Abstract

In cat atrial myocytes, β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) stimulation exerts profound effects on excitation-contraction coupling and cellular Ca2+ cycling that are mediated by β1- and β2-AR subtypes coupled to G proteins (Gs and Gi). In this study, we determined the effects of β-AR stimulation on pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans. Ca2+ alternans was recorded from single cat atrial myocytes with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator indo-1. Stable Ca2+ alternans occurred at an average pacing frequency of 1.7 Hz at room temperature with a mean alternans ratio of 0.43. Nonselective β-AR stimulation as well as selective stimulation of β1/Gs, β2/Gs + Gi, and β2/Gs coupled pathways all abolished pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans. β1-AR stimulation abolished alternans through stimulation of PKA and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, whereas β2-AR stimulation exclusively involved PKA and was mediated via Gs, whereas a known second pathway in cat atrial myocytes acting through Gi and nitric oxide production was not involved in alternans regulation. Inhibition of various mitochondrial functions (dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential or inhibition of mitochondrial F1/F0-ATP synthase, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake via the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter, and Ca2+ extrusion via mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchange) enhanced Ca2+ alternans; however, β-AR stimulation still abrogated alternans, provided that sufficient cellular ATP was available. Selective inhibition of mitochondrial or glycolytic ATP production did not prevent β-AR stimulation from abolishing Ca2+ alternans. However, when both ATP sources were depleted, β-AR stimulation failed to decrease Ca2+ alternans. These results indicate that in atrial myocytes, β-AR stimulation protects against pacing-induced alternans by acting through parallel and complementary signaling pathways.

Keywords: arrhythmia, β-adrenergic signaling, cardiac calcium alternans, energy metabolism, intracellular calcium, mitochondria

cardiac alternans is defined as a beat-to-beat alternation in contraction amplitude (mechanical alternans), action potential duration (electrical or action potential duration alternans), and Ca2+ transient amplitude (Ca2+ alternans) at a constant stimulation frequency (e.g., Ref. 57). Alternans has been recognized as a risk factor for cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death (47–49), including atrial fibrillation (20, 37), and although it is considered a multifactorial process, it has become increasingly clear that alternans is ultimately linked to disturbances in myocardial Ca2+ homeostasis and impaired intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) regulation (for reviews, see Refs. 5, 6, 12–14, 16, 31, 36, and 43). Based on the theory of cardiac Ca2+ signaling, computational studies, and experimental data (for reviews and references, see Refs. 54 and 56), two parameters have emerged as critically relevant to the generation of alternans at the cellular level: fractional Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), dependent on SR load, and the efficiency of beat-to-beat cytosolic Ca2+ sequestration. Ca2+ sequestration depends on the availability of adequate ATP supplies to fuel Ca2+ pumps [particularly sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA)] and to serve as a substrate for phosphorylation processes as well as on organelles capable of storing Ca2+. We have previously shown that conditions that are accompanied by reduced ATP generation promote the generation of alternans. Our previous studies showed that inhibition of glycolysis (5, 23, 28, 29) as well as mitochondrial function (16) enhances the propensity of electromechanical and Ca2+ alternans in atrial myocytes.

Sympathetic innervation of the heart elicits chronotropic, inotropic, and lusitropic effects that facilitate an increase in cardiac output and are mediated by β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) signaling (46). At the level of cardiomyocytes, catecholamine binding to β-ARs causes an increase in cellular Ca2+ cycling that associates with the phosphorylation of Ca2+-handling proteins by cellular kinases such as PKA and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). Due to the profound influence of β-AR signaling on cardiac Ca2+ cycling and excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling, it is not all surprising that β-AR stimulation also affects cardiac alternans (14, 15). In clinical settings, for example, administration of antiadrenergic drugs (β-blockers) has been shown to reduce microvolt-level T-wave alternans (e.g., Refs. 26 and 27), an established marker of susceptibility to sudden cardiac death (44, 49). However, the relationship between β-AR signaling and alternans is not straightforward, and opposite effects have been observed, in which β-AR stimulation either favors (7, 39) or protects (11, 23, 24) against alternans and alternans-related arrhythmias. At the cellular level, whether β-AR stimulation facilitates or protects against alternans critically depends on whether a β-AR stimulation-mediated increase in SR load and fractional release (favoring alternans) dominates over β-AR-mediated effects on Ca2+ sequestration (abolishing alternans) or vice versa.

We have previously shown that in cat atrial myocytes, β-AR signaling is mediated by β1- and β2-AR subtypes. While β1-AR-mediated effects on E-C coupling are mediated by Gs proteins coupled to adenylate cyclase (AC), which activates cAMP-dependent PKA, β2-ARs couple to both Gs and Gi proteins (25, 60, 61). In previous studies (10, 51) of β2-AR signaling pathways responsible for the regulation of Ca2+ and K+ currents in cat atrial myocytes, we established that β2/Gs signaling acts via cAMP/PKA, similar to β1/Gs signaling. In contrast, β2/Gi signaling couples via phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt to endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS) and leads to NO production. We further established that in atrial myocytes, NO has two important downstream effects: 1) NO-dependent activation of guanylate cyclase leads to an increase of cGMP and inhibition of cGMP-dependent phosphodiesterase (PDE) III, resulting in enhanced cAMP/PKA signaling (52), and 2) NO can inhibit the β2/Gs/cAMP/PKA pathway via protein nitrosylation (10). Thus, the goal of the present study was to elucidate the interplay between these specific β-AR signaling pathways and their downstream targets, mitochondrial function, and cellular energy (ATP) sources for the regulation of pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans in atrial myocytes.

METHODS

Chemicals and solutions.

Chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted. ICI-118,551 was from AstraZeneca (Wilmington, DE), CGP-37157 was obtained from Tocris (Ellisville, MO), and KN-92, KN-93, spermine NONO-ate (SNO), and W-7 were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). During experiments, cells were continuously superfused with standard Tyrode solution containing (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, and 2 CaCl2 (pH 7.3 adjusted with NaOH). All inhibitors, agonists, and antagonists were added to normal Tyrode solution from stock solutions.

β-AR stimulation protocols.

Four different β-AR stimulation protocols were used based on our previous studies (10, 51) on β-AR signaling in cat atrial myocytes. Nonselective β1/β2-AR stimulation (termed here β-AR stimulation) was achieved with isoproterenol (ISO; 0.1 μM). For specific stimulation of β1-AR-dependent signaling (β1-AR stimulation), cells were treated with ISO (0.1 μM) in combination with the β2-AR subtype blocker ICI-118,551 (0.01 μM). Simultaneous activation of β2/Gi and β2/Gs signaling (β2-AR stimulation) was achieved with the combination of ISO (0.1 μM) and the specific β1-AR inhibitor atenolol (0.01 μM), whereas for selective β2/Gs stimulation, fenoterol (41, 42) was used (0.1 μM). Concentrations were chosen based on our previous studies (10, 51) on β-AR signaling in cat atrial myocytes.

Myocyte isolation.

Cat atrial myocytes were isolated according to previously described methods (58). All protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Adult cats of either sex were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg), and hearts were excised, mounted on a Langendorff apparatus, and retrogradely perfused with oxygenated collagenase-containing solution (37°C).

[Ca2+]i measurements.

For [Ca2+]i measurements, atrial myocytes were loaded with the membrane-permeable form of the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator indo-1 AM (5 μM, Invitrogen/Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) in standard Tyrode solution for 15–20 min at room temperature followed by a >20-min deesterification interval in dye-free media. Indo-1-loaded cells were excited at 360 nm, and emission signals were collected simultaneously at 410-nm fluorescence (F410) and 485-nm fluorescence (F485) using photomultiplier tubes. Fluorescence signals were background subtracted, and [Ca2+]i changes are expressed as changes in the ratio (R) of F410 to F485. Ca2+ transients and Ca2+ alternans were elicited by electrical field stimulation (voltage set at ∼50% above the threshold for contraction to ensure that every electrical stimulus was captured by the myocyte) using a pair of platinum electrodes. Pacing-induced stable Ca2+ alternans was elicited by increasing the stimulation frequency from 0.5 to 1 Hz followed by further increases in stimulation frequency in 0.1-Hz increments until stable alternans was observed. Experimental protocols were applied when individual cells revealed stable alternans for ∼1 min at a given stimulation frequency. The degree of Ca2+ alternans was quantified as the alternans ratio. The alternans ratio was defined as 1 − S/L, where S/L is the ratio of the small-amplitude (S) to large-amplitude (L) Ca2+ transient during a pair of alternating Ca2+ transients (28, 59). Thus, the alternans ratio had values between 1 and 0, with 0 indicating no alternans and 1 indicating the highest possible degree of alternans, with only every other stimulation resulting in a measurable Ca2+ transient.

Temperature.

All experiments were performed at room temperature (22–25°C). The pacing frequency threshold for the occurecnce of alternans decreases with lower temperatures (14, 23). By conducting experiments at room temperature, alternans could be studied in isolated myocytes with pacing protocols that were significantly less stressful, allowing for prolonged stimulation protocols and extended cell viability over time.

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SE for the indicated number of cells (n). Statistical differences were determined using Student's t-tests for paired or unpaired data. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of β-adrenergic stimulation on pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans.

Stable Ca2+ alternans was induced by incrementally increasing the pacing frequency. Ca2+ alternans was observed at stimulation frequencies of >1 Hz. The average pacing frequency where stable maintained alternans was observed in cat atrial myocytes at room temperature was 1.7 Hz. The average alternans ratio was 0.43 ± 0.02 under control conditions.

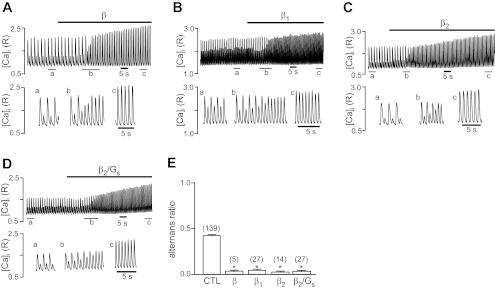

In the heart, β-AR stimulation exerts positive inotropic effects and enhances the efficacy of E-C coupling through the regulation of intracellular Ca2+-handling proteins and Ca2+ signaling pathways. Stimulation of atrial myocytes revealing stable pacing-induce Ca2+ alternans with the nonselective β-AR agonist ISO (0.1 μM) abolished alternans (alternans ratio decreased from 0.43 ± 0.02 to 0.03 ± 0.01), as shown in Fig. 1A. Furthermore, ISO increased the Ca2+ transient amplitude of both the small and large alternans Ca2+ transient by 232% and 85%, respectively, indicative of the positive inotropic effect of β-AR stimulation.

Fig. 1.

Effects of β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) stimulation on pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans. Pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans recordings are from individual atrial myocytes before and during β-AR stimulation. A: nonselective β-AR stimulation with isoproterenol (ISO; 0.1 μM). B: β1-AR-specific stimulation using ISO (0.1 μM) combined with the β2-AR antagonist ICI-118,551 (0.01 μM). C: β2-AR-specific stimulation with ISO (0.1 μM) combined with the β1-AR antagonist atenolol (0.01 μM). D: specific stimulation of the β2/Gs pathway with fenoterol (0.1 μM). Bottom recordings show Ca2+ transients at expanded times (a, b, and c) from the top recordings. E: summary of selective and nonselective β-AR stimulation on alternans ratio. Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of individual atrial myocytes tested. *P < 0.001 vs. control (CTL).

While cat atrial myocytes have both β1- and β2-subtypes of the AR (53), our previous study (51) revealed that the β3-subtype is not involved in E-C coupling regulation in cat atrial tissue. Therefore, in the following experiments, we focused on β1- and β2-AR-mediated signaling pathways. As shown in Fig. 1B, selective stimulation of the β1-AR pathway by the combined application of ISO (0.1 μM) and the β2-AR blocker ICI-118,551 (0.01 μM) abolished Ca2+ alternans to the same degree as ISO alone. Similarly, selective stimulation of the β2-AR pathway [with ISO in the presence of the β1-AR blocker atenolol (0.01 μM)] or exclusively of the β2/Gs pathway [with the selective β2/Gs agonist fenoterol (0.1 μM)] abolished Ca2+ alternans, as shown in Fig. 1, C and D, respectively. Similar to nonselective β-AR stimulation, the selective activation of β1- and β2-ARs had a positive inotropic effect on the Ca2+ transient amplitude. Thus, the combined or selective activation of β-AR subtypes leads to an abolishment of pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans. With all four stimulation protocols, the ARs dropped to similarly low values between 0.03 and 0.04 (Fig. 1E), indicative of the complete absence of Ca2+ alternans.

β-AR effects on Ca2+ alternans involves PKA.

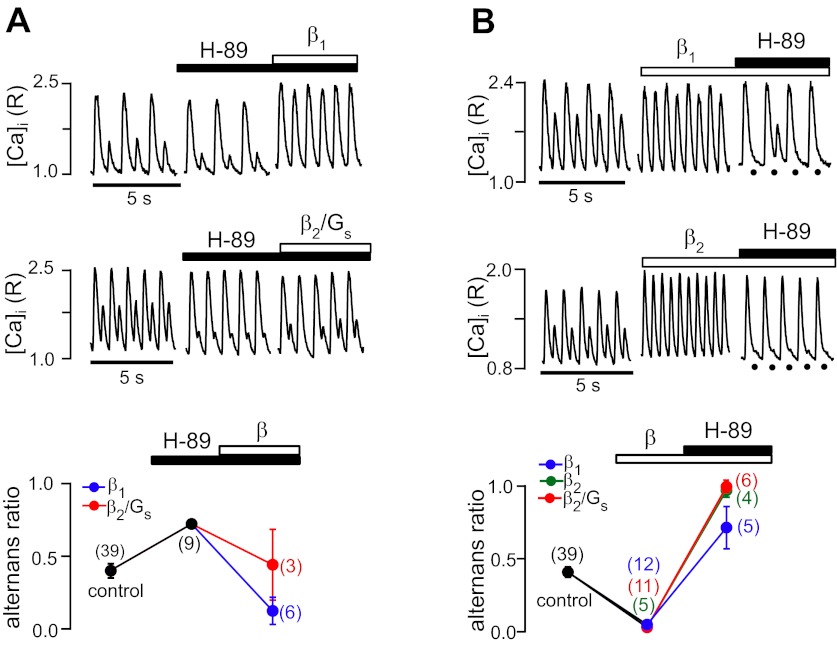

It is well established that β1- and β2-AR-mediated effects on E-C coupling are mediated by Gs proteins coupled to AC, which generates cAMP, which, in turn, activates PKA. PKA is involved in the phosphorylation processes of Ca2+-handling proteins [L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (LTCC), SERCA, and the ryanodine receptor (RyR) Ca2+-release channel], which profoundly affects Ca2+ signaling during E-C coupling. We therefore tested the effect of PKA inhibition alone and in combination with β-AR stimulation on Ca2+ alternans. As shown in Fig. 2A, the PKA inhibitor H-89 (1 μM) enhanced Ca2+ alternans and increased the alternans ratio by 76%, to 0.72 ± 0.06. These data suggest that basal PKA activity exerts partial protection against alternans. Subsequent β-AR stimulation in the presence of the PKA blocker decreased Ca2+ alternans, but with different efficiency depending on which β-AR subtype was activated. β1-AR stimulation completely abolished Ca2+ alternans (Fig. 2A, top), whereas selective activation of the β2/Gs pathway, while showing a partial decrease of alternans, failed to lower the alternans ratio below control levels (Fig. 2A, middle). The summary data of changes of the alternans ratio are shown in Fig. 2A, bottom.

Fig. 2.

β-AR effects on Ca2+ alternans mediated by PKA. A, top and middle: recordings of Ca2+ alternans before and during inhibition of PKA with H-89 (1 μM) followed by β1-AR (top) or β2/Gs stimulation (middle). Bottom, average alternans ratios in the presence of H-89 and during subsequent β1-AR and β2/Gs stimulation. B, top: recordings of Ca2+ alternans where cells were first exposed to β-AR stimulation followed by treatment with H-89 (10 μM). Bottom, average alternans ratios. During β2-AR stimulation, H-89 caused the maximal degree of alternans, with the alternans ratio approaching 1. Black circles mark the timing of electrical stimulation when the small-amplitude Ca2+ transient was strongly reduced in amplitude. Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of individual atrial myocytes tested. [Ca2+]i, intracellular Ca2+ concentration; R, ratio of fluorescence at 410 nm to fluorescence at 485 nm.

The effect of PKA inhibition was tested with a different protocol, as shown in Fig. 2B. Here, β-AR stimulation preceded the application of the PKA inhibitor. As expected, β1-AR, β2-AR, and selective β2/Gs stimulation completely abolished Ca2+ alternans. Subsequent application of H-89 (10 μM) caused the maximal degree of alternans during β2-AR stimulation, with an alternans ratio approaching 1. In contrast, during β1-AR stimulation, PKA inhibition also enhanced Ca2+ alternans beyond control levels (alternans ratio: 0.72 ± 0.15); however, the effect was less pronounced than during β2-AR stimulation. Taken together, these data indicate that β2-AR stimulation abolished alternans through a PKA-dependent pathway, whereas the decrease of alternans mediated by β1-AR signaling appeared only partially be dependent on PKA. CaMKII is a second crucial intracellular kinase that regulates Ca2+-handling proteins through phosphorylation, and it has been shown that in the heart, β1-AR stimulation activates a dual signaling pathway mediated by cAMP/PKA and CaMKII (50). Therefore, in the following set of experiments, we tested the involvement of CaMKII in β-AR-mediated regulation of Ca2+ alternans.

Role of calmodulin and CaMKII in the regulation of Ca2+ alternans.

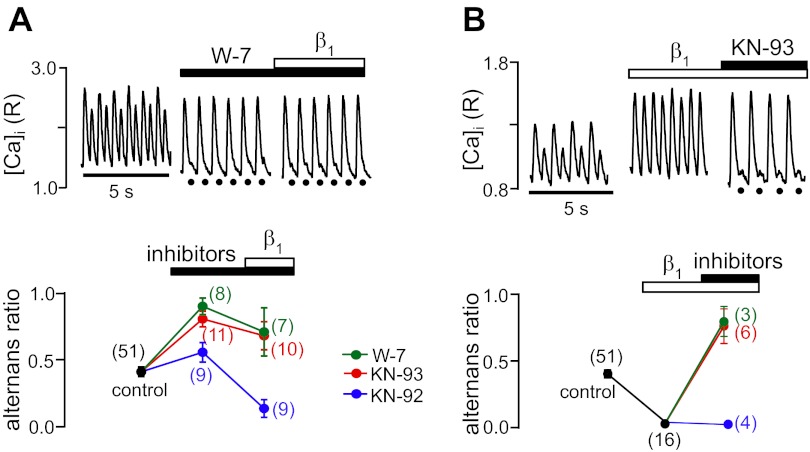

Inhibition of the CaMKII signaling pathway on pacing-induced Ca alternans is shown in Fig. 3. Exposure to the calmodulin antagonist W-7 (25 μM) led to a profound enhancement of Ca2+ alternans, again suggesting that basal kinase activity protects against the development of a high degree of alternans. In the example shown in Fig. 3A, top, W-7 almost completely abolished the small-amplitude alternans Ca2+ transient, and, on average, the alternans ratio increased to 0.90 ± 0.05. Similarly, the CaMKII antagonist KN-93 (1 μM) enhanced Ca2+ alternans and increased the alternans ratio to 0.77 ± 0.06 (Fig. 3A, bottom), whereas KN-92, the inactive analog of KN-93, serving as a negative control, had only a marginal effect on the alternans ratio. Subsequent β1-AR stimulation decreased Ca2+ alternans, but in the presence of W-7 and KN-93, the alternans ratio remained above control levels (0.69 ± 0.18 and 0.67 ± 0.10, respectively). In contrast, in the presence of the inactive analog KN-92, β1-AR stimulation was capable of completely abolishing Ca2+ alternans.

Fig. 3.

β-AR effects on Ca2+ alternans mediated by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). A, top: recordings of Ca2+ alternans before and during inhibition of calmodulin with W-7 (25 μM) followed by β1-AR stimulation. Bottom, average alternans ratios in the presence of W-7, the CaMKII inhibitor KN-93 (1 μM), or the inactive analog KN-92 (1 μM) followed by β1-AR stimulation. B, top: decrease of Ca2+ alternans by β1-AR stimulation was reversed and alternans was enhanced by subsequent treatment with KN-93. Bottom, average alternans ratios during β1-AR stimulation followed by treatment with W-7, KN-93, or KN-92. KN-92, the inactive analog of KN-93, served as a negative control. Black circles mark the timing of electrical stimulation when the small-amplitude Ca2+ transient was strongly reduced in amplitude. Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of individual atrial myocytes tested.

Figure 3B shows the reversed protocol. β1-AR stimulation abolished pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans, as expected; however, the subsequent application of W-7 and KN-93 increased the alternans ratio above control levels, to 0.78 ± 0.11 and 0.76 ± 0.13, respectively. The inactive analog KN-92 had no influence on the abolishing effect of β1-AR stimulation (Fig. 3B, bottom). These data indicate that the effect of β1-AR stimulation to abolish alternans largely depends on CaMKII activity and, to a lesser extent, on the cAMP/PKA pathway, whereas the β2-AR-dependent effects on Ca2+ alternans primarily involve PKA. This was further confirmed by the observation that in the presence of KN-93, β2-AR stimulation still lowered the alternans ratio below control levels (data not shown).

Combined inhibition of PKA and CaMKII is required to abolish β1-AR effects on Ca2+ alternans.

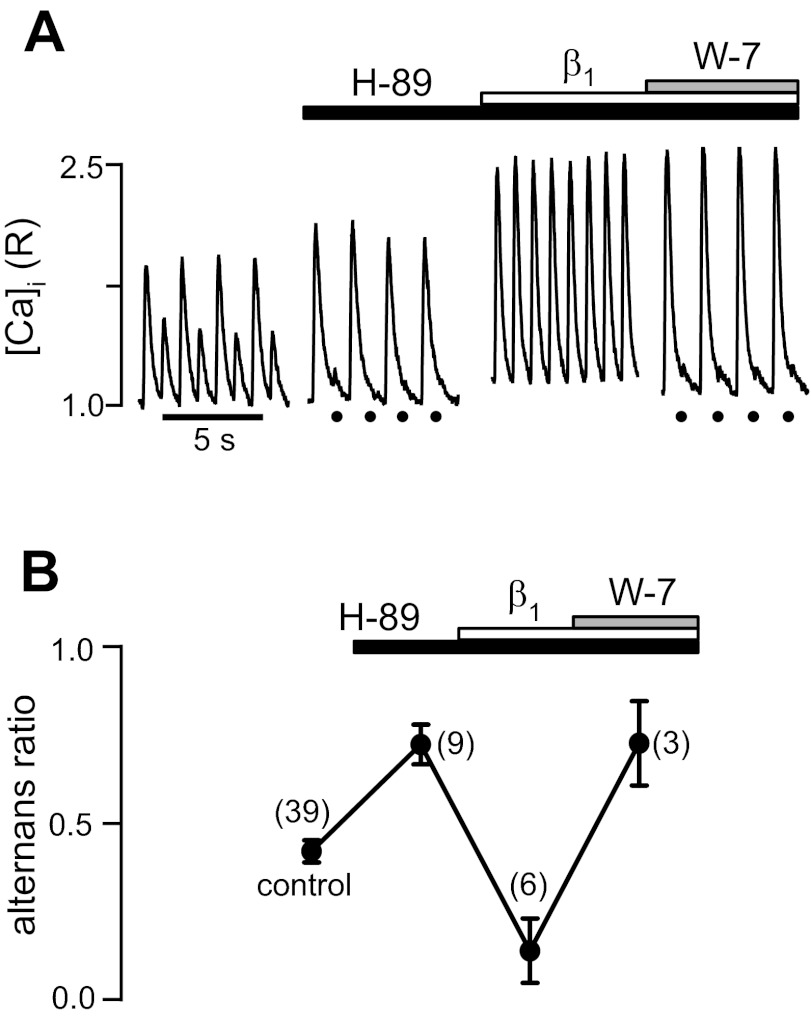

After pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans was enhanced by the inhibition of PKA (alternans ratio in the presence of H-89: 0.72 ± 0.06; Fig. 4), subsequent β1-AR stimulation reversed the effect of H-89 and decreased the alternans ratio below control levels (alternans ratio: 0.13 ± 0.09). Subsequent exposure to W-7 reversed the effect of β1-AR stimulation. In the example shown in Fig. 4, top, combined inhibition of PKA and CaMKII almost completely abolished the small-amplitude Ca2+ transient despite β1-AR stimulation. On average, the alternans ratio rose to 0.72 ± 0.12. In conclusion, the results indicate that β1-AR stimulation protects against alternans by invoking two complementary signaling pathways, one involving cAMP/PKA and the other depending on CaMKII activity.

Fig. 4.

β1-AR effects on Ca2+ alternans are mediated by both PKA and CaMKII. A: Ca2+ transient recordings revealing Ca2+ alternans from an atrial myocyte subsequently treated with the PKA inhibitor H-89 followed by β1-AR stimulation and the subsequent addition of W-7. B: average alternans ratios. The data indicate that during combined inhibition of PKA and CaMKII, β1-AR failed to decrease Ca2+ alternans. Black circles mark the electrical stimulation when the small-amplitude Ca2+ transient was strongly reduced in amplitude. Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of individual atrial myocytes tested.

Role of downstream targets of β2-AR signaling in the protection against alternans.

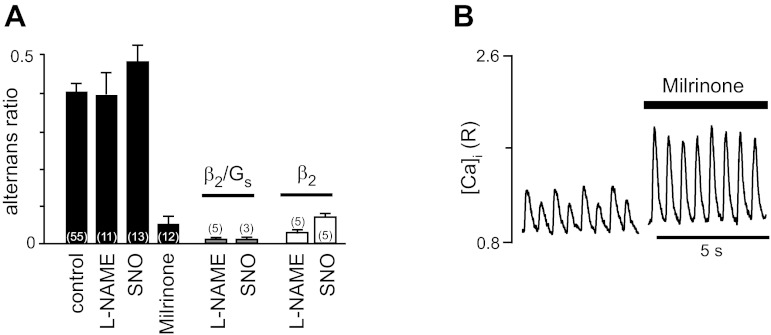

β2-ARs couple to both Gs and Gi proteins (25, 60, 61). As detailed in the Introduction, in cat atrial myocytes, the β2/Gi signaling pathway couples via PI3K/Akt to eNOS and leads to NO production. The downstream effects of NO are twofold and result in enhanced cAMP/PKA signaling via inhibition of cGMP-dependent PDE III but also inhibition of the β2/Gs/AC/cAMP/PKA pathway (1, 10). Since NO plays a key role in the β2/Gi signaling pathways, we applied a blocker of eNOS [Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME)] or supplied NO in excess with an exogenous NO donor (SNO). As shown in Fig. 5A, neither l-NAME nor SNO had a profound effect on the alternans ratio of pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans. Selective stimulation of the β2/Gs pathway in the presence of l-NAME or SNO resulted in a complete abolishment of Ca2+ alternans, suggesting that the β2/Gs pathway is sufficient for complete protection against alternans during β2-AR stimulation. Concomitant stimulation of the β2/Gi pathway had no additional effect, indicating that the β2/Gi pathway (and thus NO) does not play a significant role in the regulation of alternans. This was further confirmed by the observation that in the presence of pertussis toxin to disrupt Gi regulation (61), β2/Gs stimulation fully abolished alternans (data not shown) and that even in the presence of excessive amounts of NO, β2-AR stimulation led to an abrogation of alternans (Fig. 5A). In addition, inhibition of PDE III by milrinone (Fig. 5B) completely abolished Ca2+ alternans and had a strong positive inotropic effect on the Ca2+ transient amplitude, presumably by increasing cytosolic cAMP levels. β2-AR stimulation in the presence of milrinone had no additional effect on the alternans ratio since the alternans ratio was already nearly 0 (data not shown). In conclusion, these data indicate that β2-AR-mediated abolishment of Ca2+ alternans is mediated by the β2/Gs/AC/cAMP/PKA pathway.

Fig. 5.

Effects of nitric oxide (NO) and phosphodiesterase (PDE) on Ca2+ alternans. A: average alternans ratios under control conditions and in the presence of the endothelial NO synthase inhibitor Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME; 50 μM), the exogenous NO donor spermine NONOate (SNO; 100 μM), and the PDE III inhibitor milrinone (5 μM) (solid bars). Shaded and open bars show the effects of l-NAME and SNO on alternans ratios during specific β2/Gs and nonselective β2-AR stimulation, respectively. B: recordings of pacing-induced Ca2+ transients followed by treatment with milrinone. Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of individual atrial myocytes tested.

Under β-AR stimulation, normal contraction of myocytes and intracellular Ca2+ cycling are critically dependent on the balance between myocardial energy demand and energy supply from mitochondrial and glycolytic sources. Thus, in the next experiments, we explored the role of β-AR signaling in Ca2+ alternans during metabolic inhibition.

Alternans depends on the interaction between mitochondrial function and β-AR signaling.

We have previously shown that inhibition of various mitochondrial functions (ranging from inhibition of the electron transport chain, F1/F0-ATP synthase, and mitochondrial dehydrogenases to mitochondrial Ca2+ transport) enhances the propensity and degree of Ca2+ alternans, suggesting that mitochondrial function, specifically ATP production, plays a critical role in the generation of alternans (16).

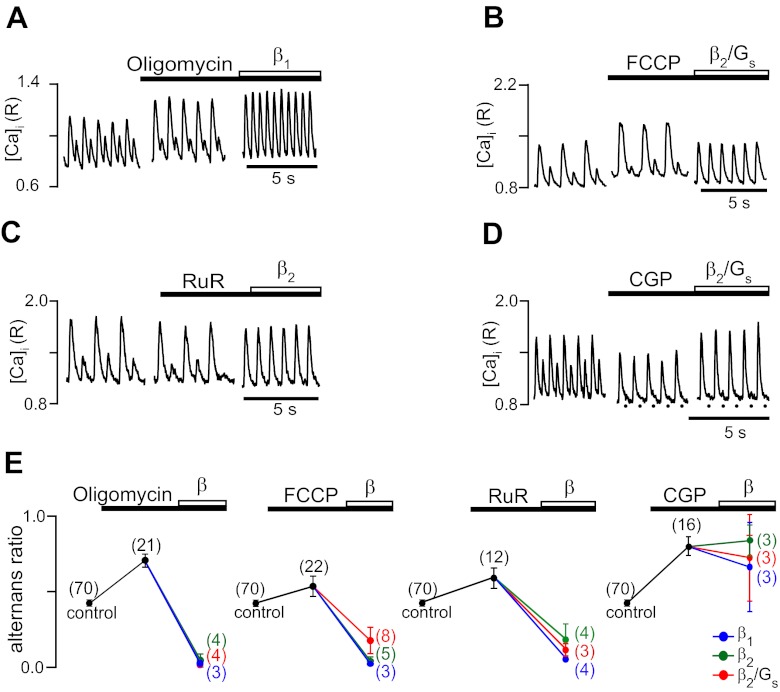

Consistent with our previous study, as shown in Fig. 6, inhibition of mitochondrial ATP production by block of mitochondrial F1/F0-ATP synthase with oligomycin (A), dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential with FCCP (B), inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake via the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter with ruthenium red (C), or Ca2+ extrusion via the mitochondrial Na+/ Ca2+ exchanger with CGP-37157 (D) all enhanced Ca2+ alternans and increased the alternans ratio to values between 0.53 and 0.80 (E). β-AR stimulation in the presence of oligomycin, FCCP, or ruthenium red lowered the alternans ratio and decreased and even abolished alternans. There were no significant differences between β1- and β2-AR-mediated signaling. In contrast, β-AR stimulation after the inhibition of Ca2+ extrusion with CGP-37157 failed to significantly decrease alternans. We (16) have previously shown that treatment with CGP-37157 led to cyclosporine-sensitive opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), which is linked to irreversible impairment of mitochondrial function. Presumably due to the irreversible nature of MPTP opening, β-AR stimulation failed to protect against Ca2+ alternans. In contrast, these results indicate that potentially reversible inhibition of mitochondrial functions can be counteracted through β-AR signaling.

Fig. 6.

Effect of β-AR stimulation during inhibition of mitochondrial function. Examples of effects on Ca2+ alternans of inhibition of various mitochondrial functions and processes followed by the activation of β-AR signaling pathways are shown. A: inhibition of mitochondrial F1/F0-ATP synthase with oligomycin (Oligo; 1 μg/ml) followed by β1-AR stimulation. B: dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential with the protonophore FCCP (0.1 μM) followed by β2/Gs stimulation. C: inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake via the Ca2+ uniporter with ruthenium red (RuR; 10 μM) followed by nonselective β2-AR stimulation. D: inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ extrusion via the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger with CGP-37157 (CGP; 2.5 μM) followed by β2/Gs stimulation. E: summary data of average alternans ratios in the presence of mitochondrial inhibitors followed by β-AR stimulation. Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of individual atrial myocytes tested.

Depletion of cellular ATP sources diminishes the ability of β-AR stimulation to protect against alternans.

A common result of inhibition of diverse mitochondrial functions is a decrease in mitochondrial ATP production and exhaustion of cellular energy reserves. The diminished ATP supply potentially affects ATP-dependent Ca2+ transport processes, such as cytosolic Ca2+ removal. Decreased cytosolic Ca2+ sequestration has been identified as a key factor causing cardiac alternans. We have previously shown that selective inhibition of glycolytic ATP production (5, 23, 28, 29) or ATP synthesis by mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (16) (Fig. 6) enhanced alternans. In the following set of experiments, we addressed the question of whether β-AR stimulation is capable of decreasing Ca2+ alternans during selective inhibition of glycolytic or mitochondrial ATP production or when both sources of ATP are eliminated.

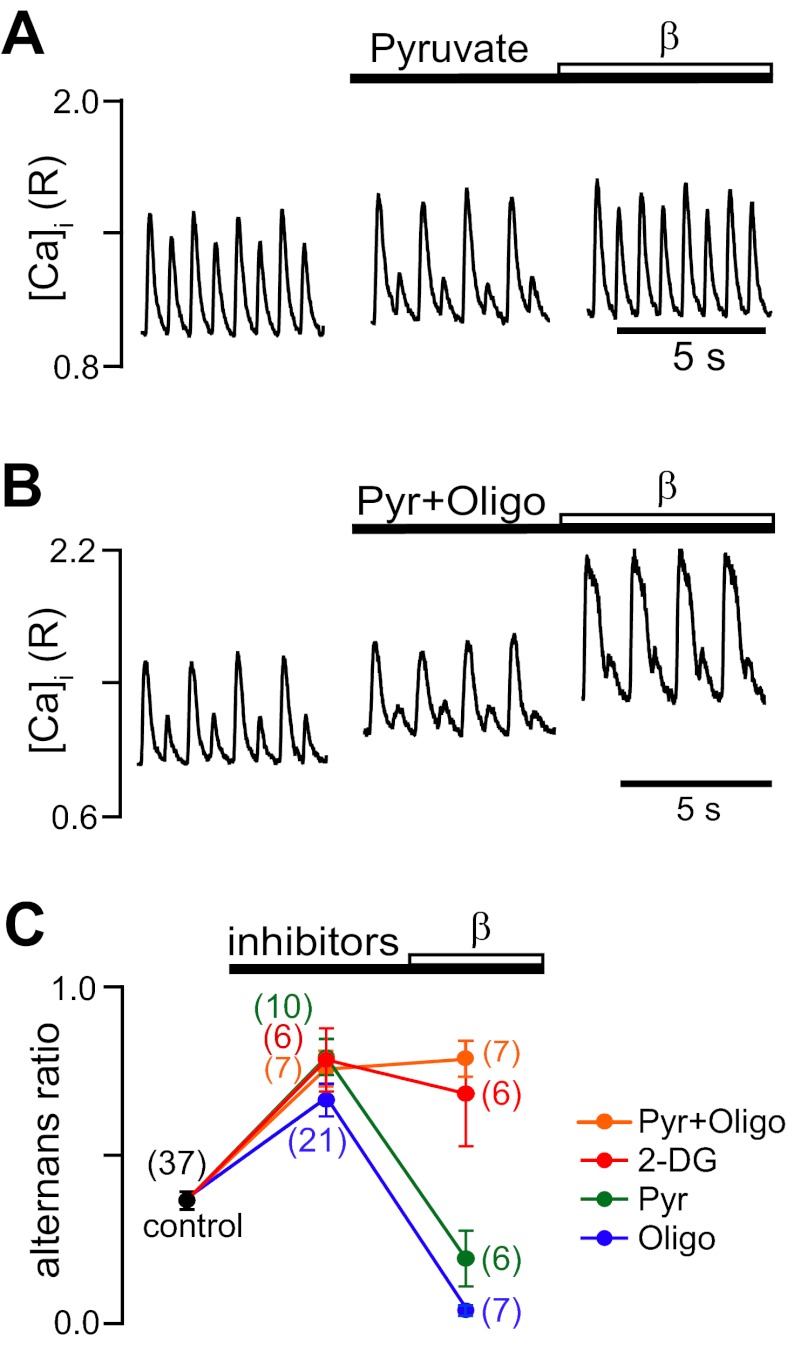

In this set of experiments, mitochondrial ATP production was blocked selectively by oligomycin (inhibition of mitochondrial F1/F0-ATP synthase). Glycolysis was selectively inhibited by pyruvate, as previously described (23, 28, 29). Pyruvate is effectively metabolized by mitochondria, which leads to an increase in citrate and ATP levels (38), which, in turn, inhibits the fructokinase reaction and reduces flux through glycolysis. Inhibition of both ATP sources was achieved by either combined exposure to oligomycin + pyruvate or exposure to 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG). 2-DG is phosphorylated by hexokinase to 2-DG-6-phosphate, which cannot be further metabolized by glycolytic enzymes. Furthermore, 2-DG acts as a sink for ATP because the hexokinase reaction consumes ATP. In the absence of any other metabolic fuel (as under our experimental conditions), 2-DG effectively blocks glycolytic and mitochondrial ATP production because inhibition of glycolysis eliminates the production of substrates for mitochondrial ATP generation. In the presence of oligomycin, 2-DG, pyruvate (Fig. 7A), and oligomycin + pyruvate (Fig. 7B), Ca2+ alternans was enhanced, raising average alternans ratios to 0.70–0.80 (Fig. 7C). β-AR stimulation (β1 and β2) was effective in completely abolishing Ca2+ alternans during inhibition of mitochondrial ATP production with oligomycin. Similarly, β-AR stimulation was effective in abolishing Ca2+ alternans that were previously enhanced by inhibition of glycolytic ATP formation. In contrast, when both sources of ATP were abolished, β-AR stimulation failed to decrease alternans (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, diastolic [Ca2+]i substantially increased and Ca2+ transients were prolonged, consistent with compromised cytosolic Ca2+ removal. As shown in Fig. 7C, separate or combined inhibition of glycolytic and/or mitochondrial ATP production consistently enhanced Ca2+ alternans. When only one of the two cellular ATP sources was inhibited, β-AR stimulation could overcome the inhibitory effect and was able to decrease alternans. However, when both ATP sources were abolished, β-AR stimulation failed to protect against alternans.

Fig. 7.

Effects of β-AR stimulation on Ca2+ alternans during inhibition of glycolytic and mitochondrial ATP production. A: effects of inhibition of glycolysis with pyruvate (Pyr; 10 mM) followed by nonselective β-AR stimulation with ISO (0.1 μM) on pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans. B: effects of combined inhibition of glycolytic (Pyr) and mitochondrial (Oligo; 1 μg/ml) ATP production followed by nonselective β-AR stimulation with ISO. C: summary data of average alternans ratios during glycolytic and/or mitochondrial inhibition followed by β-AR stimulation. β-AR stimulation could overcome the effect of separate inhibition of glycolytic or mitochondrial ATP generation; however, during inhibition of both ATP sources, β-AR stimulation failed to decrease Ca2+ alternans. Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of individual atrial myocytes tested. 2-DG, 2-deoxyglucose.

In conclusion, our results indicate that β-AR stimulation protects against proarrhythmic Ca2+ alternans and involves parallel and complementary pathways regulated by both β1- and β2-AR subtypes. β-AR stimulation-dependent decrease of alternans involves both PKA and CaMKII and depends on a sufficient ATP supply.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the interplay between β-AR signaling, mitochondrial function, and the occurrence of Ca2+ alternans in atrial tissue. The key findings of our investigation were as follows.

First, pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans could be decreased by several distinct pathways linked via G proteins to β1- and β2-AR subtypes. The effect of β-AR stimulation involved activation of the kinases PKA and CaMKII. β1-AR stimulation was linked via Gs to PKA and CaMKII activation. β2-AR stimulation only activated PKA via Gs, similarly to β1-AR stimulation; however, the previously identified β2/Gi/eNOS/NO signaling patway in atrial myocytes had no effect on alternans. Furthermore, basal PKA and CaMKII activity exerted partial protection against alternans.

Second, pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans was enhanced by disruption of mitochondrial function; however, β-AR stimulation could still decrease Ca2+ alternans in the presence of compromised mitochondria, except when mitochondrial impairment included MPTP opening.

Finally, the abolishing effect of β-AR stimulation on Ca2+ alternans depended on sufficient cellular ATP reserves and energy supplies. Selective inhibition of glycolysis or mitochondrial ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation enhanced Ca2+ alternans; however, alternans could still be decreased by β-AR stimulation, suggesting that one ATP source could compensate for the other. Severe depletion of cellular ATP reserves by combined inhibition of glycolytic and mitochondrial ATP production prevented β-AR stimulation from abrogating Ca2+ alternans, suggesting that the protective effect of β-AR signaling ultimately depends on a sufficient ATP supply.

The three β-AR signaling cascades investigated here have been previously established in atrial myocytes (10, 51). In these studies, the importance of these signaling pathways for E-C coupling was demonstrated for the regulation of ion currents (L-type Ca2+ current and ATP-dependent K+ current). The present study extended these earlier observations by investigating how these pathways regulate or modulate Ca2+ alternans in atrial myocytes.

An important finding of our study was that the abolishment of Ca2+ alternans by β-AR stimulation involved the activation of cellular kinases. Whereas β1-AR effects depended on both PKA and CaMK activity, β2-AR-mediated effects appeared to involve solely PKA. Both kinases have well-established phosphorylation targets, including Ca2+-handling proteins that play a key role in E-C coupling and mediate the inotropic effects of β-AR stimulation. Among these proteins, the activity of LTCCs, RyRs, and SERCA are all enhanced by β-AR stimulation-dependent phosphorylation. While β-AR stimulation enhances LTCC currents, Ca2+ entry, and SR Ca2+ load and release, it does not seem to have a direct effect on LTCC as far as alternans are concerned, because the L-type Ca2+ current typically does not alternate during alternans in atrial myocytes (23, 45; but see Refs. 17 and 32). Thus, the abolishing effect appears to be downstream of LTCC augmentation. A prime candidate for a downstream target is beat-to-beat Ca2+ sequestration. It has been convincingly shown that cellular processes, transport pathways, and organelles that clear cytosolic Ca2+ protect against alternans and that conditions that impair cytosolic Ca2+ sequestration promote alternans (for reviews and references, see Refs. 54 and 56). β-AR stimulation strongly enhances SERCA activity, which is accomplished via phosphorylation of the SERCA inhibitory protein phospholamban (30, 33). Phospholamban phosphorylation, principally by PKA (although there is evidence for a role of CaMKII), reduces its inhibitory interactions with SERCA and leads to a dramatic increase in SERCA activity.

Along the same line of arguments, intact mitochondrial function plays an important role in the protection against proarrhythmic alternans. Mitochondria participate in Ca2+ signaling during E-C coupling in two main ways: as a potential Ca2+ sink that can take up and store significant amounts of Ca2+ and as the quantitatively most important source of ATP production that fuels phosphorylation processes or serves as a regulatory cofactor of ion channels and transporters. While it is still a matter of debate (for a discussion of this controversy, see Refs. 9 and 40) as to whether mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and extrusion make a significant contribution to the beat-to-beat regulation of [Ca2+]i (and therefore may also make a direct contribution to Ca2+ alternans), there is no doubt that impairment of mitochondrial function at various levels generates conditions that favor alternans. Dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential and inhibition of mitochondrial function at the level of the electron transport chain, F1/F0-ATP synthase, or Ca2+ uptake and extrusion all enhance Ca2+ alternans (for a review, see Ref. 16; see also Figs. 6 and 7 in the present study). In addition, altering mitochondrial function changes the cellular redox environment (8), and redox modification of the RyR can cause alternans (3). These results, together with the observation that inhibition of glycolysis also induced electromechanical and Ca2+ alternans (see Refs. 23, 28, and 29; see also Figs. 6 and 7 in the present study), suggest that a sufficient ATP supply is crucial for the prevention of alternans and emphasizes a key role of kinases and phosphorylation processes in this context. Our results indicate that selective elimination of one of the two ATP sources per se enhanced Ca2+ alternans but was not sufficient to prevent the protective effect of β-AR signaling against Ca2+ alternans. This observation suggests that if at least one ATP source is functional, the amounts of ATP produced are sufficient to sustain the β-AR effects on Ca2+ signaling. Even though the bulk cellular ATP pool is depleted dramatically during inhibition of mitochondrial ATP production (since mitochondria generate up to 90% of cellular ATP in cardiac myocytes, which is primarily consumed to sustain contractile activity), glycolysis-derived ATP appears to suffice to support β-AR effects on Ca2+ alternans. This may in part be explained by the observation that ATP derived from glycolysis is used preferentially by membrane ion transport mechanisms. The close physical association of glycolytic enzymes with ATP-dependent ion transporters and channels form functional microcompartments where source and utilization sites for ATP are intimately linked. Such arrangements have been demonstrated for Na+-K+-ATPase (18), ATP-dependent K+ channels (55), and the SERCA pump (62) and have been proposed for the RyR Ca2+-release channel as a potential contributing factor to alternans (5, 23, 28, 29).

Modulation of RyR function through β-AR stimulation represents an additional mechanism through which β-AR stimulation protects against alternans. RyRs are subject to phosphorylation by PKA and CaMKII (2, 19, 22, 34, 35). The signaling events that occur downstream of β-AR stimulation and their effects on RyR activity remain highly contentious (for reviews, see Refs. 21 and 63), and the ramifications of RyR phosphorylation for cardiac function in health and disease have remained a highly debated and controversial issue (for a recent update on the debate, see Ref. 4). Nonetheless, we (45) have previously shown that in atrial myocytes, refractoriness of SR Ca2+ release via RyRs and beat-to-beat alternations in the kinetics of RyR and SR Ca2+-release restitution constitute a key defining factor of cardiac alternans. Factors that sensitize the RyR to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release can accelerate restitution and therefore can overcome Ca2+ alternans. This can be demonstrated with the RyR-sensitizing agent caffeine at low concentrations, and the effects were strikingly similar to the effects of ISO stimulation (45). Thus, enhanced Ca2+ sequestration together with β-AR-mediated effects on the RyR appear to act in tandem to protect against pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans.

The abolishment of pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans by β-AR stimulation is controversial and not unique to atrial tissue. As discussed in the Introduction, β-AR stimulation has also been shown to facilitate alternans. At the cellular level, it is believed that this can occur when a strong effect of β-AR stimulation on SR Ca2+ load and fractional SR Ca2+ release outweighs the protective effect of cytosolic Ca2+ sequestration (54). Furthermore, we (23) have previously shown that in feline ventricular myocytes, ISO stimulation reversibly abolished electrical (action potential duration) and mechanical (cell shortening) alternans, where the alternations in action potential duration subsided in concert with the changes in contration, indicating that electrical and mechanical (or Ca2+) activity are tightly coupled during alternans.

In summary, we demonstrated here that β-AR stimulation abolishes pacing-induced Ca2+ alternans even under conditions where inhibition of mitochondrial function facilitates Ca2+ alternans. The protective effect of β-AR stimulation is mediated by parallel and complementary signaling cascades. The redundancy in the β-AR signaling-mediated protection against proarrhythmic alternans represents an inherent safety mechanism to prevent arrhythmogenic Ca2+ release in the heart during enhanced sympathetic tone.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-62231, HL-80101, and HL-101235 and the Leducq Foundation (to L. A. Blatter) as well as the American Heart Association-Midwest Affiliate (to S. M. Florea).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.M.F. and L.A.B. conception and design of research; S.M.F. performed experiments; S.M.F. and L.A.B. analyzed data; S.M.F. and L.A.B. interpreted results of experiments; S.M.F. and L.A.B. prepared figures; S.M.F. and L.A.B. drafted manuscript; S.M.F. and L.A.B. edited and revised manuscript; S.M.F. and L.A.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adam L, Bouvier M, Jones TL. Nitric oxide modulates β2-adrenergic receptor palmitoylation and signaling. J Biol Chem 274: 26337–26343, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ai X, Curran JW, Shannon TR, Bers DM, Pogwizd SM. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ Res 97: 1314–1322, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Belevych AE, Terentyev D, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Terentyeva R, Sridhar A, Nishijima Y, Wilson LD, Cardounel AJ, Laurita KR, Carnes CA, Billman GE, Gyorke S. Redox modification of ryanodine receptors underlies calcium alternans in a canine model of sudden cardiac death. Cardiovasc Res 84: 387–395, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bers DM. Ryanodine receptor S2808 phosphorylation in heart failure: smoking gun or red herring. Circ Res 110: 796–799, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blatter LA, Kockskamper J, Sheehan KA, Zima AV, Huser J, Lipsius SL. Local calcium gradients during excitation-contraction coupling and alternans in atrial myocytes. J Physiol 546: 19–31, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clusin WT. Mechanisms of calcium transient and action potential alternans in cardiac cells and tissues. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1–H10, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Diego C, Chen F, Xie LH, Dave AS, Thu M, Rongey C, Weiss JN, Valderrabano M. Cardiac alternans in embryonic mouse ventricles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H433–H440, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dedkova EN, Blatter LA. Characteristics and function of cardiac mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. J Physiol 587: 851–872, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dedkova EN, Blatter LA. Mitochondrial Ca2+ and the heart. Cell Calcium 44: 77–91, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dedkova EN, Wang YG, Blatter LA, Lipsius SL. Nitric oxide signalling by selective β2-adrenoceptor stimulation prevents ACh-induced inhibition of β2-stimulated Ca2+ current in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol 542: 711–723, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dumitrescu C, Narayan P, Efimov IR, Cheng Y, Radin MJ, McCune SA, Altschuld RA. Mechanical alternans and restitution in failing SHHF rat left ventricles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1320–H1326, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eisner DA, Choi HS, Diaz ME, O'Neill SC, Trafford AW. Integrative analysis of calcium cycling in cardiac muscle. Circ Res 87: 1087–1094, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eisner DA, Li Y, O'Neill SC. Alternans of intracellular calcium: mechanism and significance. Heart Rhythm 3: 743–745, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Euler DE. Cardiac alternans: mechanisms and pathophysiological significance. Cardiovasc Res 42: 583–590, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Euler DE, Guo H, Olshansky B. Sympathetic influences on electrical and mechanical alternans in the canine heart. Cardiovasc Res 32: 854–860, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Florea SM, Blatter LA. The role of mitochondria for the regulation of cardiac alternans. Front Physiol 1: 1–9, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fox JJ, McHarg JL, Gilmour RF., Jr Ionic mechanism of electrical alternans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H516–H530, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Glitsch HG, Tappe A. Change of Na+ pump current reversal potential in sheep cardiac Purkinje cells with varying free energy of ATP hydrolysis. J Physiol 484: 605–616, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gonano LA, Sepulveda M, Rico Y, Kaetzel M, Valverde CA, Dedman J, Mattiazzi A, Vila Petroff M. Calcium-calmodulin kinase II mediates digitalis-induced arrhythmias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 4: 947–957, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hiromoto K, Shimizu H, Furukawa Y, Kanemori T, Mine T, Masuyama T, Ohyanagi M. Discordant repolarization alternans-induced atrial fibrillation is suppressed by verapamil. Circ J 69: 1368–1373, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Houser SR. Does protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor play any role in adrenergic regulation of calcium handling in health and disease? Circ Res 106: 1672–1674, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huke S, Bers DM. Ryanodine receptor phosphorylation at serine 2030, 2808 and 2814 in rat cardiomyocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 376: 80–85, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huser J, Wang YG, Sheehan KA, Cifuentes F, Lipsius SL, Blatter LA. Functional coupling between glycolysis and excitation-contraction coupling underlies alternans in cat heart cells. J Physiol 524: 795–806, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kameyama M, Hirayama Y, Saitoh H, Maruyama M, Atarashi H, Takano T. Possible contribution of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump function to electrical and mechanical alternans. J Electrocardiol 36: 125–135, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kilts JD, Gerhardt MA, Richardson MD, Sreeram G, Mackensen GB, Grocott HP, White WD, Davis RD, Newman MF, Reves JG, Schwinn DA, Kwatra MM. β(2)-Adrenergic and several other G protein-coupled receptors in human atrial membranes activate both Gs and Gi. Circ Res 87: 705–709, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klingenheben T, Gronefeld G, Li YG, Hohnloser SH. Effect of metoprolol and d,l-sotalol on microvolt-level T-wave alternans. Results of a prospective, double-blind, randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol 38: 2013–2019, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kobayashi S, Susa T, Tanaka T, Murakami W, Fukuta S, Okuda S, Doi M, Wada Y, Nao T, Yamada J, Okamura T, Yano M, Matsuzaki M. Low-dose β-blocker in combination with milrinone safely improves cardiac function and eliminates pulsus alternans in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Circ J 76: 1646–1653, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kockskamper J, Blatter LA. Subcellular Ca2+ alternans represents a novel mechanism for the generation of arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol 545: 65–79, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kockskamper J, Zima AV, Blatter LA. Modulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release by glycolysis in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol 564: 697–714, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kranias EG, Solaro RJ. Phosphorylation of troponin I and phospholamban during catecholamine stimulation of rabbit heart. Nature 298: 182–184, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Laurita KR, Rosenbaum DS. Cellular mechanisms of arrhythmogenic cardiac alternans. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 97: 332–347, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li Y, Diaz ME, Eisner DA, O'Neill S. The effects of membrane potential, SR Ca2+ content and RyR responsiveness on systolic Ca2+ alternans in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 587: 1283–1292, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lindemann JP, Jones LR, Hathaway DR, Henry BG, Watanabe AM. β-Adrenergic stimulation of phospholamban phosphorylation and Ca2+-ATPase activity in guinea pig ventricles. J Biol Chem 258: 464–471, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell 101: 365–376, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Morimoto S, O-Uichi J, Kawai M, Hoshina T, Kusakari Y, Komukai K, Sasaki H, Hongo K, Kurihara S. Protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of ryanodine receptors increases Ca2+ leak in mouse heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 390: 87–92, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Myles RC, Burton FL, Cobbe SM, Smith GL. The link between repolarisation alternans and ventricular arrhythmia: does the cellular phenomenon extend to the clinical problem? J Mol Cell Cardiol 45: 1–10, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Narayan SM, Bode F, Karasik PL, Franz MR. Alternans of atrial action potentials during atrial flutter as a precursor to atrial fibrillation. Circulation 106: 1968–1973, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Newsholme EA, Randle PJ, Manchester KL. Inhibition of the phosphofructokinase reaction in perfused rat heart by respiration of ketone bodies, fatty acids and pyruvate. Nature 193: 270–271, 1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ng GA, Brack KE, Patel VH, Coote JH. Autonomic modulation of electrical restitution, alternans and ventricular fibrillation initiation in the isolated heart. Cardiovasc Res 73: 750–760, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. O'Rourke B, Blatter LA. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake: tortoise or hare? J Mol Cell Cardiol 46: 767–774, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pabbidi MR, Ji X, Samarel AM, Lipsius SL. Laminin enhances β2-adrenergic receptor stimulation of L-type Ca2+ current via cytosolic phospholipase A2 signalling in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol 587: 4785–4797, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ponicke K, Groner F, Heinroth-Hoffmann I, Brodde OE. Agonist-specific activation of the β2-adrenoceptor/Gs-protein and β2-adrenoceptor/Gi-protein pathway in adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes. Br J Pharmacol 147: 714–719, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rosenbaum DS. T wave alternans: a mechanism of arrhythmogenesis comes of age after 100 years. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 12: 207–209, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rosenbaum DS, Jackson LE, Smith JM, Garan H, Ruskin JN, Cohen RJ. Electrical alternans and vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias. N Engl J Med 330: 235–241, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shkryl VM, Maxwell JT, Domeier TL, Blatter LA. Refractoriness of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca release determines Ca alternans in atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H2310–H2320, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Steinberg SF. The molecular basis for distinct beta-adrenergic receptor subtype actions in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res 85: 1101–1111, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ter Keurs HE, Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev 87: 457–506, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Walker ML, Rosenbaum DS. Cellular alternans as mechanism of cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Heart Rhythm 2: 1383–1386, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Walker ML, Rosenbaum DS. Repolarization alternans: implications for the mechanism and prevention of sudden cardiac death. Cardiovasc Res 57: 599–614, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang W, Zhu W, Wang S, Yang D, Crow MT, Xiao RP, Cheng H. Sustained β1-adrenergic stimulation modulates cardiac contractility by Ca2+/calmodulin kinase signaling pathway. Circ Res 95: 798–806, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang YG, Dedkova EN, Steinberg SF, Blatter LA, Lipsius SL. β2-Adrenergic receptor signaling acts via NO release to mediate ACh-induced activation of ATP-sensitive K+ current in cat atrial myocytes. J Gen Physiol 119: 69–82, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang YG, Rechenmacher CE, Lipsius SL. Nitric oxide signaling mediates stimulation of L-type Ca2+ current elicited by withdrawal of acetylcholine in cat atrial myocytes. J Gen Physiol 111: 113–125, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang YG, Samarel AM, Lipsius SL. Laminin binding to β1-integrins selectively alters β1- and β2-adrenoceptor signalling in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol 527: 3–9, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weiss JN, Karma A, Shiferaw Y, Chen PS, Garfinkel A, Qu Z. From pulsus to pulseless: the saga of cardiac alternans. Circ Res 98: 1244–1253, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Weiss JN, Lamp ST. Cardiac ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Evidence for preferential regulation by glycolysis. J Gen Physiol 94: 911–935, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weiss JN, Nivala M, Garfinkel A, Qu Z. Alternans and arrhythmias: from cell to heart. Circ Res 108: 98–112, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wohlfart B. Analysis of mechanical alternans in rabbit papillary muscle. Acta Physiol Scand 115: 405–414, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wu JY, Vereecke J, Carmeliet E, Lipsius SL. Ionic currents activated during hyperpolarization of single right atrial myocytes from cat heart. Circ Res 68: 1059–1069, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wu Y, Clusin WT. Calcium transient alternans in blood-perfused ischemic hearts: observations with fluorescent indicator fura red. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 273: H2161–H2169, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Xiao RP, Avdonin P, Zhou YY, Cheng H, Akhter SA, Eschenhagen T, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ, Lakatta EG. Coupling of β2-adrenoceptor to Gi proteins and its physiological relevance in murine cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 84: 43–52, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Xiao RP, Ji X, Lakatta EG. Functional coupling of the β2-adrenoceptor to a pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein in cardiac myocytes. Mol Pharmacol 47: 322–329, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Xu KY, Zweier JL, Becker LC. Functional coupling between glycolysis and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport. Circ Res 77: 88–97, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yamaguchi N, Meissner G. Does Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase deltac activate or inhibit the cardiac ryanodine receptor ion channel? Circ Res 100: 293–295, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]