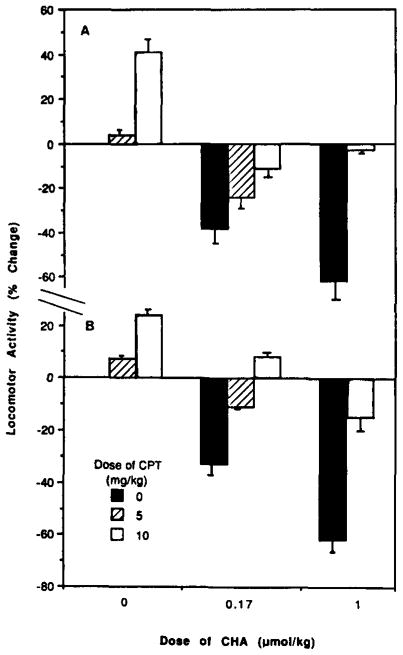

The A1-selective antagonist, 8-cyclopentyltheophylline (CPT), has been reported to antagonize the central depressant activities of adenosine agonists, such as N6-cyclopentyladenosine [4]. Similarly, we found that CPT could reverse the depression by an ED50 dose of CHA (fig. 3), an agonist that is A1-selective by a factor of 390 [12]. The depression evoked by an ED50 dose of NECA, an agonist that has marked activity at both adenosine receptor subtypes, was also completely reversed by this A1-selective antagonist (fig. 4). However, the locomotor depression evoked by APEC was not reversible by a comparable dose of CPT (fig. 4). This suggests that the depressant effect of APEC is due to stimulation of A2 adenosine receptors in the brain. The depressant effects of APEC were reversed by the non-selective antagonist theophylline. At the ED50 dose of APEC, 10 mg/kg theophylline restore the total distance travelled to 95 ± 12% of control.

Fig. 3.

The effects of the A1-selective adenosine antagonist, CPT, on locomotor depression induced by CHA (60 μg/kg). Percent changes in total distance travelled (A) and horizontal activity (B), relative to vehicle control, are shown.

Fig. 4.

The effects of an A1-selective antagonist on locomotor depression induced by adenosine 5′-carboxamide analogs. The percent change in locomotor activity, relative to vehicle control, induced by NECA (2 μg/kg) and APEC (16 μg/kg) at the ED50 doses, in the presence (hatched bars) and absence (solid bars) of 10 mg/kg CPT, is shown.

In contrast to PST, DPSPX and 2-thio-CPX at high doses, CPT alone at 10 mg/kg was found to be a weak central stimulant (fig. 3) causing increases of 41 ± 8% and 24 ± 7% for total distance travelled and horizontal activity, respectively. This finding is in contrast to a previous report [4] in which no stimulation by CPT (up to 30 mg/kg) was seen. To further study the effects of A1-selective adenosine antagonists on the locomotor depression by APEC, we searched for another centrally active A1-selective xanthine. The potent (Ki = 0.66 nM) and 480-fold A1-selective antagonist, 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropyl-2-thioxanthine (2-thio-CPX) [13,14], was shown to reverse the locomotor depression elicited by CHA (data not shown). At a dose of 5 mg/kg, 2-thio-CPX alone, unlike CPT, did not appreciably stimulate locomotor activity (increases of 1 ± 0.1% in both h.a. and t.d.). Like CPT, this xanthine failed to antagonize the locomotor effects of APEC, further supporting the conclusion of in vivo A2 selectivity of APEC. A combination of 5 mg/kg 2-thio-CPX and the ED50 dose of APEC depressed locomotor activity by 50 ± 10% (h.a.) and 55 ± 13% (t.d.).

4. DISCUSSION

The results show that APEC, previously determined to be A2-selective in binding assays at rat brain adenosine receptors [10], is a potent locomotor depressant in mice. The dose-response curves and the ED50 values for the effects of adenosine agonists on two parameters indicative of locomotor activity (horizontal activity and total distance travelled; fig. 1) show an order of potency of NECA > APEC > CHA. CHA (Ki 5 = 10 nM) is also less potent than NECA and APEC (Ki = 10.3 and 5.73 nM, respectively) in competitive binding experiments at A2 adenosine receptors [10,12]. The locomotor effects of APEC were not reversed by the A1-seleetive adenosine antagonists, CPT and 2-thio-CPX. Both of these xanthines are centrally active antagonists and both reverse the locomotor depression elicited by the A1 agonist, CHA. Moreover, the effect of the non-selective antagonist, theophylline, and the inactivity of peripheral, non-selective antagonists, PST and DPSPX, in reversing locomotor depression elicited by APEC suggests central action at adenosine receptors. The lack of antagonism of APEC-elicited depression by the A1-selective xanthines, CPT and 2-thio-CPX, strongly suggests that activation of A2 receptors are involved in the behavioral depression. Prior studies have suggested that activation of either A1 or A2 receptors can elicit dramatic depressant effects [2–6]. APEC now provides an important tool for investigation of the role of central A2 receptors, just as the A1-selective agonists, CHA and CPA, provide tools for investigation of the role of central A1 receptors.

CGS21680, the structural precursor of APEC, has been evaluated as a potentially therapeutic, hypotensive agent [9]. The charged carboxylate group is predicted to tend to restrict the action of this potent and highly selective A2 adenosine agonist (Ki = 14 nM) to the periphery [8]. It is possible that the reason for the behavioral inactivity of CGS21680 at a low dose, at which APEC is active, is due to diminished passage across the blood/brain barrier. At higher doses, CGS21680 acts as a locomotor activity depressant, but less potent than CHA, The aliphatic amino group of APEC is predominantly but not completely charged at physiological pH, which obviously does not prevent its entry into the CNS.

Yet to be resolved is why NECA is much more potent than APEC despite similar affinity at A2-receptors. In addition to pharmacokinetic factors, there remains the possibility that dual activation of A1 and A2 receptors by NECA is acting synergistically on locomotor depression. The blockade by CPT of NECA-elicited behavioral depression [4] suggests a key role for A1 receptors, yet other data [3] suggests that A2 receptors are involved. Preliminary results (unpublished) suggest that the effects of APEC and CHA are more than additive, supporting possible synergistic interactions of A1 and A2 receptors in eliciting behavioral depression.

Footnotes

The dose equal to the average of ED50 values for APEC for horizontal activity and total distance (corresponds to 0.03 μmol/kg APEC).

References

- 1.Snyder SH. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1985;8:103–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.08.030185.000535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snyder SH, Katims JJ, Annau Z, Bruns RF, Daly JW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:3260–3264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seale T, Abla KA, Shamim MT, Carney JM, Daly JW. Life Sci. 1988;43:1671–1684. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruns RF, Davis RE, Ninteman FW, Poschel BPH, Wiley JN, Heffner TG. In: Physiology and Pharmacology of Adenosine and Adenine Nucleotides. Paton DM, editor. Taylor and Francis; London: 1988. pp. 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heffner TG, Wiley JN, Williams AE, Bruns RF, Coughenour LL, Downs DA. Psychopharmacology. 1989;98:31–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00442002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durcan MJ, Morgan PF. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;168:285–290. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90789-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridges AJ, Bruns RF, Ortwine DF, Priebe SR, Szotek DL, Trivedi BK. J Med Chem. 1988;31:1282–1285. doi: 10.1021/jm00402a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutchison AJ, Williams M, DeJesus R, Oei HH, Ghai GR, Webb RL, Zoganas HC, Stone GA, Jarvis MF. J Med Chem. 1989 doi: 10.1021/jm00169a015. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutchison AJ, Webb RL, Oei HH, Ghai GR, Williams M. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1989;251:47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobson KA, Barrington WW, Pannell LK, Jarvis MF, Ji X-D, Hutchison AJ, Stiles GL. J Mol Recognition. 1990 doi: 10.1002/jmr.300020406. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrington WW, Jacobson KA, Williams M, Hutchison AJ, Stiles GL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6572–6576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruns RF, Lu GH, Pugsley TA. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;29:331–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson KA, Kiriasis L, Barone S, Bradbury BJ, Kammula U, Campagne JM, Secunda S, Daly JW, Pfleiderer W. J Med Chem. 1989;32:1873–1879. doi: 10.1021/jm00128a031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumeyer JL, De la Cruz D, Kiriasis L, Barone S, Bradbury BJ, Kammula U, Campagne JM, Secunda S, Daly JW, Pfleiderer W, Jacobson KA. Abstract B-16, Purine Nucleosides and Nucleotides in Cell Signalling: Targets for New Drugs (meeting); Sept. 1989.1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandberg PR, Hagenmeyer SH, Henault MA. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1985;7:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shamim MT, Ukena D, Padgett WL, Daly JW. J Med Chem. 1989;32:1231–1237. doi: 10.1021/jm00126a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]