Abstract

Pharmacological blockade of the ANG II type 1 receptor (AT1R) is a common therapy for treatment of congestive heart failure and hypertension. Increasing evidence suggests that selective engagement of β-arrestin-mediated AT1R signaling, referred to as biased signaling, promotes cardioprotective signaling. Here, we tested the hypothesis that a β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligand TRV120023 would confer cardioprotection in response to acute cardiac injury compared with the traditional AT1R blocker (ARB), losartan. TRV120023 promotes cardiac contractility, assessed by pressure-volume loop analyses, while blocking the effects of endogenous ANG II. Compared with losartan, TRV120023 significantly activates MAPK and Akt signaling pathways. These hemodynamic and biochemical effects were lost in β-arrestin-2 knockout (KO) mice. In response to cardiac injury induced by ischemia reperfusion injury or mechanical stretch, pretreatment with TRV120023 significantly diminishes cell death compared with losartan, which did not appear to be cardioprotective. This cytoprotective effect was lost in β-arrestin-2 KO mice. The β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligand, TRV120023, has cardioprotective and functional properties in vivo, which are distinct from losartan. Our data suggest that this novel class of drugs may provide an advantage over conventional ARBs by supporting cardiac function and reducing cellular injury during acute cardiac injury.

Keywords: angiotensin, receptor, pharmacology, contractility, apoptosis

β-arrestin-biased agonism of the ANG II type 1 receptor (AT1R) is of considerable interest because of the fundamental role this receptor has in the development and progression of cardiac dysfunction (23). β-Arrestin, an adaptor molecule involved in AT1R desensitization and internalization (25), has recently been shown to mediate a parallel series of growth and prosurvival signals independent of G-protein signaling (6, 12, 17, 22). In response to mechanical stretch (22) and in response to the low-affinity β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligand Sar-Ile-Ile-ANG II, there is enhanced MAPK signaling (4, 33), increased isolated cardiomyocyte inotropy (21), and attenuated apoptosis (3).

It is known that G-protein-mediated signaling downstream of activated AT1Rs is associated with cardiac dysfunction and hypertension and that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or conventional AT1R blockers (ARBs) can mitigate adverse remodeling following cardiac injury in chronic heart (1, 2, 20). Despite the benefits of conventional ARBs in certain settings, clinical trial data suggest that these drugs may have diminished efficacy compared with ACE inhibitors (29). It remains unclear whether the cessation of protective signaling pathways downstream of the AT1R induced by traditional ARBs accounts for the differences observed clinically. Unfortunately, studies of the in vivo physiologic effects of biased agonism of the AT1R under normal conditions and during cardiac injury have been limited due to the lack of availability of a high-affinity β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligand.

Recently, novel biased ligands for the AT1R have been developed and shown to have significant effects on cardiovascular physiology, including increased cardiac contractility and activation of cytoprotective signaling pathways (32). One of these ligands, TRV120027, promotes cardiac unloading and decreases systemic and renovascular resistance in a canine model of heart failure (8) and is currently being evaluated for its effects on acute heart failure in humans (http://clinicaltrials.gov; Unique Identifier NCT01187836). With the use of a related β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligand TRV120023 (Sar-Arg-Val-Tyr-Lys-His-Pro-Ala-OH) (32), we sought to determine the mechanism for the in vivo cardiovascular response to biased agonism of the AT1R and whether the activation of β-arrestin-mediated pathways would be cardioprotective during acute cardiac injury. We show that TRV120023 infusion in wild-type (WT) mice increases cardiac contractility and stimulates cardioprotective signaling in the heart and that these effects are absent in β-arrestin-2 knockout (KO) mice. These data suggest that β-arrestin-biased agonism of the AT1R promotes beneficial biochemical and functional signaling and may provide an advantage over conventional ARBs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

Eight- to 12-wk-old control C57/B6 WT and β-arrestin-2 KO mice (9) were used for this study. Research with animals carried out for this study was handled according to approved protocols and animal welfare regulations of Duke University Medical Center's Institutional Review Boards.

Synthesis of peptides.

TRV120023 (Sar-Arg-Val-Tyr-Lys-His-Pro-Ala-OH) was synthesized by GenScript USA (Piscataway, NJ). Quality control was assessed was by high-performance chromatography and mass spectrometry as described previously (32).

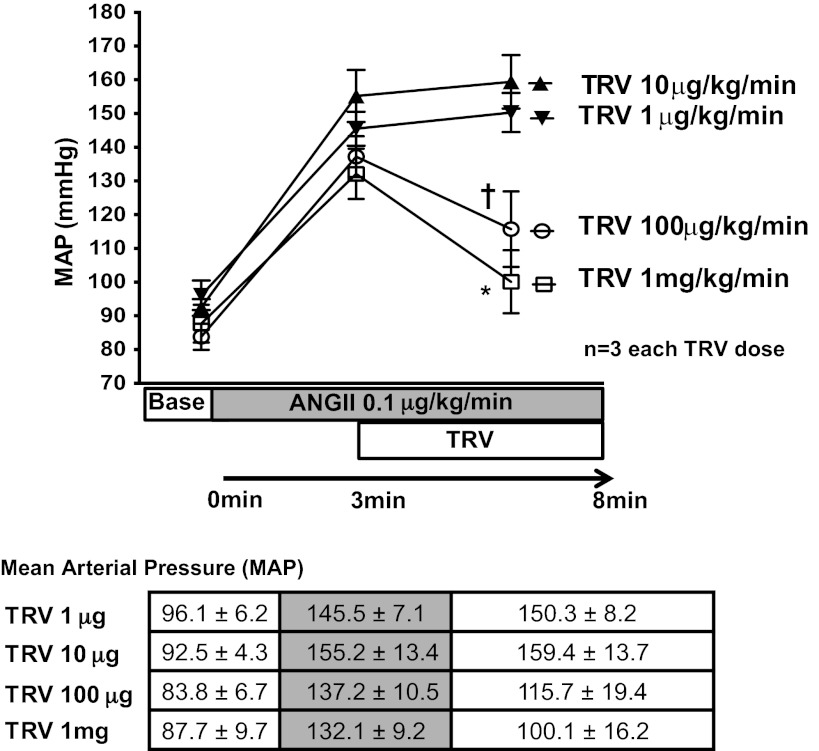

Hemodynamic study (blood pressure response).

After bilateral vagotomy, a polyethylene-50 (PE-50) catheter was inserted into the left axillary artery and connected to a Statham P23 Db pressure transducer (Gould Statham Instruments, Bayamon, Puerto Rico) for pressure monitoring. Blood pressure was recorded continuously with a pressure-recording system (MacLab, Millar Instruments, Houston, TX). Intravenous drug infusion was performed via the right jugular vein. To determine the dose of TRV120023 to use in vivo, WT mice received continuous infusion of ANG II (0.1 µg·kg−1·min−1) via the right jugular vein. After 5 min infusion, mean arterial pressure was recorded, and then graded doses of TRV120023 (from 10 μg·kg−1·min−1 to 1 mg·kg−1·min−1) were infused. Infusion of 100 μg·kg−1·min−1 TRV120023 in WT mice markedly blocked the increase in blood pressure induced by the intravenous administration of ANG II (Fig. 1) and was the dose used for the ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury in vivo studies.

Fig. 1.

TRV120023 (TRV and TRV023) decreased mean arterial pressure (MAP) in a dose-dependent manner. A steady hypertensive state was established by continuous intravenous infusion of ANG II (0.1 µg·kg−1·min−1). After establishing a hypertensive state, a continuous intravenous infusion of TRV120023 decreased mean arterial pressure in 1 mg·kg−1·min−1 and 100 μg·kg−1·min−1 infusion groups (†P < 0.05; *P < 0.01; n = 3).

Pressure-volume loop analysis.

In vivo pressure-volume (P-V) analysis was performed as described previously (18, 34). Briefly, after bilateral vagotomy, the chest was opened, and the pericardium was dissected to expose the heart. A 7-0 suture ligature was placed around the transverse aorta to manipulate loading conditions. A 1.4-Fr pressure-conductance catheter (Millar Instruments) was inserted into the left ventricle (LV) through the cardiac apex to record hemodynamics. A PE-50 catheter was inserted into the right jugular vein for drug infusion. Steady-state P-V measurements were recorded at baseline and after 5 min drug intravenous infusion (saline, TRV120023, 10 μg·kg−1·min−1 and 100 μg·kg−1·min−1; losartan, 5 mg·kg−1·min−1). P-V measurements were obtained during the increase in the afterload generated by gently pulling on the suture to transiently constrict the aorta. Subsequently, parallel conductance (Vp) was determined by 10 μl injection of 15% saline into the right jugular vein to establish the Vp of the blood pool. The derived Vp was used to correct the P-V loop data, which were recorded digitally at 1,000 Hz and analyzed with P-V analysis software (PVAN data analysis software version 3.3, Millar Instruments) as described previously (18, 34).

IR injury.

Myocardial IR was performed as described previously (14). A left thoracotomy was performed in the fourth intercostal space at the left sternal border, and ischemia was produced by ligation at the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery with an 8-0 prolene suture at the site of the vessels' emergence past the tip of the left atrium. After 30 min ligation, LAD ligation was removed and LAD blood flow restored for 45 min. Myocardial ischemia and reperfusion were confirmed visually.

Intraventricular balloon and myocardial stretch injury.

Stretch injury was induced using an ex vivo model as described previously (22). After anticoagulation and anesthetic administration, mouse hearts were excised by median thoracotomy, cannulated, and perfused at 37°C and 80–100 mmHg with Krebs-Henseleit buffer [118 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 25 mM NaHCO3, 0.5 mM Na-EDTA, and 11 mM glucose, saturated with 95% O2–5% CO2 (pH 7.4)] in a Langendorff apparatus (Hugo Sachs Elektronik-Harvard Apparatus, Germany).

Stretch injury was performed with the use of a polypropylene membrane, inserted into the LV through the mitral valve, and inflated with water to yield a LV end-diastolic pressure of 30–50 mmHg (22). The water-filled balloon was secured to a PE-50 tube and connected to a Statham P23 Db pressure transducer (Gould Instruments). LV pressure was recorded continuously with a pressure-recording system (MacLab, Millar Instruments). Hearts of age- and sex-matched mice, which were perfused without inflation of the balloon for identical periods of time, served as the perfusion control. Balloon inflation pressure was held constant with minor adjustments of volume during the experiment. After 30 min of balloon inflation, experiments were terminated, and hearts were snap frozen for analysis. Hearts were excluded from analysis if they failed to beat spontaneously when perfused or if balloon pressure was <25 or >50 mmHg for 30 min after inflation.

Immunoblotting.

LV tissue was homogenized in Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 137 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 20% glycerol, 10 mM PMSF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, aprotinin (2.5 mg/ml), and leupeptin (2.5 mg/ml). Protein concentrations were assayed with Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) protein assay reagent, and 100 μg protein was denatured by heating at 95°C for 5 min before resolving by SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting for myocardial biochemical markers was performed as described previously (18). The following dilutions of primary antibody were used: total ERK (Millipore, Billerica, MA), 1:3,000; ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), 1:1,000; total Akt (Cell Signaling Technology), 1:1,000; and phosphorylated Akt (Cell Signaling Technology), 1:1,000. Detection was carried out by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Densitometric analysis was performed with Bio-Rad Fluor-S MultiImager software.

Histological analysis.

Freshly harvested cardiac samples were placed in sucrose-PBS solution at 4°C for 2–4 h, placed in cross-section in optimum cutting temperature compound (Miles Laboratories, Elkhart, IL), and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. DNA fragmentation was detected in situ by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick end-labeling (TUNEL) (22). In brief, DNA fragments were labeled with fluorescein-conjugated deoxyuridine triphosphate with the use of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The total number of nuclei was determined by manual counting of propidium iodide fluorescence-stained nuclei in random fields per section (magnification, ×200). All TUNEL-positive nuclei were counted in each section.

Radioligand-binding studies.

A detailed description of the method used to assess binding affinity has been published previously (32). In brief, membrane preparations were made with the use of human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells with stable expression of the human AT1R with balanced conditions. Assays were initiated by the addition of [125I]-ANG II to the membrane preparations at a concentration equal to the equilibrium-binding affinity (dissociation constant). Binding assays were performed with adequate time for radioligand and competing ligand to reach temporal equilibrium. Assays were run in duplicate in polypropylene 96-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA). Nonspecific binding was defined in the presence of 1 μM saralasin. Radioactivity was quantified using a MicroBeta TriLux liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Waltham, MA). Apparent binding affinities were then analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

β-Arrestin recruitment.

The PathHunter protein complementation assay (DiscoveRx, Fremont, CA) was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol and read for chemiluminescent signaling on a PHERAStar reader (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC). In brief, complementary one-halves of β-galactosidase were fused to the carboxyl termini of the AT1R and β-arrestin-2. When cotransfected, the two fusion proteins interact upon β-arrestin-2 translocation to active receptor to form a functional enzyme, which is detected by a chemoluminescent substrate.

Inositol monophosphate accumulation.

Inositol monophosphate 1 (IP1) was measured with the IP-One Tb HTRF kit (Cisbio, Bedford, MA). Plates were read on a PHERAStar reader with the use of a time-resolved fluorescence ratio (665 nm/620 nm).

Diacylglycerol reporter assay.

To assess diacylglycerol (DAG) accumulation after ligand stimulation, a DAG reporter (DAGR) assay was performed on HEK293 cells stably overexpressing human AT1R at two different receptor densities (600 fM/mg and 2 pM/mg), transiently transfected with the fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based DAGR reporter (31). Cells were split and plated on a 35-mm dish coated with collagen. Twenty-four hours later, cells were washed with PBS and placed in imaging buffer [125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 0.2% BSA, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)]. After basal activity was recorded for 1 min, cells were stimulated with 100 nM ANG II, TRV120023, or losartan. DAGR ratio was recorded for 8 min.

Cell culture.

HEK293 cells stably expressing human AT1R were maintained as described previously (15). Cells were grown in MEM with Earle's salts, supplemented with 10% FBS and a 1:100 dilution of a penicillin-streptomycin mixture (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (33). Cells were serum starved for 12 h before stimulation.

Statistics.

Data are expressed a mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined with a one-way ANOVA (with Tukey's test for multiple comparisons) using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software). For comparisons with the Sham condition, Wilcoxon rank sum tests were performed to confirm statistical significance. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

β-Arrestin-biased AT1R ligand enhances cardiac contractility.

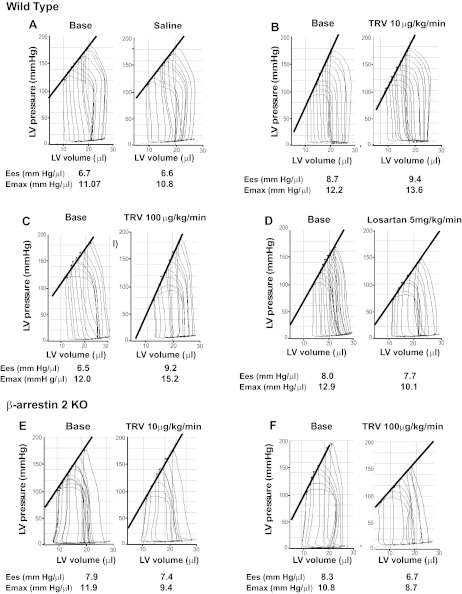

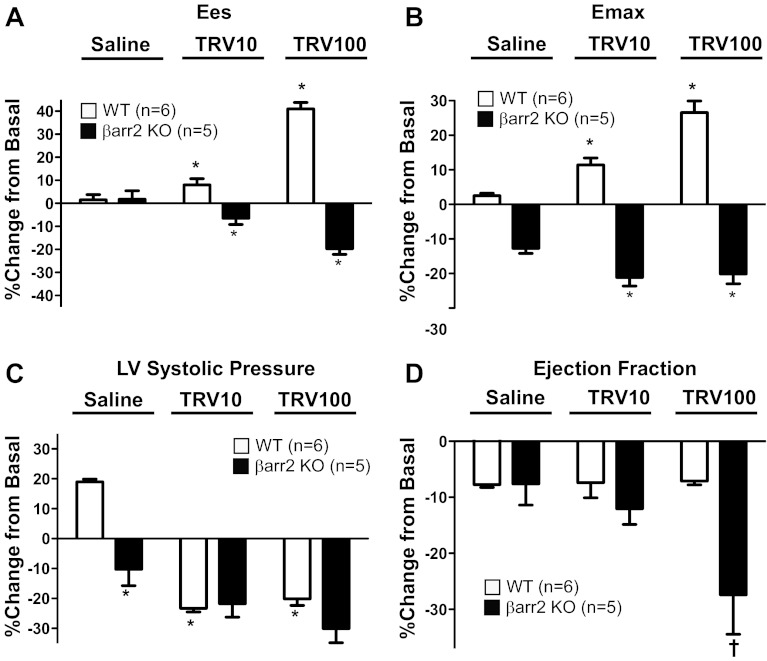

To test whether TRV120023 affects cardiac function in vivo, we performed P-V loop analysis on both WT and β-arrestin-2 KO mice (Figs. 2 and 3). In WT mice, intravenous infusion of TRV120023 increased end-systolic elastance (Ees) and maximal elastance (Emax), measures of cardiac contractility that are independent of loading conditions (Fig. 2, A–C; Table 1). In contrast, intravenous infusion of the unbiased AT1R antagonist, losartan, decreased contractility significantly (Fig. 2D; Table 1). In β-arrestin-2 KO mice, no increase in contractility, as measured by Ees and Emax, was observed with TRV120023 infusion (Figs. 2, E and F, and 3, A and B; Table 2). Infusion of TRV120023 caused a similar reduction in LV systolic pressure in both WT and β-arrestin-2 KO mice, but only in the β-arrestin-2 KO mice was there a fall in ejection fraction (Fig. 3, C and D; Tables 1 and 2). These findings suggest that the increase in contractility caused by TRV120023 administration is dependent on β-arrestin-2, whereas the reduction in blood pressure is G-protein mediated and independent of β-arrestin-2. Importantly, the administration of losartan decreased cardiac contractility and LV systolic pressure, consistent with complete blockade of both β-arrestin-2 and G-protein AT1R signaling.

Fig. 2.

Representative pressure-volume loops and changes in end-systolic elastance (Ees) and maximal elastance (Emax) in wild-type (WT) and β-arrestin-2 knockout (KO) mice. WT mice before and after infusion with: A: saline, B: TRV120023 (10 μg·kg−1·min−1), C: TRV120023 (100 μg·kg−1·min−1), and D: losartan (5 mg·kg−1·min−1). β-Arrestin-2 KO mice before and after infusion with: E: TRV120023 (10 μg·kg−1·min−1) and F: TRV120023 (100 μg·kg−1·min−1). LV, left ventricle.

Fig. 3.

Enhanced contractility and cardiac function by TRV120023 is β-arrestin-2 (βarr2) dependent. A and B: myocardial contractility measures (Ees and Emax) were increased significantly in WT treated with TRV120023 [10 μg·kg−1·min−1 (TRV10) and 100 μg·kg−1·min−1 (TRV100)]. In β-arrestin-2 KO mice, Ees and Emax were decreased in a dose-dependent manner (*P < 0.001 for the saline-infused group vs. TRV120023-infused groups of the corresponding genotype; WT, n = 6; β-arrestin-2 KO, n = 5). C: LV systolic pressure was decreased significantly in the TRV120023-infusion group (*P < 0.001 for the saline-infused group vs. TRV120023-infused groups of the corresponding genotype and for saline-infused WT vs. β-arrestin-2 KO; WT, n = 6; β-arrestin-2 KO, n = 5). D: ejection fraction was not changed in TRV10- and TRV100-infusion groups in WT but was decreased in β-arrestin-2 KO mice (†P < 0.01 for β-arrestin-2 KO infused with TRV100 vs. saline-treated β-arrestin-2 KO and TRV100-treated WT; WT, n = 6; β-arrestin-2 KO, n = 5).

Table 1.

Wild-type mice: hemodynamic parameters in response to a β-arrestin-biased AT1R agonist

| Saline (n = 5) |

TRV120023 10 μg (n = 6) |

TRV120023 100 μg (n = 6) |

Losartan 5 mg (n = 6) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Saline | Base | TRV | Base | TRV | Base | Losartan | |

| HR, beats/min | 477 ± 10 | 469 ± 9 | 459 ± 29 | 410 ± 46 | 460 ± 10 | 460 ± 30 | 475 ± 16 | 438 ± 17 |

| LVSP, mmHg | 94.4 ± 13.3 | 107.3 ± 19.5 | 101.6 ± 8.7 | 84.2 ± 13.8 | 103.1 ± 13.7 | 82.5 ± 9.1 | 106.6 ± 5.2 | 82.5 ± 8.6 |

| ESP, mmHg | 87.4 ± 5.1 | 103.7 ± 6.5 | 97.0 ± 4.9 | 74.3 ± 5.8* | 97.9 ± 3.1 | 78.7 ± 6.9† | 102.5 ± 1.6 | 75.4 ± 3.3‡ |

| EDP, mmHg | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 1.3 | 6.7 ± 2.2 | 7.1 ± 1.6 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 5.7 ± 1.4 |

| ESV, μl | 10.0 ± 1.2 | 12.4 ± 1.2 | 6.7 ± 0.7 | 8.3 ± 2.2 | 11.8 ± 1.2 | 13.0 ± 1.2 | 9.7 ± 1.8 | 12.8 ± 2.5 |

| EDV, μl | 24.5 ± 2.1 | 27.4 ± 2.7 | 17.9 ± 0.8 | 18.9 ± 2.1 | 23.8 ± 1.7 | 25.1 ± 2.1 | 19.6 ± 2.4 | 22.5 ± 2.0 |

| Stroke volume, μl | 16.1 ± 1.3 | 16.4 ± 1.4 | 12.5 ± 0.6 | 11.5 ± 0.6 | 14.2 ± 0.6 | 14.4 ± 1.1 | 11.2 ± 1.0 | 12.0 ± 1.4 |

| Systolic function | ||||||||

| EF, % | 62.6 ± 2.0 | 57.6 ± 0.5 | 68.1 ± 2.8 | 63.4 ± 7.5 | 58.1 ± 1.6 | 54.0 ± 1.2 | 57.3 ± 3.1 | 52.4 ± 6.7 |

| dP/dtmax, mmHg/s | 8,701 ± 5,467 | 9,680 ± 718 | 8,152 ± 392 | 5,498 ± 487* | 8,476 ± 215 | 6,546 ± 698 | 9,405 ± 431 | 6,242 ± 859‡ |

| Ees, mmHg/μl | 6.7 ± 0.4 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 6.5 ± 0.4 | 9.2 ± 0.5‡ | 8.0 ± 0.7 | 7.7 ± 0.5 |

| Emax, mmHg/μl | 11.07 ± 0.7 | 10.8 ± 0.5 | 12.2 ± 0.3 | 13.6 ± 0.6 | 12.0 ± 0.4 | 15.2 ± 0.3‡ | 12.9 ± 0.4 | 10.1 ± 0.4‡ |

| Diastolic function | ||||||||

| dP/dtmin, mmHg/s | −7,141 ± 433 | −8,610 ± 601 | −6,881 ± 543 | −5,371 ± 734 | −8,247 ± 397 | −6,557 ± 698 | −9,912 ± 509 | −6,552 ± 835‡ |

| EDPVR, mmHg/μl | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| Tau (τ), ms | 11.9 ± 0.4 | 11.1 ± 0.3 | 14.6 ± 1.5 | 14.8 ± 2.7 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 10.6 ± 0.6 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 10.7 ± 1.0 |

Left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP) and end-systolic pressure (ESP) were decreased significantly after TRV120023 (TRV) and losartan infusion groups. Cardiac contractility [end-systolic elastance (Ees) and maximal elastance (Emax)] was increased significantly in TRV120023 100 μg · kg−1 · min−1 infusion group. (

P < 0.01;

P < 0.05;

P < 0.001;

n = 5–6/group). P values reflect comparisons with basal condition within the same treatment group with the use of 1-way ANOVA. AT1R, ANG II type 1 receptor; HR, heart rate; EDP, end-diastolic pressure; ESV, end-systolic volume; EDV, end-diastolic volume; EF, ejection fraction; dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin, maximum and minimum rate of pressure change in the ventricle, respectively; EDPVR, EDP-volume relation; τ, isovolumic relaxation constant.

Table 2.

β-Arrestin-2 knockout mice: hemodynamic parameters in response to a β-arrestin-biased AT1R agonist

| Saline (n = 5) |

TRV120023 10 μg (n = 5) |

TRV120023 100 μg (n = 5) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Saline | Base | TRV | Base | TRV | |

| HR, beats/min | 449 ± 13 | 419 ± 15 | 401 ± 19 | 359 ± 17 | 404 ± 21 | 359 ± 27 |

| LVSP, mmHg | 110.1 ± 1.6 | 101.1 ± 2.4 | 100.3 ± 1.6 | 83.4 ± 1.7* | 96.7 ± 0.9 | 64.1 ± 1.9* |

| ESP, mmHg | 108.1 ± 3.6 | 97.1 ± 7.2 | 96.9 ± 6.9 | 75.6 ± 1.8* | 89.6 ± 3.3 | 62.9 ± 6.2* |

| EDP, mmHg | 4.1 ± 2.4 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 4.1 ± 1.8 | 6.2 ± 2.2 | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 4.6 ± 1.5 |

| ESV, μl | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 9.7 ± 1.3 | 7.7 ± 0.8 | 10.1 ± 1.3 | 8.6 ± 1.0 | 13.6 ± 1.5 |

| EDV, μl | 17.7 ± 1.6 | 19.8 ± 2.0 | 17.7 ± 1.5 | 19.6 ± 2.2 | 19.65 ± 3.4 | 22.9 ± 3.8 |

| Stroke volume, μl | 9.8 ± 2.1 | 10.7 ± 0.9 | 11.7 ± 1.3 | 11.6 ± 1.89 | 13.7 ± 2.8 | 11.5 ± 2.1 |

| Systolic function | ||||||

| EF, % | 62.8 ± 1.1 | 53.2 ± 4.1 | 63.2 ± 2.6 | 55.8 ± 3.7 | 64.9 ± 1.7 | 46.9 ± 4.2* |

| dP/dtmax, mmHg/s | 7,663 ± 437 | 5,451 ± 603 | 5,727 ± 871 | 3,995 ± 504 | 5,596 ± 1,325 | 3,229 ± 593† |

| Ees, mmHg/μl | 7.4 ± 0.2 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.4 | 7.4 ± 0.3 | 8.3 ± 0.3 | 6.7 ± 0.1* |

| Emax, mmHg/μl | 13.9 ± 0.6 | 12.1 ± 0.6 | 11.9 ± 0.5 | 9.4 ± 0.2* | 10.8 ± 0.4 | 8.7 ± 0.3* |

| Diastolic function | ||||||

| dP/dtmin, mmHg/s | −6,866 ± 319 | −5,007 ± 607 | −5,442 ± 977 | −3,967 ± 530 | −4,523 ± 936 | −3,238 ± 678 |

| EDPVR, mmHg/μl | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 |

| Tau (τ), ms | 8.6 ± 1.4 | 10.3 ± 1.0 | 10.6 ± 1.3 | 11.9 ± 1.4 | 10.9 ± 0.9 | 11.6 ± 0.5 |

LVSP and ESP were decreased significantly after TRV120023 infusion in a dose-dependent manner. EF and cardiac contractility (Ees and Emax) were also decreased in TRV120023 100 μg · kg−1 · min−1 infusion group. (

P < 0.01;

P < 0.05;

n = 5/group.) P values reflect comparisons with basal condition within the same treatment group with the use of 1-way ANOVA.

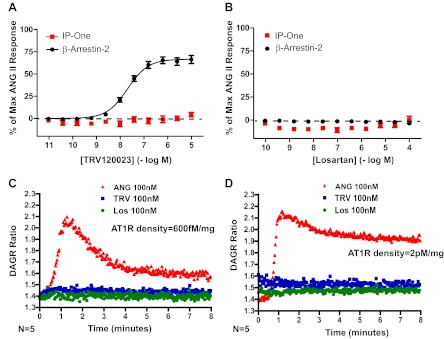

To demonstrate that TRV120023 functions as a β-arrestin-biased AT1R agonist in vitro, we tested its ability to activate signaling downstream of G-protein and β-arrestin in HEK293 cells stably overexpressing AT1R. We found that TRV120023 induces β-arrestin recruitment (EC50 = 44 nM) without activation of G-protein-coupled pathways, as measured by IP and DAG accumulation (Fig. 4, A, C, and D). Losartan has no detectable efficacy in these assays (Fig. 4, B–D). These findings are consistent with previous work showing that TRV120023 stimulation induces AT1R internalization, whereas losartan does not (32). Radioligand-binding studies using [125I]-ANG II show the inhibition constant (Ki) for TRV120023 to be 10 ± 3 nM.

Fig. 4.

Recruitment of β-arrestin-2 with TRV120023 with no activation of G-protein-mediated signaling. A: dose response of TRV120023 in human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells overexpressing ANG II type 1 receptor (AT1R) for recruitment of β-arrestin and activation of G-protein [inositol monophosphate 1 (IP-One)] reveals selective recruitment of β-arrestin. Data are mean ± SE for 15–20 independent experiments. B: dose response of losartan (Los) in HEK293 cells overexpressing AT1R reveals an absence of β-arrestin recruitment and G-protein activation. C and D: administration of TRV120023 to HEK293 cells expressing high (600 fM/mg) and very high (2 pM/mg) levels of AT1R did not result in accumulation of diacylglycerol (DAG) as revealed by the fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based DAG reporter (DAGR) (31).

AT1R-biased agonism activates prosurvival signaling following cardiac injury.

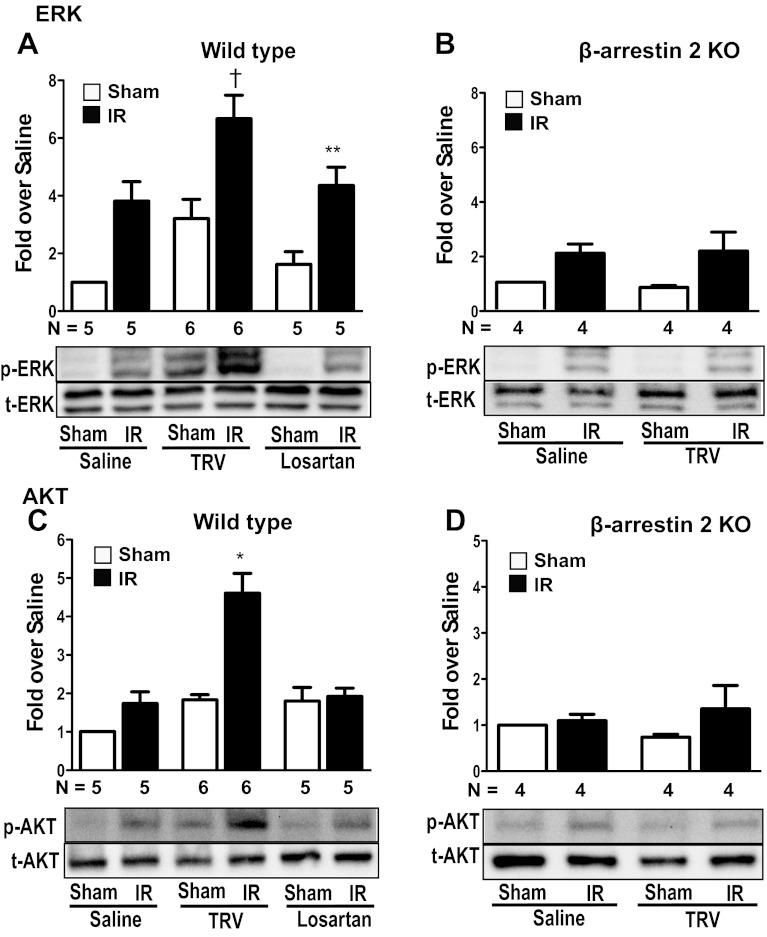

To determine whether pretreatment with TRV120023 induces cardioprotective signaling within the context of a pathologic insult, we measured the levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 and Akt in myocardial lysates harvested from WT and β-arrestin-2 KO mice after IR injury. In WT mice, pretreatment with 100 μg·kg−1·min−1 intravenous TRV120023, 30 min prior to coronary artery occlusion, significantly increased phosphorylated ERK1/2 to a greater extent compared with saline- or losartan-treated WT mice (Fig. 5A). Importantly, TRV120023 pretreatment fails to increase ERK1/2 phosphorylation after IR in β-arrestin-2 KO mice (Fig. 5B). The increase in phosphorylated Akt with TRV120023 in WT mice after IR was not observed with losartan treatment (Fig. 5C) or in TRV120023-treated β-arrestin KO mice (Fig. 5D). These findings demonstrate that pretreatment with TRV120023 enhances cardioprotective ERK1/2 and Akt signaling during IR in a β-arrestin-2-dependent fashion compared with the unbiased ARB, losartan.

Fig. 5.

TRV120023 enhances ERK1/2 and Akt signaling after ischemia reperfusion (IR). A and C: ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation were increased significantly in TRV120023-treated WT mice undergoing IR (**P < 0.05 for saline IR vs. saline Sham and losartan IR vs. losartan Sham; †P < 0.01 for saline IR vs. TRV IR; *P < 0.001 for TRV IR vs. saline and losartan IR; n = 5–6 in each group). B and D: Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation were not changed significantly in β-arrestin-2 KO mice after IR (n = 4 in each group). TRV120023 = 100 μg·kg−1·min−1 infusion; losartan = 5 mg·kg−1·min−1 infusion. p-ERK and p-AKT, phosphorylated ERK and Akt, respectively; t-ERK and t-AKT, total ERK and Akt, respectively.

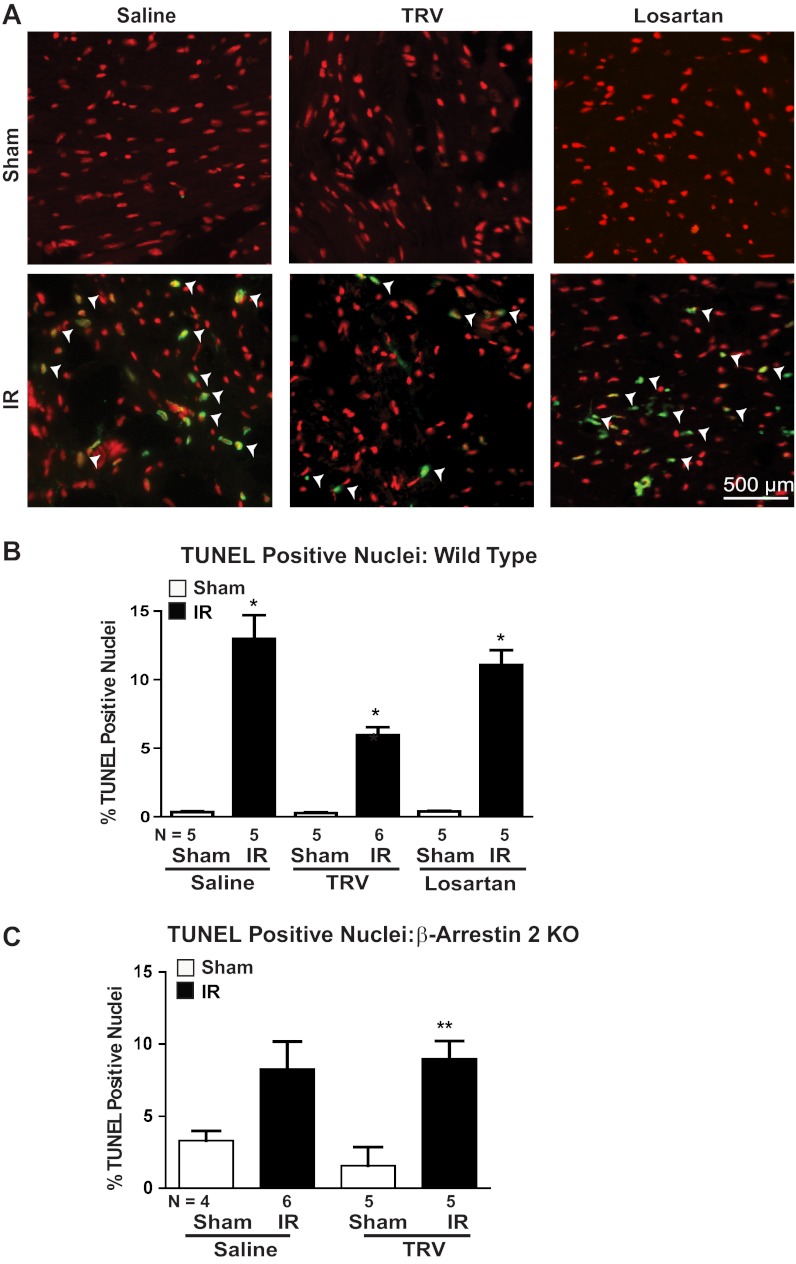

To examine whether the cardioprotective signaling induced by TRV120023 results in decreased cell death, we next tested whether TRV120023 pretreatment would decrease cardiomyocyte apoptosis after IR injury. The number of TUNEL-positive cardiomyocytes, a marker of apoptosis, was reduced significantly in TRV120023-treated animals compared with either saline or losartan (Fig. 6, A and B). Moreover, this antiapoptotic effect of TRV120023 was abrogated in β-arrestin-2 KO mice undergoing IR, indicating that the inhibition of cellular apoptosis is mediated through β-arrestin-2 (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

IR-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis was attenuated by TRV120023 pretreatment. A: representative images of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated nick end-labeling (TUNEL) staining. White arrowheads indicate TUNEL-positive nuclei (green). B: the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei was increased significantly in IR groups compared with Sham groups. TUNEL-positive nuclei were significantly attenuated in TRV120023-treated groups (*P < 0.001 for all IR vs. Sham conditions and for TRV IR vs. losartan and saline IR; n = 5–6/group). C: the antiapoptotic effect of TRV120023 was lost in β-arrestin-2 KO animals undergoing IR (**P < 0.05 for TRV Sham vs. IR condition; n = 4–6/group). TRV = 100 μg·kg−1·min−1 infusion; losartan = 5 mg·kg−1·min−1 infusion.

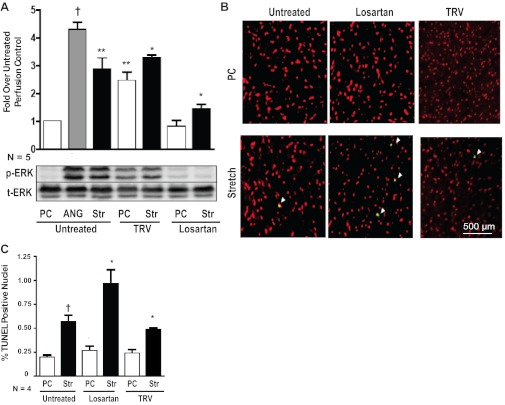

Since stretch-mediated AT1R signaling in the heart is mediated by β-arrestin-2 (22), we tested whether TRV120023 would enhance cardioprotective signaling in a model of ex vivo mechanical stretch. We perfused hearts in a Langendorff preparation and induced mechanical stretch by inflating a balloon inserted into the ventricle through the mitral valve (22). Hearts were perfused with saline, losartan, or TRV120023 for 30 min during the period of mechanical stretch. TRV120023 administration promoted a two- to threefold increase in phosphorylated ERK1/2, which was maintained during stretch (Fig. 7A). In contrast, no significant increase in phosphorylated ERK1/2 was observed in hearts perfused with losartan (Fig. 7A). Consistent with our findings of an increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation with TRV120023 treatment, the level of TUNEL-positive cells was decreased significantly in the TRV120023-treated hearts compared with those treated with losartan (Fig. 7, B and C).

Fig. 7.

TRV120023 promotes cytoprotective signaling after mechanical stretch injury. A: ERK1/2 phosphorylation was increased significantly in TRV120023-treated WT mice undergoing ex vivo balloon stretch (Str) injury compared with losartan-treated mice [†P < 0.01 for untreated perfusion control (PC) vs. ANG; **P < 0.05 for untreated PC vs. untreated Str and TRV PC; *P < 0.001 for TRV Str vs. untreated PC and losartan Str; n = 5/group]. B: representative images of TUNEL-stained histologic sections revealing diminished apoptosis in TRV120023 animals undergoing balloon stretch. White arrowheads indicate TUNEL-positive nuclei (green). C: the percent of TUNEL-positive nuclei was increased significantly in balloon-stretched “Untreated” and losartan-treated hearts compared with PC hearts (†P < 0.01 for untreated Str vs. untreated PC; *P < 0.001 for losartan Str vs. losartan PC; n = 4/group). TRV120023-treated hearts had significantly less TUNEL-positive nuclei compared with losartan-treated hearts (*P < 0.001 for TRV Str vs. losartan Str; n = 4/group).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we tested the effect of the β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligand, TRV120023, on cardiac performance and response to injury and show that: 1) stimulation with a selective β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligand increases cardiac contractility in vivo, and this effect is lost in β-arrestin-2 KO animals; 2) during in vivo cardiac injury, TRV120023 treatment enhances ERK1/2 and Akt signaling in a β-arrestin-2-dependent manner; and 3) treatment with TRV120023 promotes cell survival during cardiac injury, as assessed by TUNEL positivity compared with treatment with the unbiased ARB losartan.

Mechanism for cytoprotection by β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligands.

Ischemic myocardial injury is a clinical condition that commonly leads to the development of congestive heart failure. Thus maintenance of cell number and function following ischemic injury is an important therapeutic strategy to prevent ischemic cardiac dysfunction. It is known that ischemic injury alone results in upregulation of MAPK and Akt signaling in response to stress, although the function of kinases activated in this manner is unclear (26). The activation of ERK1/2, as observed in the saline- and losartan-treated animals undergoing IR injury (Fig. 5, A and B), is likely mediated via a non-β-arrestin pathway, potentially through PKC (7). In contrast, upregulation of these kinases via β-arrestin-mediated signaling downstream of both AT1Rs and β-adrenergic receptors has been consistently shown to be cytoprotective in both in vitro and in vivo model systems (3, 15, 22, 28). A key pathologic feature in ischemic injury is the loss of cardiomyocytes through necrosis and apoptosis. Previous work has shown that β-arrestin-mediated signaling has an antiapoptotic effect through phosphorylation and subsequent inactivation of the proapoptotic mediator Bcl-2-associated death promoter via activation of MAPK pathways (3). However, the physiologic significance of this finding was unknown. In the present study, we show that TRV120023 significantly reduces the level of apoptosis in mouse hearts subjected to IR or ventricular stretch and that this effect is β-arrestin dependent. Our data indicate that β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligands not only enhance cytoprotective signals in vivo but that this also translated to diminished cell loss. These findings are consistent with recently published ex vivo work (11) and support our hypothesis that myocyte loss due to IR or stretch injury can be pharmacologically attenuated through modulation of the AT1R and that β-arrestin-biased agonism is indeed a therapeutic strategy of significant physiologic relevance.

Role of β-arrestin-biased AT1R agonism during acute ischemic injury.

The activation of the AT1R by its endogenous ligand, ANG II, induces increased cardiac contractility, which over brief periods, is advantageous in the maintenance of cardiovascular homeostasis and organ perfusion. However, chronic activation of the AT1R results in the development and progression of cardiac dysfunction (1, 2, 5, 16, 20, 24). Ex vivo studies (21) and more recently, in vivo studies (32) have shown that β-arrestin-biased AT1R ligands enhance contractility independent of G-protein activation and that these effects translate to improvements in cardiac unloading and renal perfusion in a canine model of heart failure (8). Treatment with unbiased ARBs counteracts peripheral vasoconstriction, which is advantageous, but results in reduced cardiac contractility (10, 13, 27, 30, 32). In this study, we show that the contractility effect associated with TRV120023 is indeed β-arrestin-2 dependent, whereas its effect on blood pressure lowering is independent of β-arrestin and likely mediated by inhibiting G-protein signaling in the peripheral vasculature. These findings present intriguing implications for cardiac therapy in congestive heart failure in general and ischemic injury in particular, which is often characterized clinically by peripheral arterial vasoconstriction and diminished cardiac contractility. Indeed, TRV120027, a β-arrestin-biased peptide related to TRV120023, is currently being studied in the treatment of heart failure (http://clinicaltrials.gov; Unique Identifier NCT01187836). TRV120023 has similar potency to TRV120027 [Ki of 10 nM and 16 nM (32), respectively] and similar efficacy for β-arrestin recruitment [EC50 of 44 nM and 17 nM (32), respectively].

In our study, we found that mice treated with a β-arrestin-biased AT1R agonist show increased load-independent measures of contractility (Ees and Emax) compared with losartan. Previous work has shown that the administration of a β-arrestin-biased AT1R agonist does not increase intracellular calcium levels (21), and as we show in this study, TRV120023 does not lead to the accumulation of IP1 and DAG. We therefore hypothesize that the β-arrestin-dependent inotropic effect of TRV120023 is likely related to enhanced sensitivity of the myofilament to calcium. Interestingly, WT mice treated with losartan showed reduced contractility, which may represent the combined effect of inhibiting both G-protein-mediated signaling and β-arrestin-dependent inotropic effects on cardiac function. This assertion is supported by the finding that TRV120023 decreases contractility (Ees and Emax) and functional measures (ejection fraction) in β-arrestin-2 KO mice through the combined reduction of circulating ANG II-induced G-protein/β-arrestin-mediated inotropy. Interestingly, saline infusion alone depressed contractility in β-arrestin-2 KO mice (Fig. 3, B and C). We hypothesize that this finding may be related to alterations in length-dependent force generation in the β-arrestin-2 KO mice. Further studies investigating the role of myofilament sensitivity as a mechanism for the observed β-arrestin-mediated inotropic effect will need to be performed.

In conclusion, we show that a selective β-arrestin-biased AT1R agonist enhances contractility and promotes cardiomyocyte survival during acute cardiac injury of IR and mechanical stretch.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL56687 and HL75443 to H. A. Rockman.

DISCLOSURES

H. A. Rockman is a scientific cofounder of Trevena, a company that is developing G-protein-coupled receptor-targeted drugs.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K-S.K., D.M.A., and H.A.R. conception and design of research; K-S.K., D.M.A., B.W., and L.M. performed experiments; K-S.K. and D.M.A. analyzed data; K-S.K., D.M.A., and H.A.R interpreted results of experiments; K-S.K., D.M.A., and J.D.V. prepared figures; K-S.K. and D.M.A. drafted manuscript; K-S.K., D.M.A, J.D.V., and H.A.R. edited and revised manuscript; K-S.K., D.M.A., B.W., J.D.V., L.M., and H.A.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address of K-S. Kim: Dept. of Medicine, College of Medicine, Jeju National Univ., 1573-3 Ara 1 dong, Jeju-si, Jeju Special Self-Governing Province, 690-716, South Korea.

REFERENCES

- 1. Effect of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. The SOLVD Investigators. N Engl J Med 327: 685–691, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. The SOLVD Investigators. N Engl J Med 325: 293–302, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahn S, Kim J, Hara MR, Ren XR, Lefkowitz RJ. {beta}-Arrestin-2 mediates anti-apoptotic signaling through regulation of BAD phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 284: 8855–8865, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahn S, Shenoy SK, Wei H, Lefkowitz RJ. Differential kinetic and spatial patterns of beta-arrestin and G protein-mediated ERK1/2 activation by the angiotensin II receptor. J Biol Chem 279: 35518–35525, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ainscough JF, Drinkhill MJ, Sedo A, Turner NA, Brooke DA, Balmforth AJ, Ball SG. Angiotensin II type-1 receptor activation in the adult heart causes blood pressure-independent hypertrophy and cardiac dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res 81: 592–600, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aplin M, Christensen GL, Schneider M, Heydorn A, Gammeltoft S, Kjolbye AL, Sheikh SP, Hansen JL. The angiotensin type 1 receptor activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 by G protein-dependent and -independent pathways in cardiac myocytes and Langendorff-perfused hearts. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 100: 289–295, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Armstrong SC. Protein kinase activation and myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res 61: 427–436, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boerrigter G, Lark MW, Whalen EJ, Soergel DG, Violin JD, Burnett JC., Jr Cardiorenal actions of TRV120027, a novel β-arrestin-biased ligand at the angiotensin II type I receptor, in healthy and heart failure canines: a novel therapeutic strategy for acute heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 4: 770–778, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Peppel K, Caron MG, Lin FT. Enhanced morphine analgesia in mice lacking beta-arrestin 2. Science 286: 2495–2498, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gonzalez GE, Seropian IM, Krieger ML, Palleiro J, Lopez Verrilli MA, Gironacci MM, Cavallero S, Wilensky L, Tomasi VH, Gelpi RJ, Morales C. Effect of early versus late AT(1) receptor blockade with losartan on postmyocardial infarction ventricular remodeling in rabbits. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H375–H386, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hostrup A, Christensen GL, Bentzen BH, Liang B, Aplin M, Grunnet M, Hansen JL, Jespersen T. Functionally selective AT(1) receptor activation reduces ischemia reperfusion injury. Cell Physiol Biochem 30: 642–652, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim J, Ahn S, Rajagopal K, Lefkowitz RJ. Independent beta-arrestin2 and Gq/protein kinase Czeta pathways for ERK1/2 stimulated by angiotensin type 1A receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells converge on transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem 284: 11953–11962, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koifman B, Topilski I, Megidish R, Zelmanovich L, Chernihovsky T, Bykhovsy E, Keren G. Effects of losartan + L-arginine on nitric oxide production, endothelial cell function, and hemodynamic variables in patients with heart failure secondary to coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 98: 172–177, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lima B, Lam GK, Xie L, Diesen DL, Villamizar N, Nienaber J, Messina E, Bowles D, Kontos CD, Hare JM, Stamler JS, Rockman HA. Endogenous S-nitrosothiols protect against myocardial injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 6297–6302, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Noma T, Lemaire A, Naga Prasad SV, Barki-Harrington L, Tilley DG, Chen J, Le Corvoisier P, Violin JD, Wei H, Lefkowitz RJ, Rockman HA. beta-Arrestin-mediated beta1-adrenergic receptor transactivation of the EGFR confers cardioprotection. J Clin Invest 117: 2445–2458, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paradis P, Dali-Youcef N, Paradis FW, Thibault G, Nemer M. Overexpression of angiotensin II type I receptor in cardiomyocytes induces cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 931–936, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Patel CB, Noor N, Rockman HA. Functional selectivity in adrenergic and angiotensin signaling systems. Mol Pharmacol 78: 983–992, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perrino C, Naga Prasad SV, Mao L, Noma T, Yan Z, Kim HS, Smithies O, Rockman HA. Intermittent pressure overload triggers hypertrophy-independent cardiac dysfunction and vascular rarefaction. J Clin Invest 116: 1547–1560, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Yusuf S, Pocock S. Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme. Lancet 362: 759–766, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rajagopal K, Whalen EJ, Violin JD, Stiber JA, Rosenberg PB, Premont RT, Coffman TM, Rockman HA, Lefkowitz RJ. beta-Arrestin2-mediated inotropic effects of the angiotensin II type 1A receptor in isolated cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 16284–16289, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rakesh K, Yoo B, Kim IM, Salazar N, Kim KS, Rockman HA. beta-Arrestin-biased agonism of the angiotensin receptor induced by mechanical stress. Sci Signal 3: ra46, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reiter E, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Lefkowitz RJ. Molecular mechanism of beta-arrestin-biased agonism at seven-transmembrane receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 52: 179–197, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rengo G, Lymperopoulos A, Koch WJ. Future G protein-coupled receptor targets for treatment of heart failure. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 11: 328–338, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rockman HA, Koch WJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane-spanning receptors and heart function. Nature 415: 206–212, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rose BA, Force T, Wang Y. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the heart: angels versus demons in a heart-breaking tale. Physiol Rev 90: 1507–1546, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sladek T, Sladkova J, Kolar F, Papousek F, Cicutti N, Korecky B, Rakusan K. The effect of AT1 receptor antagonist on chronic cardiac response to coronary artery ligation in rats. Cardiovasc Res 31: 568–576, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Song JQ, Teng X, Cai Y, Tang CS, Qi YF. Activation of Akt/GSK-3beta signaling pathway is involved in intermedin(1-53) protection against myocardial apoptosis induced by ischemia/reperfusion. Apoptosis 14: 1299–1307, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Strauss MH, Hall AS. Angiotensin receptor blockers may increase risk of myocardial infarction: unraveling the ARB-MI paradox. Circulation 114: 838–854, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thai HM, Van HT, Gaballa MA, Goldman S, Raya TE. Effects of AT1 receptor blockade after myocardial infarct on myocardial fibrosis, stiffness, and contractility. Am J Physiol 276: H873–H880, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Violin JD, Dewire SM, Barnes WG, Lefkowitz RJ. G protein-coupled receptor kinase and beta-arrestin-mediated desensitization of the angiotensin II type 1A receptor elucidated by diacylglycerol dynamics. J Biol Chem 281: 36411–36419, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Violin JD, DeWire SM, Yamashita D, Rominger DH, Nguyen L, Schiller K, Whalen EJ, Gowen M, Lark MW. Selectively engaging beta-arrestins at the angiotensin II type 1 receptor reduces blood pressure and increases cardiac performance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 335: 572–579, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wei H, Ahn S, Shenoy SK, Karnik SS, Hunyady L, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Independent beta-arrestin 2 and G protein-mediated pathways for angiotensin II activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 10782–10787, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yoo B, Lemaire A, Mangmool S, Wolf MJ, Curcio A, Mao L, Rockman HA. beta1-Adrenergic receptors stimulate cardiac contractility and CaMKII activation in vivo and enhance cardiac dysfunction following myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1377–H1386, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]