Abstract

There is a renewed focus on targeted therapy against epigenetic events that are altered during the pathogenesis of lung cancer. However, the use of epigenomic modifiers as monotherapy lacks efficacy; thus, there is a need to develop safe and effective drug combinatorial regimens, which reverse epigenetic modifications and exhibit profound anticancer activity. Based on these perspectives, we evaluated, for the first time, the efficacy and associated mechanisms of a novel combinatorial regimen of histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi)—trichostatin A (TSA) and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA)—with silibinin (a flavonolignan with established pre-clinical anti-lung cancer efficacy) against non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Silibinin inhibited HDAC activity and decreased HDAC1–3 levels in NSCLC cells, leading to an overall increase in global histone acetylation states of histones H3 and H4. Combinations of HDCAi with silibinin synergistically augmented the cytotoxic effects of these single agents, which was associated with a dramatic increase in p21 (Cdkn1a). Subsequent ChIP assay indicated increased acetylated histone H3 and H4 levels on p21 promoter region, resulting in its increased transcription. The enhanced p21 levels promoted proteasomal degradation of cyclin B1, the limited supply of which halts the progression of cells into mitosis. Indeed, the resultant biological effect was a significant G2/M arrest by the combination treatment, followed by apoptotic cell death. Similar epigenetic modulations were observed in vivo, together with a marked reduction in xenograft growth. These findings are both novel and highly significant in establishing that HDACi with silibinin would be safe and effective to suppress NSCLC growth.

Keywords: silibinin, epigenetics, HDAC inhibitors, cell cycle, lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality around the world.1 It is classified as small cell lung cancer (SCLC) or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC); notably, approximately 75% of lung cancers are NSCLC and present a strong causal association with smoking.2 The high incidence and associated mortality of lung cancer have triggered a renewed focus on the study of targeted therapies against epigenetic events that become altered during the pathogenesis of this malignancy.2-5

Epigenetic events are heritable, yet reversible, dynamic changes in the genome that can occur in response to the environment, diet, disease and aging; they manifest in the form of DNA methylation, modifications of histone tails and non-coding RNAs.5-8 Among these epigenetic events, the silencing of tumor suppressor genes is associated with aberrant histone acetylation states.5,8-11 While histone acetylation by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) is associated with transcriptional activation, histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove acetyl groups on histone tails, resulting in a more compact chromatin configuration that restricts transcription factor access to DNA and represses gene expression.5,10 Thus, HDAC inhibitors (HDACi), due to their ability to reactivate epigenetically silenced genes that are essential for abrogating cancer cell survival and proliferation, are gaining interest as potential anticancer drugs.5,12,13

HDACi are categorized into short chain fatty acids, hydroxamic acids, cyclic tetrapeptides and benzamides5 and have shown therapeutic potential in pre-clinical studies, but have mostly failed as monotherapies against solid tumors in clinical settings5,13,14 [with the exception of hematological malignancies, for which a synthetic HDACi, vorinostat (a.k.a., suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, SAHA), has been approved for the treatment of relapsed and refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma5,13-16]. This clinical limitation of HDACi (showing nonequivalent responses in patients) has been attributed to solid tumor heterogeneity and differential effects of HDACi on different cell types.13,15-17 Considering this, it is now appreciated that the full therapeutic potential of HDACi can be best achieved in combination with other anticancer agents.12,13,18 Based on this notion, various studies are investigating the possible combination of HDACi with a vast array of cancer therapies.5,12,13,18 However, the major limitation of these studies is that the preconceived rationales for these combinations are not clearly defined; in addition, the molecular events governing the observed additive or synergistic effects are not clear, thereby yielding no useful information so as to direct their future clinical use.13

In the present study, we designed a strategy to effectively target NSCLC in vitro and in vivo, by a combinatorial regimen of Trichostatin A (TSA, a naturally occurring hydroxamic acid HDACi) or its synthetic analog, SAHA,5 with silibinin, a natural flavonolignan, which has shown promising anticancer potential against lung tumorigenesis.19-25 Both TSA and SAHA bind to the inside of HDAC catalytic site and inhibit deacetylase activity.5 While silibinin is known for its pleiotropic biological effects in lung tumorigenesis, its epigenetic effects are unknown.

Results

Silibinin causes inhibition of HDAC activity in NSCLC cells

First, we assessed whether silibinin modulates cellular HDAC activity. For this, H1299 cells were treated with silibinin (75–100 μM), and whole cell extracts were assayed for HDAC activity (Fig. 1A). Dose- and time-dependent inhibitory effects of silibinin were observed on HDAC activity, indicating that it has the potential to modulate HDAC activity under these conditions. Comparing silibinin and TSA (positive inhibitor) indicated that TSA is more potent initially, with strong HDAC activity inhibition, but later on displays a cyclic inhibitory pattern. Silibinin is less potent initially, but later exerts a more sustained inhibition. In the same lysates, we observed that silibinin caused a dose-dependent decrease in HDAC1–3 protein levels, suggesting that its inhibitory effect on HDAC activity may be due to decreased HDAC protein levels (Fig. 1B). To address this possibility, equal pull-downs of HDAC1–3 protein from similar silibinin-treated H1299 cells were analyzed for HDAC activity (Fig. 1C). Results showed that in spite of equal HDAC1–3 protein level in the pull-downs, there was a strong decrease in HDAC activity in silibinin-treated vs. vehicle control samples. This suggests that, indeed, silibinin inhibits HDAC activity in a cellular system at pharmacologically achievable concentrations (75–100 μM) in humans, and that this decrease in HDAC activity was independent of silibinin being able to decrease total HDAC1–3 protein levels.

Figure 1. Effect of silibinin on (A) HDAC activity in intact H1299 cells, (B) HDAC1–3 protein levels in H1299, H358 and H322 cells, (C) HDAC activity of equal pull-downs of HDAC1–3 proteins from treated H1299 cells and (D) Ac-H3 and Ac-H4 levels in H1299 cells and H358 cells. TSA (0.05–0.5 µM) was used as a positive control in HDAC activity assays. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 3. #p < 0.05; *p < 0.001

Silibinin causes accumulation of global acetylated histone H3 and H4 in cellular chromatin

HDAC inhibition directly influences downstream substrates, including post-transcriptional alterations of histones, causing the modifications in gene expression.5,10 To assess whether silibinin-mediated HDAC inhibition increased histone acetylation, levels of acetylated histone H3 (Ac-H3) and Ac-H4 were analyzed from similar silibinin-treated H1299 cells. As shown in Figure 1D, by 24 h silibinin treatment induced an increase in Ac-H3 levels (~2-fold), which later decreased to basal levels by 48 h. Similarly, Ac-H4 levels also increased (~3-fold) by 24 h and, after that time, even though the increase in Ac-H4 level was lower, it was still higher than basal level and remained sustained until 72 h after treatment. In additional studies, silibinin also strongly decreased HDAC1, 2 and 3 protein levels, in addition to inducing histone acetylation in other human NSCLC cell lines, H358 and H322 (Fig. 1B and D). Together, these results suggested that inhibition of HDAC activity and a decrease in HDAC expression are responsible for the accumulation of Ac-H3 and Ac-H4 after silibinin treatment in H1299 cells, and that this effect in NSCLC cells is not cell line specific.

HDACi in combination with silibinin increases apoptosis in H1299 cells

Next, we determined whether a novel combinatorial regimen of established HDACi with silibinin could have an enhanced cytotoxic effect on NSCLC cells. Accordingly, TSA, SAHA and silibinin effects were assessed alone and in combination on cell death and proliferation of H1299 cells (Fig. 2 and 3). MTT screening assay and combination index (CI) analysis, based on Chou-Talalay method26 employing CompuSyn software program, revealed (Fig. 2A; Table S1) that the drug interactions were strongly synergistic in SAHA + silibinin combinations (CI = 0.1–0.3), and very strongly synergistic in TSA + silibinin combinations (CI < 0.1). This also assisted us in dose selection, where combinatorial regimens for 24–72 h strongly increased cell death (Fig. S1A). The nature of cell death was confirmed as apoptotic: ~4–20-fold increase in apoptotic cells when using TSA + silibinin and ~3–10-fold increase when using SAHA + silibinin (p < 0.001) as compared with ~1–3, ~3–7 and ~3–5-fold increase when using either silibinin, TSA or SAHA alone, respectively (Fig. 2B). Simultaneous cleavage of caspase-9 and -3 and PARP further supported these observations (Fig. 2C). Both combinations also caused a robust decrease in the expression of anti-apoptotic molecules such as Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, survinin and XIAP (Fig. 2C), indicating their possible involvement in strong apoptotic cell death by combinatorial regimens compared with each agent alone. Furthermore, the combinatorial regimens strongly decreased total cell number [61–91% and 41–77% (p < 0.001) by TSA + silibinin and SAHA + silibinin combinations, respectively], indicating that they also significantly affect cellular proliferation (Fig. 3A).

Figure 2. Effect of TSA, SAHA and silibinin alone and in combination on (A) combination index, as determined by 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT)-viability assays (using non-constant combination ratios) after 72h of drug exposure (strong to very strong synergistic effects of the combinations was indicated by Fa-CI plots. Fa represents the fraction of cells that is growth-inhibited in response to drug treatments, and is calculated as 1-fraction of surviving cells), (B) % apoptotic cells analyzed by Annexin-V/ PI staining and (C) expression levels of proteins associated with apoptosis in H1299 cells. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 3. #p < 0.05, *p < 0.001.

Figure 3. Effect of TSA, SAHA and silibinin alone and in combination on (A) total cell number in H1299 cells, (B) cell cycle progression in H1299 cells, (C) left panel: IF staining for p-histone H3 Ser 10 and p-MPM-2 Ser /Thr positive cells and α-tubulin for mitotic spindle and DAPI as nuclear stain in H1299 cells, (C) right panel: % positive p-histone H3 Ser 10 mitotic cells and expression of p-MPM-2 Ser /Thr protein levels in H1299 cells and (D) protein expression levels of G2/M regulatory proteins in H1299 cells. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 3. #p < 0.05, *p < 0.001.

HDACi in combination with silibinin induces G2/M arrest of H1299 cells

Cell cycle progression and programmed cell death are two intricately linked processes, known to govern cell fate toward proliferation and survival.27 To examine the effects of combinatorial regimen on cell cycle progression, NSCLC H1299 cells were treated with single agents alone or combination and analyzed for cell cycle kinetics from 24–72h (Fig. 3B; Fig. S1B). Cells treated with silibinin or SAHA alone prominently arrested in G1 phase at all-time points; however, those treated with TSA showed G2/M arrest early followed by S phase arrest at later time-points. Conversely, combination treatments showed a gradual but significant increase in G2/M arrest in all cases (56–60%; p < 0.001). To identify whether these G2/M fractions of cells were arrested at G2 phase or undergoing a mitotic arrest, we analyzed 48 h treated cells for the expression of two mitotic markers, p-histone H3 Ser 10 and p-MPM-2Ser /Thr (Fig. 3C). As indicated by decreased nuclear expression of p-histone H3 Ser 10 (Fig. 3C, right panel), quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence (IF) data showed a significant decrease in mitotic index (% of cells in mitotic phase) by combinatorial treatments. This was further corroborated by decreased expression of MPM-2 reactive structured components of the mitotic apparatus (Fig. 3C, right panel) that are required for both onset and completion of M-phase.28 Overall, these studies suggested that relative to controls and single agents, combination treatment arrested the cells in G2 and not the M phase. Interestingly, since mitosis activated cell signaling is closely interconnected with the regulation of the microtubule cytoskeleton,29 the combinatorial treatment also affected the structural stability of α-tubulin (Fig. 3C), which is required for spindle formation,30 indicating that whereas co-treatments defer most of the cells from entering mitosis, the few cells that escape the G2 checkpoint do not undergo normal mitosis as a consequence of a disrupted tubulin network.

HDACi in combination with silibinin limits cyclin B1 availability by strongly inducing p21 Levels

The entry into mitosis involves activation of Cdc2 by its binding to cyclin B1 and phosphorylation at Thr-161.27 However, this Cdc2-cyclin B1 complex is maintained in an inactive state until the end of the G2 phase due to the phosphorylation of Cdc2 at Thr-14 and Tyr-15 sites. A rapid dephosphorylation of Cdc2 at these sites by phosphatase Cdc25C activates the Cdc2-cyclin B1 kinase complex, which translocates to the nucleus and results in entry into mitosis.27 To further understand the mechanism of cell cycle arrest by combinatorial treatments, G2/M regulatory molecules were next analyzed (Fig. 3D). Silibinin and SAHA alone decreased p-Cdc2Tyr-15 levels; however, both combination treatments almost completely abolished this inhibitory phosphorylation state of Cdc2, suggesting that cells were in fact transgressing from G2 into the M phase (Fig. 3D). Surprisingly, co-treatments also decreased total Cdc2 protein levels. Furthermore, cyclin B1 levels were also reduced by both single agents alone and by the combination treatments, the later causing a more dramatic effect in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 3D). Since in rapidly dividing cells cyclin B1 levels increase at the onset of G2/M phase, further rising during the metaphase-anaphase phases and declining as cells exit mitosis,31 it was evident that the decreased levels of cyclin B1 could be a major limiting factor restricting the cells from entering the M phase and resulting in strong arrest of cells in late G2 phase by combination treatments.

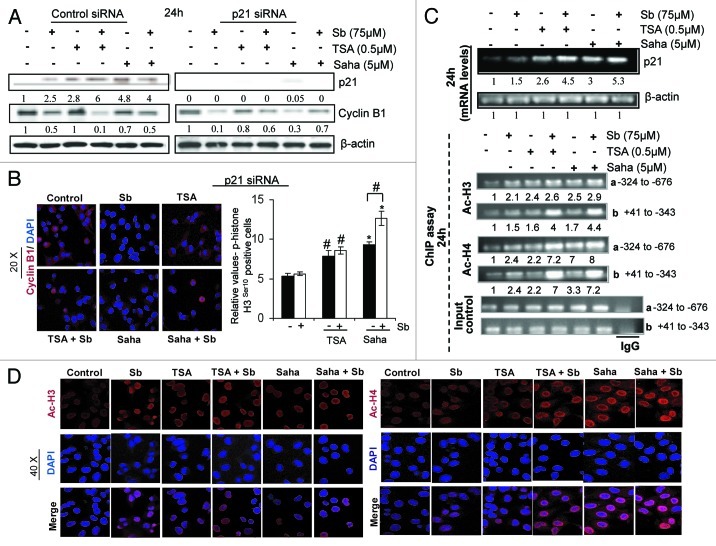

Parallel to the above observations, a dramatic increase in p21 (Cdkn1a) protein levels was also observed in co-treatments compared with single agents alone (Fig. 3D). In cancer cells, p21 binds and inactivates cyclin/Cdk complexes primarily mediating a G1 arrest,32 but recent studies have also suggested a role in inducing G2 arrest, either by interfering with the phosphorylation at Tyr 161 of Cdc2-cyclin B1 complex or by limiting the supply of cyclin B1 by causing its proteasomal degradation.33,34 Since p21 increase correlated with a decrease in cyclin B1 levels by combination treatments (Fig. 3D), we next examined whether p21 controlled cyclin B1 expression in our system by using siRNA for p21 in H1299 cells (Fig. 4A). Knocking down of p21 expression by siRNA did efficiently result in the emergence of cyclin B1 expression, as observed by immunoblotting (Fig. 4A) and IF staining for cyclin B1 (Fig. 4B) by 24h in combination treatments (Fig. 4A and B), whereas control siRNA did not. Stained cells were also analyzed for the presence of p-histone H3 Ser 10 in the nucleus (Fig. 4B, right panel); p21 knockdown cells exposed to the combination treatment showed a relative increase in mitotic cells compared with their respective controls, indicating that cyclin B1 was indeed available after p21 disappearance for entry into mitosis, though the defects in mitotic spindle were still evident (data not shown).

Figure 4. Effect of TSA, SAHA and silibinin alone and in combination on (A and B) left panel: cyclin B1 levels, (B) mitotic index in presence of silenced p21 (p21 siRNA) in H1299 cells, (C) top panel: p21 mRNA levels in H1299 cells, bottom panel: Ac-H3 and Ac-H4 levels on p21 promoter regions ‘a’ and ‘b’ of H1299 cells as detected by RT-PCR following ChIP assays and (D) IF staining for Ac-H3 and Ac-H4 levels in H1299 cells.

Interestingly, a decrease in cyclin B1 levels by silibinin alone seemed to be partly independent of p21, as indicated by decreased levels of cyclin B1 even in the presence of p21 siRNA. To assess whether proteasomal degradation is involved in cyclin B1 disappearance by silibinin, H1299 cells were treated with single agents in presence of proteasomal inhibitor MG132 (Fig. S2A) and cyclin B1 level was determined. While inhibition of proteasomal degradation increased cyclin B1 levels in TSA and SAHA treatments, it failed to augment cyclin B1 levels in the case of silibinin, corroborating earlier findings. To examine whether p21, the upstream key regulator of cyclin B1 expression, was being transcriptionally activated by these treatments, its mRNA expression was determined by semiquantitative RT-PCR. While silibinin alone caused only a slight increase, HDACi significantly increased p21 mRNA expression; combinatorial treatments upregulated p21 mRNA expression more robustly (Fig. 4C, top panel).

HDACi in combination with silibinin enhances histone acetylation on p21 promoter region

HDACi-induced histone hyperacetylation has been functionally linked to the induction of p21 levels in several cancer cell lines.35-37 Subsequently, to examine whether the dramatic increase in transcriptional activation of p21 expression by combinatorial treatments is associated with increased histone acetylation within the p21 promoter region, we performed ChIP assays (Fig. 4C, bottom panel) with antibodies directed against Ac-H3 and Ac-H4 and sets of primers targeting two regions of p21 promoter: region a: -324 to -676 and region b: Sp1/Sp3 binding site +41 to -343.38 After 24 h of single agent treatments with TSA and SAHA, there was a moderate increase in the levels of Ac-H3 at region a and region b of the p21 promoter (Fig. 4C-bottom panel). However, combining them with silibinin led to a ~3- to 4-fold increase in the levels of Ac-H3 bound to p21 promoter region b. Furthermore, the combinations also showed a much-stronger increase in Ac-H4 levels bound to p21 promoter at these sites compared with single agent treatments; the increase in binding being more significant (~6- to 8-fold) at the region b of the promoter. Next, using IF, we confirmed that silibinin in combination with TSA and SAHA did indeed increase the acetylation of histones (Fig. 4D), which might lead to the enhanced binding of Ac-H3 and Ac-H4 to p21 promoter resulting in its transcriptional activation. Together, these results indicate that the combinatorial treatments due to their enhanced effect on histone acetylation cause an increase in p21 gene and protein expression, which in turn leads to increased cyclin B1 degradation and thus limits its supply, preventing G2-M transition, therefore causing the cells to arrest in late G2 phase.

HDACi in combination with silibinin reduces H1299 tumor growth

The in vivo significance of the cell culture findings related to augmentation of cytotoxic effects by combination treatments was next examined in H1299 tumor xenografts (Fig. 5). Ten days after H1299 cells implantation in nude mice, animals were dosed with silibinin, TSA, SAHA alone, or a combination of TSA or SAHA with silibinin. We did not observe any significant change in body weight, diet consumption and water intake (data not shown) or any adverse effects in terms of general behavior of animals treated with these drugs alone or in combination compared with control mice throughout the study. Regarding anticancer efficacy, drug treatments either alone or in combination started showing an inhibition in tumor growth by 2 weeks, which became more visible and statistically significant at the end of the third week (Fig. 5A, left and middle panel). By the end of our study, while tumor weight (Fig. 5A, right panel) and tumor volume (Fig. 5A, left panel) were significantly lower in mice from the groups fed with a combination of TSA with silibinin than in mice from the control group, these were not significantly different than the values observed in mice from groups fed with the single agents alone. However, both tumor volume (Fig. 5A, middle panel) and weight (Fig. 5A, right panel) were significantly decreased in mice treated with a combination of SAHA with silibinin compared with the groups treated with single agents alone.

Figure 5. Effect of TSA, SAHA and silibinin alone and in combination on (A) left and middle panels: H1299 tumor volume as a function of treatment days, right panel: H1299 tumor weight on the day of xenograft harvest, (B) PCNA, TUNEL and cleaved caspase-3 positive cells, (C) p-histone H3 Ser 10 positive cells and (D) cyclin B1 positive cells in H1299 xenografts. Positive cells were quantified by counting brown-stained cells among total number of cells at 5 randomly selected fields at 40 X magnification Data are mean ± SEM; n = 6 mice per group; for IHC staining, n = 5 tumor tissues from different mice per group. Representative pictographs of tumors with selected IHC staining from control and treated groups are shown, 40x. # p < 0.05, * p < 0.001.

Evaluation of xenograft tumor tissues by IHC indicated that combination treatments significantly decreased proliferative index (Fig. 5B, left panel) and caused a marked induction in apoptosis compared with HDACi alone (Fig. 5B, middle panel). The increase in apoptosis was corroborated by increased expression of cleaved caspase-3 in these tissues (Fig. 5B, right panel). Furthermore, similar to in vitro findings, combination treatments decreased the percent of mitotic cells as indicated by a decrease in the presence of p-histone H3 Ser 10 positive nuclei (Fig. 5C, left and right panel) as well as the number of cyclin B1 positive cells (Fig. 5D, left and right panel). To further investigate whether the mechanistic effects observed in vitro, associated with a decrease in HDAC1–3 protein levels and an increase in global histone acetylation levels together with a dramatic induction of p21 by combination treatments, also exist in vivo, H1299 xenografts were analyzed for these epigenetic modifications (Fig. 6). Importantly, combination treatments caused a robust increase in both p21 positive cells (Fig. 6A, left and middle panel) as well as its increased nuclear expression (Fig. 6A, left and right panel). On the other hand, though the percentage of Ac-H3 positive tumor cells was similar between combination and single agents alone treatments (Fig. 6B, left and middle panel), there was a marked increase in its nuclear intensity as represented by its immunoreactivity score (Fig. 6B, left and right panel). With regards to HDAC 1, there was a decrease in percentage of HDAC 1 positive cells (Fig. 6C, left and middle panel) as well as its expression levels (Fig. 6C, left and right panel) in xenograft tissues from combination vs. single agents alone treatments.

Figure 6. Effect of TSA, SAHA and silibinin alone and in combination on positive cells and immunoreactivity scores of (A) p21, (B) Ac-H3 and (C) HDAC 1 in H1299 xenografts. Representative photomicrographs of tumors with p21, Ac-H3 and HDAC1 IHC staining from control and treated groups are shown, 40×. Immunoreactivity (represented by intensity of brown staining) for p21 and HDAC1 was scored as 0 (no staining), +1 (very weak cytosolic and no nuclear staining), +2 (weak cytosolic and weak nuclear staining), +3 (moderate cytosolic and moderate nuclear staining), +4 (no cytosolic staining but strong nuclear staining) and +5 (no cytosolic staining but very strong nuclear staining). Immunoreactivity (represented by intensity of brown staining in nucleus) for Ac-H3 was scored as +1 (no staining), +2 (very weak staining), +3 (weak staining), +4 (moderate staining) and +5 (strong staining). Data are mean ± SEM; n = 5 tumor tissues from different mice per group; #p < 0.05, *p < 0.001.

Discussion

It is now generally recognized that alterations in the epigenome play a significant role in the development and progression of oncogenesis, including lung tumorigenesis.2,5,7,8 At the cellular level, these alterations deregulate key cellular processes, like transcriptional control, DNA repair and cell cycle progression, which can further be modulated by environmental stressors.5,39 Thus, epigenetic modifications are considered very attractive targets for the development of therapeutic approaches.5,12,13 Accordingly, many pre-clinical and clinical trials are being undertaken, worldwide, to discover or develop agents that target DNA methylation and histone modifications.5,13 However, accumulating evidences have shown that inhibition of aberrant epigenetic modifications by combinatorial treatment of epigenome modifiers with other anticancer therapies is more effective than monotherapy5,13 and, thus, represents an effective cancer treatment strategy. Based on these perspectives, the combined use of an HDACi and a natural non-toxic agent, with established pre-clinical anti-lung cancer efficacy via pleiotropic mechanisms, appears to be a rationale strategy for anticancer treatment. Our findings suggest one such novel combination, which is safe and effective in NSCLC cases.

The choice of silibinin as anticancer agent in combination with HDACi was based on the fact that, unlike HDACi, it inhibits growth of many solid tumors of epithelial origin, including lung cancer.13,20,22,23 Silibinin, a flavonolignan isolated from milk thistle (Silybum marianum) seeds, is well known for its hepatoprotective activity, and is used clinically and as dietary supplement against liver toxicity for decades.20 Silibinin possesses strong anticancer efficacy against both carcinogen-induced primary lung tumors and chemotherapy resistant lung tumor xenografts, where it decreased tumor incidence, inhibited tumor growth and progression by downregulating inducible nitric oxide synthase and Cox-2 mediated signaling, and overcame NFκB-mediated chemoresistance, respectively.20,22,23 Additionally, growth inhibitory and pro-apoptotic effects of silibinin were recently observed in NSCLC A549 and H1299 cells.19,25 Mechanistically, silibinin modulated cytokines mediated signaling and induced cell cycle arrest accompanied by an increase in cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitors, inhibition of Cdk activity and decrease in phosphorylation of retinoblastoma (Rb) and related proteins in cell culture.19,24,25 However, the efficacy of silibinin on epigenetic events in solid tumors, including lung cancer, and its significance, has not been studied in any existing in vitro and in vivo models.

In the present study, we found that silibinin did not inhibit HDAC activity in a cell free system at physiologically achievable concentrations (data not shown), but when NSCLC cells were treated with silibinin, it did inhibit HDAC activity and significantly decreased HDAC1, 2 and 3 levels, which led to an overall increase in global histone acetylation states of H3 and H4. The implications of such an effect are tremendous, given the fact that HDACs 1–3 play an essential role in survival and proliferation of cancer cells,17,40 and their overexpression has been associated with locally advanced, de-differentiated and strongly proliferating lung tumors.2,5,8,40

Combinatorial treatment of HDACi TSA or SAHA with silibinin, against NSCLC H1299 cells, which are relatively resistant to TSA treatment,17 significantly augmented the cytotoxic effects of the single agents. The synergistic cytotoxic effects of the combinations were also associated with increased pro-apoptotic effect. Given that TSA and SAHA are known to induce histone acetylation and to de-repress target genes such as p21, triggering cell cycle arrest and apoptosis,35,36,41 it is important to note that their combinations with silibinin further caused a dramatic increase in the mRNA levels and protein expression of p21. This effect was linked to an increased Ac-H3 and Ac-H4 levels on the p21 promoter at Sp1/Sp3 binding site,38,41 together with increased global histone acetylation states. The resultant biological effect was a significant G2/M arrest, mediated by an enhanced p21-caused increased proteasomal degradation of cyclin B1 protein, the limited supply of which halts the progression of cells into mitosis, followed by apoptotic cell death. Furthermore, the fraction of cells that do manage to enter the mitotic phase undergo mitotic catastrophe, due to collapsed mitotic spindle. This is because α-tubulin, the essential component of this spindle, is a non-histone substrate of HDACs, the acetylation of which compromises the structural integrity of spindle.29,30,42 Given that silibinin also has the potential to decrease HDAC3 levels, the effect on mitotic spindle is more drastic with combination treatment, as active HDAC3 levels are essentially required for proper regulation of spindle function and kinetochore-microtubule attachments.29

Interestingly, studies in an in vivo xenograft model, validating the significance of in vitro findings, showed that unlike in vitro results, the combination of SAHA + silibinin caused a more significant effect on tumor growth compared with TSA + silibinin or single agents alone. Mechanistically, the in vivo effect mimicked the earlier molecular events, with combination showing profound anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects, which were associated with increased p21 levels, less mitotic cells and increased Ac-H3 levels in the tumor tissues. Even though the in vivo apoptotic indices of TSA + silibinin combination were greater than the SAHA+ silibinin combination, the growth suppression was greater in the latter group. One possible explanation is that either there was a delay in tumor initiation by the SAHA combination or that the apoptotic response was an early event during tumor growth, which led to an overall reduced tumor growth in this group. Harvesting the tumors as a function of time may answer this question more appropriately. Treatment with the TSA + silibinin combination was not as promising as the other combination. This may be due to the fact that SAHA, being the only HDACi approved for clinical settings,5,13,17 has better selectivity against heterogeneous tumor mass in in vivo settings.5,13 However, it is not known yet whether the reactivation of epigenetically silenced genes is the only molecular event governing the anti-tumor effects when these drugs are used in combination, or if other pleiotropic effects also play an essential role. Nonetheless, the present findings are both novel and highly significant in establishing that treatment with HDACi and silibinin would be safe and effective to suppress NSCLC growth.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

NSCLC cells H1299, H358, and H322 were exposed to vehicle (DMSO) or 75–100 μM silibinin (Sigma), 0.5 µM TSA or 5 µM SAHA (both from Cayman chemicals), alone or in combination. Cells were harvested and assessed for viability, cell cycle and apoptosis.19

Antibodies

Primary antibodies used were against HDAC1, 2, 3, cleaved caspase-9 and -3, cleaved PARP, Bcl-2, XIAP, cyclin B1, α-tubulin and p-Cdc2 Tyr 15 (Cell Signaling); Ac-H3 and Ac-H4, p-histone H3 Ser 10, phospho-Ser/Thr-Pro MPM-2 and p21 (Millipore); Cyclin B1 and Mcl-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); Survivin (Novus); Bcl-xl (BD Transduction); PCNA (Dako). Biotinylated secondary antibodies used were rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Dako), goat anti-rabbit IgG and rabbit anti-goat IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For IF analyses secondary antibodies used were Texas Red goat anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa fluor 488 rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes). The sections were mounted using Vectashield mounting reagent (H-1200) containing DAPI (Vector Labs).

HDAC activity assays and immunoprecipitation

Cells after respective treatments for 6–72 h were assayed for HDAC activity using HDAC activity kit (Biovision). For immunoprecipitation assays, cellular lysates were prepared after respective treatments and subjected to immunoprecipitation using antibodies specific to HDACs 1–3. Equal amounts of the immunoprecipitated proteins were then subjected to HDAC activity assays.

Small interfering RNA transfection

H1299 cells, at ~30% confluency, were transfected with 50 nmol/L nonspecific (control)-siRNA (Dharmacon) or p21 siRNA (Cell Signaling) using the Trans-IT TKO transfection reagent (Mirus) for 24 h. Then, drug treatments were done, and cells harvested or formalin fixed at study end.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with ChIP specific antibodies against Ac-H3 and Ac-H4 (Upstate) using ChIP assay kit (SA Biosciences); IgG used as negative control. Immunoprecipitated fractions were subjected to crosslink reversal and DNA purification. Specific primers (Sigma) were used to amplify regions of p21 gene promoter a: -324 to -676 and b: +41 to -343 based on sequences and RT-PCR protocols.38 For p21 mRNA level, RNA was isolated by TrizolR method, and specific primers for p21 and β-actin were used for amplification by RT-PCR.32,43

Tumor xenograft study

Six week old athymic (nu/nu) male nude mice, (NCI-Frederick) were subcutaneously injected with ~three million exponentially growing H1299 cells mixed with equal volume (1:1) of matrigel (BD Biosciences) on the right flank of each mouse. Ten days after implantation of cells, when tumors reached a measurable size (3 mm in diameter), only healthy animals having approximately equal tumor burden were selected carefully and distributed into six groups of six mice each. One group served as control [injected intraperitonealy (i.p.) with 1% methylcellulose in DMSO], while the other groups were given silibinin, TSA, and SAHA alone or a combination of silibinin +SAHA or silibinin +TSA until the end of the study (4 weeks). Doses of drugs in single and combination groups were kept similar: silibinin [Sigma (100 mg/kg body wt., oral gavage)]; TSA [Selleck Chemicals (0.8 mg/kg body wt., i.p.)]; and SAHA [LC Laboratories (100 mg/kg body wt., i.p.)]. Both TSA and SAHA were injected using 1% methylcellulose in DMSO as vehicle, while silibinin for oral gavage was suspended in 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose as vehicle. Mice were fed with sterilized AIN-76A rodent purified diet (Dyets, Inc.) and water ad libitum. All procedures involving animals and their care were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, UCD. Tumor volume was measured twice a week and calculated by the formula 0.5236 L1 (L2)2, where L1 is long axis and L2 is short axis of the tumor. At the end of the study, the animals were euthanized, and the tumors were excised, weighed, and a small part of the tissue was fixed in 10% buffered formalin and remainder snap frozen and stored for further analysis. Tumor tissues were analyzed by immunohistochemistry (IHC).44

Statistical analyses

Difference between different treatment groups was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni t-test using Sigma stat 2.03 software (Jandel Scientific). Two sided p values < 0.05 were considered significant. Non-significant values were represented as NS. As applicable, densitometric analysis of immunoblots was done by Scion Image program (NIH), and densitometric values adjusted to loading controls as needed. Some blots were multiplexed or stripped and reprobed with different antibodies, including those for loading control. IF images were captured on a Nikon D Eclipse C1 confocal microscope and microscopic IHC analysis was done by Zeiss Axioscop 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

NCI grants R01 CA113876 and CA102514.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- SCLC

small cell lung cancer

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- HATs

histone acetyltransferases

- HDACi

histone deacetylase inhibitors

- TSA

trichostatin A

- SAHA

suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid

- Ac-H3

acetylated histones-H3

- Ac-H4

acetylated histones-H4

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental materials may be found here: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/epigenetics/article/22070

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/epigenetics/article/22070

References

- 1.American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2012. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2012.

- 2.Risch A, Plass C. Lung cancer epigenetics and genetics. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belinsky SA, Grimes MJ, Picchi MA, Mitchell HD, Stidley CA, Tesfaigzi Y, et al. Combination therapy with vidaza and entinostat suppresses tumor growth and reprograms the epigenome in an orthotopic lung cancer model. Cancer Res. 2011;71:454–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsch FR, Lippman SM. Advances in the biology of lung cancer chemoprevention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3186–97. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song SH, Han SW, Bang YJ. Epigenetic-based therapies in cancer: progress to date. Drugs. 2011;71:2391–403. doi: 10.2165/11596690-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, Ropero S, Setien F, Ballestar ML, et al. Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10604–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500398102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg AD, Allis CD, Bernstein E. Epigenetics: a landscape takes shape. Cell. 2007;128:635–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang IV, Schwartz DA. Epigenetic control of gene expression in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1295–301. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1579PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chi P, Allis CD, Wang GG. Covalent histone modifications--miswritten, misinterpreted and mis-erased in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:457–69. doi: 10.1038/nrc2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grunstein M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature. 1997;389:349–52. doi: 10.1038/38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wade PA. Transcriptional control at regulatory checkpoints by histone deacetylases: molecular connections between cancer and chromatin. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:693–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:769–84. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bots M, Johnstone RW. Rational combinations using HDAC inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3970–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner JM, Hackanson B, Lübbert M, Jung M. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in recent clinical trials for cancer therapy. Clin Epigenetics. 2010;1:117–36. doi: 10.1007/s13148-010-0012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee MJ, Kim YS, Kummar S, Giaccone G, Trepel JB. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:639–49. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283127095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasheed WK, Johnstone RW, Prince HM. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16:659–78. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang J, Varghese DS, Gillam MC, Peyton M, Modi B, Schiltz RL, et al. Differential response of cancer cells to HDAC inhibitors trichostatin A and depsipeptide. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:116–25. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrump DS. Cytotoxicity mediated by histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer cells: mechanisms and potential clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3947–57. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mateen S, Tyagi A, Agarwal C, Singh RP, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits human nonsmall cell lung cancer cell growth through cell-cycle arrest by modulating expression and function of key cell-cycle regulators. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:247–58. doi: 10.1002/mc.20595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramasamy K, Agarwal R. Multitargeted therapy of cancer by silymarin. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:352–62. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramasamy K, Dwyer-Nield LD, Serkova NJ, Hasebroock KM, Tyagi A, Raina K, et al. Silibinin prevents lung tumorigenesis in wild-type but not in iNOS-/- mice: potential of real-time micro-CT in lung cancer chemoprevention studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:753–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh RP, Deep G, Chittezhath M, Kaur M, Dwyer-Nield LD, Malkinson AM, et al. Effect of silibinin on the growth and progression of primary lung tumors in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:846–55. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh RP, Mallikarjuna GU, Sharma G, Dhanalakshmi S, Tyagi AK, Chan DC, et al. Oral silibinin inhibits lung tumor growth in athymic nude mice and forms a novel chemocombination with doxorubicin targeting nuclear factor kappaB-mediated inducible chemoresistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8641–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tyagi A, Agarwal C, Dwyer-Nield LD, Singh RP, Malkinson AM, Agarwal R. Silibinin modulates TNF-α and IFN-γ mediated signaling to regulate COX2 and iNOS expression in tumorigenic mouse lung epithelial LM2 cells. Mol Carcinog. 2011 doi: 10.1002/mc.20851. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chittezhath M, Deep G, Singh RP, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits cytokine-induced signaling cascades and down-regulates inducible nitric oxide synthase in human lung carcinoma A549 cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1817–26. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:621–81. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raina K, Agarwal R. Combinatorial strategies for cancer eradication by silibinin and cytotoxic agents: efficacy and mechanisms. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:1466–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding M, Feng Y, Vandré DD. Partial characterization of the MPM-2 phosphoepitope. Exp Cell Res. 1997;231:3–13. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishii S, Kurasawa Y, Wong J, Yu-Lee LY. Histone deacetylase 3 localizes to the mitotic spindle and is required for kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4179–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710140105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang HY, Gu YY, Li ZG, Jia YH, Yuan L, Li SY, et al. Exposure of human lung cancer cells to 8-chloro-adenosine induces G2/M arrest and mitotic catastrophe. Neoplasia. 2004;6:802–12. doi: 10.1593/neo.04247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pines J, Hunter T. Human cyclins A and B1 are differentially located in the cell and undergo cell cycle-dependent nuclear transport. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roy S, Kaur M, Agarwal C, Tecklenburg M, Sclafani RA, Agarwal R. p21 and p27 induction by silibinin is essential for its cell cycle arrest effect in prostate carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2696–707. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dulić V, Stein GH, Far DF, Reed SI. Nuclear accumulation of p21Cip1 at the onset of mitosis: a role at the G2/M-phase transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:546–57. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillis LD, Leidal AM, Hill R, Lee PW. p21Cip1/WAF1 mediates cyclin B1 degradation in response to DNA damage. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:253–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.2.7550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumagai T, Wakimoto N, Yin D, Gery S, Kawamata N, Takai N, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (Vorinostat, SAHA) profoundly inhibits the growth of human pancreatic cancer cells. International journal of cancer 2007; 121:656-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okamoto H, Fujioka Y, Takahashi A, Takahashi T, Taniguchi T, Ishikawa Y, et al. Trichostatin A, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase, inhibits smooth muscle cell proliferation via induction of p21(WAF1) J Atheroscler Thromb. 2006;13:183–91. doi: 10.5551/jat.13.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rocchi P, Tonelli R, Camerin C, Purgato S, Fronza R, Bianucci F, et al. p21Waf1/Cip1 is a common target induced by short-chain fatty acid HDAC inhibitors (valproic acid, tributyrin and sodium butyrate) in neuroblastoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2005;13:1139–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nian H, Delage B, Pinto JT, Dashwood RH. Allyl mercaptan, a garlic-derived organosulfur compound, inhibits histone deacetylase and enhances Sp3 binding on the P21WAF1 promoter. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1816–24. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herceg Z, Vaissière T. Epigenetic mechanisms and cancer: an interface between the environment and the genome. Epigenetics. 2011;6:804–19. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.7.16262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witt O, Deubzer HE, Milde T, Oehme I. HDAC family: What are the cancer relevant targets? Cancer Lett. 2009;277:8–21. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ocker M, Schneider-Stock R. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: signalling towards p21cip1/waf1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1367–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blagosklonny MV, Robey R, Sackett DL, Du L, Traganos F, Darzynkiewicz Z, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors all induce p21 but differentially cause tubulin acetylation, mitotic arrest, and cytotoxicity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:937–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Witta SE, Gemmill RM, Hirsch FR, Coldren CD, Hedman K, Ravdel L, et al. Restoring E-cadherin expression increases sensitivity to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2006;66:944–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh RP, Sharma G, Dhanalakshmi S, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Suppression of advanced human prostate tumor growth in athymic mice by silibinin feeding is associated with reduced cell proliferation, increased apoptosis, and inhibition of angiogenesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:933–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.