Abstract

Myosin 1e (myo1e) is an actin-dependent molecular motor that plays an important role in kidney functions. Complete knockout of myo1e in mice and Myo1E mutations in humans are associated with nephrotic syndrome and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. In this paper, we tested the hypothesis that myo1e is necessary for normal functions of glomerular visceral epithelial cells (podocytes) using podocyte-targeted knockout of myo1e. Myo1e was selectively knocked out in podocytes using Cre-mediated recombination controlled by the podocin promoter. Myo1e loss from podocytes resulted in proteinuria, podocyte foot process effacement, and glomerular basement membrane disorganization. Our findings indicate that myo1e expression in podocytes is necessary for normal glomerular filtration and that podocyte defects are likely to represent the primary pathway leading to glomerular disease associated with Myo1E mutations.

Keywords: myosin, podocyte, proteinuria

one of the main functions performed by the kidney is regulation of protein excretion in the urine. In the healthy kidney, glomerular filtration barrier retains the majority of high molecular weight proteins. Glomerular disorders, both inherited and acquired, are associated with proteinuria, which, if not reversed, leads to end-stage renal disease. Genetic studies and experiments using knockout mouse models have implicated many cytoskeletal proteins, particularly those associated with the actin cytoskeleton, in regulation of glomerular permeability (5, 6, 23). One of the cytoskeletal proteins that contribute to the normal functioning of the glomerular filtration barrier is an actin-dependent molecular motor myosin 1e (myo1e). Myo1e-null mice developed by our lab exhibit extensive proteinuria, indicating that myo1e plays a central role in regulating glomerular filtration (12). Two recent genetic studies also identified an association between mutations in the human Myo1E gene and the autosomal recessive nephrotic syndrome (13, 15). These findings underscore the importance of myo1e to normal glomerular functions.

A key question that remains unanswered by the genetic studies is which specific cell type(s) in the glomerulus requires myo1e activity and represents the primary site of injury in the myo1e-null glomeruli. Glomerular filtration apparatus is composed of three main components: endothelial cells of glomerular capillaries, glomerular visceral epithelial cells (podocytes) covering the surface of the capillaries, and glomerular basement membrane (GBM), which is secreted by both endothelial and epithelial cells. In addition to the endothelial and epithelial cells of the glomerulus, another cellular component that contributes to normal glomerular development and functions is glomerular mesangium, composed of contractile cells that shape capillary loops and maintain the overall architecture of the capillary tuft (16). Injury or abnormal development of the cellular components of the glomerulus, particularly podocytes and endothelial cells, results in proteinuria (7, 21).

Since myo1e is highly expressed in podocytes and the phenotype of myo1e-null mice is consistent with a podocyte defect, we set out to test the hypothesis that myo1e expression is necessary for normal podocyte development and functions. As a direct test of this hypothesis, we created a mouse model that allows selective inactivation of myo1e in podocytes through Cre-mediated recombination. Characterization of glomerular functions and organization in this mouse model show that podocyte-targeted loss of myo1e causes proteinuria and ultrastructural defects of podocytes and GBM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal studies.

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the protocols approved by the SUNY Upstate Committee for Humane Use of Animals. Complete myo1e-knockout mice and conditional myo1e-knockout mice (previously described in Ref. 12) were backcrossed to C57bl/6 mice for 12 generations. Conditional knockout (“floxed”) mice were then crossed with NPHS2-Cre (Podo-Cre) mice (14) on C57bl/6 background. The following PCR primers were used for genotyping: Myo1e A (TCATGTGTAGCCCAAGCTCACC), Myo1e B (TTCCGCTTACGGTGGAAATG), Myo1e C (ACTCATTCTGTCATCTGACTCCACC), Cre For (GCATAACCAGTGAAACAGCATTGCTG), Cre Rev (GGACATGTTCAGGGATCGCCAGGCG).

Albumin concentration in mouse urine samples was determined using SDS-PAGE with bovine serum albumin standards followed by gel densitometry using ImageJ software. Creatinine concentration was measured using Creatinine Companion kit (Exocell).

Antibodies.

The following primary antibodies were used for immunostaining: rabbit anti-myo1e (20), mouse anti-synaptopodin G1D4 (Meridian Life Science), rat anti-PECAM-1 (BD Pharmingen), mouse anti-desmin (BD Pharmingen), rabbit anti-α-actinin 4 (MABT144, Millipore), rabbit anti-myo2a (Biomedical Technologies), rabbit anti-podocin (Alpha Diagnostics), rabbit anti-integrin α3 (AB1920, Millipore), rabbit anti-phospho-nephrin (22).

Immunohistochemistry, histology, and electron microscopy.

For immunostaining, fresh kidneys were frozen in OCT and sectioned. Cryosections were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, permeabilized using 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS for 3 min, and processed for immunofluorescence or immunohistochemical staining. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using Vector Labs Vectastain Elite ABC anti-rabbit kit following the manufacturer's instructions. Histological staining was performed on sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded kidneys. Images of immunofluorescently labeled kidney sections were collected using a Perkin-Elmer UltraView VoX Spinning Disc Confocal system mounted on a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope. Images of histology slides were collected using a color Spot camera on a Nikon Eclipse TE-2000 microscope. Kidney fixation and processing for electron microscopy were performed as previously described (12). Morphometry on kidney sections was performed using ImageJ software. Five to fifteen micrographs per animal (obtained from different glomeruli) were included in the analysis, and four animals were analyzed for each genotype. GBM in each electron micrograph was manually outlined in ImageJ to determine its area. The total area of all regions of the basement membrane present in each micrograph was divided by the total length of the basement membrane (measured by drawing a line through the center of each basement membrane segment) to determine its average thickness. Foot process number was manually counted and divided by the length of the basement membrane.

RESULTS

Generation of mice with the podocyte-targeted knockout of Myo1e.

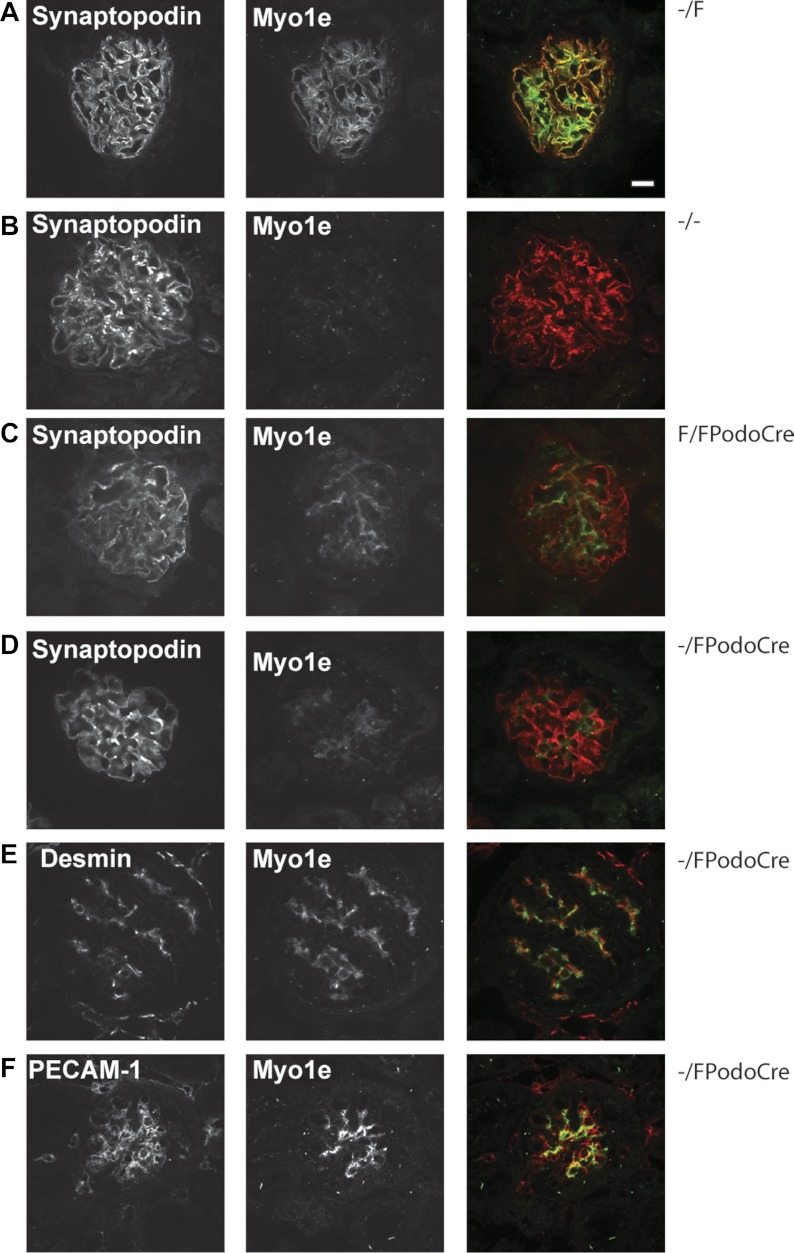

We previously generated mice containing a conditional (floxed) allele of Myo1e so that Myo1e gene could be removed by Cre-mediated homologous recombination (12). In the previously published study (12), mice carrying floxed Myo1e allele were crossed with mice that expressed Cre in the germline, allowing us to obtain the complete Myo1e knockout (Myo1e-null or −/− mice). In the current study, we used mice that express Cre recombinase under the control of podocin promoter (14) to achieve podocyte-specific removal of Myo1e (Fig. 1). Loss of myo1e from podocytes was verified using immunostaining of mouse kidney sections with the previously characterized myo1e-specific antibodies (Fig. 2) (4). Mice carrying at least one wild-type copy of Myo1e (Myo1e−/F) exhibited normal myo1e expression, with the majority of myo1e colocalizing with the podocyte marker synaptopodin (Fig. 2A). Most mice with the podocyte-targeted Myo1e knockout (Myo1eF/FPodoCre) showed no expression of myo1e in podocytes (Fig. 2C). However, some of the mice carrying two conditional alleles of Myo1e (Myo1eF/FPodoCre) exhibited incomplete removal of Myo1e from podocytes, as indicated by a significant amount of glomerular immunostaining for myo1e in such animals (data not shown). To increase the efficiency of myo1e removal from podocytes, we generated mice that carried one copy of the conditional myo1e allele and one copy of the myo1e-null allele (Myo1e−/FPodoCre) so that only one copy of the gene would need to be removed by the Cre recombinase. Mice of this genotype exhibited a highly reproducible loss of Myo1e immunoreactivity from podocytes (Fig. 2). Some residual myo1e staining was observed in the glomeruli of animals with the podocyte-specific Myo1e knockout (Fig. 2). This residual myo1e labeling was observed primarily in cells positive for the smooth muscle marker desmin but also showed some colocalization with cells expressing the endothelial marker PECAM-1 (Fig. 2, E and F). As previously reported (12), myo1e-null mice showed no myo1e staining in the glomeruli (Fig. 2B). Thus, as anticipated, PodoCre-mediated recombination disrupted myo1e expression in podocytes. Unexpectedly, it also revealed a low level of myo1e expression in other glomerular cell populations, particularly in mesangial cells, which are positive for desmin.

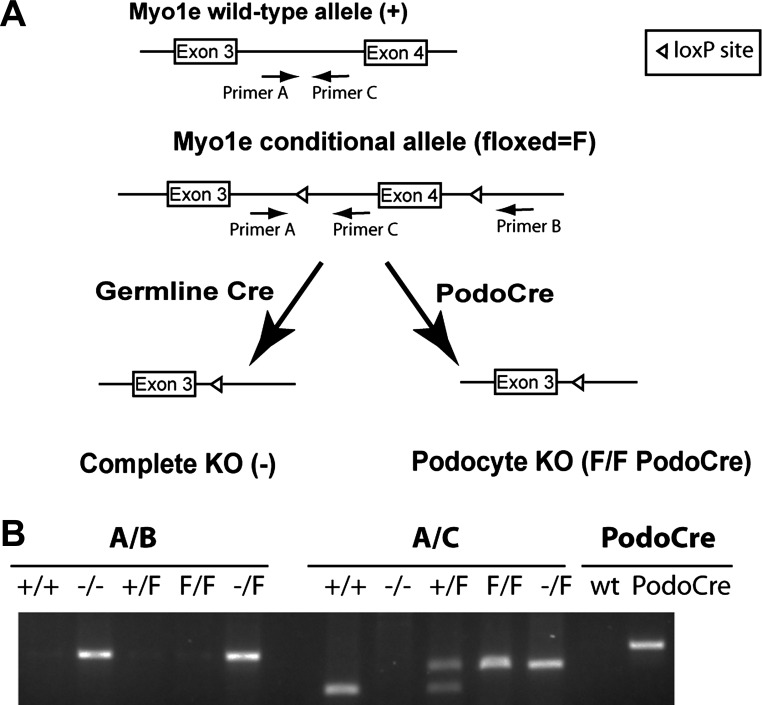

Fig. 1.

Generation and genotyping of mice with the podocyte-targeted myosin 1e (Myo1e) knockout. A: gene targeting and genotyping strategy to achieve constitutive or podocyte-specific Myo1e knockout. Introduction of loxP sites into the mouse Myo1e gene produced a conditional (also called floxed, F) allele of Myo1e. Locations of genotyping primers (A, B, C) are indicated by arrows. Cre-mediated recombination between the loxP sites in the germline was used to obtain constitutive knockout mice. In these mice, exon 4 of Myo1e has been completely excised in all tissues, resulting in creation of a premature stop-codon near the NH2 terminus of myo1e protein in all cell types (labeled as complete knockout or Myo1e−/−). Combining a conditional Myo1e allele with a transgene that encodes Cre recombinase under the control of podocin promoter resulted in removal of exon 4 only from podocytes (podocyte-targeted knockout, labeled as Myo1eF/FPodoCre). B: genotyping of myo1e-knockout mice. Primers shown in A were used to amplify PCR fragments with mouse genomic DNA as a template. Primer pair A/B produces a 260-bp band only when using DNA from the complete knockout as a template, primer pair A/C produces a 240-bp band using DNA from mice carrying the conditional (floxed) allele, a 140-bp band using DNA from mice carrying the wild-type allele, and no product using DNA from the complete knockout mice. A separate set of primers was used to verify the presence of the Podo-Cre transgene.

Fig. 2.

Localization of myo1e in glomeruli of control and myo1e-knockout mice. Cryosections of kidneys from control (Myo1e–/F; A), myo1e-null (B), and podocyte-specific knockout (Myo1eF/FPodoCre and Myo1e−/FPodoCre; C–F) adult mice double-labeled with antibodies against myo1e (green in the merged images) and markers of podocytes (synaptopodin; A–D), mesangial cells (desmin; E), or endothelial cells (PECAM-1; F) (shown in red in the merged images). In mice with the podocyte-targeted myo1e knockout, myo1e labeling is not observed in podocytes (C, D), unlike control mice (A); however, residual myo1e is colocalized with the desmin-positive mesangial cells (E) and, to a lesser extent, with PECAM-1-positive endothelial cells. Bar = 10 μm.

Characterization of renal filtration in mice with the podocyte-specific Myo1e knockout.

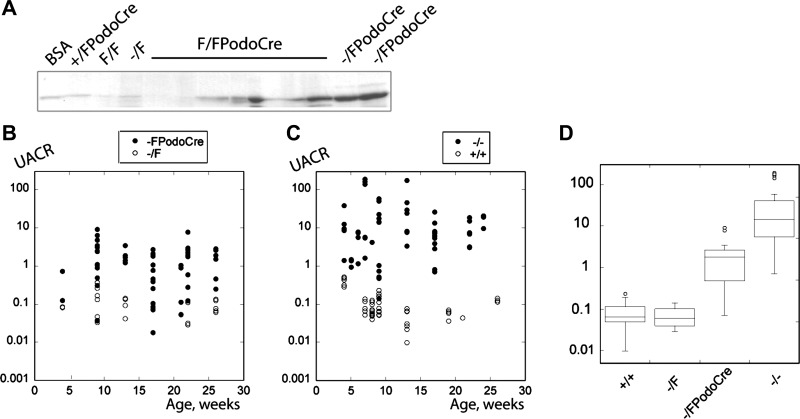

To determine how the loss of myo1e from podocytes affected kidney functions, we measured urinary albumin excretion in control (Myo1e−/F) and podocyte-specific knockout (Myo1e−/FPodoCre) mice. Myo1e−/FPodoCre mice developed moderate proteinuria by 8 wk of age, while control mice had normal glomerular filtration with no evidence of albuminuria up to 6 mo of age (Fig. 3, A and B). We also evaluated proteinuria in mice of the Myo1eF/FPodoCre genotype (Fig. 3A). Many of these animals developed proteinuria by 8 wk of age. However, those mice that retained myo1e expression in podocytes, as verified by immunostaining (data not shown), did not exhibit proteinuria; some of these animals maintained normal urinary protein excretion up to the end of the screening period (6–8 mo of age).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of proteinuria in myo1e-knockout mice. A: urine samples (5 μl) collected from mice with the podocyte-targeted knockout of myosin 1e (Myo1eF/FPodoCre and Myo1e−/FPodoCre) or from control mice (Myo1e+/FPodoCre, Myo1eF/F, Myo1e−/F) and a sample of BSA (first lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Note that most urine samples from mice with the podocyte-specific knockout of Myo1e contain a prominent albumin band. B, C: urinary albumin:creatinine ratio measured using urine samples collected at various time points from mice of indicated genotypes. Each dot represents a single urine sample. D: box-and-whiskers plots of the urinary albumin:creatinine ratio measured using urine samples from 2- to 6-mo-old mice of indicated genotypes. Horizontal line within each box indicates the median for each group, boxes correspond to the 25–75 percentile range, and outliers are shown as open circles.

Comparison of proteinuria levels in mice with the complete and podocyte-targeted myo1e knockout.

While urinary albumin excretion in podocyte-targeted myo1e-knockout mice was elevated compared with the controls, the extent of proteinuria in this mouse model was fairly modest, with only an order of magnitude increase over the baseline level. Previously, we observed that albumin excretion in mice with the complete Myo1e knockout (Myo1e−/−) on the mixed 129/C57bl/6 genetic background was several orders of magnitude higher than in controls (Myo1e+/+) (12). Since all mice in the present study were backcrossed to the C57bl/6 background, which sometimes ameliorates kidney disease (1, 4), we measured proteinuria in mice with the complete myo1e knockout (Myo1e−/−) on the C57bl/6 background for comparison with the podocyte-specific knockout mice. Even when the influence of the genetic background was equalized by backcrossing to C57bl/6, myo1e-null mice (Myo1e−/−) consistently exhibited much higher levels of proteinuria than mice with the podocyte-targeted myo1e knockout (Fig. 3).

Analysis of glomerular ultrastructure in mice with the podocyte-targeted myo1e knockout.

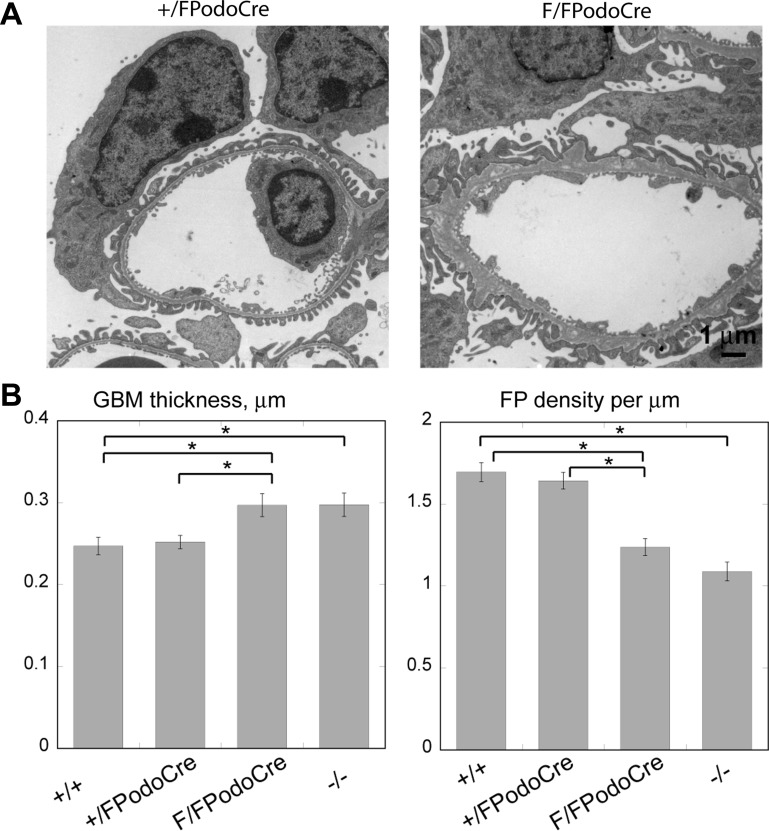

To determine the effects of myo1e removal from podocytes on glomerular ultrastructure, kidney sections from 2- and 4-mo-old mice were analyzed by electron microscopy. These studies were conducted using mice of the Myo1e−/− and Myo1eF/FPodoCre genotypes as well as appropriate controls (Myo1e+/+ and Myo1e+/FPodoCre). To limit the ultrastructural analysis to the animals with the successful podocyte-targeted knockout of myo1e, only mice exhibiting detectable levels of proteinuria were used for the analysis of the Myo1eF/FPodoCre genotype. Pronounced podocyte foot process effacement and basement membrane disorganization and thickening were observed in the 4-mo-old mice with either podocyte-targeted or global myo1e knockout. Since the extent of the changes in the basement membrane and foot process organization was highly variable among individual glomeruli and glomerular segments in each animal, we performed morphometric analysis of the electron micrographs to measure the average basement membrane thickness (area divided by length) and the average number of foot processes per unit length of the basement membrane. Average membrane thickness was increased and foot process number was decreased compared with the control mice (Fig. 4). Some regions of the basement membrane exhibited characteristic electron-lucent or “moth-eaten” areas, similar to those observed in the myo1e-null mice and human patients with Myo1E mutations (12, 13), and the overall outline of the basement membrane was jagged and uneven, in contrast to the smooth basement membrane of control animals. In addition, microvillous transformation of podocytes, which represents one of the hallmarks of podocyte damage, was observed in the myo1e-knockout mice. At 2 mo of age, only a few areas of foot process effacement and GBM thickening were observed in mice with the podocyte-targeted myo1e knockout. This was in contrast to the myo1e-null mice, which exhibited widespread foot process effacement and GBM alterations at 2 mo (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of glomerular ultrastructure in myo1e-knockout mice. A: representative transmission electron micrographs of glomeruli of 4-mo-old mice with the podocyte-specific knockout of myo1e (Myo1eF/FPodoCre) and control mice (Myo1e+/FPodoCre). Note foot process effacement and uneven outlines of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) in the knockout mice. B: morphometric analysis of GBM thickness and foot process density using electron micrographs obtained from 4-mo-old mice. Micrographs of multiple glomeruli obtained from 4 mice for each genotype were used for image analysis. Data shown represent means ± SE. *Statistically significant differences determined using Student's t-test (P < 0.001).

Histological characterization of myo1e-knockout kidneys.

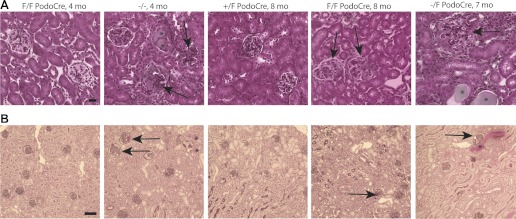

With routine histology staining, including hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid Schiff, and trichrome, kidneys of mice with the podocyte-targeted myo1e knockout appeared mostly normal up to 6 mo. At the age of 7–8 mo, some sclerotic glomeruli were observed, along with a few proteinaceous casts indicative of persistent proteinuria (Fig. 5). Mice with the complete myo1e knockout exhibited more pronounced and widespread abnormalities at an earlier age, with multiple sclerotic glomeruli and tubular casts present by 4 mo (Fig. 5). Control mice carrying at least one functional copy of the myo1e allele did not show any signs of glomerular pathology at the ages examined (up to 10 mo).

Fig. 5.

Histological analysis of kidneys of myo1e-knockout mice. Paraffin-embedded kidney sections obtained from myo1e-null mice (Myo1e−/−), podocyte-targeted knockout mice (Myo1eF/FPodoCre, Myo1e−/FPodoCre), and control mice (Myo1e+/FPodoCre) at the indicated ages were stained using Masson Trichrome (A) or periodic acid Schiff (B). Four-month-old myo1e-null mice had multiple sclerotic glomeruli (arrows) and protein casts (*) while kidneys of 4-mo-old podocyte-targeted knockout mice appeared mostly normal. At 8 mo, kidneys of podocyte-targeted knockout mice contained a small number of sclerotic glomeruli (arrows) while control mouse kidneys appeared normal. Scale bars = 20 μm in A, 100 μm in B.

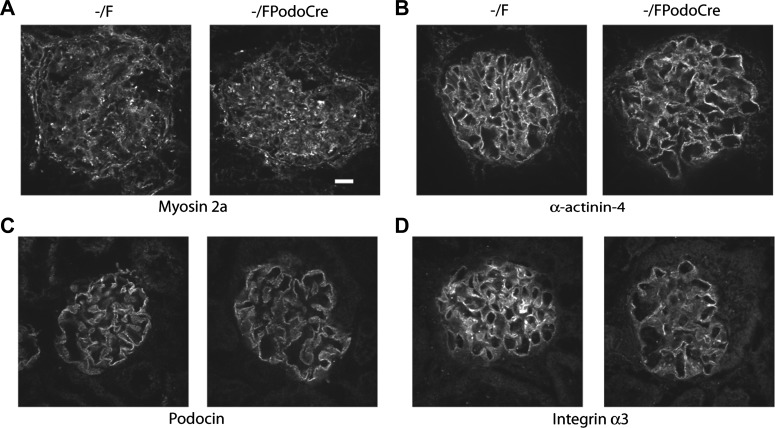

Analysis of the components of podocyte cytoskeleton and cell adhesion complexes in myo1e-knockout kidneys.

Since the abnormalities observed in the myo1e-knockout mice could be caused by defects in the podocyte actin cytoskeletal organization, slit diaphragm structure, or adhesion to the basement membrane, we examined expression and localization of several key markers of the podocyte cytoskeleton and cell adhesion complexes. Expression and localization patterns of the slit diaphragm marker podocin, podocyte-specific cell adhesion receptor α3 integrin, and several key components of the podocyte actin cytoskeleton, including synaptopodin, nonmuscle myosin 2a (encoded in humans by the MYH9 gene), and α-actinin-4, were similar in myo1e-knockout mice and control animals (Figs. 1 and 6). We also examined the extent of nephrin phosphorylation as a marker for signaling pathways affecting podocyte cytoskeletal organization (22). No changes in nephrin phosphorylation were observed in the myo1e-knockout mice (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Immunohistochemical analysis of podocyte markers in the glomeruli of myo1e-knockout mice. Cryosections of kidneys from control (Myo1e−/F) and podocyte-targeted knockout (Myo1e−/FPodoCre) mice were stained using antibodies against nonmuscle myosin 2a (A), α-actinin-4 (B), podocin (C), and integrin α3 (D). Expression and localization of these markers were similar in control and knockout mice. Bar = 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

The key finding of this study is that selective removal of myo1e from podocytes is sufficient to induce proteinuria. Mice with the podocyte-targeted knockout of myo1e also exhibit defects in the glomerular ultrastructure, including foot process effacement and thickening and delamination of GBM. These ultrastructural changes are similar to those observed in the myo1e-null mice and in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis patients with Myo1E mutations (12, 13). Thus, the loss of myo1e from podocytes is sufficient to disrupt glomerular filtration and to induce severe structural defects in the glomerulus.

While mice with the podocyte-targeted knockout of myo1e exhibit defects in protein filtration, the timing of onset and the extent of proteinuria are less dramatic than in myo1e-null mice. Proteinuria in mice with the podocyte-targeted knockout of myo1e develops by 2 mo of age while myo1e-null mice develop proteinuria by 1 mo of age. This delay may be due to the timing of myo1e removal using Cre recombinase expressed under the control of podocin promoter. Since podocin promoter activity is induced fairly late in the glomerular development, during capillary loop stage (14), in the podocyte-targeted knockout mice expression of myo1e may persist up to a fairly late stage in podocyte differentiation. The timing of myo1e loss in the podocyte-targeted mouse model may also explain the difference in the observed proteinuria level. If myo1e plays an important role both in the development of early podocyte precursors and in the functions of mature podocytes, myo1e-null mice would exhibit more severe glomerular defects than mice that lose myo1e expression in podocytes during capillary loop stage.

Moreover, myo1e may be necessary not only for podocyte functions but also for the normal physiological functions of other cells in the glomerulus. Since we observed myo1e expression in mesangial cells, it is possible that myo1e may contribute to mesangial cell migration to glomeruli during the development or to normal mesangial cell functions in the mature glomeruli. To address this possibility, we examined the number and morphology of mesangial cells in the kidneys of myo1e-knockout mice. Glomeruli of both myo1e-null and wild-type mice at various ages (newborn, 7-day-old, 21-day-old, 3-mo-old) contained desmin-positive mesangial cells (data not shown) and no mesangial cell abnormalities were apparent from electron micrographs of myo1e-null glomeruli. Therefore, while we cannot exclude the possibility that the loss of myo1e may negatively affect mesangial cell functions, no obvious evidence of mesangial cell loss or defects in the myo1e-null mice was found in this study.

In our study, the severity of proteinuria correlated with the prevalence of histological abnormalities in the kidneys. Mice with the complete knockout of myo1e exhibited widespread glomerulosclerosis by 4 mo of age while mice with the podocyte-specific knockout of myo1e showed first signs of glomerulosclerosis by 8 mo of age. The delayed onset and decreased severity of glomerulosclerosis were in contrast to the ultrastructural glomerular changes, which were highly prevalent by 4 mo even in the podocyte-specific model. Our findings suggest that while the loss of glomerular integrity as a result of myo1e removal from podocytes is rapidly manifested in proteinuria and defects in glomerular ultrastructure, histological signs of glomerulosclerosis develop only with nephrotic range proteinuria and/or with prolonged exposure to moderate proteinuria.

Multiple studies showed that the actin cytoskeleton plays a key role in maintaining podocyte foot process architecture and slit diaphragm organization. Actin cytoskeleton-associated proteins that have been linked to glomerular functions include actin bundling and regulatory proteins (α-actinin-4, synaptopodin, cofilin) (3, 6, 8, 11), adaptor proteins (Nck, CD2AP) that regulate podocyte cytoskeletal organization and link slit diaphragm components to the actin cytoskeleton (10, 19, 22, 24), and actin-dependent motor proteins (myosins). Nonsense mutations in the gene encoding nonmuscle myosin 2A (MYH9) result in disorders that affect a number of organ systems and include glomerular manifestations (17, 18), while the podocyte-targeted knockout of Myo2a renders mice susceptible to adriamycin-induced nephropathy (9). Knockout of myo1e causes nephrotic syndrome in mice while another class I myosin, myo1c, has recently been implicated in regulation of Neph1 localization in podocytes (2). The findings of the current study further elucidate the importance of myosin motors to podocyte functions and provide the first direct evidence that myo1e activity in podocytes is indispensable for normal glomerular filtration.

We examined the effects of myo1e knockout on the key components of the podocyte cytoskeleton and cell adhesion complexes (synaptopodin, α-actinin-4, myosin 2a, integrin α3, podocin) and found no changes in the expression or localization of these markers. Thus, glomerular abnormalities observed in mice lacking myo1e do not appear to be a direct result of changes in the expression of podocyte cytoskeletal or cell adhesion proteins. These findings suggest that the mechanism linking the loss of myo1e to glomerular filtration defects may involve subtle changes in the regulation of podocyte adhesion and cytoskeletal organization, rather than the loss of expression of specific podocyte proteins.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Nephcure Foundation Junior Investigator Award and National Institutes of Health award 1R01DK083345.

Present address of C. V. Encina: USAF 81st Diagnostics & Therapeutics Squadron, Keesler AFB Mississippi.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.E.C., C.V.E., L.R.S., and M.K. performed experiments; S.E.C., C.V.E., L.R.S., A.H.T., and M.K. analyzed data; S.E.C., L.B.H., and M.K. edited and revised manuscript; C.V.E., A.H.T., L.B.H., and M.K. interpreted results of experiments; M.K. conception and design of research; M.K. prepared figures; M.K. drafted manuscript; M.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Howard Wynder (Histology and Microscopy Core, Washington University in St. Louis) for processing mouse kidney samples for electron microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andrews KL, Mudd JL, Li C, Miner JH. Quantitative trait loci influence renal disease progression in a mouse model of Alport syndrome. Am J Pathol 160: 721–730, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arif E, Wagner MC, Johnstone DB, Wong HN, George B, Pruthi PA, Lazzara MJ, Nihalani D. Motor protein Myo1c is a podocyte protein that facilitates the transport of slit diaphragm protein Neph1 to the podocyte membrane. Mol Cell Biol 31: 2134–2150, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ashworth S, Teng B, Kaufeld J, Miller E, Tossidou I, Englert C, Bollig F, Staggs L, Roberts IS, Park JK, Haller H, Schiffer M. Cofilin-1 inactivation leads to proteinuria–studies in zebrafish, mice and humans. PLos One 5: e12626, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baleato RM, Guthrie PL, Gubler MC, Ashman LK, Roselli S. Deletion of CD151 results in a strain-dependent glomerular disease due to severe alterations of the glomerular basement membrane. Am J Pathol 173: 927–937, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Faul C, Asanuma K, Yanagida-Asanuma E, Kim K, Mundel P. Actin up: regulation of podocyte structure and function by components of the actin cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol 17: 428–437, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Faul C, Donnelly M, Merscher-Gomez S, Chang YH, Franz S, Delfgaauw J, Chang JM, Choi HY, Campbell KN, Kim K, Reiser J, Mundel P. The actin cytoskeleton of kidney podocytes is a direct target of the antiproteinuric effect of cyclosporine A. Nat Med 14: 931–938, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garg P, Rabelink T. Glomerular proteinuria: a complex interplay between unique players. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 18: 233–242, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garg P, Verma R, Cook L, Soofi A, Venkatareddy M, George B, Mizuno K, Gurniak C, Witke W, Holzman LB. Actin-depolymerizing factor cofilin-1 is necessary in maintaining mature podocyte architecture. J Biol Chem 285: 22676–22688, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnstone DB, Zhang J, George B, Leon C, Gachet C, Wong H, Parekh R, Holzman LB. Podocyte-specific deletion of Myh9 encoding nonmuscle myosin heavy chain 2A predisposes mice to glomerulopathy. Mol Cell Biol 31: 2162–2170, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones N, Blasutig IM, Eremina V, Ruston JM, Bladt F, Li H, Huang H, Larose L, Li SS, Takano T, Quaggin SE, Pawson T. Nck adaptor proteins link nephrin to the actin cytoskeleton of kidney podocytes. Nature 440: 818–823, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaplan JM, Kim SH, North KN, Rennke H, Correia LA, Tong HQ, Mathis BJ, Rodriguez-Perez JC, Allen PG, Beggs AH, Pollak MR. Mutations in ACTN4, encoding alpha-actinin-4, cause familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet 24: 251–256, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krendel M, Kim SV, Willinger T, Wang T, Kashgarian M, Flavell RA, Mooseker MS. Disruption of Myosin 1e promotes podocyte injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 86–94, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mele C, Iatropoulos P, Donadelli R, Calabria A, Maranta R, Cassis P, Buelli S, Tomasoni S, Piras R, Krendel M, Bettoni S, Morigi M, Delledonne M, Pecoraro C, Abbate I, Capobianchi MR, Hildebrandt F, Otto E, Schaefer F, Macciardi F, Ozaltin F, Emre S, Ibsirlioglu T, Benigni A, Remuzzi G, Noris M. MYO1E mutations and childhood familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med 365: 295–306, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moeller MJ, Sanden SK, Soofi A, Wiggins RC, Holzman LB. Podocyte-specific expression of cre recombinase in transgenic mice. Genesis 35: 39–42, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanna-Cherchi S, Burgess KE, Nees SN, Caridi G, Weng PL, Dagnino M, Bodria M, Carrea A, Allegretta MA, Kim HR, Perry BJ, Gigante M, Clark LN, Kisselev S, Cusi D, Gesualdo L, Allegri L, Scolari F, D'Agati V, Shapiro LS, Pecoraro C, Palomero T, Ghiggeri GM, Gharavi AG. Exome sequencing identified MYO1E and NEIL1 as candidate genes for human autosomal recessive steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int 80: 389–396, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schlondorff D, Banas B. The mesangial cell revisited: no cell is an island. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1179–1187, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sekine T, Konno M, Sasaki S, Moritani S, Miura T, Wong WS, Nishio H, Nishiguchi T, Ohuchi MY, Tsuchiya S, Matsuyama T, Kanegane H, Ida K, Miura K, Harita Y, Hattori M, Horita S, Igarashi T, Saito H, Kunishima S. Patients with Epstein-Fechtner syndromes owing to MYH9 R702 mutations develop progressive proteinuric renal disease. Kidney Int 78: 207–214, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seri M, Cusano R, Gangarossa S, Caridi G, Bordo D, Lo Nigro C, Ghiggeri GM, Ravazzolo R, Savino M, Del Vecchio M, d'Apolito M, Iolascon A, Zelante LL, Savoia A, Balduini CL, Noris P, Magrini U, Belletti S, Heath KE, Babcock M, Glucksman MJ, Aliprandis E, Bizzaro N, Desnick RJ, Martignetti JA. Mutations in MYH9 result in the May-Hegglin anomaly, and Fechtner and Sebastian syndromes. The May-Heggllin/Fechtner Syndrome Consortium. Nat Genet 26: 103–105, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shih NY, Li J, Cotran R, Mundel P, Miner JH, Shaw AS. CD2AP localizes to the slit diaphragm and binds to nephrin via a novel C-terminal domain. Am J Pathol 159: 2303–2308, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Skowron JF, Bement WM, Mooseker MS. Human brush border myosin-I and myosin-Ic expression in human intestine and Caco-2BBe cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 41: 308–324, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tryggvason K, Patrakka J, Wartiovaara J. Hereditary proteinuria syndromes and mechanisms of proteinuria. N Engl J Med 354: 1387–1401, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Verma R, Kovari I, Soofi A, Nihalani D, Patrie K, Holzman LB. Nephrin ectodomain engagement results in Src kinase activation, nephrin phosphorylation, Nck recruitment, and actin polymerization. J Clin Invest 116: 1346–1359, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Welsh GI, Saleem MA. The podocyte cytoskeleton–key to a functioning glomerulus in health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 14–21, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yaddanapudi S, Altintas MM, Kistler AD, Fernandez I, Moller CC, Wei C, Peev V, Flesche JB, Forst AL, Li J, Patrakka J, Xiao Z, Grahammer F, Schiffer M, Lohmuller T, Reinheckel T, Gu C, Huber TB, Ju W, Bitzer M, Rastaldi MP, Ruiz P, Tryggvason K, Shaw AS, Faul C, Sever S, Reiser J. CD2AP in mouse and human podocytes controls a proteolytic program that regulates cytoskeletal structure and cellular survival. J Clin Invest 121: 3965–3980, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]