Abstract

Ciliopathies are a heterogeneous group of diseases that exhibit broad clinical phenotypes, including renal cysts, retinal degeneration, and cerebellar vermis aplasia. Nephronophthisis (NPHP) is a renal ciliopathy that causes chronic kidney disease and is characterized by kidney cysts at the cortico-medullary border. Among the 10 different disease-causing genes (NPHP1-NPHP10), mutations in NPHP3, NPHP6, or NPHP8 cause the most severe ciliopathy variants of NPHP, Joubert syndrome, and Meckel Syndrome. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that loss of function of these three most severe disease-associated genes leads to morphological defects in a three-dimensional (3D) renal cell culture [murine (m) inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) 3] model by either lack of cilia formation and/or cell polarity defects. Stable knockdown cell lines were examined in 3D spheroid culture followed by rhodamine-phalloidin staining to assess spheroid architecture. We observed significantly higher percentages of abnormal spheroids for all three stable cell lines compared with control short-hairpin RNA cells. In addition, stable knockdown of Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8 results in reduced cilia numbers and elevated cAMP levels in mIMCD3 cells. We demonstrate that, following gene knockdown of Nphp3, Nphp6, or Nphp8, treatment with the somatostatin agonist octreotide (2 μM) reduces the percentage of abnormal spheroids compared with control. This study reveals that the loss of Nphp3, Nphp6, or Nphp8 leads to cilia abnormalities and cell polarity defects, resulting in spheroid abnormalities, which can be rescued by inhibiting cAMP levels with octreotide treatment.

Keywords: nephronophthisis, three-dimensional, polycystic kidney disease, spheroids

nephronophthisis-related ciliopathies (NPHP-RC) are a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of diseases that exhibit shared clinical phenotypes, including renal cysts, retinal degeneration, and cerebellar vermis aplasia (6). Among the 10 different NPHP disease-causing genes (NPHP1-NPHP10), mutations in NPHP3, NPHP6, or NPHP8 cause the most severe NPHP-RC, Joubert Syndrome, and Meckel Syndrome (7). Studies into these diseases have revealed that virtually all of the gene products involved in the pathogenesis in humans, mice, or zebrafish are expressed at the primary cilia-centrosome complex (6, 15). Cilia are a key component of a number of signal transduction pathways, including Hedgehog (shh) (2) and Wnt signaling (3, 5). Centrosomal proteins regulate cell polarity and oriented cell division and participate in the mitotic spindle formation during mitosis (3, 13).

Seventeen ciliopathy genes are known to cause NPHP-RC if mutated (for review, see Ref. 6), whereas NPHP3, NPHP6/Cep290, or NPHP8/RPGRIP1L mutations lead to the most severe ciliopathy phenotypes, including NPHP-Joubert syndrome and Meckel syndrome. Because mutation of these genes causes overlapping disease, phenotypes suggest that the mutated disease proteins may interact and function in a common pathway (13). Although the pathogenesis has been studied extensively, no clear pathways have been delineated, and no effective treatment has been developed.

Recent studies have established that cAMP stimulates mural epithelial cell proliferation and secretion of fluid into cysts in patients with polycystic kidney disease (PKD) (16). Elevated cAMP levels are found in the kidney, liver, vascular smooth muscle, and choroid plexus, in various animal models of PKD and NPHP (4, 9, 14, 16). A recent study from our group has demonstrated that Nphp10 (Sdccag8) disappears from cell junctions upon treatment of cells with the cAMP analog 8-bromo-cAMP (11). These studies prompted us to examine whether loss of function of NPHP-RC genes causes cellular abnormalities in the renal cystic disease model of three-dimensional (3D) spheroids (10) and whether the effect can be rescued by modulation of cAMP levels.

METHODS

Generation of stable knockdown murine inner medullary collecting duct cells: shRNA duplexes were designed and cloned into RNAi-Ready pSIREN-RetroQ vector (Clonetech). Short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) target sequences for Nphp genes were as follows: Nphp3 (5′-GGATTAATCTACCACCGTTTG-3′, 5′-GGATTCCACTCCAGAAGAAGA-3′, and 5′-GGACATACACGATGAGCAAGA-3′), Nphp6 (5′-GGAAGAAATTGTTCAGCAAAG-3′, 5′-GGAAGACCTTCATGTTCTTCA-3′, and 5′-GGAGCAGACAGTAGCAGAACA-3′), and Nphp8 (5′-GGATCAAGCTATTCGACTTTA-3′, 5′-GGATTTGGATCGCTACCTTAA-3′, and 5′-GGGAAATGCAACAAGGGAAAG-3′).

Retrovirus was generated by transfecting 293T cells with the shRNA constructs along with pVSV and p-gag-pol constructs. Murine (m) inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) 3 cells were infected with the supernatant. IMCD3 cells were then selected with puromycin resistance for 10 days at 10 μg/ml.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagene). First-strand cDNA was performed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Accumulation of PCR products was measured in real time by using iTaq SYBR green supermix with the MyiQ Single Color Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad).

Spheroid assay.

3D spheroid cell culture was performed using Geltrex Reduced Growth Factor Basement Membrane Matrix (Invitrogen) in chamber slides. Spheroids were stained with rhodamine-phalloidin and DAPI. The spheroid architecture was examined under an inverted confocal microscope (Leica).

Immunofluorescence studies.

mIMCD3 cell lines were grown on the filter and serum starved for 48 h. Cells were fixed and stained with acetylated α-tubulin for the cilia and anti-somatostatin receptor antibodies. Anti-mouse Alexa fluor 594 and anti-rabbit Alexa fluor-488 were used as secondary antibodies and DAPI as nuclear stain. The membrane filters were mounted on slides, and the images were taken under an inverted confocal microscope (Leica). A total of 100 cells were counted for each group for cilia quantification.

Measurement of intracellular cAMP.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed on cell lysates in triplicate samples using a Direct Cyclic AMP Enzyme Immunoassay kit (Arbor Assays).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

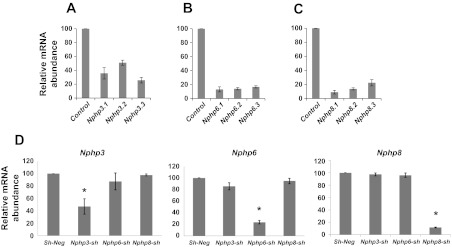

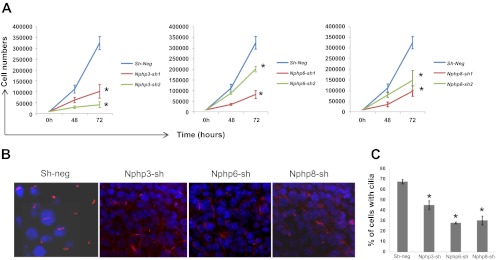

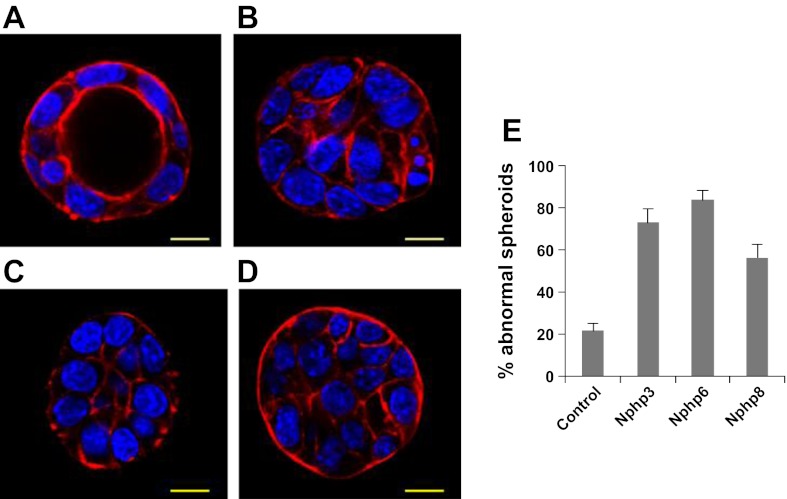

In the present study, we generated mIMCD3 cell lines of stable knockdown of Nphp3, Nphp6, or Nphp8 with retroviral delivery of three shRNA duplexes for each gene. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed that all three shRNA duplexes for each gene reduced mRNA expression of each gene. However, Nphp3.1, Nphp6.1, and Nphp8.1 were more efficient than the other two shRNA duplexes for the same gene (Fig. 1, A–C). To test whether knockdown of Nphp subtype affects other Nphp mRNA expression, we used the cDNAs from these cells and tested in the context of Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8 primer sets in a reciprocal real-time PCR analysis. These results confirm the specificity of the knockdown by shRNA duplexes (Fig. 1D). To test the effects of Nphp knockdown on the cell proliferation, growth assay was performed by plating an equal number of cells and counting them by an automatic counter (TC10; Bio-Rad) at different time intervals. Our data suggested retarded growth of Nphp knockdown cells compared with the sh-neg control cell line (Fig. 2A). To investigate the roles of Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8 gene products in tissue architecture, we examined Nphp knockdown cell lines in a 3D spheroid culture system that reflects the cell biology of kidney collecting duct. Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8 knockdown mIMCD3 cell lines were grown in the 3D culture system for 3–4 days to develop spheroid structure. Spheroids were then stained with rhodamine-phalloidin for F-actin and DAPI (for nuclear staining) to visualize spheroid architecture under an inverted confocal microscopy. Spheroid architecture was examined by focusing at the equator of the spheroids to visualize lumen formation. Spheroids with no lumen and/or misaligned nuclei were considered as abnormal (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 1.

mRNA levels in murine (m) inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) 3 cell lines with stable knockdown of nephronophthisis Nphp3, Nphp6, or Nphp8 by real-time q-PCR analysis. Stable knockdown of Nphp3 (A), Nphp6 (B), and Nphp8 (C) was performed by retrovirus-mediated short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression in mIMCD3 cells. Three different duplexes for Nphp3 (Nphp3.1, Nphp3.2, and Nphp3.3), Nphp6 (Nphp6.1, Nphp6.2, and Nphp6.3), and Nphp8 (Nphp8.1, Nphp8.2, and Nphp8.3) were used to stably knock down the genes. Relative mRNA levels were evaluated by real-time PCR analysis. Triplicate sample for each mRNA was used to evaluate the level of mRNA expression. Data represented in the diagram are %means ± SD for each mRNA sample after normalization with GAPDH mRNA abundance. shRNA sequences used for stable knockdowns are available from the authors. D: knockdown of specific Nphp gene in IMCD3 cells does not affect other Nphp subtypes. Real-time PCR analysis using cDNA from mIMCD3 cells with stable knockdown with Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8 and specific primers for corresponding genes (Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8) revealed that lower mRNA level was detected only in the Nphp3 knockdown cells but not in the Nphp6 or Nphp8 cell lines. Similarly, knock down of Nphp6 was detected only in the Nphp6 cell lines but not in either Nphp3 or Nphp8 cell lines. Analysis of Nphp8 mRNA revealed the specific knockdown of Nphp8 cell line but not in the Nphp3 or Nphp6 cell lines. mRNA from unrelated shRNA-derived cells (sh-neg) were considered to be 100% for all three knockdown analyses. Relative mRNA expression data from triplicate samples were determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method and represented as means ± SD. *Significance level at P < 0.001.

Fig. 2.

Stable knockdown of Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8 results in retarded cell proliferation and reduced cilia numbers. A: knockdown of Nphp genes in mIMCD3 results in retarded cell proliferation. Cell proliferation for sh-neg and Nphp3-sh, Nphp6-sh, and Nphp8-sh was evaluated based on the cell number at 48 and 72 h after 10 × 103 cells were plated. Line diagram represents the cell growth curve when cell counts were plotted against time points for the indicated cell lines. Statistical significance was determined by t-test using means and SDs of the respective groups. *Level of significance (P < 0.001). B: representative confocal images of cilia (in red) in sh-neg control, Nphp3-sh, Nphp6-sh, and Nphp8-sh mIMCD3 cell lines. C: quantitative representation of cilia numbers. Cilia were counted from the confocal images taken from three different experiments and plotted as percentages of nucleus (DAPI stained, in blue). *P < 0.001, significance level from a 2-tailed t-test.

Fig. 3.

Nphp knockdown disrupts spheroid growth in mIMCD3 cells. Three-dimensional (3D) spheroids derived from Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8 stable knockdown mIMCD3 cells were stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin for F-actin and DAPI for nuclear stain. Spheroid morphology from control (A), Nphp3 (B), Nphp6 (C), or Nphp8 (D) cell lines were judged by focusing to the equator plane of each spheroid using the z-axis of a confocal microscope (Leica). A total of 150 spheroids for each group from three different experiments were evaluated. The percentages of abnormal spheroids for different knockdown genes are plotted in a bar diagram (E). Scale bars = 10 μm (B). Error bars represents the SD from the mean values.

We found significantly higher percentages of abnormal spheroids for all three stable knockdown cell lines (Nphp3, 73%; Nphp6, 84%; and Nphp8, 56%) compared with control shRNA cells (21%) (Fig. 3B). Spheroid abnormalities from cells with knockdown of Nphp genes by small-interfering RNA have also been reported in a recent study (13).

We investigated the cilia defects by growing sh-neg, Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8 cell lines on membrane filters under conditions of ciliogenesis (see methods). Cilia quantification data (Fig. 2, B and C) suggested that lack of all three Nphp genes under this study resulted in significant reduction in cilia numbers in the stable knockdown cells. Because cilia are sensory organelles for the kidney cells, lack of cilia might perturb signaling events critical for normal polarity maintenance.

Previous studies have established that cAMP plays a central role in the progression of cystic disease in patients with autosomal dominant PKD by stimulating epithelial cell proliferation and secretion of fluid into cysts (12). This has provided a strong rationale for therapies targeting cAMP signaling. Somatostatin analogs acting on Gi protein-coupled receptors provided an alternative path to inhibit cAMP signaling in tubular epithelial cells in patients with PKD. Research studies showed that somatostatin receptor inhibitor octreotide significantly reduces cAMP levels and rates of cysts expansion in freshly isolated bile ducts from PCK rats grown in 3D culture (9).

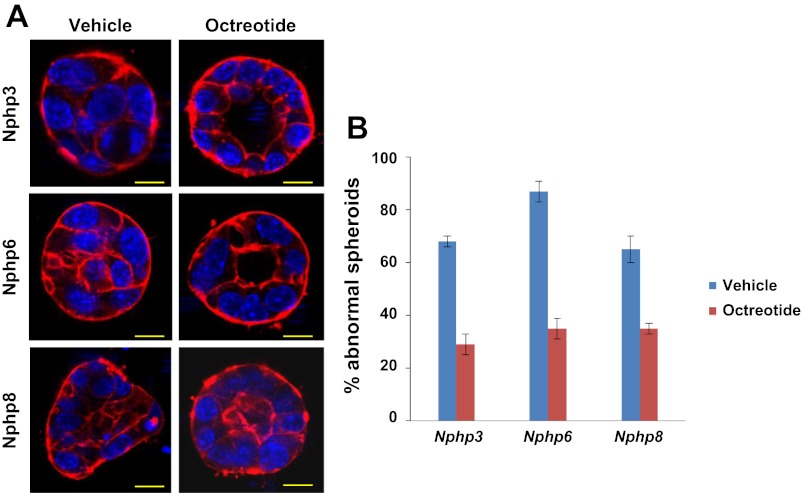

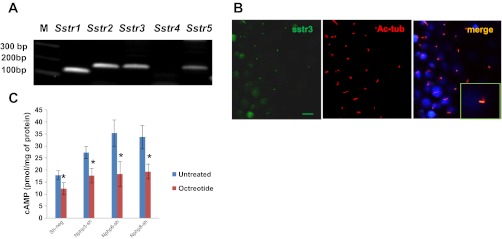

We treated Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8 knockdown spheroids with the somatostatin agonist octreotide (2 μM) and observed that treatment of knockdown spheroids with octreotide (2 μM) reduced the percentage of abnormal spheroids to 29% (Nphp3), 35% (Nphp6), and 35% (Nphp8), whereas vehicle control abnormal spheroids were 68% (Nphp3), 87% (Nphp6), and 65% (Nphp8) (Fig. 4). Because octreotide was a known ligand for somatostatin receptors (Sstr), we evaluated the mRNA expression level of somatostatin receptors (Sstr1–5) using cDNA from the mIMCD3 cell line by RT-PCR analysis. Our expression data suggested that, except for Sstr4, all other Sstr mRNAs were abundant in mIMCD3 cells (Fig. 5A). In addition, imaging analysis revealed that only Sstr3 was localized to the primary cilium (Fig. 5B). Our data are in agreement with the studies by others where it has been clearly demonstrated that a consensus sequence of third intracellular loop3 of Sstr3 was critical for cilia localization (1). We then analyzed the intracellular cAMP concentrations in octreotide-treated or untreated control, Nphp3-sh, Nphp6-sh, and Nphp8-sh cell lines. Our data suggested that elevated intracellular cAMP levels in Nphp knockdown cells compared with the control sh-neg cells. Octrotide treatment significantly reduces cAMP levels in the Nphp knockdown cells or control cells (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 4.

Protective effects of octreotide on spheroid abnormalities caused by knockdown of Nphp3, Nphp6, or Nphp8 genes in mIMCD3 cells. IMCD3 cells with stable knockdown of Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8 were treated with either vehicle (DMSO) or 2 μM octreotide during spheroid growth for 96 h. Spheroids were stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin and DAPI. The morphology was examined by a confocal microscope. The percentages of abnormal spheroids were plotted in the bar diagram. Scale bars = 10 μm (B). Representative images for different cell lines are shown in A. A total of 180 (n = 180) spheroids from three different experiments were evaluated. Error bars represent the SD from the mean values.

Fig. 5.

Octreotide treatment inhibits elevated cAMP levels upon Nphp knockdown in IMCD3 cells. A: IMCD3 cells express somatostatin receptors. Designed primers for five somatostatin receptors (Sstr1, Sstr2, Sstr3, Sstr4, and Sstr5) and cDNAs from IMCD3 cells were used to analyze mRNA expression by the RT-PCR method. Agarose gel electrophoresis data revealed that all five somatostatin receptors except Sstr4 were abundant in IMCD3 cells. M, molecular weight marker. B: somatostatin receptor 3 (Sstr3) is localized to the cilia. Ciliated IMCD3 cells were stained with acetylated α-tubulin (Ac-tub) and Sstr3 antibodies. Confocal immunofluorescence images were taken for cilia (red) and Sstr3 (green) localization. Merged image revealed Sstr3 localization at the cilia. Magnified image was shown in the inset. C: bar diagram represents elevated intracellular cAMP levels upon Nphp3, Nphp6, and Nphp8 knockdown compared with the control sh-neg cells. Treatment of octreotide (2 μM) significantly reduced cAMP levels. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed on triplicate samples using the Direct Cyclic AMP Enzyme Immunoassay kit (Arbor Assays). Statistical significance level was determined by t-test using means and SDs of triplicate samples. Two-tailed t-test was performed to test the significance of difference using means and SDs. *Significance level (P < 0.05).

This study reveals that lack of Nphp3, Nphp6, or Nphp8 leads to cell polarity defects, resulting in spheroid abnormalities that can be rescued by inhibiting intracellular cAMP levels with octreotide treatment. Recently, in a randomized clinical trial, long-acting octreotide has been reported to slow down disease progression in patients with polycystic liver disease (8). Our study confirms that manipulation of the cAMP pathways could be one of the therapeutic approaches in treating patients with NPHP-RC.

GRANTS

F. Hildebrandt is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, a Frederick G. L. Huetwell Professor, and a Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Scientist. This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases to F. Hildebrandt (DK-068306 and DK-090917), the March of Dimes (6-F711-241), and the Center for Organogenesis of the University of Michigan.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: A.K.G., T.W.H., and F.H. conception and design of research; A.K.G. performed experiments; A.K.G. analyzed data; A.K.G. interpreted results of experiments; A.K.G. prepared figures; A.K.G. drafted manuscript; T.W.H. and F.H. edited and revised manuscript; F.H. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Berbari NF, Johnson AD, Lewis JS, Askwith CC, Mykytyn K. Identification of ciliary localization sequences within the third intracellular loop of G protein-coupled receptors. Mol Biol Cell 19: 1540–1547, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Corbit KC, Shyer AE, Dowdle WE, Gaulden J, Singla V, Chen MH, Chuang PT, Reiter JF. Kif3a constrains beta-catenin-dependent Wnt signalling through dual ciliary and non-ciliary mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol 10: 70–76, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fischer E, Legue E, Doyen A, Nato F, Nicolas JF, Torres V, Yaniv M, Pontoglio M. Defective planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet 38: 21–23, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gattone VH, 2nd, Wang X, Harris PC, Torres VE. Inhibition of renal cystic disease development and progression by a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist. Nat Med 9: 1323–1326, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gerdes JM, Liu Y, Zaghloul NA, Leitch CC, Lawson SS, Kato M, Beachy PA, Beales PL, DeMartino GN, Fisher S, Badano JL, Katsanis N. Disruption of the basal body compromises proteasomal function and perturbs intracellular Wnt response. Nat Genet 39: 1350–1360, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hildebrandt F, Benzing T, Katsanis N. Ciliopathies. N Engl J Med 364: 1533–1543, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hildebrandt F, Zhou W. Nephronophthisis-associated ciliopathies. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1855–1871, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page LJ, Kubly VJ, Bergstralh EJ, Li X, Kim B, King BF, Glockner J, Holmes DR, 3rd, Rossetti S, Harris PC, LaRusso NF, Torres VE. Randomized clinical trial of long-acting somatostatin for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1052–1061, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Masyuk TV, Masyuk AI, Torres VE, Harris PC, Larusso NF. Octreotide inhibits hepatic cystogenesis in a rodent model of polycystic liver disease by reducing cholangiocyte adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate. Gastroenterology 132: 1104–1116, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O'Brien LE, Jou TS, Pollack AL, Zhang Q, Hansen SH, Yurchenco P, Mostov KE. Rac1 orientates epithelial apical polarity through effects on basolateral laminin assembly. Nat Cell Biol 3: 831–838, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Otto EA, Hurd TW, Airik R, Chaki M, Zhou W, Stoetzel C, Patil SB, Levy S, Ghosh AK, Murga-Zamalloa CA, van Reeuwijk J, Letteboer SJ, Sang L, Giles RH, Liu Q, Coene KL, Estrada-Cuzcano A, Collin RW, McLaughlin HM, Held S, Kasanuki JM, Ramaswami G, Conte J, Lopez I, Washburn J, Macdonald J, Hu J, Yamashita Y, Maher ER, Guay-Woodford LM, Neumann HP, Obermuller N, Koenekoop RK, Bergmann C, Bei X, Lewis RA, Katsanis N, Lopes V, Williams DS, Lyons RH, Dang CV, Brito DA, Dias MB, Zhang X, Cavalcoli JD, Nurnberg G, Nurnberg P, Pierce EA, Jackson PK, Antignac C, Saunier S, Roepman R, Dollfus H, Khanna H, Hildebrandt F. Candidate exome capture identifies mutation of SDCCAG8 as the cause of a retinal-renal ciliopathy. Nat Genet 42: 840–850, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patel V, Chowdhury R, Igarashi P. Advances in the pathogenesis and treatment of polycystic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 99–106, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sang L, Miller JJ, Corbit KC, Giles RH, Brauer MJ, Otto EA, Baye LM, Wen X, Scales SJ, Kwong M, Huntzicker EG, Sfakianos MK, Sandoval W, Bazan JF, Kulkarni P, Garcia-Gonzalo FR, Seol AD, O'Toole JF, Held S, Reutter HM, Lane WS, Rafiq MA, Noor A, Ansar M, Devi AR, Sheffield VC, Slusarski DC, Vincent JB, Doherty DA, Hildebrandt F, Reiter JF, Jackson PK. Mapping the NPHP-JBTS-MKS protein network reveals ciliopathy disease genes and pathways. Cell 145: 513–528, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Torres VE, Wang X, Qian Q, Somlo S, Harris PC, Gattone VH., 2nd Effective treatment of an orthologous model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Med 10: 363–364, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Watnick T, Germino G. From cilia to cyst. Nat Genet 34: 355–356, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamaguchi T, Wallace DP, Magenheimer BS, Hempson SJ, Grantham JJ, Calvet JP. Calcium restriction allows cAMP activation of the B-Raf/ERK pathway, switching cells to a cAMP-dependent growth-stimulated phenotype. J Biol Chem 279: 40419–40430, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]