Abstract

The purpose of this article is to summarize theoretical considerations in developing mortality risk models for people with spinal cord injury that are comparable to those in the general population, with an emphasis on behavioral and socioeconomic factors. The article describes the background and data that will ultimately be utilized to make these comparisons. This is part of a larger research initiative that addresses long-term outcomes after injury, including maintenance of health, quality of life, and longevity. This manuscript is a prelude to future analyses of data from this project.

Keywords: mortality risk, quality of life, spinal cord injury

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is associated with an elevated risk of mortality.1-8 Although the mortality rate during the first year after SCI onset has decreased steadily,2, 9 mortality among first-year survivors has not improved in recent years. This is of concern to rehabilitation professionals as there is a need to identify factors amenable to intervention.

A greater risk of mortality has been linked to several injury factors including a higher neurologic level, neurologic completeness of injury, and ventilator status.3,10 Violent etiology has also been associated with greater risk of mortality.2 Age is the primary demographic characteristic related to mortality, although gender and race have also been studied, with men having higher odds of mortality than women.11 Years since injury has not been consistently related to a differential risk of mortality,1,2 except that the risk of mortality is actually greater within the first year after onset2 and within the first 3 years for those who are ventilator dependent.10

Theoretical Risk Model

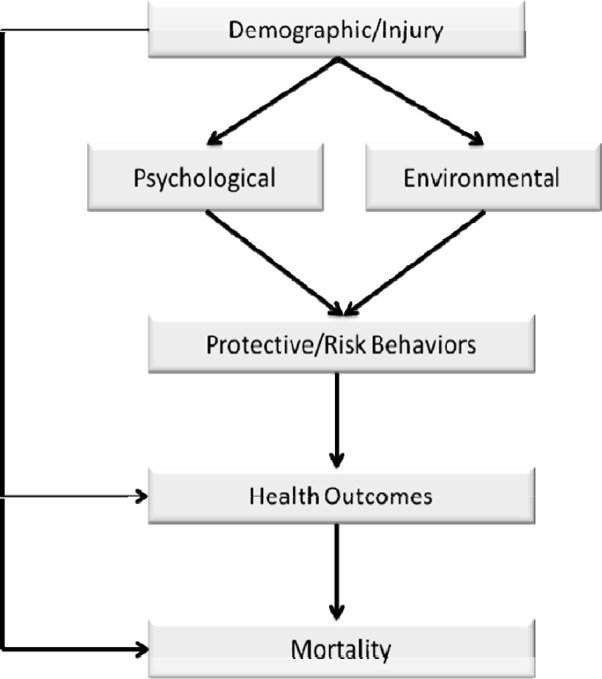

In 1996, we proposed a theoretical risk model (TRM; Figure 1) that groups predictive factors into 4 levels according to type and proximity to mortality.12 These factors include (a) demographic and injury characteristics, (b) psychological and environmental factors, (c) health behaviors, and (d) health status. With the exception of demographic and injury characteristics, which comprise the most basic level in the model and serve as statistical controls, the TRM is described by a series of mediational relationships whereby more distal factors are mediated by those more proximal to mortality. Health status variables are the most proximal to mortality, followed by health behaviors and psychological-environmental factors. For instance, the relationship of health behaviors with mortality is mediated by health status variables. Similarly, the relationship of psychological and environmental factors with health is mediated by health behaviors.

Figure 1.

Theoretical risk model.

Several studies have demonstrated the importance of each set of predictors after controlling for demographic and injury characteristics. In a study of health factors, risk of mortality was related to days hospitalized, infectious symptoms, fracture or amputation, surgeries to repair pressure ulcers, and probable major depression.13 In the behavioral analysis, a greater risk of mortality was associated with binge drinking, fewer hours out of bed, smoking, and prescription medication use to treat pain, spasticity, depression, and sleep problems.14 In the third analysis (psychological factors), 2 personality scales (sensation seeking, neuroticism-anxiety) were associated with a greater risk of mortality, whereas purpose in life was protective of mortality.15 Finally, among the environmental factors, low income and low social support increased risk of mortality.16 Economics was also significant in 2 distinct studies using SCI Model Systems (SCIMS) data.1,3

When simultaneously analyzing the full model, there were 10 significant predictors of mortality.17 These included 4 health factors (days hospitalized, fracture/amputation, pressure ulcer surgeries, probable major depression), 2 behaviors (psychotropic prescription medication use, binge drinking), income, age, injury severity, and years post injury. These findings support the overall sequencing or relative importance of factors within the model. However, mediation was not complete in that the 2 behaviors and income remained significant after inclusion of health factors.

Conceptual and Research Models Within the General Population 03

Research within the general population has laid the foundation for both comparison and interpretation with findings observed among people with SCI. However, such studies have not previously been linked within a common framework. One potential link relates to socioeconomic position that includes income, education, and wealth. Socioeconomic position has been consistently related to risk of mortality in the general population.18-21

There are differing perspectives regarding the mechanisms by which these factors affect mortality. Whereas one perspective is that socioeconomic position is confounded with other factors such as health behaviors (eg, individuals with lower socioeconomic status have more risk behaviors that, in turn, lead to mortality),22 a different approach considers socioeconomic position as a “fundamental cause” of differences in health and longevity.19, 23,24 According to this approach, interpersonal and contextual resources are associated with socioeconomic position such that those of higher socioeconomic position have greater longevity. These resources allow the individual to avoid health risks.

Lantz et al19 used a 3-stage model to identify the relationship of socioeconomic factors with mortality, controlling for other confounding factors. This required inclusion of multiple sets of risk factors within the same study. Demographic and socioeconomic status characteristics (education and income) were entered in the first stage. Behavioral factors were then added (stage 2), including smoking, drinking, body mass index, and physical activity. In the final stage, they entered health status and disability status (classified as none, some, moderate/severe). They found that low income (<$10,000 per year) was a risk factor for mortality even after accounting for health status, disability, and alcohol and smoking behaviors (each of which remained statistically significant in the final model). Education was no longer statistically significant. Previous research has suggested education is more highly associated with the development of the condition, whereas income is related to the course or severity of the condition once it occurs.25,26

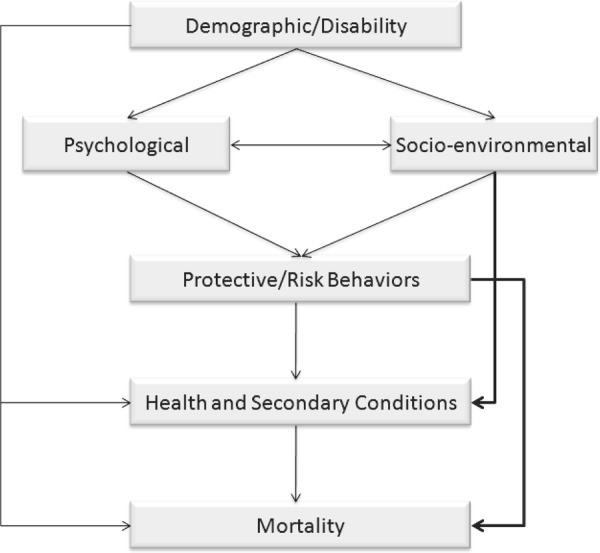

Enhanced Theoretical Risk Model

Figure 2 summarizes the TRM with the following 4 enhancements consistent with research findings and conceptual work within the general population: (a) replace injury factors with disability factors; (b) change environmental to socioenvironmental to specifically acknowledge socioeconomic factors; (c) add a direct path from socioenvironmental factors to health outcomes, acknowledging unknown predictive factors consistent with the “fundamental cause” hypothesis; and (d) add a direct path from behaviors to mortality to account for deaths related to intentional injuries and homicide. A previous elaboration was specifically directed at the role of income in relation to health and mortality, including the importance of both tangible and intangible benefits of higher income.11

Figure 2.

Modified theoretical risk model.

Future Data Analytic Strategies

We have implemented a 3-stage longitudinal study to identify predictors of mortality utilizing the TRM. Table 1 summarizes the dates of the studies and the number of participants. Stage 1 was initiated in 1997-1998 with the enrollment of a cross-sectional cohort of 1,386 participants, all of whom had traumatic SCI, were adults (minimum 18 years of age), and were at least 1 year post injury. These data have been used in multiple studies of risk factors for mortality.13-17 Preliminary analyses using these data have suggested that population-based models generally apply after SCI. 03 Page 14 of 15

Table 1.

Number of study participants by study stage and cohort

| Cohort | |||||

| Years | 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | |

| 1997–1998 | 1,386 | 1,386 | |||

| 2007–2010 | 877 | 1,736 | 2,613 | ||

| 2011–2015 | 613a | 1,215a | 958a | 2,804a | |

Projected.

At the time of the second stage of data collection (2007-2010), there were 309 deceased cases among the 1,386 participants from 1997-1998. Of the remaining 1,077 participants, 877 returned usable materials. A second cohort was added during the second stage. There were 1,736 new participants, making a total of 2,613 responses during the second stage of the study. When considering the combined cohort, including those who responded only during the first stage, there were a total of 3,122 unique participants.

The third stage is just beginning. It includes a follow-up of both cohorts utilized in the first 2 studies, using an expanded assessment tool to better encompass components of the TRM. We are adding a projected 958 new participants from a population-based registry (grant number H133B090005). We have intentionally developed a strong core instrument so the data may be pooled with that of the first 2 cohorts to better assess risk of mortality.

The combination of all cohorts will result in an excess of 4,000 unique participants to be used in assessing risk of future mortality. The pooled data represent the largest set of available data on SCI with the diversity of variables required to fully incorporate and test the TRM in the evaluation of mortality after SCI. Although the number of participants pales in comparison to the SCIMS, the breadth of predictor variables greatly exceeds that of the SCIMS and will present unique opportunities for identification of risk of mortality and the establishment of prevention strategies based on these findings.

Summary

We have learned a great deal about risk of mortality after SCI at least partially through the development of the TRM. There are several comparable findings between studies of SCI and those of the general population, laying a foundation for an integrated framework of research. Particular attention needs to be given to socioenvironmental factors and behavioral factors, similar to that used in epidemiologic research in the general population. We now have 2 significant cohorts of SCI participants with diverse data to use to further the process of identifying those risk factors that may become the focus of intervention strategies to promote longevity after SCI, with a third cohort to be assessed in the near future. Our future research will utilize these data to refine the TRM, quantify the importance of various risk factors, and to more firmly establish the study of mortality after SCI by virtue of using integrated models with that of the general population.

Acknowledgments

The contents of this publication were developed under grants from the US Department of Education, NIDRR grant numbers H133N50022, H133B090005, and H133G050165, and was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health grant 1R01NS48117. However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and endorsement by the Federal Government should not be assumed.

References

- 1.Krause JS, Saunders LL, DeVivo M. Income and risk of mortality after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92 (3): 339–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeVivo MJ, Krause JS, Lammertse DP. Recent trends in mortality and causes of death among persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80 (11): 1411–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krause JS, DeVivo MJ, Jackson AB. Health status, community integration, and economic risk factors for mortality after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85: 1764–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lidal I, Snekkevik H, Aamodt G, Hjeltnes N, Biering-Sorensen F, Stanghelle J. Mortality after spinal cord injury in Norway. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39 (2): 145–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garshick E, Kelley A, Cohen SA, et al. A prospective assessment of mortality in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2005;43 (7): 408–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soden RJ, Walsh J, Middleton JW, Craven ML, Rutkowski SB, Yeo JD. Causes of death after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2000;38 (10): 604–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeo JD, Walsh J, Rutkowski SB, Soden RJ, Craven M, Middleton J. Mortality following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1998;36: 329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frankel HL, Coll JR, Charlifue SW, et al. Long-term survival in spinal cord injury: a fifty year investigation. Spinal Cord. 1998;36 (4): 266–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strauss DJ, DeVivo MJ, Paculdo DR, Shavelle RM. Trends in life expectancy after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87: 1079–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shavelle RM, DeVivo MJ, Strauss DJ, Paculdo DR, Lammertse DP, Day SM. Long-term survival of persons ventilator dependent after spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29 (5): 511–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krause JS, Saunders LL. Life expectancy estimates in the life care plan: accounting for economic factors. J Life Care Planning. 2010;9 (2): 15–28 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause JS. Secondary conditions and spinal cord injury: a model for prediction and prevention. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 1996;2 (2): 217–227 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krause JS, Carter RE, Pickelsimer E, Wilson D. A prospective study of health and risk of mortality after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89: 1482–1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause JS, Carter RE, Pickelsimer E. Behavioral risk factors of mortality after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(1):95–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krause JS, Carter R, Zhai Y, Reed K. Psychologic factors and risk of mortality after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90 (4): 628–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krause JS, Carter RE. Risk of mortality after spinal cord injury: relationship with social support, education, and income. Spinal Cord. 2009;47 (8): 592–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krause JS, Zhai Y, Saunders LL, Carter RE. Risk of mortality after spinal cord injury: an 8-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90 (10): 1708–1715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feinglass J, Lin S, Thompson J, et al. Baseline health, socioeconomic status, and 10-year mortality among older middle-aged Americans: findings from the health and retirement study, 1992-2002. J Gerontol: Soc Sci. 2007;62B (4): S209–S217 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lantz PM, Golberstein E, House JS, Morenoff J. Socioeconomic and behavioral risk factors for mortality in a national 19-year prospective study of U.S. adults. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70: 1558–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Widening socioeconomic inequalities in US life expectancy, 1980-2000. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35 (4): 969–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin CC, Rogot E, Johnson NJ, Sorlie PD, Arias E. A further study of life expectancy by socioeconomic factors in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13 (2): 240–247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.House JS, Kessler RC, Herzog AR.Age, socioeconomic status, and health. Milbank Q. 1990;68 (3): 383–411 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;extra issue:80–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Affairs. 2002;21 (2): 60–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmer Z, House JS. Education, income, and functional limitation transitions among American adults: contrasting onset and progression. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32: 1089–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herd P, Goesling B, House JS. Socioeconomic position and health: the differential effects of education versus income on the onset versus progression of health problems. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48 (3): 223–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]