Abstract

Angiotensin II (ANG II) stimulates production of superoxide (O2−) by NADPH oxidase (NOX) in medullary thick ascending limbs (TALs). There are three isoforms of the catalytic subunit (NOX1, 2, and 4) known to be expressed in the kidney. We hypothesized that NOX2 mediates ANG II-induced O2− production by TALs. To test this, we measured NOX1, 2, and 4 mRNA and protein by RT-PCR and Western blot in TAL suspensions from rats and found three catalytic subunits expressed in the TAL. We measured O2− production using a lucigenin-based assay. To assess the contribution of NOX2, we measured ANG II-induced O2− production in wild-type and NOX2 knockout mice (KO). ANG II increased O2− production by 346 relative light units (RLU)/mg protein in the wild-type mice (n = 9; P < 0.0007 vs. control). In the knockout mice, ANG II increased O2− production by 290 RLU/mg protein (n = 9; P < 0.007 vs. control). This suggests that NOX2 does not contribute to ANG II-induced O2− production (P < 0.6 WT vs. KO). To test whether NOX4 mediates the effect of ANG II, we selectively decreased NOX4 expression in rats using an adenovirus that expresses NOX4 short hairpin (sh)RNA. Six to seven days after in vivo transduction of the kidney outer medulla, NOX4 mRNA was reduced by 77%, while NOX1 and NOX2 mRNA was unaffected. In control TALs, ANG II stimulated O2− production by 96%. In TALs transduced with NOX4 shRNA, ANG II-stimulated O2− production was not significantly different from the baseline. We concluded that NOX4 is the main catalytic isoform of NADPH oxidase that contributes to ANG II-stimulated O2− production by TALs.

Keywords: kidney, reactive oxygen species, NADPH oxidase, thick ascending limb

superoxide (o2−) is a reactive oxygen species that plays an important role in the regulation of kidney function (13, 19, 86). Superoxide reduces urinary sodium excretion by lowering glomerular filtration rate through vasoconstriction (58), enhancing tubular-glomerular feedback (57, 57) and increasing sodium reabsorption in the thick ascending limb (70). In the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, O2− increases sodium chloride absorption by enhanced Na-K-Cl cotransport activity (41) and also increases bicarbonate absorption through enhanced Na/H exchange (42). Elevated concentrations of renal O2− have been implicated in the development of hypertension (60) and renal damage (61, 73).

O2− can be generated by NADPH oxidase, cyclooxygenase, xanthine oxidase, uncoupled nitric oxide synthase (2), and mitochondria (91); however, NADPH oxidase is the primary source of O2− production in the thick ascending limb (37, 52, 86). The NADPH oxidases are a family of enzymes composed of multiple homologous subunits. The catalytic NOX subunit has five isoforms (NOX1, NOX2, NOX3, NOX4, and NOX5) and two related enzymes, DUOX1 and DUOX2, identified thus far (43). NOX5 is not expressed in rodents (64), and NOX3 appears to be expressed only in the inner ear of human adults (47). The DUOX (dual oxidase) members are substantially different in structure and function from the NOXs with an additional transmembrane helix and long NH2-terminal domain that appears to be involved in exclusive H2O2 production in a Ca+2-dependent manner (50). They have been detected in the thyroid and salivary glands as well as the mucosal epithelium of certain gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts (24).

Chabrashvili et al. (7) found that kidneys of spontaneously hypertensive rats express NOX1, 2, and 4 but did not specifically study the isoforms of the catalytic subunit expressed in the thick ascending limb. Yang et al. (97) reported that thick ascending limbs express NOX2 and 4, but they did not study NOX1. Thus we know of no previous reports of NOX1 being expressed in the thick ascending limb. To our knowledge, there are no reports that the DUOXs are expressed in the kidney.

In the kidney, angiotensin II (ANG II) reduces urinary sodium excretion by reducing renal blood flow (40), enhancing tubuloglomerular feedback and stimulating sodium reabsorption along the nephron (20, 48). At least some of these actions are due to elevated O2− levels resulting from the stimulation of O2− production by NADPH oxidase (34, 46, 74). In endothelial cells, ANG II acutely increases O2− production by activating both NOX2- and NOX4-based NADPH oxidases (8, 30, 66, 87, 98). In the macula densa, NOX2 mediates the acute effects of ANG II on O2− production (21). Chronically, ANG II increases O2− production and NOX1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells (10, 23, 49, 94). In the thick ascending limb, ANG II acutely stimulates O2− production (65) via the ANG II type 1 (AT1) receptor; however, the NOX isoforms(s) responsible has yet to be determined.

Given the macula densa shares many characteristics with the thick ascending limb, we tested the hypothesis that ANG II-induced O2− production is mediated by NOX2-based NADPH oxidase in the thick ascending limb.

METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats obtained from Charles River Breeding Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) were maintained on chow containing 1.1% K and 0.22% Na (Purina, Richmond, IN) for ≥5 days before use. Wild-type and NOX2 knockout mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were fed regular chow. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All protocols involving animals were approved by the Henry Ford Hospital Animal Care and Use Committee (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee) in accordance with the National Institutes of Health's Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Medullary Thick Ascending Limb Suspensions

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg ip) and xylazine (20 mg/kg ip). The abdominal cavity was opened, and the kidneys were flushed with 40 ml ice-cold 0.1% collagenase in physiological saline containing the following (in mM): 130 NaCl, 2.5 NaH2PO4, 4 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 6 l-alanine, 1 Na2 citrate, 5.5 glucose, 2 Ca dilactate, and 10 HEPES pH 7.4 via retrograde perfusion of the aorta. Kidneys were then removed, and the inner strip of the outer medulla was isolated, minced, and incubated in collagenase at 37°C for 30 min, with gentle agitation of the tissue every 5 min and gassing it with 100% oxygen. The collagenase solution was removed by centrifugation at 93 g, and the tubules were resuspended in oxygenated, ice-cold physiological saline and gently stirred on ice for another 30 min. The tissue was filtered through a 250-μm nylon mesh, and the filtered material was rinsed with ice-cold physiological saline. Approximately 100 μg of total protein were used for each sample when O2− was measured.

Some minor changes were required for the mouse thick ascending limb suspensions to optimize yield. The osmolality of the physiological saline was increased to 320 mosmol/kgH2O with mannitol, the collagenase concentration was increased to 0.15%, and hyaluronidase (0.05%) was added. The times for collagenase incubation and stirring were reduced to 20 min, and the volume was reduced to 8 ml.

Western Blot

Thick ascending limb suspensions were obtained as described above and placed on ice (see Fig. 3). Tubules were then centrifuged and lysed by being vortexed in 100 μl of buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 2 mM EDTA, 300 mM sucrose, 0.1% IGEPAL, 0.1% SDS, 5 μg/ml antipain, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 4 mM benzamidine, 5 μg/ml chymostatin, 5 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 0.105 M 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Samples were centrifuged at 6,000 g for 5 min at 4°C, and protein content in the supernatant was measured using Coomassie Plus reagent (Pierce). Fifty micrograms of of total protein were loaded into each lane of a SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Ten-percent acrylamide gels were used for NOX1 and 8% acrylamide for NOX2 and 4. Proteins were separated by electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membrane was incubated in blocking buffer comprised of 5% nonfat milk in TBS-T (20 mM Tris pH 7.6, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) for 60 min and then with a 1:1,000 dilution of each NOX isoform-specific antibody in blocking buffer for 2 h at room temperature. The NOX1 antibody was a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA). The NOX2 antibody was a mouse polyclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The NOX4 antibody was a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Abcam). The membrane was washed with TBS-T and incubated with a 1:1,000 dilution in blocking buffer of a secondary antibody against the appropriate IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Biosciences) for 60 min at room temperature. The membrane was washed with TBS-T, and the reaction products were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate). The membrane was exposed to Fuji RX film and band analysis was performed using an Epson Expression 1680 scanner and density analysis software. Thick ascending limb suspensions were obtained as described above (see Fig. 7). The suspensions were then separated into two, 200-μl aliquots: control and ANG II. Following the treatment with vehicle or ANG II for 5 min at 37°C supplied with oxygen, the samples were processed as just described for Western blots.

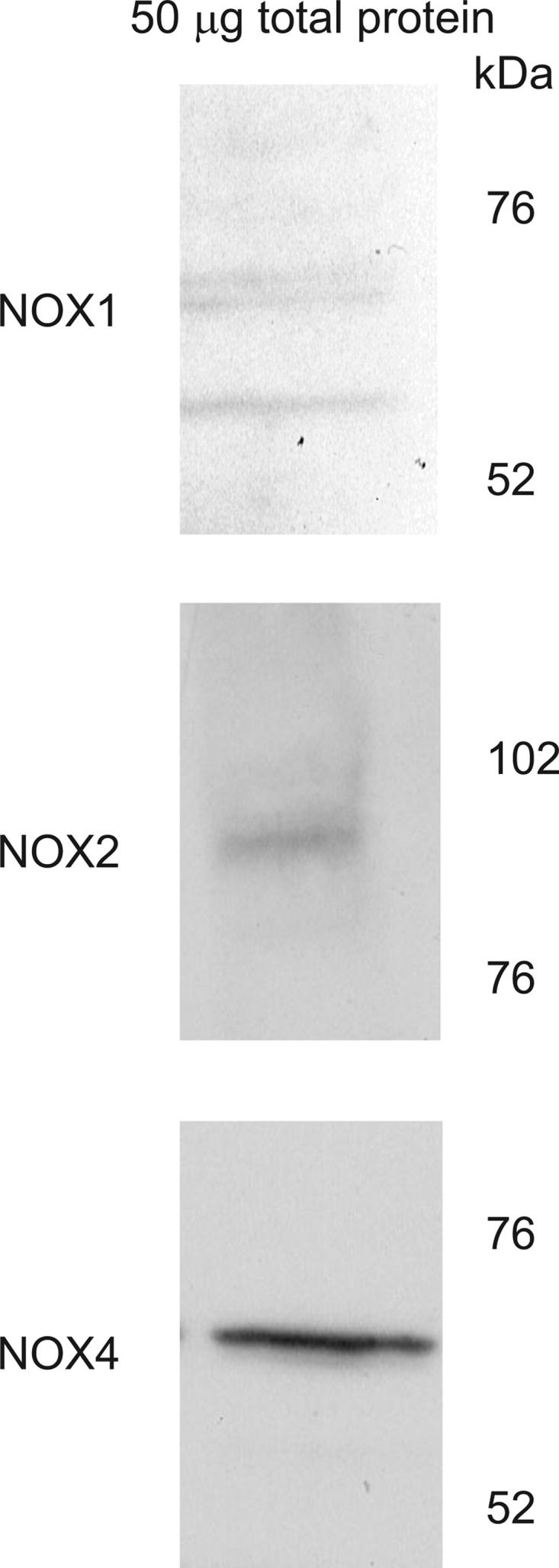

Fig. 3.

Protein expression of each NADPH oxidase isoform in 50 μg of total protein from isolated thick ascending limbs. Each Western blot was probed with isoform-specific antibodies. NOX, NADPH oxidase.

Fig. 7.

Western blot showing the effect of 1 nM ANG II for 5 min at 37° on NOX4 protein expression using an isoform-specific antibody.

Superoxide Production Using a Lucigenin-Based Assay

Two-hundred-microliter aliquots of thick ascending limb suspensions were placed in glass tubes, 700 μl of warm, oxygenated physiological saline was added, and samples were placed in a dry bath at 37° C. Lucigenin (N,N′-dimethyl-9,9′-biacridinium dinitrate; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to a final concentration of 5 μM, and the tubules were incubated for 10 min at 37°C with 100% oxygen supplied. ANG II (1 nM) or vehicle was added 5 min into the 10-min incubation with lucigenin. Samples were placed in a luminometer (model FB12/Sirius; Zylux Oak Ridge, TN) gassed with 100% oxygen and maintained at 37°C. Depending on the experimental conditions, isolated thick ascending limbs were also incubated with or without 100 μM apocynin. When studying the role of NOX4, the left kidneys were transduced with an adenovirus carrying an RNA silencing sequence against rat NOX4 as described below. Data were acquired at a rate of four measurements per second and the average luminescence per second was accumulated for 6 min. The O2− scavenger 4,5-dihydroxy-1,3-benzenedisulfonic acid (Tiron; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to a final concentration of 10 mM, and measurements were continued for 10 min. The average luminescence of the last 2 min following the addition of Tiron was then subtracted from every data point before the addition of Tiron as a means of subtracting background or nonsuperoxide luminescence. Measurements were normalized for protein content.

NOX4 Short Hairpin RNA

Recombinant replication-deficient adenoviruses encoding a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequence for rat NOX4 (AdNox4shRNA) under the control of the H1 mouse RNA polymerase promoter were constructed by ViraQuest (North Liberty, IA) as described previously (78). A 63-base annealed oligomer containing a shRNA sequence was produced (sense: C CGT TTG CAT CGA TAC TAA; bases 1358–1376 in GeneBank seq NM_053524; hairpin loop linker and antisense: TTA GTA TCG ATG CAA ACG G).

Viral injection.

Rat medullary thick ascending limbs were transduced in vivo with recombinant replication-deficient adenoviruses carrying the shRNA sequence for rat NOX4 (AdNOX4shRNA) as reported previously (71, 72, 78). Rats were anesthetized with ketamine (60 mg/kg ip) and xylazine (20 mg/kg ip), and the left kidney was exposed via a left flank incision, the fatty tissue around the renal pole was opened, and the renal artery and vein was clamped. Then, four 20-μl virus injections (4 × 1010 plaque-forming units/ml) were made using a custom-made 30-gauge needle, specific for the depth of the outer medulla and attached to polyethylene-10 tubing connected to a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) set at 20 μl/min. The needle was inserted perpendicularly to the renal capsule, parallel to the medullary rays and directed toward the medulla. Injections were made along the longitudinal axis of the kidney at 2.5-mm intervals. To avoid bleeding and leakage of the virus, the needle remained in place for 30 s after each injection was completed. The renal artery was unclamped after 8 min, the kidney was returned to the abdominal cavity, and the incision was sutured. Previously, we (71) have shown that ≥80% of thick ascending limb cells can be transduced using this technique. Thick ascending limbs from each kidney were isolated, as described above, 6–7 days posttransduction for the studies involving the NOX4 shRNA, following the time frame we established when determining when peak reduction of message was achieved.

RT-PCR.

Separate TAL suspensions from the adenovirus-injected left kidney and noninjected right kidney were prepared as described previously (79). Total RNA was isolated from the suspensions using an RNeasy Plus mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and subsequently used for RT-PCR analysis using a OneStep RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Previously published NOX isoform-specific PCR primers (84) were used to assay mRNA expression. Thermal cycler conditions for OneStep RT-PCR were as follows: 1) reverse transcription: 30 min at 50°C; 2) HotStarTaq DNA polymerase activation at 95°C for 15 min; 3) cycling at 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 5 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and 4) final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The total number of cycles used for detection of NOX isoforms in rat thick ascending limbs (Table 1) was 35 cycles using 1 μg RNA. Because of the differences observed in mRNA expression among the three NOX isoforms in thick ascending limbs, the number of cycles and amount of template RNA was adjusted to evaluate knockdown of NOX mRNA by an adenovirally delivered NOX4-specific shRNA (Fig. 6). For NOX 1 mRNA knockdown analysis, the PCR primers were as follows: 5′-GGAGTCCTCATTTTGTGGGGCAACC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGCACCCGTCTCTCTACAAATCCAGT-3′ (reverse). The total number of cycles used for NOX1, NOX2, and NOX4 was 35, 30, and 31, respectively, and the amount of RNA used was 400, 100, and 200 ng. PCR products were analyzed on 1.5% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml). Band density of the expected 560-, 605-, and 409-bp amplicons for NOX1, NOX2, and NOX 4 was analyzed. Aliquots from samples of suspensions used for the NOX4 knockdown experiments in which O2− was measured were taken before the O2− measurements and used for RT-PCR to assure there were consistent reductions in expression of NOX4.

Table 1.

mRNA abundance of NOX1, NOX2, and NOX4 in equal amounts of thick ascending limb from rats and mice as determined by RT-PCR

| Catalytic Subunit, OD units | Rat | Mouse |

|---|---|---|

| NOX1 | 8.55 | 3.13 |

| NOX2 | 462.42 | 223.16 |

| NOX4 | 120.55 | 119.77 |

OD, optical density; NOX, NADPH oxidase.

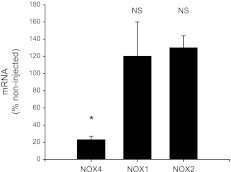

Fig. 6.

Effect of adenovirus delivery of NOX4 shRNA on NOX4 mRNA measured 6 or 7 days following transduction. (*P < 0.0001; n = 7).

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed by the Henry Ford Hospital Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology. Data were evaluated using Student's t-test for paired experiments, Student's t-test of paired differences or ANOVA using Hochberg's method to adjust for multiple testing, taking P < 0.05 as significant.

RESULTS

We first investigated the effect of 1 nM ANG II on O2− production in rat thick ascending limb suspensions. Suspensions treated with vehicle produced 183 ± 36 relative light units (RLU/mg protein) O2− in 5 min. Tubules treated with 1 nM ANG II produced 358 ± 79 RLU/mg protein in the same time, an increase of 96% (Fig. 1). Controls showed no significant increase. These data show that ANG II increases O2− production in thick ascending limb suspensions.

Fig. 1.

Effect of 1 nM ANG II on net O2− production in isolated rat thick ascending limbs. RLU, relative light units. Tubules were exposed to ANG II for 5 min (*P < 0.03; n = 6).

To test whether the effect of ANG II on O2− production is due to activation of NADPH oxidase, we used apocynin, an NADPH oxidase inhibitor. Tubules treated with 1 nM ANG II produced 358 ± 79 RLU/mg protein O2−, while those treated with ANG II plus 100 mM apocynin only produced 219 ± 62 RLU/mg protein (Fig. 2A). Apocynin had no significant effect on basal O2− production (Fig. 2B). Thus apocynin significantly reduced ANG II-stimulated O2− production.

Fig. 2.

A: effect of 100 mM apocynin on net ANG II-induced O2− production in isolated thick ascending limbs. Tubules were exposed to apocynin for 10 min and ANG II for 5 min before acquisition of data. (*P < 0.02; n = 6). B: effect of 100 mM apocynin on basal O2− production in isolated thick ascending limbs. Tubules were exposed to apocynin for 10 min and ANG II for 5 min before acquisition of data (NS; n = 6).

To begin to test which NOX isoform is responsible for ANG II-stimulated O2− production, we studied which of the catalytic subunits shown to be expressed in the kidney are present in thick ascending limbs. With the use of isoform-specific antibodies, NOX1, 2, and 4 expression was detected in thick ascending limbs. Figure 3, top, middle, and bottom, shows an aliquot from a rat thick ascending limb preparation. The three bands in Fig. 3, top, are splice variants of the NOX1 isoform, which depending on species can range from 55–60 kDa (5). The Fig. 3, middle and bottom, illustrates the presence of a single variant of NOX2 and NOX4. mRNA for NOX1, 2, and 4 was also found in thick ascending limbs from both rats and mice (Table 1).

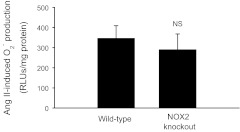

To assess the contribution of NOX2-based NADPH oxidase to ANG II-stimulated O2− production, we used NOX2 knockout mice. This is possible because thick ascending limbs from both mice and rats express NOX1, 2, and 4 (Table 1). ANG II-induced O2− production was 346 ± 63 RLU/mg protein in the wild-type mice (n = 9; Fig. 4). Similarly, ANG II-stimulated O2− production in the NOX2 knockout mice was 290 ± 78 RLU/mg protein (n = 9) (Fig. 4). These data suggest that NOX2-based NADPH oxidase does not contribute to ANG II-stimulated O2− production in thick ascending limbs.

Fig. 4.

Effect of 1 nM ANG II on net O2− production in isolated thick ascending limbs from wild-type or NOX2 knockout mice. Tubules were exposed to ANG II for 5 min before acquisition of data. (n = 9).

To determine whether NOX4 mediates the effect of ANG II in thick ascending limbs, we used isoform-specific shRNA. ANG II-stimulated O2− production was 448 ± 54 RLU/mg protein in nontransduced thick ascending limbs, but only 186 ± 23 RLU/mg protein in thick ascending limbs transduced with NOX4 shRNA (Fig. 5). We next tested whether the NOX4 shRNA affected basal O2− production. In the absence of ANG II, baseline O2− production was 141 ± 32 RLU/mg protein in the nontransduced thick ascending limbs and 138 ± 34 RLU/mg protein in the thick ascending limbs transduced with NOX4 shRNA. These data indicate that the NOX4 shRNA does not alter baseline O2− production. NOX4 mRNA was reduced by 77 ± 4% within 6–7 days, as determined by RT-PCR (Fig. 6). Transducing the thick ascending limb with NOX4 shRNA had no effect on NOX1 and NOX2 expression (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Effect of adenovirus delivery of NOX4 short hairpin (sh)RNA on ANG II-induced O2− production in isolated thick ascending limbs. Tubules were isolated 6 or 7 days after transduction with NOX4 shRNA and treated with 1 nM ANG II for 5 min before acquisition of data (*P < 0.005; n = 7).

Given that 1) the nature of our experimental design prevented us from testing all four treatments (basal, shRNA, ANG II, and ANG II plus shRNA) all at once; and 2) we did not achieve 100% knockdown of the NOX4 mRNA, it is conceivable that there is a residual acute effect of ANG II that is due to ANG II rapidly stimulating NOX4 expression as has been seen in mesangial cells (6). To test this, we performed Western blot to study whether a 5-min exposure to ANG II increases NOX4 expression. Figure 7 is a representative blot that shows that a 5-min exposure to 1 nM ANG II has no effect on the abundance of NOX4 protein (cumulative data: 0.82 vs. 0.88 arbitrary units control vs. ANG II, respectively; n = 3) in thick ascending limbs. This greatly reduces the likelihood that there is any residual acute effect of ANG II on O2− production after knocking down NOX4 that is due to a rapid stimulation of NOX4 expression.

Finally, we tested whether adding apocynin to suspensions transduced with NOX4 shRNA further reduced O2− production in the presence of ANG II. Adding apocynin had no further effect on ANG II-stimulated O2− production (Fig. 8). These data indicate that there is no apocynin-inhibitable NADPH oxidase activity in thick ascending limb suspensions transduced with NOX4 shRNA.

Fig. 8.

Effect of 100 mM apocynin on net ANG II-induced O2− production in isolated thick ascending limbs transduced with NOX4 shRNA. Tubules were exposed to apocynin for 10 min and ANG II for 5 min before acquisition of data (n = 8).

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that ANG II stimulates O2− production in the thick ascending limb via activation of NOX2-based NADPH oxidase. To address this hypothesis, we first needed to confirm that NADPH oxidase is the source of O2− in ANG II-stimulated thick ascending limbs. To do this, we used the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin. We found that apocynin significantly inhibited ANG II-stimulated O2− production but had no effect on basal production. The limits of the experimental design prevented us from testing all four treatments at once (basal, basal plus apocynin, ANG II, and ANG II plus apocynin). However, the measured O2− production in suspensions treated with ANG II plus apocynin was similar to the rates measured in untreated tubules and those treated with apocynin alone. These data demonstrate that essentially all ANG II-stimulated O2− is generated by apocynin-sensitive NADPH oxidase(s) in this segment. These results are similar to those reported by us (34) and other investigators (52).

We next set out to identify the isoform of NADPH oxidase that is involved in the observed response to ANG II. First, we studied which isoforms of the catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase found in the kidney are expressed in the thick ascending limb by Western blot and RT-PCR. Three of the isoforms of the catalytic subunit of NADPH oxidase are expressed in the kidney; NOX1, 2, and 4 (25). Thus we only examined whether thick ascending limbs express these three isoforms; we were able to detect all three at both the mRNA and protein level (Fig. 3).

Our results regarding NOX 2 and 4 are consistent with those of Yang et al. (97) who previously detected these isoforms in the thick ascending limb. Other investigators have also shown that proximal tubules (15, 15, 51, 68, 76, 81) and macula densa cells (21) express either NOX2, 4, or both. Although NOX1 has been found in mesangial cells (55), podocytes (18), and vascular smooth muscle cells (25), we are unaware of any previous indications of its presence in renal tubules with the exception of a proximal tubule cell line (44).

The macula densa and thick ascending limb share many characteristics, and NOX2-based NADPH oxidase is responsible for ANG II-stimulated O2− production in the macula densa (21). Thus we first tested whether NOX2-based NADPH oxidase mediates the effects of ANG II in the thick ascending limb. To test this, we used thick ascending limb suspensions isolated from NOX2 knockout mice. ANG II stimulated O2− production in the knockout mice in a manner similar to that of the wild-type mice. There was also no significant difference in baseline O2− production between the knockout mice and the wild-type mice. From these data, we conclude that, contrary to our hypothesis, NOX2 does not mediate ANG II-stimulated O2− production in thick ascending limbs.

We next tested the hypothesis that NOX4 mediates ANG II-induced O2− production in the thick ascending limb using adenoviral delivery of NOX4 shRNA directly into the outer medulla of rat kidneys. We found that peak knockdown of NOX4 mRNA expression was ∼77% after 6–7 days. We measured mRNA rather than protein in these experiments so that we could assess the reduction of NOX4 in each suspension that was used for measurements of O2−. We found that treating tubules with NOX4 shRNA significantly reduced ANG II-induced O2− production compared with ANG II alone. The shRNA had no effect on baseline O2− production.

As mentioned, the limits of the experimental design prevented us from testing all four treatments at once (basal, basal plus shRNA, ANG II, and ANG II treated with shRNA). Given this and the fact that NOX4 knockdown was not 100%, it is possible that there is some residual ANG II-stimulated O2− production due to activation of NOX4-based NADPH oxidase. To test for this, we first measured whether ANG II could acutely increase NOX4 expression. We found that ANG II had no effect on NOX4 expression. This result is different from mesangial cells where ANG II has been reported to increase NOX4 expression in as little as 5 min (6). These data and those showing that the measured O2− production in suspensions treated with ANG II and NOX4 shRNA were similar to rates measured in untreated tubules and those treated with shRNA alone reduce the likelihood that there is a significant residual NOX4-based NADPH oxidase activity after treatment with ANG II.

Finally, given that 1) we used mice to test the role of NOX2 and all other experiments were performed in rats; and 2) we did not specifically test for a role for NOX1, it is conceivable that there is a residual acute effect of ANG II on O2− production that is due to either 1) differences in the role of NOX2 in rats and mice; and/or 2) activation of NOX1. To test these possibilities, we examined the effect of apocynin on O2− production in the presence of ANG II after treatment with NOX4 shRNA. Adding apocynin to suspensions treated with NOX4 shRNA did not reduce the ANG II-stimulated O2− production. These data indicate that neither NOX1 or 2 or any apocynin-inhibitable NOX other than NOX4 is stimulated by ANG II in thick ascending limbs. Thus taken altogether the data indicate that NOX4-based NADPH oxidase is responsible for ANG II-stimulated O2− production in thick ascending limbs.

Our results showing that NOX4 mediates the effects of ANG II on O2− production by thick ascending limbs are novel. This is evidenced by the fact that there are few reports of ANG II specifically stimulating NOX4-based NADPH oxidase in the kidney. In renal mesangial cells, ANG II acutely increases O2− via NOX4-based NADPH oxidase (27, 28). However, ANG II has been shown to stimulate NOX4-based NADPH oxidase in a number of other cell types including vascular smooth muscle cells (36, 54, 54, 75, 88) and endothelial cells (3, 89, 89).

The interpretation of our results relies on the ability of apocynin to inhibit NOX1, 2, and 4-based NADPH oxidase activity. Although the ability of apocynin to inhibit NADPH oxidase is assumed to be due to its ability to prevent assembly of the enzyme's subunits (82), this has not been directly tested for all isoforms of the enzyme. Our data clearly indicate that it inhibits NOX4. Essentially all ANG II-induced O2− production in this study was inhibited by both NOX4 shRNA and apocynin. These results are consistent with the literature. Several studies have shown that NOX4-based NADPH oxidase activity is apocynin sensitive (4, 9, 12, 22, 62, 69, 83, 93). There is also an abundance of evidence that apocynin is effective for inhibiting NOX1 in a variety of tissues (11, 12, 17, 45, 85, 90, 93, 95). Finally, apocynin has been shown to inhibit NOX2-based NADPH oxidase (1, 1, 32, 99).

Our study shows that apocynin reduces O2− levels. We assume this is due to inhibition of production rather than simple scavenging. Although apocynin has been shown to scavenge reactive oxygen species, a much higher concentration than used in our studies is required (35). Furthermore, we (38, 80) have shown previously that the concentration we use does not scavenge O2− produced by hypoxanthine/xanthine oxidase, which is consistent with a previous study (82) that demonstrated that in cell-free systems apocynin is more effective at scavenging H2O2 at low concentrations (3–300 μM). Although we have not directly tested the mechanism of action of apocynin inhibition, it is thought that apocynin works by preventing assembly of the catalytic subunit with the p47 subunit. This would be consistent with our studies (34, 38) indicating that both ANG II-stimulated and luminal flow-stimulated O2− production is absent when p47 is absent. It is also consistent with data in mesangial cells showing that aldosterone increases O2− production via NOX1-/NOX4-based NADPH oxidase with concomitant translocation of p47 and p67 within the same time frame in an apocynin-sensitive manner (63).

Our results show that NOX4-based NADPH oxidase produces O2− rather than H2O2. This issue is somewhat contentious in the literature. There are studies indicating that NOX4 may produce H2O2 directly instead of superoxide (16, 77). However, a number of studies (26, 31, 59, 68) indicate that NOX4 first produces O2−, which is then dismutated to H2O2. In this study, O2− was detected with lucigenin, which was validated as a method to detect O2− in 1998 (56). It has been used since then to measure O2− production when trying to discriminate it from H2O2 (35, 67). To show that in our hands lucigenin is in fact measuring O2−, we added the O2− scavenger Tiron to the media at the end of each protocol and subtracted any luminescence not eliminated by Tiron. Tiron has also been used for several years to specifically scavenge O2− (33, 67). Finally, there are a number of recent studies (29, 29, 92) in a variety of tissues identifying NOX4 as the source of reactive oxygen species in which Tempol was used to reduce O2−. Tempol is a superoxide dismutase mimetic. Thus it would not eliminate H2O2 if it, rather than O2−, were the reactive oxygen species produced by NOX4-based NADPH oxidase.

It has also been suggested that NOX4-based NADPH oxidase is constitutively active and cannot be acutely stimulated by agonists (77). However, other than the work done in our laboratory indicating that ANG II rapidly stimulates O2− production in the thick ascending limb, acute regulation of NOX4 activity has also been demonstrated in other tissues such as the proximal tubule (68), mesangial cells (27, 28), and cardiac fibroblasts (14).

In summary, we have shown that ANG II stimulates NADPH oxidase-dependent O2− production in thick ascending limbs and this is due to activation of NOX4-based rather than NOX1- or NOX2-based NADPH oxidase.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants 5P01-HL-028982-30, 1P01-HL-090550-03, and 5R01-HL-070985-09 (to J. L. Garvin).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.J.M., N.J.H., and J.L.G. conception and design of research; K.J.M. and N.J.H. performed experiments; K.J.M. analyzed data; K.J.M. and J.L.G. interpreted results of experiments; K.J.M. prepared figures; K.J.M. drafted manuscript; K.J.M. and J.L.G. edited and revised manuscript; K.J.M. and J.L.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Al-Shabrawey M, Rojas M, Sanders T, Behzadian A, El-Remessy A, Bartoli M, Parpia AK, Liou G, Caldwell RB. Role of NADPH oxidase in retinal vascular inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49: 3239–3244, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J 357: 593–615, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alvarez E, Rodino-Janeiro BK, Ucieda-Somoza R, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR. Pravastatin counteracts angiotensin II-induced upregulation and activation of NADPH oxidase at plasma membrane of human endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 55: 203–212, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartsch C, Bekhite MM, Wolheim A, Richter M, Ruhe C, Wissuwa B, Marciniak A, Muller J, Heller R, Figulla HR, Sauer H, Wartenberg M. NADPH oxidase and eNOS control cardiomyogenesis in mouse embryonic stem cells on ascorbic acid treatment. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 432–443, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 87: 245–313, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Block K, Eid A, Griendling KK, Lee DY, Wittrant Y, Gorin Y. Nox4 NAD(P)H oxidase mediates Src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of PDK-1 in response to angiotensin II: role in mesangial cell hypertrophy and fibronectin expression. J Biol Chem 283: 24061–24076, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chabrashvili T, Tojo A, Onozato ML, Kitiyakara C, Quinn MT, Fujita T, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Expression and cellular localization of classic NADPH oxidase subunits in the spontaneously hypertensive rat kidney. Hypertension 39: 269–274, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chatterjee S, Feinstein SI, Dodia C, Sorokina E, Lien YC, Nguyen S, Debolt K, Speicher D, Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6 phosphorylation and subsequent phospholipase A2 activity are required for agonist-mediated activation of NADPH oxidase in mouse pulmonary microvascular endothelium and alveolar macrophages. J Biol Chem 286: 11696–11706, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng F, Wang Y, Li J, Su C, Wu F, Xia WH, Yang Z, Yu BB, Qiu YX, Tao J. Berberine improves endothelial function by reducing endothelial microparticles-mediated oxidative stress in humans. Int J Cardiol 2012. March 30 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng G, Lambeth JD. NOXO1, regulation of lipid binding, localization, and activation of Nox1 by the Phox homology (PX) domain. J Biol Chem 279: 4737–4742, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheret C, Gervais A, Lelli A, Colin C, Amar L, Ravassard P, Mallet J, Cumano A, Krause KH, Mallat M. Neurotoxic activation of microglia is promoted by a nox1-dependent NADPH oxidase. J Neurosci 28: 12039–12051, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chignalia AZ, Schuldt EZ, Camargo LL, Montezano AC, Callera GE, Laurindo FR, Lopes LR, Avellar MC, Carvalho MH, Fortes ZB, Touyz RM, Tostes RC. Testosterone induces vascular smooth muscle cell migration by NADPH oxidase and c-Src-dependent pathways. Hypertension 59: 1263–1271, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cowley AW., Jr Renal medullary oxidative stress, pressure-natriuresis, and hypertension. Hypertension 52: 777–786, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cucoranu I, Clempus R, Dikalova A, Phelan PJ, Ariyan S, Dikalov S, Sorescu D. NAD(P)H oxidase 4 mediates transforming growth factor-beta1-induced differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Circ Res 97: 900–907, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cuevas S, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Escano C, Asico L, Jones JE, Armando I, Jose PA. Role of renal DJ-1 in the pathogenesis of hypertension associated with increased reactive oxygen species production. Hypertension 59: 446–452, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dikalov SI, Dikalova AE, Bikineyeva AT, Schmidt HH, Harrison DG, Griendling KK. Distinct roles of Nox1 and Nox4 in basal and angiotensin II-stimulated superoxide and hydrogen peroxide production. Free Radic Biol Med 45: 1340–1351, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Duru EA, Fu Y, Davies MG. Urokinase requires NAD(P)H oxidase to transactivate the epidermal growth factor receptor. Surgery 2012. May 8 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eid AA, Gorin Y, Fagg BM, Maalouf R, Barnes JL, Block K, Abboud HE. Mechanisms of podocyte injury in diabetes: role of cytochrome P450 and NADPH oxidases. Diabetes 58: 1201–1211, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Evans RG, Fitzgerald SM. Nitric oxide and superoxide in the renal medulla: a delicate balancing act. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 14: 9–15, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feraille E, Doucet A. Sodium-potassium-adenosinetriphosphatase-dependent sodium transport in the kidney: hormonal control. Physiol Rev 81: 345–418, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fu Y, Zhang R, Lu D, Liu H, Chandrashekar K, Juncos LA, Liu R. NOX2 is the primary source of angiotensin II induced superoxide in the macula densa. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R707–R712, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gao S, Yuan K, Shah A, Kim JS, Park WH, Kim SH. Suppression of high pacing-induced ANP secretion by antioxidants in isolated rat atria. Peptides 32: 2467–2473, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garrido AM, Griendling KK. NADPH oxidases and angiotensin II receptor signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol 302: 148–158, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Geiszt M, Witta J, Baffi J, Lekstrom K, Leto TL. Dual oxidases represent novel hydrogen peroxide sources supporting mucosal surface host defense. FASEB J 17: 1502–1504, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gill PS, Wilcox CS. NADPH oxidases in the kidney. Antioxid Redox Signal 8: 1597–1607, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goldstein BJ, Mahadev K, Wu X, Zhu L, Motoshima H. Role of insulin-induced reactive oxygen species in the insulin signaling pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal 7: 1021–1031, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gorin Y, Ricono JM, Kim NH, Bhandari B, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE. Nox4 mediates angiotensin II-induced activation of Akt/protein kinase B in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F219–F229, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gorin Y, Ricono JM, Wagner B, Kim NH, Bhandari B, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE. Angiotensin II-induced ERK1/ERK2 activation and protein synthesis are redox-dependent in glomerular mesangial cells. Biochem J 381: 231–239, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Graham S, Gorin Y, Abboud HE, Ding M, Lee DY, Shi H, Ding Y, Ma R. Abundance of TRPC6 protein in glomerular mesangial cells is decreased by ROS and PKC in diabetes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 301: C304–C315, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Griendling KK, Minieri CA, Ollerenshaw JD, Alexander RW. Angiotensin II stimulates NADH and NADPH oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 74: 1141–1148, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ha JS, Lim HM, Park SS. Extracellular hydrogen peroxide contributes to oxidative glutamate toxicity. Brain Res 1359: 291–297, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Han W, Li H, Villar VA, Pascua AM, Dajani MI, Wang X, Natarajan A, Quinn MT, Felder RA, Jose PA, Yu P. Lipid rafts keep NADPH oxidase in the inactive state in human renal proximal tubule cells. Hypertension 51: 481–487, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hein TW, Kuo L. LDLs impair vasomotor function of the coronary microcirculation: role of superoxide anions. Circ Res 83: 404–414, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Herrera M, Silva GB, Garvin JL. Angiotensin II stimulates thick ascending limb superoxide production via protein kinase C(alpha)-dependent NADPH oxidase activation. J Biol Chem 285: 21323–21328, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heumuller S, Wind S, Barbosa-Sicard E, Schmidt HH, Busse R, Schroder K, Brandes RP. Apocynin is not an inhibitor of vascular NADPH oxidases but an antioxidant. Hypertension 51: 211–217, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Higashi M, Shimokawa H, Hattori T, Hiroki J, Mukai Y, Morikawa K, Ichiki T, Takahashi S, Takeshita A. Long-term inhibition of Rho-kinase suppresses angiotensin II-induced cardiovascular hypertrophy in rats in vivo: effect on endothelial NAD(P)H oxidase system. Circ Res 93: 767–775, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Flow increases superoxide production by NADPH oxidase via activation of Na-K-2Cl cotransport and mechanical stress in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F993–F998, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hong NJ, Silva GB, Garvin JL. PKC-α mediates flow-stimulated superoxide production in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F885–F891, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hsieh CH, Shyu WC, Chiang CY, Kuo JW, Shen WC, Liu RS. NADPH oxidase subunit 4-mediated reactive oxygen species contribute to cycling hypoxia-promoted tumor progression in glioblastoma multiforme. PLos One 6: e23945, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ito S, Arima S, Ren YL, Juncos LA, Carretero OA. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor/nitric oxide modulates angiotensin II action in the isolated microperfused rabbit afferent but not efferent arteriole. J Clin Invest 91: 2012–2019, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Juncos R, Garvin JL. Superoxide enhances Na-K-2Cl cotransporter activity in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F982–F987, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Juncos R, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Differential effects of superoxide on luminal and basolateral Na+/H+ exchange in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R79–R83, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Katsuyama M. NOX/NADPH oxidase, the superoxide-generating enzyme: its transcriptional regulation and physiological roles. J Pharm Sci 114: 134–146, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Khanna AK, Xu J, Baquet C, Mehra MR. Adverse effects of nicotine and immunosuppression on proximal tubular epithelial cell viability, tissue repair and oxidative stress gene expression. J Heart Lung Transplant 28: 612–620, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim HJ, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Oh GS, Moon HD, Kwon KB, Park C, Park BH, Lee HK, Chung SY, Park R, So HS. Roles of NADPH oxidases in cisplatin-induced reactive oxygen species generation and ototoxicity. J Neurosci 30: 3933–3946, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kopkan L, Castillo A, Navar LG, Majid DS. Enhanced superoxide generation modulates renal function in ANG II-induced hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F80–F86, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Krause KH. Tissue distribution and putative physiological function of NOX family NADPH oxidases. Jpn J Infect Dis 57: S28–S29, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kwon TH, Nielsen J, Kim YH, Knepper MA, Frokiaer J, Nielsen S. Regulation of sodium transporters in the thick ascending limb of rat kidney: response to angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F152–F165, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lassegue B, Sorescu D, Szocs K, Yin Q, Akers M, Zhang Y, Grant SL, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK. Novel gp91(phox) homologues in vascular smooth muscle cells : nox1 mediates angiotensin II-induced superoxide formation and redox-sensitive signaling pathways. Circ Res 88: 888–894, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Leto TL, Morand S, Hurt D, Ueyama T. Targeting and regulation of reactive oxygen species generation by Nox family NADPH oxidases. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 2607–2619, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li H, Han W, Villar VA, Keever LB, Lu Q, Hopfer U, Quinn MT, Felder RA, Jose PA, Yu P. D1-like receptors regulate NADPH oxidase activity and subunit expression in lipid raft microdomains of renal proximal tubule cells. Hypertension 53: 1054–1061, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li N, Yi FX, Spurrier JL, Bobrowitz CA, Zou AP. Production of superoxide through NADH oxidase in thick ascending limb of Henle's loop in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F1111–F1119, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li Y, Lappas G, nand-Srivastava MB. Role of oxidative stress in angiotensin II-induced enhanced expression of Giα proteins and adenylyl cyclase signaling in A10 vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1922–H1930, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li Y, Wang S. Glycated albumin activates NADPH oxidase in rat mesangial cells through up-regulation of p47phox. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 397: 5–11, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li Y, Zhu H, Kuppusamy P, Roubaud V, Zweier JL, Trush MA. Validation of lucigenin (bis-N-methylacridinium) as a chemilumigenic probe for detecting superoxide anion radical production by enzymatic and cellular systems. J Biol Chem 273: 2015–2023, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu R, Ren Y, Garvin JL, Carretero OA. Superoxide enhances tubuloglomerular feedback by constricting the afferent arteriole. Kidney Int 66: 268–274, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lopez B, Salom MG, Arregui B, Valero F, Fenoy FJ. Role of superoxide in modulating the renal effects of angiotensin II. Hypertension 42: 1150–1156, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mahadev K, Motoshima H, Wu X, Ruddy JM, Arnold RS, Cheng G, Lambeth JD, Goldstein BJ. The NAD(P)H oxidase homolog Nox4 modulates insulin-stimulated generation of H2O2 and plays an integral role in insulin signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol 24: 1844–1854, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Makino A, Skelton MM, Zou AP, Roman RJ, Cowley AW., Jr Increased renal medullary oxidative stress produces hypertension. Hypertension 39: 667–672, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Manning RD, Jr, Tian N, Meng S. Oxidative stress and antioxidant treatment in hypertension and the associated renal damage. Am J Nephrol 25: 311–317, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mittal M, Gu XQ, Pak O, Pamenter ME, Haag D, Fuchs DB, Schermuly RT, Ghofrani HA, Brandes RP, Seeger W, Grimminger F, Haddad GG, Weissmann N. Hypoxia induces Kv channel current inhibition by increased NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med 52: 1033–1042, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Miyata K, Rahman M, Shokoji T, Nagai Y, Zhang GX, Sun GP, Kimura S, Yukimura T, Kiyomoto H, Kohno M, Abe Y, Nishiyama A. Aldosterone stimulates reactive oxygen species production through activation of NADPH oxidase in rat mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2906–2912, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Montezano AC, Burger D, Paravicini TM, Chignalia AZ, Yusuf H, Almasri M, He Y, Callera GE, He G, Krause KH, Lambeth D, Quinn MT, Touyz RM. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced oxidase 5 (Nox5) regulation by angiotensin II and endothelin-1 is mediated via calcium/calmodulin-dependent, rac-1-independent pathways in human endothelial cells. Circ Res 106: 1363–1373, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mori T, Cowley AW., Jr Angiotensin II-NAD(P)H oxidase-stimulated superoxide modifies tubulovascular nitric oxide cross-talk in renal outer medulla. Hypertension 42: 588–593, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mukohda M, Yamawaki H, Okada M, Hara Y. Methylglyoxal augments angiotensin II-induced contraction in rat isolated carotid artery. J Pharm Sci 114: 390–398, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Munzel T, Sayegh H, Freeman BA, Tarpey MM, Harrison DG. Evidence for enhanced vascular superoxide anion production in nitrate tolerance. A novel mechanism underlying tolerance and cross-tolerance. J Clin Invest 95: 187–194, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. New DD, Block K, Bhandhari B, Gorin Y, Abboud HE. IGF-I increases the expression of fibronectin by Nox4-dependent Akt phosphorylation in renal tubular epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 302: C122–C130, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ngkelo A, Meja K, Yeadon M, Adcock I, Kirkham PA. LPS induced inflammatory responses in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells is mediated through NOX4 and Gialpha dependent PI-3kinase signalling. J Inflamm 9: 1, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ortiz PA, Garvin JL. Superoxide stimulates NaCl absorption by the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F957–F962, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Plato CF, Varela M, Garvin JL. An in vivo method for adenovirus-mediated transduction of thick ascending limbs. Kidney Int 63: 1141–1149, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Wang D, Garvin JL. Gene transfer of eNOS to the thick ascending limb of eNOS-KO mice restores the effects of l-arginine on NaCl absorption. Hypertension 42: 674–679, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Peixoto EB, Pessoa BS, Biswas SK, Lopes de Faria JB. Antioxidant SOD mimetic prevents NADPH oxidase-induced oxidative stress and renal damage in the early stage of experimental diabetes and hypertension. Am J Nephrol 29: 309–318, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ramseyer V, Garvin JL. Angiotensin II decreases NOS3 expression via nitric oxide and superoxide in the thick ascending limb. Hypertension 53: 313–318, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Saha S, Li Y, nand-Srivastava MB. Reduced levels of cyclic AMP contribute to the enhanced oxidative stress in vascular smooth muscle cells from spontaneously hypertensive rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 86: 190–198, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sedeek M, Callera G, Montezano A, Gutsol A, Heitz F, Szyndralewiez C, Page P, Kennedy CR, Burns KD, Touyz RM, Hebert RL. Critical role of Nox4-based NADPH oxidase in glucose-induced oxidative stress in the kidney: implications in type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F1348–F1358, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Serrander L, Cartier L, Bedard K, Banfi B, Lardy B, Plastre O, Sienkiewicz A, Forro L, Schlegel W, Krause KH. NOX4 activity is determined by mRNA levels and reveals a unique pattern of ROS generation. Biochem J 406: 105–114, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Silva GB, Garvin JL. TRPV4 mediates hypotonicity-induced ATP release by the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1090–F1095, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Silva GB, Garvin JL. Akt1 mediates purinergic-dependent NOS3 activation in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F646–F652, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Silva GB, Garvin JL. Rac1 mediates NaCl-induced superoxide generation in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F421–F425, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Simao S, Fraga S, Jose PA, Soares-da-Silva P. Oxidative stress plays a permissive role in alpha2-adrenoceptor-mediated events in immortalized SHR proximal tubular epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biochem 315: 31–39, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Stolk J, Hiltermann TJ, Dijkman JH, Verhoeven AJ. Characteristics of the inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation in neutrophils by apocynin, a methoxy-substituted catechol. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 11: 95–102, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sutcliffe A, Hollins F, Gomez E, Saunders R, Doe C, Cooke M, Challiss RA, Brightling CE. Increased nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4 expression mediates intrinsic airway smooth muscle hypercontractility in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185: 267–274, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Szocs K, Lassegue B, Sorescu D, Hilenski LL, Valppu L, Couse TL, Wilcox JN, Quinn MT, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK. Upregulation of Nox-based NAD(P)H oxidases in restenosis after carotid injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 21–27, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tabet F, Schiffrin EL, Callera GE, He Y, Yao G, Ostman A, Kappert K, Tonks NK, Touyz RM. Redox-sensitive signaling by angiotensin II involves oxidative inactivation and blunted phosphorylation of protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 in vascular smooth muscle cells from SHR. Circ Res 103: 149–158, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Taylor NE, Glocka P, Liang M, Cowley AW., Jr NADPH oxidase in the renal medulla causes oxidative stress and contributes to salt-sensitive hypertension in Dahl S rats. Hypertension 47: 692–698, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Thakur S, Du J, Hourani S, Ledent C, Li JM. Inactivation of adenosine A2A receptor attenuates basal and angiotensin II-induced ROS production by Nox2 in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 285: 40104–40113, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Touyz RM, Chen X, Tabet F, Yao G, He G, Quinn MT, Pagano PJ, Schiffrin EL. Expression of a functionally active gp91phox-containing neutrophil-type NAD(P)H oxidase in smooth muscle cells from human resistance arteries: regulation by angiotensin II. Circ Res 90: 1205–1213, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Van LS, Spillmann F, Lorenz M, Meloni M, Jacobs F, Egorova M, Stangl V, De GB, Schultheiss HP, Tschope C. Vascular-protective effects of high-density lipoprotein include the downregulation of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Hypertension 53: 682–687, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Weaver JR, Holman TR, Imai Y, Jadhav A, Kenyon V, Maloney DJ, Nadler JL, Rai G, Simeonov A, Taylor-Fishwick DA. Integration of pro-inflammatory cytokines, 12-lipoxygenase and NOX-1 in pancreatic islet beta cell dysfunction. Mol Cell Endocrinol 358: 88–95, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Wilcox CS. Reactive oxygen species: roles in blood pressure and kidney function. Curr Hypertens Rep 4: 160–166, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Williams CR, Lu X, Sutliff RL, Hart CM. Rosiglitazone attenuates NF-κB-mediated Nox4 upregulation in hyperglycemia-activated endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C213–C223, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Williams HC, Griendling KK. NADPH oxidase inhibitors: new antihypertensive agents? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 50: 9–16, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Wingler K, Wunsch S, Kreutz R, Rothermund L, Paul M, Schmidt HH. Upregulation of the vascular NAD(P)H-oxidase isoforms Nox1 and Nox4 by the renin-angiotensin system in vitro and in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med 31: 1456–1464, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Xiong F, Xiao D, Zhang L. Norepinephrine causes epigenetic repression of PKCε gene in rodent hearts by activating Nox1-dependent reactive oxygen species production. FASEB J 26: 2753–2763, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Yamagishi S, Nakamura K, Ueda S, Kato S, Imaizumi T. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) blocks angiotensin II signaling in endothelial cells via suppression of NADPH oxidase: a novel anti-oxidative mechanism of PEDF. Cell Tissue Res 320: 437–445, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Yang J, Lane PH, Pollock JS, Carmines PK. Protein kinase C-dependent NAD(P)H oxidase activation induced by type 1 diabetes in renal medullary thick ascending limb. Hypertension 55: 468–473, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zhang H, Schmeisser A, Garlichs CD, Plotze K, Damme U, Mugge A, Daniel WG. Angiotensin II-induced superoxide anion generation in human vascular endothelial cells: role of membrane-bound NADH-/NADPH-oxidases. Cardiovasc Res 44: 215–222, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Zhang M, Kho AL, Anilkumar N, Chibber R, Pagano PJ, Shah AM, Cave AC. Glycated proteins stimulate reactive oxygen species production in cardiac myocytes: involvement of Nox2 (gp91phox)-containing NADPH oxidase. Circulation 113: 1235–1243, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]