Abstract

Pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies (NEBs), composed of clusters of amine [serotonin (5-HT)] and peptide-producing cells, are widely distributed within the airway mucosa of human and animal lungs. NEBs are thought to function as airway O2-sensors, since they are extensively innervated and release 5-HT upon hypoxia exposure. The small cell lung carcinoma cell line (H146) provides a useful model for native NEBs, since they contain (and secrete) 5-HT and share the expression of a membrane-delimited O2 sensor [classical NADPH oxidase (NOX2) coupled to an O2-sensitive K+ channel]. In addition, both native NEBs and H146 cells express different NADPH oxidase homologs (NOX1, NOX4) and its subunits together with a variety of O2-sensitive voltage-dependent K+ channel proteins (Kv) and tandem pore acid-sensing K+ channels (TASK). Here we used H146 cells to investigate the role and interactions of various NADPH oxidase components in O2-sensing using a combination of coimmunoprecipitation, Western blot analysis (quantum dot labeling), and electrophysiology (patchclamp, amperometry) methods. Coimmunoprecipitation studies demonstrated formation of molecular complexes between NOX2 and Kv3.3 and Kv4.3 ion channels but not with TASK1 ion channels, while NOX4 associated with TASK1 but not with Kv channel proteins. Downregulation of mRNA for NOX2, but not for NOX4, suppressed hypoxia-sensitive outward current and significantly reduced hypoxia -induced 5-HT release. Collectively, our studies suggest that NOX2/Kv complexes are the predominant O2 sensor in H146 cells and, by inference, in native NEBs. Present findings favor a NEB cell-specific plasma membrane model of O2-sensing and suggest that unique NOX/K+ channel combinations may serve diverse physiological functions.

Keywords: molecular biology, pulmonary neuroendocrine cells, chemotransduction, electrophysiology

pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies (NEBs) consist of clusters of neuroendocrine cells widely distributed within the airway mucosa of human and animal lungs (35). Although the precise function of NEBs is at present unknown, they are thought to function as hypoxia-sensitive airway sensors possibly involved in the control of breathing (2, 9). NEB cells produce amine [serotonin (5-HT)] and peptide(s), and are extensively innervated including vagal afferents derived from nodose ganglia (3). Hypoxia-induced 5-HT release from NEB cells in vivo and in vitro has been previously documented (15, 21). In addition, earlier studies have demonstrated that NEB cells express a membrane delimited O2-sensing molecular complex consisting of a O2-sensing protein coupled to an O2-sensitive K+ channel (K+O2) (37, 40). Initially, the heme-linked nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NADPH oxidase), similar to the one identified in neutrophils (29) was postulated as the universal O2-sensing protein in all peripheral O2-sensing cells, including the glomus cells of the carotid body and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (1). However, subsequent studies have postulated several alternate mechanisms operating in different O2-sensing cells. For example mitochondria, rather than a plasma membrane-delimited NADPH oxidase, are involved in O2 sensing in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and that of neonatal adrenal medulla, while AMP kinase has been proposed to play a key role in the carotid body (4, 12, 13, 34). In contrast, several lines of evidence support NADPH oxidase as the principal O2 sensor in NEBs, which may be specific to this cell type in the lung. This evidence includes coexpression of various components of NOX (i.e.. gp91phox and p22phox) and O2-sensitive voltage-gated K+ channel subunit Kv3.3a (8, 37). Further support for the role of NADPH oxidase in NEBs O2-sensing is derived from studies of NADPH oxidase deficient mouse (OD; gp91phox k/o)that demonstrated abrogated response to hypoxia in NEB cells of neontates both in vitro and in vivo (16, 18).

Other potential candidates for an O2-sensor in NEB cells include the recently identified homologues of NADPH oxidase (also referred to as low-output oxidases) found in a variety of nonphagocytic cells (19). The founder protein, gp91phox [NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2)] is predominantly expressed in phagocytic cells where it plays a critical role in host defense (31). Whereas NOX1 is expressed mostly in colonic epithelium, NOX3 is expressed mainly in the fetal kidney and inner ear (7, 20). In contrast NOX4, originally described as a renal oxidase, is widely expressed in different tissues, including lung, placenta, pancreas, bone, and blood vessels where it may be involved in various cellular processes, such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, and receptor signaling (19).

In NEB cells there are several potential K+ channels that can mediate the hypoxic response. The tandem pore acid-sensing K+ channels (TASK), are outwardly rectifying channels sensitive to changes in extracellular pH, are inhibited by extracellular acidification and are known to be involved in O2-sensing in several systems (6, 22). In addition, there are the Kv channels that are sensitive to TEA and changes in O2-availability (14, 23). However, the precise mechanism is unknown as to how these channels contribute to hypoxia sensing.

The immortalized cell line, small cell lung carcinoma cell line H146, representative of human airway chemoreceptor cells, offers several advantages over native NEBs. This includes an unlimited source of cells that are amenable to cellular and molecular studies difficult to perform, or not feasible, on native NEBs. H146 cells share many features with native NEB cells (17) including O2-sensitive K+ channels, NADPH oxidase, and serotonin content (9, 21, 25, 37). In our recent studies using multigene profiling arrays on NEB cells isolated by laser capture microdissection from human neonatal lungs, and in extracts of H146 cells we have identified expression of several novel oxidases and related protein subunits together with a variety of O2-sensitive K+ channels (10). In the present study, we investigated the function of NOX protein isoforms in mediating the hypoxic response in H146 cells using a combination of biochemical, molecular, and electrophysiological approaches. Our findings confirm the critical role of NOX2 and possibly NOX4 in O2-sensing via formation of specific NOX/K+ (O2) channel complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

The classical small cell lung carcinoma cell line H146 was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). A reference cell line, the promyelocytic cell line (HL60), representative of neutrophils was also obtained. Both H146 and HL60 cells were cultured as previously described (10, 25) using RPMI 1640 culture medium (containing l-glutamine) supplemented with 10% FCS, 2% sodium pyruvate, and 2% penicillin/streptomycin (all from GIBCO Life Technologies, Ontario, Canada) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2-95% air. Medium was changed every 2 days, and cells were passaged every 6–7 days by splitting in the ratio 1:5. Cells were used between passages 1 to 10. For electrophysiological studies, the cells were plated onto poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips and allowed to adhere for 24 h. Coverslips were then transferred to a continuously perfused recording chamber at 37°C.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry protocols, the type and source of antibodies used, were as previously reported (10). Briefly, the cell lines were plated on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips, fixed in zinc-formalin solution (Newcomer Supply, Middleton, WI) for 10 min at room temperature, and permeabilized in 0.02% Triton 100 in PBS. Cells were incubated in 4% BSA with 10% donkey serum at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were then immunostained at 4°C overnight with anti-NOX2/gp91phox and/or anti-p22phox polyclonal antibodies followed by 1 h of incubation with FITC/Texas Red-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit/goat IgG. Immunostained slides were examined under Leica confocal laser scanning microscope (model TCS 4D) with SCANWARE software, and images scanned with the multitracking mode. The excitation wavelengths of the krypton/argon laser were 488 nm for FITC and 568 nm for Texas Red, respectively. Images were processed with Photoshop CS (Adobe).

Plasmid construction and transfection for siRNA.

Silencer siRNA duplexes specific for human NOX2 gene (5′-GGAUACUAAC CAAUAGGA Utt-3′ and 5′-AUCCUAUUGGUUAGUAUCCtt-3′), Silencer siRNA duplex specific to human NOX4 (5′-XCACCACCACCACCACCATT-3′ and 5′-AAUGGUGGUGGUGGUGGU GTT-3′) and a nonsilencing human control duplex (directed against the target sequence, 5′-AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′) were purchased from Ambion (Applied Biosystems Streetsville, ON, Canada,). For stable transfections with siRNA, hairpin siRNA (NOX2 and NOX4) templates were ligated and cloned in pSilencer 4.1-CMV-neo vectors (Ambion) by a custom service from GenScript Corp (Piscataway, NJ). Propagated NOX2 and NOX4 plasmids were transfected into ∼1×105 suspension cells in 35-mm culture dishes by using LyoVec reagent (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA). Transfected cells were selected with G418, and knockdown expression levels were confirmed by Western blot analysis, immunoflourescence, and RT-PCR.

Western blot analysis and coimmunoprecipitation.

To obtain cell membrane proteins, H146 cells were briefly vortexed in hypotonic HEPES solution with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail to lyse the cells and centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellets were extracted in PBS containing 0.001% Tween 20 and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail. For coimmunoprecipitation studies, 300 μg protein from control and shRNA-treated cells were coimmunoprecipitated with either NOX2, NOX4, or Kv channels, and TASK1 antibodies [for type and source see Cutz et al., (10)] using the Seize@X Protein G Immunoprecipitation kit (Pierce) and analyzed by Western blot analysis. Specific proteins were then detected with a triple-Quantum Dot (Q-dot) labeling method. Essentially, immunoprecipitated samples trapped on beads were eluted, 5 μl of whole cell lysate [abundant in actin] was added to provide the loading control, and the mixture was separated in 7% SDS-PAGE gels (30 μl/lane) and electrophoresed. Proteins were then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After incubating with Fab fragments to light and heavy chains to block nonspecific detections of antibodies, polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were processed for NOX/K+ channel associations through immunoblotting with goat anti-NOX2, rabbit anti-Kv3.3 or Kv4.3; or rabbit anti-NOX4, goat anti-TASK1, and mouse anti-β-actin for a loading control with overnight incubation. Bound NOX and K+ channel antibodies were then detected by incubation in Qdot Secondary Antibody Conjugates Qdot705 goat anti-rabbit IgG (red)/Qdot655 horse anti-goat IgG (green) and donkey anti-mouse-AMCA (blue) conjugates diluted 1:1,000 in blocking buffer (10). To assess the strength of the NOX/K+ channel association, immunoprecipitated complexes on beads were incubated in a low concentration of 0.005% Triton X-100 prior to gel analysis and immunoblotting. ImageStation 2000MM system with Filtered Epi Illumination (KODAK 415/100 bp) was used to capture images by charge-coupled device camera.

Electrophysiology.

Voltage clamp data were obtained using the nystatin perforated patch technique as previously described (4). The pipette solution contained (in mM): 110 K gluconate, 25 KCl, 5 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, at pH 7.2, and nystatin (300–450 μg/ml). Experiments were conducted at 37°C in HEPES-buffered extracellular medium that contained (in mM): 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, at pH 7.4, with or without 0.5 μM TTX. Hypoxic solutions (PO2 = 5–15 mmHg) were generated by bubbling N2 gas and were applied to the cells by gravity flow. In voltage-clamp experiments, cells were held at −60 mV and step-depolarized to the indicated test potential (between −100 and +80 mV in 10 mV increments) for 100 ms at a frequency of 0.1 Hz. An Axopatch 200B amplifier was used to record whole cell currents (voltage-clamp) or membrane potentials (current-clamp). Voltage- and current-clamp protocols, data acquisition, and analysis were performed using pClamp 9.0 software and DigiData 1200B interface (Axon Instruments). All electrophysiological data are expressed as means ± SE and compared using the paired or independent Student's t-tests (Microcal Origin version 7.0). Drugs were prepared fresh on the day of experiments.

Carbon fiber amperometry.

Real-time secretion of 5-HT released from individual H146 cells (control vs. cells transfected with siRNA for NOX2 or NOX4) was monitored using carbon fiber amperometry after the culture dish was placed on the stage of a Nikon inverted microscope (model Optiphot-2UD; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a magnification, ×40 lens. The culture was perfused via gravity with an extracellular solution containing (in mM): 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, at pH 7.4 and 37°C. In some experiments, high K+ (30 mM) solutions were used after equimolar substitution for NaCl to depolarize cells and test for secretion. Hypoxic solution (PO2 = 15–20 mmHg) was obtained by continuously bubbling with N2. Secretion was monitored from single cells that were usually part of a cell cluster with a ProCFE low noise carbon fiber electrodes (5-μm diameter tip; Dagan) connected to a CV 23BU headstage and an Axopatch 200B amplifier set at 800 mV, a potential more positive than the oxidation potential for 5-HT. The electrode was backfilled with 3M KCl. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using Clampfit 9 (Axon Instruments); currents were filtered at 100 Hz, digitized at 250 Hz, and stored on a personal computer. Individual secretory events were quantified by measuring the charge, calculated by integrating the area under each amperometric spike. Events smaller than 3 pA were excluded from the analysis, and spike frequency was calculated as the number of spike events per minute. Samples were compared using Student's t-test, and level of significance was set at P < 0.05. Unless otherwise indicated, the data are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Downregulation of NOX mRNAs by siRNAs.

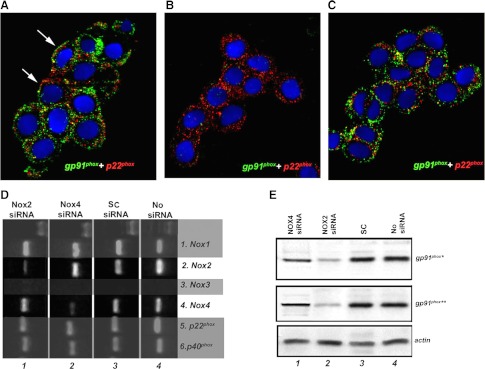

Our previous work, and that of others, suggests that pulmonary neuroendocrine cells and their immortalized derivatives (e.g., H146 cells) express a wide range of Kv channels and NOX isoforms (10, 23). While the mechanism by which membrane depolarization occurs is unknown, there is evidence that suggests that the interaction between NOX isoforms and certain Kv channels plays a key role (27). To test the potential involvement of NOX2 and NOX4 in O2-sensing, we first generated H146 cell lines deficient in either NOX2 or NOX4 isoforms. To verify the efficiency of siRNA downregulation of NOX proteins, H146 cells deficient in either NOX2 or NOX4 (termed NOX2-D or NOX4-D) cells were analyzed using immunohistochemistry, Western blot analysis, and RT-PCR. In control H146 cells, immunoreactivity for gp91phox (NOX2) and p22phox were colocalized to the plasma membrane or submembrane regions (Fig. 1A). In H146 cells transfected with NOX2 siRNA there was total loss of NOX2 (gp91phox) immunoreactivity, while p22phox immunoreactivity was preserved (Fig. 1B). In contrast, H146 cells transfected with NOX4 siRNA showed preservation of both NOX2 and p22phox immunoreactivities (Fig. 1C). The loss of respective NOX mRNAs expression was confirmed by RT-PCR. In H146 cells exposed to NOX2 siRNA, there was a significant downregulation of NOX2 mRNA without an effect on NOX4 mRNA, while in cells exposed to NOX4 siRNA only NOX4 mRNA expression was reduced, leaving NOX2 mRNA intact (Fig. 1D). These findings were further corroborated by Western blot analysis demonstrating that pretreatment with NOX2 siRNA resulted in significant reduction in NOX2 protein expression, whereas incubation with NOX4 siRNA caused almost complete loss of NOX4 protein expression (Fig. 1D). In control cells exposed to scrambled transcripts (SC), the expression of both NOX mRNAs (Fig. 1D) and proteins were preserved (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Downregulation of NOX2 and NOX4 by siRNA. A: in H146 cells, double immunoflourescence for NOX2 (gp91phox; red) and p22phox (green) show positive immunolocalization in membrane and submembrane regions (arrows). B: in cells transfected with NOX2, siRNA shows loss of NOX2 (gp91phox) immunoreactivity, while p22phox immunoreactivity is preserved. C: in contrast, NOX4 siRNA shows preservation of both NOX2 and p22phox. D: in RT-PCR studies specific downregulation of mRNA for NOX2 by NOX2 siRNA was observed, while NOX4 and other NOX components NOX1, p22phox and p40phox were unaffected. Conversely, NOX4 siRNA downregulated NOX4 mRNA, leaving NOX2 mRNA intact; NOX3 is not expressed. In Western blot analysis downregulation of NOX2 by NOX2 siRNA was observed. NOX4 siRNA has no effect on NOX2 protein expression. E, lines from left: no siRNA; scrambled transcripts (SC)-scrambled siRNA; *gp91phox, goat anti-gp91phox COOH-terminal antibody; **rabbit anti-gp91phox NH2-terminal antibody. NOX, NADPH oxidase.

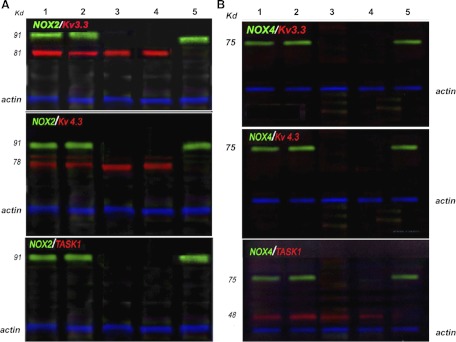

NOX/K+ channel protein-protein associations.

To study the protein-protein association between NOX and O2-sensitive K+ channels we used isolated cell membranes of H146 cells and a coimmunoprecipitation method with detection by multicolor Q-dot immunoblotting technique. In experiments with antibodies against Kv3.3/NOX2 or Kv4.3/NOX2 distinct complexes of the two proteins were observed (Fig. 2A, upper and middle). When cells were first pretreated with siRNA for NOX2, the protein band corresponding to NOX2 was absent; however, the cell membrane fraction still showed expression of the Kv3.3 and Kv4.3 ion channel proteins respectively (Fig. 2A, lane 3). Interestingly these protein-protein complexes appear to be weakly associated, since exposure to 0.005% Triton X-100, a nonionic surfactant, caused these complexes to dissociate (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 and 5 compared with lanes 1 and 2). In comparison, in immunoblots testing for the association between NOX2 and TASK1 channel, no complexes had formed (Fig. 2A, bottom). In contrast, while NOX4 did not associate with either Kv3.3. or Kv4.3 (Fig. 2B, upper and middle), it readily formed a complex with TASK1 (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 2, bottom). In a similar pattern to NOX2 downregulation, the downregulation of NOX4 by siRNA did not affect TASK1 channel protein expression (Fig. 2B, lane 3, bottom). As before, exposure to 0.005% Triton X-100 led to the dissociation of the NOX4/TASK1 protein complex (Fig. 2B, lanes 4 and 5, bottom), revealing that NOX/K+ channel interactions were relatively weak and easily dissociated by a low concentration of the nonionic detergent Triton X-100.

Fig. 2.

NOX2 and NOX4 selectively associate with voltage-activated K+ channels (Kv) and tandem pore acid-sensing K+ channels (TASK1) channels, respectively. Using the multicolor Western blot analysis triple-Quantum Dot (Q-dot) method we analyzed the interactions of NOX isoforms with various K+ channels (Kv3.3, Kv4.3, and TASK1) known to be involved in mediating the hypoxic response in various systems. A: lane 1 represents immunoprecipitation with anti-NOX2 and blotting for Kv3.3 (top), Kv4.3 (middle), and TASK1(bottom); lane 2 represents immunoprecipitation with anti-Kv3.3 (top), Kv4.3 (middle), and TASK1 (bottom) and then immunoblotting for NOX2; lane 3 represent the conditions as in lanes 1 and 2, but here cells were first treated with siRNA to NOX2. Note the knockdown of NOX2 as the 91 kDa band is absent; lanes 4 and 5 represent the immunoprecipitates treated with 0.005% Triton X-100 prior to gel analysis and immunoblotting as in lanes 1 and 2. Note that NOX2 (lane 4) or the K+ channels (lane 5) are no longer detectable, suggesting facile dissociation. B: a similar experimental design shows the results of immunoprecipitation of NOX4 and immunoblotting for Kv3.3, Kv4.3, or TASK1 (lanes 1 and 2), after knockdown of NOX4 with siRNA (lane 3) and when the complexes were prior treated with 0.005% Triton X-100 (lanes 4 and 5). The blots show that NOX4 does not associate either with Kv3.3 or Kv4.3 but associates with TASK1. Again this association is weak, and the complexes are dissociated under low nonionic detergent (lanes 4 and 5 in B). Molecular weights: NOX2, 91 kDa; Kv3.3, 81 kDa; Kv4.3, 81 kDa; NOX4, 75 kDa; TASK1, 48 kDa. Loading control is actin at 40 kDa (blue fluorescence signal).

H146 cells exposed to acute hypoxia show decrease in reactive oxygen species generation.

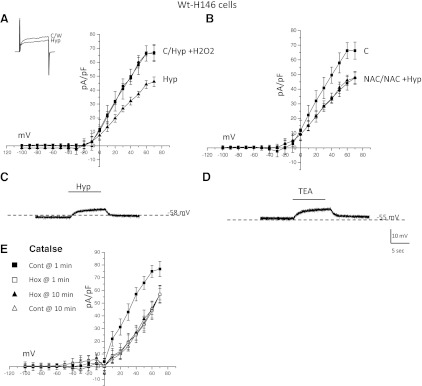

In agreement with previous reports (24, 28, 32), acute hypoxia (PO2 ∼5 mmHg) inhibited outward current in H146 cells (Fig. 3A). At a step to +30 mV, hypoxia elicited a 30.1 ± 3.6% (P < 0.05; n = 22) decrease in current density in H146 cells. During current-clamp experiments, hypoxia elicited an 8.2 ± 4.8 mV (n = 22) increase in membrane potential (Fig. 3C). No spontaneous depolarization events were found at either resting membrane potential or when stimulated with hypoxia. It was previously suggested that a decrease in reactive oxygen species (ROS) may mediate the hypoxic response in H146 cells (24). This appears to be the case since a concomitant exposure of H146 cells to hypoxia and H2O2 (50 μM) abolished hypoxic inhibition of outward current (Fig. 3A; n = 20). Exposure to higher concentrations of H2O2 resulted in either an increase in outward current beyond that seen in control or caused the loss of pipette/membrane seal (data not shown). Addition of the antioxidants N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC; 50 μM), mimicked hypoxia exposure by inhibiting outward K+ current. For example in Fig. 3B, bath application of 50 μM NAC significantly reduced outward K+ current at more positive potentials. The current density, at +30 mV, was reduced from a control value of 40.2 ± 5.2 pA/pF to 29.4 ± 3.8 pA/pF in the presence of 50 μM NAC (n = 21; Fig. 3B). When hypoxia and NAC were applied together (NAC+hyp; Fig. 3B), the outward current density for these cells was 28.9 ± 3.1 pA/pF, a value not significantly different from NAC alone (P > 0.05). Finally, we stimulated H146 cells with TEA (10 mM), a known blocker of several O2-sensitive K+ channels, as an indirect indication of ion channel function (Fig. 3D). It appears that K+ channels are open at resting potential since TEA elicited a ∼6.4 ± 3.2 mV increase in membrane potential (n = 21; Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

The effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) manipulation on outward currents in H146 cells. Current-voltage (I-V) plot for a cell exposed to normoxic control (C), hypoxia (Hyp), or modulation of ROS. Current recordings for a voltage step to +30 mV from a holding potential of −60 mV during hypoxia are shown in the inset. While hypoxia caused a decrease in outward current compared with normoxic control (A), application of H2O2 reversed the effects of hypoxia. B: administration of N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) caused a decrease in outward current, similar to hypoxia. Coadministration of hypoxia and NAC did not result in an additive response. C: during current-clamp studies hypoxia caused a reversible increase in membrane potential in H146 cells. D: bath application of tetraethylammonium (TEA) also caused an increase membrane potential in H146 cells. E: use of catalase in the patch pipette yielded similar results to NAC. Catalase caused an inhibition of outward current that occluded the hypoxic inhibition of outward current. Wt, weight.

To obtain further evidence that H2O2 plays a role in mediating the hypoxic sensitivity of H146 cells we monitored outward currents using conventional whole cell recording with catalase (1,000 U/ml) in the patch pipette. Catalase is a common enzyme used to catalyze the decomposition of H2O2. After generating an on-cell seal, the patch membrane was ruptured. Shortly after rupture of the patch, hypoxic inhibition of outward current was similar to that seen without catalase (n = 8; Fig. 3, A and E). At 10 min following breakthrough, outward current in normoxia in the catalase-dialyzed cells was reduced to a level comparable to that seen during the initial hypoxic exposure (Fig. 3E). Exposure of these cells to hypoxia at 10 min postrupture did not cause any inhibition of outward current (Fig. 3E), strongly suggesting that decreased H2O2 is a component of the hypoxia signaling pathway. This effect of catalase was prevented following prior incubation of the pipette solution with 50 mM aminotriazole, which inactivates the enzyme by binding to the peroxide binding site (data not shown).

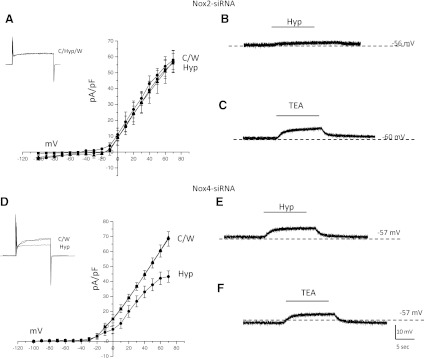

NOX2 mediates hypoxia sensing in H146 cells.

To further define the O2-sensing mechanism in H146 cells, we next investigated the effects of NOX2 or NOX4 downregulation (siRNA knockdown) on the hypoxia response. In NOX2-D cells, bath application of hypoxia did not decrease outward current at more positive potentials as seen in control H146 cells (n = 22; Fig. 4A). Similarly, during current-clamp studies no significant increase in membrane potential was observed upon exposure to hypoxia in NOX2-D cells (n = 22; Fig. 4B). The response to bath application of TEA in NOX2-D cells was maintained, confirming that the expression of functional O2-sensitive K+ is unaffected under this experimental condition (n = 22; Fig. 4C). This also suggests that at a resting membrane potential, the TEA and O2-sensitive K+ channels are open and functional, but fail to respond to hypoxia due to the absence of H2O2 generated by NOX2 (16, 24).

Fig. 4.

Hypoxia sensing is dependent on NOX2 expression. Current voltage plots for cells exposed to NOX2 or NOX4 siRNA. A: in cells deficient in NOX2, exposure to hypoxia (Hyp) did not cause a decrease in outward current compared with normoxic control (C) or wash (W). Inset depicts steps at +30 mV during hypoxia from a resting membrane potential of −60 mV. During current-clamp studies hypoxia did not elicit any membrane depolarization (B), however, application of TEA was able to cause an increase in membrane potential (C). In contrast, cells deficient in NOX4 still exhibited a hypoxic-sensitive outward current that was reversible by wash (D). Sample of outward current in inset. During current-clamp studies (E), hypoxia was able to cause an increase in membrane potential in NOX4 cells as was bath application of TEA (F).

In contrast, NOX4-D cells remained sensitive to changes in O2 since exposure to hypoxia elicited a 20.3 ± 3.2% decrease in outward current at +30 mV (P < 0.05; n = 26; Fig. 4D). However, this inhibition of outward current was significantly less compared with control native H146 cells (30.1 ± 3.6% inhibition; P < 0.05). Similarly, during current-clamp studies, while hypoxia caused an increase in membrane potential, this depolarization was significantly less than that of control H146 cells (4.2 ± 2.1 mV in NOX4-D cells compared with 8.2 ± 4.8 mV in control H146 cells; n = 26; Fig. 4E). During current-clamp studies, exposure of NOX4-D cells to TEA caused an increase in membrane potential (n = 26; 5.8 ± 3.1 mV; Fig. 4F), which was not significantly different from control H146 cells (6.4 ± 3.2 mV; Fig. 3A).

Hypoxia-induced 5-HT release.

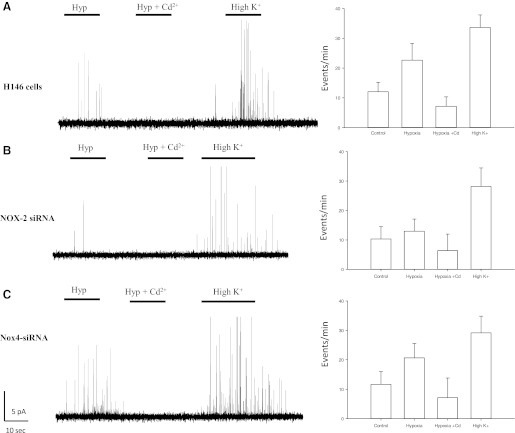

We used carbon fiber amperometry to quantify hypoxia-induced 5-HT release from H146 cells to further examine the role of NOX enzymes in O2-sensing. As shown in Fig. 5A, acute hypoxia stimulated quantal release of 5-HT from H146 cells, as did exposure to the depolarizing stimulus, using high extracellular K+ (30 mM; Fig. 5A). The secretion of 5-HT was inhibited by the general blocker of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, cadmium (Cd2+; 100 μM), suggesting that the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels play a key role in mediating secretory events in H146 cells (Fig. 5A). In NOX2-D cells, the hypoxic response was significantly reduced compared with normoxic control cells. While in control H146 cells, hypoxia-induced secretory events were 27.3 ± 6.4 events/min (n = 52; Fig. 5A), in NOX2-D cells, secretory events averaged 13.9 ± 4.8 events/min (n = 47), not significantly different from that of unstimulated control cells at 12.1 ± 5.9 events/min (Fig. 5B). In NOX4-D cells, the hypoxic-response, although still present, was significantly less compared with control H146 cells [22.1 ± 4.2 events/min (Fig. 5C)]. Bath application of Cd2+ abolished hypoxia-induced 5-HT secretion in both normal control H146 cells, as well as in NOX2-D or NOX4-D cells. In all three cell lines, stimulation via 30 mM K+ elicited a robust secretory response, indicating that it was independent of NOX expression (Figs. 5, A–C).

Fig. 5.

Hypoxia evoked 5-HT release is dependent on NOX2. Using carbon fiber amperometry, secretion of 5-HT was monitored in H146, NOX2, and NOX4 cells. A: exposure of H146 cells to hypoxia (Hyp) caused an increase in secretatory events that was blocked via administration of the general voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blocker cadmium (Cd2+). B: depolarization via 30 mM K+ also elicited a robust response in these cells. In contrast, cells deficient in NOX2 mRNA did not have a robust response to hypoxia, although they appeared to have functional secretatory machinery as 30 mM K+ caused an increase in secretatory events. C: in cells deficient in NOX4, the hypoxic response was still present, and this response was blocked via administration of Cd2+. Application of 30 mM K+ also elicited a robust response. Histograms denote frequency of secretatory events per minute during various treatments.

DISCUSSION

Our data support the theory that the combination of NOX2/Kv is a predominant sensor in the H146 cell line, representative of human pulmonary neuroendocrine chemoreceptor cells. Gene profiling of both native NEB and H146 cells have shown expression of a wide range of mRNAs encoding NOX and O2-sensitive K+ channel proteins (10). Expression of these proteins and their mRNAs in native NEB and H146 cells is significantly different from that of adjacent airway epithelial cells that do not mount a hypoxic response (10). Although the O2-sensing mechanism by NOX enzymes is not completely understood, our studies suggest that the NOX2/O2-sensitive K+ channel (e.g., Kv3.3) complexes may play a key role. Based on our studies, this model suggests that during hypoxia, a decrease in ROS production by NOX2 results in a decrease in outward current (closure of K+ channels) as also postulated by O'Kelly et al. (24). The subsequent closure of K+ channels leads to membrane depolarization, activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and subsequent 5-HT release. The effects of released 5-HT likely include hypoxia-chemotransmission via vagal afferents innervating NEB or local effects with alterations in vascular blood flow to better ventilated portions of the lung (11, 35).

Evidence for NOX2 as the predominant hypoxia sensor.

Our coimmunoprecipitation studies demonstrated that in H146 cells, NOX2 but not NOX4 formed molecular complexes with O2-sensitive Kv channel subunits that have been previously demonstrated to play a key role in mediating the hypoxic response in NEB cells (10, 37). In contrast, TASK1 was associated with NOX4 but not with NOX2. Our conclusion that NOX2 is the principal O2-sensor in human airway chemoreceptor cell line, and by inference in NEBs, is based on a number of observations. First, our previous immunolocalization studies have shown that these complexes colocalize to the plasma membrane as would be expected for an airway based sensor (10). Second, using siRNA, we demonstrate that NOX2 siRNA knockdown significantly reduced the hypoxic-response in H146 cells. The use of the siRNA approach provides a more specific means to study the O2-sensing mechanism. This is in contrast to the use of blockers of NADPH oxidase activity, such as diphenylene iodonium, which may have nonspecific effects in addition to being unable to preferentially alter activity of specific NOX isoforms. It should be noted that the specificity of diphenylene iodonium and its usefulness for studies on O2-sensing has been questioned since this compound also acts as a nonselective ion channel inhibitor in both pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and carotid body glomus cells respectively (38, 39). This decrease of NOX2 expression affected the hypoxic response at the K+O2 channel level via loss of the mediating factor (presumably H2O2). In siRNA-treated cells, expression of K+O2 was retained in addition to their being responsive to TEA (Fig. 5) and to changes in exogenous ROS modulation (data not shown). Using carbon fiber amperometry we were able to detect quantal release of 5-HT from H146 cells in response to hypoxia or depolarizing stimulus. In cells deficient in NOX2 mRNA, while hypoxia-induced 5-HT release was absent, the cells were able to release 5-HT in response to a depolarizing stimulus (30 mM K+) suggesting the secretatory machinery was still intact in NOX2-D cells.

In contrast to the association between NOX2 and Kv3.3/Kv4.3 ion channels, NOX4 was associated with TASK1. In siRNA knockdown studies, it appeared that NOX4-D cells retained a residual hypoxic response, although it was less robust compared with control H146 cells. According to our molecular studies, the decreased sensitivity to hypoxia in NOX4-D cells, compared with H146 cells, is unlikely due to a decrease in K+ channel expression, since the K+ current density profile was unaffected. It is therefore possible that the difference in hypoxic responses between these two cell models relates to reduced NOX4 activity, which may play a secondary role in the hypoxia-sensing mechanism in these cells. We conclude that NOX2 is the predominant O2-sensor in NEBs and related tumor cell model and that NOX4 may play a minor role in hypoxia sensing.

Role of NOX4 and TASK.

Our finding of an association of NOX4 with TASK1 channel is in agreement with recent studies by Lee et al. (22) showing that in HEK-293 cells, a renal cell carcinoma model that endogenously expresses NOX4, the activity of transfected TASK1 was inhibited by hypoxia. This hypoxia response was significantly augmented by cotransfection with NOX4, but not with NOX2/gp91phox. The O2-sensitivity of TASK1 was abolished by NOX4 siRNA and NADPH inhibitors, suggesting that NOX4 may represent the O2-sensor protein partner for TASK1 in this cell type. Other related studies suggest that it is O2 binding with the heme moiety of NOX4, that controls TASK1 activity and that the NADPH oxidase membrane subunit, gp22phox, might support the NOX4-TASK1 interaction. These observations, together with our findings, suggest a diversity of O2 sensors, even within the same cell type, matching specific NOX proteins with particular O2-sensitive K+ channel types (i.e., NOX2/ Kv3.3; NOX4/TASK1). It is therefore possible that NOX4/TASK1 molecular complex may constitute a secondary sensor that potentiates the activity of the NOX2/ Kv-based sensor during hypoxia, or alternatively, NOX4/TASK1 molecular complex may be involved during asphyxial (hypoxia/ hypercapnia/acidosis) responses. Further studies are required to define the precise role of NOX4 in airway chemoreceptors.

The hypoxic response is mediated via a decrease in ROS.

In other similar hypoxia-sensing systems, it has been demonstrated that exposure to reduced O2-levels leads to a decrease in ROS production, and this in turn triggers membrane depolarization and secretory events (5, 24, 32, 34). However, the precise nature and the location of the O2-sensor may differ. For example, in neonatal adrenal chromaffin cells, it has been suggested that complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain plays a key role in mediating the hypoxic response in these cells (5, 34). On the other hand, unlike neonatal adrenal chromaffin cells, it has been previously demonstrated that functional mitochondria are not required for O2-sensing in H146 cells (32). Related studies have also, indirectly, suggested that a decrease in ROS production may play a key role in mediating the hypoxia response (24). Here we show that by manipulating exogenous ROS levels, a decrease in ROS mediates the hypoxia response in H146 cells.

Thus our studies suggest that in H146 cells, and by inference in pulmonary NEBs, the hypoxia response is mediated predominantly via the activity of NOX2 proteins that produce ROS depending on ambient O2 level. The evidence for ROS/H2O2 modulation of K+ channels is derived from studies on voltage-activated K+ channels (Kv), where H2O2 is thought to act as a second messenger (36). The common feature of channels affected by H2O2 is a cysteine residue in the amino terminus shown to be highly redox sensitive (30).This amino acid terminus is believed to be intracellular and contains a site responsible for channel inactivation acting as a tethered ball and chain, which occludes the internal mouth of the channel. An O2 sensor model for NEBs, proposed by Patel and Honore (27a) incorporates our earlier model, where H2O2 producing NADPH oxidase is closely associated with O2-sensitive K+ channel (37). Similarly, BK channels contain a specific motif that confers sensitivity to ROS, similar to the large-conductance voltage and Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels (BK channel). The BK channel is known to play a role in mediating the hypoxic response in neonatal adrenomedullary chromaffin cells, likely via ROS modulation. Also part of the internal structural motif of the BK channel is known to be sensitive to changes in ROS (26, 33). Whether this is the case with the expressed Kv channels in H146 and other NEB cell related tumor cell lines remains to be elucidated.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Grants MOP-12742 and MPG-15270 (to E. Cutz and H. Yeger) from Canadian Institute for Health Research.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.B. and J.P. performed experiments; J.B. and J.P. analyzed data; J.B. and E.C. interpreted results of experiments; J.B. and J.P. prepared figures; J.B. drafted manuscript; J.B. and E.C. edited and revised manuscript; H.Y. and E.C. conception and design of research; H.Y. and E.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Present address of J. Buttigieg: Department of Biology, University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1. Acker H. Cellular oxygen sensors. Ann NY Acad Sci 718: 3–10, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bolle T, Lauweryns JM, Lommel AV. Postnatal maturation of neuroepithelial bodies and carotid body innervation: a quantitative investigation in the rabbit. J Neurocytol 29: 241–248, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brouns I, Oztay F, Pintelon I, De Proost I, Lembrechts R, Timmermans JP, Adriaensen D. Neurochemical pattern of the complex innervation of neuroepithelial bodies in mouse lungs. Histochem Cell Biol 131: 55–74, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buttigieg J, Brown ST, Lowe M, Zhang M, Nurse CA. Functional mitochondria are required for O2 but not CO2 sensing in immortalized adrenomedullary chromaffin cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C945–C956, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buttigieg J, Zhang M, Thompson R, Nurse C. Potential role of mitochondria in hypoxia sensing by adrenomedullary chromaffin cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 580: 79–85, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Campanucci VA, Fearon IM, Nurse CA. O2-sensing mechanisms in efferent neurons to the rat carotid body. Adv Exp Med Biol 536: 179–185, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng G, Cao Z, Xu X, van Meir EG, Lambeth JD. Homologs of gp91phox: cloning and tissue expression of Nox3, Nox4, and Nox5. Gene 269: 131–140, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cutz E, Fu XW, Nurse CA. Ionotropic receptors in pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies (NEB) and their possible role in modulation of hypoxia signalling. Adv Exp Med Biol 536: 155–161, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cutz E, Jackson A. Neuroepithelial bodies as airway oxygen sensors. Respir Physiol 115: 201–214, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cutz E, Pan J, Yeger H. The role of NOX2 and “novel oxidases” in airway chemoreceptor O2 sensing. Adv Exp Med Biol 648: 427–438, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cutz E, Yeger H, Pan J. Pulmonary neuroendocrine cell system in pediatric lung disease-recent advances. Pediatr Dev Pathol 10: 419–435, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Evans AM, Hardie DG, Galione A, Peers C, Kumar P, Wyatt CN. AMP-activated protein kinase couples mitochondrial inhibition by hypoxia to cell-specific Ca2+ signalling mechanisms in oxygen-sensing cells. Novartis Found Symp 272: 234–252, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Evans AM, Hardie DG, Peers C, Mahmoud A. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: mechanisms of oxygen-sensing. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 24: 13–20, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fearon IM, Thompson RJ, Samjoo I, Vollmer C, Doering LC, Nurse CA. O2-sensitive K+ channels in immortalised rat chromaffin-cell-derived MAH cells. J Physiol 545: 807–818, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fu XW, Nurse CA, Wong V, Cutz E. Hypoxia-induced secretion of serotonin from intact pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies in neonatal rabbit. J Physiol 539: 503–510, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fu XW, Wang D, Nurse CA, Dinauer MC, Cutz E. NADPH oxidase is an O2 sensor in airway chemoreceptors: evidence from K+ current modulation in wild-type and oxidase-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 4374–4379, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gazdar AF, Helman LJ, Israel MA, Russell EK, Linnoila RI, Mulshine JL, Schuller HM, Park JG. Expression of neuroendocrine cell markers l-dopa decarboxylase, chromogranin A, and dense core granules in human tumors of endocrine and nonendocrine origin. Cancer Res 48: 4078–4082, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kazemian P, Stephenson R, Yeger H, Cutz E. Respiratory control in neonatal mice with NADPH oxidase deficiency. Respir Physiol 126: 89–101, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lambeth JD. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol 4: 181–189, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laurent E, McCoy JW, 3rd, Macina RA, Liu W, Cheng G, Robine S, Papkoff J, Lambeth JD. Nox1 is over-expressed in human colon cancers and correlates with activating mutations in K-Ras. Int J Cancer 123: 100–107, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lauweryns JM, Cokelaere M, Lerut T, Theunynck P. Cross-circulation studies on the influence of hypoxia and hypoxaemia on neuro-epithelial bodies in young rabbits. Cell Tissue Res 193: 373–386, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee YM, Kim BJ, Chun YS, So I, Choi H, Kim MS, Park JW. NOX4 as an oxygen sensor to regulate TASK1 activity. Cell Signal 18: 499–507, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moudgil R, Michelakis ED, Archer SL. The role of K+ channels in determining pulmonary vascular tone, oxygen sensing, cell proliferation, and apoptosis: implications in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Microcirculation 13: 615–632, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Kelly I, Lewis A, Peers C, Kemp PJ. O2 sensing by airway chemoreceptor-derived cells. Protein kinase c activation reveals functional evidence for involvement of NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem 275: 7684–7692, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O'Kelly I, Peers C, Kemp PJ. NADPH oxidase does not account fully for O2-sensing in model airway chemoreceptor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 283: 1131–1134, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paravicini TM, Chrissobolis S, Drummond GR, Sobey CG. Increased NADPH-oxidase activity and Nox4 expression during chronic hypertension is associated with enhanced cerebral vasodilatation to NADPH in vivo. Stroke 35: 584–589, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park SJ, Chun YS, Park KS, Kim SJ, Choi SO, Kim HL, Park JW. Identification of subdomains in NADPH oxidase-4 critical for the oxygen-dependent regulation of TASK1 K+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297: C855–C864, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27a. Patel AJ, Honore E. Molecular physiology of oxygen-sensitive potassium channels. Eur Respir J 18: 221–227, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peers C, Kemp PJ. Acute oxygen sensing: diverse but convergent mechanisms in airway and arterial chemoreceptors. Respiratory Res 2: 145–149, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quinn MT, Gauss KA. Structure and regulation of the neutrophil respiratory burst oxidase: comparison with nonphagocyte oxidases. J Leukoc Biol 76: 760–781, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ruppersberg JP, Stocker M, Pongs O, Heinemann SH, Frank R, Koenen M. Regulation of fast inactivation of cloned mammalian IK(A) channels by cysteine oxidation. Nature 352: 711–714, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rybicka JM, Balce DR, Khan MF, Krohn RM, Yates RM. NADPH oxidase activity controls phagosomal proteolysis in macrophages through modulation of the lumenal redox environment of phagosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10496–10501, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Searle GJ, Hartness ME, Hoareau R, Peers C, Kemp PJ. Lack of contribution of mitochondrial electron transport to acute O2 sensing in model airway chemoreceptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 291: 332–337, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tang XD, Garcia ML, Heinemann SH, Hoshi T. Reactive oxygen species impair Slo1 BK channel function by altering cysteine-mediated calcium sensing. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11: 171–178, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thompson RJ, Buttigieg J, Zhang M, Nurse CA. A rotenone-sensitive site and H2O2 are key components of hypoxia-sensing in neonatal rat adrenomedullary chromaffin cells. Neuroscience 145: 130–141, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Van Lommel A. Pulmonary neuroendocrine cells (PNEC) and neuroepithelial bodies (NEB): chemoreceptors and regulators of lung development. Paediatr Respir Rev 2: 171–176, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Rudy B. Modulation of K+ channels by hydrogen peroxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 186: 1681–1687, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang D, Youngson C, Wong V, Yeger H, Dinauer MC, Vega-Saenz Miera E, Rudy B, Cutz E. NADPH-oxidase and a hydrogen peroxide-sensitive K+ channel may function as an oxygen sensor complex in airway chemoreceptors and small cell lung carcinoma cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 13182–13187, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weir EK, Wyatt CN, Reeve HL, Huang J, Archer SL, Peers C. Diphenyleneiodonium inhibits both potassium and calcium currents in isolated pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Appl Physiol 76: 2611–2615, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wyatt CN, Weir EK, Peers C. Diphenylene iodonium blocks K+ and Ca2+ currents in type I cells isolated from the neonatal rat carotid body. Neuroscience letters 172: 63–66, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Youngson C, Nurse C, Yeger H, Curnutte JT, Vollmer C, Wong V, Cutz E. Immunocytochemical localization on O2-sensing protein (NADPH oxidase) in chemoreceptor cells. Microsc Res Tech 37: 101–106, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]