Abstract

We previously showed that luminal flow stimulates thick ascending limb (TAL) superoxide (O2−) production by stretching epithelial cells and increasing NaCl transport, and reported that the major source of flow-induced O2− is NADPH oxidase (Nox). However, the specific Nox isoform involved is unknown. Of the three isoforms expressed in the kidney—Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4—we hypothesized that Nox4 is responsible for flow-induced O2− production in TALs. Measurable flow-induced O2− production at physiological flow rates of 0, 5, 10, and 20 nl/min was 5 ± 1, 9 ± 2, 36 ± 6, and 66 ± 8 AU/s, respectively. RT-PCR detected mRNA for all three Nox isoforms in the TAL. The order of RNA abundance was Nox2 > Nox4 >>> Nox1. Since all three isoforms are expressed in TALs and pharmacological inhibitors are not selective, we used rats transduced with siRNA and knockout mice. Nox4 siRNA knocked down Nox4 mRNA expression by 63 ± 7% but did not reduce Nox1 or Nox2 mRNA. Flow-induced O2− was 18 ± 9 AU/s in TALs transduced with Nox4 siRNA compared with 77 ± 9 AU/s in tubules transduced with scrambled siRNA. Flow-induced O2− was 81 ± 5 AU/s in Nox2 knockout mice compared with 83 ± 13 AU/s in wild-type mice. In TALs transduced with Nox1 siRNA, flow-induced O2− was 82 ± 7 AU/s. We conclude that Nox4 mediates flow-induced O2− production in TALs.

Keywords: reactive oxygen species, Nox isoforms, luminal flow, kidney

superoxide (O2−) regulates renal function (51, 58). This reactive oxygen species (ROS) favors salt and water retention and has been implicated in salt-sensitive hypertension (23, 30, 49). The thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle (TAL) is the main source of medullary O2− (28, 29, 58), and O2− stimulates NaCl reabsorption in this segment (21, 34, 48). The TAL regulates urinary volume and sodium excretion. Therefore, factors that affect TAL function may lead to inappropriate NaCl retention and result in salt-sensitive hypertension (20, 22, 41).

Flow of urine as it forms along the nephron is highly variable (8, 43). Luminal flow through the TAL normally varies from 0 to 20 nl/min (8, 42, 43). Acute variations in luminal flow are a result of tubuloglomerular feedback (27) and peristalsis of the renal pelvis (8, 43). Luminal flow also varies chronically due to volume changes (1, 42), a high-salt diet (32), hypertension (2, 4, 6, 40, 56), and diabetes (38, 55).

We found that luminal flow stimulates O2− production in TALs by enhancing Na-K-2Cl cotransporter activity (18) and stretching epithelial cells (12), and we determined that the source of O2− is NADPH oxidase (Nox) (19). The Nox family of superoxide-generating enzymes consists of at least seven isoforms of the major catalytic subunit (24). The adult kidney expresses Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 (14). Nox2 mRNA (14, 28) and protein (14, 54) and Nox4 protein (54) have been detected in TALs, whereas thus far Nox1 has only been found in the proximal tubules of the kidney cortex (14, 44). Each of the three isoforms has been implicated in signaling pathways involving O2− stimulation in the kidney (14). However, it is unclear which of these isoforms is involved in flow-stimulated O2−.

Nox4 was originally named Renox because of its high expression in the kidney. We hypothesized that Nox4 is the source of O2− production stimulated by increases in luminal flow. To test this hypothesis, we examined the Nox isoforms expressed in TALs and used knockout animal models and adenoviral delivery of Nox isoform-specific siRNAs to determine which isoforms are involved in flow-stimulated O2−. Our findings indicate that 1) TALs predominantly express Nox2 and Nox4 mRNA, and to a much lower extent Nox1 mRNA; and 2) only Nox4 is involved in flow-stimulated O2− production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and solutions.

Dihydroethidium was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR), RNeasy Plus mini kits and OneStep RT-PCR kits from Qiagen (Valencia, CA), and Nox isoform-specific PCR primers from TIB Molbiol (Adelphia, NJ). Custom oligonucleotides used to construct adenoviruses carrying Nox1- and Nox4-specific siRNA were purchased from Eurofins MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL). The composition of the physiological saline used to perfuse and bathe the TALs was (in mM) 130 NaCl, 2.5 NaH2PO4, 4 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 6 l-alanine, 1 trisodium citrate, 5.5 glucose, 2 calcium dilactate, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 at 37°C. All solutions were adjusted to 290 ± 3 mosmol/kgH2O.

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were maintained on a diet containing 0.22% sodium and 1.1% potassium (Purina, Richmond, IN) for at least 3 days. Male Nox2 knockout (−/−) and C57BL/6J wild-type mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were fed normal rodent chow containing 0.4% sodium. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Henry Ford Hospital in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

RT-PCR.

Separate TAL suspensions from the adenovirus-injected left kidney and noninjected right kidney were prepared as described previously (47). Total RNA was isolated from the suspensions using an RNeasy Plus mini kit and subsequently used for RT-PCR analysis using a OneStep RT-PCR kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Previously published Nox isoform-specific PCR primers (50) were used to assay mRNA expression. Thermal cycler conditions for OneStep RT-PCR were 1) reverse transcription: 30 min at 50°C; 2) HotStarTaq DNA polymerase activation at 95°C for 15 min; 3) cycling at 94°C for 15 s, 60°C for 5 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and 4) final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The total number of cycles used for detection and comparison of relative abundance of Nox isoforms in rat TALs (see Fig. 2) was 35 cycles using 1 μg RNA. However, because of the differences observed in mRNA expression among the three Nox isoforms in TALs, the number of cycles and amount of template RNA were adjusted for the purpose of evaluating knockdown of each particular Nox mRNA by an adenovirally delivered Nox isoform-specific siRNA (see Fig. 3). For Nox1 mRNA knockdown analysis, the PCR primers were 5′-GGAGTCCTCATTTTGTGGGGCAACC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGCACCCGTCTCTCTACAAATCCAGT-3′ (reverse). The total number of cycles used for Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 was 35, 30, and 31, respectively, and the amount of RNA used was 400, 100, and 200 ng. PCR products were visualized on 1.5% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml). Band densities of the expected 560-, 605-, and 409-bp amplicons for Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4, respectively, were analyzed.

Adenovirus construction.

The target (sense) sequence of the siRNA against Nox4 was 5′-CCGTTTGCATCGATACTAA-3′ (bases 1358–1376 in Genbank Accession number NM_053524 for rat Nox4 mRNA). The target sequence of Nox1 siRNA (31) was 5′- AGATCTATTTCTACTGGAT-3′ (bases 1419–1437 in Genbank Accession number NM_053683). A 63-base annealed oligonucleotide siRNA cassette containing the siRNA sequence, a 5′ Afl II overhang, a 3′ Spe I overhang, a transcriptional start, and termination sequence, and a hairpin loop region was inserted into the adenoviral shuttle vector pVQAdMIGHTY, which contains the H1 promoter, and sent to ViraQuest (North Liberty, IA) for adenovirus production. For the negative control, a nonsilencing sequence (Qiagen) was similarly inserted into the shuttle vector for adenovirus construction.

Adenoviral gene delivery.

Rat medullary TALs (mTALs) were transduced in vivo with an adenovirus carrying a Nox4 siRNA (AdNox4siRNA), a Nox1 siRNA (AdNox1siRNA), or a nonsilencing sequence (AdscrsiRNA) as reported previously (35, 36). The left kidney of a rat weighing 85–105 g was exposed via a flank incision and the left renal artery and vein were clamped. Four 20-μl virus injections (4 × 1010 PFU/ml) at a rate of 20 μl/min were made by inserting the needle perpendicular to the renal capsule, parallel to the medullary rays, and directed toward the medulla. Injection points 2.5 mm apart were selected along the longitudinal axis of the kidney. The clamp was released and the kidney was returned to the abdominal cavity. The muscle was sutured and the skin was closed with staples. mTALs were dissected 6–7 days after injection, when maximal knockdown of Nox4 mRNA (63 ± 7%; n = 4, P < 0.003) was observed. For maximal Nox1 mRNA knockdown (59 ± 6%; n = 3, P < 0.01), a total of 100 μl AdNox1siRNA was used, and TALs were dissected 8 days after injection.

Isolation and perfusion of rat TALs.

On the day of the experiment, rats weighing 120–150 g or mice weighing 20–25 g were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (100 and 20 mg/kg body wt ip, respectively). After the abdominal cavity was opened, the left kidney was bathed in ice-cold saline and removed. Sagittal slices were placed in oxygenated physiological saline and mTALs were dissected from the outer medulla under a stereomicroscope at 4–10°C. Tubules measuring 0.5–1.0 mm were transferred to a temperature-regulated chamber and perfused using concentric glass pipettes at 37 ± 1°C as described previously (11). Except for the flow rates used for Fig. 1, we perfused tubules at a rate of 20 nl/min.

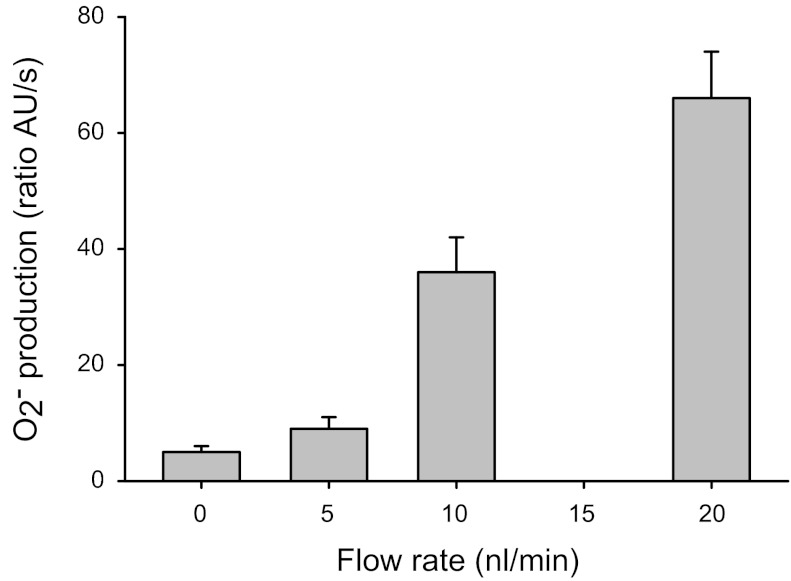

Fig. 1.

Superoxide (O2−) production by the thick ascending limb in response to various luminal flow rates. P < 0.0003 for 10 nl/min and P < 0.0001 for 20 nl/min (compared with 0 nl/min); n = 4 to 6.

Measurement of O2− using dihydroethidium.

Isolated TALs were loaded with 10 μM dihydroethidium in physiological saline for 15 min and then washed in dye-free solution for 20 min. O2− converts dihydroethidium to oxyethidium (10, 57). Oxyethidium and dihydroethidium were excited using 490- and 365-nm light, respectively. Fluorescence emitted between 520–600 nm (oxyethidium) and 400–450 nm (dihydroethidium) was imaged digitally with an image intensifier connected to a CCD camera and recorded with a Metafluor imaging system (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA). Fluorescence from regions of interest was measured every 5 s for 12 measurements. Regression analysis of the fluorescence ratios for each measurement period was performed and differences in slopes were evaluated. An increased rate of change in the oxyethidium/dihydroethidium fluorescence ratio is a measure of increased net O2− production (production − degradation). We will refer to O2− measurements in this study as O2− production.

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SE. Data were evaluated with Student's t-test, taking P < 0.05 as significant.

RESULTS

Physiological luminal flow rates stimulate O2− production.

Physiological luminal flow rates in the TAL can vary from 0 to 20 nl/min. To characterize the relationship between flow and O2− production, we subjected isolated rat TALs to luminal flow rates of 0, 5, 10, and 20 nl/min and measured O2− production. We found it was 5 ± 1 AU/s (n = 6) at 0 nl/min, 9 ± 2 AU/s at 5 nl/min (n = 6), 36 ± 6 AU/s at 10 nl/min (P < 0.0003; n = 4 vs. no flow), and 66 ± 8 AU/s at 20 nl/min (P < 0.0001; n = 4 vs. no flow). Therefore, O2− production increased linearly with flow at rates 5 nl/min and above. However, O2− production at 5 nl/min was no different from basal no flow conditions (Fig. 1). Whether 5 nl/ml represents an actual point at which there is no distinguishable increase in O2− production in response to flow or instead is due to limitations in the method of measuring O2− production is unclear.

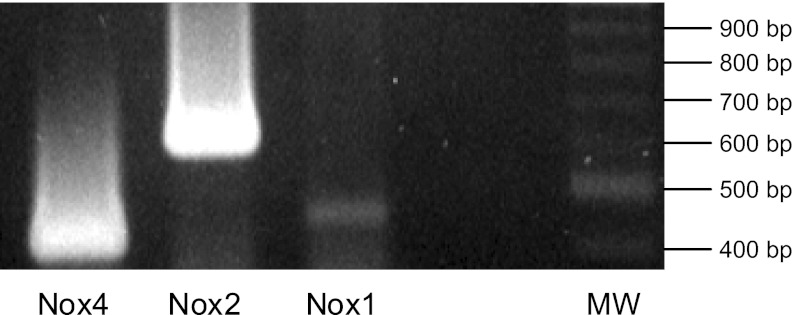

TALs express Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 mRNA.

To identify the Nox isoform(s) involved in flow-stimulated O2−, we first studied which isoforms are expressed in rat TALs by using RT-PCR. We found mRNA of each of the three isoforms in the TAL, although Nox1 was expressed far less than Nox2 or Nox4 (Fig. 2). To demonstrate that RT-PCR could be used as a semiquantitative method, we performed a serial dilution of total RNA to generate a range of starting template from 31 to 250 ng. We found that Nox4 mRNA expression was linear to the amount of RNA template (correlation coefficient = 0.9955). Additionally, because Nox1 was barely detectable in our TAL preparation, we confirmed that the Nox1 PCR primers were working properly by using them with total RNA from a VSMC cell line, in which Nox1 is highly expressed. Therefore, we can conclude that the relative abundance of the three isoforms is Nox2 > Nox4 >>> Nox1.

Fig. 2.

RT-PCR analysis of NADPH oxidase (Nox) isoforms expressed in the thick ascending limb. MW = 100-bp DNA molecular weight ladder.

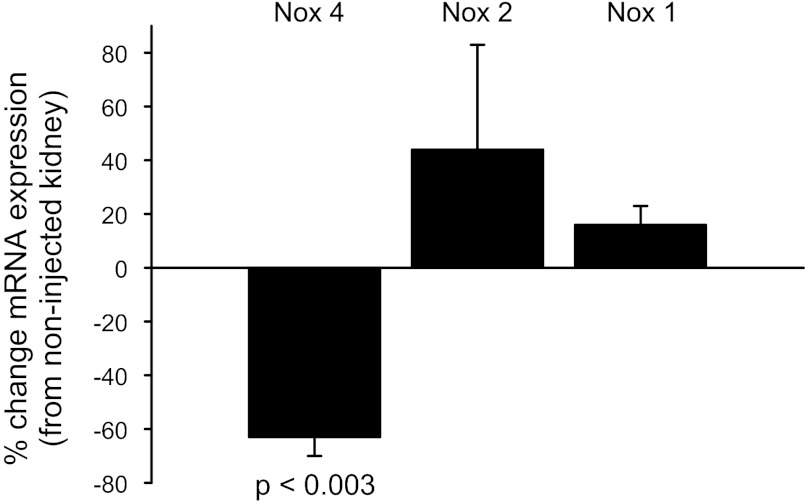

In vivo transduction of TALs with adenovirus carrying Nox4 siRNA specifically and efficiently knocks down Nox4.

Of the three Nox isoforms expressed in TALs, Nox4 is the most highly expressed in the kidney. Therefore, we first chose to study the role of Nox4 in flow-stimulated O2− production. Because there are no Nox4 −/− animal models, we transduced the outer medulla of the rat kidney in vivo with an adenovirus carrying a Nox4 siRNA (AdNox4siRNA). To establish the validity of our siRNA sequence, we transduced TALs with AdNox4siRNA and measured the effect on Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4 mRNA expression (Fig. 3). We found that the Nox4 siRNA knocked down Nox4 mRNA in the TALs from the virus-injected left kidney by 63 ± 7% (P < 0.003) compared with the noninjected right kidney, whereas it had no effect on Nox1 (16 ± 7%) or Nox2 mRNA (44 ± 39%). Therefore, the efficacy and specificity of the Nox4 siRNA were suitable to study the role of Nox4 in flow-induced O2− production.

Fig. 3.

Adenovirus-delivered Nox4 siRNA specificity in the thick ascending limb.

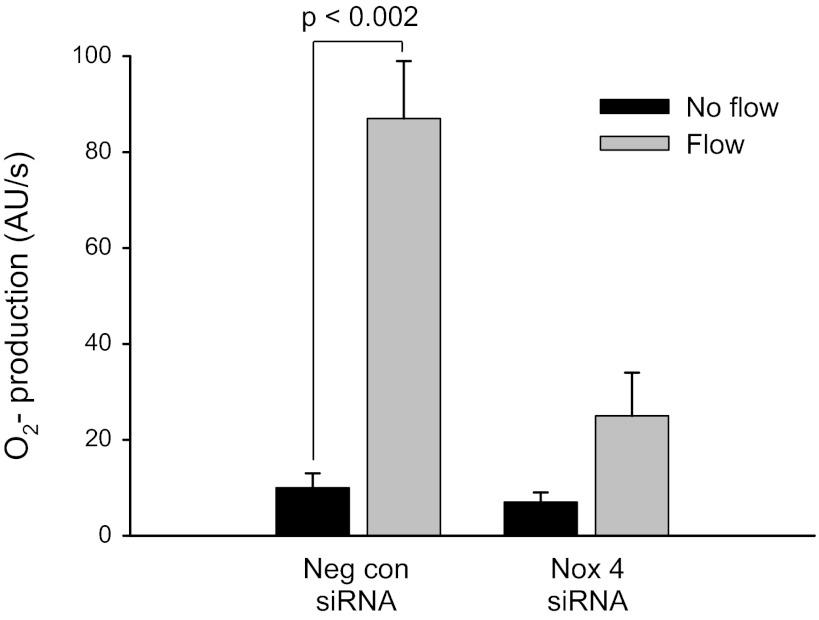

In vivo knockdown of Nox4 inhibits flow-induced O2−.

Next, we examined the effect of knockdown of Nox4 on flow-stimulated O2−. In isolated TALs transduced with a control adenovirus that contained a scrambled nonsilencing sequence (AdscrsiRNA), O2− production increased from 10 ± 3 to 87 ± 12 AU/s (Δ = 77 ± 9 AU/s; P < 0.002; n = 5) when subjected to flow. However, in TALs transduced with the AdNox4siRNA, flow did not significantly increase O2− production (7 ± 2 to 25 ± 9 AU/s; Δ = 18 ± 9 AU/s; n = 6; Fig. 4). Transduction of TALs with AdscrsiRNA did not affect Nox4 mRNA expression. Therefore, knockdown of Nox4 completely inhibited flow-stimulated O2− production.

Fig. 4.

Flow-induced O2− in Nox4 siRNA-transduced thick ascending limbs. Neg con siRNA, transduction with nonsilencing AdscrsiRNA. Nox4 siRNA, transduction with AdNox4siRNA.

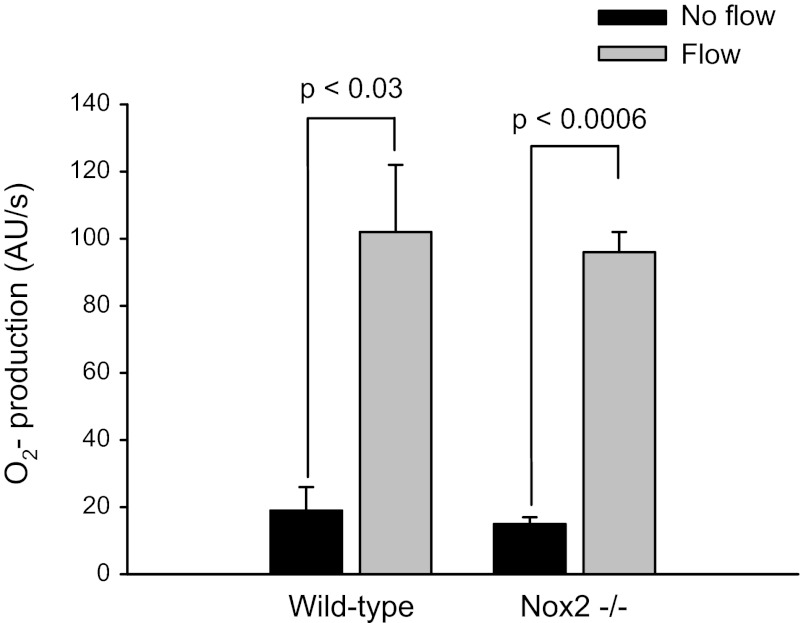

Nox2 is not involved in flow-induced O2−.

We next assessed the possible involvement of Nox2 by measuring flow-stimulated O2− in Nox2 −/− mice (Fig. 5). Initiation of flow increased O2− production from 15 ± 2 to 96 ± 6 AU/s (Δ = 81 ± 5 AU/s; P < 0.0006, n = 4) in Nox2 −/− mice. In wild-type mice luminal flow enhanced O2− production from 19 ± 7 to 102 ± 20 AU/s (Δ = 83 ± 13 AU/s; P < 0.03; n = 3). To determine whether there are compensatory changes in Nox4 expression in Nox2 −/− mice, we compared Nox4 mRNA in wild-type and Nox2 −/− mice. We found that there was no difference. These data indicate that although Nox2 mRNA is highly expressed in TALs, it is not involved in production of O2− in response to luminal flow.

Fig. 5.

Flow-stimulated O2− production in wild-type and Nox2 knockout (−/−) mice.

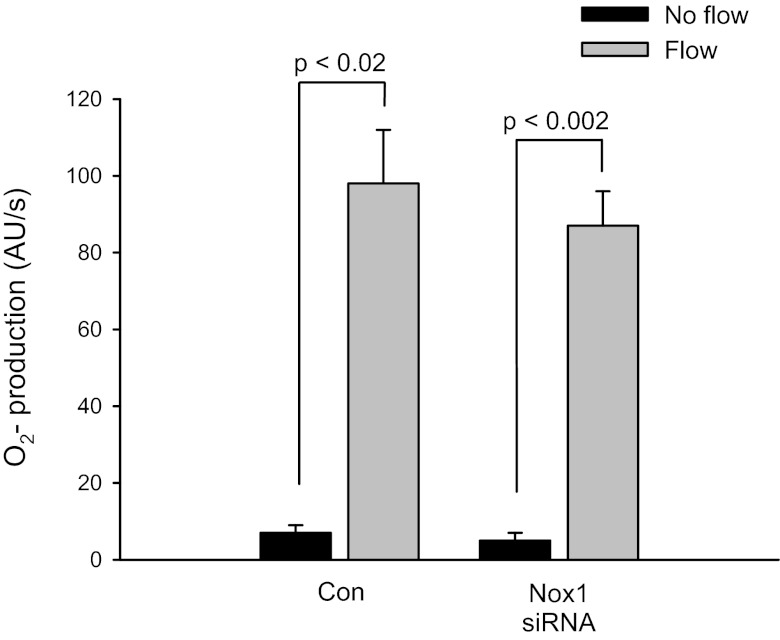

In vivo knockdown of Nox1 does not affect flow-induced O2−.

In endothelial cells a “vicious cycle” in which ROS-activated Nox stimulates Nox-dependent ROS production has been proposed (7). Therefore, it is conceivable that another source of O2−, such as Nox1, which is also present in TALs, could be linked to stimulation of Nox4 to cause enhanced O2− production. To make sure that the flow-induced increase in O2− derived from Nox4 is not coupled to Nox1-stimulated O2−, we tested rat TALs transduced with an adenovirus carrying an siRNA against Nox1 (AdNox1siRNA). The Nox1 siRNA had no effect on flow-stimulated O2− production (Fig. 6). In control experiments (nontransduced TALs), flow increased O2− production from 7 ± 2 to 98 ± 14 AU/s (Δ = 91 ± 13; P < 0.02). In Nox1siRNA-transduced TALs, flow stimulated O2− production to a similar extent (from 5 ± 2 to 87 ± 9 AU/s; Δ = 82 ± 7; P < 0.002). Therefore, knockdown of Nox1 did not affect flow-stimulated O2− production. The Nox1 siRNA knocks down Nox1 mRNA to a similar extent (59 ± 6) as the Nox4 siRNA we used to knockdown Nox4 mRNA (63 ± 7%). Knockdown of Nox1 siRNA does not affect Nox4 or Nox1 expression.

Fig. 6.

Flow-induced O2− in Nox1 siRNA-transduced thick ascending limbs. Con, nontransduced. Nox1 siRNA, transduction with AdNox1siRNA.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that O2− production increases in response to various flow rates. The flow-stimulated increases in O2− at these flow rates are similar to what we observed previously (18). It appears that the break point for response to flow is approximately at 5 nl/min. O2− production at 5 nl/min was not significantly different than at 0 nl/min. Whether this reflects a true maximum flow rate at which O2− is not produced or merely a limitation of our method of measuring low O2− production rates is unclear. However, we estimate that the threshold for triggering O2− production is somewhere around 5 nl/min.

Although previous studies showed that the adult kidney expresses Nox1, Nox2, and Nox4, the isoforms present and their relative abundance in specific segments of the kidney such as the TAL are not well-defined. We were able to detect in TALs the mRNA of each of the three isoforms. This is consistent with others who reported that TALs express Nox2 (14, 28, 44, 54) and Nox4 (14, 44, 54). We also found Nox1 mRNA is present in TALs, albeit to a much lesser extent than Nox2 and Nox4. To our knowledge, we are the first to show that Nox1 mRNA is expressed in the TAL.

Relative band density can be used to deduce relative expression of each mRNA, because the same amount of RNA and number of cycles were used to detect each isoform relative to one another, and the reactions for each isoform were run together and therefore under the same conditions. Furthermore, assuming the same efficiency for each set of primers in the reverse transcription and PCR reactions and given that the PCR products are fairly similar in size, we can conclude that the relative abundance of mRNA in TALs is Nox2 > Nox4 >>> Nox1.

We found the effect of flow on O2− production in TALs transduced with Nox4 siRNA was inhibited, whereas it was not affected in Nox2 −/− mice or in TALs transduced with Nox1 siRNA. These data indicate that the increase in O2− produced in response to increased luminal flow is derived from Nox4 and not Nox2 or Nox1. One might say that identification of Nox4 as the isoform involved in flow-mediated O2− was expected because Nox4, which was originally termed Renox due to its high expression in the kidney (13), is detected in renal tubular epithelium (44). Although high expression of an isoform does not necessarily equate to physiological importance, Nox4 activity has been reported to be determined by mRNA levels (46).

The mechanism whereby Nox4 activity is regulated is unclear. The most characterized isoform of the NADPH oxidase family is the one found in phagocytic cells. It is composed of several subunits: 1) the major catalytic subunit (gp91phox, also known as Nox2) and p22phox, which are integral membrane proteins that form the flavocytochrome b558; and 2) p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, and the small GTPase Rac1, which reside in the cytosol until activated. In the current model of activation, a stimulus phosphorylates and activates p47phox, which organizes the other cytosolic subunits into a complex that translocates to the membrane to allow binding to the flavocytochrome and form an active Nox (3, 25). Nox4 is reportedly constitutively active (46). However, our data suggest that flow acutely stimulates Nox4 activity. Our laboratory also found that angiotensin II rapidly increases O2− in a Nox4-dependent manner. These data are consistent with others who showed that Nox4 is acutely stimulated in proximal tubules (33), mesangial cells (16, 17), and cardiac fibroblasts (5). The mechanism by which Nox4 is upregulated in the TAL rather than other Nox isoforms is unknown. The answer may lie in the differential distribution of Nox isoforms within the cell. The Nox4/p22phox complex has been localized to the endoplasmic reticulum in endothelial cells and epithelial cell lines, whereas the flavocytochrome complex of Nox2 and Nox1 are typically found in the plasma membrane (3). Another possibility is a scheme that involves regulation of mechanosensors, because flow-induced increases in cellular stretch regulate Nox activity in many cell types, including TALs (12) and vascular cells (52).

In endothelial cells, ROS-induced ROS production occurs in which ROS derived from one source stimulates ROS production by a different source to create a “vicious cycle” (7). O2− production in TALs may also represent such a feed-forward system. We showed that flow stimulates O2− production via PKC-α-mediated activation of Nox (19). O2− also activates PKC-α (48), which can further stimulate O2− production. Therefore, it is conceivable that a signaling pathway exists in TALs in which Nox1 or Nox2 is activated by flow to produce O2−, which in turn could stimulate Nox4 to produce even more O2−. However, global knockout of Nox2 in the Nox2 −/− mice had no effect on flow-induced O2−, thus eliminating any possible involvement of Nox2. Transduction of TALs with Nox1 siRNA also had no effect on flow-induced O2−. Therefore, we can rule out the possibility that Nox1 may be involved in flow-stimulated O2−. Additionally, given that Nox1 mRNA is apparently only weakly expressed in TALs and we observed complete inhibition of flow-stimulated O2− in TALs transduced with the Nox4 siRNA, it is unlikely that Nox1 plays any role in flow-induced O2−.

The increase in O2− derived from Nox and its implication in the pathophysiology of diseases such as hypertension and diabetes have been studied extensively in the vasculature (26, 37, 39, 51). The role of Nox4 in the oxidative stress and renal damage associated with diabetes have also been reported (15, 45). However, the effect of O2− in the TAL has not been as widely studied. One group showed that in type 1 diabetes PKC-dependent Nox activation increases O2− production and enhances Na transport (53–55). These reports are consistent with our data that implicate the importance of Nox-derived O2− in conditions in which luminal flow is acutely or chronically enhanced, such as high-salt intake (9, 32), volume expansion (1, 42), and the osmotic diuresis associated with hypertension (2, 4, 6, 40, 56) and diabetes (38, 55).

In summary, we found that luminal flow stimulates Nox4-dependent O2− production by the TAL. The increased Na+ reabsorption caused by enhanced O2− in the TAL may be important in the pathogenesis of hypertension, diabetes, and other diseases associated with Na+ retention and chronically increased flow. Pharmacological agents that target Nox in the TAL may lead to new therapeutic approaches to treating disorders associated with oxidative stress.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL28982, HL70985, and HL90550 to J. L. Garvin.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: N.J.H. performed experiments; N.J.H. analyzed data; N.J.H. and J.L.G. interpreted results of experiments; N.J.H. prepared figures; N.J.H. drafted manuscript; N.J.H. and J.L.G. edited and revised manuscript; N.J.H. and J.L.G. approved final version of manuscript; J.L.G. conception and design of research.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arendshorst WJ, Beierwaltes WH. Renal tubular reabsorption in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 237: F38–F47, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baer PG, Bianchi G, Liliana D. Renal micropuncture study of normotensive and Milan hypertensive rats before and after development of hypertension. Kidney Int 13: 452–466, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 87: 245–313, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chou CL, Marsh DJ. Role of proximal convoluted tubule in pressure diuresis in the rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 251: F283–F289, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cucoranu I, Clempus R, Dikalova A, Phelan PJ, Ariyan S, Dikalov S, Sorescu D. NAD(P)H oxidase 4 mediates transforming growth factor-beta1-induced differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Circ Res 97: 900–907, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DiBona GF, Rios LL. Mechanism of exaggerated diuresis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol 235: 409–416, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dikalova AE, Bikineyeva AT, Budzyn K, Nazarewicz RR, McCann L, Lewis W, Harrison DG, Dikalov SI. Therapeutic targeting of mitochondrial superoxide in hypertension. Circ Res 107: 106–116, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dwyer TM, Schmidt-Nielsen B. The renal pelvis: machinery that concentrates urine in the papilla. News Physiol Sci 18: 1–6, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ellison DH, Velazquez H, Wright FS. Adaptation of the distal convoluted tubule of the rat. Structural and functional effects of dietary salt intake and chronic diuretic infusion. J Clin Invest 83: 113–126, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fink B, Laude K, McCann L, Doughan A, Harrison DG, Dikalov S. Detection of intracellular superoxide formation in endothelial cells and intact tissues using dihydroethidium and an HPLC-based assay. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C895–C902, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garvin JL, Burg MB, Knepper MA. Active NH4+ absorption by the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 255: F57–F65, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garvin JL, Hong NJ. Cellular stretch increases superoxide production in the thick ascending limb. Hypertension 51: 488–493, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geiszt M, Kopp JB, Varnai P, Leto TL. Identification of renox, an NAD(P)H oxidase in kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 8010–8014, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gill PS, Wilcox CS. NADPH oxidases in the kidney. Antioxid Redox Signal 8: 1597–1607, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gorin Y, Block K, Hernandez J, Bhandari B, Wagner B, Barnes JL, Abboud HE. Nox4 NAD(P)H oxidase mediates hypertrophy and fibronectin expression in the diabetic kidney. J Biol Chem 280: 39616–39626, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gorin Y, Ricono JM, Kim NH, Bhandari B, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE. Nox4 mediates angiotensin II-induced activation of Akt/protein kinase B in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F219–F229, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gorin Y, Ricono JM, Wagner B, Kim NH, Bhandari B, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE. Angiotensin II-induced ERK1/ERK2 activation and protein synthesis are redox-dependent in glomerular mesangial cells. Biochem J 381: 231–239, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Flow increases superoxide production by NADPH oxidase via activation of Na-K-2Cl cotransport and mechanical stress in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F993–F998, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hong NJ, Silva GB, Garvin JL. PKC-α mediates flow-stimulated superoxide production in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F885–F891, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ito O, Roman RJ. Role of 20-HETE in elevating chloride transport in the thick ascending limb of Dahl SS/Jr rats. Hypertension 33: 419–423, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Juncos R, Garvin JL. Superoxide enhances Na-K-2Cl cotransporter activity in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F982–F987, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kirchner KA, Crosby BA, Patel AR, Granger JP. Segmental chloride transport in the Dahl-S rat kidney during l-arginine administration. J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1567–1572, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kopkan L, Majid DS. Superoxide contributes to development of salt sensitivity and hypertension induced by nitric oxide deficiency. Hypertension 46: 1026–1031, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lambeth JD. Nox/Duox family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) oxidases. Curr Opin Hematol 9: 11–17, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lambeth JD, Kawahara T, Diebold B. Regulation of Nox and Duox enzymatic activity and expression. Free Radic Biol Med 43: 319–331, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lassegue B, Griendling KK. NADPH oxidases: functions and pathologies in the vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30: 653–661, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leyssac PP, Holstein-Rathlou NH. Effects of various transport inhibitors on oscillating TGF pressure responses in the rat. Pflügers Arch 407: 285–291, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li N, Yi FX, Spurrier JL, Bobrowitz CA, Zou AP. Production of superoxide through NADH oxidase in thick ascending limb of Henle's loop in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F1111–F1119, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li N, Zhang G, Yi FX, Zou AP, Li PL. Activation of NAD(P)H oxidase by outward movements of H+ ions in renal medullary thick ascending limb of Henle. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F1048–F1056, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meng S, Cason GW, Gannon AW, Racusen LC, Manning RD., Jr Oxidative stress in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension 41: 1346–1352, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Menshikov M, Plekhanova O, Cai H, Chalupsky K, Parfyonova Y, Bashtrikov P, Tkachuk V, Berk BC. Urokinase plasminogen activator stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via redox-dependent pathways. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 801–807, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mozaffari MS, Jirakulsomchok S, Shao ZH, Wyss JM. High-NaCl diets increase natriuretic and diuretic responses in salt-resistant but not salt-sensitive SHR. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F890–F897, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. New DD, Block K, Bhandhari B, Gorin Y, Abboud HE. IGF-I increases the expression of fibronectin by Nox4-dependent Akt phosphorylation in renal tubular epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 302: C122–C130, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ortiz PA, Garvin JL. Superoxide stimulates NaCl absorption by the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F957–F962, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Plato CF, Varela M, Garvin JL. An in vivo method for adenovirus-mediated transduction of thick ascending limbs. Kidney Int 63: 1141–1149, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Wang D, Garvin JL. Gene transfer of eNOS to the thick ascending limb of eNOS-KO mice restores the effects of l-arginine on NaCl absorption. Hypertension 42: 674–679, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Paravicini TM, Touyz RM. Redox signaling in hypertension. Cardiovasc Res 71: 247–258, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pollock CA, Lawrence JR, Field MJ. Tubular sodium handling and tubuloglomerular feedback in experimental diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F946–F952, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rajagopalan S, Kurz S, Munzel T, Tarpey M, Freeman BA, Griendling KK, Harrison DG. Angiotensin II-mediated hypertension in the rat increases vascular superoxide production via membrane NADH/NADPH oxidase activation. Contribution to alterations of vasomotor tone. J Clin Invest 97: 1916–1923, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Roman RJ. Pressure-diuresis in volume-expanded rats. Tubular reabsorption in superficial and deep nephrons. Hypertension 12: 177–183, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roman RJ, Kaldunski ML. Enhanced chloride reabsorption in the loop of Henle in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension 17: 1018–1024, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sakai T, Craig DA, Wexler AS, Marsh DJ. Fluid waves in renal tubules. Biophys J 50: 805–813, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schmidt-Nielsen B. The renal concentrating mechanism in insects and mammals: a new hypothesis involving hydrostatic pressures. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 268: R1087–R1100, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schreck C, O'Connor PM. NAD(P)H oxidase and renal epithelial ion transport. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R1023–R1029, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sedeek M, Callera G, Montezano A, Gutsol A, Heitz F, Szyndralewiez C, Page P, Kennedy CR, Burns KD, Touyz RM, Hebert RL. Critical role of Nox4-based NADPH oxidase in glucose-induced oxidative stress in the kidney: implications in type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F1348–F1358, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Serrander L, Cartier L, Bedard K, Banfi B, Lardy B, Plastre O, Sienkiewicz A, Forro L, Schlegel W, Krause KH. NOX4 activity is determined by mRNA levels and reveals a unique pattern of ROS generation. Biochem J 406: 105–114, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Silva GB, Garvin JL. Akt1 mediates purinergic-dependent NOS3 activation in thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F646–F652, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Silva GB, Ortiz PA, Hong NJ, Garvin JL. Superoxide stimulates NaCl absorption in the thick ascending limb via activation of protein kinase C. Hypertension 48: 467–472, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Swei A, Lacy F, DeLano FA, Parks DA, Schmid-Schonbein G. A mechanism of oxygen free radical production in the Dahl hypertensive rat. Microcirculation 6: 179–187, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Szocs K, Lassegue B, Sorescu D, Hilenski LL, Valppu L, Couse TL, Wilcox JN, Quinn MT, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK. Upregulation of Nox-based NAD(P)H oxidases in restenosis after carotid injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 21–27, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilcox CS. Reactive oxygen species: roles in blood pressure and kidney function. Curr Hypertens Rep 4: 160–166, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wolin MS, Ahmad M, Gupte SA. The sources of oxidative stress in the vessel wall. Kidney Int 67: 1659–1661, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yang J, Lane PH, Pollock JS, Carmines PK. PKC-dependent superoxide production by the renal medullary thick ascending limb from diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F1220–F1228, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yang J, Lane PH, Pollock JS, Carmines PK. Protein kinase C-dependent NAD(P)H oxidase activation induced by type 1 diabetes in renal medullary thick ascending limb. Hypertension 55: 468–473, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yang J, Pollock JS, Carmines PK. NADPH oxidase and PKC contribute to increased Na transport by the thick ascending limb during type 1 diabetes. Hypertension 59: 431–436, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang Y, Mircheff AK, Hensley CB, Magyar CE, Warnock DG, Chambrey R, Yip KP, Marsh DJ, Holstein-Rathlou NH, McDonough AA. Rapid redistribution and inhibition of renal sodium transporters during acute pressure natriuresis. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 270: F1004–F1014, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhao H, Kalivendi S, Zhang H, Joseph J, Nithipatikom K, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Superoxide reacts with hydroethidine but forms a fluorescent product that is distinctly different from ethidium: potential implications in intracellular fluorescence detection of superoxide. Free Radic Biol Med 34: 1359–1368, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zou AP, Li N, Cowley AW., Jr Production and actions of superoxide in the renal medulla. Hypertension 37: 547–553, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]